Highlight

Isohydric poplars have high water-use efficiency, while anisohydric poplars show faster growth under a variable water supply, with implications for performance of the different genotypes for woody biomass production.

Key words: Bioenergy, biomass, carbon, hydraulic conductance, stomata, transpiration

Abstract

Understanding how different plants prioritize carbon gain and drought vulnerability under a variable water supply is important for predicting which trees will maximize woody biomass production under different environmental conditions. Here, Populus balsamifera (BS, isohydric genotype), P. simonii (SI, previously uncharacterized stomatal behaviour), and their cross, P. balsamifera x simonii (BSxSI, anisohydric genotype) were studied to assess the physiological basis for biomass accumulation and water-use efficiency across a range of water availabilities. Under ample water, whole plant stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (E), and growth rates were higher in anisohydric genotypes (SI and BSxSI) than in isohydric poplars (BS). Under drought, all genotypes regulated the leaf to stem water potential gradient via changes in gs, synchronizing leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf) and E: isohydric plants reduced Kleaf, gs, and E, whereas anisohydric genotypes maintained high Kleaf and E, which reduced both leaf and stem water potentials. Nevertheless, SI poplars reduced their plant hydraulic conductance (Kplant) during water stress and, unlike, BSxSI plants, recovered rapidly from drought. Low gs of the isohydric BS under drought reduced CO2 assimilation rates and biomass potential under moderate water stress. While anisohydric genotypes had the fastest growth under ample water and higher photosynthetic rates under increasing water stress, isohydric poplars had higher water-use efficiency. Overall, the results indicate three strategies for how closely related biomass species deal with water stress: survival-isohydric (BS), sensitive-anisohydric (BSxSI), and resilience-anisohydric (SI). Implications for woody biomass growth, water-use efficiency, and survival under variable environmental conditions are discussed.

Introduction

Society’s dependence on fossil fuels contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and environmental pollution, leading to a demand for renewable energy sources. Woody biomass represents a renewable resource with multiple industrial applications that can serve feedstock needs for the cellulosic energy and biofuels industry without conflicting with food production (Kenney et al., 1990), and trees are expected to account for 377 million dry tons of the 1.37 billion dry tons total biomass necessary for a 30% replacement of US petroleum consumption with biofuels by 2030 (Perlack et al., 2005). Thus, tree growth rate, which underlies dry biomass gain, is a fundamental characteristic that can be used to increase productivity in tree plantations. As hybrid poplars are among the fastest growing temperate trees in the world, they serve as a promising feedstock for biofuels and other value-added products (Sannigrahi et al., 2010). Significant efforts have therefore been invested in poplar research, including genome sequencing (Tuskan et al., 2006; Bolger et al., 2014), in an attempt to produce high-yield cultivars.

Of the environmental factors constraining tree growth rate, water is usually the most critical, and water stress restricts plant growth and yield (Bréda et al., 2006; McDowell et al., 2008). This is at least partly because water loss via transpiration (E) is an inevitable consequence of photosynthesis, via the link between CO2 diffusion into, and water flux out of, stomata (von Caemmerer and Baker, 2007). Stomatal conductance (gs) thereby acts as a key control on both tree water loss and carbon gain, while carbon gain is closely linked to biomass production. At the leaf level, the ratio between CO2 uptake and E (i.e. leaf-level water-use efficiency, WUEl) is ~3–40 µmol CO2 mmol H2O-1 across different well-watered poplar genotypes (Liang et al., 2006; Soolanayakanahally et al., 2009; Larchevêque et al., 2011), implying a more than 10-fold difference in potential carbon assimilation under a variety of soil water and evaporative demand conditions. These variations in WUEl often result mainly from variations in gs and not differences in net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) or photosynthetic capacity (Blum, 2005); therefore, an increase in WUEl usually results in reduced photosynthesis and yield (Flexas et al., 2013). Despite decades of research on stomatal physiology, the complex mechanisms that adjust stomatal aperture and regulate gs are still poorly understood although they are vital for plant function, especially when water supply is limited (Tardieu and Simonneau, 1998). Nevertheless, there seems to be general agreement that stomata sense leaf water potential (Ψleaf) so that both gs and leaf hydraulic function decline when Ψleaf decreases (Brodribb and Cochard, 2009; Domec et al., 2009).

Leaf and plant water transport capacity can be quantified in terms of leaf and whole plant hydraulic conductance (Kleaf and Kplant, respectively). Plants with high hydraulic conductance can supply water rapidly from their roots to the leaves, maximizing gs, AN, and, ultimately, productivity under well-watered conditions (Nardini and Salleo, 2000). Indeed, differences in xylem traits, such as vessel diameter and sapwood area, as well as the water potential gradient from the soil/root to the leaf may generate variation in E and gs among tree species, as well as within a species (Kleiner et al., 1992; Vivin et al., 1993; Comas et al., 2002; Wikberg and Ögren, 2004; Cocozza et al., 2010). However, when evaporative demand exceeds the ability to supply water to the transpiration stream, gs declines to protect the plant hydraulic system from cavitation (Zimmermann, 1983; Oren et al., 1999; Sperry, 2000). Consistent with earlier work documenting the coordination of gs with Kleaf (Meinzer et al., 1995), recent work has revealed that maximum gs is very sensitive to Kleaf (Ewers et al., 2000; Brodribb and Holbrook, 2003; Woodruff et al., 2007; Domec et al., 2009). As Kleaf declines, owing to cavitation or regulated changes in mesophyll conductance (Johnson et al., 2009), Ψleaf will also decline, stomata will close, and yield will be negatively affected (Sack and Holbrook, 2006). Therefore, maintaining the integrity of the root to leaf water continuum while avoiding embolism during transpiration is essential for sustaining photosynthetic gas exchange and growth in plants (Meinzer and McCulloh, 2013).

Depending on their genetically dictated molecular and physiological attributes, plants budget their water in very different ways, along a continuum that ranges from the water-conserving behaviour displayed by isohydric plants to the ‘risk-taking’ behaviour displayed by anisohydric plants (Tardieu and Simonneau, 1998; Moshelion et al., 2014; Sade and Moshelion, 2014). In isohydric species, stomata conservatively regulate plant water status by controlling the rate of water loss to the atmosphere such that it matches the capacity of the soil–plant hydraulic system to supply water to leaves. In order to decrease the risk of hydraulic dysfunction and leaf dehydration, isohydric plants maintain a constant, or nearly constant, minimum daily Ψleaf (thus reflecting a narrowing soil–leaf water potential gradient) and relative water content by reducing gs and E under water stress. Anisohydric plants, on the other hand, allow Ψleaf to decrease under drought conditions relative to a well-watered environment, thus reaching a lower Ψleaf and relative water content with rising evaporative demand and maintaining the driving force for water flow to leaves (reviewed by Moshelion et al., 2014). Yet, the physiological mechanism for the regulation of isohydric and anisohydric behaviours is not fully understood (Klein, 2014; Martínez‐Vilalta et al., 2014).

These different stomatal behaviours have implications for selecting the appropriate tree species or genotype to maximize yield and biomass production for bioenergy. Because isohydric plants are expected to reduce gs as soil water becomes limiting, water loss and growth rates should also be reduced. Consequently, higher WUEl can be expected in isohydric plants than in anisohydric plants as soil dries, implying that isohydric trees would not maximize yield on a plantation, though they may be the most water-use efficient trees for producing biomass. By contrast, under prolonged severe drought, isohydric trees might be expected to survive, whereas anisohydric trees are expected to die, generating no yield at all (reviewed by Moshelion et al., 2014). Although hybrid poplars are generally considered to be relatively isohydric (Tardieu and Simonneau, 1998), they actually vary widely in their stomatal sensitivity to soil and air drying and susceptibility to xylem cavitation (Arango-Velez et al., 2011; Silim et al., 2009).

In this work, three poplar genotypes were assessed to determine how fundamental differences in stomatal behaviour, photosynthesis, leaf hydraulics, and leaf size affect growth, drought tolerance, water-use efficiency, and drought recovery rate with the goal of identifying stomatal strategies to maximize biomass productivity under variable water supplies. The genotypes used were Populus balsamifera L. (BS), a North American boreal species that maintains a constant Ψleaf under mild water stress (Almeida-Rodriguez et al., 2010), and is considered isohydric; Populus simonii carr. (SI), a fast-growing Asian species that has unknown stomatal regulation behaviour; and their cross, P. balsamifera x simonii (BSxSI), which has been reported to act in an anisohydric manner (Almeida-Rodriguez et al., 2010). Previous studies reported physiological differences in AN, gs, and WUEl, and molecular differences (e.g. aquaporin expression) between BS and BSxSI exposed to a range of water stress (Soolanayakanahally et al., 2009; Almeida-Rodriguez et al., 2010), despite their close genetic relationship. It was hypothesized that isohydric poplars would produce less biomass but have greater WUEl, and therefore would have greater survival and recovery, than anisohydric plants in response to prolonged water deprivation. By contrast, anisohydric poplars would accumulate more biomass under no water stress, as well as mild to moderate drought stress, owing to the maintenance of high gs and AN under low Ψleaf, but would have low survival rates during prolonged drought. It was also hypothesized that the reduction of Ψleaf in anisohydric plants would result from the coordinated maintenance of high Kleaf and high gs as water stress progressed.

Methods

Complementary experiments were conducted in two locations, Duke University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, using a single set of cuttings from dormant stems of the three poplar genotypes (supplied by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada) that were split between the two locations.

Duke University, NC, USA

Stem cuttings were put into 3.9L pots filled with Fafard 52 mix potting soil (www.sungro.com; Agawam, MA, USA) and grown in the Duke University Phytotron greenhouses for ~4 months to root and establish leaves. Plants were then moved to fully controlled conditions [25/20°C day/night, 18/6h light/dark, 70% relative humidity (RH), and 700 µmol photons m-2 s-1] in growth chambers (Environmental Growth Chambers, Chagrin Falls, OH, USA), and were watered as needed to maintain a moist growing medium and fertilized with half-strength Hoagland’s solution once per week. Gravimetric soil water content (SWCg) was calculated as the ratio of the mass of water in the soil sample to the mass of dry soil.

The growth rate was measured on well-watered trees grown in 0.3L pots maintained in these growth chambers. Cuttings with one lateral bud were grown for 62–65 days (until they were 30–40cm tall) and then cut at the soil surface and weighed for fresh weight. The mass of each shoot was normalized to its stem diameter (mean of three measurements taken at the soil surface level with digital callipers). Leaf size and total leaf area per plant were measured on the same trees using a leaf area meter (Li-3100; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Stomatal density measurements were made on a subset of leaves using a rapid imprinting technique (Geisler and Sack, 2002), which allowed the reliable scoring of hundreds of stomata at the same time. In brief, light-bodied vinyl polysiloxane dental resin (Heraeus-Kulzer, http://heraeus-dental.com) was attached to the abaxial and adaxial leaf sides and then removed as soon as it had dried (1min). The resin epidermal imprints were covered with transparent nail polish, which was removed once it had dried. The nail-polish imprints were put on microscope slides and photographed under a bright-field inverted microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager, http://www.zeiss.com) with a QImaging MicroPublisher 5.0 MP colour camera (http://www.qimaging.com). Stomatal images were analysed using IMAGEJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Photosynthetic capacity was assessed on five well-watered individuals per genotype with a portable photosynthesis system (Li-6400; LI-COR). Responses of AN to changes in intercellular CO2 concentrations were made at a leaf temperature of 25°C, a vapor pressure deficit of ~1.6 kPa, and saturating light (1500 µmol m-2 s-1 photosynthetic photon flux density); ambient cuvette CO2 concentrations were lowered stepwise from 400 to 50 µmol mol-1, returned to 400 µmol mol-1, and subsequently raised stepwise to 2000 µmol mol-1. Both maximum Rubisco carboxylation rates (Vcmax) and maximum electron transport rates (Jmax) values were calculated according to Farquhar et al. (1980), using Rubisco kinetic parameters from von Caemmerer et al. (1994).

When the plants were ~1 m tall, they were moved to a semi-controlled greenhouse (18/6h light/dark, 50–60% RH, 25°C and natural irradiance). Measurements took place from June to August 2013. The plants were exposed to progressive reductions in SWCg encompassing three categories of water stress based on the lowest SWCg measured in most plants (~30% SWCg) and on SWCg at field capacity (>70% SWCg): 70–100% SWCg, 50–69% SWCg, and 30–49% SWCg. Note that the values in the high SWCg class were always >70% but remained mostly <85%. The SWCg was continuously measured with Theta Probes (model ML2x; Delta-T Devices Ltd, Cambridge, UK) connected to a CR10 data logger (Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA). These SWCg values were then used to calculate Ψsoil based on a ‘dynamic’ water retention function, obtained by pairing the values of water content and a water pressure head placed in the pot at a given time (Klute, 2003).

Unless mentioned otherwise, all measurements during the dry-down experiment were taken from randomly selected individuals from each genotype. The drought treatments at Duke lasted 5 days maximum for each plant, and involved 42 BS plants, 121 BSxSI plants, and 43 SI plants. For a selected plant, point measurements of gs, E, and AN were made with a portable photosynthesis system (Li-6400; LI-COR) between 09:00 and 12:00 hours, with the cuvette set to growth conditions in the greenhouse. Immediately after, Ψleaf was assessed with a Scholander pressure chamber (PMS Instruments, Albany, OR, USA) and the stem water potential (Ψstem) was estimated using the bagged-sealed leaf technique (Begg and Turner, 1970). These values were used to estimate Kleaf and Kplant as described in Equations 1 and 2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot, Israel

A similar set of cuttings from the same three poplar genotypes were grown in Israel to determine whole plant water use and responses to drought. Whole plant daily transpiration (DT) and growth were determined using an array of lysimeters placed in a greenhouse at the Faculty of Agriculture, Rehovot, Israel, as described in detail previously (Sade et al., 2009). Briefly, cuttings were planted in 3.9L pots filled with potting soil and grown under semi-controlled conditions of 30/25°C day/night under natural day length and light in Rehovot, Israel, from April to May 2014, with ample water supply. Each pot was placed on a temperature-compensated load cell with a digital output (Vishay Tedea-Huntleigh, Netanya, Israel), and was sealed to prevent evaporation from the soil surface. The weight output of the load cells was monitored every 15 s and the average readings over 3min periods were logged (Campbell Scientific CR1000 Data Logger) for further analysis. DT was assessed as the difference in mass between 04:30 and 18:00 hours.

A drainage hole at the base of the lysimeters maintained a constant water level following irrigation events, enabling the calculation of the weight gained by the plant (ΔPWk) between two consecutive irrigation events as described in Equation 3:

| (3) |

where Wk and Wk+1 are the total weight of the pot placed on the lysimeter on two consecutive days (days k and k+1). Therefore, the plant weight gain over the entire experiment period was the sum of the daily plant weight gains from the first to the last day. Agricultural water use efficiency (WUEa) was calculated as the cumulative weight gain over cumulative transpiration during measurements days as describe in Equation 4:

| (4) |

The plants were watered daily until the onset of drought treatment, where no watering was applied until the SWCg in each pot fell below 30%. Because the trees growing in Israel were smaller than those at Duke, the drought varied between 10 and 20 days in duration (depending on plant size); the number of individuals from each genotype varied based on initial availability, and survival during growth and drought (four from BS, 20 from BSxSI, 15 from SI). Once SWCg fell below 30%, watering was reinitiated. Recovery patterns from severe drought stress (SWCg <30%) were determined as the proportion of DT after the return of irrigation to each plant compared to maximal DT prior to drought treatment.

Statistical analyses

Shapiro–Wilk tests for normal distribution of the data were made prior to Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests used for comparisons of means; comparison to controls were made using the Dunnett’s method. Both tests were considered to be significantly different at P < 0.05; all statistics were analysed with JMP 10 Pro (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

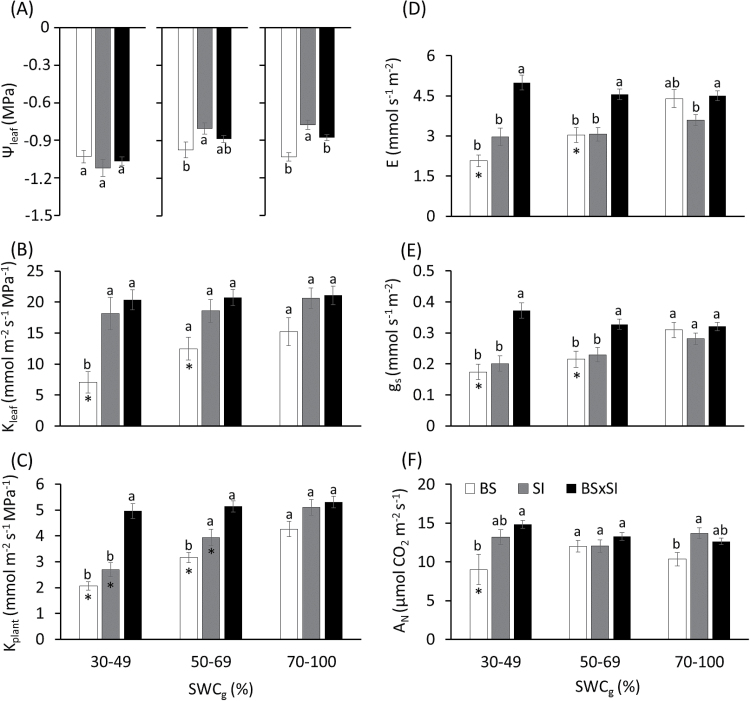

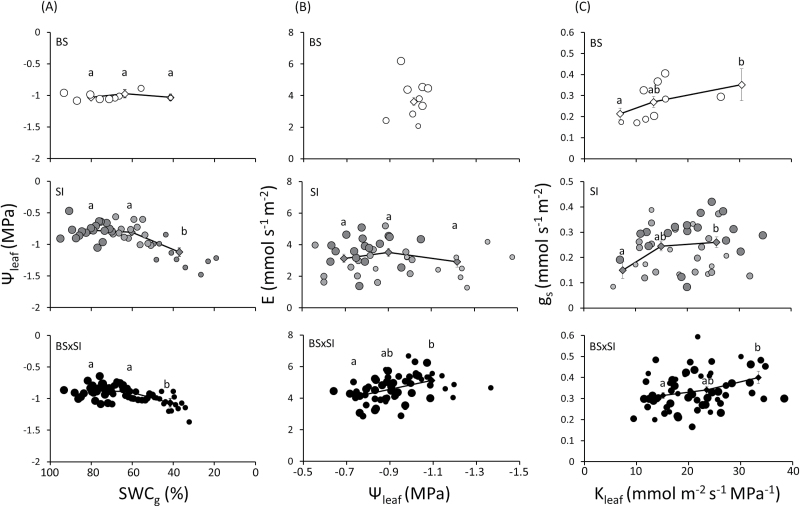

Under well-watered conditions (70–100% SWCg), Ψleaf of the SI was significantly less negative than the BS and BSxSI, but Ψleaf differences between the three genotypes disappeared at 30–49% SWCg (Fig. 1A). Thus, only the BS presented isohydric behaviour, maintaining constant Ψleaf with declining SWCg (Fig. 2A), and the stem water potential (Ψstem) showed the same tendency (Supplementary Fig. 1A). As a consequence, the water potential difference between the stem and the leaf (∆Ψleaf) did not vary between the three genotypes: ∆Ψleaf remained constant as SWCg decreased, generating a constant driving force (of around 0.3MPa) for water flow from the stem to the leaf (Supplementary Fig. 1B). This behaviour was made possible by the fact that the BS sharply reduced E and gs in response to the declining SWCg, while BSxSI and SI kept higher E and gs as water depletion progressed, and were thus insensitive to the declining Ψleaf (Figs 1D,E and 2A,B).

Fig. 1.

Mean differences in (A) Ψleaf, (B) Kleaf, (C) Kplant, (D) E, (E) gs, and (F) AN in three poplar genotypes under three SWCg treatments grown in a semi-controlled greenhouse. Data are shown as means ± SE (BS; n = 42), (SI; n = 210), and BSxSI (n = 311). Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences between the three poplar genotypes within an SWCg bin according to Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05. Asterisks indicate significant differences in comparisons within a genotype to well-irrigated controls using Dunnett’s method, P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between (A) SWCg and Ψleaf, (B) Ψleaf and E, and (C) Kleaf and gs in three poplar genotypes grown in a semi-controlled greenhouse. Data binned by SWCg, every circle is a 5 point average: large circles, 70–100% SWCg, medium circles, 50–69% SWCg, small circles, 30–49% SWCg. BS (n = 42), SI (n = 210), BSxSI (n = 311). Lines connect the mean ± SE of the SWCg bins (30–49%, 50–69%, 70–100%). Different letters above the SE bars indicate significant differences between means using Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05.

Kleaf showed a similar pattern to E and gs; while SI and BSxSI kept Kleaf relatively constant as SWCg declined, BS Kleaf decreased by ~50% under the same conditions (Fig. 1B). Thus, gs declined in concert with the decrease in Kleaf in the isohydric BS genotype, but gs was less tightly correlated with decreases in Kleaf in the two anisohydric poplars (Fig. 2C). Only the BSxSI maintained constant Kplant as SWCg decreased (Fig. 1C).

There were no significant differences in the photosynthetic capacity between the genotypes, as measured by maximum Vcmax Jmax (means ± SE: Vcmax = 125.7±5.2 µmol CO2 m-2 s-1; Jmax = 167.8±8.6 µmol CO2 m-2 s-1). However, instantaneous measurements of AN in the greenhouse revealed that the SI had a higher AN at 70–100% and the BS had the lowest AN at 30–49% SWCg (Fig. 1F).

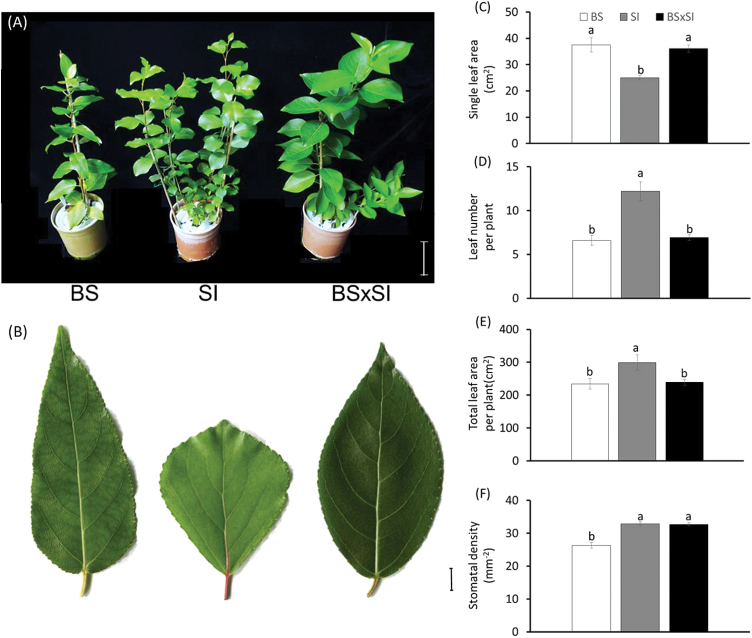

The different genotypes varied in leaf size and number (Fig. 3A,B). BS and BSxSI had bigger leaves than SI seedlings (Fig 3B,C), but SI plants had more leaves per plant, such that there was a larger total leaf area in SI plants than in the other two genotypes (Fig 3D,E). Owing to its lower total leaf area and stomatal density (Fig. 3F), BS plants had the lowest stomatal number per plant (i.e. the gas exchange capacity per plant), while SI seedlings had the highest. Under well-watered conditions, the BS genotype also had significantly lower growth rates than the two anisohydric genotypes (Figure 4D).

Fig. 3.

Canopy and leaf morphology characteristics of the three poplars genotypes: (A) image of representative 5-month-old seedlings grown in a semi-controlled greenhouse and used for the experiments (bar = 10cm); (B) representative fully mature, expanded leaves (bar = 1cm); (C) single leaf area; (D) leaf number per plant; (E) total canopy area per plant; and (F) stomatal density in a 1mm2 sample area. Data are shown as means ± SE; BS (n = 14), SI (n = 18), BSxSI (n = 34). Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences between treatments using Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05 (this figure is available in colour at JXB online).

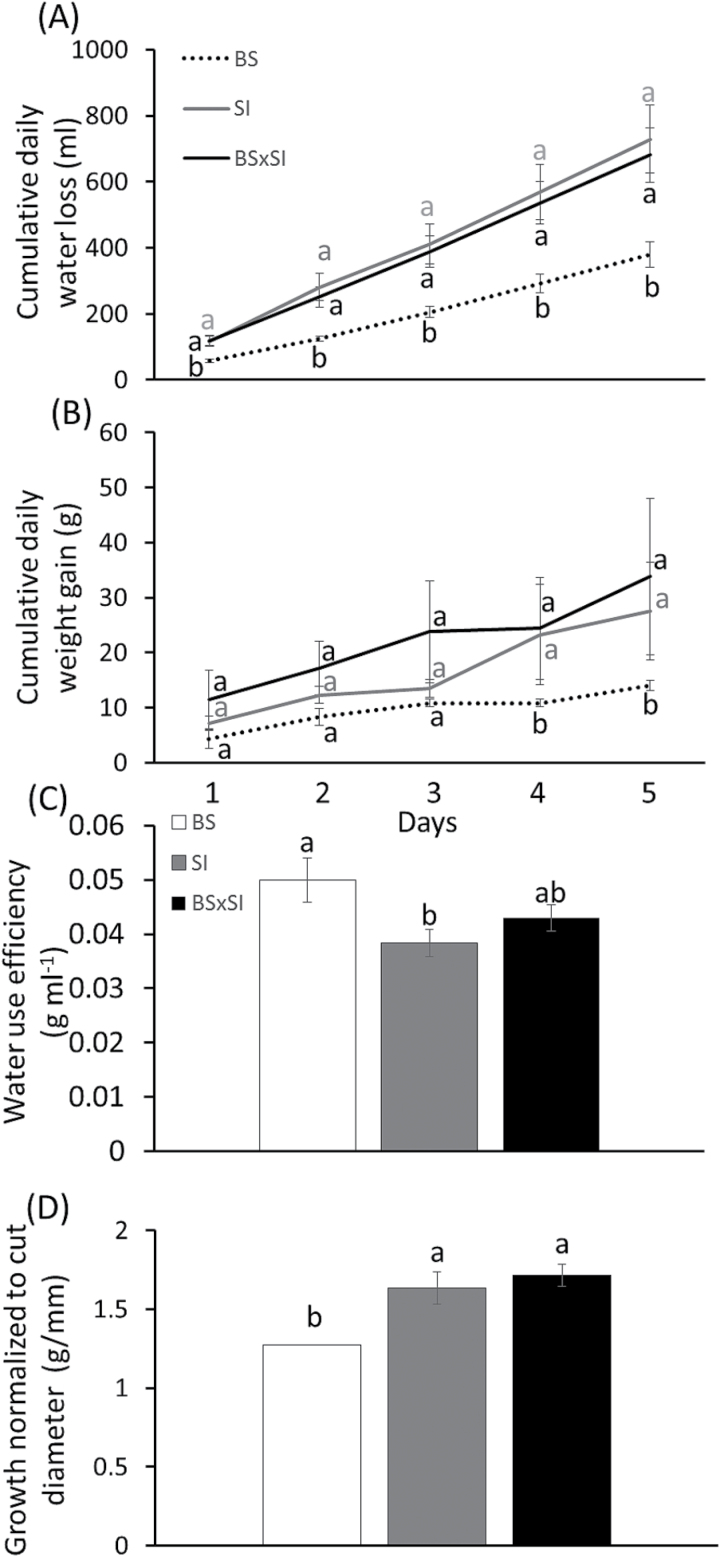

Fig. 4.

(A) Whole-plant cumulative water loss, (B) cumulative plant weight gain, (C) agricultural WUE (cumulative transpiration to cumulative weight gain ratio), and (D) growth normalized to cut diameter (g fresh mass/mm) in three poplar genotypes grown under well-irrigated conditions in a semi-controlled greenhouse. Data are shown as means ± SE: for (A-C), BS (n = 4), SI (n = 15), and BSxSI (n = 19); for (D) BS (n = 5), SI (n = 6), and BSxSI (n = 16). White, BS; grey, SI; black, BSxSI. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences between the genotypes for each day, according to Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05.

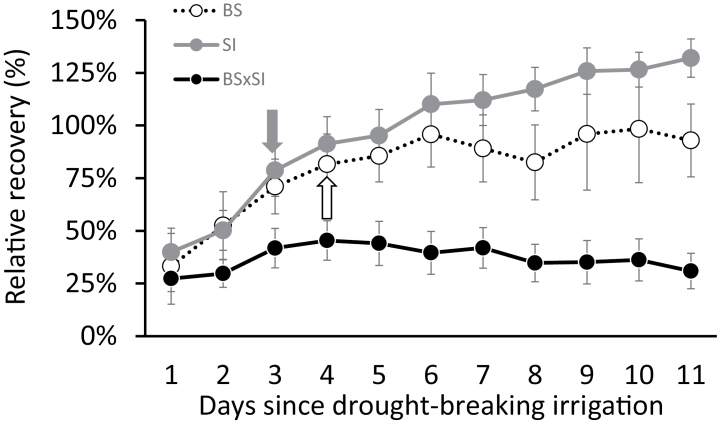

To better understand how these morphological and physiological differences contribute to plant growth rates, water-use efficiency, and drought tolerance, whole-plant transpiration, growth rate, and WUEa were measured. The SI and BSxSI had higher cumulative transpiration and weight gain than the BS under well-watered conditions (Fig. 4A,B,D), which did not correspond with a higher leaf-level E and gs (Fig. 1D,E), but could be explained by considering the different canopy morphology and stomatal densities between the genotypes (Fig. 3). However, the isohydric BS gained more biomass for a given amount of water transpired, generating a higher WUEa compared to the anisohydric SI plants (Fig 4C). The recovery patterns from severe water stress (reaching SWCg <30%) showed that the BS and SI fully recovered within 3–4 days of irrigation, while the BSxSI did not recover to their initial transpiration rates even after 11 days of irrigation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Recovery rate (relative to pre-treatment transpiration level) from water deprivation of ~30% SWCg. Data are shown as means ± SE: BS (n = 4), SI (n = 15), and the BSxSI (n = 19). Arrows (with colours matching the symbols for the respective genotypes) indicate when post-stress transpiration rates were not significantly different from the pre-treatment values according to a Student t-test, P < 0.05.

Discussion

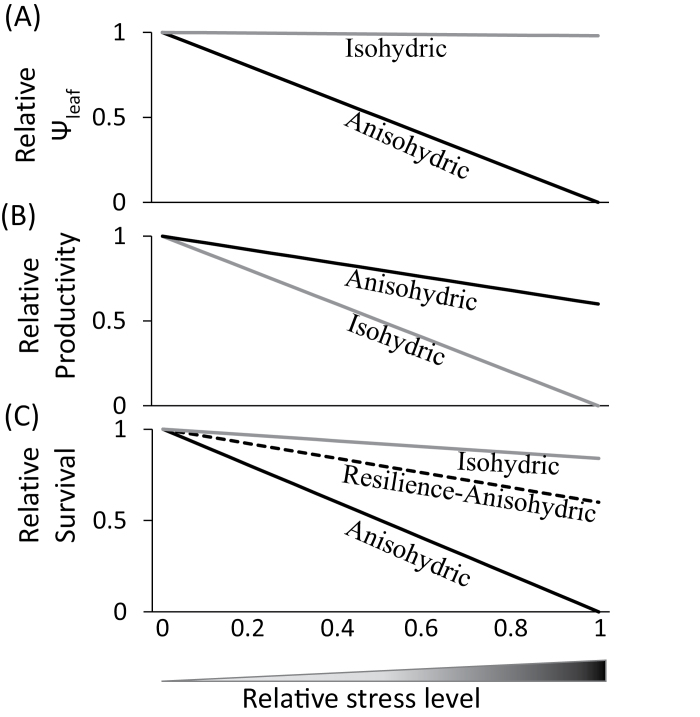

This study demonstrates that three genotypes of poplar, a key woody biomass species, have different strategies to cope with drought stress, with implications for their suitability for biomass production. The contrasting stomatal and leaf hydraulic behaviours between genotypes ranged from a rapidly responding isohydric behaviour (BS), which is hypothesized to increase survival under drought at the cost of low biomass production, to an anisohydric behaviour (SI and BSxSI) that is thought to allow carbon uptake and maintain high growth rates for a longer period during drought, but to expose the plant to greater risk of drought-induced mortality if the drought persists. Overall, the results indicated three strategies for how the closely related biomass genotypes deal with water stress: survival-isohydric, sensitive-anisohydric, and resilience-anisohydric (Fig. 6). By reducing hydraulic and stomatal conductance to maintain a constant Ψleaf, the isohydric poplars minimized the exposure of their leaves to water stress, but also decreased their ability to fix carbon for growth as the soil dried. By contrast, the anisohydric plants kept a high AN while Ψleaf declined, which should enable higher productivity in the anisohydric poplars, but also made them more vulnerable to damage from prolonged drought stress (Figs 2, 4, 5, 6). Given that recent work in 37 hybrid and pure species of poplar has shown that mean water potentials at which 50% of conductivity is lost range between −1.3 and −1.5MPa, with a large number of hybrids losing 50% of conductivity at water potentials >−1MPa (Fichot et al., 2015), the Ψstem values of near −0.9MPa shown here were likely sufficient to induce significant cavitation.

Fig. 6.

Conceptual model for behaviour of isohydric versus anisohydric plants by means of regulating (A) Ψleaf, (B) productivity, and (C) survival in response to increasing relative water stress, which accounts for changes in the SWCg and the period of time water stress was applied (this figure is available in colour at JXB online).

While the ability of the isohydric BS to maintain high Ψleaf and Ψstem in both well-irrigated and drought conditions compared to the anisohydric BSxSI (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1A) has already been documented (Almeida-Rodriguez et al., 2010), the stomatal strategy of the SI has not. Here, the paternal SI demonstrated the opposite water balance regulation strategy to the maternal BS used to generate the crosses. The conservative water balance regulation of BS comes at the cost of slower growth rates (Figs 1F and 4B,D), which should be exacerbated by a fast reduction in E, gs, Kleaf, and AN as soil dries, as hypothesized. Yet, the BS plants benefitted from this behaviour through their ability to maintain a high Ψleaf under dry soils and, if subjected to drought, BS plants recovered faster than the anisohydric BSxSI cross (Fig. 5), and will thus likely have higher survival in dry conditions. By contrast, the anisohydric behaviour of the SI and BSxSI plants enabled them to sustain faster growth rates (Fig. 4B,D) through longer periods of high E and gs as water availability declined (Supplementary Fig. 1A,B, Fig. 4B,D). This, in turn, enabled longer periods of high AN as SWCg decreased (Fig. 1F), making these poplars more suited for high biomass productivity. In fact, this anisohydric behaviour was suggested to be an agronomic trait, because anisohydric plants may outperform isohydric plants in terms of growth and yield (McDowell et al., 2008; Sade et al., 2009; Sade et al., 2012). As hypothesized, the reduction in Ψleaf of the SI and BSxSI plants was possible by maintaining high Kleaf (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, the risk of keeping high hydraulic conductance as well as high gs during deteriorating SWCg might be hydraulic failure. Thus, under short-term stress conditions, the cost of anisohydry should be slow drought recovery (as seen in the BSxSI), and if the stress is prolonged, possible tree mortality.

Interestingly, despite the fact that the SI and BSxSI presented very similar anisohydric stomatal regulation (and therefore similar growth patterns), SI plants showed much better recovery from drought compared with the BSxSI plants (Fig. 5). With all else being equal, leaf and whole-plant tolerance to low SWCg should be conferred by the ability to provide transport pathways from major veins to the sub-stomatal cavity, which is generally associated with small leaf size (McKown et al., 2010; Scoffoni et al., 2011), and big leaved plants are less adapted to dry habitats (Gibson, 1998; Ackerly, 2004). Therefore, the greater drought recovery ability of the SI may be partly due to its smaller leaves, although other parameters, such as its ability to maintain high Kleaf while reducing its Kplant during drought, might also serve as embolism defence mechanisms (Domec and Johnson, 2012). The fact that BSxSI poplars maintained high Kleaf and Kplant (but suffered from slow water-stress recovery), while both Kleaf and Kplant were reduced in BS poplars (Fig. 1B,C), supports this hypothesis. In addition, the ability of the SI to maintain relatively low E but relatively high AN for longer periods under drought, together with the larger SI leaf area per plant, provides additional advantages for growth under drought.

Poplars are long-lived trees characterized by a dioecious breeding system, wind dispersal of pollen and seeds, clonality, and often continental-scale distribution; as a result, poplars potentially comprise interbreeding populations of immense size. These life history traits typify a plant expected to exhibit abundant genetic variation (Breen et al., 2009), and hybrid poplars are a promising feedstock for multiple industrial applications (Sannigrahi et al., 2010) owing to their large germplasm and their status as the model species for tree genomics (Tuskan et al., 2006). In the long developmental process of breeding new tree genotypes, understanding the physiological responses of the plants to their intended growth environment is a crucial step to developing appropriate cultivars for commercial plantations. Under high soil moisture, anisohydric poplars (such as the SI and BSxSI) had a clear advantage because of their faster growth and higher photosynthetic rates, which may facilitate higher biomass production. Yet increasing demand for food and energy, combined with rising pressure for land conversion, may affect productivity (Harvey and Pilgrim, 2011) as biomass crops are grown on increasingly marginal lands to prevent competition with food production (Murphy et al., 2011; Swinton et al., 2011). Under these conditions, planting the isohydric BS is preferable, because it has high water-use efficiency and is able to grow and survive under poorer conditions, although its performance is limited in terms of growth.

While the implications of varied stomatal regulation strategies for growth, water-use efficiency, and survival under a variable environment should be tested in the field, the SI’s dynamic resilience-anisohydric behaviour patterns (Fig. 6) might be the ultimate strategy for growing under mild to moderate drought conditions, and may provide a suitable role model for future development in woody biomass production.

Supplementary data

Figure S1: The effect of SWCg on (A) Ψleaf and (B) the difference between Ψstem and Ψleaf of three poplar genotypes. Data is shown as means ± SE from at least 20 independent measuring days and 24 technical repetitions per day. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences between treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05. Asterisks indicate significant differences within a genotype in comparisons to well-irrigated controls using Dunnett’s method, P < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

We thank Raju Soolanayakanahally from Agriculture Canada for supplying the cuttings for this experiment, and Barb Thomas and Alberta-Pacific Forestry Industries for their kind support. The work was supported by funding to JCD, MM, RO, and DAW from the US–Israeli Bi-national Science Foundation (#2010320). This work was also supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (#EAR-1344703) to JCD, from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation to DAW, as well as the US Department of Agriculture, AFRI (#2011-67003-30222) and the US Department of Energy, Terrestrial Ecosystem Sciences (#11-DE-SC-0006967) to RO and DAW.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AN

net CO2 assimilation rate

- DT

whole plant daily transpiration

- E

transpiration rate

- gs

stomatal conductance

- Jmax

maximum electron transport rates

- Kleaf

leaf hydraulic conductance

- Kplant

plant hydraulic conductance

- Ψleaf

leaf water potential

- Ψsoil

soil water potential

- Ψstem

stem water potential

- SWCg

gravimetric soil water content

- Vcmax

maximum Rubisco carboxylation rates

- Wk

pot weight on day k

- WUEa

agronomic water use efficiency

- WUEl

leaf-level water-use efficiency.

References

- Ackerly DD. 2004. Adaptation, niche conservatism, and convergence: comparative studies of leaf evolution in the California chaparral. The American Naturalist 163, 654–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Rodriguez AM, Cooke JEK, Yeh F, Zwiazek JJ. 2010. Functional characterization of drought-responsive aquaporins in Populus balsamifera and Populus simonii×balsamifera clones with different drought resistance strategies. Physiologia Plantarum 140, 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Velez A, Zwiazek JJ, Thomas BR, Tyree MT. 2011. Stomatal factors and vulnerability of stem xylem to cavitation in poplars. Physiologia Plantarum 143, 154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg JE, Turner NC. 1970. Water potential gradients in field tobacco. Plant Physiology 46, 343–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. 2005. Drought resistance, water-use efficiency, and yield potential—are they compatible, dissonant, or mutually exclusive? Crop and Pasture Science 56, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger ME, Weisshaar B, Scholz U, Stein N, Usadel B, Mayer KF. 2014. Plant genome sequencing—applications for crop improvement. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 26, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bréda N, Huc R, Granier A, Dreyer E. 2006. Temperate forest trees and stands under severe drought: a review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Annals of Forest Science 63, 625–644. [Google Scholar]

- Breen AL, Glenn E, Yeager A, Olson MS. 2009. Nucleotide diversity among natural populations of a North American poplar (Populus balsamifera, Salicaceae). New Phytologist 182, 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Cochard H. 2009. Hydraulic failure defines the recovery and point of death in water-stressed conifers. Plant Physiology 149, 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM. 2003. Stomatal closure during leaf dehydration, correlation with other leaf physiological traits. Plant Physiology 132, 2166–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocozza C, Cherubini P, Regier N, Saurer M, Frey B, Tognetti R. 2010. Early effects of water deficit on two parental clones of Populus nigra grown under different environmental conditions. Functional Plant Biology 37, 244–254. [Google Scholar]

- Comas L, Bouma T, Eissenstat D. 2002. Linking root traits to potential growth rate in six temperate tree species. Oecologia 132, 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domec J-C, Johnson DM. 2012. Does homeostasis or disturbance of homeostasis in minimum leaf water potential explain the isohydric versus anisohydric behavior of Vitis vinifera L. cultivars? Tree Physiology 32, 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domec JC, Palmroth S, Ward E, Maier CA, Thérézien M, Oren R. 2009. Acclimation of leaf hydraulic conductance and stomatal conductance of Pinus taeda (loblolly pine) to long-term growth in elevated CO2 (free-air CO2 enrichment) and N-fertilization. Plant, Cell & Environment 32, 1500–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewers B, Oren R, Sperry J. 2000. Influence of nutrient versus water supply on hydraulic architecture and water balance in Pinus taeda . Plant, Cell & Environment 23, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C 3 species. Planta 149, 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichot R, Brignolas F, Cochard H, Ceulemans R. 2015. Vulnerability to drought-induced cavitation in poplars: synthesis and future opportunities. Plant, Cell & Environment, epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Niinemets Ü, Gallé A, Barbour M, Centritto M, Diaz–Espejo A, Douthe C, Galmés J, Ribas-Carbo M, Rodriguez P, Rosselló F, Soolanayakanahally R, Tomas M, Wright I, Farquhar G, Medrano H. 2013. Diffusional conductances to CO2 as a target for increasing photosynthesis and photosynthetic water-use efficiency. Photosynthesis Research 117, 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler MJ, Sack FD. 2002. Variable timing of developmental progression in the stomatal pathway in Arabidopsis cotyledons . New Phytologist 153, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson AC. 1998. Photosynthetic organs of desert plants. BioScience 48, 911–920. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey M, Pilgrim S. 2011. The new competition for land: food, energy, and climate change. Food Policy 36, Supplement 1, S40–S51. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Woodruff DR, McCulloh KA, Meinzer FC. 2009. Leaf hydraulic conductance, measured in situ, declines and recovers daily: leaf hydraulics, water potential and stomatal conductance in four temperate and three tropical tree species. Tree Physiology 29, 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney W, Sennerby-Forsse L, Layton P. 1990. A review of biomass quality research relevant to the use of poplar and willow for energy conversion. Biomass 21, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Klein T. 2014. The variability of stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential across tree species indicates a continuum between isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Functional Ecology 28, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner KW, Abrams MD, Schultz JC. 1992. The impact of water and nutrient deficiencies on the growth, gas exchange and water relations of red oak and chestnut oak. Tree Physiology 11, 271–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klute A. 2003. Water Retention: Laboratory Methods. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America Book Series, 635–662. [Google Scholar]

- Larchevêque M, Maurel M, Desrochers A, Larocque GR. 2011. How does drought tolerance compare between two improved hybrids of balsam poplar and an unimproved native species? Tree Physiology 31, 240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang ZS, Yang JW, Shao HB, Han RL. 2006. Investigation on water consumption characteristics and water use efficiency of poplar under soil water deficits on the Loess Plateau. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 53, 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vilalta J, Poyatos R, Aguadé D, Retana J, Mencuccini M. 2014. A new look at water transport regulation in plants. New Phytologist 2014, 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell N, Pockman WT, Allen CD, Breshears DD, Cobb N, Kolb T, Plaut J, Sperry J, West A, Williams DG, Yepez EA. 2008. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytologist 178, 719–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKown AD, Cochard H, Sack L. 2010. Decoding leaf hydraulics with a spatially explicit model: principles of venation architecture and implications for its evolution. The American Naturalist 175, 447–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer F, Goldstein G, Jackson P, Holbrook N, Gutierrez M, Cavelier J. 1995. Environmental and physiological regulation of transpiration in tropical forest gap species: the influence of boundary layer and hydraulic properties. Oecologia 101, 514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer FC, McCulloh KA. 2013. Xylem recovery from drought-induced embolism: where is the hydraulic point of no return? Tree Physiology 33, 331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshelion M, Halperin O, Wallach R, Oren RAM, Way DA. 2014. Role of aquaporins in determining transpiration and photosynthesis in water-stressed plants: crop water-use efficiency, growth and yield. Plant, Cell & Environment, epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R, Woods J, Black M, McManus M. 2011. Global developments in the competition for land from biofuels. Food Policy 36, Supplement 1, S52–S61. [Google Scholar]

- Nardini A, Salleo S. 2000. Limitation of stomatal conductance by hydraulic traits: sensing or preventing xylem cavitation? Trees 15, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Oren R, Sperry J, Katul G, Pataki D, Ewers B, Phillips N, Schäfer K. 1999. Survey and synthesis of intra‐and interspecific variation in stomatal sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit. Plant, Cell & Environment 22, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Perlack RD, Wright LL, Turhollow AF, Graham RL, Stokes BJ, Erbach DC. 2005. Biomass as feedstock for a bioenergy and bioproducts industry: the technical feasibility of a billion-ton annual supply. Springfield, VA: US Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Holbrook NM. 2006. Leaf hydraulics. Annual Review of Plant Biology 57, 361–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade N, Gebremedhin A, Moshelion M. 2012. Risk-taking plants: anisohydric behavior as a stress-resistance trait. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7, 767–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade N, Moshelion M. 2014. The dynamic isohydric-anisohydric behavior of plants upon fruit development: taking a risk for the next generation. Tree Physiology 34, 1199–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade N, Vinocur BJ, Diber A, Shatil A, Ronen G, Nissan H, Wallach R, Karchi H, Moshelion M. 2009. Improving plant stress tolerance and yield production: is the tonoplast aquaporin SlTIP2;2 a key to isohydric to anisohydric conversion? New Phytologist 181, 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sannigrahi P, Ragauskas AJ, Tuskan GA. 2010. Poplar as a feedstock for biofuels: a review of compositional characteristics. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 4, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Scoffoni C, Rawls M, McKown A, Cochard H, Sack L. 2011. Decline of leaf hydraulic conductance with dehydration: relationship to leaf size and venation architecture. Plant Physiology 156, 832–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silim S, Nash R, Reynard D, White B, Schroeder W. 2009. Leaf gas exchange and water potential responses to drought in nine poplar (Populus spp.) clones with contrasting drought tolerance. Trees 23, 959–969. [Google Scholar]

- Soolanayakanahally RY, Guy RD, Silim SN, Drewes EC, Schroeder WR. 2009. Enhanced assimilation rate and water use efficiency with latitude through increased photosynthetic capacity and internal conductance in balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera L.). Plant, Cell & Environment 32, 1821–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry JS. 2000. Hydraulic constraints on plant gas exchange. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 104, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Swinton SM, Babcock BA, James LK, Bandaru V. 2011. Higher US crop prices trigger little area expansion so marginal land for biofuel crops is limited. Energy Policy 39, 5254–5258. [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu F, Simonneau T. 1998. Variability among species of stomatal control under fluctuating soil water status and evaporative demand: modelling isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Journal of Experimental Botany 49, 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A. 2006. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivin P, Aussenac G, Levy G. 1993. Differences in drought resistance among 3 deciduous oak species grown in large boxes. Annals of Forest Science 50, 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Baker N. 2007. The biology of transpiration. From guard cells to globe. Plant Physiology 143, 3. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Hudson GS, Andrews TJ. 1994. The kinetics of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta 195, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg J, Ögren E. 2004. Interrelationships between water use and growth traits in biomass-producing willows. Trees 18, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff DR, McCulloh KA, Warren JM, Meinzer FC, Lachenbruch B. 2007. Impacts of tree height on leaf hydraulic architecture and stomatal control in Douglas-fir. Plant, Cell & Environment 30, 559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann MH. 1983. Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap. Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.