Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of premature ejaculation (PE) among adult Asian males presented with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and characterize its association with other clinical factors.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary medical center to determine the prevalence of PE among adult male participants with LUTS during the Annual National Prostate Health Awareness Day. Basic demographic data of the participants were collected. All participants were assessed for the presence and severity of LUTS using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and for the presence of PE using the PE diagnostic tool. Digital rectal examination was performed by urologists to obtain prostate size. LUTS was further categorized into severity, storage symptoms (frequency, urgency, and nocturia), and voiding symptoms (weak stream, intermittency, straining, and incomplete emptying) to determine their association with PE. Data were analyzed by comparing the participants with PE (PE diagnostic tool score ≥11) versus those without PE, using the independent t test for continuous data, Mann–Whitney U test for ordinal data, and Chi-square test for nominal data. The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 101 male participants with a mean ± standard deviation age of 60.75 ± 10.32 years were included. Among the participants, 33% had moderate LUTS, and 7% severe LUTS. The most common LUTS was nocturia (33%). The overall prevalence of PE was 27%. There was no significant difference among participants with PE versus those without PE in terms of age, marital status, prostate size, or total IPSS score. However, significant difference between groups was noted on the level of education (Mann–Whitney U, z = −1.993, P = 0.046) where high educational status was noted among participants with PE. Likewise, participants with PE were noted to have more prominent weak stream (Mann–Whitney U, z = −2.126, P = 0.033).

Conclusions

Among the participants consulted with LUTS, 27% have concomitant PE. Educational status seems to have an impact in the self-reporting of PE, which may be due to a higher awareness of participants with higher educational attainment. A significant association between PE and weak stream that was not related to prostate size suggests a neuropathologic association.

Keywords: Factor association, Lower urinary tract symptoms, Premature ejaculation

1. Introduction

Every year, the Philippine Urological Association (PUA) celebrates Prostate Health Awareness Month with National Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) Day. This is a nationwide effort to promote awareness in men regarding prostate diseases such as benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. This is conducted by urologists in several participating institutions. Most of the participants come in for consultation due to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Out of 925 participants in 2013, more than half (61%) were identified as cases of LUTS, with 57% reported to have moderate to severe LUTS.1

LUTS are common in men and have been shown to have increased frequency and severity with age.2 Symptoms of male sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, and hypoactive desire were previously assumed to be only natural consequences of aging.3 However, the latest evidence from epidemiological studies suggests that these symptoms are actually associated with LUTS.2 Several community-based studies have also shown strong correlations between the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, especially erectile dysfunction, and the severity of LUTS with increasing age.4

Premature ejaculation (PE), one of the components of male sexual dysfunction, is also seen in the elderly as a primary or secondary condition.4 Although several studies have already defined the association between male sexual dysfunction (specifically erectile dysfunction) and LUTS, only few correlations have been made between premature ejaculation alone and LUTS. Common causes for this are poor detection of this symptom and under-reporting of cases.5 This study therefore aims to determine the prevalence of PE among adult Asian males and characterize its association with LUTS and other clinical factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Data gathering

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study that included all male participants during the Annual National DRE Day in the Philippines conducted in June 2014 at St. Luke's Medical Center (Quezon City, Philippines). Demographic data obtained were age, marital status, educational attainment, and occupation including comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus. All participants were assessed by urologists for the presence of LUTS using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and PE using the PE Diagnostic Tool (PEDT). A PEDT score ≥11 was categorized as PE. The IPSS was further categorized into total score (IPSS sum), storage symptom domains (FUN: frequency, urgency, and nocturia), and voiding symptom domains (WISR: weak stream, intermittency, straining, and residual urine). DRE was also performed to obtain prostate size estimates.

2.2. Data analysis

Data gathered were encoded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Demographic data of the participants were summarized. The clinical characteristics differences among LUTS participants with PE versus without PE were statistically analyzed. The independent t test was used for analyzing continuous data such as age, IPSS sum, storage symptom score, and voiding symptom score. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied to analyze ordinal data with a Likert scale 1–5 of individual IPSS symptom domains, prostate size range of 20–60 g, and educational attainment (Table 1) from primary school to doctorate degree. The Chi-square test was done to analyze nominal data such as the presence or absence of comorbidity (hypertension and diabetes mellitus) and marital status. The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of participants.

| No. of patients = 101 | Count (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | Single | 10 (9.9) |

| Married | 79 (78.2) | |

| Separated | 5 (5) | |

| Widowed | 7 (6.9) | |

| Occupation | Retired | 63 (62.4) |

| Employed | 38 (37.6) | |

| Education | Primary | 7 (6.9) |

| Secondary | 33 (32.7) | |

| College | 54 (53.5) | |

| Postgraduate | 3 (3) | |

| Master | 4 (4) | |

| Doctorate | 0 | |

| Comorbid illness | Hypertension | 75 (74.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 (20.8) | |

3. Results

A total of 101 male participants attended the Annual National DRE Day conducted at our medical center, all of which were included in the study. The mean age of the participants was 61 years ranging from 36 years to 86 years. Most (78.2%) of the participants were married; 54% of the participants had graduated college and 63% were retired; 74.3% had comorbidity of hypertension, and 20.8% had diabetes mellitus. The demographic profile is summarized in Table 1.

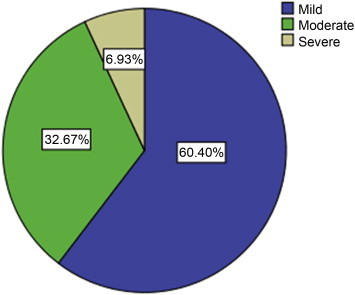

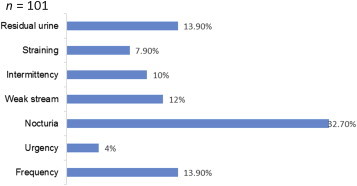

The mean ± standard deviation IPSS was 5.79 ± 6.59; 60.40% had a score <8, which is categorized as mild LUTS; 32.67% scored 8–19, categorized as moderate LUTS; and only 6.93% had severe LUTS with a score of >19. Distribution of LUTS severity is illustrated in Fig. 1. Among the participants, 13.9% (n = 14) scored ≥3 in frequency, 4% (n = 4) scored ≥3 in urgency, 32.7% (n = 33) scored ≥3 in nocturia, 12% (n = 12) scored ≥3 in weak stream, 10% (n = 10) scored ≥3 in intermittency, 7.9% (n = 8) scored ≥3 in straining, and 13.9% (n = 14) scored ≥3 in residual urine. In clustering the LUTS score, 50.6% of the participants had storage symptoms whereas 43.8% had voiding symptoms. Distributions of individual LUTS domains are described in Fig. 2. The mean age of participants with an approximate 20-g prostate size by DRE was 56.38 years, ∼30 g was 62.16 years, ∼40 g was 63.96 years, ∼50 g was 62.5 years, and ∼60 g was 61.25 years (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Severity of lower urinary tract symptoms of participants.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of individual lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) symptom domains.

Table 2.

Prostate size by digital rectal examination (DRE) distribution with age means.

| Mean age (y) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prostate size by DRE (g) | 20 | 56.38 |

| 30 | 62.16 | |

| 40 | 63.96 | |

| 50 | 62.50 | |

| 60 | 61.25 | |

According to the PEDT assessments of the participants, 26.7% (27) of the participants scored ≥11, which signifies the presence of PE, whereas 16.8% (17) scored 9–10 indicating that PE is probably present. Independent t test, used to determine the difference among participants with PE versus without PE, showed no significant differences in terms of age, IPSS sum, storage symptom score, or voiding symptom score (Table 3). Mann–Whitney U analysis showed that educational attainment has significant association with the presence of PE, where higher educational status was noted among participants with PE (Mann–Whitney U, z = −1.993, P = 0.046). Likewise, participants with PE were noted to have more prominent weak stream (Mann–Whitney U, z = −2.126, P = 0.033); however, PE was not associated with prostate size (Table 4). There was no significant between group difference noted in the Chi-square analysis on comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes) and marital status (Table 5).

Table 3.

Independent t test analysis between participants with premature ejaculation (PE) versus without PE in terms of age, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) sum, storage symptom score (FUN), and voiding symptom score (WISR).

| Continuous variables | Without PE (n = 74), mean ± SD | With PE (n = 27), mean ± SD | 95% confidence interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 60.1 ± 10 | 62.6 ± 11 | −7.1–2.14 | 0.29 |

| IPSS sum | 5.3 ± 6 | 7.1 ± 7 | −4.7–1.14 | 0.23 |

| FUN | 2.9 ± 3 | 3.3 ± 3 | −1.8–1.01 | 0.6 |

| WISR | 2.4 ± 4 | 3.9 ± 5 | −3.18–3.18 | 0.11 |

FUN, frequency, urgency, and nocturia; WISR, weak stream, intermittency, straining, and residual urine.

Table 4.

Mann–Whitney U test between participants with premature ejaculation (PE) and without PE in terms of individual International Prostate Symptom Score, prostate size, and education.

| Ordinal variables | Without PE (n = 74), mean rank | With PE (n = 27), mean rank | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 47.84 | 59.67 | −1.993 | 0.046 |

| Quality of life score | 49.23 | 55.85 | −1.165 | 0.244 |

| Frequency | 50.51 | 52.35 | −0.302 | 0.763 |

| Urgency | 51.46 | 49.74 | −0.369 | 0.712 |

| Nocturia | 49.03 | 56.39 | −1.149 | 0.251 |

| Weak stream | 47.78 | 59.83 | −2.126 | 0.033 |

| Intermittency | 50.13 | 53.39 | −0.637 | 0.524 |

| Straining | 49.63 | 54.76 | −0.991 | 0.322 |

| Residual | 50.12 | 53.41 | −0.554 | 0.579 |

| Prostate size | 50.19 | 53.22 | −0.479 | 0.632 |

Table 5.

Chi-square analysis between participants with premature ejaculation (PE) and without PE in terms of participants with comorbidity and marital status.

| Nominal variables | Without PE | With PE | Chi-square | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Without | 18 | 6 | 0.048 | 0.83 |

| With | 56 | 21 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | Without | 59 | 21 | 0.046 | 0.83 |

| With | 15 | 6 | |||

| Marital status | Single | 6 | 4 | 4.365 | 0.23 |

| Married | 61 | 18 | |||

| Separated | 2 | 3 | |||

| Widowed | 5 | 2 | |||

4. Discussion

In 2014, the PUA celebrated prostate health awareness month with the theme Ikaw na MAN (You're the MAN) focusing not only on prostate diseases but also urinary tract and sexual related problems. During the Annual National DRE Day 2014, more men participated in our medical center than in the previous year—101 participants compared with 59 participants in 2013.1 This shows that the PUA was successful in promoting prostate health awareness and more men are now becoming concerned about their health.

Based on our study, the mean age of participants was 61 years, which is comparable to other studies in that over one third of men aged 50 years or more are living with moderate to severe LUTS.2 Voiding symptoms are most common in men with LUTS, but are generally less bothersome than storage symptoms, which are typically the reason for men seeking medical advice.2 This is in contrast with our study where 50.6% of the participants present with storage symptoms, whereas voiding symptoms show only 43.8%. Nocturia is the most common symptom reported (32.7%) together with frequency (13.9%) and residual urine (13.9%). A study described that an isolated nocturia can be common, particularly in aging men, with a recent meta-analysis estimating a prevalence of 30–60% in men aged >70 years.6

The most common prostate size in the mean age of 62.16 years is 30 g whereas 40-g prostate sizes were seen in the mean age of 63.96 years. This relates that the prostate enlarges with aging. In addition, although LUTS are sometimes associated with urinary flow and prostate size, there is substantial evidence that men can have symptoms even in the absence of enlarged prostate on physical examination.6 This is partly because lower urinary tract symptoms can be caused by multiple mechanisms, including prostate, bladder smooth muscle tone and contractility.6

PE was first described a century ago; however, its definition has been debatable since then due to its ambiguity.7 The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 2013) has defined PE using the parameter of approximately 1-min intravaginal ejaculatory latency time. The DSM-5 also listed potential exclusionary conditions to include nonsexual mental disorders, severe relationship distress or other significant stressors, and substance/medication use or other medical disorders, which may result in early ejaculations. These criteria were intended to eliminate cases of premature ejaculation resulting secondarily from psychological and/or medical factors.7,8 The International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) in 2013 developed a definition grounded in clearly definable scientific criteria. The committee proposed an evidence-based unified definition of both lifelong PE and acquired PE.9 The ISSM described three current questionnaires used in the diagnosis of PE; the PEDT has a modest database, and is readily available for clinical use.5 Several studies have established the validity and reliability of PEDT that correlate well with the objective assessment by intravaginal ejaculatory latency time10,11; due to its simplicity and availability, our study utilized this tool to screen the presence of PE among the participants.

The prevalence of PE among participants with a complaint of LUTS in our study was 26.7% (n = 27) whereas 16.8% (n = 17) had probable PE. This is comparable with a study in Korea, where PEDT have diagnosed PE in 12.1% (35/290) and probable PE in an additional 11.7% (34/290).4 It is clear that PE is highly prevalent and, globally, approximately 30% of all men can be considered to have the condition regardless of age group.12 Similar to our study, the PE Perceptions and Attitudes Study reported that many countries did not show an increased prevalence of PE with increasing age.13 However, according to the data of the Korean Society for Sexual Medicine and Andrology, their study demonstrated an increased PE prevalence with increasing age.4 The same Korean study also described that there is significant correlation between LUTS and PE particularly among the age 60–79 years group (r = 0.292, P = 0.007)4; however, the PEDT score among the age 40–59 years group was not correlated with storage symptoms (r = 0.327, P = 0.077) or voiding symptoms (r = 0.223, P = 0.235).4 In congruence, our study results also showed that the storage symptoms and PE has no association (P = 0.600), as well as voiding symptoms and PE (P = 0.108).

The educational level of the participants correlates well with the presence or absence of PE. In particular, high education was associated with increased incidence of PE showing a significant association (Mann–Whitney U, z = −1.993, P = 0.046). Our study has demonstrated that educational status seems to have an impact in the self-reporting of PE of the participants, which may be due to higher awareness with higher educational attainment. It suggests that participants who are aware about the condition PE are more likely to volunteer PE symptoms. It is recommended that clinicians should always utilize the screening questions for PE to give the appropriate treatment,5 because participants are often unwilling to volunteer their symptoms on PE.14

The mechanism of PE requires emission that involves deposition fluid from the ampullary vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate gland into the posterior urethra15; and expulsion phase that involves closure of the bladder neck, followed by the rhythmic contractions of the urethra by pelvic–perineal and bulbospongiosus muscles, and intermittent relaxation of the external urethral sphincters.16 Sympathetic motor neurons control the emission phase of ejaculation reflex, and expulsion phase is executed by somatic and autonomic motor neurons. These motor neurons are located in the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral spinal cord and are activated in a coordinated manner when sufficient sensory input to reach the ejaculatory threshold has entered the central nervous system.17,18

Our study showed a significant association between PE and weak stream (Mann–Whitney U, z = −2.126, P = 0.033) that was not related to prostate size (Mann–Whitney U, z = −0.479, P = 0.632), which may suggest a neuropathologic association. A recent study by Choi et al.,19 although statistically not significant, also showed a lower maximum voiding flow velocity, and average flow velocity among their LUTS patients with PE as compared to patients with LUTS only (12.68 ± 3.96 vs. 17.51 ± 7.99, P = 0.07; 6.50 ± 2.27 vs. 9.00 ± 3.86, P = 0.06, respectively).

It may be possible that a neurologic problem causing weak bladder contraction such as neurogenic bladder may also cause PE because autonomic motor neurons for bladder contraction and ejaculation are located in the same area. A study described the possible cause of the link between LUTS, erectile dysfunction, and PE is overactivation of the autonomic nervous system and increased sympathetic nervous system activity. According to this hypothesis, LUTS could result from sympathetic nervous system tone, which induces the occurrence of urinary storage symptoms owing to the contraction of smooth muscles in the prostate gland and urinary bladder. Erectile dysfunction occurs as a result of smooth muscle contraction in the corpus cavernosum, whereas PE occurs as a result of smooth muscle contraction in the prostate, seminal vesicle, vas deferens, and epididymis.4

This study was limited to a clinical based single session assessment of participants. No follow up or additional objective diagnostic examination such as a urodynamic study with sphinteric activity assessment were done to confirm the presence of and association between PE and LUTS. Therefore, a larger-scale study with follow up of participants with objective assessment and additional risk factor identification (such as body mass index, smoking status, and psychological factors) is recommended for future studies to confirm our findings and additional analyses.

5. Conclusion

Among the participants consulted with LUTS, 27% have concomitant PE. Educational status seems to have an impact in the self-reporting of PE, which may be due to higher awareness of participants with higher educational attainment. A significant association between PE and weak stream that was not related to prostate size, suggests a neuropathologic association.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chua M.E., Lapitan M.C., Morales M.L., Jr., Roque A.B., Domingo J.K. Philippine urological residents association (PURA). 2013 annual national digital rectal exam day: impact on prostate health awareness and disease detection. Prostate Int. 2014;2:31–36. doi: 10.12954/PI.13039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees J., Bultitude M., Challacombe B. The management of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3861. g3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen R.C., Giuliano F., Carson C.C. Sexual dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) Eur Urol. 2005;47:824–837. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Um J.D., Kang D.I., Yoon J.H., Min K.S. Erratum: Correction of Title. Correlation between lower urinary tract symptoms and premature ejaculation in Korean men older than 40 years old. Korean J Urol. 2014;55(6):434. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althof S.E., McMahon C.G., Waldinger M.D. An update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation (PE) J Sex Med. 2014;2:1392–1422. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingsworth J.M., Wilt T.J. Lower urinary tract symptoms in men. BMJ. 2014;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4474. g4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cayan S., Serefoğlu E.C. Advances in treating premature ejaculation. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:55. doi: 10.12703/P6-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . bookpointUS; Bangalore, India: 2013. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM 5; pp. 445–446. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serefoglu E.C., McMahon C.G., Waldinger M.D. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1423–1441. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kam S.C., Han D.H., Lee S.W. The diagnostic value of the premature ejaculation diagnostic tool and its association with intravaginal ejaculatory latency time. J Sex Med. 2011;8:865–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serefoglu E.C., Cimen H.I., Ozdemir A.T., Symonds T., Berktas M., Balbay M.D. Turkish validation of the premature ejaculation diagnostic tool and its association with intravaginal ejaculatory latency time. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:139–144. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montorsi F. Prevalence of premature ejaculation: a global and regional perspective. J Sex Med. 2005;2:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porst H., Montorsi F., Rosen R.C., Gaynor L., Grupe S., Alexander J. The premature ejaculation prevalence and attitudes (PEPA) survey: prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. Eur Urol. 2007;51:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benyó M. The significance of premature ejaculation. Cent Eur J Urol. 2014;67:79–80. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2014.01.art17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Böhlen D., Hugonnet C.L., Mills R.D., Weise E.S., Schmid H.P. Five meters of H2O: the pressure at the urinary bladder neck during human ejaculation. Prostate. 2000;44:339–341. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000901)44:4<339::aid-pros12>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Master V.A., Turek P.J. Ejaculatory physiology and dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:363–375. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70145-2. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deGroat W.C., Booth A.M. Physiology of male sexual function. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:329–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-2-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Truitt W.A., Coolen L.M. Identification of a potential ejaculation generator in the spinal cord. Science. 2002;297:1566–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1073885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi J.H., Hwa J.S., Kam S.C., Jeh S.U., Hyun J.S. Effects of tamsulosin on premature ejaculation in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Mens Health. 2014;32:99–104. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]