Key messages

Teledermatology was found to be cost-effective through a reduction in referrals to secondary care.

Patient safety was not compromised and patient satisfaction was high in those responding to the survey.

Why this matters to me

I have worked in general practice in Ruislip for more than 20 years and like most general practitioners (GPs), my dermatology knowledge is limited. I had always referred cases that I was unsure of to secondary care to get a consultant opinion. Teledermatology was introduced locally in 2010 with the aim of reducing secondary care dermatology referrals. I wanted to evaluate whether costs were actually being reduced without compromising patient safety. I also wanted to find out how satisfied patients were with the teledermatology service provided. The medical student who was attending the practice at the time had an interest in pursuing a career in dermatology, as well as in the use of technology and telemedicine in primary care settings. She was keen to assist with the analysis and publication of this project.

Keywords: dermatology, general practice, primary health care, telemedicine

Abstract

Background

In the cost-constrained NHS and in the quest for rapid diagnosis, teledermatology is a tool that can be used within general practice to aid in the diagnosis of benign-looking skin lesions and reduce referrals to secondary care. The setting for the study was a single general practice of 6500 patients in suburban Greater London. The aim of the study was to determine: (1) whether teledermatology in a single general practice is cost-effective, (2) whether the correct types of cases are being referred, and (3) if patients are satisfied with the service.

Methods

Teledermatology was provided by a private provider. A trained member of staff took photographs in the practice. A consultant dermatologist carried out reporting. This is a retrospective analysis of case records over three years. The cases were adult patients (aged 18+) using teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin lesions thought to be benign by the general practitioner. Cost-effectiveness was calculated by considering savings made through reduced referral to secondary care, taking into account the cost of the service. To evaluate whether the correct cases were referred we reviewed whether the assessing dermatologist identified any previously undiagnosed skin cancer. Patient satisfaction assessment was performed using a standard questionnaire.

Results

Two hundred and forty-eight patients had teledermatology. These were patients who would have been referred to secondary care for a routine appointment. Of these, 102 were subsequently referred to secondary care and 146 were managed within the practice. Teledermatology saved £12 460 over the 3-year period. Patients were followed for up to 51 months and no lesions were found to be malignant. Ninety-seven percent of patients rated themselves as satisfied/very satisfied and 93% found the procedure comfortable/very comfortable. The median wait for the photos to be taken was 7 days, and 1–2 weeks for results.

Conclusions

Teledermatology has been shown to be cost-effective, with referrals identified correctly when employed in this general practice setting. Satisfaction with the service was high.

Introduction

Telemedicine is defined as the use of telecommunication technologies for the exchange of medical information across distances, and can be used for patient management.1 Teledermatology is a branch of telemedicine, and has been growing over the past few years. It involves the use of digital photography and dermatoscopy in a setting such as general practice, where photographs are taken, stored and forwarded to a dermatologist at another location. This technology has been enabled by the relatively recent introduction of high-speed broadband, the ability to take high-quality digital images, which are essential to making a diagnosis, and the introduction of a secure NHS network through which images can be sent while maintaining the security of patient's confidential information.

As early as 1996, methods for undertaking teledermatology had shown the potential benefits to patients; in terms of reduced travel and wait time, as well as the potential for reduced costs to the NHS.2 An HTA Assessment in 2006 was not able to draw conclusions regarding the clinical performance of the model studied, due to recruitment difficulties and drop-out rates.3

This is particularly important in the modern cost-constrained NHS, as well as with the introduction of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) placing the onus on general practices to contain costs while maintaining high-quality services. At the time of writing, the cost of a secondary care dermatology appointment is £1704 while the cost of a teledermatology appointment is £45 (Personal communication, Vantage diagnostics, February 15). Waiting times are also increasing for first outpatient appointments for dermatology, and in Hillingdon, this is 35 days for benign lesions.

Our study is the first in general practice in the UK to examine the cost-effectiveness of teledermatology for benign-looking skin lesions. Worldwide, there have been many studies on teledermatology – often in remote settings,5 developing countries or rural areas.6 There have also been studies in nursing homes7 and reviews have been published.8,9 A study was carried out in general practice in the Netherlands which showed a reduction in referrals of ˜ 20%.10

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of teledermatology in a general practice setting. The secondary objectives are to assess whether the correct patients are being referred to teledermatology, and whether they are satisfied with the service.

Methods

Setting

The setting for the study was a general practice of 6500 patients in a suburban area of Greater London.

Design

The local pathway for teledermatology was followed so that patients with benign-looking skin lesions who would previously have been directly referred to secondary care dermatology using the local provider were initially referred to the practice teledermatology service. In compliance with the pathway, patients were excluded if they met the 2-week wait criteria, had a dermatology condition affecting the genital area or had any extraordinary circumstances, e.g. post-transplant patients. Patients were given the choice between using teledermatology or referral to a consultant dermatologist at the local provider. All patients using teledermatology gave informed consent for the use of their photographs for this purpose. The service was also carried out in accordance with the BAD Quality Standards for Teledermatology.11

A member of staff who had been trained by Vantage used a Dermalite by Canon camera (supplied by Vantage) with a dermatoscope attached to the front to take photographs. The photographs were stored and forwarded via secure email (NHS net) to dermatologists in a secondary care setting, along with a referral letter. The dermatologists assessed these photographs and the results were sent back to the general practice. The doctor responsible for teledermatology phoned each patient with their results. Depending on the report and recommendation from the consultant dermatologist viewing the photos, some patients were referred for a face-to-face appointment with a dermatologist in secondary care. The remainder of the patients were managed in primary care for their condition. The teledermatology provider carries out a regular audit, in which 1 in every 10 reports provided is reviewed for diagnostic accuracy by an independent consultant. This is with the aim of ensuring diagnostic concordance and patient safety. The cost of referring all of these patients immediately to secondary derma- tology services was compared with the cost of teledermatology referrals plus any further referrals after this in order to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the system. To assess whether the correct patients were being referred to teledermatology it was considered whether there were any malignancies reported by the dermatologist via teledermatology that had been thought to be benign and so were sent for the service. Patients were followed up for between 15 and 51 months. Patient satisfaction was gathered using a standard NHS Teledermatology patient question- naire, which was sent out to patients once they had received their results. The questionnaire considered communication by the GP about the service, the length of time to appointment for photographs to be taken, the length of time for the patient to receive their results, their general satisfaction with the process and their comfort with the procedure. Patients were also asked whether they would recommend the service to other patients.

Results

Cost-effectiveness

During the period between November 2010 and November 2013, 248 patients were referred to the practice teledermatology service. Of the 248 patients, 102 (41%) were subsequently recommended by the dermatologist viewing the images to be referred for a secondary care appointment. The remaining 146 patients (59%) did not require a secondary care consultation and recommendations were given for management in general practice.

To calculate cost-effectiveness of this service, the following calculations were made: set-up costs for teledermatology including staff training and imaging kit were £1200 (Personal communication, Vantage diagnostics, February 15). The cost of referring one patient to secondary care is £170.4 The cost of referring one patient to teledermatology (including maintenance and use of the system, and the dermatologist's report) is £45 (Personal communication, Vantage diagnostics, February 15).

The cost of referring all 248 patients to secondary care immediately: 248 × £170 = £42 160. The cost of using the teledermatology service for all 248 patients: 248 × £45 = £11 160, plus the initial set-up implementation costs of £1200 = £12 360. In addition, there were 102 recommended referrals to secondary care at a cost of £170 each: 102 × £170 = £17 340. Therefore, the total spent on teledermatology, including subsequent referrals was £12 360 + £17 340 = £29 700 compared with £42 160 – a saving of £12 460.

Accuracy of referral

Over the 3-year period, three lesions sent by teledermatology were thought by the reviewing dermatologist to be possibly malignant. These patients were sent via a 2-week wait to a local secondary care provider. None of these patients turned out to have a malignancy (one haemangioma, one dysplastic naevus, one actinic keratosis). None of the other 99 patients subsequently referred to secondary care had a malignant lesion nor did any patients who were not referred to secondary care after teledermatology. The follow-up period has been between 15 and 51 months for these patients. Any lesions thought to be malignant by the GP at initial consultation were not referred to the teledermatology service and were referred directly to secondary care.

Patient satisfaction

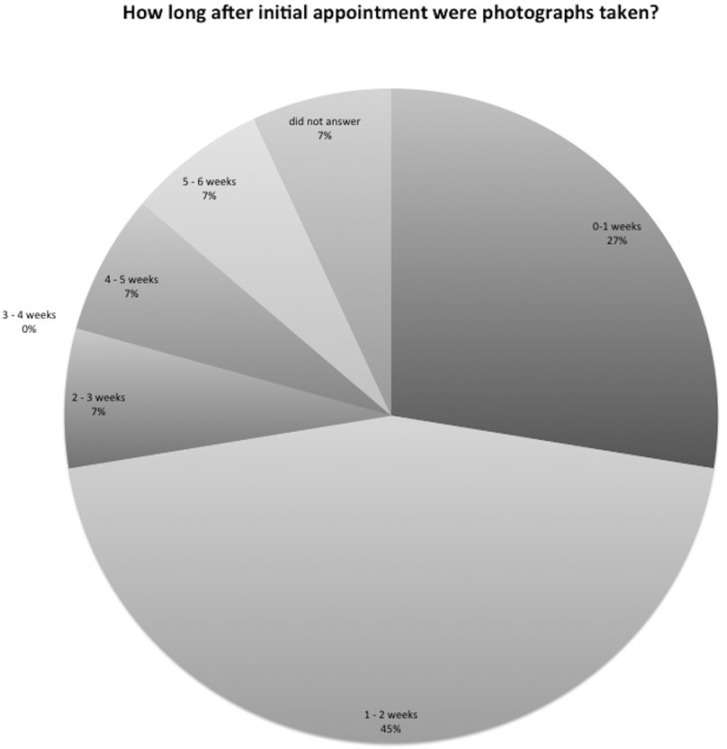

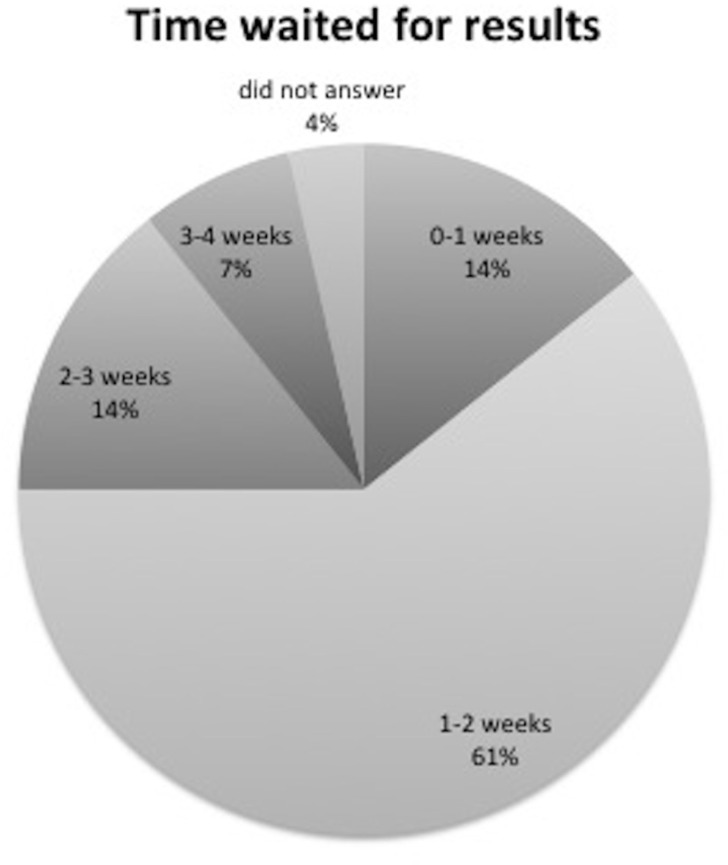

One hundred and twenty-nine patients returned patient satisfaction questionnaires. Of those, 100% said that the teledermatology service and process were explained to them by the GP/nurse, and 100% said that they would recommend the service to other patients. The median wait for the photos to be taken was 7 days and 1–2 weeks for results (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Conclusion

Over a 3-year period in a single general practice, we have found teledermatology to be cost-effective. The correct types of cases were referred. It also offered a high level of patient satisfaction. Overall, both the patients and the practice have benefitted from this service and it has saved the CCG money.

Discussion

This is the first study in a UK general practice setting to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of teledermatology when used to manage benign-looking skin lesions. Although teledermatology has been shown to be cost-effective, there are some limitations to this study. In our cost calculations, we did not include the time taken to train staff members to take and forward the photographs. Another factor possibly skewing our cost-effectiveness calculation is that more patients may have been referred into teledermatology than would have been sent directly to a secondary care dermatologist due to the convenience of the teledermatology service. However, this issue was discussed with all doctors in the practice prior to starting use of teledermatology – with agreement that the local pathway for referral to teledermatology would be followed. The main reason for referral to the service was diagnostic uncertainty and because the rapid reporting of the photographs provided a good educational opportunity for the doctors in the practice. The convenience for the patients who were seen at the surgery was also a factor. Relative to the number of people who had teledermatology, the number returning the survey (129) was low and may not have been fully representative of the group of patients as a whole, although patient satisfaction was uniformly high in those who did respond.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With thanks to Mrs Natalie Roe for administrative assistance.

Contributor Information

Judith Livingstone, GP Principal, Hillingdon CCG, UK.

Jessica Solomon, Medical Student, UCL, London, UK.

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

The UK National Research Ethics Service website was consulted and as this project is solely a service evaluation it is not managed as research within the NHS and so does not require ethical review by a NHS or Social Care Research Ethics Committee or management permission through the NHS R&D office.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wurm EM, Campbell TM, Soyer HP. (2008) Teledermatology: how to start a new teaching and diagnostic era in medicine. Dermatology Clinic 26: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DH, Critchton C, Macdonald A. et al. (1996) Teledermatology in the Highlands of Scotland. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2 Suppl 1:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowns IR, Collins K, Waters SJ. et al. (2006) Telemedicine in Teledermatology: a randomized controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment 10(43). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2012 Accessed 2 April 2014.

- 5.White H, Gould D, Mills W. et al. (1999) The Cornwall dermatology electronic referral and image-transfer project. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 5 Suppl 1:585–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgiss SG, Julius CE, Watdon HW. et al. (1997) Telemedicine for dermatology care in rural patients. Telemedicine Journal 3:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelickson BD, Homan I. (1997) Teledermatology in the nursing home. Archives of Dermatology 133:171–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero G, Garrido JA, Garcia-Arpa M. (2008) Telemedicine and teledermatology: concepts and applications. Actas dermosifiliográficas 99:506–22 [in Spanish]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pak HS. (2002) Teledermatology and teledermatopathology. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 21:179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eminovic N, de Keizer N, Wyatt J. et al. (2009) Teledermatologic consultation and reduction in referrals to dermatologists. A cluster randomized control trial. Archives of Dermatology 145:558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BAD Quality standards for teledermatology: using ‘store and forward’ images. March 2013.