Abstract

Female sex workers (FSWs) and female prisoners experience elevated HIV prevalence relative to the general population because of unprotected sex and unsafe drug use practices, but the antecedents of these behaviors are often structural in nature. We review the literature on HIV risk environments for FSWs and female prisoners, highlighting similarities and differences in the physical, social, economic, and policy/legal environments that need to be understood to optimize HIV prevention, treatment, and policy responses. Sex work venues, mobility, gender norms, stigma, debt, and the laws and policies governing sex work are important influences in the HIV risk environment among FSWs, affecting their exposure to violence and ability to practice safer sex and safer drug use behaviors. Female prisoners are much more likely to have a drug problem than do male prisoners and have higher HIV prevalence, yet are much less likely to have access to HIV prevention and treatment and access to drug treatment in prison. Women who trade sex or are imprisoned and engage in substance use should not be considered in separate silos because sex workers have high rates of incarceration and many female prisoners have a history of sex work. Repeated cycles of arrest, incarceration, and release can be socially and economically destabilizing for women, exacerbating their HIV risk. This dynamic interplay requires a multisectoral approach to HIV prevention and treatment that appreciates and respects that not all women are willing, able, or want to stop sex work or drug use. Women who engage in sex work, use drugs, or are imprisoned come from all communities and deserve sustained access to HIV prevention and treatment for substance use and HIV, helping them and their families to lead healthy and satisfying lives.

Keywords: substance use

INTRODUCTION

Global sex trade is perceived to be increasing, as is the number of female prisoners.1,2 Although global estimates of the number of female sex workers (FSWs) is lacking, a national US survey conducted in 1992 found that approximately 2% of women had ever sold sex.3 The number of incarcerated women is growing in all 5 continents, increasing by an average of 16% in the last 6 years.2 In 2012, more than 600,000 women and girls were detained in prisons worldwide, with one third in the United States.3

Many FSWs use drugs and alcohol; for some, drug dependence may have precipitated their entry into sex work, whereas others may turn to substance use to cope or numb the challenging lifestyles associated with sex work. Women who trade sex and inject or use drugs are also vastly over-represented in prison populations.4 Incarcerated women are much more likely to have a drug problem than do male prisoners and are more likely to have been imprisoned for a drug offense than incarcerated men.5 Globally, 30%–60% of females used illicit drugs in the month before entering prison compared with 10%–48% of males.4 In Latin America, 60%–80% of female prisoners are incarcerated for drug-related offenses.6 In the United States, the number of women incarcerated for drug-related offenses has increased by more than 800% over the past 30 years, compared with a 300% increase for men.3

FSWs and female prisoner populations have elevated HIV prevalence relative to the general population. In a review of 50 lower- and middle-income countries, HIV prevalence was 12 times higher among FSWs than among other women of reproductive age.7 In another review, HIV prevalence was higher in female than male inmates in 15 countries and lower than male inmates in only 7 countries.8 For example, elevated HIV prevalence among female prisoners relative to male prisoners has been reported in Uganda (13% vs 11%),9 Kenya (19.3% vs 5.5%),10 Indonesia (6% vs 1%),11 and the republic of Georgia (5% vs 1%).12

This article was motivated by the recognition that women who trade sex or are imprisoned and engage in substance use are often considered in separate silos. Although not all FSWs use drugs or are imprisoned, and not all female prisoners have engaged in drug use or sex work, we note that there is often considerable overlap between these populations. Postrelease periods are especially destabilizing for women who are current or former substance users because these periods are often characterized by a return to preincarceration behaviors that can include increases or relapses in substance use with the elevated risk of overdose, sex work, and elevated HIV incidence.13–15 In some countries, such as the United States large populations of women are under community supervision as an alternative to incarceration (ie, on probation); yet, there is little research on these populations.15,16

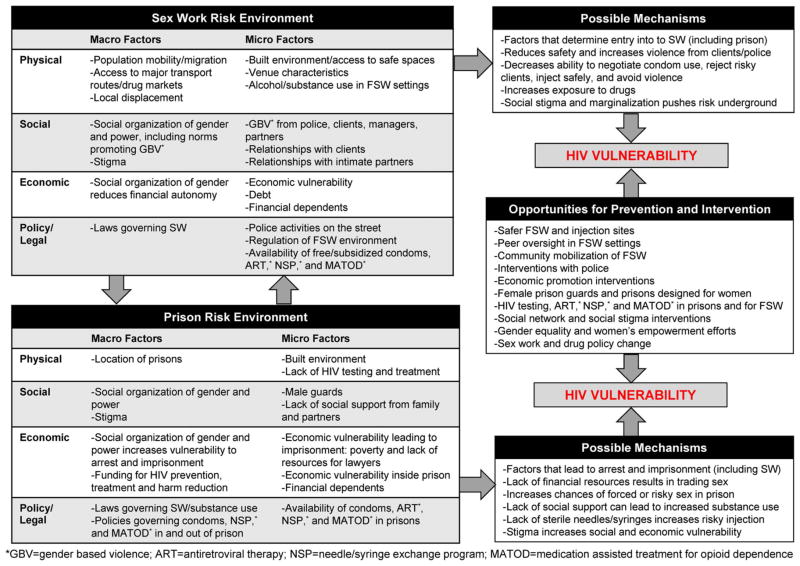

FSWs and female prisoners both experience heightened risk for HIV infection because of unprotected sex and unsafe drug use practices, but the antecedents of these behaviors are often structural in nature.5,7,17 HIV risk behaviors do not occur in a vacuum; they are influenced by risk environments, which are the social or physical spaces in which macro- and micro-level factors exogenous to the individual interact to influence HIV vulnerability.18 For example, male dominance over women in the form of gender-power imbalances, gender-based violence (GBV) and laws governing sex work and drug use are important social and policy drivers of HIV risk at the macrolevel,19 whereas the built environment of sex work establishments and prisons represent physical characteristics that influence HIV risk at the microlevel (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

HIV risk environment and opportunities for intervention and prevention among FSWs and prisoners.

Herein, we review selected literature concerning the HIV risk environment for FSWs and female prisoners, highlighting similarities and differences in the physical, social, economic, and policy environments that need to be understood to optimize HIV prevention, treatment, and policy responses for these vulnerable subgroups of women.

RISK ENVIRONMENTS FOR FSWs

Physical Influences

The physical setting in which FSWs live and work is a critical element of the HIV risk environment, such that different sex work venues afford different sets of risk or protective factors. Brothels can afford women protection from police and violence, even in settings where sex work is illegal, because managers can pay off police and supervise transactions.19 In some venues, managers promote informal policies such as offering “ladies drinks” with lower alcohol content to minimize their vulnerability and providing free condoms.20 However, managers may also be a source of exploitation, affecting women’s control over their work by interfering with condom use negotiations, price, and client selection as well as extorting money.21 In some bars or entertainment venues, regulation of the sex work environment may be poor, and expectations of alcohol consumption by both FSWs and clients may compromise their ability to negotiate safety and condom use.20,22 Alternatively, oversight by peers can allow women to refuse risky clients, insist on condoms, and avoid violence.23

FSWs who use or inject drugs may be shunned from entertainment venues and displaced to street settings or less centrally located areas where they are less safe, more likely to be pressured into unprotected sex, and where HIV and harm reduction resources are scarce.17,23 FSWs who conduct sex work in public places (eg, on the street, in cars) are more likely to experience difficulties negotiating condom use and have greater exposure to violence, police harassment, and arrest, which collectively increase HIV vulnerability19 and the possibility of imprisonment. Injecting on the street, in shooting galleries, or other unsafe public places is also associated with increased needle sharing.17,23 Communities with high levels of in-migration and those close to major transport routes are often settings with more FSWs, drugs, and higher HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence.23 Furthermore, changes in local drug markets can shape both sex work and drug use patterns. Studies in the United States and Canada suggest that the spread of crack lowered the price of sexual services and increased HIV risk behaviors.24,25 These factors mediate HIV vulnerability by reducing FSWs’ access to condoms, sterile injection equipment, HIV prevention and treatment, and exposing them to potential harassment by law enforcement (Fig. 1). In this special issue, Blankenship et al26 discuss structural intervention strategies that alter the physical risk environment, which may reduce women’s vulnerability to HIV infection, such as the provision of child care at harm reduction programs and women-only drug treatment programs.

Social Influences

FSWs’ vulnerability to HIV can be positively or negatively influenced by actors in their social sphere, including clients, police, managers, other FSWs, intimate partners, and children. FSWs’ ability to refuse unprotected sex is lower with regular clients, on whom they are more dependent for ongoing financial support, than with casual clients.27 GBV perpetrated by clients, police, managers, and male partners can also reduce women’s condom-negotiating power, increasing HIV risk.28 Furthermore, HIV risk and exposure to violence may be shaped by whether sex workers work for a pimp or other manager and the nature of this relationship, including whether the manager is an intimate or sexual partner, their involvement in women’s drug use, and their level of control over the woman and her work.29 For women who are drug dependent or inebriated, self-efficacy for negotiating condom use or safer injection may be compromised and drug withdrawal may lead FSWs to acquiesce to clients’ demands for unprotected sex.30

Stigma is a pervasive influence on FSWs’ HIV risk behaviors, due in part to the illegality of sex work.17 Some forms of substance use—such as injection drug use—are also highly stigmatized, which relegates FSWs who inject drugs to the margins of both communities where they are socially isolated, more prone to violence, and earn less money.17,23 In countries in which drug or alcohol use among women is a cultural taboo, FSWs may feel pressured to hide their substance use, which may discourage women from accessing services.31 Underlying these stigmas, the social organization of gender and power promotes gender inequalities and norms supporting GBV, which may heighten FSWs’ vulnerability to HIV/STIs.32

One of the most promising social factors associated with lowering vulnerability to HIV/STIs among FSWs is community-driven empowerment through the formal and informal organization of FSWs to support their rights, provide education, and protect FSWs from violence.17,33 FSWs’ intimate partners should also be included in prevention programing, which could be offered individually or as a couple.34 Because most FSWs have children who are major influences on their lives, consideration should be made for how to integrate their reproductive health and family needs with HIV prevention and enhance FSWs’ parenting skills so that their children are not apprehended by authorities.31,35

Economic Influences

Poor socioeconomic conditions often underlie women’s entry into sex work,28 but also increase work-related HIV risks.28 Economic vulnerability, including debt, is associated with reduced negotiating power with clients, resulting in increased unprotected sex and GBV, which are both HIV risk factors.28,36 High proportions (eg, 20%–26%) of FSWs report acquiescing to unprotected sex in exchange for clients’ offer of more money,28,36 further underscoring the role of economic burden as a critical issue affecting FSWs’ vulnerability to HIV. Although more work is needed to identify the precise economic factors underlying women’s entry into sex work, as well as factors that contribute to FSWs’ overall economic vulnerability (eg, need to financially support children or other household members, police bribery to avoid arrest, drug-related or venue-based debt), preliminary studies suggest that economic promotion initiatives among FSWs can reduce HIV risk.37 Such initiatives may include business training or microfinance programs, debt reduction programs, savings or asset building, and financial planning.

Gender-based inequities in the economic sphere are often the basis for women’s economic reliance on sex work and also shape risk environments among FSWs (Fig. 1). For example, many FSWs report reliance on sex work as a result of dual roles as primary carers for children and sole breadwinners for their household,35 yet report reduced capacity for financial independence because of gender constraints in access to educational or vocational training, banking, and asset planning/management, as well as property ownership. Gender-inequitable norms promote GBV among FSWs, reduce power in sexual negotiations with male clients, and sanction illegitimate interactions with male-dominated police forces (eg, requesting bribes, sexual services, or violence); altogether, these influences increase vulnerability to HIV among FSWs.28,38 Thus, economic promotion programing is needed that considers the intersection of gender-based inequities and encompasses a range of social and economic-based challenges across women’s lives. UNAIDS estimates that less than 50% of FSWs worldwide are covered by ongoing HIV prevention programs, which suggests an opportunity for the expansion of programs that integrate the health, social, and economic needs of FSWs.39

Policy/Legal Influences

The legal environment also dictates FSWs’ ability to protect themselves from HIV infection or to access HIV care and treatment (Fig. 1). Sex work is illegal and criminalized in 116 countries. Laws restricting sex work include those that criminalize adult consensual sex and related transactions (buying, soliciting, or procuring), brothel keeping, and management of sex work. Vagrancy, loitering, and public nuisance laws are also used to target sex workers or clients. These laws often force sex work underground, increasing FSWs’ vulnerability to violence and other work-related risks for HIV.17 In some regions (eg, Australia), HIV-positive sex workers are not only criminalized for sex work, they are also subject to disclosure laws in some states and territories, which could deter them from seeking HIV prevention and treatment.

Women who are sex workers and use illicit drugs are doubly marginalized: they are victims of frequent harassment from police, clients, and abusive partners (who are usually also substance users), and they are frequently imprisoned.31 Policing often displaces FSWs to remote venues to avoid police interaction, creating distance from harm reduction services and less protection for FSWs against violence from pimps, managers, clients, and others in the context of sex work.40 Police practices such as workplace raids, arrest and threats of arrest, confiscation of condoms, forcing FSWs to pay bribes or provide sexual favors to avoid arrest are associated with decreased condom use with clients and increased violence.38,41 Monetary bribes and arrests deplete women’s earnings, which can create an urgency to compensate by taking on more clients or agreeing to riskier clients.28

To remove these barriers to HIV prevention and treatment, legislative reforms that are reinforced by police education programs are needed,42 such as those supported by the Law Enforcement and HIV Network (http://www.leahn.org/). A recent modeling scenario in 3 cities (Vancouver, Canada, Bellary, India, and Mombasa, Kenya) found that full decriminalization of sex work could reduce HIV incidence among FSWs and clients by up to 43%.17

HIV RISK ENVIRONMENTS FOR FEMALE PRISONERS

Physical Influences

The physical setting of correctional institutions that house female inmates plays a crucial role in determining their HIV risk. In the contained environment of prisons, women are especially susceptible to sexual abuse by both male staff and male prisoners. Because most countries have fewer numbers of female inmates relative to men, female prisoners may be held in small facilities adjacent to, or within, prisons for men. Often, female inmates are supervised by male guards who may abuse their power. These conditions foster a susceptibility to sexual exploitation, in which some women engage in sex in exchange for goods such as food, drugs, cigarettes, and even toiletries.43 In one US study, 22% of female inmates reported being subjected to prisoner-on-prisoner sexual victimization (most often abusive sexual contact such as inappropriate touching) in the last 6 months.44 At least 1 type of staff-on-prisoner sexual victimization was reported by 8% of female inmates.44 As Gilbert et al report in this special issue, sexual abuse and victimization increase both unprotected sex and needle sharing,32 thereby elevating women’s vulnerability to HIV infection. Transgender women (ie, persons born as male but who identify as female) are held in male prisons and are often the target of serious sexual assault. Policies on the allocation of housing these inmates need revising urgently. Prison administrators can reduce sexual violence by ensuring proper classification of vulnerable inmates so that they are separated from sexual predators, by establishing a reporting mechanism for offenses and by employing female guards.

The main risk for HIV infection that women in prison face is from the shared use of injecting and tattooing equipment,45 both of which are prohibited in most prisons; possession is punished in virtually every country. Women who inject drugs are forced to share syringes with many other individuals because sterile injecting (and tattooing) equipment is unavailable in the majority of prison systems.

Social Influences

The social structure in a prison can provide basic needs (eg, food and shelter) and a routinized schedule. For many women, meeting these needs was a challenge before they entered prison. But with fewer prisons for women than men, women tend to be imprisoned farther from their home and family, which makes visitation by their partners and families less likely than for incarcerated men. Two thirds of women incarcerated in US state prisons are mothers of children under 18 years, 70% of whom had custody of their dependent children before incarceration, and 6% are pregnant when they enter prison.46 In almost all cases, female prisoners are abruptly separated from their infant after giving birth.46 Separation from families increases isolation and is a source of anxiety and depression, which can lead to increased substance use.28,47 Alternatives to incarceration for these mothers need to be explored so that they can reside with their infant while incarcerated, or preferably in the community.

Women, like men, may initiate drug use and injecting in prison. However, the prevalence of substance use disorders in female prisons is almost twice that in the male prisons.48 Women who are more vulnerable to HIV infection because of their past involvement in sex work and/or drug use are also more vulnerable to arrest and imprisonment (Fig. 1). Those with co-occurring mental health disorders may be especially at risk.49 Within prison settings, women’s usual social support networks are disrupted or absent, which can lead women to resist HIV testing or be discouraged from seeking HIV care and treatment. This is compounded by stigma and discrimination against HIV-positive women in prisons, which may further increase vulnerability. Once released, the stigma of having been imprisoned weighs heavily on women; in some settings, women are discriminated against by both family and law enforcement and feel unable to return to their communities.

Economic Influences

Economic factors are an important aspect in determining whether women are imprisoned or not because those who are poor and uneducated are more likely to be arrested and less likely to afford legal counsel. In the United States, the majority of women in prisons (53%) and jails (74%) were unemployed before incarceration.46 Once incarcerated, these women are less likely to be able to afford extra food, toiletries, or legal aid. In the United States, women prisoners are disproportionately women of color, with African American women comprising 46%, white women comprising 36%, and Hispanic women comprising 14% of the prison population nationwide.46

Few countries provide the type and coverage of HIV programs in prison that they provide in the community. Limited funding for HIV prevention and treatment, harm reduction in prisons, and the lack of funding for appropriate training of correctional staff are important economic barriers.50 One study found that sterile syringes in prison cost up to $100 on the black market,24 which significantly increases the likelihood of syringe sharing among women who inject drugs, increasing the risk of HIV infection. Most women in prison are denied evidence-based drug treatment that would reduce their demand for drugs. Recent studies in Australia found that when Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Dependence (MATOD) was provided in prison or after release, it significantly reduced mortality51,52 and recidivism,53 suggesting that expansion of MATOD to those under community supervision would be extremely cost-effective.

Comprehensive coverage of a range of harm reduction measures is essential in the prison settings if HIV is to be prevented. Such measures include needle and syringe programs (NSPs), MATOD, and ART,54 but could also integrate vocational training, financial skills, and asset planning/management.

Policy/Legal Influences

Imprisonment compounds the HIV risk for women in several ways (Fig. 1). Judicial corporal punishment for drug and alcohol offenses exists in 12 countries despite being a violation of international law, and only 30 countries have reformed their drug policies to permit some form of depenalization.42 In many jurisdictions, a larger proportion of women than men are in prison for drug-related offenses.4 In a systematic review of 62 studies, 30%–60% of females used illicit drugs in the month before entering prison, compared with 10%–48% of males.48 This leads to a higher HIV prevalence among female prisoners, greater numbers of women who inject drugs, and comparably fewer HIV prevention services than found in male prisons. In the United States, punitive policies may continue after release, such as denying public housing and food stamps to those with drug felony convictions.

Prison may be a setting in which women start drug use, switch from using one substance to another, or begin a more harmful pattern of drug use.18 Because the half-life of cannabis in urine is weeks, whereas that of heroin is days, some inmates may switch from smoking cannabis to injecting heroin to avoid detection from mandatory urinalysis that inevitably leads to further punishment, including more time in prison.55 In the absence of sterile injecting equipment, women will inject with used needles or with home-made syringes.56 The risk of acquiring HIV for women who inject drugs in prison is greater than that of male prisoners who inject drugs because HIV prevalence is higher among female prison populations.57

As of 2014, few countries provided ART (59 countries), MATOD (41 countries), prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (31 countries), or operated NSPs in prison,57 demonstrating a missed opportunity for prevention and treatment. Instead, the contained environment of correctional settings should serve as a place where HIV, viral hepatitis, STIs, and drug or alcohol dependence are diagnosed and treated. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission should be incorporated into women’s health programs in prison and aligned with national guidelines.

Relative to men, incarceration has a disproportionate effect on women’s adherence to HIV care and treatment that persists after release. A US study found that women released from prison are significantly less likely than men to receive an ART prescription, adhere to an ART regimen, be retained in HIV care and to maintain viral suppression.3 Although ART is available in some prison settings, female prisoners tend to serve shorter sentences than do males, which interrupts their treatment and compromises viral suppression.3 Additional efforts are needed to ensure confidentiality for HIV testing, care, and ART provision to reduce gender disparities in morbidity and mortality for inmates and those under community supervision.

IMPLICATIONS FOR STRUCTURAL LEVEL HIV PREVENTION AND TREATMENT AMONG FSWs AND WOMEN IN PRISON

The physical, social, economic, and policy influences we discuss above overlap to some extent because repeated cycles of detention, incarceration, and release can be physically, socially, and economically destabilizing for women, exacerbating their HIV risk. There is ample evidence that criminalization and enforcement-based approaches toward sex work and drug use increase one’s risk of HIV infection40 and that imprisonment compounds these risks.55 This dynamic interplay requires a multisectoral approach to HIV prevention and treatment that appreciates and respects that not all women want to stop sex work or drug use. Increasingly, advocates, researchers, and policy-makers have called for the repeal of laws that criminalize sex work.17,58,59 Research is needed to evaluate models of sex work regulation and decriminalization to inform national policies, taking advantage of natural experiments in which legislative changes have been enacted (eg, New Zealand, Canada, Germany, and Australia).

Although female prisoners are much more likely than male prisoners to have a drug problem, they are much less likely than men to have access to drug treatment in prison. For example, in Iran, methadone maintenance was available in men’s prisons long before it was available in women’s prisons. At a minimum, full access to free evidence-based drug and alcohol treatment should be offered to all women who need it, both inside and outside prison. Alternatives to incarceration for drug-involved women are also needed. Because most women are in prison for nonviolent offenses and pose no risk to the public, we call on all governments to grant amnesty to women imprisoned on drug possession offenses. Serious attention should be paid to development and implementation of noncustodial sentences for women, particularly during pregnancy and when they have young children.

Given the complex HIV/STI prevention needs of drug-involved FSWs and incarcerated women, a broad set of gender-specific HIV/STI prevention tools for this population need to be identified, developed, and implemented, as Figure 1 suggests. Although some interventions for FSWs who are drug or alcohol dependent have been developed,60,61 there are few evidence-based HIV/STI prevention interventions for incarcerated women or those under community supervision. An example is Project POWER, which is a behavioral intervention aimed to reduce risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV and STIs among incarcerated women returning to their communities.62 POWER was adapted based on formative research with prison staff and administration, incarcerated and previously incarcerated women, and community advisory boards. A randomized trial using this adaptation with 521 women in 2 North Carolina correctional facilities showed that POWER participants had significantly less occasions of unprotected sex with both main and casual male partners. POWER participants also reported significantly fewer barriers to using condoms and greater HIV knowledge, health-protective communication, and tangible social support. However, the intervention had no significant effects on incident STIs.63

Because of the high rates of serious mental illness along with substance use disorders in incarcerated women49 who rarely receive treatment for these conditions, there is a need for targeted attention to the chronic medical, psychiatric, and drug treatment needs of women at risk for incarceration, in jail and after release. Lessons can be learned from a successful pilot project treating major depressive disorders in prison settings conducted in Rhode Island, USA, where of the 25 study participants, 72% were free of all depressive disorders after treatment.64

Existing prison facilities, programs, and services for women inmates have all been developed initially for men, who account for the larger proportion of prison populations. Women prisoners present specific challenges for correctional authorities despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that they constitute a very small proportion of prison populations. Their profile and background and the reasons for which they are imprisoned differ from those of incarcerated men. Once in prison, women’s psychological, social, and health care needs are also different. It follows that all facets of prison facilities, programs, and services must be tailored to meet the particular needs of women offenders.

CONCLUSIONS

In this article, we highlighted the physical, social, economic, and policy environments that contribute to HIV risk among FSWs and female prisoners, noting important intersections and unique aspects that influence risk for these 2 populations (Fig. 1). Although the physical environment for FSWs and female prisoners may look different, the controlled environment of prisons and FSW venues represents a missed opportunity for the provision of HIV prevention and treatment as well as drug treatment services. These physical spaces may provide an opportunity to deliver key services, including HIV testing, ART, MATOD, NSP, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and interventions to promote linkages to care and adherence. Similarly, although the social organization of FSWs compared with that of women in prisons may differ, the social structure of gender and power often underlies women’s involvement in sex work and is a major contributing factor to HIV risk among both FSWs and female prisoners (eg, affecting condom use in sex trades, experiences of violence, and access to sterile syringes). Community mobilization of FSWs has shown promise for improving health and well-being and could also be beneficial within prison and community supervision settings to increase womens’ collective power to advocate for improved access to treatment and prevention for HIV and substance use. Economic vulnerability is also an antecedent to both sex work and imprisonment; yet, there is a dearth of programs that integrate HIV prevention and treatment with the economic needs of FSWs or women recently released from prison. This is an important avenue for future research. Furthermore, both sex work and drug-related policies work in tandem to increase the size of the incarcerated female population but also exacerbate vulnerabilities to HIV by increasing stigma, disrupting social support structures, and obstructing the provision of key HIV services.

In summary, the literature on HIV prevention among FSWs and female prisoners highlights the unique risk environments of these 2 populations, but also the ways these risks intersect. It is in this intersection that we propose as key opportunities for improved HIV prevention and care. Women who engage in sex work, use drugs, or are imprisoned come from all communities and deserve sustained access to HIV prevention and treatment for substance use and HIV, helping them and their families to lead healthy and satisfying lives.

Acknowledgments

S.A.S. is supported by an NIDA MERIT award R37 DA019829. B.S.W. is supported by T32DA023356. E.R. is supported by K01MH099969 and R03 DA035699. T.A. is supported by ICDDR,B, which receives unrestricted funds from its core donors which include: Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), and the Department for International Development, United Kingdom (DFID). K.D. is supported by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ward H, Aral SO. Globalisation, the sex industry, and health. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:345–347. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walmsley R. World Female Imprisonment List. 2. London, United Kingdom: International Centre for Prison Studies; 2012. Women and girls in penal institutions, including pre-trial detainees/remand prisoners. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer JP, Zelenev A, Wickersham JA, et al. Gender disparities in HIV treatment outcomes following release from jail: results from a multicenter study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:434–441. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101:181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iakobishvili E. Cause for Alarm: The Incarceration of Women for Drug offences in Europe and Central Asia, and the need for legislative and Sentencing reform. International Harm Reduction Association; London UK: Harm Reduction International; 2012. pp. 23–27. Available at: http://www.ihra.net/files/2012/03/11/HRI_WomenInPrisonReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacomello C. Women, drug offenses and penitentiary systems in Latin America. Paper presented at: International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC); October 2013; London, United Kingdom. [Accessed April 12, 2015]. This is a briefing paper: Available at: http://idpc.net/publications/2013/11/idpc-briefing-paper-women-drug-offenses-and-penitentiary-systems-in-latin-america. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan K. HIV prevalence in prison: a global overview. Paper presented at: The 20th International AIDS Conference; July 20–25, 2014; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNODC. [Accessed February 18, 2015];A rapid situation assessment of HIV/STI/TB and drug abuse among prisoners in Uganda prisons service. 2009 Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/publications/RSA_Report.pdf.

- 10.Kupe N. [Accessed February 18, 2015];Sexual health and HIV knowledge, practice and prevalence among male inmates in Kenya. 2011 Available at: http://www.aidsportal.org/web/guest/resource?id=dad7da0d-8220-4bb1-a57e-159f48babf31#sthash.iEkMHDkJ.dpuf.

- 11.Nelwan EJ, Van Crevel R, Alisjahbana B, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C in an Indonesian prison: prevalence, risk factors and implications of HIV screening. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:1491–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lomidze G, Tsereteli N, Kasrelishvili V, et al. Prevalence of HIV in Georgian prisons: results of randomized research. Paper presented at: XVIII International AIDS Conference; July 18–23, 2010; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams LM, Kendall S, Smith A, et al. HIV risk behaviors of male and female jail inmates prior to incarceration and one year post-release. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2685–2694. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9990-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gough E, Kempf MC, Graham L, et al. HIV and hepatitis B and C incidence rates in US correctional populations and high risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:777. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Underhill K, Dumont D, Operario D. HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement: a systematic review of HIV risk-reduction interventions in incarceration and community settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e27–e53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaze L, Bonczar T. Probation and Parole in the United States, 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385:55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin RE, Gold F, Murphy W, et al. Drug use and risk of bloodborne infections: a survey of female prisoners in British Columbia. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF03403669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maher L, Mooney-Somers J, Phlong P, et al. Selling sex in unsafe spaces: sex work risk environments in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urada LA, Morisky DE, Hernandez LI, et al. Social and structural factors associated with consistent condom use among female entertainment workers trading sex in the Philippines. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:523–535. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng SS, Mak WW. Contextual influences on safer sex negotiation among female sex workers (FSWs) in Hong Kong: the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), FSWs’ managers, and clients. AIDS Care. 2010;22:606–613. doi: 10.1080/09540120903311441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldenberg SM, Strathdee SA, Gallardo M, et al. How important are venue-based HIV risks among male clients of female sex workers? A mixed methods analysis of the risk environment in nightlife venues in Tijuana, Mexico. Health Place. 2011;17:748–756. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, et al. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourgois P, Dunlap E. Exorcising sex-for-crack: an ethnographic perspective from Harlem. Crack pipe as pimp: an ethnographic investigation of sex-for-crack exchanges. 1993:97–132. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J. Gender and power on the streets: street prostitution in the era of crack cocaine. J Contemp Ethnog. 1995;23:427–452. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG. Structural interventions for HIV prevention among women who use or inject drugs: a global perspective. JAIDS. 2015;69(suppl 2):S140–S145. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson AM, Syvertsen JL, Amaro H, et al. Can’t buy my love: a typology of female sex workers’ commercial relationships in the Mexico–US border region. J Sex Res. 2014;51:711–720. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.757283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, et al. The context of economic insecurity and its relation to violence and risk factors for HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(suppl 4):81–89. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, et al. Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:278–283. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G, et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers who inject drugs in the Mexico-US border region. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.003. Pii: S0955–3959(14)00285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, et al. Targeting the SAVA (substance abuse, violence and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: a global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. JAIDS. 2015;69(suppl 2):S118–S127. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerrigan D, Kennedy CE, Morgan-Thomas R, et al. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet. 2015;385:172–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60973-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palinkas LA, Robertson AM, Syvertsen JL, et al. Client perspectives on design and implementation of a couples-based intervention to reduce sexual and drug risk behaviors among female sex workers and their noncommercial partners in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0715-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rolon M, Syvertsen J, Robertson A, et al. The influence of having children on HIV-related risk behaviors of female sex workers and their intimate male partners in two Mexico-US border cities. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59:214–219. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmt009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ntumbanzondo M, Dubrow R, Niccolai LM, et al. Unprotected intercourse for extra money among commercial sex workers in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care. 2006;18:777–785. doi: 10.1080/09540120500412824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman SG, German D, Cheng Y, et al. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erausquin JT, Reed E, Blankenship KM. Police-related experiences and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 5):S1223–S1228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010. UNAIDS; 2010. [Accessed April 12, 2015]. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, et al. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:659–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erausquin JT, Reed E, Blankenship KM. Change over time in police interactions and HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0926-5. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25354735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Strathdee SA, Beletsky L, Kerr T. HIV, drugs and the legal environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(suppl 1):S27–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.001. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25265900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plugge E, Douglas NF, Fitzpatrick R. The Health of Women in Prison; Study Findings. Department of Public Health, University of Oxford; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolff N, Blitz CL, Shi J. Rates of sexual victimization in prison for inmates with and without mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1087–1094. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.8.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolan K, Wodak A, Hall W, et al. HIV risk behaviour of IDUs before, during and after imprisonment in New South Wales. Addict Res Theory. 1996;4:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Committee to End the Marion Lockdown (CEML), US Incarcer Nation. Walking Steel. Women in Prison. Chicago, IL: Newsletter Fall, CEML; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, et al. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and implications for post-release HIV transmission. J Urban Health. 2011;88:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 2002;359:545–550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binswanger IA, Merrill JO, Krueger PM, et al. Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:476–482. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Degenhardt L, Larney S, Kimber J, et al. The impact of opioid substitution therapy on mortality post-release from prison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;146:e260. doi: 10.1111/add.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larney S, Gisev N, Farrell M, et al. Opioid substitution therapy as a strategy to reduce deaths in prison: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004666. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larney S, Toson B, Burns L, et al. Effect of prison-based opioid substitution treatment and post-release retention in treatment on risk of re-incarceration. Addiction. 2012;107:372–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.UNODC. HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care in Prisons and Other Closed Settings: A Comprehensive Package of Interventions. Vienna, Austria: United Office on Drugs and Crime; 2013. [Accessed April 12, 2015]. Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/HIV_comprehensive_package_prison_2013_eBook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boys A, Farrell M, Bebbington P, et al. Drug use and initiation in prison: results from a national prison survey in England and Wales. Addiction. 2002;97:1551–1560. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolan K, Larney S, Jacka B, et al. Presence of hepatitis C virus in syringes confiscated in prisons in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1655–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dolan K. HIV services in prison: a global systematic review. Paper presented at: The 20th International AIDS Conference, Poster presentation; July 20–25, 2014; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Decker MR, Crago A-L, Chu SKH, et al. Human rights violations against sex workers: burden and effect on HIV. Lancet. 2015;385:186–199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeffreys E, Matthews K, Thomas A. HIV criminalisation and sex work in Australia. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:129–136. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)35496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strathdee SA, Abramovitz D, Lozada R, et al. Reductions in HIV/STI incidence and sharing of injection equipment among female sex workers who inject drugs: results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wechsberg WM, Zule WA, Luseno WK, et al. Effectiveness of an adapted evidence-based woman-focused intervention for sex workers and non-sex workers: the women’s health CoOp in South Africa. J Drug Issues. 2011;41:233–252. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fasula AM, Fogel CI, Gelaude D, et al. Project power: Adapting an evidence-based HIV/STI prevention intervention for incarcerated women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25:203–215. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fogel CI, Crandell JL, Neevel A, et al. Efficacy of an adapted HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention intervention for incarcerated women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):802–809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302105. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson JE, Zlotnick C. Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]