Abstract

Obesity is now the third leading cause of preventable death in the US, accounting for 216,000 deaths annually and nearly 100 billion dollars in health care costs. Despite advancements in bariatric surgery, substantial weight regain and recurrence of the associated metabolic syndrome still occurs in almost 20-35% of patients over the long-term, necessitating the development of novel therapies. Our continually expanding knowledge of the neuroanatomic and neuropsychiatric underpinnings of obesity has led to increased interest in neuromodulation as a new treatment for obesity refractory to current medical, behavioral, and surgical therapies. Recent clinical trials of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in chronic cluster headache, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of targeting the hypothalamus and reward circuitry of the brain with electrical stimulation, and thus provide the basis for a neuromodulatory approach to treatment-refractory obesity. In this study, we review the literature implicating these targets for DBS in the neural circuitry of obesity. We will also briefly review ethical considerations for such an intervention, and discuss genetic secondary-obesity syndromes that may also benefit from DBS. In short, we hope to provide the scientific foundation to justify trials of DBS for the treatment of obesity targeting these specific regions of the brain.

Keywords: deep brain stimulation, obesity, hypothalamus, lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, metabolism, reward pathway, neuromodulation, food, behavior

Introduction and background

Obesity is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States. Obesity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer and is associated with a diminished quality of life and up to a 20-year decrease in life expectancy [1-4]. Currently, more than two-thirds of adult Americans are overweight and over one-third are obese [5-6]. Obesity is now the third leading cause of preventable death in the US, accounting for 216,000 deaths annually and nearly 100 billion dollars in health care costs [7-8]. Unfortunately, conservative measures are associated with high rates of relapse, and thus surgical treatment options have gained favor [9-11]. Advancements in bariatric surgery have allowed for significant weight loss in > 90% of patients [12]. Interestingly, in addition to the anatomic sequelae of obesity surgery, which impose mechanical limitations on the magnitude of food consumption, neuroendocrinological effects appear to play a significant role in the efficacy of such procedures. Several studies have demonstrated postoperative changes in levels of circulating gut peptides that project to the brain [13], thereby underscoring the critical importance of central nervous system’s feeding and satiety centers in the pathogenesis of obesity. Unfortunately, however, substantial weight regain and recurrence of the associated metabolic syndrome still occurs in almost 40% of patients over the long-term, necessitating the development of novel therapies [14-15].

Our continually expanding knowledge of the neuroanatomic and neuropsychiatric underpinnings of obesity has led to increased interest in neuromodulation, similar to other treatment-refractory disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) provides reversible electrical stimulation of neural circuitry and has been utilized as an effective and safe therapy for a wide variety of neurologic disorders [16-18]. While the precise mechanism of DBS remains unclear, it is well-established that high-frequency electrical stimulation clinically mimics the effects of neural ablative procedures [19-20]. However, the ability to titrate and/or reverse the effects of DBS make it the preferred method of neuromodulation [21-24]. Recent clinical trials of DBS in chronic cluster headache, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of targeting the hypothalamus and reward circuitry of the brain with electrical stimulation, and thus provide the basis for a neuromodulatory approach to treatment-refractory obesity [16, 25-27].

While the role of the hypothalamus in the neurophysiology of obesity has been well-established for decades [28-29], more recent investigation has verified the importance of the brain’s reward circuitry in the pathologic food-seeking behaviors typically seen in obesity [30-32]. This finding makes the nucleus accumbens (NAc) another favorable target for neuromodulation. In this study, we review the literature implicating these targets for DBS in the neural circuitry of obesity. We will also briefly review ethical considerations for such an intervention and discuss genetic secondary-obesity syndromes that may also benefit from DBS. In short, we hope to provide the scientific foundation to justify trials of DBS for the treatment of obesity targeting these specific regions of the brain.

Review

Lateral hypothalamus as a target for DBS

The hypothalamus is divided into multiple distinct functional regions; the main subregion that has received the most focus as a target for DBS is the lateral hypothalamus (LH). The LH has classically been recognized as the feeding center, providing anabolic control over the body's metabolism (Figure 1) [25]. The LH contains neurons that produce two orexinergic neuropeptides known as orexin and melanin-concentrating hormone (MHC). Intracerebroventricular infusion of either peptide elicits feeding [33]. Orexin-containing neurons project to various brain areas regulating feeding behavior. Over-expression of MCH in experimental models of obesity has been associated with insulin resistance and obesity, whereas MCH-knockout mice tend to be hypophagic and lean [34]. A variety of other peptides in addition to orexins have been implicated in LH activity, such as neuropeptide Y68, and agouti-related protein [35-39]. Moreover, the LH is one of the main regions within the hypothalamus that expresses the leptin receptor. Indeed, the activity of these orexin-containing neurons is mitigated by the presence of leptin, as endogenous leptin signaling in the hypothalamus restrains the overconsumption of calorically dense foods [40]. Animal studies and human genetic studies have confirmed that leptin deficiency is associated with a predisposition to obesity [41-43]. Whether by an inability of leptin to reach its neural target, a decrease in leptin isoforms, or decreased expression of leptin receptor [44-45], this “leptin resistance” lends further evidence that the LH is dysregulated, leading to the hypothesis that targeting this region with DBS may disrupt this aberrant circuitry and ameliorate the obese state [46-48].

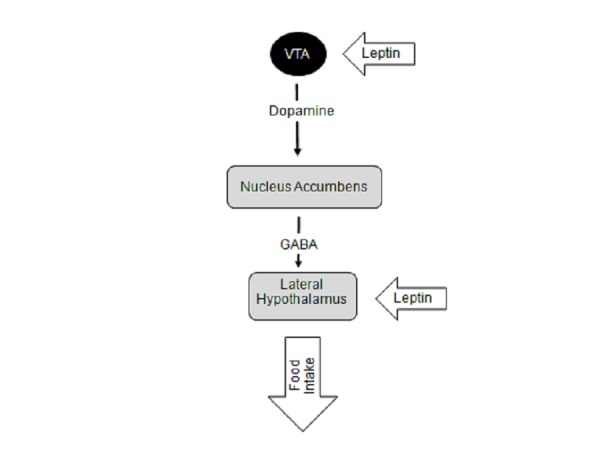

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting the deep brain stimulation (DBS) targets for obesity and their role in homeostatic pathway of energy balance.

The LH is responsible for providing anabolic feedback onto the autonomic nervous system effectors. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is the center of the reward pathway in the brain integrating inputs from various high cortical brain areas and the limbic system to reinforce certain beneficial behaviors, such as feeding. Integration of the reward pathways with feeding behavior begins with dopamine release from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons that project onto the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Within the NAc, there are neurons that projection onto the lateral hypothalamus (LH) which contain neurons that stimulate food intake. These nuclei also respond to various hormonal peptides, such as leptin, that are released by the the metabolic systems of the body that link food intake and energy metabolism to the reward pathways within the brain.

In support of this hypothesis, early lesion studies in rats induced leanness, suggesting an important role of the LH in exerting an anabolic effect on the body's metabolic systems [49-50] (Figure 1). Functionally impairing the endogenous activity of the LH with DBS is thought to mimic the effects of these lesions. This stems from experiences with subthalamic nucleus DBS for Parkinson disease, whereby chronic stimulation has the same clinical effects on parkinsonian features as subthalamotomy [51]. Indeed, bilateral DBS studies in rats have demonstrated a 16% weight loss [52]. Meanwhile, in a recent pilot study of LH DBS in humans, three morbidly obese patients who had previously failed to respond to gastric bypass surgery demonstrated an increase in resting metabolism at their three-year follow-up. Notably, extended follow-up demonstrated a sustained increase in resting metabolic rate with some weight loss in two out of three patients, and without any significant detrimental psychological consequences [53]. A key observation from this early work is the size of the region that DBS must modulate. An increase in metabolism can be achieved with a region as small as 2 mm2 despite the LH’s anatomical size measuring approximately 6 x 5 x 3.5 mm laterally, anteroposteriorly, and dorsoventrally, respectively [54]. These studies have identified the LH as a promising target for DBS for obesity, however, future clinical studies must verify the optimal location for LH DBS.

Nucleus accumbens and the reward pathway

Because it houses the hunger and satiety centers of the brain, the hypothalamus has traditionally been the focus of obesity neuromodulation, as detailed above [28-29]. However, many individuals with obesity exhibit many behavioral features of addiction-like behavior, such as binge eating, that is known to be related to dysfunctional reward circuitry in the brain [30-31, 55]. Feelings of craving, reward anticipation, consumption driven reward, and withdrawal are all modulated by the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic circuitry, which converges on the nucleus accumbens (NAc) [56-57]. Anatomically, the reward circuitry of the brain is composed of dopamine-secreting ventral tegmentum neurons that project to the NAc via the medial forebrain bundle (Figure 1) [58-60]. Access to such a highly palatable, high-caloric diet in rodents has been shown to heighten dopaminergic activity in the brain, which reinforces binge-eating behavior [61-62]. Multiple animal studies of chronic exposure to high-fat diets have demonstrated similar alterations in food consumption mediated by loss of both inhibitory control and withdrawal symptoms[63-64]. Mice conditioned to a high fat diet continuously endure harsh environments to maintain this palatable diet and demonstrate evidence of physiologic withdrawal when weaned from it [66]. A significant increase in markers of stress and decreased dopaminergic signaling within the NAc is seen in these animals after withdrawal from high fat diets [62].

In addition, rodent studies have demonstrated the biochemical, neuroendocrinological, neuroanatomical, and behavioral connections between the lateral hypothalamus and NAc (Figure 1) [65-66]. It is established that glutamate neurons in LH are a major projection site of NAc output neurons, and the NAc is the only striatal region that sends projections to LH [67]. The leptin signaling pathway as well as other gut-derived neuropeptides, such as hormone peptide YY, glucagon-like-peptide 1, and ghrelin, have also been found to project onto this circuitry (Figure 1) [46, 48, 68]. Ventral tegmental dopamine neurons express the leptin receptor and respond to leptin with a reduction in firing rate [68]. Direct administration of leptin to this midbrain structure caused decreased food intake while long-term knockdown of the leptin receptor led to increased food intake, locomotor activity, and sensitivity to highly palatable food. These data support a critical role for the leptin signaling pathway that involves this reward circuitry and the hypothalamic area in regulating feeding behavior. Moreover, this provides functional evidence for direct action of a peripheral metabolic signal on the reward circuit.

In humans, functional imaging studies have played a critical role in establishing the important involvement of the NAc in behaviors associated with obesity. fMRI studies of patients imagining intake of palatable foods found altered activation in the ventral striatum in individuals more at risk for future weight gain [69]. fMRI studies of response to images of high (vs. low) calorie foods or to anticipated receipt of a sweet taste in obese (vs. lean) participants found greater activity in the NAc [70-71]. Decreases in response of the NAc to high (vs. low) calorie food images were found in patients one-month post-roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery [72]. Two preliminary studies also found a trend for altered dopamine receptor binding potential in the ventral striatum postoperatively in five patients [73-74]. Thus, the NAc must be considered as a potential target for neuromodulation of reward circuitry to control the behavioral patterns of food dependence seen in obese individuals [75].

Nucleus accumbens as a target for DBS

Classically, the anatomical posterior border of the NAc has been at the level where the anterior commissure becomes discontinuous, and it is this posterior region of the nucleus that has achieved the best results when targeted for DBS for psychiatric disorders [76-77]. Proof-of-concept lesionectomy studies in rodent models have supported the potential efficacy of targeting the NAc with DBS for obesity. For example, in rats given stereotactic 6-OHDA infusions into the NAc, food hoarding behavior was virtually eliminated, and these animals experienced significant weight loss. These effects were readily reversed with levodopa administration [78]. DBS stimulation of the NAc has been performed in multiple animal studies with inconsistent results with regard to effects on feeding behavior, but most studies have not specifically examined the effects of DBS on animal models of obesity or eating disorders [79-81]. A recent study by Halpern, et al. demonstrated that DBS of the anteromedial NAc, but not the dorsal striatum, led to a decrease in binge-eating behavior, and this effect was mediated by dopamine signaling involving D2 receptors. This underscores the specificity of involvement of the mesolimbic pathways in food intake related reward pathways. The authors also examined the effects of chronic DBS of the NAc in diet-induced obese mice, and found that NAc stimulation led to decreased caloric intake, sustained weight loss, and improvements in features of Type 2 diabetes [82]. The NAc is a well-validated DBS target, and the safety and efficacy of this anatomic target in humans have already been demonstrated for treating disease processes, such as treatment-refractory depression, OCD, and alcoholism [83-85]. Thus, given the role of the NAc in food-seeking behavior, the NAc is a suitable target for a clinical trial for DBS treatment of refractory obesity.

Ethical considerations

Data from animal research [52, 86-87] as well as from recent case reports and pilot studies in humans [84, 88] have demonstrated the potential of obesity to be therapeutically targeted via DBS. Given the significant data accumulated from animal studies and case reports of obesity treatment with DBS, the specter of a clinical trial of DBS for obesity has raised some ethical considerations. There is significant overlap between obesity and addiction, raising concern for maladaptive behavior as a result of imperfectly executed neural manipulation of the CNS reward circuitry [89]. As with any new treatment for addictive behavior, the possibility for threatened autonomy in the face of behavior-altering treatment is often discussed [90]. Decision-making autonomy prior to treatment is typically preserved in obese patients without other psychiatric or developmental abnormalities as long as informed consent is obtained [91]. Reports of altered behavior ranging from emotional hyperactivity to increased impulsivity to suicidality have been reported [92-93], demonstrating that threatened autonomy can occur in the context of treatment. However, four basic demands for autonomous action include the ability to understand, appreciate, evaluate, and control one's actions in the context of treatment [91]. DBS for morbidly obese patients general satisfy the first three of these requirements, and ultimately goal of treatment would be to attain the fourth in terms of self-control over food consumption.

Given this, we firmly believe that the medical need and scientific justification for treatment of metabolic and eating disorders associated with obesity greatly outweigh the theoretical ethical risks as long as the treatment population is carefully selected. That is, a trial of DBS in obesity should be restricted to treatment refractory patients who have been cautiously evaluated by a multidisciplinary team of obesity specialists, ethicists, and neurosurgeons, and deemed medically and psychologically prepared for postoperative management. Stimulatory parameters of the hypothalamus and reward circuitry should also be carefully studied and modulated on an individual basis so as to not detrimentally alter metabolism or the reward circuitry. Targeting the NAc, in particular, could decrease the reinforcing sensation of consumption, serve as a substitute for the reward of eating, attenuate craving, inhibit a sense of withdrawal, or any combination of these effects. The question of whether attenuation of the reward sensation of food consumption could be achieved without altering a patient’s ability to experience other normal pleasure remains to be answered. In light of these considerations, extensive study is necessary to define the parameters of stimulation for optimal safety and efficacy. While animals studies will be crucial for defining neural targets, stimulatory parameters, laterality, and mechanism of DBS for obesity, the translation of animal models to human study is not always seamless, and human study will likely have to occur in parallel [94].

Secondary obesity syndromes

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is characterized by extreme hyperphagia, obesity, and intellectual disability, and is caused by a genetic defect resulting in absent expression of several imprinted genes in the 15q11-q13 region from the paternal chromosome 15 [95]. PWS patients are often morbidly obese due to their insatiable appetites [96]. One out of three PWS patients are over 200% ideal body weight, and there have been reports of overconsumption leading to stomach rupture in these patients [97]. The metabolic profile of PWS includes increased adipose to lean mass ratio [98-99], decreased total and resting energy expenditure [100], and elevated fasting ghrelin levels [101]. Despite the most radical medical and surgical interventions, PWS remains difficult to treat. In particular, bariatric surgery has had limited effectiveness and a concerning safety profile, given the increased medical comorbidity in this population [102].

PWS individuals likely have a disruption of basic satiety mechanisms leading them to consume more and for longer periods of time than obese individuals [103-104]. These disruptions manifest as post-meal hyperactivation of the hypothalamus, NAc, amygdala, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), OFC, and insula, regions involved in both the food satiety and reward circuitry [105-108]. fMRI studies have demonstrated that prior to consumption, individuals with PWS exhibit higher activity in reward/limbic regions (NAc, amygdala) and lower activity in subcortical hunger and satiety regions (hypothalamus, hippocampus), but post-consumption exhibit high activity in subcortical regions and lower activity in inhibitory pre-frontal cortical regions (posterior/lateral OFC, DLPFC) compared to controls. Thus, PWS not only leads to greater activation of reward and hunger centers in anticipation of food, but also disrupts inhibitory circuitry post-prandially [109].

PWS is a common link between food consumption and reward pathways in the brain that when disturbed leads to uncontrolled feeding and morbid obesity (Figure 1). As mentioned previously, LH and NAc are potential targets for PWS that have already been targeted in other disease states. Specifically, the LH has already been targeted via DBS for obesity [53-54] and headache [110] and the NAc for OCD, anxiety, addiction, and depression [76-77]. We propose that these same targets may be potential targets for DBS for PWS.

Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS) is a rare episodic hypersomnia disorder that is also characterized by hyperphagia, as well as hypersexuality and cognitive impairment [111-113]. Between episodes, clinical symptoms may resolve entirely. While the pathophysiology of this disorder is largely unknown [113], recent imaging studies have identified aberrations in a variety of deep brain nuclei and cerebral cortical areas.

A 2014 functional MRI (fMRI) study of KLS patients during acute episodes identified hyperactivation of the left thalamus, as well as hypoactivation of the anterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex [114]. Another recent study comparing brain perfusion scintigraphy in KLS patients and healthy controls identified hypoperfusion in the hypothalamus, thalamus, caudate nucleus, and frontal and temporal cortical associative areas [113, 115]. While significant progress remains to be made with regard to the pathophysiology underlying this disease, the identification of abnormalities in several deep brain structures raises the possibility of targeted DBS treatment for KLS.

Conclusions

In this study, we reviewed the literature implicating the lateral hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens, well-validated DBS targets, in the neural circuitry of obesity. We also presented the current data supporting DBS targeting of these foci to modulate both the metabolic and behavioral pathophysiology involved in treatment-refractory obesity, briefly reviewed ethical considerations for such an intervention, and discussed genetic secondary-obesity syndromes that may benefit from DBS. Though there have been no human studies to date specifically utilizing DBS towards the treatment of obesity, we have provided the scientific foundation and justification for a DBS trial for the treatment of obesity targeting these specific regions of the brain.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, Spadano JL, Laird N, Dietz WH, Rimm E, Colditz GA. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1581–1586. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Years of life lost due to obesity. Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. JAMA. 2003;289:187–193. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–1529. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Relationships between obesity and associated health factors with unemployment among low income women. Roe DA, Eickwort KR. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1976;31:193-4, 198-9, 203-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. PLoS Med. 2009;6:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The direct health care costs of obesity in the United States. Allison DB, Zannolli R, Narayan KM. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1194–1199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The weight loss experience: a descriptive analysis. Jeffery RW, Kelly KM, Rothman AJ, Sherwood NE, Boutelle KN. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:100–106. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, Mojica W, Arterburn D, Shugarman LR, Hilton L, Suttorp M, Solomon V, Shekelle PG, Morton SC. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:532–546. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000-2005. Sturm R. Public Health. 2007;121:492–496. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, Pareja BC, Callejas F, Pareja JC. Obes Surg. 2008;18:648–651. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neurohormonal pathways regulating food intake and changes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Orlando FA, Goncalves CG, George ZM, Halverson JD, Cunningham PR, Meguid MM. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weight gain after short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Christou NV, Look D, Maclean LD. Ann Surg. 2006;244:734–740. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metabolic syndrome after bariatric surgery. Results depending on the technique performed. Gracia-Solanas JA, Elia M, Aguilella V, Ramirez JM, Martinez J, Bielsa MA, Martinez M. Obes Surg. 2011;21:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deep brain stimulation in neurologic disorders. Halpern C, Hurtig H, Jaggi J, Grossman M, Won M, Baltuch G. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long-term management of DBS in dystonia: response to stimulation, adverse events, battery changes, and special considerations. Tagliati M, Krack P, Volkmann J, Aziz T, Krauss JK, Kupsch A, Vidailhet AM. Mov Disord. 2011;26:54–62. doi: 10.1002/mds.23535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long-term efficacy and mortality in Parkinson's disease patients treated with subthalamic stimulation. Toft M, Lilleeng B, Ramm-Pettersen J, Skogseid IM, Gundersen V, Gerdts R, Pedersen L, Skjelland M, Roste GK, Dietrichs E. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1931–1934. doi: 10.1002/mds.23817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Optical deconstruction of parkinsonian neural circuitry. Gradinaru V, Mogri M, Thompson KR, Henderson JM, Deisseroth K. Science. 2009;324:354–359. doi: 10.1126/science.1167093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus increases glutamate in the subthalamic nucleus of rats as demonstrated by in vivo enzyme-linked glutamate sensor. Lee KH, Kristic K, van Hoff R, Hitti FL, Blaha C, Harris B, Roberts DW, Leiter JC. Brain Res. 2007;1162:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subthalamotomy in Treatment of Parkinsonian Tremor. Andy OJ, Jurko MF, Sias FR, Jr Jr. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:860–870. doi: 10.3171/jns.1963.20.10.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EEG studies on patients with chronic obsessive-compulsive neurosis before and after psychosurgery (stereotaxic bilateral anterior capsulotomy) Bingley T, Persson A. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978;44:691–696. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(78)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long-term follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder treated by anterior capsulotomy: a neuropsychological study. Csigo K, Harsanyi A, Demeter G, Rajkai C, Nemeth A, Racsmany M. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilateral thalamotomy and pallidotomy as treatment for bilateral Parkinsonism. Krayenbuhl H, Wyss OA, Yasargil MG. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:429–444. doi: 10.3171/jns.1961.18.4.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Schwalb JM, Kennedy SH. Neuron. 2005;45:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hypothalamic stimulation in chronic cluster headache: a pilot study of efficacy and mode of action. Schoenen J, Di Clemente L, Vandenheede M, Fumal A, De Pasqua V, Mouchamps M, Remacle JM, de Noordhout AM. Brain. 2005;128:940–947. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: subthalamic nucleus target. Chabardès S, Polosan M, Krack P, Bastin J, Krainik A, David O, Bougerol T, Benabid AL. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:0. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partial reversibility of hypothalamic dysfunction and changes in brain activity after body mass reduction in obese subjects. van de Sande-Lee S, Pereira FR, Cintra DE, Fernandes PT, Cardoso AR, Garlipp CR, Chaim EA, Pareja JC, Geloneze B, Li LM, Cendes F, Velloso LA. Diabetes. 2011;60:1699–1704. doi: 10.2337/db10-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Relationship between feeding and satiation centers of the hypothalamus. Wyrwicka W, Dobrzecka C. Science. 1960;132:805–806. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3430.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neural correlates of food addiction. Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Orr PT, Stice E, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:808–816. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens reduces ethanol consumption in rats. Knapp CM, Tozier L, Pak A, Ciraulo DA, Kornetsky C. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MCH and feeding behavior-interaction with peptidic network. Griffond B, Risold PY. Peptides. 2009;30:2045–2051. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melanin-concentrating hormone overexpression in transgenic mice leads to obesity and insulin resistance. Ludwig DS, Tritos NA, Mastaitis JW, Kulkarni R, Kokkotou E, Elmquist J, Lowell B, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:379–386. doi: 10.1172/JCI10660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Cell. 1998;92:1. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Post-embryonic ablation of AgRP neurons in mice leads to a lean, hypophagic phenotype. Bewick GA, Gardiner JV, Dhillo WS, Kent AS, White NE, Webster Z, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. FASEB J. 2005;19:1680–1682. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3434fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB. Neuron. 1999;22:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leptin regulates energy balance and motivation through action at distinct neural circuits. Davis JF, Choi DL, Schurdak JD, Fitzgerald MF, Clegg DJ, Lipton JW, Figlewicz DP, Benoit SC. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leptin receptor action and mechanisms of leptin resistance. Munzberg H, Bjornholm M, Bates SH, Myers MG, Jr Jr. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:642–652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biologically inactive leptin and early-onset extreme obesity. Wabitsch M, Funcke JB, Lennerz B, Kuhnle-Krahl U, Lahr G, Debatin KM, Vatter P, Gierschik P, Moepps B, Fischer-Posovszky P. NEJM. 2015;372:48–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Triglycerides induce leptin resistance at the blood-brain barrier. Banks WA, Coon AB, Robinson SM, Moinuddin A, Shultz JM, Nakaoke R, Morley JE. Diabetes. 2004;53:1253–1260. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Socs3 deficiency in the brain elevates leptin sensitivity and confers resistance to diet-induced obesity. Mori H, Hanada R, Hanada T, Aki D, Mashima R, Nishinakamura H, Torisu T, Chien KR, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. Nature Med. 2004;10:739–743. doi: 10.1038/nm1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peptide hormones regulating appetite--focus on neuroimaging studies in humans. Schloegl H, Percik R, Horstmann A, Villringer A, Stumvoll M. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:104–112. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.A possible role of leptin-associated increase in soluble interleukin-2 receptor diminishing a clinical response to infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis: Comment on the article by Klaasen et al. Shin JI, Park SJ, Kim JH. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2833–2834. doi: 10.1002/art.30462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghrelin directly targets the ventral tegmental area to increase food motivation. Skibicka KP, Hansson C, Alvarez-Crespo M, Friberg PA, Dickson SL. Neuroscience. 2011;180:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.A critical evaluation of body weight loss following lateral hypothalamic lesions. Harrell LE, Decastro JM, Balagura S. Physiol Behav. 1975;15:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Self-stimulation and body weight in rats with lateral hypothalamic lesions. Keesey RE, Powley TL. Am J Physiol. 1973;224:970–978. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.4.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, Chabardes S, Fraix V, Ardouin C, Koudsie A, Limousin PD, Benazzouz A, LeBas JF, Benabid AL, Pollak P. NEJM. 2003;349:1925–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deep brain stimulation for treatment of obesity in rats. Sani S, Jobe K, Smith A, Kordower JH, Bakay RA. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:809–813. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/10/0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lateral hypothalamic area deep brain stimulation for refractory obesity: a pilot study with preliminary data on safety, body weight, and energy metabolism. Whiting DM, Tomycz ND, Bailes J, de Jonge L, Lecoultre V, Wilent B, Alcindor D, Prostko ER, Cheng BC, Angle C, Cantella D, Whiting BB, Mizes JS, Finnis KW, Ravussin E, Oh MY. J Neurosurg. 2013;119:56–63. doi: 10.3171/2013.2.JNS12903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaltenbrand GW, Wahren W. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Publishers; 1977. Atlas for Stereotaxy of the Human Brain. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reward mechanisms in obesity: new insights and future directions. Kenny PJ. Neuron. 2011;69:664–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The suppressive effect of an intra-prefrontal cortical infusion of BDNF on cocaine-seeking is Trk receptor and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase dependent. Whitfield TW Jr, Shi X, Sun WL, McGinty JF. J Neurosci. 2011;31:834–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4986-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nucleus accumbens shell and core dopamine: differential role in behavior and addiction. Di Chiara G. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137:75–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The addicted brain. Nestler EJ, Malenka RC. Sci Am. 2004;290:78–85. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0304-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Volkow ND, Li TK. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nrn1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Genetic analysis of drug addiction: the role of cAMP response element binding protein. Blendy JA, Maldonado R. J Mol Med (Berl) 1998;76:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s001090050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Decreases in dietary preference produce increased emotionality and risk for dietary relapse. Teegarden SL, Bale TL. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prefrontal-striatal pathway underlies cognitive regulation of craving. Kober H, Mende-Siedlecki P, Kross EF, Weber J, Mischel W, Hart CL, Ochsner KN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14811–14816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007779107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Low dopamine striatal D2 receptors are associated with prefrontal metabolism in obese subjects: possible contributing factors. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Thanos PK, Logan J, Alexoff D, Ding YS, Wong C, Ma Y, Pradhan K. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1537–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Altered levels of POMC, AgRP and MC4-R mRNA expression in the hypothalamus and other parts of the limbic system of mice prone or resistant to chronic high-energy diet-induced obesity. Huang XF, Han M, South T, Storlien L. Brain Res. 2003;992:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell control feeding behavior via the lateral hypothalamus. Maldonado-Irizarry CS, Swanson CJ, Kelley AE. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6779–6788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06779.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neural projections from nucleus accumbens to globus pallidus, substantia innominata, and lateral preoptic-lateral hypothalamic area: an anatomical and electrophysiological investigation in the rat. Mogenson GJ, Swanson LW, Wu M. J Neurosci. 1983;3:189–202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00189.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leptin receptor signaling in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates feeding. Hommel JD, Trinko R, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Liu ZW, Gao XB, Thurmon JJ, Marinelli M, DiLeone RJ. Neuron. 2006;51:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reward circuitry responsivity to food predicts future increases in body mass: moderating effects of DRD2 and DRD4. Stice E, Yokum S, Bohon C, Marti N, Smolen A. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. O'Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neuron. 2002;33:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Widespread reward-system activation in obese women in response to pictures of high-calorie foods. Stoeckel LE, Weller RE, Cook EW, 3rd 3rd, Twieg DB, Knowlton RC, Cox JE. Neuroimage. 2008;41:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selective reduction in neural responses to high calorie foods following gastric bypass surgery. Ochner CN, Kwok Y, Conceicao E, Pantazatos SP, Puma LM, Carnell S, Teixeira J, Hirsch J, Geliebter A. Ann Surg. 2011;253:502–507. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318203a289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Decreased dopamine type 2 receptor availability after bariatric surgery: preliminary findings. Dunn JP, Cowan RL, Volkow ND, Feurer ID, Li R, Williams DB, Kessler RM, Abumrad NN. Brain Res. 2010;1350:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alterations of central dopamine receptors before and after gastric bypass surgery. Steele KE, Prokopowicz GP, Schweitzer MA, Magunsuon TH, Lidor AO, Kuwabawa H, Kumar A, Brasic J, Wong DF. Obes Surg. 2010;20:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cue-reactors: individual differences in cue-induced craving after food or smoking abstinence. Mahler SV, de Wit H. PLoS One. 2010;5:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.The nucleus accumbens: a target for deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive- and anxiety-disorders. Sturm V, Lenartz D, Koulousakis A, Treuer H, Herholz K, Klein JC, Klosterkotter J. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.The Nucleus Accumbens beyond the Anterior Commissure: Implications for Psychosurgery. Lucas-Neto L, Mourato B, Neto D, Oliveira E, Martins H, Correia F, Goncalves-Ferreira A. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2014;92:291–299. doi: 10.1159/000365115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Disappearance of hoarding behavior after 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the mesolimbic dopamine neurons and its reinstatement with L-dopa. Kelley AE, Stinus L. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Suppression of attack behavior in cats by stimulation of ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. Goldstein JM, Siegel J. Brain Res. 1980;183:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.High-frequency deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens region suppresses neuronal activity and selectively modulates afferent drive in rat orbitofrontal cortex in vivo. McCracken CB, Grace AA. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12601–12610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Behavioral responses induced by electrical stimulation of the caudate nucleus in freely moving cats. Murer MG, Pazo JH. Behav Brain Res. 1993;57:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90056-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amelioration of binge eating by nucleus accumbens shell deep brain stimulation in mice involves D2 receptor modulation. Halpern CH, Tekriwal A, Santollo J, Keating JG, Wolf JA, Daniels D, Bale TL. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7122–7129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3237-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder: pilot study using a blinded, staggered-onset design. Goodman WK, Foote KD, Greenberg BD, Ricciuti N, Bauer R, Ward H, Shapira NA, Wu SS, Hill CL, Rasmussen SA, Okun MS. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Successful treatment of chronic resistant alcoholism by deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens: first experience with three cases. Muller UJ, Sturm V, Voges J, Heinze HJ, Galazky I, Heldmann M, Scheich H, Bogerts B. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:288–291. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1233489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, Kosel M, Brodesser D, Axmacher N, Joe AY, Kreft M, Lenartz D, Sturm V. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:368–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Changes in food intake with electrical stimulation of the ventromedial hypothalamus in dogs. Brown FD, Fessler RG, Rachlin JR, Mullan S. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:1253–1257. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.6.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Electrical stimulation of the ventromedial hypothalamus enhances both fat utilization and metabolic rate that precede and parallel the inhibition of feeding behavior. Ruffin M, Nicolaidis S. Brain Res. 1999;846:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smoking cessation and weight loss after chronic deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: therapeutic and research implications: case report. Mantione M, van de Brink W, Schuurman PR, Denys D. Neurosurg. 2010;66:218. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360570.40339.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Proposals to trial deep brain stimulation to treat addiction are premature. Carter A, Hall W. Addiction. 2011;106:235–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Denying autonomy in order to create it: the paradox of forcing treatment upon addicts. Caplan A. Addiction. 2008;103:1919–1921. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.The ethics of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Medicine, health care, and philosophy. Unterrainer M, Oduncu FS. 2015 Jan 18;[Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s11019-015-9622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.A multicentre study on suicide outcomes following subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Voon V, Krack P, Lang AE, Lozano AM, Dujardin K, Schupbach M, D'Ambrosia J, Thobois S, Tamma F, Herzog J, Speelman JD, Samanta J, Kubu C, Rossignol H, Poon YY, Saint-Cyr JA, Ardouin C, Moro E. Brain. 2008;131:2720–2728. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Behavioural disorders, Parkinson's disease and subthalamic stimulation. Houeto JL, Mesnage V, Mallet L, Pillon B, Gargiulo M, du Moncel ST, Bonnet AM, Pidoux B, Dormont D, Cornu P, Agid Y. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:701–707. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.What should animal models of depression model? Frazer A, Morilak DA. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical genetics, cytogenetics and molecular biology. Bittel DC, Butler MG. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prader-Willi syndrome: current understanding of cause and diagnosis. Butler MG. Am J Med Genet. 1990;35:319–332. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320350306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gastric rupture and necrosis in Prader-Willi syndrome. Stevenson DA, Heinemann J, Angulo M, Butler MG, Loker J, Rupe N, Kendell P, Cassidy SB, Scheimann A. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:272–274. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805b82b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Circulating adiponectin levels, body composition and obesity-related variables in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Kennedy L, Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Kalra SP, Torto R, Butler MG. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:382–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Body composition and fatness patterns in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with simple obesity. Theodoro MF, Talebizadeh Z, Butler MG. Obesity. 2006;14:1685–1690. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Energy expenditure and physical activity in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. American journal of medical genetics Part. Butler MG, Theodoro MF, Bittel DC, Donnelly JE. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:449–459. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Serum ghrelin levels are inversely correlated with body mass index, age, and insulin concentrations in normal children and are markedly increased in Prader-Willi syndrome. Haqq AM, Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S, Stadler DD, Rosenfeld RG, Pratt KL, LaFranchi SH, Purnell JQ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:174–178. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Critical analysis of bariatric procedures in Prader-Willi syndrome. Scheimann AO, Butler MG, Gourash L, Cuffari C, Klish W. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:80–83. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000304458.30294.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eating behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome, normal weight, and obese control groups. Lindgren AC, Barkeling B, Hagg A, Ritzen EM, Marcus C, Rossner S. J Pediatr. 2000;137:50–55. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Characteristics of abnormal food-intake patterns in children with Prader-Willi syndrome and study of effects of naloxone. Zipf WB, Berntson GG. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:277–281. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Satiety dysfunction in Prader-Willi syndrome demonstrated by fMRI. Shapira NA, Lessig MC, He AG, James GA, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:260–262. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.039024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Neural mechanisms underlying hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Holsen LM, Zarcone JR, Brooks WM, Butler MG, Thompson TI, Ahluwalia JS, Nollen NL, Savage CR. Obesity. 2006;14:1028–1037. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Enhanced activation of reward mediating prefrontal regions in response to food stimuli in Prader-Willi syndrome. Miller JL, James GA, Goldstone AP, Couch JA, He G, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:615–619. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neural representations of hunger and satiety in Prader-Willi syndrome. Hinton EC, Holland AJ, Gellatly MS, Soni S, Patterson M, Ghatei MA, Owen AM. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:313–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Importance of reward and prefrontal circuitry in hunger and satiety: Prader-Willi syndrome vs simple obesity. Holsen LM, Savage CR, Martin LE, Bruce AS, Lepping RJ, Ko E, Brooks WM, Butler MG, Zarcone JR, Goldstein JM. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:638–647. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Neurostimulation for primary headache disorders: Part 2, review of central neurostimulators for primary headache, overall therapeutic efficacy, safety, cost, patient selection, and future research in headache neuromodulation. Jenkins B, Tepper SJ. Headache. 2011;51:1408–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Recurrent hypersomnia: a review of 339 cases. Billiard M, Jaussent I, Dauvilliers Y, Besset A. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Update on hypersomnias of central origin. Drakatos P, Leschziner GD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:572–580. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kleine-Levin syndrome: a review. Miglis MG, Guilleminault C. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;6:19–26. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S44750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Functional magnetic resonance imaging in narcolepsy and the kleine-levin syndrome. Engstrom M, Hallbook T, Szakacs A, Karlsson T, Landtblom AM. Front Neurol. 2014;5:105. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.A case of Kleine-Levin syndrome examined with SPECT and neuropsychological testing. Landtblom AM, Dige N, Schwerdt K, Safstrom P, Granerus G. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105:318–321. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.1c162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]