Abstract

Background

Microbial conversion of biomass to fuels or chemicals is an attractive alternative for fossil-based fuels and chemicals. Thermophilic microorganisms have several operational advantages as a production host over mesophilic organisms, such as low cooling costs, reduced contamination risks and a process temperature matching that of commercial hydrolytic enzymes, enabling simultaneous saccharification and fermentation at higher efficiencies and with less enzymes. However, genetic tools for biotechnologically relevant thermophiles are still in their infancy. In this study we developed a markerless gene deletion method for the thermophile Bacillus smithii and we report the first metabolic engineering of this species as a potential platform organism.

Results

Clean deletions of the ldhL gene were made in two B. smithii strains (DSM 4216T and compost isolate ET 138) by homologous recombination. Whereas both wild-type strains produced mainly l-lactate, deletion of the ldhL gene blocked l-lactate production and caused impaired anaerobic growth and acid production. To facilitate the mutagenesis process, we established a counter-selection system for efficient plasmid removal based on lacZ-mediated X-gal toxicity. This counter-selection system was applied to construct a sporulation-deficient B. smithii ΔldhL ΔsigF mutant strain. Next, we demonstrated that the system can be used repetitively by creating B. smithii triple mutant strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA, from which also the gene encoding the α-subunit of the E1 component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is deleted. This triple mutant strain produced no acetate and is auxotrophic for acetate, indicating that pyruvate dehydrogenase is the major route from pyruvate to acetyl-CoA.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a markerless gene deletion method including a counter-selection system for thermophilic B. smithii, constituting the first report of metabolic engineering in this species. The described markerless gene deletion system paves the way for more extensive metabolic engineering of B. smithii. This enables the development of this species into a platform organism and provides tools for studying its metabolism, which appears to be different from its close relatives such as B. coagulans and other bacilli.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12934-015-0286-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bacillus smithii, Thermophile, Lactate dehydrogenase, Sporulation, Pyruvate dehydrogenase, Counter-selection system

Background

Microbial conversion of biomass to fuels such as ethanol or hydrogen, or to green chemical building blocks such as organic acids has gained increasing attention over the last decade [1, 2]. Thermophilic microorganisms have several advantages over mesophilic organisms for use as microbial production hosts. Fermentation at high temperatures lowers cooling costs and contamination risks and increases product and substrate solubility [3–5]. Moreover, the optimum temperature of moderate thermophiles matches that of commercial hydrolytic enzymes, enabling simultaneous saccharification and fermentation at higher efficiencies and with less enzymes compared to mesophilic bacteria [6].

Despite the aforementioned advantages of thermophiles, mesophilic model organisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are still preferred production organisms, as these are well-studied and genetic tools are available to enable their use as versatile platform organisms [7, 8]. Genetic tools for biotechnologically relevant thermophiles are recently emerging for different species, but most are still in their infancy or highly strain-specific. Several strictly and facultatively anaerobic thermophiles have been engineered for green chemical and fuel production, as has been reviewed recently [9, 10]. Most engineering efforts in thermophiles have so far been directed at ethanol production, but recently also examples for chemical production have been shown such as Thermoanaerobacterium aotearoense for lactate production [11], Bacillus licheniformis for 2,3-butanediol production [12], and Bacillus coagulans for d-lactate production [13, 14]. The development of genetic tools for thermophilic organisms is crucial to fully understand their metabolic versatility and to establish a thermophilic production platform for green chemical and fuel production. For industrial applications, markerless gene deletions should be made such that no antibiotic resistance genes or other scars are introduced into the target genome. This is especially important when working with thermophilic organisms as the number of available markers is limited, requiring re-use of the marker [9, 10].

Recently, we isolated a thermophilic Bacillus smithii strain capable of degrading C5 and C6 sugars at a wide range of temperatures and pHs [15] and demonstrated electrotransformation of several B. smithii strains with plasmid pNW33n. In the current study, we developed a clean gene deletion method and counter-selection system for this species and applied this to create multiple markerless gene deletions both in the previously isolated B. smithii ET 138 [15] and in the type strain B. smithii DSM 4216T.

Results

Construction of markerless ldhL deletion mutants

B. smithii ET 138 can be transformed with E. coli-Bacillus shuttle vector pNW33n with an efficiency of 5 × 103 colonies per µg DNA [15]. To obtain mutants in strain ET 138, we planned to use a protocol similar to that used for Geobacillus thermoglucosidans (recently renamed from G. thermoglucosidasius [16]), which applies pNW33n-derivatives as thermosensitive integration plasmid [17]. To create a markerless l-lactate dehydrogenase (ldhL) knockout strain from which the ldhL gene was entirely deleted, ~1,000 bp regions flanking the ldhL gene and including the start and stop codon were cloned and fused together in plasmid pNW33n. Double homologous recombination of this plasmid with the ET 138 chromosome will fuse the start and stop codons of the gene, thereby removing the entire gene in-frame without leaving any marker (Figure 1). B. smithii ET 138 was transformed with pWUR732 and colonies were transferred once at 55°C on LB2 plates containing chloramphenicol. Subsequent PCR analysis of 7 colonies already showed integration of the plasmid DNA without the temperature increase normally performed with thermosensitive integration systems [17]. A mixture of single crossover integrants via both upstream and downstream regions together with no-integration (either caused by replicating plasmids or randomly integrated plasmids) genotype was observed in one colony, one colony showed a mixture of downstream crossover and wild-type genotype, and five colonies showed no single crossovers but only wild-type genotype. Serial transfer of the colonies containing single crossovers in liquid medium combined with replica plating to identify double recombinants repeatedly resulted in only wild-type double crossover mutants. The mixed genotype persisted after several subculturings on plates containing 7 and 9 µg/mL chloramphenicol in an attempt to obtain pure genotypes. After four transfers, however, also a colony was found that contained a mixture of double crossover knockout genotype together with upstream single crossover and wild-type genotype. After this point, we added glycerol or acetate as carbon sources to allow for a metabolism with minimal impact of the ldhL deletion. After streaking this colony to an LB2 plate containing 10 g/L glycerol, colonies were obtained that had lost the wild-type genotype but contained a mixture of both single crossovers and a double crossover knockout genotypes. A pure double crossover knockout genotype was observed after two transfers on the more defined TVMY medium supplemented with acetate at 65°C, creating strain ET 138 ΔldhL (Figure 2a).

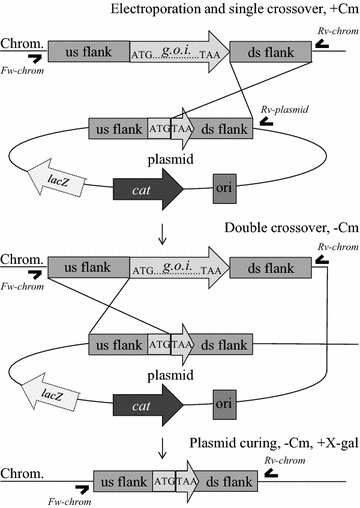

Figure 1.

Illustration of markerless knockout construction in B. smithii. a pNW33n-derived plasmid containing the 1,000 bp-flanking regions of a gene of interest (‘g.o.i.’) is introduced into the cell via electroporation, plated on LB2 containing chloramphenicol at 55°C and subjected to PCR analysis to check for single crossovers using primers ‘Fw-chrom’ and ‘Rv-plasmid’. Colonies containing single crossovers are transferred to plates without chloramphenicol, after which PCR screening is performed to check for double crossovers using primers ‘Fw-chrom’ and ‘Rv-chrom’. If the 2nd recombination occurs via the same flank as the 1st recombination, a wild-type genotype will be the result. If the 2nd recombination occurs via the other flank, this results in a knockout genotype. To delete the ldhL gene, only PCR screening was performed and no lacZ gene was present on the plasmid. For creating the sigF and pdhA mutants, the plasmid also contained the lacZ gene. In those cases, lacZ counter-selection was performed by plating an overnight culture on LB2 plates containing 100 µg/mL X-gal, resulting in toxic concentrations of the X-gal cleavage product in the presence of lacZ, resulting in small blue colonies still containing the plasmid (either replicating plasmid or inserted in the genome via single crossover) and white colonies that have cured the plasmid. g.o.i. gene of interest, cat chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, chrom. chromosome, us upstream, ds downstream, Cm chloramphenicol, primers are indicated with black hooks.

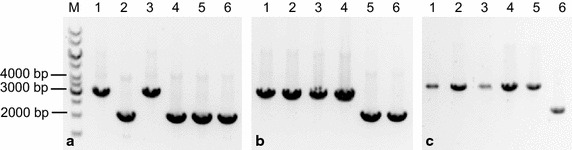

Figure 2.

Gel-electrophoresis of PCR products from amplified target genes ldhL (a), sigF (b) and pdhA (c). Order of strains in all three parts of the picture: M: Thermo Scientific 1 kb DNA ladder, 1 DSM 4216T wild-type, 2 DSM 4216T ΔldhL, 3 ET 138 wild-type, 4 ET 138 ΔldhL, 5 ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF, 6 ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA. The original gel pictures without cropping are provided in Additional files 1 (for a, b) and 2 (for c). a Amplification of the region 1,000 bp up- and downstream of the ldhL gene using primers BG 3663 and 3669. The wild-type genotype results in a product of 3,036 bp, whereas the complete deletion of the ldhL gene is confirmed by a shift of the product to 2,094 bp. b Amplification of the region 1,000 bp up- and downstream of the sigF gene using primers BG 3990 and 3991. The wild-type genotype results in a product of 3,040 bp, whereas the complete deletion of the sigF gene is confirmed by a shift of the product to 2278 bp. c Amplification of the region 1,000 bp up- and downstream of the pdhA gene using primers BG 4563 and 4564. The wild-type genotype results in a product of 3,390 bp, whereas the complete deletion of the pdhA gene is confirmed by a shift of the product to 2,280 bp.

Similar to strain ET 138, also type strain B. smithii DSM 4216T is transformable with pNW33n, with efficiencies of around 2x102 colonies per µg DNA [15]. After transformation of strain DSM 4216T with ldhL-knockout construct pWUR733 and transfer of colonies to a new plate at 55°C, PCR on 30 colonies showed mixtures of wild-type genotype and both single crossovers for all tested colonies. Contrary to what was observed with strain ET 138, several subculturings on TVMY supplemented with acetate at temperatures varying between 55 and 65°C did not result in a pure mutant genotype for derivatives of DSM 4216T. However, after the substrate was changed from acetate to lactate, a pure double-crossover knockout colony was obtained after two transfers, creating strain DSM 4216T ΔldhL (Figure 2a).

Establishment of a lacZ-counter-selection system

Purifying the mixtures of plasmid integrated into the B. smithii genome via single and double crossovers during the construction of the ldhL-mutant strains required laborious PCR-screening. To simplify the screening procedure, a counter-selection tool was desirable to select against plasmid presence. A lacZ-counter-selection method has been described for the Gram-negative mesophile Paracoccus denitrificans, which is based on toxicity of high X-gal concentrations in the presence of β-galactosidase activity encoded by a lacZ-gene on the integration plasmid [18]. In the genome sequence of B. smithii ET 138 (unpublished data) no lacZ gene could be identified and the strain did not form blue colonies on plates containing X-gal. The lacZ gene from B. coagulans under control of the B. coagulans pta-promoter [14] was cloned into pNW33n, creating plasmid pWUR734. Introduction of pWUR734 into B. smithii ET 138 resulted in blue colonies in the presence of 25 mg/L X-gal. When B. smithii ET 138 harbouring pWUR734 was grown in the presence of 100 mg/L X-gal, the blue colonies were significantly smaller than on 25 mg/L, indicating toxicity of the X-gal cleavage product at high X-gal-concentrations (Additional file 3). To test the lacZ-counter-selection system, we chose sigF (spoIIAC) as the first knockout target gene, which is involved in the onset of Bacillus sporulation [19] (Figure 1). Transformation of strain ET 138 ΔldhL with sigF-knockout vector pWUR735 containing the ~1,000 bp flanking regions of sigF yielded only blue and no white colonies, indicating functional expression of the B. coagulanspta::lacZ construct. Colony PCR on 8 colonies showed a mixture of single crossovers, wild-type and double-crossover knockout genotypes for six colonies and no single crossover but only double-crossover knockout and wild-type genotypes for two colonies. The latter two colonies, however, failed to grow after transfer to new LB2 plates. To obtain pure knockout strains, the counter-selection was applied by growing the colonies containing the mixed genotype of single and double crossovers overnight in 10 mL LB2 at 55°C, after which dilution series were plated on LB2 supplemented with 100 mg/L X-gal. A mix of large white (1–3 mm) and small blue (≤1 mm) colonies was obtained for all six cultures (Additional file 3). Colony PCR on three white colonies from one of the cultures showed the presence of one pure knockout, one pure wild-type and one mix of wild-type and single-crossover genotypes. The colony showing the pure knockout genotype was inoculated into liquid LB2, after which DNA was isolated and PCR analysis confirmed the knockout genotype and absence of plasmid, creating strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF (Figure 2b).

Construction of markerless triple mutant

To evaluate whether the lacZ-counter-selection method can be used repeatedly to delete multiple genes and to evaluate acetate production pathways in B. smithii ET 138, the α-subunit of the E1 component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex pdhA was targeted for deletion in strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF using the lacZ-counter-selection system. Based on genome analysis, pyruvate dehydrogenase appears to be the only route to acetyl-CoA in B. smithii (unpublished data). Therefore, the mutant strain was expected to be dependent on acetate to form acetyl-CoA and the medium was supplemented with acetate at all times after transformation. After transformation with pdhA-knockout vector pWUR737 containing the ~1,000 bp flanking regions of pdhA, cells were plated on TVMY supplemented with acetate and chloramphenicol. PCR on 15 colonies showed 13 colonies with a mixture of wild-type genotype together with both single crossovers, one colony with a mixture of wild-type and downstream crossover and 1 colony with a pure downstream crossover. After one transfer of the downstream crossover colony on LB2 medium supplemented with acetate without chloramphenicol, a colony was picked showing a mixture of downstream crossover, wild-type and double crossover knockout genotypes. This colony was subjected to the counter-selection protocol by plating on 100 mg/L X-gal after overnight growth in liquid LB2, resulting in a mixture of small blue and large white colonies. From the 32 white colonies tested in PCR, 12 still showed single crossovers, 16 returned to wild-type and 4 showed a clean double crossover knockout genotype, creating triple mutant ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA (Figure 2c).

Confirmation of sporulation deficiency

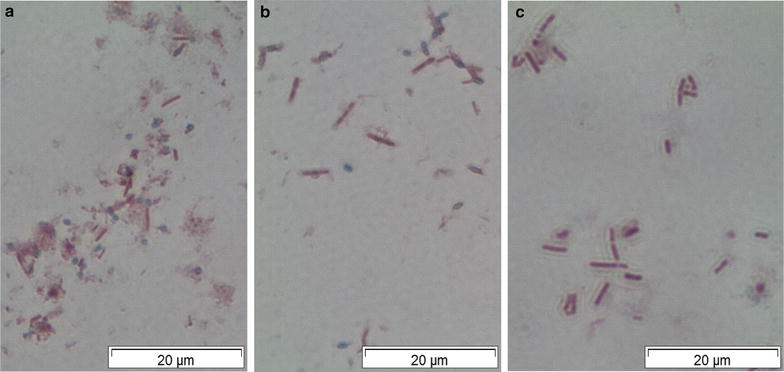

To confirm that strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF was unable to form spores, a Schaeffer-Fulton staining was performed (Figure 3). In the wild-type and the ldhL-mutant (Figure 3a, b) many spores were observed as indicated by the presence of green spheres, whereas no spores were observed in the ldhL-sigF-double mutant (Figure 3c). Pasteurisation of cultures of the wild-type and the ΔldhL-strain resulted in colony counts of >5 × 105 and 3 × 105 per mL of cells, respectively. As expected, no colonies were observed after Pasteurisation of a culture of the ΔldhL ΔsigF double mutant, while colony counts for the control treatment were >5 × 105 per mL of cells for all three strains. Both assays confirm that the removal of the sigF gene results in a sporulation-deficient phenotype.

Figure 3.

Schaeffer-Fulton staining on ET 138 wild-type and mutants. Cultures used were grown aerobically overnight in LB2 medium at 55°C and subsequently kept at room temperature for 24 h, after which the staining was performed. Pink-stained cells indicate intact cells, whereas spores are green–blue. a strain ET 138 wild-type, in which sporulation is observed. b strain ET 138 ΔldhL, in which sporulation is observed. c Strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF, where no sporulation is observed due to removal of the sigF gene.

Growth and production characteristics of mutant strains

To evaluate growth and fermentation characteristics of the mutant strains, both strains ET 138 and DSM 4216T and all derived mutants were grown in tubes for 24 h under micro-aerobic conditions (Table 1). Whereas both ET 138 and DSM 4216T wild-type strains produced mainly l-lactate (±95.5% of total products), the deletion of ldhL reduced l-lactate production to values around or below the detection limit, as shown by HPLC analysis combined with d- and l-lactate-specific enzyme assays (Table 1). For both strains, the main product shifted from l-lactate to acetate, with minor amounts of d-lactate, malate and succinate and increased concentrations of pyruvate compared to the wild-types. Both the OD600 and the final product titre of the mutants were about half that of the wild-types. Strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF did not show significant differences compared to strain ET 138 ΔldhL (Table 1). When the volume was increased from 25 to 40 mL in 50 mL tubes to further decrease the amount of oxygen present, the mutant strains showed even further reduced growth and production compared to the wild-type (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in 1 L pH controlled reactors (Additional file 4). Complementation of strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF with its native ldhL gene and promoter expressed from pNW33n restored growth and l-lactate production to around wild-type levels (Table 1). Triple mutant ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA was unable to grow without acetate supplementation and produced mainly d-lactate and pyruvate. In this strain, very minor amounts of l-lactate (0.39 ± 0.02 mM) were observed. The final OD600 of this strain was on average comparable to the single and double mutant, but it showed less variation (Table 1).

Table 1.

HPLC analysis of B. smithii ET 138 and DSM 4216T wild-type and mutant strains

| Strain | Products (mM) and measurement method | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic | HPLC | |||||||

| l-lac | d-lac | Lac | Ace | Pyr | Mal | Suc | OD600 | |

| DSM 4216 wild-type | 15.85 ± 2.22 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 20.67 ± 1.25 | 9.12 ± 0.49 | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | 0.785 ± 0.209 |

| DSM 4216 ΔldhL | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 4.11 ± 0.86 | 4.95 ± 3.35 | 12.40 ± 3.16 | 1.48 ± 1.14 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.57 ± 0.22 | 0.466 ± 0.057 |

| ET 138 wild-type | 20.55 ± 4.09 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 26.18 ± 7.66 | 8.25 ± 2.59 | 0.78 ± 0.31 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.61 ± 0.16 | 1.036 ± 0.136 |

| ET 138 ΔldhL | 0.08 ± 0.09 | 1.08 ± 0.32 | 1.73 ± 0.48 | 14.33 ± 5.54 | 0.76 ± 0.82 | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.72 ± 0.22 | 0.581 ± 0.289 |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.20 | 1.58 ± 0.62 | 10.97 ± 2.13 | 0.70 ± 0.41 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.672 ± 0.102 |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA a | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 11.17 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ± 2.07 | −3.19a ± 1.24 | 8.26 ± 0.82 | 1.12 ± 0.14 | 1.85 ± 0.37 | 0.696 ± 0.119 |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF + pWUR736 | 18.13 ± 3.82 | 1.11 ± 0.40 | 18.99 ± 5.19 | 7.32 ± 1.33 | 0.24 ± 0.16 | 0.08 ± 0.18 | 0.39 ± 0.17 | 0.831 ± 0.200 |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF + pNW33n | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 2.57 ± 1.30 | 3.17 ± 1.13 | 10.14 ± 0.91 | 0.94 ± 0.53 | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.535 ± 0.062 |

| ET 138 wild-type + pNW33n | 22.12 ± 3.69 | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 21.42 ± 1.51 | 5.63 ± 1.15 | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.12 | 0.34 ± 0.14 | 0.849 ± 0.076 |

Strains were grown in 25 mL TVMY supplemented with 10 g/L glucose in 50 mL Greiner tubes at 55°C for 24 h after transfer from a 10 mL-overnight culture. d- and l-lactate were distinguished via enzymatic assays, for which the lowest detection limit was 0.04 mM. The values shown are the results of three to fourteen independent experiments; numbers in italics are standard deviations.

l -lac l-lactate, d -lac d-lactate, Ace acetate, Pyr pyruvate, Mal malate, Suc succinate.

aThese cultures were supplemented with 3 g/L ammonium acetate.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an integration and counter-selection system for markerless and consecutive gene deletion in thermophilic B. smithii. As l-lactate is the main fermentation product of B. smithii, the ldhL-gene was selected as the first knockout target in order to use this bacterium for the production of other products. Wang et al. reported a laborious screening procedure when constructing a B. coagulans ΔldhL strain and indicated that only 1 in 5,000 colonies showed a knockout genotype after double crossover [13]. We observed a similar bias in B. smithii for the second crossover to result only in wild-type revertants. Furthermore, in single colonies we observed mixtures of either upstream or downstream single crossovers, wild-type and double crossover knockout genotype, even after several transfers targeted at purifying the colony. These mixed genotypes were not only observed for the ldhL deletion, but also for the sigF and pdhA deletions. For E. coli, such mixed genotypes have been described to occur during recombineering with linear DNA fragments, where it has been attributed to polyploidy, i.e. the existence of multiple chromosomes [20]. The copy number of the genome of our organism is currently unknown, but in general this number is likely to be higher when cells are grown in rich medium compared to minimal medium [20]. Transformation attempts with B. smithii grown on minimal medium were not successful (data not shown), but when cells were grown on minimal medium after crossovers had occurred, the purification of pure genotypes was relatively fast and easy. Switching to minimal medium to overcome mixed genotype issues might be a useful approach for other species as well.

In other thermophilic Bacilli, integration events were reported after the growth temperature had been increased [17, 21]. Integration of the pNW33n-derived knockout plasmids in B. smithii without increasing the temperature indicates either a highly efficient recombination machinery, or plasmid instability already at 55°C, although this temperature is regarded as permissive for pNW33n [17]. In both B. smithii strains, we observed very stable plasmid integration into the genome via single crossover recombination in colonies grown on plates without antibiotic pressure. As this integrational stability hampered purification of pure double crossover knockouts, a counter-selection method was developed to select against plasmid presence. Most frequently used counter-selection systems are based on either auxotrophy or antibiotic resistance. The lacZ-system is fundamentally different in enabling clean gene deletions and re-use of the marker without inducing auxotrophies, as has been demonstrated in the mesophilic α-proteobacterium Paracoccus denitrificans [18]. The system can readily be used without making any prior gene deletions if the target strain does not possess β-glycosidase activity, as is the case in B. smithii. The system is based on the formation of toxic concentrations of inodxyl derivatives such as 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indol, which is the cleavage product of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). Recently, indoxyl derivatives were shown to inhibit the growth of a wide variety of species growing at different temperatures, indicating that this system might be more widely applicable [22].

The lacZ-counter selection system considerably simplified the purification of single genotypes and enabled rapid and clean deletion of the sigF gene of ET 138 ΔldhL to create a sporulation-deficient strain. The system can be used repetitively to make multiple sequential deletions in the same strain as shown by the generated triple mutant ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA. For both the sigF and the pdhA deletion, around 33% of the tested colonies were false positive after counter-selection, as they were white while still having a single crossover, which might be due to spontaneous disruption of the lacZ coding sequence or its promoter. Even with 33% false-positive white colonies, the screening for mutants is significantly simplified when using the lacZ-counter-selection system. A drawback of the system is that it does not force the double crossover in the direction of the knockout and can result in wild-type revertants. Whenever possible, cultivation conditions should be chosen such that the knockout cells will not have a large disadvantage over the wild-type cells. During this study, culturing in liquid medium resulted only in wild-type revertants, whereas knockouts were successfully obtained when the cultures were kept on plates. Supplementation of the plates with the gluconeogenic substrates acetate or lactate might have further reduced the disadvantage of knockouts over wild-types.

Removal of the sigF gene from B. smithii ET 138 resulted in a sporulation-deficient strain. Sporulation deficiency is desired in industrial settings both for practical and safety reasons. B. smithii was shown to have highly thermo-resistant spores [23, 24] and was found to be the most dominant species together with Geobacillus pallidus (recently renamed to Aeribacillus pallidus [16]) as highly thermostable spores in food. Both species were found to be non-cytotoxic [23]. The sigF-gene has been targeted successfully to create sporulation-deficient strains in several other Bacilli as well as in Clostridia, such as in B. coagulans [14], B. licheniformis [25, 26], B. subtilis [19] and Clostridium acetobutylicum [27].

Removal of the ldhL-gene from B. smithii ET 138 and DSM 4216T eliminated l-lactate production in both strains to values around or below the detection limit, which is similar to an ldhL-knockout of B. coagulans [13], a close relative of B. smithii. A lactate racemase was not found in the ET 138 genome, but the methylglyoxal pathway was annotated towards both d- and l-lactate (unpublished data) and this pathway is most likely the origin of the trace amounts of lactate observed in triple mutant ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA. Products such as acetoin, 2,3-butanediol, formate and ethanol have not been detected in any of the B. smithii mutant strains, while these were observed in B. coagulans ΔldhL [13]. The absence of these products is in line with the absence of the acetolactate decarboxylase and pyruvate-formate lyase genes from the B. smithii genomes (unpublished data). The B. smithii ldhL-mutants produced mainly acetate and some d-lactate and showed reduced growth and acid production under micro-aerobic conditions, which was restored by plasmid-based complementation in strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF. The deficiency in anaerobic capacities is likely to be caused by the redox imbalance that results from the elimination of its main NAD+-regeneration pathway and the apparent lack of an alternative NAD+-regeneration pathway, such as that to 2,3-butanediol. The lack of these pathways potentially makes B. smithii an interesting platform organism as only the ldhL gene needs to be removed in order to eliminate production, after which the desired product pathways can be inserted.

Acetate was the main fermentation product of the B. smithii strains lacking the ldhL gene, but the standard pathway to acetate via acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase as well as a pyruvate-formate lyase gene are absent in the genomes of both strains ET 138 and DSM 4216T (unpublished data). To remove acetate production, the pdhA gene encoding the α-subunit of the E1 component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex was removed from strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF. The resulting strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA did not produce acetate and was unable to grow without acetate supplementation. This implies that pyruvate dehydrogenase is the main enzyme responsible for pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, which is in line with the absence of a pfl gene. Acetate utilization was previously suggested as a rescue pathway for redox balance in Lactococcus lactis ΔldhL [28]. We tested acetate supplementation of strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF but this did not improve growth or production (data not shown).

Conclusion

In this study, we established a clean gene deletion system for B. smithii using lacZ counter-selection. We constructed ldhL mutants in the type strain B. smithii DSM 4216T and compost isolate strain ET 138. In the latter strain, triple mutant ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA was constructed, which does not produce l-lactate and acetate and is no longer capable of forming spores. Although further studies and modifications are needed to restore anaerobic growth and production capacities, the lacZ-counter-selection system combined with mutant-specific culturing strategies provides a tool for the construction of markerless gene deletions in thermophilic B. smithii. This enables the development of this species into a platform organism and provides tools for studying its metabolism, which appears to be different from its close relatives such as B. coagulans and other Bacilli.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. All B. smithii strains were routinely cultured at 55°C unless stated otherwise. E. coli DH5α was grown at 37°C. For growth experiments with strain ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA, 3 g/L ammonium acetate was added to all media at all times. For all tube and plate cultures, carbon substrates were used in a concentration of 10 g/L unless stated otherwise. Substrates and acetate were added separately as 50% autoclaved solutions after autoclavation of the medium. For plates, 5 g/L Gelrite (Roth) was added. Unless indicated otherwise, chloramphenicol was added in concentrations of 25 µg/mL for E. coli and 7 µg/mL for B. smithii.

Table 2.

B. smithii strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference/origin |

|---|---|---|

| DSM 4216T | Wild-type, type strain of the species | DSMZ |

| DSM 4216T ΔldhL | DSM 4216T with clean ldhL-deletion | This study |

| ET 138 | Wild-type, natural isolate | [15] |

| ET 138 ΔldhL | ET 138 with clean ldhL-deletion | This study |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF | ET 138 ΔldhL with clean sigF-deletion | This study |

| ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA | ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF with clean pdhA-deletion | This study |

DSMZ Deutsche Sammlung von Microorganismen und Zellkulturen, Germany.

Thermophile Vitamin Medium with Yeast extract (TVMY) contained per L: 8.37 g MOPS; 0.5 g yeast extract (Roth), 100 mL 10× concentrated Eight Salt Solution (ESS), 1 mL filter sterile 1,000× concentrated vitamin solution, and 1 mL filter sterile 1,000× concentrated metal mix. ESS contained per L: 2.3 g K2HPO4; 5.1 g NH4Cl; 50 g NaCl; 14.7 g Na2SO4; 0.8 g NaHCO3; 2.5 g KCl; 18.7 g MgCl2.6H2O; 4.1 g CaCl2.2H2O). 1,000× concentrated metal mix contained per L: 16.0 g MnCl2.6H2O; 1.0 g ZnSO4; 2.0 g H3BO3; 0.1 g CuSO4.5H2O; 0.1 g Na2MoO4.2H20; 1.0 g CoCl2.6H2O; 7.0 g FeSO4.7H2O. 1,000× concentrated vitamin mix contained per L: 0.1 g thiamine; 0.1 g riboflavin; 0.5 g nicotinic acid; 0.1 g panthothenic acid; 0.5 g pyridoxamine, HCl; 0.5 g pyridoxal, HCl; 0.1 g D-biotin; 0.1 g folic acid; 0.1 g p-aminobenzoic acid; 0.1 g cobalamin. The pH of TVMY was set to 6.94 at room temperature and the medium was autoclaved for 20 min at 121°C, after which vitamin solution, metal mix and substrate were added.

LB2 medium contained per L: 10 g tryptone (Oxoid), 5 g yeast extract (Roth), 100 mL ESS. The pH was set to 6.95 at room temperature and the medium was autoclaved for 20 min at 121°C. For all mutant strains, vitamins and metals as described above for TVMY were also added to LB2.

To evaluate product profiles and growth, cells were inoculated from glycerol stock into 10 mL TVMY supplemented with 10 g/L glucose in a 50 mL Greiner tube and grown overnight at 55°C and 150 rpm. Next morning, 250 µL cells was transferred to 25 mL of the same medium in 50 mL Greiner tubes and incubated at 55°C and 150 rpm for 24 h, after which OD600 was measured and fermentation products were analysed.

Plasmid construction

Plasmids and primers used in this study are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Genomic DNA from B. smithii strains was isolated using the MasterPure™ Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre). E. coli DH5α heat shock transformation was performed according to standard procedures [29]. All restriction enzymes and polymerases were obtained from Thermo Scientific. PCR products were gel-purified from a 0.8% agarose gel using the Zymoclean™ Gel DNA Recovery Kit.

Table 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference/origin |

|---|---|---|

| pNW33n | E. coli-Bacillus shuttle vector, cloning vector, CmR | BGSC |

| pWUR732 | ldhL-KO vector for ET138: pNW33n + ldhL-flanks | This study |

| pWUR733 | ldhL-KO vector for DSM 4216: pNW33n + ldhL-flanks | This study |

| pWUR734 | pNW33n + B. coagulans Ppta-lacZ | [14]; this study |

| pWUR735 | sigF-KO vector for ET138: pWUR734 + ET 138 sigF-flanks | This study |

| pWUR736 | ldhL-restoration vector for ET138: pNW33n + ldhL-gene from ET 138 under its native promoter (525 bp us of ldhL) | This study |

| pWUR737 | pdhA-KO vector for ET138: pWUR734 + ET 138 pdhA -flanks | This study |

Cm R chloramphenicol resistance gene, KO knockout, BGSC Bacillus Genetic Stock Centre, USA, us upstream, bp base pairs.

Table 4.

Primers used in this study

| BG nr | Sequence 5′–3′ | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 3464 | AACTCTCCGTCGCTATTGTAACCA | Check plasmid presence |

| 3465 | TATGCGTGCAACGGAAGTGAC | Check plasmid presence |

| 3633 | GCCGTCGACCATTTGCAGTAGGTCTCGATC | ldhL-us-Fw |

| 3636 | GCCGAATTCTAGGTCACCAAAGACGAAATTG | ldhL-ds-Rv |

| 3637 | GCTCCCTTTGTATGGTCGTTTACATAATAAGAAACTCCTTTCGTCATTTC | ldhL-us-Rv |

| 3638 | GAAATGACGAAAGGAGTTTCTTATTATGTAAACGACCATACAAAGGGAGC | ldhL-ds-Fw |

| 3664 | AGGGCTCGCCTTTGGGAAG | Int. check, in plasmid |

| 3663 | ATCGCGTGAAATGTTCTAATGG | Int. check ldhL on chr.-Fw |

| 3669 | AACCGATGCCGTTGATTAAAG | Int. check ldhL on chr.-Rv |

| 3887 | GCCGAGCTCTTGCCGGAATTCTTTCAC | pta-lacZ-Fw |

| 3888 | GCCTCATGACTATTTTTCAATTACCTGCAAAATTTTC | pta-lacZ-Rv |

| 3971 | GCCGAATTCAGCTAATCTTGTTGACGGTTTTC | sigF-ds-Fw |

| 3972 | GTAACTAAGGAGTCGTGCCTTAACGATTCATGTGCTTTTTTTTG | sigF-ds-Rv |

| 3973 | CAAAAAAAAGCACATGAATCGTTAAGGCACGACTCCTTAGTTAC | sigF-us-Fw |

| 3974 | GCCGTCGACCTCTGATTTAGAAGATGGAGGTTTT | sigF-us-Rv |

| 3990 | CGCCTATTCTTTTCGCTAAAATCGG | Int. check sigF on chr.-Fw |

| 3991 | ATAAGCTGCAGAGGGATATACAC | Int. check sigF on chr.-Rv |

| 4534 | GCCTCTAGAATTGGTCATTTGATTAGA | ET 138 ldhL + prom.-Fw |

| 4535 | GCCAAGCTTTTAAGAAAGTACTTTATT | ET 138 ldhL + prom.-Rv |

| 4522 | GCCGAATTCGAGGTACATAGCCCGGAATC | pdhA-us-Fw |

| 4523 | GTCATTTGCGGCATGGCTTACATTCGTGTCACCTCTTCCTTTC | pdhA-us-Rv |

| 4524 | GAAAGGAAGAGGTGACACGAATGTAAGCCATGCCGCAAATGAC | pdhA-ds-Fw |

| 4525 | GCCGTCGACCATCCTCATAACGGCCATCC | pdhA-ds-Rv |

| 4563 | GTTTCACATACCATTTAACGATTT | Int. check pdhc on chr.-Rv |

| 4564 | GTCAATAGGTGCAAATGGATTTTC | Int. check pdhc on chr.-Fw |

us upstream flanking region, ds downstream flanking region, Fw forward primer, Rv reverse primer, Int. integration, chr. chromosome, prom. promoter.

For the construction of ET 138 ldhL-knockout vector pWUR732, the flanking regions of the ldhL gene were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA using primers BG3633 and BG3637 (upstream, 923 bp) and BG3638 and BG3636 (downstream, 928 bp) using Phusion polymerase. DSM 4216TldhL-knockout vector pWUR733 was created using the same primers, resulting in a 913 bp upstream region and 935 downstream. After gel-purification, an overlap extension PCR was performed in which the upstream and downstream region were fused using primers BG3633 and BG3636, making use of the complementary overhang in primers BG3637 and BG3638. The resulting PCR product was again gel-purified and subsequently cut with EcoRI and SalI using the restriction sites included in primers BG3633 and BG3636, as was plasmid pNW33n. After restriction, the fusion product and pNW33n were ligated using T4 ligase (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature and transformed to heat shock competent E. coli DH5α.

To create lacZ-containing plasmid pWUR734, primers BG3887 and BG3888 were used to generate the B. coagulans Ppta-lacZ promoter-gene fusion fragment by PCR using plasmid pPTA-LAC as template [14]. The resulting fragment was cloned into pNW33n using SacI and BspHI and transformed to heat shock competent E. coli DH5α.

The ET 138 sigF flanking regions fragments of the knockout-plasmid pWUR735 were generated by using primers BG3971 and BG3972 (downstream, 970 bp) and BG3973 and BG3974 (upstream, 976 bp). The flanks were fused by PCR using primers BG3971 and BG3974, cloned into pWUR734 using EcoRI and SalI and transformed to heat shock competent E. coli DH5α. Plasmid pWUR737 containing the pdhA flanks in pWUR734 was constructed in a similar manner, using primers BG4522 and BG4523 to generate the pdhA upstream flank (1011 bp) and BG4524 and BG4525 to generate the pdhA downstream flank (1037 bp) by PCR. The flanks were fused by PCR using primers BG4522 and 4525 and cloned into pWUR737 using EcoRI and SalI.

For construction of ET 138 ldhL-complementation plasmid pWUR736, the ldhL gene with its native promotor (until 525 bp upstream of the gene) was amplified from the ET 138 genome using primers BG4534 and BG4535. The fragment was cloned into pNW33n using HindIII and XbaI.

Transformed E. coli DH5α colonies were picked and inoculated into 5 mL LB containing 25 µg/mL chloramphenicol, after which plasmids were isolated using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Scientific) and the integrity of the cloned fragments was confirmed by DNA sequencing (GATC, Germany). Plasmids for transforming ET 138 and DSM 4216T were extracted from DH5α via maxiprep isolation (Genomed Jetstar 2.0).

Competent cell preparation and electroporation of B. smithii

B. smithii was transformed by electroporation as described previously [15]. In brief, B. smithii cells were grown overnight at 55°C in 10 mL LB2 in a 50 mL Greiner tube and next morning diluted to an OD600 of 0.08 in 100 mL LB2 in a 500 mL baffled Erlenmeyer flask (DSM 4216T) or 1 L bottle (ET 138). Cells were grown to an OD600 between 0.45 and 0.65 and made competent as described previously [30]. Electroporation was performed applying settings of 2.0 kV, 25 µF and 400 Ω in a 2 mm cuvette for ET 138 and 1.5 kV, 25 µF and 600 Ω in a 1 mm cuvette for DSM4216T (ECM 630 electroporator, GeneTronics Inc.). 2–5 µg plasmid DNA was added to the cells for electroporation and LB2 medium was used for recovery at 52°C for 3 h. After overnight growth on LB2 plates containing 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and in the case of lacZ-containing plasmids also 20 µg/mL X-gal at 52°C, several colonies were streaked to a fresh plate and grown overnight at 55°C, after which colony PCR was performed to confirm the presence of the plasmid and check for integration.

B. smithii colony PCR

Colony PCR on B. smithii was performed using the InstaGene Matrix protocol (BioRad) with several modifications: colonies were picked and resuspended in 200 µL MQ water in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was removed, 100 µL InstaGene Matrix was added to the pellet and this was incubated at 55°C for 30 min. After this, the mixtures were vortexed at high speed for 10 s and incubated at 99°C in a heat block (Eppendorf) for 8 min, vortexed again for 10 s and centrifuged at 13200 for 3 min. Subsequently, 10 µL of the resulting supernatant was used per 25 µL PCR reaction and the remainder was stored at −20°C for later use.

Construction of B. smithii ET 138 and DSM 4216TldhL mutants

B. smithii ET 138 was made competent and electroporated with pWUR732. After transformation, colonies were subjected to colony PCR using primers BG3663 and BG3669 to distinguish double crossover wild-type and knockout genotypes, BG3664 and BG3669 to check chromosomal integration of the plasmid and BG3464 and BG3465 to check plasmid presence. A colony showing both upstream and downstream integration as well as wild-type genotype was picked and streaked to a fresh LB2 plate supplemented with 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and grown overnight at 55°C, which was repeated one more time at 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and then twice at 9 µg/mL chloramphenicol. From the last plate, a colony was picked that showed both wild-type and double-crossover knockout genome, as well as a single crossover via the upstream region. After overnight growth on LB2 supplemented with 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and 1% glycerol at 55°C, a colony was picked that did no longer show the wild-type genotype. This colony was transferred twice on TVMY supplemented with 50 mM ammonium acetate at 65°C, resulting in a pure knockout genotype. Genomic DNA isolation was performed on liquid cultures grown overnight in TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate to confirm the knockout genotype and lack of plasmid. The PCR product from primers BG3663 and BG3669 was purified (Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator) to confirm correct deletion of the gene by sequencing.

B. smithii DSM4216T was made competent and transformed with pWUR733, colonies were streaked to a new LB2 plate with 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and checked for integrations as described for B. smithii ET 138. A colony showing wild-type genotype as well as both upstream and downstream integration was picked and streaked to a fresh LB2 plate supplemented with 9 µg/mL chloramphenicol and grown overnight at 55°C. Subsequently, it was transferred 3 more times on the same medium at 55°C and once at 65°C, after which 1 transfer was performed on LB2 containing 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol and 1% (v/v) glycerol at 55°C. Next, the colony was transferred several times on TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate at 55°C and 65°C. During the whole procedure, colony PCR using the above-mentioned primers was performed and only colonies showing single crossover (combined with wild-type genotype) were transferred. Subsequently, a colony showing double crossover knockout genotype mixed with wild-type and single crossovers was purified by transferring to TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate 5 more times at 60°C and then 2 times on TVMY containing 50 mM lactate. Genomic DNA isolation was performed on liquid cultures grown overnight in TVMY containing 50 mM lactate to confirm the knockout genotype and lack of plasmid. The PCR product from primers BG3663 and BG3669 was purified (Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator) to confirm correct deletion of the gene by sequencing.

Construction of B. smithii ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF mutant using lacZ counter-selection

After transformation of B. smithii ET 138 ΔldhL with plasmid pWUR735, blue colonies were transferred to new LB2 plates supplemented with 7 µg/mL chloramphenicol twice at 55°C. Subsequently, colony PCR was performed using primers BG3990 and BG3991 to distinguish double crossover wild-type and knockout genotypes, and primers BG3990 and BG3664 to check chromosomal integration of the plasmid and BG3464 and BG3465 to check plasmid presence. Several colonies showing a mixture of single crossovers, wild-type and double-crossover knockout genotype were transferred to 10 mL LB2 in 50 mL tubes and grown overnight at 55°C, after which dilution series were plated on LB2 supplemented with 100 µg/mL X-gal. After overnight growth, white colonies were picked and transferred twice for overnight growth at 55°C on LB2 plates, after which colony PCR was performed to distinguish wild-type from double-crossover knockout genotype. Genomic DNA isolation was performed on liquid culture grown overnight in LB2 to confirm the knockout genotype and lack of plasmid. The resulting PCR product was purified (Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator) to confirm correct deletion of the gene by sequencing and glycerol stocks were made.

Construction of B. smithii ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF ΔpdhA mutant using lacZ counter-selection

B. smithii ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF was transformed with plasmid pWUR737 and recovery and plating was performed at 52°C on TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate, 7 µg/mL Cm and 20 µg/mL X-gal. Next day, blue colonies were streaked to new plates containing the same medium without X-gal and grown overnight, after which colony PCR was performed using primers BG4563 and BG4564 to distinguish double crossover wild-type and knockout genotypes and BG4564 and BG3664 to check chromosomal integration of the plasmid. Several colonies showing either single crossover and/or double crossover were transferred to fresh TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate plates containing antibiotics and grown overnight at 52°C, after which the same colony PCR was performed on the new colonies. One colony that showed only downstream crossover, whereas the others showed only upstream crossover, did not grow any further on TVMY containing 50 mM ammonium acetate and thus was transferred to LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate plates without antibiotics and subjected again to colony PCR after overnight growth. One colony showing a strong double crossover knockout band was transferred to LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate and grown overnight, after which it was inoculated into 10 mL liquid LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate in a 50 mL tube and grown overnight at 55°C and 150 rpm. Subsequently, dilution series were plated on LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate supplemented with 100 µg/mL X-gal. After overnight growth, white colonies were streaked to a new plate LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate and subjected to colony PCR. Several colonies showing pure knockout genotype were inoculated into 10 mL LB2 containing 50 mM ammonium acetate and grown overnight. Genomic DNA isolation was performed on liquid cultures grown overnight in LB2 to confirm the knockout genotype and lack of plasmid, after which the resulting PCR product was purified (Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator) to confirm correct deletion of the gene by sequencing.

Sporulation assays

For the Schaeffer-Fulton staining [31], B. smithii strains ET 138 wild-type, ET 138 ΔldhL and ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF were grown aerobically overnight in LB2 medium at 55°C and subsequently kept at room temperature for 24 h, after which a droplet of the cell culture was added to a microscopy slide and allowed to air-dry. The sample was heat-fixed above a gas flame and covered with a piece of absorbance paper, after which the slide was flooded with 50 g/L malachite green (4-[(4-dimethylaminophenyl)phenyl-methyl]-N,N-dimethylaniline) and heated to steam twice. The absorbance paper was removed and the slide was washed with tap water, after which it was flooded with 25 g/L safranin for 30 s, washed with tap water, dried with paper and evaluated under the microscope (Carl Zeiss Primo Star 1000x magnification with Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions Camera and analySIS 5.0 imaging software).

For the pasteurization assay, strains ET 138 wild-type, ET 138 ΔldhL and ET 138 ΔldhL ΔsigF were grown for 24 h in 10 mL LB2 in a 50 mL Greiner tube. 1 mL culture was transferred to a 1.5 mL reaction tube in duplicate, of which one tube was incubated at 60°C for 45 min as a control and one at 85°C for 45 min. After this, a 100× dilution was plated on LB2 and incubated overnight at 55°C, after which colonies were counted.

Analytical methods

Sugar and fermentation products were quantified using a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Thermo) equipped with a UV1000 detector operating on 210 nm and a RI-150 40°C refraction index detector and containing a Shodex RSpak KC-811cation-exchange column. The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM H2SO4 and the column was operated at 0.8 mL/min and 80°C. All samples were diluted 1:1 with 10 mM DMSO in 0.04 N H2SO4. l-lactate and d-lactate kits from Megazyme (K-LATE and K-DATE) were used to distinguish between l-lactate and d-lactate according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Authors’ contributions

EFB designed, executed and analysed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. AHPvdW participated in the design of the experiments, performed the experimental and analytical part of the growth experiments and revised the manuscript. LvdV constructed and analysed the sigF mutant, designed and performed the sporulation assays and was involved in revision of the manuscript. JvdO, WMdV and RvK participated in the design and co-ordination of the study and in revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sjuul Hegger and Martinus J.A. Daas for technical assistance, Corbion (Gorinchem, NL) for kindly providing plasmid Ppta-lacZ [14] and Dr. Ron Winkler from Dutch Technology Foundation STW for his involvement in an earlier phase of this work. This work was financially supported by Corbion.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. RvK is employed by the commercial company Corbion (Gorinchem, The Netherlands).

Additional files

This file shows the original gel for Figure 2A and B. It is the same gel as in Figure C/additional file 2, but with a shorter exposure time.

This file shows the original gel for Figure 2 C. It is the same gel as in Figure A-B/additional file 1, but with a longer exposure time.

B. smithii ΔldhL-ΔsigF after counter-selection on plates containing 100 μg/mL X-gal. This figure shows the difference in colony size on 100 µg/mL X-gal after lacZ counter-selection.

Fermentation analysis of B. smithii ET 138 wild-type and mutant strains in 1 L pH-controlled bioreactors after ±24 h. This table shows fermentation data in pH-controlled lab-scale reactors to supplement the data in tubes described in the main text.

Contributor Information

Elleke F Bosma, Email: elleke.bosma@wur.nl.

Antonius H P van de Weijer, Email: tom.vandeweijer@wur.nl.

Laurens van der Vlist, Email: laurensvdvlist@gmail.com.

Willem M de Vos, Email: willem.devos@wur.nl.

John van der Oost, Email: john.vanderoost@wur.nl.

Richard van Kranenburg, Email: r.van.kranenburg@corbion.com.

References

- 1.Werpy T, Petersen G, Aden A, Bozell J, Holladay J, White J et al (2004) Top value added chemicals from biomass. Volume 1-results of screening for potential candidates from sugars and synthesis gas. DTIC Document

- 2.Bozell JJ, Petersen GR. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates-the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited. Green Chem. 2010;12:539–554. doi: 10.1039/b922014c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhalla A, Bansal N, Kumar S, Bischoff KM, Sani RK. Improved lignocellulose conversion to biofuels with thermophilic bacteria and thermostable enzymes. Bioresour Technol. 2013;128:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.10.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma K, Maeda T, You H, Shirai Y. Open fermentative production of l-lactic acid with high optical purity by thermophilic Bacillus coagulans using excess sludge as nutrient. Bioresour Technol. 2014;151:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studholme DJ. Some (bacilli) like it hot: genomics of Geobacillus species. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;8:40–48. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ou MS, Mohammed N, Ingram LO, Shanmugam KT. Thermophilic Bacillus coagulans requires less cellulases for simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of cellulose to products than mesophilic microbial biocatalysts. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;155:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Zhou L, Kangming T, Kumar A, Singh S, Prior BA, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli: A sustainable industrial platform for bio-based chemical production. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1200–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong K-K, Nielsen J. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a key cell factory platform for future biorefineries. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2671–2690. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0945-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosma EF, van der Oost J, de Vos WM, van Kranenburg R. Sustainable production of bio-based chemicals by extremophiles. Curr Biotechnol. 2013;2:360–379. doi: 10.2174/18722083113076660028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor M, van Zyl L, Tuffin I, Leak D, Cowan D. Genetic tool development underpins recent advances in thermophilic whole-cell biocatalysts. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:438–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Lai Z, Lai C, Zhu M, Li S, Wang J, et al. Efficient production of l-lactic acid by an engineered Thermoanaerobacterium aotearoense with broad substrate specificity. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:124. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q, Chen T, Zhao X, Chamu J. Metabolic engineering of thermophilic Bacillus licheniformis for chiral pure D-2,3-butanediol production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:1610–1621. doi: 10.1002/bit.24427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, Ingram LO, Shanmugam KT. Evolution of d-lactate dehydrogenase activity from glycerol dehydrogenase and its utility for d-lactate production from lignocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18920–18925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111085108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs AT, van Hartskamp M, Kuipers OP, van Kranenburg R. Genetic tool development for a new host for biotechnology, the Thermotolerant Bacterium Bacillus coagulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4085–4088. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03060-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosma EF, van de Weijer AHP, Daas MJA, van der Oost J, de Vos WM, van Kranenburg R. Isolation and screening of thermophilic bacilli from compost for electrotransformation and fermentation: characterization of Bacillus smithii ET 138 as a new biocatalyst. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:1874–1883. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03640-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coorevits A, Dinsdale AE, Halket G, Lebbe L, de Vos P, Van Landschoot A, et al. Taxonomic revision of the genus Geobacillus: emendation of Geobacillus, G. stearothermophilus, G. jurassicus, G. toebii, G. thermodenitrificans and G. thermoglucosidans (nom. corrig., formerly ‘thermoglucosidasius’); transfer of Bacillus thermantarcticus to the genus as G. thermantarcticus; proposal of Caldibacillus debilis gen. nov., comb. nov.; transfer of G. tepidamans to Anoxybacillus as A. tepidamans and proposal of Anoxybacillus caldiproteolyticus sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:1470–1485. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cripps RE, Eley K, Leak DJ, Rudd B, Taylor M, Todd M, et al. Metabolic engineering of Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius for high yield ethanol production. Metab Eng. 2009;11:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Spanning RJ, Wansell CW, Reijnders WN, Harms N, Ras J, Oltmann LF, et al. A method for introduction of unmarked mutations in the genome of Paracoccus denitrificans: construction of strains with multiple mutations in the genes encoding periplasmic cytochromes c550, c551i, and c553i. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6962–6970. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6962-6970.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yudkin MD. Structure and function in a Bacillus subtilis sporulation-specific sigma factor: molecular nature of mutations in spoIIAC. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:475–481. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle NR, Reynolds TS, Evans R, Lynch M, Gill RT. Recombineering to homogeneity: extension of multiplex recombineering to large-scale genome editing. Biotechnol J. 2013;8:515–522. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Kranenburg R, Van Hartskamp M, Heintz E, Anthonius J, Van Mullekom E, Snelders J (2007) Genetic modification of homolactic thermophilic Bacilli. WO Patent WO/2007/085,4432007

- 22.Angelov A, Li H, Geissler A, Leis B, Liebl W. Toxicity of indoxyl derivative accumulation in bacteria and its use as a new counterselection principle. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lücking G, Stoeckel M, Atamer Z, Hinrichs J, Ehling-Schulz M. Characterization of aerobic spore-forming bacteria associated with industrial dairy processing environments and product spoilage. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;166:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoeckel M, Abduh S, Atamer Z, Hinrichs J. Inactivation of bacillus spores in batch vs continuous heating systems at sterilisation temperatures. Int J Dairy Technol. 2014;67(3):334–341. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming AB, Tangney M, Jørgensen PL, Diderichsen B, Priest FG. Extracellular enzyme synthesis in a sporulation-deficient strain of Bacillus licheniformis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3775–3780. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3775-3780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JJ, Greenhut WB, Shih JCH. Development of an asporogenic Bacillus licheniformis for the production of keratinase. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:761–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones SW, Tracy BP, Gaida SM, Papoutsakis ET. Inactivation of σF in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 blocks sporulation prior to asymmetric division and abolishes σE and σG protein expression but does not block solvent formation. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2429–2440. doi: 10.1128/JB.00088-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hols P, Ramos A, Hugenholtz J, Delcour J, De Vos WM, Santos H, et al. Acetate utilization in Lactococcus lactis deficient in lactate dehydrogenase: a rescue pathway for maintaining redox balance. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5521–5526. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5521-5526.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor: NY Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhee MS, Kim JW, Qian Y, Ingram LO, Shanmugam KT. Development of plasmid vector and electroporation condition for gene transfer in sporogenic lactic acid bacterium Bacillus coagulans. Plasmid. 2007;58:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaeffer AB, Fulton MD. A Simplified method of staining endospores. Science. 1933;77:194. doi: 10.1126/science.77.1990.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]