Rubinsztein, Bento, and Deretic discuss the beneficial roles of autophagy in the context of infectious and neurodegenerative diseases.

Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved process that uses double-membrane vesicles to deliver cytoplasmic contents to lysosomes for degradation. Although autophagy may impact many facets of human biology and disease, in this review we focus on the ability of autophagy to protect against certain neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. Autophagy enhances the clearance of toxic, cytoplasmic, aggregate-prone proteins and infectious agents. The beneficial roles of autophagy can now be extended to supporting cell survival and regulating inflammation. Autophagic control of inflammation is one area where autophagy may have similar benefits for both infectious and neurodegenerative diseases beyond direct removal of the pathogenic agents. Preclinical data supporting the potential therapeutic utility of autophagy modulation in such conditions is accumulating.

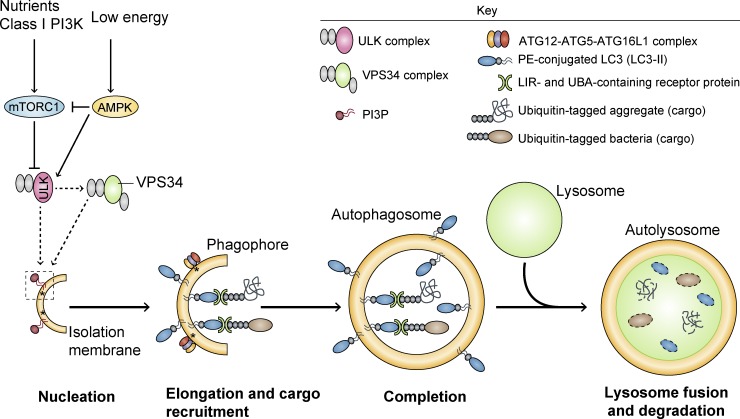

Macroautophagy is one of the major routes for the degradation of intracytoplasmic contents, including proteins and organelles such as mitochondria. The earliest morphologically recognizable intermediates in this pathway are phagophores, which evolve into double-membraned, sac-shaped structures. After the edges of the phagophores extend and fuse, engulfing a portion of cytoplasm, they become known as autophagosomes. These are then trafficked along microtubules in a direction that is biased toward the perinuclear microtubule-organizing center, where the lysosomes are clustered. This brings the autophagosomes close to lysosomes, enabling fusion of these different organelles, after which the lysosomal hydrolases degrade the autophagic contents (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of autophagy. Activation of AMPK and/or inhibition of mTORC1 by various stress signals induces activation of the ATG1–ULK1 complex, which positively regulates the activity of the VPS34 complex via phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms. Class III PI3K VPS34 provides PI3P to the phagophore, which seems to define the LC3-lipidation sites by assisting in the recruitment of the ATG12–ATG5–ATG16L1 complex to the membrane (asterisks). After the binding of ATG12–ATG5–ATG16L1 complex to the phagophore and LC3 conjugation to PE (LC3-II), the membrane elongates and engulfs portions of the cytoplasm, ultimately leading to the formation of the complete autophagosome. Proteins such as p62, NDP52, and NBR1 confer substrate selectivity to the pathway by establishing a bridge between LC3-II and specific ubiquitinated cargo (e.g., aggregates, microbes, mitochondria, and peroxisomes), through their LIR and UBA domains, respectively. In the final step of the process, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, resulting in the degradation of the vesicle contents. AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; ULK, Unc-51-like kinase; VPS34, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase VPS34; PI3P, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; LIR, LC3-interacting region; UBA, ubiquitin associated domain.

There are two additional forms of autophagy that will not be considered in detail in this review. Microautophagy involves the direct sequestration of portions of the cytoplasm by lysosomes, and has been mainly studied in yeast. Chaperone-mediated autophagy captures proteins that contain a pentapeptide motif related to KFERQ via Hsc70, which targets proteins to LAMP2A. LAMP2A then serves as a translocation channel to enable import of such substrates into the lysosomes. This pathway is perturbed by proteins causing certain neurodegenerative diseases and has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Cuervo and Wong, 2014).

Much of the pioneering work in the macroautophagy (henceforth referred to as autophagy in this review) field was initiated in yeast, where autophagy protects against cellular starvation. Although this role is conserved across evolution, more recent studies in mammalian systems have highlighted the importance of autophagy in diverse areas of physiology and disease. In this review, we will focus on the protective roles of autophagy in neurodegenerative and infectious diseases (Fig. 2). We will start by outlining the basic models where autophagosomes engulf and degrade neurodegeneration-associated aggregate-prone proteins or infectious agents. We will then describe possible mechanisms for enhancing the capture of such substrates to extents greater than would occur with bulk autophagy, during which one assumes there is random sequestration of cytoplasmic contents. We will extend the discussion of the roles of autophagy in these diseases by considering more complex consequences, including control of cell death, immunity, and inflammation. Although there are aspects that have been explored more in neurodegenerative diseases than infectious diseases, and vice versa, we believe that the opportunity to consider both in parallel will enable consideration of new hypotheses and cross-fertilization. We propose that the two main areas of overlap between the roles of autophagy in neurodegeneration and infectious disease are: (a) similarities in the shared usage of autophagic receptors in defending against pathology-inducing agents in both classes of disease (Birgisdottir et al., 2013), and (b) the now well-documented antiinflammatory action of autophagy (Deretic et al., 2013, 2015). This juxtaposition of autophagic roles in apparently distinct classes of diseases is a testament to the relevance of autophagy in cleansing the cellular interiors no matter what the disease context is, and is particularly timely in view of the explosion of data in the two fields. Finally, we will consider possible autophagy-related therapeutic strategies that may be of significance for these diseases, including the possibility of developing agents that may target both sets of conditions.

Figure 2.

Protective roles of autophagy in neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. A major role for autophagy in neurodegenerative and infectious diseases involves the clearance of toxic aggregate-prone proteins and infectious agents, respectively. However, it also exerts ancillary beneficial roles by controlling cell death and exacerbated inflammatory responses associated with these pathologies.

Autophagy biology

The membranes that contribute to phagophore formation and elongation may derive from multiple sources, including the ER (including ER exit sites and ER–mitochondrial contact sites; Hayashi-Nishino et al., 2009; Hamasaki et al., 2013), the ER–Golgi intermediate compartment (Ge et al., 2013, 2014), recycling endosomes (Longatti et al., 2012; Puri et al., 2013), plasma membrane (Ravikumar et al., 2010; Moreau et al., 2011), the Golgi complex (Young et al., 2006; Ohashi and Munro, 2010), and, potentially, lipid droplets (Dupont et al., 2014; Shpilka et al., 2015). The coordination of the membrane rearrangements that enable autophagosome formation, and their subsequent delivery to the lysosomes, is regulated by multiple autophagy-related (ATG) proteins. Some of these participate in two ubiquitin-like conjugation reactions. The first involves ATG12 conjugation to ATG5. This ATG12–ATG5 conjugate binds noncovalently with ATG16L1 to form a complex essential for phagophore expansion (Rubinsztein et al., 2012a). These complexes are localized to the phagophore and dissociate after the autophagosome is formed. The completion of autophagosome formation is assisted by a second conjugation reaction involving ATG8/LC3. LC3 is first cleaved by ATG4 to form cytosolic LC3-I, which is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine on autophagosome precursors to form membrane-associated LC3-II.

Autophagy signaling

A primordial signaling pathway regulating autophagy, which is conserved from yeast to humans, is mediated by the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which inhibits autophagy by phosphorylating proteins such as ATG1 and ATG13 that act upstream in phagophore formation (Hosokawa et al., 2009; Jung et al., 2009). However, several mTORC1-independent pathways have been described, including low inositol triphosphate levels (Sarkar et al., 2005), which activate autophagy by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Low inositol triphosphate levels reduce calcium flow from the ER to mitochondria, and the lower intramitochondrial calcium levels inhibit oxidative phosphorylation, thereby decreasing ATP levels, which activates AMPK (Cárdenas et al., 2010). Some signals activate autophagy by stimulating III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (called VPS34), which produces phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P); this, in turn, helps to recruit ATG16L1 to sites of autophagosome formation (Dooley et al., 2014). Some of these signals act via the ATG6 orthologue Beclin 1, which stimulates VPS34 activity (Furuya et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2013). However, PI3P-independent forms of autophagy have also been described, and some of these appear to be mediated via the use of PI5P as an alternative to PI3P (Vicinanza et al., 2015). Interestingly, many of the stimuli that induce autophagy are stress responses. For example, mTORC1 activity is inhibited by amino acid starvation (Chen et al., 2014), the levels of PI5P are induced by glucose starvation (Vicinanza et al., 2015), and AMPK (a key sensor of ATP levels in the cells) is enhanced when ATP energy stores are reduced (Hardie et al., 2012). These pathways are also directly linked to antiinfective or general immune signaling players, such as IRGM (an antituberculosis and Crohn’s disease factor that interacts with ULK1 and Beclin 1, promoting their coassembly; Chauhan et al., 2015), TAK1 and NOD2/RIPK2 (which activate AMPK and ULK1, respectively), and NLRP (which interacts with Beclin 1). The pathways also receive input from TLRs, IL-1β, and other immune system regulators (Deretic et al., 2013).

In the context of neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease (HD), there appears to be a decrease in mTORC1 activity in neurons with large aggregates (Ravikumar et al., 2004). However, the ultimate consequences for autophagy may not be straightforward, as excitotoxicity will increase calcium levels, which in turn inhibits autophagosome biogenesis (Williams et al., 2008), whereas mutant huntingtin binds the autophagy inducer Rhes to impair autophagy (Mealer et al., 2014). Thus, the eventual consequences of a specific mutation or disease situation are frequently unpredictable, as multiple activating and inhibitory pathways may be affected. Furthermore, non–cell-autonomous effects may have an impact. For example, the increased nitric oxide released by glial cells in diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease impairs autophagosome biogenesis (Sarkar et al., 2011).

How autophagy clears aggregate-prone intracytoplasmic proteins

Intracellular protein misfolding and aggregation are features of many late-onset neurodegenerative diseases, which are referred to as proteinopathies. These include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, tauopathies, and polyglutamine expansion diseases (including HD and various spinocerebellar ataxias [SCAs]). Currently, there are no effective therapeutic strategies that slow or prevent the neurodegeneration resulting from these diseases in humans. The mutations that cause HD and many other proteinopathies (e.g., polyglutamine diseases and tauopathies) confer novel toxic functions on the specific protein, and disease severity frequently correlates with expression levels. Thus, it is important to understand the factors regulating the expression levels of these aggregate-prone proteins. When these proteins are intracytoplasmic, they can be removed either via the ubiquitin-proteasome system or via autophagy. Whereas the former route is generally more rapid, it is restricted to species that can enter the narrow proteasome barrel, which precludes oligomers and higher order structures. These species can be cleared by autophagy. Consistent with the model above, the aggregate-prone forms of such proteins, including tau (Berger et al., 2006), α-synuclein (Webb et al., 2003; Spencer et al., 2009), mutant huntingtin (Ravikumar et al., 2002), and mutant ataxin 3 (Berger et al., 2006) appear to have a higher dependency on autophagy for their clearance compared with the wild-type forms.

Autophagy in infectious and inflammatory diseases

In the context of infectious and inflammatory diseases, autophagy plays at least three roles. Autophagy can clear intracellular microbes and moderate host innate immune responses to microbial products (through recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs]) and endogenous sources of inflammation (via recognition of damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs]; Deretic et al., 2013). In addition, autophagy may also protect by enhancing the removal of relevant toxins, such as Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin (Maurer et al., 2015).

The direct elimination of microbes by autophagy (a process termed xenophagy) receives the most attention, although it is likely that the antiinflammatory role of autophagy independent of, or during, infection plays an equally important host protective role (Deretic et al., 2015). The former perception is understandable, as intracellular microbes such as invading bacteria or viruses are large intracytoplasmic objects that represent potential (and in many cases actual) substrates for autophagic removal. Prototypical examples of this are Mycobacterium tuberculosis in infected macrophages (Gutierrez et al., 2004) and animal models (Castillo et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2012; Manzanillo et al., 2013) and the Group A Streptococcus that manages to invade host cells (Nakagawa et al., 2004), but many other bacteria (including Listeria, Salmonella, and Shigella) are at least partially susceptible to autophagic elimination when tested in cellular systems (Gomes and Dikic, 2014; Huang and Brumell, 2014). Similarly, viruses, including HIV (Kyei et al., 2009; Shoji-Kawata et al., 2013; Mandell et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2015; Sagnier et al., 2015), as well as protozoans (Choi et al., 2014), can be targeted by conventional or modified forms of autophagy. In many cases, an evolutionary balance exists whereby the host’s ability to deploy autophagy against the microbe is countered by bacterial or viral adaptations, and in most instances a successful intracellular pathogen has very specific antiautophagy strategies (Huang and Brumell, 2014). Such adaptations are seen in a wide range of pathogens, including Shigella and Legionella (Huang and Brumell, 2014), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Deretic et al., 2015), HSV-1 (Orvedahl et al., 2007; Lussignol et al., 2013), and HIV (Kyei et al., 2009; Borel et al., 2014). Interestingly, interactions between autophagy and viral products can lead to neurological manifestations; for example, HIV proteins have been associated with HIV-induced dementia and manifestations of neuroAIDS (Meulendyke et al., 2014; El-Hage et al., 2015; Fields et al., 2015). As with other host–pathogen interactions, a balance between a microbe and the host is established, leading to chronic disease or subclinical or latent infection, as in latent tuberculosis or persistent viral infections. This represents a therapeutic opportunity to tip the balance against the pathogen by enhancing autophagy using pharmacological intervention. However, in several cases, evidence of microbial exploitation of autophagy (not just defense against it, but in some cases enhancing survival or promoting spread) suggests that this approach must be carefully tailored. Some examples of the latter include Brucella (Starr et al., 2008), Anaplasma (formerly Ehrlichia; Niu et al., 2012), and poliovirus (Bird et al., 2014).

Autophagy receptor proteins

Whereas autophagy was originally considered to be a nonselective bulk degradation process, accumulating data now supports the concept of selective macroautophagy, where the cell uses receptor proteins to enhance the incorporation of specific cargoes into autophagosomes. These receptor proteins include p62 (Bjørkøy et al., 2005; Pankiv et al., 2007), optineurin (Wild et al., 2011), NDP52 (Thurston et al., 2009), NBR1 (Kirkin et al., 2009), ALFY (Filimonenko et al., 2010), TRIM5 (Mandell et al., 2014), and Tollip (Lu et al., 2014). The canonical model for this process involves these receptors binding to cargoes, typically via interaction with ubiquitinated motifs, and the receptor binding to the autophagosome membrane protein LC3 via LC3-interacting domains (Birgisdottir et al., 2013; Stolz et al., 2014). However, some classical receptors, like p62 and NBR1, may not require LC3-binding to be incorporated into autophagosomes (Itakura and Mizushima, 2011). Although systematic studies have not yet been performed, many of these receptors, including p62 and optineurin, appear to be able to assist autophagic capture of both neurodegenerative disease-causing proteins and infectious agents. In their antimicrobial role, these receptors are referred to as a new class of pattern recognition receptors termed sequestosome 1/p62-like receptors (Birgisdottir et al., 2013; Deretic et al., 2013, 2015). The ability of receptor proteins to recruit substrates to autophagosomes can also be modulated by posttranslational modifications. For example, the TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) phosphorylates optineurin on Ser177, enhancing LC3-binding affinity and autophagic clearance of substrates, such as expanded polyglutamines as seen with mutant huntingtin (Korac et al., 2013), and Salmonella (Wild et al., 2011). Likewise, TBK1- (Pilli et al., 2012) or casein kinase-mediated (Matsumoto et al., 2011) phosphorylation of p62 at residue S403 has additional benefits in enhancing recognition of ubiquitinated targets by the ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain of p62, as is observed in clearance of polyglutamine expansion targets (Matsumoto et al., 2011) or mycobacteria (Pilli et al., 2012). Enhancement of ubiquitin recognition by the p62 UBA is also under control of direct phosphorylation by ULK1, which phosphorylates Ser405 and Ser409 of murine p62 (equivalent to human Ser403 and Ser407; Lim et al., 2015). ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of the former residue additionally destabilizes the UBA dimer interface, thus increasing binding affinity of p62 to ubiquitin in response to proteotoxic stress (Lim et al., 2015). In the case of p62, and possibly other molecules, the activity of receptors can themselves be influenced by a disease protein. Huntingtin, the Huntington disease-causing protein, appears to act as a scaffold for selective macroautophagy but it is dispensable for bulk autophagy (Ochaba et al., 2014; Rui et al., 2015). Huntingtin interacts with p62 to enhance its interactions with LC3 and with ubiquitin-modified substrates (Rui et al., 2015). Interestingly, in some cases, such as with optineurin (Tumbarello et al., 2012) and TRIM5α (Mandell et al., 2014), the adaptor proteins themselves also can act as bulk autophagy regulators. It is interesting to note that several of these proteins, including p62, TBK1, and optineurin, are mutated in neurodegenerative diseases such as motor neuron disease and forms of frontotemporal dementia (Maruyama et al., 2010; Fecto et al., 2011; Freischmidt et al., 2015; Pottier et al., 2015). Of further note is the shared role of autophagy receptors in protection against neurodegeneration and infectious agents, a principle that may extend to new receptor categories (e.g., TRIMs or other classes), as their functions are further elucidated with future progress in selective autophagy.

Additional protective properties of autophagy in neurodegenerative and infectious diseases

A major consequence of autophagy in many of these diseases is promotion of the removal of toxic proteins or infectious agents, but there may be additional benefits. Autophagy is generally an antiapoptotic process that reduces caspase activation (Ravikumar et al., 2006; Hou et al., 2010; Amir et al., 2013; Meunier et al., 2014). In a manner similar to what has been observed in yeast, autophagy inhibition sensitizes mammalian cells to nutrient deprivation, whereas autophagy compromise results in apoptosis (Boya et al., 2005). Consistent with this, autophagy activation protects against proapoptotic insults in culture and in vivo. This may be relevant in neurodegenerative diseases, where subapoptotic caspase activities may enhance disease by processes including cleavage of proteins like mutant huntingtin (Wellington et al., 2002; Warby et al., 2008) or tau (Rohn et al., 2002) to increase their toxicities, or by trimming of dendritic spines (Pozueta et al., 2013; Ertürk et al., 2014).

Autophagy also regulates inflammation. As recently reviewed (Deretic et al., 2015), the antiinflammatory functions of autophagy in principle involve: (a) prevention of spurious inflammasome activation and down-regulation of the response once inflammasome is activated (Saitoh et al., 2008; Nakahira et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011; Lupfer et al., 2013) and (b) inhibition of type I IFN responses directly (Jounai et al., 2007; Saitoh et al., 2009; Konno et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014) or indirectly (Tal et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2014). The underlying processes include autophagic elimination of endogenous DAMPs (e.g., depolarized mitochondria leaking ROS, mitochondrial DNA, and oxidized mitochondrial DNA; Saitoh et al., 2008; Nakahira et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011; Lupfer et al., 2013), which lowers the threshold for inflammasome activation, or direct targeting and degradation of inflammasome components and products such as NLRP3, ASC, and IL-1β (Harris et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2012; Chuang et al., 2013); this, in turn, tapers the intensity and duration of inflammasome activation. However, the engagement of autophagy with cellular outputs of IL-1β, a prototypical unconventionally secreted protein, is more complex (Dupont et al., 2011; Ponpuak et al., 2015). Autophagy assists secretion of IL-1β (Dupont et al., 2011; Öhman et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014), a cytosolic protein that lacks a signal peptide and is unable to enter the conventional secretory pathway via the ER and Golgi. Thus, autophagy also plays a positive role in delivering IL-1β and possibly other proinflammatory substrates, once they are properly activated in the cytosol, to the extracellular space where they perform their signaling functions (Ponpuak et al., 2015).

The autophagic interference with type I IFN responses occurs either directly by targeting signaling molecules within the pathway, starting with RIG-I-like receptors or cGAMP synthase (sensors recognizing cytosolic nucleic acids) and converging upon stimulator of the interferon gene (STING) and interferon regulatory factors (Jounai et al., 2007; Saitoh et al., 2009; Konno et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014), or indirectly by removing agonist sources that activate these pathways (Tal et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2014). The p62 receptor also appears to have a role in restraining TCR activation of NF-κB signaling mediated by Bcl10. Although p62 enables the signaling to occur in the first place, it also serves as a receptor to degrade Bcl10, which becomes ubiquitinated as a response to TCR activation. Thus, this mechanism may serve to protect cells from NF-κB hyperactivation in response to TCR signaling (Paul et al., 2012). The antiinflammatory action of autophagy applies to both infectious and inflammatory diseases (either sterile or associated with microbial triggers), such as Crohn’s disease. These relationships may extend to neuroinflammation in acute and chronic neurological disorders. Many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with inflammatory responses in glia, which may contribute to pathology (Czirr and Wyss-Coray, 2012), and it is possible that autophagy in glial cells may play a role in keeping these processes in check, although this domain has not been carefully explored.

Autophagy also plays key roles in protecting cells against infectious agents that either remain within vacuoles or escape from phagosomes into the cytoplasm (Huang and Brumell, 2014). Examples of intracellular bacterial pathogens in most cases represent a mixed spectrum of retention within the parasitophorous vacuole, partial permeabilization of such vacuoles, or full escape of bacteria into the cytosol. Such mixed events are often skewed to one or the other end of the spectrum, with Shigella (Ogawa et al., 2005; Dupont et al., 2009; Mostowy et al., 2011; Ogawa et al., 2011; Thurston et al., 2012) and Listeria (Py et al., 2007; Mostowy et al., 2011) predominantly escaping into the cytosol, whereas Salmonella (Zheng et al., 2009; Wild et al., 2011; Huett et al., 2012; Thurston et al., 2012; Gomes and Dikic, 2014) and M. tuberculosis (Gutierrez et al., 2004; Watson et al., 2012; Manzanillo et al., 2013; Deretic et al., 2015) primarily reside in undamaged vacuoles although recent studies indicate that it penetrates into the cytosol. Parallels may exist in neurodegenerative diseases, where autophagy may help glial cell clearance of extracellular β-amyloid if the internalized peptide is found to gain access to the cytosol (Li et al., 2013). This principle may be also relevant to diseases like Parkinson’s disease and forms of frontotemporal dementia, where there is increasing evidence for extracellular spread of the relevant toxic proteins like α-synuclein and tau via prion-like mechanisms (Desplats et al., 2009; Frost et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Steiner et al., 2011). However, impaired clearance of autophagosomes due to defective lysosomal function may cause excess secretion of such proteins and exacerbate extracellular spread (Ejlerskov et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2013).

Therapeutic and clinical implications

Up-regulation of autophagy via mTORC1-dependent and -independent routes has been shown to enhance the clearance of neurodegenerative disease-causing proteins and reduce their toxicity in a wide range of cells in Drosophila, zebrafish, and mouse models (Ravikumar et al., 2004; Furuya et al., 2005; Sarkar et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007; Pickford et al., 2008; Menzies et al., 2010; Spilman et al., 2010; Cortes et al., 2012; Schaeffer et al., 2012; Hebron et al., 2013; Frake et al., 2015). This strategy has shown promise in a range of disease models, including tauopathies, α-synucleinopathies, HD, spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, and familial prion disease. The drugs used in these diseases include a rapamycin analogue and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers like rilmenidine and trehalose (Frake et al., 2015; this work also considers the points of action of many of these drugs). Conversely, autophagy inhibition enhances the toxicity of these proteins and, in parallel, leads to the accumulation of the relevant protein (Frake et al., 2015).

Similarly, autophagy up-regulation may enhance the clearance of a range of infectious agents, with some of the more developed aspects being shown with M. tuberculosis, including multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. In some cases, the support for this type of strategy has been strengthened by mouse models and preclinical data. For example, drugs used for psychiatric and neurological disorders such as the antidepressants fluoxetine (Stanley et al., 2014) and nortriptyline (Sundaramurthy et al., 2013), and the antiepileptic carbamazepine (Rubinsztein et al., 2012b; Schiebler et al., 2015), have been shown to counter M. tuberculosis infection, possibly through autophagy. Notably, carbamazepine, an inducer of autophagy, has been shown to act on MDR M. tuberculosis in vivo (Schiebler et al., 2015). Furthermore, several tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also act as inducers of autophagy, have been tested in vitro and in mouse models for their potential in host-directed therapy (HDT) in tuberculosis. This includes gefitinib, an inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) shown to activate autophagy and suppress M. tuberculosis in macrophages and, to some extent, in infected mice (Stanley et al., 2014). It also includes imatinib (Gleevec), a known inducer of autophagy (Ertmer et al., 2007) and inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase Abl, whose depletion has been shown to suppress intracellular M. tuberculosis (Jayaswal et al., 2010), with imatinib reducing M. tuberculosis bacillary loads in infected macrophages (Bruns et al., 2012) and in a mouse model of tuberculosis (Napier et al., 2011). Other antituberculosis HDT autophagy-inducing candidate drugs include antiparasitic pharmaceuticals such as nitozoxanide (Lam et al., 2012) and cholesterol-lowering drugs, i.e., statins (Parihar et al., 2014).

There may be a wide range of strategies that could be used in human conditions, including drugs (where several FDA-approved drugs show promise in preclinical models), peptides (Shoji-Kawata et al., 2013), and possibly topical agents for certain infectious agents. Furthermore, there may be opportunities for modulating selective autophagy via adaptor proteins. Strategies could include regulating posttranslational modifications of proteins that could enhance their activities.

Neurodegenerative disease-causing proteins and various infectious agents can also impair autophagy. Although this issue has been dealt with in detail elsewhere (Menzies et al., 2015), one recent example includes the VPS35 D620N Parkinson’s disease mutation that impacts early stages of autophagosome biogenesis (Zavodszky et al., 2014). PICALM, an Alzheimer’s disease GWAS hit, impacts both autophagosome formation and autophagosome degradation, and altered PICALM activity in culture and in vivo leads to the accumulation and increased toxicity of tau, a protein which is an important driver of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis (Moreau et al., 2014). Likewise, infectious agents like Salmonella (Mesquita et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2014), Legionella (Choy et al., 2012), Shigella (Ogawa et al., 2005), Listeria (Birmingham et al., 2008; Yoshikawa et al., 2009), and viruses (Orvedahl et al., 2007; Kyei et al., 2009; Lussignol et al., 2013; Borel et al., 2014) have multiple mechanisms that can at least partially counter or fully impair autophagy. In extreme cases, some infectious agents can convert autophagosomes into a replicative (Niu et al., 2012) or persistence (Birmingham et al., 2008) niche.

Understanding the biology of the relevant disease and the proposed treatment modality will enhance the probability of successful therapies. In diseases where there is impaired autophagosome degradation, including the lysosomal storage diseases, there may be concerns about the risks versus the benefits of increasing autophagosome biogenesis. However, this may depend on the extent of the block of autophagosome degradation, as stimulation of autophagosome biogenesis appeared to enhance autophagic substrate clearance in cell culture models of Niemann-Pick Type C1 (Sarkar et al., 2013), a lysosomal storage disease associated with delayed autophagosome degradation.

Likewise, it is important to understand the actions and possible side effects of drugs used for these diseases. For example, azithromycin, a potent antibiotic, is used as a prophylactic against mycobacterial infections in cystic fibrosis patients. However, mycobacteria that develop resistance against azithromycin accumulate in culture and in vivo when treated with this agent, as azithromycin also impairs autophagosome degradation (Renna et al., 2011). Thus, the advantages of this drug as an antimicrobial for sensitive species may be, in part, counterbalanced by the risks of autophagy inhibition for resistant mycobacterial species. This possibility is suggested by preliminary clinical data which have reported increased risks of resistant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in cystic fibrosis patients treated chronically with azithromycin.

Future directions

Extensive preclinical animal model data support the promise of the therapeutic use of autophagy up-regulation in various neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. This aim may be achievable with existing approved drugs using repurposing strategies. Here, a major challenge will be making the transition between mice and humans, where one needs to contend with very different pharmacokinetics for drugs between the species. However, in these scenarios, the task is simplified by the existing human safety and pharmacokinetics data on the drugs. It is likely that most, if not all, of the approved drugs that influence autophagy have effects on other pathways, and although these may not be limiting or even disadvantageous, there would be major advantages both for experimental studies and possibly human treatments to identify more specific autophagy modulators. These may be more elusive than previously anticipated, given the increasing awareness of autophagy-independent roles of many ATG proteins.

A second major hurdle with such drug discovery efforts is disease modeling. It is currently impossible to model sporadic Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease in rodents. These limitations may be partially mitigated if suitable iPS stem cell–derived neuronal models are generated for sporadic cases. These difficulties may be less of an issue for monogenic diseases that can be more faithfully recapitulated in mice. However, even in these cases, the disease course is often much more rapid in the models, which may have consequences for the way one interprets the preclinical data.

Future work will establish the potential for harnessing autophagy as a therapeutic option in various neurodegenerative and infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust (095317/Z/11/Z Principal Research Fellowship to D.C. Rubinsztein and strategic award 100140), the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Unit in Dementia at Addenbrooke’s Hospital (D.C. Rubinsztein), and the National Institutes of Health (AI042999 and AI111935; V. Deretic) for funding our work.

D.C. Rubinsztein has received grant funding from MedImmune and is a scientific advisor for E3Bio and Bioblast. The authors declare no additional competing financial interests.

Note added in proof. While this manuscript was in production, further evidence of the extensive overlaps between inflammatory response systems and autophagy was documented in the context of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-dependent type I IFN production and autophagic clearance of M. tuberculosis. (Collins, A.C., H. Cai, T. Li, L.H. Franco, X.D. Li, V.R. Nair, C.R. Scharn, C.E. Stamm, B. Levine, Z.J. Chen, and M.U. Shiloh. 2015. Cell host Microbe. 17:820-828; Watson, R.O., S.L. Bell, D.A. MacDuff, J.M. Kimmey, E.J. Diner, J. Olivas, R.E. Vance, C.L. Stallings, H.W. Virgin, and J.S. Cox. 2015. Cell host Microbe. 17:811-819).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATG

- autophagy-related

- DAMP

- damage-associated molecular pattern

- HD

- Huntington’s disease

- mTORC1

- mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- PAMP

- pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- SCA

- spinocerebellar ataxia

- TBK1

- TANK-binding kinase 1

- UBA

- ubiquitin-associated

References

- Amir M., Zhao E., Fontana L., Rosenberg H., Tanaka K., Gao G., and Czaja M.J.. 2013. Inhibition of hepatocyte autophagy increases tumor necrosis factor-dependent liver injury by promoting caspase-8 activation. Cell Death Differ. 20:878–887. 10.1038/cdd.2013.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Z., Ravikumar B., Menzies F.M., Oroz L.G., Underwood B.R., Pangalos M.N., Schmitt I., Wullner U., Evert B.O., O’Kane C.J., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2006. Rapamycin alleviates toxicity of different aggregate-prone proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15:433–442. 10.1093/hmg/ddi458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S.W., Maynard N.D., Covert M.W., and Kirkegaard K.. 2014. Nonlytic viral spread enhanced by autophagy components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:13081–13086. 10.1073/pnas.1401437111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgisdottir Å.B., Lamark T., and Johansen T.. 2013. The LIR motif - crucial for selective autophagy. J. Cell Sci. 126:3237–3247. 10.1242/jcs.126128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham C.L., Canadien V., Kaniuk N.A., Steinberg B.E., Higgins D.E., and Brumell J.H.. 2008. Listeriolysin O allows Listeria monocytogenes replication in macrophage vacuoles. Nature. 451:350–354. 10.1038/nature06479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørkøy G., Lamark T., Brech A., Outzen H., Perander M., Overvatn A., Stenmark H., and Johansen T.. 2005. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J. Cell Biol. 171:603–614. 10.1083/jcb.200507002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel S., Robert-Hebmann V., Alfaisal J., Jain A., Faure M., Espert L., Chaloin L., Paillart J.C., Johansen T., and Biard-Piechaczyk M.. 2014. HIV-1 viral infectivity factor interacts with microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 and inhibits autophagy. AIDS. 29:275–286. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P., González-Polo R.A., Casares N., Perfettini J.L., Dessen P., Larochette N., Métivier D., Meley D., Souquere S., Yoshimori T., et al. 2005. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1025–1040. 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns H., Stegelmann F., Fabri M., Döhner K., van Zandbergen G., Wagner M., Skinner M., Modlin R.L., and Stenger S.. 2012. Abelson tyrosine kinase controls phagosomal acidification required for killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 189:4069–4078. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G.R., Bruckman R.S., Chu Y.L., and Spector S.A.. 2015. Autophagy induction by histone deacetylase inhibitors inhibits HIV type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 290:5028–5040. 10.1074/jbc.M114.605428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas C., Miller R.A., Smith I., Bui T., Molgó J., Müller M., Vais H., Cheung K.H., Yang J., Parker I., et al. 2010. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 142:270–283. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo E.F., Dekonenko A., Arko-Mensah J., Mandell M.A., Dupont N., Jiang S., Delgado-Vargas M., Timmins G.S., Bhattacharya D., Yang H., et al. 2012. Autophagy protects against active tuberculosis by suppressing bacterial burden and inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:E3168–E3176. 10.1073/pnas.1210500109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan S., Mandell M.A., and Deretic V.. 2015. IRGM Governs the Core Autophagy Machinery to Conduct Antimicrobial Defense. Mol. Cell. 58:507–521. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Zou Y., Mao D., Sun D., Gao G., Shi J., Liu X., Zhu C., Yang M., Ye W., et al. 2014. The general amino acid control pathway regulates mTOR and autophagy during serum/glutamine starvation. J. Cell Biol. 206:173–182. 10.1083/jcb.201403009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Park S., Biering S.B., Selleck E., Liu C.Y., Zhang X., Fujita N., Saitoh T., Akira S., Yoshimori T., et al. 2014. The parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Toxoplasma gondii is targeted for disruption by ubiquitin-like conjugation systems of autophagy. Immunity. 40:924–935. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy A., Dancourt J., Mugo B., O’Connor T.J., Isberg R.R., Melia T.J., and Roy C.R.. 2012. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science. 338:1072–1076. 10.1126/science.1227026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S.Y., Yang C.H., Chou C.C., Chiang Y.P., Chuang T.H., and Hsu L.C.. 2013. TLR-induced PAI-2 expression suppresses IL-1β processing via increasing autophagy and NLRP3 degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:16079–16084. 10.1073/pnas.1306556110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C.J., Qin K., Cook J., Solanki A., and Mastrianni J.A.. 2012. Rapamycin delays disease onset and prevents PrP plaque deposition in a mouse model of Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease. J. Neurosci. 32:12396–12405. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6189-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo A.M., and Wong E.. 2014. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in disease and aging. Cell Res. 24:92–104. 10.1038/cr.2013.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirr E., and Wyss-Coray T.. 2012. The immunology of neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 122:1156–1163. 10.1172/JCI58656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V., Saitoh T., and Akira S.. 2013. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13:722–737. 10.1038/nri3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V., Kimura T., Timmins G., Moseley P., Chauhan S., and Mandell M.. 2015. Immunologic manifestations of autophagy. J. Clin. Invest. 125:75–84. 10.1172/JCI73945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P., Lee H.J., Bae E.J., Patrick C., Rockenstein E., Crews L., Spencer B., Masliah E., and Lee S.J.. 2009. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:13010–13015. 10.1073/pnas.0903691106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley H.C., Razi M., Polson H.E., Girardin S.E., Wilson M.I., and Tooze S.A.. 2014. WIPI2 links LC3 conjugation with PI3P, autophagosome formation, and pathogen clearance by recruiting Atg12-5-16L1. Mol. Cell. 55:238–252. 10.1016/molcel.2014.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont N., Lacas-Gervais S., Bertout J., Paz I., Freche B., Van Nhieu G.T., van der Goot F.G., Sansonetti P.J., and Lafont F.. 2009. Shigella phagocytic vacuolar membrane remnants participate in the cellular response to pathogen invasion and are regulated by autophagy. Cell Host Microbe. 6:137–149. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont N., Jiang S., Pilli M., Ornatowski W., Bhattacharya D., and Deretic V.. 2011. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 30:4701–4711. 10.1038/emboj.2011.398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont N., Chauhan S., Arko-Mensah J., Castillo E.F., Masedunskas A., Weigert R., Robenek H., Proikas-Cezanne T., and Deretic V.. 2014. Neutral lipid stores and lipase PNPLA5 contribute to autophagosome biogenesis. Curr. Biol. 24:609–620. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejlerskov P., Rasmussen I., Nielsen T.T., Bergström A.L., Tohyama Y., Jensen P.H., and Vilhardt F.. 2013. Tubulin polymerization-promoting protein (TPPP/p25α) promotes unconventional secretion of α-synuclein through exophagy by impairing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 288:17313–17335. 10.1074/jbc.M112.401174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N., Rodriguez M., Dever S.M., Masvekar R.R., Gewirtz D.A., and Shacka J.J.. 2015. HIV-1 and morphine regulation of autophagy in microglia: limited interactions in the context of HIV-1 infection and opioid abuse. J. Virol. 89:1024–1035. 10.1128/JVI.02022-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer A., Huber V., Gilch S., Yoshimori T., Erfle V., Duyster J., Elsässer H.P., and Schätzl H.M.. 2007. The anticancer drug imatinib induces cellular autophagy. Leukemia. 21:936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk A., Wang Y., and Sheng M.. 2014. Local pruning of dendrites and spines by caspase-3-dependent and proteasome-limited mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 34:1672–1688. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3121-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecto F., Yan J., Vemula S.P., Liu E., Yang Y., Chen W., Zheng J.G., Shi Y., Siddique N., Arrat H., et al. 2011. SQSTM1 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 68:1440–1446. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields J., Dumaop W., Elueteri S., Campos S., Serger E., Trejo M., Kosberg K., Adame A., Spencer B., Rockenstein E., et al. 2015. HIV-1 Tat alters neuronal autophagy by modulating autophagosome fusion to the lysosome: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J. Neurosci. 35:1921–1938. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filimonenko M., Isakson P., Finley K.D., Anderson M., Jeong H., Melia T.J., Bartlett B.J., Myers K.M., Birkeland H.C., Lamark T., et al. 2010. The selective macroautophagic degradation of aggregated proteins requires the PI3P-binding protein Alfy. Mol. Cell. 38:265–279. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frake R.A., Ricketts T., Menzies F.M., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2015. Autophagy and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 125:65–74. 10.1172/JCI73944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freischmidt A., Wieland T., Richter B., Ruf W., Schaeffer V., Müller K., Marroquin N., Nordin F., Hübers A., Weydt P., et al. 2015. Haploinsufficiency of TBK1 causes familial ALS and fronto-temporal dementia. Nat. Neurosci. 18:631–636. 10.1038/nn.4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost B., Jacks R.L., and Diamond M.I.. 2009. Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J. Biol. Chem. 284:12845–12852. 10.1074/jbc.M808759200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya N., Yu J., Byfield M., Pattingre S., and Levine B.. 2005. The evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin 1 is required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor suppressor function. Autophagy. 1:46–52. 10.4161/auto.1.1.1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L., Melville D., Zhang M., and Schekman R.. 2013. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment is a key membrane source for the LC3 lipidation step of autophagosome biogenesis. eLife. 2:e00947 10.7554/eLife.00947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L., Zhang M., and Schekman R.. 2014. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and COPII generate LC3 lipidation vesicles from the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment. eLife. 3:e04135 10.7554/eLife.04135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes L.C., and Dikic I.. 2014. Autophagy in antimicrobial immunity. Mol. Cell. 54:224–233. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M.G., Master S.S., Singh S.B., Taylor G.A., Colombo M.I., and Deretic V.. 2004. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 119:753–766. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamasaki M., Furuta N., Matsuda A., Nezu A., Yamamoto A., Fujita N., Oomori H., Noda T., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y., et al. 2013. Autophagosomes form at ER-mitochondria contact sites. Nature. 495:389–393. 10.1038/nature11910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie D.G., Ross F.A., and Hawley S.A.. 2012. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:251–262. 10.1038/nrm3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J., Hartman M., Roche C., Zeng S.G., O’Shea A., Sharp F.A., Lambe E.M., Creagh E.M., Golenbock D.T., Tschopp J., et al. 2011. Autophagy controls IL-1beta secretion by targeting pro-IL-1beta for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:9587–9597. 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Nishino M., Fujita N., Noda T., Yamaguchi A., Yoshimori T., and Yamamoto A.. 2009. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1433–1437. 10.1038/ncb1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebron M.L., Lonskaya I., and Moussa C.E.. 2013. Nilotinib reverses loss of dopamine neurons and improves motor behavior via autophagic degradation of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22:3315–3328. 10.1093/hmg/ddt192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N., Hara T., Kaizuka T., Kishi C., Takamura A., Miura Y., Iemura S., Natsume T., Takehana K., Yamada N., et al. 2009. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:1981–1991. 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W., Han J., Lu C., Goldstein L.A., and Rabinowich H.. 2010. Autophagic degradation of active caspase-8: a crosstalk mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 6:891–900. 10.4161/auto.6.7.13038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., and Brumell J.H.. 2014. Bacteria-autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12:101–114. 10.1038/nrmicro3160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huett A., Heath R.J., Begun J., Sassi S.O., Baxt L.A., Vyas J.M., Goldberg M.B., and Xavier R.J.. 2012. The LRR and RING domain protein LRSAM1 is an E3 ligase crucial for ubiquitin-dependent autophagy of intracellular Salmonella Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe. 12:778–790. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E., and Mizushima N.. 2011p62 Targeting to the autophagosome formation site requires self-oligomerization but not LC3 binding. J. Cell Biol. 192:17–27. 10.1083/jcb.201009067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaswal S., Kamal M.A., Dua R., Gupta S., Majumdar T., Das G., Kumar D., and Rao K.V.. 2010. Identification of host-dependent survival factors for intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis through an siRNA screen. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000839 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jounai N., Takeshita F., Kobiyama K., Sawano A., Miyawaki A., Xin K.Q., Ishii K.J., Kawai T., Akira S., Suzuki K., and Okuda K.. 2007. The Atg5 Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:14050–14055. 10.1073/pnas.0704014104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C.H., Jun C.B., Ro S.H., Kim Y.M., Otto N.M., Cao J., Kundu M., and Kim D.H.. 2009. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:1992–2003. 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juris L., Montino M., Rube P., Schlotterhose P., Thumm M., and Krick R.. 2015. PI3P binding by Atg21 organises Atg8 lipidation. EMBO J. 34:955–973. 10.15252/embj.201488957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkin V., Lamark T., Sou Y.S., Bjørkøy G., Nunn J.L., Bruun J.A., Shvets E., McEwan D.G., Clausen T.H., Wild P., et al. 2009. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol. Cell. 33:505–516. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno H., Konno K., and Barber G.N.. 2013. Cyclic dinucleotides trigger ULK1 (ATG1) phosphorylation of STING to prevent sustained innate immune signaling. Cell. 155:688–698. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korac J., Schaeffer V., Kovacevic I., Clement A.M., Jungblut B., Behl C., Terzic J., and Dikic I.. 2013. Ubiquitin-independent function of optineurin in autophagic clearance of protein aggregates. J. Cell Sci. 126:580–592. 10.1242/jcs.114926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyei G.B., Dinkins C., Davis A.S., Roberts E., Singh S.B., Dong C., Wu L., Kominami E., Ueno T., Yamamoto A., et al. 2009. Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 186:255–268. 10.1083/jcb.200903070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K.K., Zheng X., Forestieri R., Balgi A.D., Nodwell M., Vollett S., Anderson H.J., Andersen R.J., Av-Gay Y., and Roberge M.. 2012. Nitazoxanide stimulates autophagy and inhibits mTORC1 signaling and intracellular proliferation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002691 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., Desplats P., Sigurdson C., Tsigelny I., and Masliah E.. 2010. Cell-to-cell transmission of non-prion protein aggregates. Nat Rev Neurol. 6:702–706. 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.J., Cho E.D., Lee K.W., Kim J.H., Cho S.G., and Lee S.J.. 2013. Autophagic failure promotes the exocytosis and intercellular transfer of α-synuclein. Exp. Mol. Med. 45:e22 10.1038/emm.2013.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Tang Y., Fan Z., Meng Y., Yang G., Luo J., and Ke Z.J.. 2013. Autophagy is involved in oligodendroglial precursor-mediated clearance of amyloid peptide. Mol. Neurodegener. 8:27 10.1186/1750-1326-8-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q., Seo G.J., Choi Y.J., Kwak M.J., Ge J., Rodgers M.A., Shi M., Leslie B.J., Hopfner K.P., Ha T., et al. 2014. Crosstalk between the cGAS DNA sensor and Beclin-1 autophagy protein shapes innate antimicrobial immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. 15:228–238. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J., Lachenmayer M.L., Wu S., Liu W., Kundu M., Wang R., Komatsu M., Oh Y.J., Zhao Y., and Yue Z.. 2015. Proteotoxic stress induces phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 by ULK1 to regulate selective autophagic clearance of protein aggregates. PLoS Genet. 11:e1004987 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longatti A., Lamb C.A., Razi M., Yoshimura S., Barr F.A., and Tooze S.A.. 2012. TBC1D14 regulates autophagosome formation via Rab11- and ULK1-positive recycling endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 197:659–675. 10.1083/jcb.201111079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K., Psakhye I., and Jentsch S.. 2014. Autophagic clearance of polyQ proteins mediated by ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors of the conserved CUET protein family. Cell. 158:549–563. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupfer C., Thomas P.G., Anand P.K., Vogel P., Milasta S., Martinez J., Huang G., Green M., Kundu M., Chi H., et al. 2013. Receptor interacting protein kinase 2-mediated mitophagy regulates inflammasome activation during virus infection. Nat. Immunol. 14:480–488. 10.1038/ni.2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussignol M., Queval C., Bernet-Camard M.F., Cotte-Laffitte J., Beau I., Codogno P., and Esclatine A.. 2013. The herpes simplex virus 1 Us11 protein inhibits autophagy through its interaction with the protein kinase PKR. J. Virol. 87:859–871. 10.1128/JVI.01158-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell M.A., Jain A., Arko-Mensah J., Chauhan S., Kimura T., Dinkins C., Silvestri G., Münch J., Kirchhoff F., Simonsen A., et al. 2014. TRIM proteins regulate autophagy and can target autophagic substrates by direct recognition. Dev. Cell. 30:394–409. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanillo P.S., Ayres J.S., Watson R.O., Collins A.C., Souza G., Rae C.S., Schneider D.S., Nakamura K., Shiloh M.U., and Cox J.S.. 2013. The ubiquitin ligase parkin mediates resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature. 501:512–516. 10.1038/nature12566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H., Morino H., Ito H., Izumi Y., Kato H., Watanabe Y., Kinoshita Y., Kamada M., Nodera H., Suzuki H., et al. 2010. Mutations of optineurin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 465:223–226. 10.1038/nature08971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto G., Wada K., Okuno M., Kurosawa M., and Nukina N.. 2011. Serine 403 phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates selective autophagic clearance of ubiquitinated proteins. Mol. Cell. 44:279–289. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer K., Reyes-Robles T., Alonzo F. III, Durbin J., Torres V.J., and Cadwell K.. 2015. Autophagy mediates tolerance to Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin. Cell Host Microbe. 17:429–440. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealer R.G., Murray A.J., Shahani N., Subramaniam S., and Snyder S.H.. 2014. Rhes, a striatal-selective protein implicated in Huntington disease, binds beclin-1 and activates autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 289:3547–3554. 10.1074/jbc.M113.536912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies F.M., Huebener J., Renna M., Bonin M., Riess O., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2010. Autophagy induction reduces mutant ataxin-3 levels and toxicity in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Brain. 133:93–104. 10.1093/brain/awp292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies F.M., Fleming A., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2015. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16:345–357. 10.1038/nrn3961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita F.S., Thomas M., Sachse M., Santos A.J., Figueira R., and Holden D.W.. 2012. The Salmonella deubiquitinase SseL inhibits selective autophagy of cytosolic aggregates. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002743 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulendyke K.A., Croteau J.D., and Zink M.C.. 2014. HIV life cycle, innate immunity and autophagy in the central nervous system. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 9:565–571. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier E., Dick M.S., Dreier R.F., Schürmann N., Kenzelmann Broz D., Warming S., Roose-Girma M., Bumann D., Kayagaki N., Takeda K., et al. 2014. Caspase-11 activation requires lysis of pathogen-containing vacuoles by IFN-induced GTPases. Nature. 509:366–370. 10.1038/nature13157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau K., Ravikumar B., Renna M., Puri C., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2011. Autophagosome precursor maturation requires homotypic fusion. Cell. 146:303–317. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau K., Fleming A., Imarisio S., Lopez Ramirez A., Mercer J.L., Jimenez-Sanchez M., Bento C.F., Puri C., Zavodszky E., Siddiqi F., et al. 2014. PICALM modulates autophagy activity and tau accumulation. Nat. Commun. 5:4998 10.1038/ncomms5998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowy S., Sancho-Shimizu V., Hamon M.A., Simeone R., Brosch R., Johansen T., and Cossart P.. 2011. p62 and NDP52 proteins target intracytosolic Shigella and Listeria to different autophagy pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286:26987–26995. 10.1074/jbc.M111.223610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa I., Amano A., Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Yamaguchi H., Kamimoto T., Nara A., Funao J., Nakata M., Tsuda K., et al. 2004. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science. 306:1037–1040. 10.1126/science.1103966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K., Haspel J.A., Rathinam V.A., Lee S.J., Dolinay T., Lam H.C., Englert J.A., Rabinovitch M., Cernadas M., Kim H.P., et al. 2011. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 12:222–230. 10.1038/ni.1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier R.J., Rafi W., Cheruvu M., Powell K.R., Zaunbrecher M.A., Bornmann W., Salgame P., Shinnick T.M., and Kalman D.. 2011. Imatinib-sensitive tyrosine kinases regulate mycobacterial pathogenesis and represent therapeutic targets against tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe. 10:475–485. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H., Xiong Q., Yamamoto A., Hayashi-Nishino M., and Rikihisa Y.. 2012. Autophagosomes induced by a bacterial Beclin 1 binding protein facilitate obligatory intracellular infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:20800–20807. 10.1073/pnas.1218674109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochaba J., Lukacsovich T., Csikos G., Zheng S., Margulis J., Salazar L., Mao K., Lau A.L., Yeung S.Y., Humbert S., et al. 2014. Potential function for the Huntingtin protein as a scaffold for selective autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:16889–16894. 10.1073/pnas.1420103111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M., Yoshimori T., Suzuki T., Sagara H., Mizushima N., and Sasakawa C.. 2005. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science. 307:727–731. 10.1126/science.1106036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M., Yoshikawa Y., Kobayashi T., Mimuro H., Fukumatsu M., Kiga K., Piao Z., Ashida H., Yoshida M., Kakuta S., et al. 2011. A Tecpr1-dependent selective autophagy pathway targets bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 9:376–389. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi Y., and Munro S.. 2010. Membrane delivery to the yeast autophagosome from the Golgi-endosomal system. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:3998–4008. 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman T., Teirilä L., Lahesmaa-Korpinen A.M., Cypryk W., Veckman V., Saijo S., Wolff H., Hautaniemi S., Nyman T.A., and Matikainen S.. 2014. Dectin-1 pathway activates robust autophagy-dependent unconventional protein secretion in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 192:5952–5962. 10.4049/jimmunol.1303213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvedahl A., Alexander D., Tallóczy Z., Sun Q., Wei Y., Zhang W., Burns D., Leib D.A., and Levine B.. 2007. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe. 1:23–35. 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen K.A., Meyer C.B., Bouton A.H., and Casanova J.E.. 2014. Activation of focal adhesion kinase by Salmonella suppresses autophagy via an Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and promotes bacterial survival in macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004159 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiv S., Clausen T.H., Lamark T., Brech A., Bruun J.A., Outzen H., Øvervatn A., Bjørkøy G., and Johansen T.. 2007. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282:24131–24145. 10.1074/jbc.M702824200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parihar S.P., Guler R., Khutlang R., Lang D.M., Hurdayal R., Mhlanga M.M., Suzuki H., Marais A.D., and Brombacher F.. 2014. Statin therapy reduces the mycobacterium tuberculosis burden in human macrophages and in mice by enhancing autophagy and phagosome maturation. J. Infect. Dis. 209:754–763. 10.1093/infdis/jit550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Kashyap A.K., Jia W., He Y.W., and Schaefer B.C.. 2012. Selective autophagy of the adaptor protein Bcl10 modulates T cell receptor activation of NF-κB. Immunity. 36:947–958. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford F., Masliah E., Britschgi M., Lucin K., Narasimhan R., Jaeger P.A., Small S., Spencer B., Rockenstein E., Levine B., and Wyss-Coray T.. 2008. The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid beta accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118:2190–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilli M., Arko-Mensah J., Ponpuak M., Roberts E., Master S., Mandell M.A., Dupont N., Ornatowski W., Jiang S., Bradfute S.B., et al. 2012. TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity. 37:223–234. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponpuak M., Mandell M.A., Kimura T., Chauhan S., Cleyrat C., and Deretic V.. 2015. Secretory autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 35:106–116. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottier C., Bieniek K.F., Finch N., van de Vorst M., Baker M., Perkersen R., Brown P., Ravenscroft T., van Blitterswijk M., Nicholson A.M., et al. 2015. Whole-genome sequencing reveals important role for TBK1 and OPTN mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration without motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 10.1007/s00401-015-1436-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozueta J., Lefort R., Ribe E.M., Troy C.M., Arancio O., and Shelanski M.. 2013. Caspase-2 is required for dendritic spine and behavioural alterations in J20 APP transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 4:1939 10.1038/ncomms2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri C., Renna M., Bento C.F., Moreau K., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2013. Diverse autophagosome membrane sources coalesce in recycling endosomes. Cell. 154:1285–1299. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Py B.F., Lipinski M.M., and Yuan J.. 2007. Autophagy limits Listeria monocytogenes intracellular growth in the early phase of primary infection. Autophagy. 3:117–125. 10.4161/auto.3618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Duden R., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2002. Aggregate-prone proteins with polyglutamine and polyalanine expansions are degraded by autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:1107–1117. 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Berger Z., Vacher C., O’Kane C.J., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2006. Rapamycin pre-treatment protects against apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15:1209-1216. 10.1093/hmg/ddl036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Vacher C., Berger Z., Davies J.E., Luo S., Oroz L.G., Scaravilli F., Easton D.F., Duden R., O’Kane C.J., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2004. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat. Genet. 36:585–595. 10.1038/ng1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Moreau K., Jahreiss L., Puri C., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2010. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat. Cell Biol. 12:747–757. 10.1038/ncb2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renna M., Schaffner C., Brown K., Shang S., Tamayo M.H., Hegyi K., Grimsey N.J., Cusens D., Coulter S., Cooper J., et al. 2011. Azithromycin blocks autophagy and may predispose cystic fibrosis patients to mycobacterial infection. J. Clin. Invest. 121:3554–3563. 10.1172/JCI46095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohn T.T., Rissman R.A., Davis M.C., Kim Y.E., Cotman C.W., and Head E.. 2002. Caspase-9 activation and caspase cleavage of tau in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 11:341–354. 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D.C., Shpilka T., and Elazar Z.. 2012a. Mechanisms of autophagosome biogenesis. Curr. Biol. 22:R29–R34. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D.C., Codogno P., and Levine B.. 2012b. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11:709–730. 10.1038/nrd3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Y.N., Xu Z., Patel B., Chen Z., Chen D., Tito A., David G., Sun Y., Stimming E.F., Bellen H.J., et al. 2015. Huntingtin functions as a scaffold for selective macroautophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:262–275. 10.1038/ncb3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R.C., Tian Y., Yuan H., Park H.W., Chang Y.Y., Kim J., Kim H., Neufeld T.P., Dillin A., and Guan K.L.. 2013. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 15:741–750. 10.1038/ncb2757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagnier S., Daussy C.F., Borel S., Robert-Hebmann V., Faure M., Blanchet F.P., Beaumelle B., Biard-Piechaczyk M., and Espert L.. 2015. Autophagy restricts HIV-1 infection by selectively degrading Tat in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 89:615–625. 10.1128/JVI.02174-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T., Fujita N., Jang M.H., Uematsu S., Yang B.G., Satoh T., Omori H., Noda T., Yamamoto N., Komatsu M., et al. 2008. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature. 456:264–268. 10.1038/nature07383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T., Fujita N., Hayashi T., Takahara K., Satoh T., Lee H., Matsunaga K., Kageyama S., Omori H., Noda T., et al. 2009. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:20842–20846. 10.1073/pnas.0911267106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Floto R.A., Berger Z., Imarisio S., Cordenier A., Pasco M., Cook L.J., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2005. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 170:1101–1111. 10.1083/jcb.200504035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Perlstein E.O., Imarisio S., Pineau S., Cordenier A., Maglathlin R.L., Webster J.A., Lewis T.A., O’Kane C.J., Schreiber S.L., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2007. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:331–338. 10.1038/nchembio883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Korolchuk V.I., Renna M., Imarisio S., Fleming A., Williams A., Garcia-Arencibia M., Rose C., Luo S., Underwood B.R., et al. 2011. Complex inhibitory effects of nitric oxide on autophagy. Mol. Cell. 43:19–32. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Carroll B., Buganim Y., Maetzel D., Ng A.H., Cassady J.P., Cohen M.A., Chakraborty S., Wang H., Spooner E., et al. 2013. Impaired autophagy in the lipid-storage disorder Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Cell Reports. 5:1302–1315. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer V., Lavenir I., Ozcelik S., Tolnay M., Winkler D.T., and Goedert M.. 2012. Stimulation of autophagy reduces neurodegeneration in a mouse model of human tauopathy. Brain. 135:2169–2177. 10.1093/brain/aws143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebler M., Brown K., Hegyi K., Newton S.M., Renna M., Hepburn L., Klapholz C., Coulter S., Obregón-Henao A., Henao Tamayo M., et al. 2015. Functional drug screening reveals anticonvulsants as enhancers of mTOR-independent autophagic killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through inositol depletion. EMBO Mol. Med. 7:127–139. 10.15252/emmm.201404137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C.S., Shenderov K., Huang N.N., Kabat J., Abu-Asab M., Fitzgerald K.A., Sher A., and Kehrl J.H.. 2012. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat. Immunol. 13:255–263. 10.1038/ni.2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji-Kawata S., Sumpter R., Leveno M., Campbell G.R., Zou Z., Kinch L., Wilkins A.D., Sun Q., Pallauf K., MacDuff D., et al. 2013. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature. 494:201–206. 10.1038/nature11866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpilka T., Welter E., Borovsky N., Amar N., Mari M., Reggiori F., and Elazar Z.. 2015. Lipid droplets and their component triglycerides and steryl esters regulate autophagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer B., Potkar R., Trejo M., Rockenstein E., Patrick C., Gindi R., Adame A., Wyss-Coray T., and Masliah E.. 2009. Beclin 1 gene transfer activates autophagy and ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in alpha-synuclein models of Parkinson’s and Lewy body diseases. J. Neurosci. 29:13578–13588. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilman P., Podlutskaya N., Hart M.J., Debnath J., Gorostiza O., Bredesen D., Richardson A., Strong R., and Galvan V.. 2010. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-beta levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 5:e9979 10.1371/journal.pone.0009979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S.A., Barczak A.K., Silvis M.R., Luo S.S., Sogi K., Vokes M., Bray M.-A., Carpenter A.E., Moore C.B., Siddiqi N., et al. 2014. Identification of host-targeted small molecules that restrict intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003946 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T., Ng T.W., Wehrly T.D., Knodler L.A., and Celli J.. 2008. Brucella intracellular replication requires trafficking through the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment. Traffic. 9:678–694. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner J.A., Angot E., and Brundin P.. 2011. A deadly spread: cellular mechanisms of α-synuclein transfer. Cell Death Differ. 18:1425–1433. 10.1038/cdd.2011.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz A., Ernst A., and Dikic I.. 2014. Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 16:495–501. 10.1038/ncb2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramurthy V., Barsacchi R., Samusik N., Marsico G., Gilleron J., Kalaidzidis I., Meyenhofer F., Bickle M., Kalaidzidis Y., and Zerial M.. 2013. Integration of chemical and RNAi multiparametric profiles identifies triggers of intracellular mycobacterial killing. Cell Host Microbe. 13:129–142. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal M.C., Sasai M., Lee H.K., Yordy B., Shadel G.S., and Iwasaki A.. 2009. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen species-dependent amplification of RLR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:2770–2775. 10.1073/pnas.0807694106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston T.L., Ryzhakov G., Bloor S., von Muhlinen N., and Randow F.. 2009. The TBK1 adaptor and autophagy receptor NDP52 restricts the proliferation of ubiquitin-coated bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 10:1215–1221. 10.1038/ni.1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston T.L., Wandel M.P., von Muhlinen N., Foeglein A., and Randow F.. 2012. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature. 482:414–418. 10.1038/nature10744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarello D.A., Waxse B.J., Arden S.D., Bright N.A., Kendrick-Jones J., and Buss F.. 2012. Autophagy receptors link myosin VI to autophagosomes to mediate Tom1-dependent autophagosome maturation and fusion with the lysosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:1024–1035. 10.1038/ncb2589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicinanza M., Korolchuk V.I., Ashkenazi A., Puri C., Menzies F.M., Clarke J.H., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2015PI( 5)P regulates autophagosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 57:219–234. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.J., Huang H.Y., Huang M.P., Liou W., Chang Y.T., Wu C.C., Ojcius D.M., and Chang Y.S.. 2014. The microtubule-associated protein EB1 links AIM2 inflammasomes with autophagy-dependent secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 289:29322–29333. 10.1074/jbc.M114.559153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warby S.C., Doty C.N., Graham R.K., Carroll J.B., Yang Y.Z., Singaraja R.R., Overall C.M., and Hayden M.R.. 2008. Activated caspase-6 and caspase-6-cleaved fragments of huntingtin specifically colocalize in the nucleus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17:2390–2404. 10.1093/hmg/ddn139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R.O., Manzanillo P.S., and Cox J.S.. 2012. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell. 150:803–815. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb J.L., Ravikumar B., Atkins J., Skepper J.N., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2003. Alpha-Synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25009–25013. 10.1074/jbc.M300227200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington C.L., Ellerby L.M., Gutekunst C.A., Rogers D., Warby S., Graham R.K., Loubser O., van Raamsdonk J., Singaraja R., Yang Y.Z., et al. 2002. Caspase cleavage of mutant huntingtin precedes neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 22:7862–7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild P., Farhan H., McEwan D.G., Wagner S., Rogov V.V., Brady N.R., Richter B., Korac J., Waidmann O., Choudhary C., et al. 2011. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science. 333:228–233. 10.1126/science.1205405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A., Sarkar S., Cuddon P., Ttofi E.K., Saiki S., Siddiqi F.H., Jahreiss L., Fleming A., Pask D., Goldsmith P., et al. 2008. Novel targets for Huntington’s disease in an mTOR-independent autophagy pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4:295–305. 10.1038/nchembio.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y., Ogawa M., Hain T., Yoshida M., Fukumatsu M., Kim M., Mimuro H., Nakagawa I., Yanagawa T., Ishii T., et al. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognition. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1233–1240. 10.1038/ncb1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.R., Chan E.Y., Hu X.W., Köchl R., Crawshaw S.G., High S., Hailey D.W., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Tooze S.A.. 2006. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 119:3888–3900. 10.1242/jcs.03172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavodszky E., Seaman M.N., Moreau K., Jimenez-Sanchez M., Breusegem S.Y., Harbour M.E., and Rubinsztein D.C.. 2014. Mutation in VPS35 associated with Parkinson’s disease impairs WASH complex association and inhibits autophagy. Nat. Commun. 5:3828 10.1038/ncomms4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yu J., Pan H., Hu P., Hao Y., Cai W., Zhu H., Yu A.D., Xie X., Ma D., and Yuan J.. 2007. Small molecule regulators of autophagy identified by an image-based high-throughput screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:19023–19028. 10.1073/pnas.0709695104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.T., Shahnazari S., Brech A., Lamark T., Johansen T., and Brumell J.H.. 2009. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 targets invading bacteria to the autophagy pathway. J. Immunol. 183:5909–5916. 10.4049/jimmunol.0900441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]