Abstract

Objective

Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a common cause of hearing loss and intellectual disability. We assessed CMV knowledge and the frequency of women's behaviors that may enable CMV transmission to inform strategies for communicating prevention messages to women.

Methods

We analyzed survey responses from 4184 participants (2181 women, 2003 men) in the 2010 HealthStyles survey, a national mail survey designed to be similar to the United States population.

Results

Only 7% of men and 13% of women had heard of congenital CMV. Women with children under age 19 (n=918) practiced the following risk behaviors at least once per week while their youngest child was still in diapers: kissing on the lips (69%), sharing utensils (42%), sharing cups (37%), and sharing food (62%). Women practiced protective, hand cleansing behaviors most of the time or always after: changing a dirty diaper (95%), changing a wet diaper (85%), or wiping the child's nose (65%), but less commonly after handling the child's toys (26%).

Conclusions

Few women are aware of CMV and most regularly practice behaviors that may place them at risk when interacting with young children. Women should be informed of practices that can reduce their risk of CMV infection during pregnancy.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, Congenital, Awareness, Behavior, Pregnancy

Introduction

Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a common cause of birth defects and developmental disabilities in the United States (Kenneson and Cannon, 2007), and is as prevalent as better-known conditions such as fetal alcohol syndrome or Down syndrome (Cannon, 2009). Approximately 30,000 U.S. children (∼1 in 150) are born with congenital CMV infection each year and of these approximately 5500 experience some form of disability (Dollard et al., 2007). Hearing loss is the most common CMV-related disability, but infected children may also experience vision loss, intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, and other forms of neuro developmental injury (Boppana et al., 1992; Istas et al., 1995; Sharon and Schleiss, 2007). Many women of reproductive age are CMV-seronegative and therefore at risk for primary infection during pregnancy (Bate et al., 2010), but even CMV-seropositive women can become reinfected and transmit newly acquired CMV strains to their fetuses (Wang et al., 2011). CMV-seropositive women may also transmit CMV to their fetuses as the result of viral reactivation.

There is evidence that maternal CMV infection may be prevented during pregnancy through education and behavioral change (Adler et al., 1996; Harvey and Dennis, 2008; Picone et al., 2009). However, prevention opportunities are missed because most women have not heard of CMV or how to prevent it (Bate and Cannon, 2011; Cannon and Davis, 2005; Jeon et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2008) and most obstetricians do not discuss CMV prevention with their patients (CDC, 2008) or are unaware of its precise transmission routes (Korver et al., 2009).

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that CMV transmission occurs through direct contact with infectious bodily fluids, such as urine, saliva, and semen (Cannon et al., 2010; Cannon et al., 2011; Hyde et al., 2010). Sexual contact can enable transmission (Robain et al., 1998; Staras et al., 2008b), but for women of reproductive age, exposure to urine and saliva of young children seems to be the biggest risk factor for transmission (Revello et al., 2008; Staras et al., 2008a). In fact, over the course of a year, mothers of children who are shedding CMV are ten times more likely to seroconvert than are women in various other comparison groups (Hyde et al., 2010). Because CMV is frequently found in children's saliva and urine (Cannon et al., 2011), most maternal infections probably occur as a result of these fluids getting into their eyes, nose, or mouth. The importance of these exposures was demonstrated in a large intervention trial that appeared to be responsible for lowering rates of CMV infection among pregnant women by focusing on behaviors such as frequent hand washing, not kissing young children on the mouth, and not sharing food or drink with young children (Vauloup-Fellous et al., 2009).

However, it is not known how frequently women practice behaviors that put them at risk for CMV infection when interacting with young children. Therefore, we surveyed women's knowledge of CMV, the frequency of behaviors that may enable CMV transmission, and patterns of health information-seeking in order to inform strategies for communicating CMV prevention messages to women.

Methods

HealthStyles survey

The data used in this research came from Porter Novelli's 2010 Styles database which is built from two consecutive surveys, ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles. ConsumerStyles is a market research survey and HealthStyles is a health topics survey that is sent to a subset of ConsumerStyles respondents. In spring 2010, ConsumerStyles surveys were mailed to a sample of 20,000 American adults who belong to a consumer mail panel of approximately 200,000 potential respondents managed by Synovate, Inc. Of these, 10,997 came from a main sample that was stratified on region, household income, population density, and household size to be similar to the U.S. population; 2996 came from a low income/minority supplement; and 6007 came from a households-with-children supplement. Of the 20,000 people sampled, 10,328 completed the ConsumerStyles survey, yielding a response rate of 51.6%. The HealthStyles survey was then sent to a random sample of 6255 respondents who completed the ConsumerStyles survey. A total of 4184 HealthStyles surveys were returned, for a response rate of 66.9%. Our analyses used data from these respondents, of whom 2181 were women and 2003 were men. The consumer mail panel is not representative of the U.S. population, although HealthStyles survey results are weighted to be similar to the demographic distribution of the United States.

On the HealthStyles survey we asked questions about awareness of a number of important childhood conditions, including congenital CMV. Separate sections of the survey had questions about health information-seeking behavior and behaviors that may be related to CMV transmission (see Appendix A). Face validity was established by having subject matter experts review the questions pertaining to CMV awareness and transmission.

Statistical analyses

We analyzed the data in 2011 using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). In all analyses responses were weighted to the U.S. Census Current Population Survey on the variables sex, age, race/ethnicity, income, and household size. Risk factors for CMV awareness or CMV transmission-related behaviors were assessed by using a test for linear trend for ordered variables and a test for homogeneity for unordered variables. Associations were considered significant if P<0.05.

Results

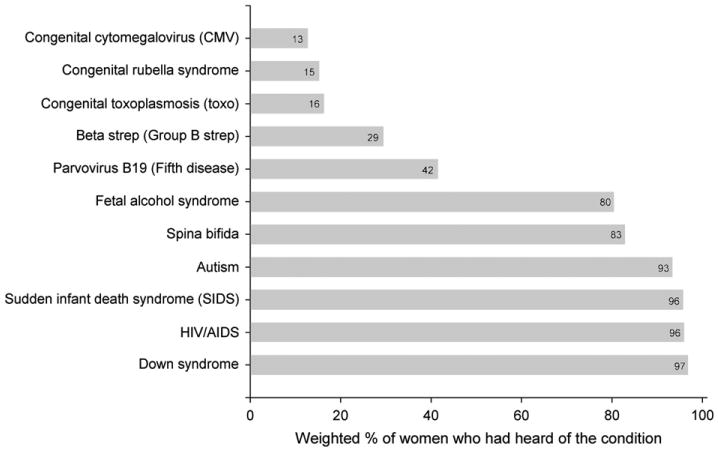

We found that 7% of men and 13% of women (p<0.001) reported having heard of congenital CMV. Among women, awareness of congenital CMV was lower than for any other childhood condition included in the survey (Fig. 1). Awareness among women varied significantly by age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, geographic region, and household income, although all variables had between-subgroup variation of less than 18 percentage points (Table 1). The strongest and most consistent association was found between higher congenital CMV awareness and higher educational attainment. Nevertheless, even among women with post-graduate college experience, congenital CMV awareness was only 21% (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of women (n=2181) who had heard of different childhood conditions, weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size. Based on the 2010 HealthStyles survey.

Table 1.

Estimated awareness of congenital CMV among U.S. women based on 2010 HealthStyles survey.

| Variable | No. who respondeda | No. who heard of congenital CMV | % who heard of congenital CMV (weighted)b | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 18–34 | 269 | 28 | 16 | |

| 35–44 | 407 | 53 | 13 | |

| 45–54 | 685 | 95 | 14 | |

| 55–64 | 397 | 43 | 11 | |

| 65+ | 423 | 31 | 7 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.02 | |||

| White | 1490 | 187 | 12 | |

| Black | 274 | 18 | 8 | |

| Hispanic | 277 | 25 | 20 | |

| Other | 140 | 20 | 12 | |

| Educational attainment | <0.001 | |||

| Did not graduate HS | 108 | 4 | 4 | |

| Graduated HS | 523 | 19 | 8 | |

| Attended college | 833 | 99 | 13 | |

| Graduated college | 438 | 69 | 15 | |

| Post graduate | 272 | 59 | 21 | |

| Geographic region | 0.003 | |||

| New England | 69 | 5 | 4 | |

| Middle Atlantic | 342 | 44 | 13 | |

| East North Central | 363 | 40 | 18 | |

| West North | 160 | 21 | 14 | |

| Central South Atlantic | 461 | 54 | 11 | |

| East South Central | 148 | 14 | 8 | |

| West South | 217 | 25 | 9 | |

| Central Mountain | 122 | 19 | 16 | |

| Pacific | 299 | 28 | 15 | |

| Household income | <0.001 | |||

| Under $15,000 | 355 | 22 | 7 | |

| $15,000–$24,900 | 203 | 12 | 12 | |

| $25,000–$39,900 | 285 | 18 | 7 | |

| $40,000–$59,900 | 354 | 42 | 13 | |

| $60,000+ | 984 | 156 | 17 |

Abbreviations: HS, high school.

A total of 2181 women responded.

Responses were weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size.

Test for linear trend for ordered variables and test for homogeneity for unordered variables.

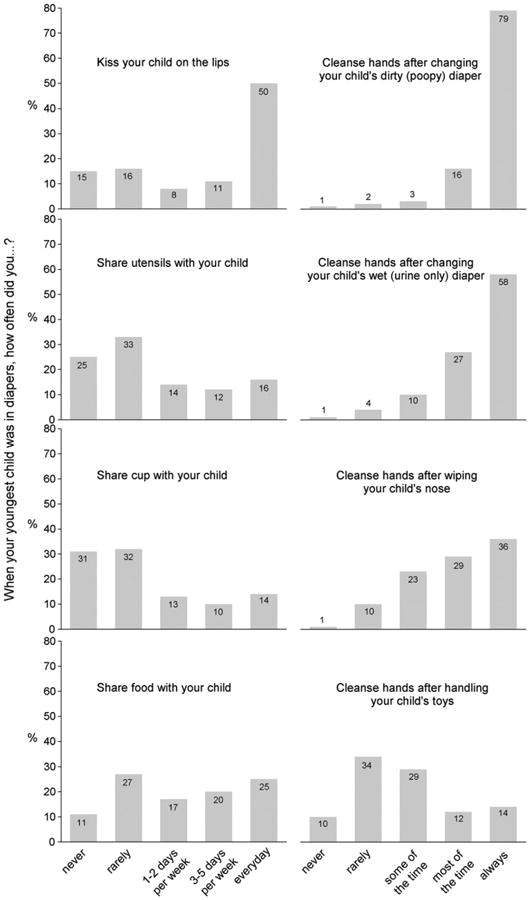

A substantial proportion of women with children under age 19 reported the following risk behaviors at least once per week while their youngest child was still in diapers: kissing on the lips (69%), sharing utensils (42%), sharing cups (37%), and sharing food (62%) (Fig. 2). These women practiced protective, hand cleansing behaviors most of the time or always in the following situations: after changing a dirty diaper (95%), after changing a wet diaper (85%), after wiping the child's nose (65%). Hand cleansing was less commonly practiced after handling the child's toys (26%) (Fig. 2). The prevalences of these behaviors varied significantly according to some demographic variables, although most (>80%) of the between-subgroup percentage differences were less than 20% (Tables 2 and 3). The most consistent association was with age, where older women were less likely to practice the risk behaviors (i.e., kissing, sharing) and more likely to practice the protective, hand cleansing behaviors (Tables 2 and 3). When stratifying by age, the relationships between women's behaviors and demographic variables did not reveal any new and consistent trends (data not shown). Frequencies among men were approximately the same as those among women for each of the hand cleansing behaviors and were approximately 10 percentage points lower for each of the kissing and sharing behaviors.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of women with children under 19 years of age (n=918) who reported practicing various behaviors when their youngest child was in diapers, weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size. Based on the 2010 HealthStyles survey.

Table 2.

Frequency of women with children <19 years (n=918) who reported various activities “at least once a week” based on 2010 HealthStyles survey.

| Demographic variables | “When your youngest child was in diapers, how often did you…?” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Kiss child on lips (%) | Share utensils with child (%) | Share cup with child (%) | Share food with child (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–34 | 76 | 51 | 49 | 69 |

| 35–44 | 65 | 40 | 32 | 61 |

| 45–54 | 65 | 29 | 27 | 52 |

| 55+ | 64 | 25 | 27 | 55 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 75 | 43 | 40 | 66 |

| Black or African American | 56 | 36 | 23 | 47 |

| Hispanic | 63 | 41 | 36 | 59 |

| Other | 60 | 44 | 39 | 57 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 65 | 43 | 39 | 58 |

| Attended college | 73 | 48 | 42 | 68 |

| Graduated college | 70 | 35 | 29 | 60 |

| Post graduate | 60 | 25 | 28 | 53 |

| Household income | ||||

| Under $15,000 | 63 | 37 | 47 | 59 |

| $15,000–$24,900 | 74 | 44 | 21 | 64 |

| $25,000–$39,900 | 70 | 41 | 42 | 58 |

| $40,000–$59,900 | 67 | 41 | 40 | 58 |

| $60,000+ | 70 | 42 | 36 | 65 |

Note: Responses were weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size. Shaded percentages are significant at P<0.05 either by a linear trend test (for the ordered variables age, education, and household income) or a test of homogeneity (for the unordered variable race/ethnicity).

Table 3.

Frequency of women with children <19 years (n=918) who reported cleansing hands “most of the time” or “always” after various activities based on 2010 HealthStyles survey.

| Demographic variables | “When your youngest child was in diapers, how often did you…?” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cleanse hands after changing dirty (poopy) diaper (%) | Cleanse hands after changing wet (urine only) diaper (%) | Cleanse hands after wiping child's nose (%) | Cleanse hands after handling child's toys (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–34 | 91 | 77 | 59 | 28 |

| 35–44 | 96 | 88 | 69 | 24 |

| 45–54 | 96 | 90 | 69 | 25 |

| 55+ | 95 | 95 | 72 | 31 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 96 | 87 | 64 | 22 |

| Black or African American | 85 | 70 | 69 | 44 |

| Hispanic | 96 | 91 | 66 | 26 |

| Other | 92 | 74 | 60 | 30 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 89 | 84 | 69 | 32 |

| Attended college | 95 | 83 | 64 | 29 |

| Graduated college | 97 | 86 | 64 | 20 |

| Post graduate | 95 | 89 | 65 | 17 |

| Household income | ||||

| Under $15,000 | 91 | 86 | 69 | 50 |

| $15,000–$24,900 | 99 | 77 | 68 | 25 |

| $25,000–$39,900 | 87 | 82 | 62 | 24 |

| $40,000–$59,900 | 98 | 91 | 75 | 38 |

| $60,000+ | 94 | 84 | 61 | 18 |

Note: Responses were weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size. Shaded percentages are significant at P<0.05 either by a linear trend test (for the ordered variables age, education, and household income) or a test of homogeneity (for the unordered variable race/ethnicity).

Just over half of women reported looking for health information on the web (Table 4). Most of them used search engines or health information portals like WebMD or Dr. Koop as sources of health information rather than the websites of government or non-profit organizations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Health information seeking on the Internet among U.S. women (n=2181) based on the 2010 HealthStyles survey.

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you look for health info on the web? | 55 | 45 |

| What online sources for health information do you use? | ||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | 28 | 72 |

| Other government agencies (like National Institutes of Health–NIH | 22 | 78 |

| Non-profit organizations (like American Heart Association) | 30 | 70 |

| Health information portals (like WebMD and Dr. Koop) | 64 | 36 |

| Search engines (like Google, Yahoo, and MSN) | 75 | 25 |

| Media sites (like CNN and New York Times) | 10 | 90 |

Note: Responses were weighted to be similar to the U.S. population with respect to benchmarks on age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and household size.

Discussion

We found that awareness of CMV among women was very low, lower than for any other condition asked about on the survey (Fig. 1), even though disabilities caused by congenital CMV are more prevalent than most of the other conditions (Cannon, 2009). Some subgroups had slightly higher awareness than others, but in all subgroups the vast majority had never heard of congenital CMV. Compared to awareness from the HealthStyles survey administered five years earlier that used a similar population and the same survey methodology (Ross et al., 2008), current CMV awareness was not any higher. Awareness of congenital rubella syndrome and congenital toxoplasmosis was slightly greater than awareness of congenital CMV, even though the former has nearly been eliminated in the United States and the latter occurs approximately 100 times less frequently than congenital CMV infection. These findings indicate the need for a major awareness effort that educates the public about congenital CMV and methods for preventing maternal infection during pregnancy.

This is the first study we are aware of that surveyed the prevalence of behaviors related to CMV transmission. We found that behaviors that may place women at risk for CMV infection when interacting with young children are common (Fig. 2). Risk behaviors that involve direct transmission routes (i.e., kissing, sharing) are especially common, in particular kissing young children on the lips. Protective behaviors (i.e. hand cleansing) that involve the indirect transmission routes (i.e., hands, surfaces) are practiced frequently, but a minority of women may still be at risk because they do not always cleanse hands after possible exposures to urine or saliva. Because the frequencies of some behaviors differ significantly by demographic variables (Tables 2 and 3), prevention messages that target particular subgroups may need to be sensitive to these differences (e.g., prevalence of oral transmission risk behaviors in Whites and Blacks). Nevertheless, behavioral differences do not seem substantial enough to warrant emphasizing particular behaviors with different demographic subgroups.

Determining the optimal content of prevention messages remains a challenge. The biology and epidemiology of CMV infection strongly suggest that the greatest transmission risk for mothers is getting urine or saliva from young children in their eyes, nose, or mouth (Cannon et al., 2011; Hyde et al., 2010; Revello et al., 2008). However, there are multiple ways this may occur and it is difficult to tease out the relative importance of each potential route of exposure. In general, we found that women more frequently practice behaviors that enable direct transmission and less frequently practice behaviors that enable indirect transmission. In addition, CMV is less likely to remain infectious during an indirect transmission behavior (e.g., child's mouth-to-toy-to-mother's hand-to-mother's eye) than a direct behavior (e.g., kissing) since CMV becomes non-infectious after drying out (Stowell et al., 2012) and demonstrates short survival time on hands (Faix, 1987). Thus, because of their high frequency of occurrence and higher likelihood of preserving viral infectiousness, the direct transmission routes are of particular concern.

In our survey we chose to ask questions about some of the behaviors that frequently have been included in experts' suggested guidelines or in prevention trials (Adler et al., 1996; Cannon and Davis, 2005; Demmler-Harrison, 2009; Picone et al., 2009). In future studies it may be useful to assess the frequency of additional behaviors. For instance, a mother cleaning a child's pacifier in her mouth and sharing a toothbrush with a child are direct transmission behaviors that have been little mentioned in the literature. However, if they are only practiced rarely they may not need to be added to prevention guidelines. Sleeping in the same bed and sharing towels have been mentioned in the literature but are indirect transmission behaviors that are probably of less concern (Adler et al., 2004; Vauloup-Fellous et al., 2009). Nevertheless, understanding their frequency would help inform future prevention guidelines. Because some of the behaviors we studied (e.g., kissing, sharing food) represent cultural norms or usual mother-child intimacy among some subgroups in the United States, it will be important to understand how to frame the behavioral guidelines in a way that increases the likelihood that women will accept them and incorporate them into their daily routines. Previous research suggests that women are receptive to such guidelines even though they may represent a departure from cultural norms (Adler, 2011; Ross et al., 2008; Vauloup-Fellous et al., 2009). Because CMV reactivation may be responsible for some congenital CMV infections, not all congenital infections may be preventable by avoiding CMV exposures.

Determining the optimal communication channels for reaching at-risk women with CMV prevention messages is also a challenge. Just over half of respondents said that they look for health information on the Internet, and most of them use a search engine to find this information. These results are similar to other data that indicate approximately 59% of adults look on-line for health information (Atkinson et al., 2009; Fox, 2011), making the Internet an important potential communication channel. However, rates of health information seeking on the Internet tend to be higher among those with more education and income and thus a large segment of the population may not receive messages through this channel. In addition, while social media use (e.g., Twitter, Facebook) is also prevalent and trending upwards (Rainie et al., 2011; Smith, 2011), very few adults who go on-line to seek health information have used social networking sites to follow friends' experiences with health issues or to post information about their own health (Fox, 2011). Despite the availability of information on the Internet, health professionals, trusted friends, and family members are still the preferred sources of health information (Fox and Jones, 2009). Important communications channels might include the offices of obstetricians, nurse midwives, and other health professionals who provide care for women and children; day care centers and pre-K schools; and pregnancy and childbirth classes.

Our study had several limitations. First, although HealthStyles respondents are similar to the U.S. population according to certain demographic characteristics, they are not necessarily generalizable to the U.S. population. Nevertheless, their agreeing to participate in the consumer panel does not appear to lead to biased responses for a variety of health-related survey items (Pollard, 2007). Second, survey behaviors were self-reported, making it more likely that socially desirable responses were over reported. For example, hand washing may not occur as frequently as reported. Observational studies of behaviors in the home or day care settings may be able to obtain less-biased estimates. Third, recall bias could be substantial since events occurred upto 15 years previously for some women. This could partially explain why older women were less likely to report risk behaviors and more likely to report hand cleansing. Surveys of more recent behavior may help remedy this potential bias. Fourth, differences between responders and non-responders could have resulted in biased results. Al-though we had no information on non-responders, we would speculate that responders may be more health-conscious than non-responders, and therefore women may actually practice more of the risk behaviors and fewer of the protective behaviors than what we reported. Last, the survey did not ask if women were currently pregnant. It is possible that the behaviors we studied have different frequencies women. Because pregnant women often modify behaviors that pose risks to their fetuses, such as smoking or drinking, it seems likely that many will also modify behaviors related to CMV transmission if they are made aware of them.

In conclusion, CMV awareness among women is very low and needs to be raised using current knowledge and best practices. Further research should seek to better understand the prevalence of risk and protective behaviors among women, especially those at highest risk for infection. Finally, prevention concepts, messages, and materials should be evaluated for their ability to improve knowledge, induce behavioral changes, and reduce CMV infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brook Nash for assistance with the development of the survey questions.

Abbreviations

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

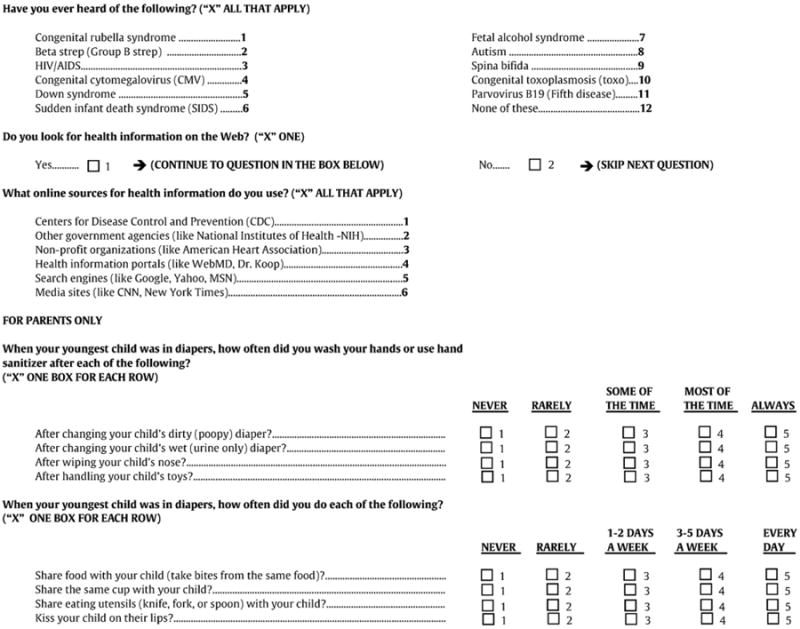

Appendix A. Survey questions

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of interest: R.F. Pass: Consultant to Merck and Astellas, partial interest in a patent relevant to CMV vaccine development; All other authors: no financial disclosures related to this paper.

References

- Adler SP. Screening for cytomegalovirus during pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/942937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler SP, Finney JW, Manganello AM, Best AM. Prevention of child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus by changing behaviors: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:240–246. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler SP, Finney JW, Manganello AM, Best AM. Prevention of child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus among pregnant women. J Pediatr. 2004;145:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate SL, Cannon MJ. A social marketing approach to building a behavioral intervention for congenital cytomegalovirus. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12:349–360. doi: 10.1177/1524839909336329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate SL, Dollard SC, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States: the national health and nutrition examination surveys, 1988–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1439–1447. doi: 10.1086/652438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Alford CA. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:93–99. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) epidemiology and awareness. J Clin Virol. 2009;46S:S6–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MJ, Davis KF. Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:240–255. doi: 10.1002/rmv.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Knowledge and practices of obstetricians and gynecologists regarding cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy— United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmler-Harrison GJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus: public health action towards awareness, prevention, and treatment. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:355–363. doi: 10.1002/rmv.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faix RG. Comparative efficacy of handwashing agents against cytomegalovirus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1987;8:158–162. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700065826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. The social life of health information[Online] 2011 Available: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx2011.

- Fox S, Jones S. The social life of health information[Online] 2009 Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/8-The-Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx2009.

- Harvey J, Dennis CL. Hygiene interventions for prevention of cytomegalovirus infection among childbearing women: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63:440–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde TB, Schmid DS, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroconversion rates and risk factors: implications for congenital CMV. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:311–326. doi: 10.1002/rmv.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istas AS, Demmler GJ, Dobbins JG, Stewart JA. Surveillance for congenital cytomegalovirus disease: a report from the National Congenital Cytomegalovirus Disease Registry. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:665–670. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J, Victor M, Adler S, et al. Knowledge and awareness of congenital cytomegalovirus among women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2006:1–7. doi: 10.1155/IDOG/2006/80383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253–276. doi: 10.1002/rmv.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korver AMH, De Vries JJC, De Jong JW, Dekker FW, Vossen A, Oudesluys-Murphy AM. Awareness of congenital cytomegalovirus among doctors in the Netherlands. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picone O, Vauloup-Fellous C, Cordier AG, et al. A 2-year study on cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy in a French hospital. BJOG - Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116:818–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard WE. Proceedings of the Section on Health Policy Statistics, American Statistical Association. 2007. Evaluation of consumer panel survey data for public health communication planning: an analysis of annual survey data from 1995–2006; pp. 1528–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Rainie L, Purcell K, Smith A. The social side of the internet[Online] 2011 Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2011/Social-Side-of-the-Internet.aspx2011.

- Revello MG, Campanini G, Piralla A, et al. Molecular epidemiology of primary human cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women and their families. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1415–1425. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robain M, Carre N, Dussaix E, Salmon-Ceron D, Meyer L. Incidence and sexual risk factors of cytomegalovirus seroconversion in HIV-infected subjects. The SEROCO Study Group. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:476–480. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DS, Victor M, Sumartojo E, Cannon MJ. Women's knowledge of congenital cytomegalovirus: results from the 2005 HealthStyles survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:849–858. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon B, Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: an unrecognized epidemic. Infect Med. 2007;24:402–415. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Twitter update[Online] 2011 Available: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Twitter-Update-2011.aspx2011.

- Staras SA, Flanders WD, Dollard SC, Pass RF, Mcgowan JE, Jr, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and childhood sources of infection: a population-based study among pre-adolescents in the United States. J Clin Virol. 2008a;43:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staras SA, Flanders WD, Dollard SC, Pass RF, Mcgowan JE, Jr, Cannon MJ. Influence of sexual activity on cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States, 1988–1994. Sex Transm Dis. 2008b;35:472–479. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644b70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell JD, Forlin-Passoni D, Din E, et al. Cytomegalovirus survival on common environmental surfaces: opportunities for viral transmission. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:211–214. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Cordier AG, et al. Does hygiene counseling have an impact on the rate of CMV primary infection during pregnancy? Results of a 3-year prospective study in a French hospital. J Clin Virol. 2009;46S:S49–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CB, Zhang XY, Bialek S, Cannon MJ. Attribution of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary versus non-primary maternal infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:E11–E13. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]