Aging is a universal and complex process hallmarked by progressive molecular alterations that lead to a decline in the ability of living beings to maintain homeostasis and overcome stress, damage and disease resulting from intrinsic and extrinsic threats over time (1). At the organismal level, stem cells play a fundamental role in the maintenance of tissue integrity and their functional and proliferative exhaustion is a major cause of aging (2). Hematopoietic stem cells HSCs, which reside in the bone marrow and give rise to all blood cell types, are one of the favored model for the study of stem cell aging. However, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the aging of HSCs remain unknown. Sirtuins, a family of seven nutrient sensing proteins (SIRT1–SIRT7) that regulate both gene expression and protein function, have captured the attention of the aging field due to the multiple pathways they orchestrate that are associated with age-related processes and longevity.

In this issue of Science, Mohrin et al. describe a novel metabolic checkpoint mediated by SIRT7 in HSCs that integrates five of the nine hallmarks of aging: mitochondrial function, nutrient sensing, proteins homeostasis, gene expression and stem cell proliferation (Mohrin et al.). The analysis of the SIRT7 interactome has allowed the authors for the identification of Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1 (NRF1) as a new sirtuin partner. The interaction between NRF1 and SIRT7 suppresses the mitochondrial translational machinery and leads to depletion of mitochondrial activity. Consistent with the metabolic sensing nature of sirtuins, SIRT7 levels increase with nutrient deprivation, which in cooperation with NRF1 hampers mitochondrial function, yet promotes cell survival by promoting nutritional stress resistance. While loss of mitochondrial proteostasis triggers the unfolded protein response (UPRmt), the interaction between SIRT7 and NRF1 reduces mitochondrial protein folding stress.

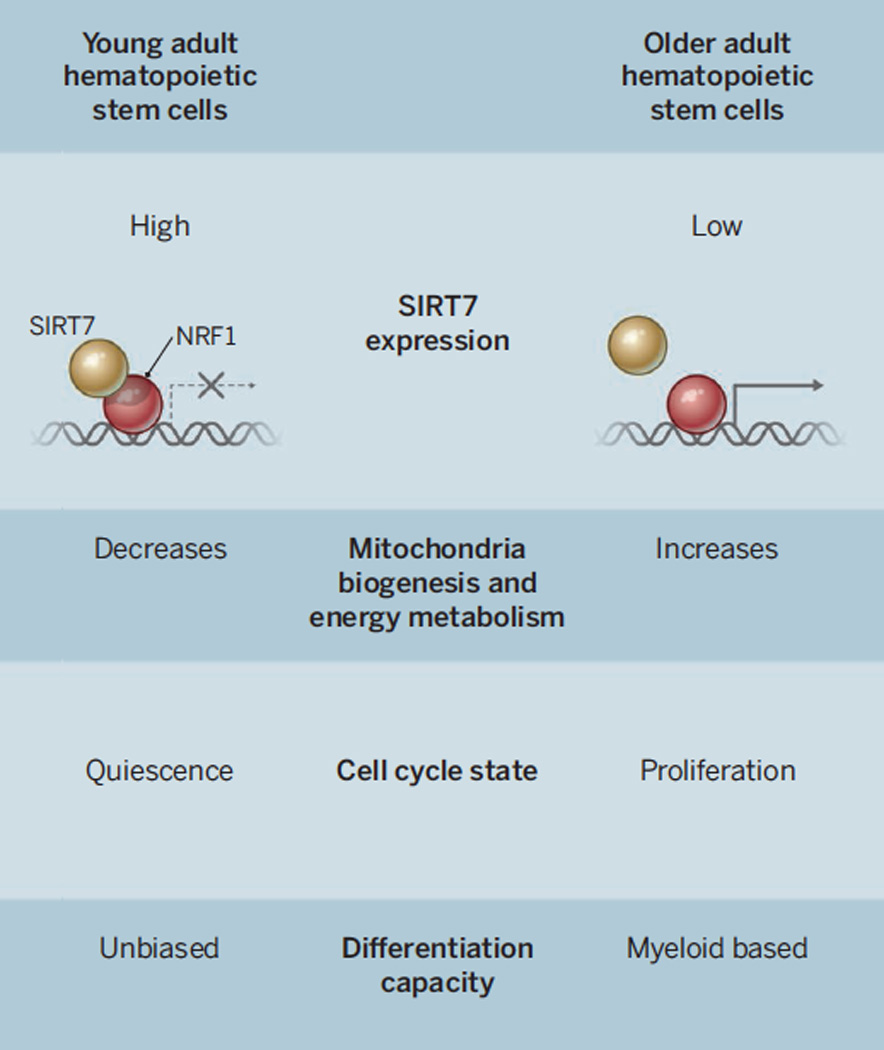

Metabolic reprogramming plays fundamental roles during organismal development, cellular reprogramming and differentiation (3). The high levels of SIRT7 expression in HSCs, and the fact that the quiescent state of stem cells is characterized by high glycolytic rates and low mitochondrial activity, led Mohrin et al. to explore the functional relevance of SIRT7 in HSC aging. Besides increased mitochondrial number and reduced stress resistance, SIRT7 deficient HSCs showed phenotypes characteristic of old HSCs, such as increased apoptosis during transplantation and a myeloid-biased differentiation. Accordingly, SIRT7 expression was reduced in aged HSCs and restoration of SIRT7 levels was sufficient to revert HSCs to a younger state.

In line with these findings, other sirtuins, such as the nuclear SIRT1 and mitochondrial SIRT3, have been shown to be essential for maintaining HSC youthfulness (4, 5). In contrast, however, in other tissues, sirtuins positively regulate mitochondrial function. For instance, SIRT7 deficient mice display multisytemic mitochondrial dysfunction due to destabilization of the GABP α/GABP β complex (6), while SIRT1 induces mitochondrial biogenesis (7). The findings of Mohrin et al. in HSCs reveal the heterogeneous effects that regulatory aging pathways exert in an organism’s health and longevity.

Biogerontology research has revealed that aging is a malleable process susceptible of alteration by manipulating conserved biological pathways. In addition to the hematopoietic system, age-associated changes in stem cells have been reported in other adult stem cell compartments, including muscle, bone, forebrain and germline (8, 9). Thus, decline of stem cell function with age due to intrinsic and extrinsic factors could potentially be reverted, indicating that rejuvenation strategies may one day slow down or even turn back the aging clock. Research based on heterochronic parabiosis has demonstrated that stem cell rejuvenation in different compartments is feasible through systemic environment rejuvenation (8, 10, 11). Strikingly, Mohrin et al. demonstrate that by targeting cell intrinsic deregulated programs, it is possible to reverse hematopoietic stem cell aging. This approach has recently been proven successful in muscle stem cells where inhibition of age-associated pathways restores muscle regeneration potential to a younger state (12). Scientific discoveries, such as the one reported in this issue of Science by Mohrin et al., expand our dream of achieving a healthy longevity that is as old as humankind.

Figure 1.

SIRT7 metabolic checkpoint regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging (HSCs). (A) In young HSCs, SIRT7 interacts with nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) repressing the transcription of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (mRPs) and translational factors (mTFs). This repression results in the suppression of mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration in HSCs. Young HSCs maintain a proper balance of quiescence, proliferation and differentiation between different blood cell types. (B) In old HSCs, SIRT7 expression is reduced, leading to the activation of mRPS and mTFs, increased mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial protein stress. As a consequence of these mitochondrial bursts, old HSCs exit quiescence, increase proliferation and are prone to a myeloid-biased differentiation.

REFERENCES

- 1.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh J, Lee YD, Wagers AJ. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Med. 2014;20:870–880. doi: 10.1038/nm.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. Metabolic Regulation in Pluripotent Stem Cells during Reprogramming and Self-Renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimmelé P, et al. Aging-like Phenotype and Defective Lineage Specification in SIRT1-Deleted Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:44–59. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown K, et al. SIRT3 Reverses Aging-Associated Degeneration. Cell Rep. 2013;3:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu D, et al. A SIRT7-Dependent Acetylation Switch of GABPβ1 Controls Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab. 2014;20:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers JT, et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conboy IM, et al. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433:760–764. doi: 10.1038/nature03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molofsky AV, et al. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006;443:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsimpardi L, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science. 2014;344:630–634. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha M, et al. Restoring Systemic GDF11 Levels Reverses Age-Related Dysfunction in Mouse Skeletal Muscle. Science. 2014;344:649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1251152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sousa-Victor P, et al. Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature. 2014;506:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]