Abstract

We examined whether changes in different forms of social participation were associated with changes in depressive symptoms in older Europeans. We used lagged individual fixed-effects models based on data from 9,068 persons aged ≥50 years in wave 1 (2004/2005), wave 2 (2006/2007), and wave 4 (2010/2011) of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). After we controlled for a wide set of confounders, increased participation in religious organizations predicted a decline in depressive symptoms (EURO-D Scale; possible range, 0–12) 4 years later (β = −0.190 units, 95% confidence interval: −0.365, −0.016), while participation in political/community organizations was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (β = 0.222 units, 95% confidence interval: 0.018, 0.428). There were no significant differences between European regions in these associations. Our findings suggest that social participation is associated with depressive symptoms, but the direction and strength of the association depend on the type of social activity. Participation in religious organizations may offer mental health benefits beyond those offered by other forms of social participation.

Keywords: aging, depression, Europe, fixed-effects models, social participation

The recent Global Burden of Disease Study ranked major depressive disorders as a leading cause of disability (1, 2). In a study comparing 10 countries in Northern, Southern, and Western Europe, Castro-Costa et al. (3) reported that the prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms in older adults ranged from 18% in Denmark to 37% in Spain. Despite the high burden of depression in old age, there is limited understanding of its potential causes and of interventions that may help in preventing depression among older persons.

Lower social participation and less social interaction in old age are each associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (4–15). Social interaction provides people with a sense of belonging and social identity, together with opportunities for participation in activities and projects (16). With some exceptions (17), several studies have found that active participation in religious or church activities, clubs, and political groups and volunteering are associated with better mental health and reduced levels of depressive symptoms (6, 8, 11, 13–15). However, the causal impact of social participation on depression has not been well established. Associations may reflect confounding by unmeasured characteristics or reverse causality from depression to social participation. One source of confounding comes from permanent personal characteristics that differ between individuals and that may be associated with both depressive symptoms and social participation, such as personality traits, socioeconomic status, childhood conditions, or intellectual ability (18). For example, persons with certain psychological or personality traits may be more likely to engage in social participation and may also exhibit lower levels of depression, which could result in a spurious association between social participation and depression.

Fixed-effects models have been advocated as a useful approach for controlling for the impact of these permanent characteristics (19–22). Fixed-effects estimators, sometimes called “within-person” estimators, control for unobserved individual heterogeneity that may be correlated with the explanatory variable. They exploit the longitudinal nature of the data by assessing the association between changes in the explanatory variable and changes in the outcome variable within individuals, thus controlling for permanent characteristics that vary across individuals. This is in contrast to the more commonly applied random-effects or “between-person” estimators, which combine variation between individuals as well as within individuals for estimation. While confounding by unmeasured time-varying characteristics is also a potential concern in fixed-effects models, they can provide additional insights into the potential causal association between social participation and depression by controlling for individual heterogeneity.

Earlier studies linking social participation to depressive symptoms focused primarily on single populations or countries (5, 6, 13, 23–25). Levels of both depressive symptoms and social participation vary considerably across countries, possibly due to cross-national variations in the availability of state-provided support and services, family and social structures, or policies that promote or discourage social participation and mental well-being (3, 26, 27). A potential hypothesis is that the social significance of different forms of social participation is context-dependent, such that the mental health benefits of social participation vary across countries or regions. For example, in Southern European countries with stronger family networks, voluntary work may be less relevant to health than in Northern European countries, where family support roles have been replaced by formal care and the social benefits of voluntary work may be larger (28).

Building upon earlier research (29), we examined how changes in different forms of social participation predict changes in levels of depressive symptoms in older persons using fixed-effects models. In addition, we explored whether the association between various forms of social participation and depressive symptoms differs across regions of Europe.

METHODS

Study design

Data for this study were drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (30). In SHARE, information on health, social networks, and economic factors was collected from adults aged 50 years or older using computer-assisted personal interviews. During the first wave of the study (2004/2005), 31,115 participants from 12 countries were included. The total household response rate was 62%, varying from 38.8% in Switzerland to 81.0% in France. We included respondents who entered SHARE during wave 1 (2004/2005) and were followed up in wave 2 (2006/2007) and wave 4 (2010/2011) (n = 10,706). Data from wave 3 (2008/2009) were excluded, because depressive symptoms were not assessed in wave 3. Ten countries contributed to all 3 waves of the longitudinal sample: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands.

Social participation

In each wave of SHARE, respondents were asked whether they had engaged in the following activities during the last month: 1) voluntary or charity work; 2) educational or training courses; 3) sports, social clubs, or other kinds of club activities; 4) participation in religious organizations; and 5) participation in political or community organizations. For each activity, an additional question was asked about the frequency of participation, using 4 response options: “almost daily,” “almost every week,” “almost every month,” and “less often.” In wave 4, the recall period for participation in social activities was altered to refer to the last 12 months. To maintain consistency in the recall period, our analysis focused on changes in social participation between waves 1 and 2 only.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed in all 3 waves of the study and were measured by means of the EURO-D Scale (31). The EURO-D consists of 12 items: depression, pessimism, death wishes, guilt, sleep, interest, irritability, appetite, fatigue, concentration, enjoyment, and tearfulness. Each item is scored 0 (symptom not present) or 1 (symptom present), and item scores are summed (0–12). Previous studies have demonstrated the validity of this measure against a variety of criteria for clinically significant depression, with an optimal cutoff point of 4 or above (31, 32).

Background variables

Educational level was based on the highest educational degree obtained. National levels were reclassified according to the 1997 International Standard Classification of Education into 3 categories: lower education (classifications 0–2), medium education (classifications 3–4), and higher education (classifications 5–6) (33). Countries were classified into 3 geographical regions: Northern Europe (Sweden and Denmark), Southern Europe (Italy and Spain), and Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands). Marital status was defined as 1) married; 2) divorced, separated or unmarried; or 3) widowed. Household size was categorized as 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 persons. Concerning employment status, respondents were classified as either 1) employed, including self-employment; 2) unemployed, including permanently sick or disabled persons and homemakers; or 3) retired. The variable “financial difficulties,” which measured the extent to which respondents were able to make ends meet on their income, included 4 response options ranging from “with great difficulty” to “easily.” Self-rated health was measured using a 5-point scale with 5 response options: “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” and “poor.” Long-term illness was assessed as a self-reported long-term health problem, illness, disability, or infirmity. Respondents' levels of functioning and disability were assessed by means of the Global Activity Limitation Index, Activities of Daily Living, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (34, 35). Scores for each index of activity limitations were dichotomized on the basis of whether respondents had limitations in performing 1 or more activities. The presence of a physician-diagnosed disease was assessed for heart attack, high blood pressure or hypertension, stroke, diabetes or high blood sugar, and chronic lung disease.

Statistical analysis

We applied fixed-effects models (19–21) to assess whether within-person changes in social participation were associated with within-person changes in depressive symptoms. Fixed effects control for potential time-invariant confounders that vary across individuals, such as sex, family background, preexisting health, and levels of depression. In essence, fixed-effects models use each individual as his or her own control, by comparing an individual's depression score when exposed to a given level of social participation with that same individual's depression score when he or she is exposed to a different level of social participation. Assuming that intraindividual changes in exposure are uncorrelated with changes in other variables, the difference in depression scores between these 2 periods is an estimate of the association between social participation and depressive symptoms for that individual. Averaging these differences across all persons in the sample yields an estimate of the “average treatment effect,” which controls for all stable individual characteristics. Although it does not control for time-varying factors such as employment and marital status, these variables can be handled conventionally by incorporating them into the regression model. Fixed-effect models have 2 requirements. First, the dependent variable must be measured for each individual in a comparable fashion using a similar metric at 2 or more points in time. Second, the exposure variable of interest must change across these 2 occasions for at least a fraction of the sample (36).

Specification of our basic model was as follows:

| (1) |

where EURO-Dit indicates EURO-D score for individual i at time t, social participationit is a vector of indicator variables for social participation, xit is a vector of supplementary control regressors, and ϵit is the error term. μt accounts for time effects that are constant across individuals, while ∝i controls for time-invariant individual characteristics.

To minimize the potential impact of reverse causality, we implemented fixed-effects models that used lagged (by 4 years) social participation and examined whether changes in social participation indicators between waves 1 and 2 were associated with changes in depressive symptoms between waves 2 and 4. In the Web material, we also show results from contemporaneous models that examined the association between changes in social participation between waves 1 and 2 and changes in depressive symptoms during the same period (see Web Table 1 and Web Figure 1, available at http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/).

In addition to the fixed-effects models, we implemented a series of random-effects models. We followed standard approaches and conducted a Hausman specification test (37), which tests the null hypothesis that estimates from the fixed-effects model are not different from estimates from the random-effects model. Our results yielded a significant Hausman test result (P < 0.0001), which indicated that at conventional levels of significance, the assumption of no correlation between explanatory variables and individual characteristics was violated in the random-effects model. We report estimates from random-effects models in Web Table 2.

To calculate population-descriptive statistics, we used appropriate weights to account for the sampling design, nonresponse, and attrition. Weights were calibrated against the national population by age group and sex, as well as for mortality between waves. The analytical sample was limited to respondents with valid weights for the balanced panel (n = 9,491). Respondents were dropped if information was missing for depressive symptoms at wave 2 or 4 (n = 363) or for social participation at wave 1 or 2 (n = 132); this resulted in an analytical sample of 9,068 persons.

We followed a stepwise approach in the construction of the fixed-effects models, starting with a basic model that controlled for age and time (wave) only. Models additionally incorporated controls for time-varying marital status, household size, employment status, financial difficulties, self-rated health, long-term illness, activity limitations, and self-reports of major disease diagnoses (heart attack, high blood pressure/hypertension, stroke, diabetes/high blood sugar, and chronic lung disease). We did not apply weights in regression models, because when sampling probabilities vary only on the basis of explanatory variables, weighting is unnecessary for consistency and potentially harmful for precision (38). Nonetheless, we report estimates from weighted regression analyses in Web Table 3. Because of the low efficiency in the fixed-effects models, estimates from weighted models were very imprecise; therefore, we decided to emphasize unweighted results. We applied robust standard errors to account for nonindependence clustering at the individual level. All analyses were carried out using Stata statistical software, release 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The mean age at baseline was 63 years (Table 1). Fewer than half of respondents were male (44.9%), and about half had a lower level of education (50.6%). Educational attainment varied across European regions; the highest share of persons with lower education lived in Southern Europe (78.6%). Almost half of the study population was retired (48.3%), and 41.1% reported having difficulties making ends meet. Over 50% reported having a long-term illness; a physician's diagnosis of hypertension was the condition reported most often (33.0%), followed by heart attack (10.3%) and diabetes (9.6%).

Table 1.

Weighted General Characteristics of Selected Respondents (Participants in Waves 1, 2, and 4) Aged 50 Years or Older at Baseline, by Geographical Region, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004/2005

| Total (n = 9,068) |

Geographical Region, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Western Europe (n = 5,459) | Northern Europe (n = 1,673) | Southern Europe (n = 1,936) | |

| Age, yearsa | 9,068 | 62.9 (8.8) | 62.9 (8.9) | 62.7 (9.3) | 63.1 (8.7) |

| Male sex | 9,068 | 44.9 | 44.1 | 45.9 | 45.8 |

| Educational level | 8,998 | ||||

| Lower | 50.6 | 32.4 | 34.8 | 78.6 | |

| Medium | 30.8 | 41.1 | 34.0 | 15.6 | |

| Higher | 18.6 | 26.4 | 31.2 | 5.9 | |

| Marital status | 9,067 | ||||

| Married | 70.1 | 68.1 | 64.1 | 73.9 | |

| Divorced, separated, or unmarried | 14.4 | 16.5 | 21.8 | 10.4 | |

| Widowed | 15.5 | 15.5 | 14.1 | 15.7 | |

| Household size (no. of persons) | 9,068 | ||||

| 1 | 21.5 | 24.7 | 30.8 | 15.7 | |

| 2 | 50.9 | 57.1 | 57.6 | 41.0 | |

| 3 | 14.8 | 10.4 | 6.7 | 22.1 | |

| ≥4 | 12.9 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 21.2 | |

| Employment status | 9,068 | ||||

| Employed | 29.1 | 32.4 | 45.3 | 22.2 | |

| Unemployed | 22.6 | 18.5 | 7.1 | 30.5 | |

| Retired | 48.3 | 49.1 | 47.6 | 47.3 | |

| Financial difficulties | 6,460 | 41.1 | 27.0 | 19.8 | 63.6 |

| Less than very good self-rated health | 9,068 | 74.0 | 73.0 | 45.8 | 79.1 |

| Long-term illness | 9,067 | 50.9 | 50.0 | 52.2 | 52.0 |

| Activity limitations | |||||

| GALI | 9,068 | 39.8 | 40.2 | 38.9 | 39.3 |

| ADL | 9,066 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 7.4 |

| IADL | 9,066 | 10.4 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 11.5 |

| Physician-diagnosed disease | 9,065 | ||||

| Heart attack | 10.3 | 11.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | |

| Hypertension | 33.0 | 32.0 | 29.1 | 35.0 | |

| Stroke | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.1 | |

| Diabetes | 9.6 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 10.7 | |

| Lung disease | 5.5 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 6.9 | |

Abbreviations: ADL, Activities of Daily Living; GALI, Global Activity Limitation Index; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

a Expressed as mean (standard deviation).

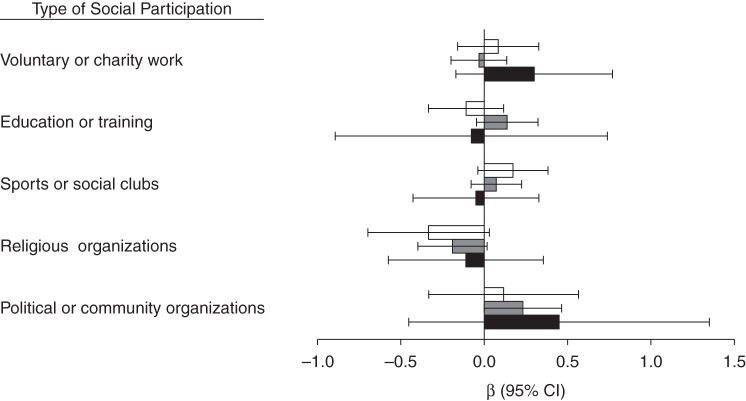

Levels of social participation varied markedly across regions (Table 2). Respondents from the Southern European countries reported the least participation. This difference was most pronounced for participation in sports, social clubs, or other kinds of club activities (7.5% in Southern Europe, 26.5% in Western Europe, 32.6% in Northern Europe). Although the prevalence increased slightly for several measures, social participation was very similar across the 2 waves for all regions and measures. There was great variation in the prevalence of depressive symptoms across regions, as well as over time (Figure 1). In wave 1, 26.0% of the respondents had a depressive symptom score of ≥4 points, the cutoff indicative of clinical depression symptomatology, but levels varied from 15.5% in Northern Europe to 34.6% in Southern Europe. There was a small decline in the prevalence of depressive symptoms between waves 1 and 2, whereas an increase in depressive symptoms was observed between waves 2 and 4. Within types of social participation, the lowest baseline prevalence of depressive symptoms was found for participation in political activities (18.0%) and the highest for participation in religious activities (23.2%) (data not shown). For all types of activities, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was highest among persons who were not active.

Table 2.

Weighted Prevalence (%) of the Frequency of Social Participation Among Selected Respondents (Participants in Waves 1 and 2) Aged 50 Years or Older (n = 9,068)a, by Geographical Region, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004/2005–2006/2007

| Type of Activity and Frequency, times/week | Study Wave and Geographical Region |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 (2004/2005) |

Wave 2 (2006/2007) |

|||||

| Western Europe | Northern Europe | Southern Europe | Western Europe | Northern Europe | Southern Europe | |

| Voluntary/charity work | ||||||

| 0 | 81.6 | 78.0 | 92.9 | 80.7 | 74.5 | 91.8 |

| <1 | 6.3 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 6.9 | 10.0 | 2.4 |

| ≥1 | 12.2 | 12.7 | 4.5 | 12.4 | 15.5 | 5.8 |

| Education/training | ||||||

| 0 | 91.8 | 85.5 | 98.5 | 91.6 | 83.0 | 97.4 |

| <1 | 4.9 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 8.8 | 0.6 |

| ≥1 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 8.2 | 2.0 |

| Sports/social clubs | ||||||

| 0 | 73.5 | 67.4 | 92.5 | 72.1 | 62.8 | 89.9 |

| <1 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 1.9 | 7.2 | 4.8 | 2.0 |

| ≥1 | 18.7 | 25.7 | 5.7 | 20.7 | 32.4 | 8.2 |

| Religious organizations | ||||||

| 0 | 89.3 | 93.7 | 91.4 | 88.4 | 87.8 | 90.3 |

| <1 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 2.1 |

| ≥1 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 7.6 |

| Political/community organizations | ||||||

| 0 | 94.1 | 94.4 | 96.9 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 98.2 |

| <1 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.9 |

| ≥1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.9 |

a Sample size varied by 0–3 missing values, according to the type of activity.

Figure 1.

Weighted estimates of the prevalence (%) of ≥4 depressive symptoms among respondents aged 50 years or older, by geographical region, in waves 1 (n = 9,027), 2 (n = 9,068), and 4 (n = 9,068) of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004–2011. White columns represent wave 1 (2004/2005), gray columns represent wave 2 (2006/2007), and black columns represent wave 4 (2010/2011). T-shaped bars, standard errors.

In models that assessed the contemporaneous association between changes in social participation and depressive symptoms between waves 1 and 2 and controlled for confounders, participation in sports, social clubs, or other kinds of clubs and participation in political or community organizations predicted a decline in depressive symptoms (for sports/social clubs, β = −0.102, 95% confidence interval (CI): −0.186, −0.019; for political/community organizations, β = −0.170, 95% CI: −0.319, −0.022) (Web Table 1 and Web Figure 1). However, many of these associations did not hold in lagged fixed-effects models. As shown in Table 3, only increased participation in religious organizations was associated with a decline in depressive symptoms 4 years later, even after controlling for all confounders (β = −0.190, 95% CI: −0.365, −0.016). In addition, increased participation in political/community organizations was associated with higher depressive symptom scores (β = 0.222, 95% CI: 0.018, 0.428).

Table 3.

Four-Year-Lagged Associations Between Changes in Social Participation and Changes in Depressive Symptom Score Among Selected Respondents (Participants in Waves 1, 2, and 4) Aged 50 Years or Older, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004/2005–2010/2011

| Type of Activity | Model 1a (n = 9,068) |

Model 2b (n = 7,385) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Robust 95% CI | β | Robust 95% CI | |

| Voluntary/charity work | 0.085 | −0.022, 0.193 | 0.020 | −0.112, 0.152 |

| Education/training | 0.023 | −0.096, 0.141 | 0.041 | −0.101, 0.183 |

| Sports/social clubs | 0.097 | 0.004, 0.190 | 0.081 | −0.036, 0.199 |

| Religious organizations | −0.145 | −0.281, −0.010 | −0.190 | −0.365, −0.016 |

| Political/community organizations | 0.111 | −0.051, 0.273 | 0.222 | 0.018, 0.428 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Results were adjusted for social participation (mutually adjusted), age, and time.

b Results were adjusted for social participation (mutually adjusted), age, time, household size, marital status, employment status, financial difficulties, self-rated health, long-term illness, activity limitations, and physician-diagnosed diseases (heart attack, high blood pressure or hypertension, stroke, diabetes or high blood sugar, and chronic lung disease).

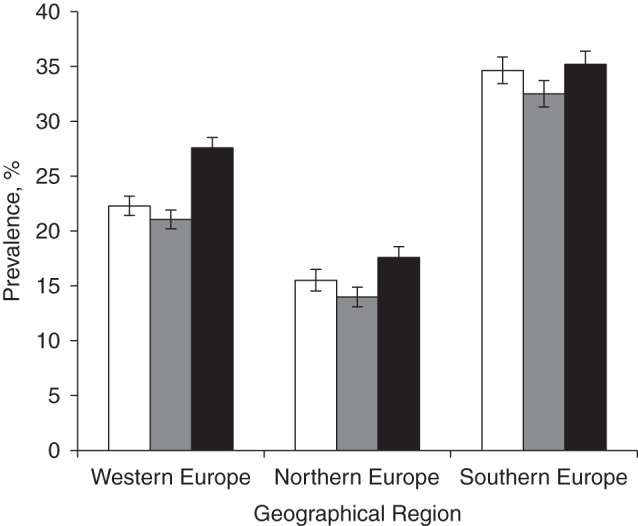

To explore whether there were differences in the association between social participation and depressive symptoms across Europe, we carried out stratified analysis by geographical region (Figure 2). There was no evidence of significant or systematic differences between European regions in these associations, although this was partly due to wide confidence intervals in each region.

Figure 2.

Four-year-lagged associations (β coefficients) between changes in social participation and changes in depressive symptom scores among selected respondents (participants in waves 1, 2, and 4) aged 50 years or older (n = 7,385), by geographical region, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004–2011. White columns represent Northern Europe, gray columns represent Western Europe, and black columns represent Southern Europe. T-shaped bars, robust 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that social participation is associated with levels of depressive symptoms; however, the strength and direction of the association depend on the type of activity. Participation in religious activities was the only form of social engagement associated with a decline in depressive symptoms 4 years later. Participation in a political or community organization was instead associated with an increase in depressive symptoms. Thus, the mechanisms linking social participation to mental health in old age may differ for different activities.

Our results offer mixed support for the previously observed association between social participation and depressive symptoms (5, 6, 11, 13–15, 23–25, 39). We did not find significant associations for participation in voluntary or charity work or participation in educational or training courses. This finding seems to be in contrast with results from previous research (40, 41). In models that adjusted only for age and time, we did find contemporaneous associations between volunteering and depressive symptoms. However, these associations were not robust to control for time-varying confounding, and these activities did not predict changes in depressive symptoms 4 years later. Similarly, changes in participation in sports, social clubs, and other club activities were associated with a contemporaneous decline in depressive symptoms but did not predict changes in depressive symptoms 4 years later. A possible explanation is that short-term benefits arising from these forms of social participation diminish over time or that they reflect the impact of depression on the likelihood of participating in social activities.

Earlier research found that religiously active persons have better mental health than the religiously inactive (24, 42). Our findings suggest that this association might reflect a causal association. Participation in religious organizations may protect mental health through several pathways, including influencing lifestyle, enhancing social support networks, and offering a mechanism for coping with stress (24, 42). For example, religion has been shown to serve as a coping mechanism during a period of illness in late life (43, 44). Through participation in religious activities, people may also become more attached to their communities, which prevents social isolation, a predictor of old-age depression. Spirituality has also been proposed as an important promoter of mental health, but this construct is not well defined, and its relationship with depression is not well understood (24). By contrast, people may not accrue the same social support, lifestyle, and coping benefits from participating in sports, social clubs, or other kinds of clubs, which may explain why these forms of social participation did not predict levels of depressive symptoms 4 years later. Although we expected stronger associations between social participation and depressive symptoms in Northern and Western European countries, the lack of regional differences in the associations across Europe supports the findings of Di Gessa and Grundy (17).

We found that participation in a political or community organization was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms 4 years later. Insights from the effort-reward balance theory may provide a partial explanation. Participation in political or community organizations could be beneficial for health when reciprocity is expected (45), which may partly explain the positive association in contemporaneous models. Respondents may experience a higher sense of reward when starting participation in a political or community organization. In the long run, however, the balance may shift towards higher effort and lower reward, which may trigger depressive symptoms. Another potential explanation for contemporaneous associations is reverse causality—that is, that depressed persons may be less likely to participate in political or community organizations. Lagged models are less susceptible to reverse causality, as they relate current changes in social participation to subsequent changes in depressive symptoms. In our study, however, there was relatively little change in participation in a political or community organization, so fixed effects may not be the best method for assessing the impact of this particular form of social participation.

Some limitations of our study should be considered. Changes in social participation may be correlated with changes in other variables associated with depressive symptoms. For example, older persons may increase or initiate participation in religious activities after the birth of a grandchild, the death of a child or sibling, or the onset of illness. The influence of several of these variables on our estimates is difficult to anticipate, however, as several of them might increase rather than decrease levels of depression, leading to underestimation of the association between participation in religious activities and depression. Another concern is reverse causation. Although we found that participation in a religious organization was associated with decreased depression scores over a 4-year period, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that this association may have been due to the impact of depression on social participation. However, sensitivity analysis that excluded respondents who had 4 or more depressive symptoms at baseline confirmed our finding for participation in religious organizations, diminishing concerns about reverse causation (β = −0.306; 95% CI: −0.481, −0.131). Next, as with other longitudinal studies, SHARE suffered from attrition resulting from both mortality and nonresponse. This may have led to sample selection bias, potentially compromising internal validity (30). Earlier substudies from the SHARE project showed that although health and living arrangements at baseline predicted initial survey participation and panel retention, there were no systematic differences in response and attrition rates according to key characteristics such as sex, age, and employment status (46, 47). While there is no fully satisfactory way to address this, we incorporated these and other time-varying factors into our models and focused our interpretation on these models. Finally, a limitation of fixed-effects models is that estimation is based only on the small fraction of people who change their exposure during the follow-up period. For example, between waves 1 and 2, only 6.8% of the sample changed their participation in political/community organizations, which resulted in large standard errors. Changes were more common for participation in voluntary/charity work (15.0%), education/training (11.9%), sports/social clubs (20.1%), and religious activities (10.6%).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that increased social participation is associated with depressive symptoms. However, the strength and sometimes direction of the association varies by social activity. We found that increased participation in religious activities was associated with subsequent declines in depressive symptoms, suggesting the possibility of a causal association. Our results highlight the importance of distinguishing between different types of social participation to understand how social engagement influences mental health and well-being. Further research is required to identify the specific mechanisms that explain the association between participation in religious activities and depressive symptoms. If the association is proven to be causal, however, our results suggest that policies encouraging or enabling older persons to maintain their affiliations with religious communities (e.g., by facilitating their attendance at religious events via public transport) may result in reduced levels of depressive symptoms among older persons.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Public Health, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (Simone Croezen, Mauricio Avendano, Alex Burdorf, Frank J. van Lenthe); and LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom (Mauricio Avendano).

M.A. was supported by a Starting Researcher grant from the European Research Council (ERC grant 263684), by the National Institute on Aging, US National Institutes of Health (awards R01AG040248 and R01AG037398), and by the McArthur Foundation Research Network on Ageing. Additional funding was obtained from the National Institute on Aging (grants U01 AG09740-13S2, P01 AG005842, P01 AG08291, P30 AG12815, R21 AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG BSR06-11, and OGHA 04-064) and the German Ministry of Education and Research, as well as various national sources (see www.share-project.org for a full list of funding institutions).

This study used data from SHARE wave 4, release 1.1.1 (March 28, 2013; Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.6103/SHARE.w4.111) and SHARE waves 1 and 2, release 2.6.0 (November 29, 2013; DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.260 and 10.6103/SHARE.w2.260) or SHARELIFE release 1 (November 24, 2010; DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w3.100). Data collection in SHARE has been funded primarily by the European Commission through the Fifth Framework Programme (project QLK6-CT-2001-00360 in the “Quality of Life” program), the Sixth Framework Programme (projects SHARE-I3 (grant RII-CT-2006-062193), COMPARE (grant CIT5-CT-2005-028857), and SHARELIFE (grant CIT4-CT-2006-028812)), and the Seventh Framework Programme (projects SHARE-PREP (grant 211909), SHARE-LEAP (grant 227822), and SHARE M4 (grant 261982)).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;1011:e1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. The epidemiological modelling of major depressive disorder: application for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One. 2013;87:e69637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro-Costa E, Dewey M, Stewart R, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and syndromes in later life in ten European countries: the SHARE study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaan B. Widowhood and depression among older Europeans—the role of gender, caregiving, marital quality, and regional context. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;683:431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lou VWQ, Chi I, Kwan CW, et al. Trajectories of social engagement and depressive symptoms among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong. Age Ageing. 2013;422:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiao C, Weng L-J, Botticello AL. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: an 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;252:453–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass TA, Mendes De Leon CF, Bassuk SS, et al. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health. 2006;184:604–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;783:458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkman LF, Glass TA. Social integration, social networks, social support and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:137–173. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;516:843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croezen S, Picavet HS, Haveman-Nies A, et al. Do positive or negative experiences of social support relate to current and future health? Results from the Doetinchem Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croezen S, Haveman-Nies A, Alvarado VJ, et al. Characterization of different groups of elderly according to social engagement activity patterns. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;139:776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bath PA, Deeg D. Social engagement and health outcomes among older people: introduction to a special section. Eur J Ageing. 2005;21:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Bonsdorff MB, Rantanen T. Benefits of formal voluntary work among older people. A review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;233:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin N, Ye X, Ensel WM. Social support and depressed mood: a structural analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;404:344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Gessa G, Grundy E. The relationship between active ageing and health using longitudinal data from Denmark, France, Italy and England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;683:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lash TL, Fink AK. Re: “Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study” [letter] Am J Epidemiol. 2003;1575:472–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardiner JC, Luo Z, Roman LA. Fixed effects, random effects and GEE: what are the differences? Stat Med. 2009;282:221–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell A, Jones K. Explaining fixed effects: random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Polit Sci Res Methods. 2015;31:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Firebaugh G, Warner C, Massoglia M. Fixed effects, random effects, and hybrid models for causal analysis. In: Morgan SL, ed. Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Publishing Company; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leyland AH. No quick fix: understanding the difference between fixed and random effect models. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;6412:1027–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirven N, Debrand T. Social participation and healthy ageing: an international comparison using SHARE data. Soc Sci Med. 2008;6712:2017–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, et al. The association between spiritual and religious involvement and depressive symptoms in a Canadian population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;19212:818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Abelson JM. Religious involvement and DSM-IV 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder among African Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;20010:856–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bobak M, Pikhart H, Pajak A, et al. Depressive symptoms in urban population samples in Russia, Poland and the Czech Republic. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ploubidis GB, Grundy E. Later-life mental health in Europe: a country-level comparison. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;645:666–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohli M, Hank K, Künemund H. The social connectedness of older Europeans: patterns, dynamics and contexts. J Eur Soc Policy. 2009;194:327–340. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croezen S, Avendano M, Burdorf A, et al. Does social participation decrease depressive symptoms in old age? In: Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Litwin H, et al., eds. Active Ageing and Solidarity Between Generations in Europe: First Results From SHARE After the Economic Crisis. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2013:391–402. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, et al. Data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol. 2013;424:992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prince MJ, Reischies F, Beekman AT, et al. Development of the EURO-D scale—a European Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro-Costa E, Dewey M, Stewart R, et al. Ascertaining late-life depressive symptoms in Europe: an evaluation of the survey version of the EURO-D scale in 10 nations. The SHARE project. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;171:12–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). ISCED 1997 International Standard Classification of Education. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: UNESCO Institute for Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robine J-M, Jagger C; Euro-REVES Group. Creating a coherent set of indicators to monitor health across Europe: the Euro-REVES 2 project. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13(3 suppl):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagger C, Gillies C, Cambois E, et al. The Global Activity Limitation Index measured function and disability similarly across European countries. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;638:892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allison PD. Fixed effects regression methods in SAS. Presented at the 31st Annual SAS Users Group International Conference, San Francisco, California, March 26–29, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hausman JA. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica. 1978;466:1251–1271. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge J. What Are We Weighting For? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. (NBER Working Paper Series, no. 18859). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegrist J, Wahrendorf M. Participation in socially productive activities and quality of life in early old age: findings from SHARE. J Eur Soc Policy. 2009;194:317–326. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piliavin JA, Siegl E. Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;484:450–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Ferraro KF. Volunteering and depression in later life: social benefit or selection processes? J Health Soc Behav. 2005;461:68–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1-2):29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krause N. Religiosity and self-esteem among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;505:P236–P246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison MO, Koenig HG, Hays JC, et al. The epidemiology of religious coping: a review of recent literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2001;132:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahrendorf M, von dem Knesebeck O, Siegrist J. Social productivity and well-being of older people: baseline results from the SHARE study. Eur J Ageing. 2006;32:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Luca G, Peracchi F. Survey participation in the first wave of SHARE. In: Börsch-Supan A, Jürges H, eds. The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe—Methodology. Mannheim, Germany: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2005:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blom AG, Schröder M. Sample composition 4 years on: retention in SHARE Wave 3. In: Schröder M, ed. Retrospective Data Collection in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. SHARELIFE Methodology. Mannheim, Germany: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2011:55–61. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.