Abstract

People who live with concealable stigmatized identities face complex decisions regarding disclosure. In the current work, we examine how people's motivations for disclosing a concealable stigmatized identity for the first time affect the quality of their first disclosure experiences and how these experiences, in turn, affect current well-being. Specifically, we found that people who disclosed for ecosystem, or other-focused, reasons report more positive first disclosure experiences which, in turn, were related to higher current self-esteem. Analyses suggest that one reason why this first disclosure experience is related to current well-being is because positive first disclosure experiences may serve to lessen chronic fear of disclosure. Overall, these results highlight the importance of motivational antecedents for disclosure in impacting well-being and suggest that positive first disclosure experiences may have psychological benefits over time because they increase level of trust in others.

Keywords: concealable stigmatized identity, disclosure, motivation, self-esteem

Although all stigmatized individuals experience potential challenges due to their socially devalued status (for reviews, see Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Major & O'Brien, 2005), people who possess a concealable stigmatized identities face a number of unique psychosocial challenges, including those associated with disclosure (Pachankis, 2007; Quinn, 2006). Once individuals make the difficult decision to tell another person about the identity, disclosure can potentially affect a wide range of psychological (e.g., distress), health (e.g., illness progression), and behavioral outcomes (e.g., performance; for a review, see Chaudoir & Fisher, in press).

In the current research, we examine how first disclosure experiences are related to current psychological well-being in a sample of people living with a variety of concealable stigmatized identities. In the current work, we examine how people's motivations for disclosing for the first time affect the quality of their first disclosure experiences and how these experiences, in turn, affect psychological well-being. Additionally, we examine one potential mediating mechanism—fear of disclosure—that may explain how people's first disclosure event can continue to impact psychological well-being long after the event.

First Disclosure Experiences

Results from a wide body of work examining the consequences of disclosure suggest that telling another person about a concealable stigmatized identity has the potential to yield psychological benefits. The active concealment of a concealable stigmatized identity can be psychologically stressful (e.g., Smart & Wegner, 1999) or make people feel guilty about keeping the information from others (Derlega, Metts, Petronio, & Margulis, 1993), and disclosure can help to alleviate these effects (for reviews, see Pennebaker, 1997; Smyth, 1998). However, accumulating experimental evidence suggests that interpersonal disclosure may only yield psychological benefits when disclosures are met with positive, supportive responses from disclosure confidants (Lepore, Ragan, & Jones, 2000; Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006).

Although all disclosure experiences have the potential to affect psychological well-being, first disclosure experiences may have a particularly robust effect on subsequent well-being and disclosure behavior. For example, disclosure of history of abortion or sexual assault may provide no psychological benefits and may even be detrimental when met with socially rejecting or blaming responses from disclosure confidants (Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Ullman, 1996; Major, Cozzarelli, Sciacchitano, Cooper, Testa, & Mueller, 1990). Further, these negative confidant responses can also serve to silence people from disclosing again in the future (Ahrens, 2006). Given the importance of first disclosure events for future well-being, what antecedent factors are related to positive first disclosures? The present work examines the impact of disclosure motivations on the outcomes of first disclosure events.

Disclosure Motivations

Disclosure has long been theorized to be a goal-oriented behavior wherein people have specific motivations and goals for disclosing their concealable stigmatized identity to others (Derlega & Grzelak, 1979; Omarzu, 2000). That is, people have an idea of what they would like to accomplish by disclosing, such as obtaining valuable social support or professional treatment or strengthening their relationships with close others. Although people's motivations and goals for disclosure are certainly shaped by the nature of their specific concealable stigmatized identity (e.g., Derlega, Winstead, Greene, Serovich, & Elwood, 2004), there is a great degree of overlap in the reasons why people choose to disclose (Derlega & Grzelak, 1979). Disclosure motivations, therefore, provide a useful framework to consider the common disclosure processes that occur across a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities (Chaudoir & Fisher, in press). Although many studies have examined the types of motivations and goals that people have for disclosing (e.g., Derlega et al., 2004; Greene, Frey, & Derlega, 2002), this research has rarely considered how disclosure motivations impact the actual outcomes of disclosure.

Research from other domains of social psychology, however, suggests that motivations can shape the outcomes of behavior in important ways (e.g., Dweck, 1986; Higgins, 1998). Recent theorizing by Crocker and colleagues suggests that two motivational systems shape behavior—the egosystem and the ecosystem (Crocker, 2008; Crocker, Garcia, & Nuer, 2008; also termed self-image and compassionate goals, respectively, Crocker & Canevello, 2008). According to their theorizing, egosystem motivations are people's default motivations and reflect a focus on satisfying the needs and desires of the self, perpetuating positive self-images, and obtaining desired outcomes while avoiding harmful ones. Egosystem motivations for disclosure emphasize how disclosing might yield desirable outcomes for the self (e.g., catharsis) or avoid undesirable outcomes for the self (e.g., social rejection). In contrast, ecosystem motivations consider the well-being of others and place oneself as part of a larger structure of human interconnectedness. Ecosystem motivations for disclosure emphasize how disclosure might affect both the self and their disclosure confidant and could yield positive outcomes for both the self and for others (e.g., strengthen personal relationships, educate others) and avoid undesirable outcomes for the self and for others (e.g., other people bearing their stigmatized identities alone).

Importantly, recent evidence suggests that ego- vs. ecosystem disclosure motivations can impact the outcomes of disclosure. Researchers assessed ego- and ecosystem motivations for disclosure, disclosure behavior, and psychological well-being each day for 2 weeks among people who were concealing depression or sexual minority status (Garcia & Crocker, 2008). Results demonstrate that people who had ecosystem motivations disclosed more often and reported greater psychological benefits when they did disclose. That is, both baseline and daily ecosystem motivations predicted higher rates of disclosure whereas egosystem motivations were related to lower rates of disclosure for both depressed and sexual minority participants.

In the present study, we utilize the ego- vs. ecosystem motivational framework provided by Crocker and colleagues (Crocker et al., 2008; Crocker, 2008) to examine how motivations for disclosure affect the outcomes of first disclosure experiences. In doing so, our data extend the initial findings provided by Garcia and Crocker (2008) in three important ways. First, by examining the impact of motivations on the outcomes of first disclosure experiences, we can examine whether the impact of ecosystem motivations on well-being operates similarly for the very first disclosure event as it has been demonstrated to work for disclosures that occur when people are already fairly open about their identity. Second, whereas the Garcia and Crocker (2008) study examines the impact of motivations on well-being without attention to how the disclosure events themselves unfolded, our data allow us to examine whether motivations are related to the perceived outcome of the disclosure event and current well-being. And third, by examining a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities, our data allow us to extend the generalizability of the ego/ecosystem framework findings beyond depression and sexual orientation.

We predicted that participants who reported ecosystem reasons for disclosing would experience greater first disclosure positivity. However, how does the first disclosure event—an event that could have occurred many years in the past—impact people's long-term psychological well-being? That is, how does first disclosure positivity continue to impact people's feelings and thoughts after that specific disclosure situation has ended? Research examining this question has been less plentiful.

Fear of Disclosure

We propose that one reason why first disclosure events have the power to impact people's long-term psychological well-being is because they affect people's beliefs about disclosure. That is, when people have positive and supportive first disclosure events, their beliefs about disclosure may become more positive—they may see disclosure as a more favorable and beneficial behavior. One way to assess these beliefs is through fear of disclosure—people's chronic fear of and hesitancy towards disclosing their personal secrets to others. Given that disclosure is something that people with concealable stigmatized identities will have to potentially deal with for the rest of their lives, fear of disclosure could represent a chronic worry that could influence overall psychological well-being, a finding that has been supported in the context of disclosure of sexual orientation in the workplace (Ragins, Singh, & Cornwell, 2007). Presumably, degree of fear of disclosure is largely informed by prior disclosure experiences. The current work tests this assumption and examines how a distinct disclosure event—the first disclosure experience—may impact fear of disclosure and, ultimately, general well-being. Further, by examining these effects among a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities, we attempt to generalize Ragins and colleagues' (2007) results to new identities.

Overview of the Current Research

In the current work, we examine how ecosystem disclosure motivations, first disclosure positivity, and fear of disclosure influence psychological well-being in a sample of participants who possess a concealable stigmatized identity. Whereas previous disclosure research has typically examined these issues within specific populations (e.g., mental illness, HIV/AIDS, or sexual assault; Ahrens, 2006; Corrigan, 2005; Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2007) and has rarely integrated the implications of these study findings across populations, the current work offers a novel approach by identifying potential commonalities of disclosure dynamics across a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities. Although there are important differences between specific concealable stigmatized identities in domains such as origin (e.g., a traumatic event vs. a diagnosis) or disruptiveness to an individual's life, we suggest that the psychological processes that are involved in disclosure—making a decision to disclose, actually telling another person about the identity, and the subsequent consequences of doing so—are unifying dimensions that allow researchers to understand the disclosure experiences of people who bear a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities.

In the current research, we hypothesized that people who reported an ecosystem motivation for disclosing would experience greater first disclosure positivity than those who did not posses such motivations. Further, we hypothesized that first disclosure positivity would be a predictor of current psychological well-being (as measured by self-esteem), although we expected that this relationship would be mediated by fear of disclosure.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students were recruited to participate in a study about experiences with concealed identities if they indicated during a pre-screening session that they possessed an identity that they normally kept concealed and which others would react to either negatively or with surprise. We deliberately used these broad criteria in order to obtain a variety of different concealed identities. A total of 282 participants indicated a codable stigmatized identity; of these, 47 were excluded because they did not provide a description of their first disclosure situation that could be coded, leaving a total of 235 participants in the current analyses. Participants completed the survey as partial fulfillment of a course requirement. Participants were predominantly female (76.6%), Caucasian (83.0%), and the mean age was 18.6 years (SD = 1.1).

Procedure

The first page of the survey gave an explanation of a concealed identity, followed by examples of positive, negative, and neutral identities. We reminded them that they were selected because they had indicated in the prescreening that they had something about themselves that they regularly kept hidden. The participants were then asked to describe their concealed identity in their own words and were told that this identity would be referred to as their “concealed identity” in the survey. Participants then were asked to complete an open-ended essay in which they were asked to describe the “situation in which you first revealed your concealed identity (i.e,. who you told, why you chose to reveal the identity, what his/her reaction was, how you felt during and after this situation, etc.).”

Two presentation orders of these materials were created such that half of the participants completed the questions about the concealed identity, their first disclosure event and their evaluations of it followed by trait level measures including fear of disclosure and self-esteem, and the other half completed the measures in the reverse order. Order of presentation did not affect the results. All participants were assured of their anonymity, and each participant completed the survey alone in a small cubicle. These measures were part of a larger survey on concealable stigmatized identities (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009).

Measures

Nature of the concealed identity

Two raters coded the open-ended responses describing the concealed identity into one of 10 categories, such as mental illness (e.g., depression, obsessive compulsive disorder), weight/appearance concerns (e.g., eating disorder), and medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, epilepsy). Please see Table 1 for a full list of identities. Inter-rater reliability was high (κ = .93) and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Participants indicated that they had possessed their identity from less than a year (4.7%) to their entire life (5.1%), with a mean of approximately 6 years (SD =3.89).

Table 1. Outcome Means and Standard Deviations as a Function of Type of Concealable Stigmatized Identity (N = 235).

| Type of concealable stigmatized identity | N | Ecosystem motivations (%) | First disclosure positivity | Fear of disclosure | Self-esteem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental illness | 74 | 23 | 5.70 (1.14) | 4.01 (1.20) | 4.38 (1.25) |

| Weight/appearance issues | 26 | 31 | 5.14 (1.66) | 4.15 (1.28) | 4.25 (1.27) |

| Family medical/psychological issue | 25 | 16 | 5.95 (0.83) | 3.38 (1.03) | 5.19 (0.82) |

| Medical condition | 22 | 32 | 6.14 (0.89) | 3.01 (1.37) | 5.30 (.99) |

| Sex-related | 18 | 39 | 4.74 (1.75) | 3.44 (1.22) | 4.91 (1.21) |

| Abusive/dysfunctional family | 18 | 39 | 5.66 (1.14) | 3.71 (1.41) | 4.98 (1.24) |

| Family addiction | 18 | 39 | 6.13 (1.17) | 3.06 (1.00) | 5.06 (1.22) |

| Sexual assault | 13 | 8 | 5.69 (0.82) | 3.18 (1.32) | 5.12 (1.14) |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 11 | 36 | 6.48 (0.46) | 3.44 (1.38) | 5.45 (1.16) |

| Sexual orientation | 10 | 30 | 5.90 (1.05) | 3.76 (1.28) | 4.67 (1.53) |

Note. All measures are assessed on a 7-point Likert scale.

Ecosystem motivation for disclosure

Two raters coded the open-ended essays describing participants' first disclosure event. These raters first developed a coding scheme by noting recurring reasons for disclosure that were written in these essays. The coding scheme yielded 9 separate categories: (1) participant felt especially close to the confidant, (2) confidant disclosed a concealable stigmatized identity first, (3) participant knew confidant had a concealable stigmatized identity, (4) catharsis (i.e., wanted to get information off one's chest), (5) participant was confronted by the situation and was forced to disclose, (6) participant needed to tell to get help or treatment, (7) confidant was told about the concealable stigmatized identity by a 3rd party, (8) no reason given, and (9) other. Each essay was coded into one of these 9 categories. Only 4 (2%) of participants reported multiple distinct motivations for disclosure. When multiple motives were described, we coded the essay based on the motivation that was written first in the description. Inter-rater reliability was high (κ = .88) and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Given that egosystem motivations—those concerned with the self's well-being—are assumed to be the default motivations for disclosure, we were most interested in how those participants who reported ecosystem, or other-focused, motivations for disclosure would differ from those who did not. Given that ecosystem motivations reflect a relational concern regarding how disclosure may impact both the self and the disclosure confidant (Crocker et al., 2008; Crocker, 2008; Garcia & Crocker, 2008), we determined that 3 of our 9 categories would qualify as ecosystem motivations for disclosure: (1) participant felt especially close to the confidant (e.g., “I revealed it because I trusted the person enough and I felt close enough to them to reveal my identity” and “I chose to reveal it to her because I tell her everything and it was something I wanted to share with her”), (2) confidant disclosed a concealable stigmatized identity first (e.g., “I revealed it to a friend who had confided her similar concealed identity to me” and “the only reason why I told her was because she told me about a similar experience”, and (3) participant knew confidant had a concealable stigmatized identity (e.g., “I talked to my friend about it because I knew that he had some of the same issues” and “I told my best friend because a similar thing happened to her”). Each of these disclosure motivations can be considered to be ecosystem motivations because they reflect a concern with the relationship that the participant has with the disclosure confidant. Ultimately then, we dichotomized our 9 categories into a new variable in order to indicate the presence or absence of ecosystem motivations.

First disclosure positivity

After describing their first disclosure experience in an open-ended essay format, participants were asked to answer 3 items assessing the overall positivity of the event. Participants answered the following questions on 7-point Likert scales: (1) “How accepting of you was the person after learning of your concealed identity?” (1 = not at all accepting; 7 = very accepting), (2) “How supportive of you was the person after learning of your concealed identity?” (1 = not at all supportive; 7 = very supportive), and (3) “How would you describe the overall experience of revealing your concealed identity for the first time?” (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive). These 3 items were highly intercorrelated, all rs >.54, and an exploratory factor analysis confirmed that these items had a 1-factor structure. Therefore, we combined these items to create an overall measure of first disclosure positivity (α =.82).

Fear of disclosure

Eight items comprising the fear of disclosure subscale of the Interpersonal Trust Questionnaire (Forbes & Roger, 1999) were used to assess the extent to which participants had concerns about disclosing private information to others. In the original validation study, fear of disclosure was related to greater levels of emotional inhibition and lower perceptions of social support, suggesting that fear of disclosure is related to tendencies to hide or suppress emotions and feel distant from others. Items such as “I am afraid that people will laugh at me if I tell them my problems” and “Sometimes I am unable to confide even in someone who is close to me” were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). These items were combined such that higher values indicate a greater degree of fear of disclosure (α = .83).

Self-esteem

Trait self-esteem was measured with the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). This 10-item scale assesses feelings of self-worth with items such as “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others” and “I feel I do not have much to be proud of” (reverse-coded) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree). Items are averaged, with larger numbers indicating higher self-esteem (α = .90).

Results

Descriptive

Participants reported a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities. Mental illness was the most commonly reported identity (31.5%), followed by weight and appearance issues (11.1%) and family medical/psychological issue (10.6%, see Table 1 for a full list of identities). Data coded from the essay also indicate that 27.7% of our sample reported an ecosystem disclosure motivation for their first disclosure event. Although we were not able to conduct statistical comparisons between the types of concealable stigmatized identities because of the low number of participants in several of the categories, we can examine the trends in the outcome variables. Table 1 indicates that participants concealing a history of sexual assault were the least likely to report an ecosystem motivation for their first disclosure experience whereas participants concealing a sex related stigma, abusive/dysfunctional family, or family addiction were most likely to report an ecosystem motivation for their first disclosure experience.

Overall, the majority of participants indicated that their first disclosure event was a positive experience. The average rating of the first disclosure event was 5.71 (SD = 1.23), and only 11.5% of participants had average ratings of their first disclosure event that were at the midpoint of the scale or below. Participants who disclosed a history of childhood sexual abuse reported the highest degree of first disclosure positivity, whereas participants who disclosed a sex related stigmatized identity reported the lowest degree of first disclosure positivity.

Overall, participants reported a moderate degree of fear of disclosure and self-esteem, (M = 3.64, SD = 1.27; M = 4.78, SD = 1.23; respectively). Participants with a hidden medical condition reported the lowest degree of fear of disclosure whereas participants with weight/appearance issues reported the highest degree of fear of disclosure. Participants with weight/appearance issues reported the lowest levels of self-esteem whereas participants with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported the highest levels of self-esteem.

Effects of disclosure variables on psychological well-being

In order to test our hypothesis that participants who held an ecosystem motivation for disclosure would experience a more positive first disclosure experience than participants who did not, we compared these two groups of participants in an independent samples t-test. Consistent with hypotheses, participants who reported disclosing because they held ecosystem motivations for doing so reported that the disclosure event was more positive (M = 6.03, SD = 1.10) than did those participants who did not disclose for ecosystem motivations (M = 5.58, SD = 1.26, t(233) = 2.52, p < .05).

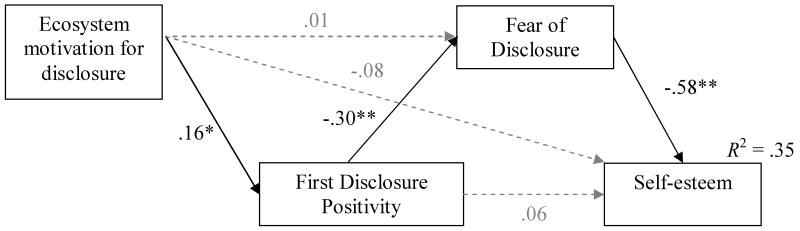

In order to examine the hypothesized relationships among all of our variables, we utilized structural equation modeling (See Figure 1). We assessed model fit with four indices: Chi-square, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1998), comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987). A non-significant chi-square value, a RMSEA value of .06 or lower, and a CFI value greater than .95 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We also report the AIC, which is a goodness-of-fit measure that is adjusted to penalize for model complexity and allows us to compare alternative models that may not be hierarchically nested. Thus, when comparing alternative models, the one with the lower AIC is preferred (Hu & Bentler, 1995).

Figure 1.

Full Structural Equation Model.

We hypothesized that ecosystem motivations would be related to greater first disclosure positivity and that the relationship between first disclosure positivity and self-esteem would be mediated by fear of disclosure. We first examined the full, saturated model and found that the relationships between ecosystem motivations and fear of disclosure, ecosystem motivations and self-esteem, and first disclosure positivity and self-esteem were nonsignificant. After trimming these nonsignificant paths, our final model fit the data well, χ2 (2) = 2.50, n.s., Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .99, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .03, AIC = 18.50, and it accounted for 35% of the variance in self-esteem. Results of our analyses demonstrate support for a model indicating that participants who had an ecosystem motivation for disclosure were more likely to experience a positive first disclosure event and that first disclosure positivity was related to decreased fear of disclosure which, in turn, led to higher levels of self-esteem. Examination of the indirect effects of this model using bootstrapped resampling (for a review, see MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007) indicate that the standardized indirect, or mediated, effect of first disclosure positivity on self-esteem was significant (β = .17, SE = .04, CI = 0.12 - 0.24, p < .01). This relationship remained significant even after controlling for the effect of gender and time since onset of the concealable stigmatized identity. Thus, our model suggests that the salutary effects of a positive first disclosure experience for psychological well-being are due to the mediating role of fear of disclosure.

An important caveat in the interpretation of our results is that the correlational nature of our data does not allow us to make firm conclusions about causality among our variables. We can, however, examine the validity of several alternative models in order to provide additional evidence to clarify the relationships among these constructs. One possibility is that the order of causation among our variables is reversed such that current self-esteem or fear of disclosure could color the way in which participants recalled their first disclosure event. We conducted tests of two additional alternative models in which the causal order of our variables is reversed and current self-esteem or fear of disclosure impacts the other variables. In the first, we treated self-esteem as the only exogenous variable predicting 3 endogenous variables—fear of disclosure, ecosystem motivations, and disclosure positivity—and in the second, we treated fear of disclosure as the only exogenous variable predicting 3 endogenous variables—self-esteem, ecosystem motivations, and disclosure positivity. In each of these 2 models, the 3 endogenous variables were correlated with each other in the saturated model. In the former model, self-esteem predicted lowered fear of disclosure and greater disclosure positivity, but was not related to ecosystem motivations. In the latter model, fear of disclosure was related to lowered self-esteem and disclosure positivity, but was not related to ecosystem motivations. Thus, it is unlikely that current levels of self-esteem or fear of disclosure are driving memory for disclosure motivation.

It could also be the case that mediator and outcome variables could be reversed—that self-esteem mediates the effect of disclosure positivity on fear of disclosure. We tested this possibility in a separate model, which yielded similar fit to our preferred model (χ2 (2) = 2.66, n.s., CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, AIC = 26.60), although the lower AIC of our preferred model suggests that it offers a more parsimonious fit to the data than this alternative model. Further, in this alternative model, self-esteem did not mediate the effect of disclosure positivity on fear of disclosure.

Discussion

Interpersonal disclosure is an important part of the lives of those who live with a concealable stigmatized identity, and decisions to disclose for the first time can be some of the most difficult. Our data suggest that motivations for disclosure are one antecedent that can impact how first disclosure events unfold and that the degree to which people's first disclosure events are positive and supportive can have important implications for their long-term well-being because it can impact fear of disclosure. In doing so, our data provide new insight into the nature of disclosure processes themselves and advance research aimed at understanding the experiences of people who live with concealable stigmatized identities.

Data from this work indicate that motivations for disclosure can impact how disclosure events unfold which, in turn, can have consequences for long-term well-being. We drew on insights from Crocker and colleagues' ecosystem vs. egosystem motivational framework in order to examine how motivations can impact outcomes of disclosure (Crocker et al., 2008; Crocker, 2008). Our data indicate that participants who reported having an ecosystem motivation for disclosure—a motivation that is focused on how disclosure involves both the self and a disclosure confidant—also reported greater first disclosure positivity. These findings are in line with recent work by Garcia and Crocker (2008); however, whereas Garcia and Crocker's (2008) work demonstrates that motivations can impact the short-term effects of disclosure, we demonstrate that motivations also have the potential to impact long-term outcomes because they effect how the first disclosure event unfolds.

Consistent with previous work (e.g., Major et al., 1990), results from this study demonstrate that positive and supportive disclosure experiences can have long-term psychological benefits. Our data also reinforce the notion that disclosure may only yield psychological benefits to the extent that people feel supported and accepted when they make the difficult decision to talk to others about their concealable stigmatized identity (e.g., Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009). Despite the fact that only 11.5% of our sample reported neutral or negative first disclosure experiences, our data demonstrate that increasingly positive experiences can have benefits for self-esteem.

Our data indicate that one reason why first disclosure positivity can continue to influence well-being years after the event has occurred is because it impacts people's chronic fear of disclosure. That is, receiving support and positive feedback during the first time a stigmatized identity is disclosed may lead people to experience a greater sense of trust in others and a comfort in disclosing personal information. When people instead have a higher fear of disclosure, they may also experience less social support and more isolation (Rogers & Forbes, 1999). Of course, it is likely the case that there are additional or alternative mediating processes that affect the relationship between disclosure and well-being (Chaudoir & Fisher, in press). For example, disclosure may enhance group identification for these individuals, thereby providing a powerful buffer against the psychological costs of social devaluation (Crabtree, Haslam, Postmes, & Haslam, in press; Leach, Rodriguez Mosquera, Vliek, & Hirt, in press).

An important limitation of our study is its reliance on cross-sectional data and our limited ability to draw causal inferences. Thus, we cannot rule out the alternative conclusion from our data that current well-being impacted recall of the first disclosure event. However, given that our primary outcome measure, self-esteem, was not reliably associated with recall of the motivations for disclosure, we have some evidence to suggest that our interpretation of the data is plausible. Although several studies have examined the longitudinal psychological implications of chronic concealment of a stigmatized attribute such as HIV (e.g., Cole, Kemeny, Taylor, Visscher, & Fahey, 1996), no known longitudinal work addresses the long-term psychological consequences of a specific instance of disclosure, such as first disclosure experiences. Thus, future work that employs longitudinal methodology is desperately needed in order for researchers to begin to isolate the factors that affect these disclosure processes.

In sum, the results from this study provide new information about the processes that are involved in the disclosure of concealable stigmatized identities for the first time, and these results have both conceptual and applied implications. To our knowledge, this work is among the first to examine disclosure processes across a wide range of concealable stigmatized identities, an approach that may help researchers understand the common psychological processes involved in disclosure decisions and outcomes. Further, the current study provides new insights into disclosure as a dynamic psychological process and reiterates what practitioners and those living with concealable stigmatized identities already know quite intimately: Disclosing a concealable stigmatized identity for the first time is a tremendously complex process, and its effects can last long afterwards.

Table 2. Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ecosystem disclosure motivation | - | |||

| 2. First disclosure positivity | .16* | - | ||

| 3. Fear of disclosure | -.04 | -.31** | - | |

| 4. Self-esteem | -.05 | .22** | -.59** | - |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award individual pre-doctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health, 1F31MH080651, awarded to the first author. Results of this work were presented at the 7th biennial meeting of the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues in June 2008. We thank Shondell Diaz, Karen Grudzinski, Zahra Nims, and Sarah Pennington for help with data collection and coding.

References

- Ahrens CE, Campbell R, Ternier-Thames NK, Wasco SM, Sefl T. Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of rape survivors' first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CE. Being silenced: The impact of negative social reactions on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals KP, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:867–879. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision-making and post-disclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin. doi: 10.1037/a0018193. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Visscher BR, Fahey JL. Accelerated course of human immunodeficiency virus infection in gay men who conceal their homosexual identity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:219–231. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. Dealing with stigma through personal disclosure. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree JW, Haslam SA, Postmes T, Haslam C. Mental health support groups, stigma and self-esteem: Positive and negative implications of group identification. Journal of Social Issues in press. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. From egosystem to ecosystem: Implications for relationships, learning, and well-being. In: Wayment HA, Bauer JJ, editors. Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2008. pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Canevello A. Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:555–575. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Garcia JA, Nuer N. From egosystem to ecosystem in intergroup interactions: Implications for intergroup reconciliation. In: Nadler A, Malloy TE, Fisheres JD, editors. The social psychology of intergroup reconciliation. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele CM. Social stigma. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4th. McGraw Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Grzelak J. Self-disclosures: Origins, patterns and implications of openness in interpersonal relationships. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1979. Appropriateness of self-disclosure; pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Metts S, Petronio S, Margulis ST. Self-disclosure. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN. Reasons for HIV disclosure/nondisclosure in close relationships: Testing a model of HIV-disclosure decision making. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:747–767. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS. Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist. 1986;41:1040–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A, Roger D. Stress, social support and fear of disclosure. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Crocker J. Reasons for disclosing depression matter: The consequences of having egosystem and ecosystem goals. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Frey LR, Derlega VJ. Interpersonalizing AIDS: Attending to the personal and social relationships of individuals living with HIV and/or AIDS. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Leach CW, Rodriguez Mosquera PM, Vliek MLW, Hirt E. Group devaluation and group identification. Journal of Social Issues in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Ragan JD, Jones S. Talking facilitates cognitive-emotional processes of adaptation to an acute stressor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:499–508. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Cozzarelli C, Sciacchitano AM, Cooper ML, Testa M, Mueller PM. Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:452–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O'Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omarzu J. A disclosure decision model: Determining how and when individuals will self-disclose. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2000;4:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science. 1997;8:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM. Concealable versus conspicuous stigmatized identities. In: Levin S, van Laar C, editors. Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragins BR, Singh R, Cornwell JM. Making the invisible visible: Fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:1103–1118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RR, Kelly AE. Health effects of disclosing secrets to imagined accepting versus nonaccepting confidants. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:1023–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Smart L, Wegner DM. Covering up what can't be seen: Concealable stigma and mental control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:474–486. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:505–526. [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Predictors of disclosure of human immunovirus-positive serostatus among latino gay men. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:304–312. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]