Abstract

Effort is being expended in investigating efficiency measures (i.e., doing trials right) through achievement of accrual and endpoint goals for clinical trials. It is time to address the question of impact of such trials in addressing cancer critical needs through effectiveness measures (i.e., doing the right trials?)

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Schroen and colleagues1 point out that, in their data set, approximately one-third of NCI cooperative group Phase III trials close due to inadequate accrual and that about one-fourth of trial results are never published.

The discussion of achievement of trial accrual goals as a performance metric has been a vibrant one. Different researchers, using different data sets, different trial types and different definitions of “success” naturally arrive at different magnitudes of the problem, with estimates ranging from 22%2 to 38%3 of oncology trials closing with insufficient accruals. While the metric of publication of results has not had the same debate, the range of results for non-publication vary from 9.7%4 to 41%5 again using different data sets. There are varied interpretations of these findings, what has been agreed upon is that there is a strong need to improve performance and productivity of clinical trials.

If such metrics are to be useful in evaluating performance of oncology research, then clearly it is time for a concerted discussion on what standards should be applied and to what elements of the problem. One approach is to follow the method that National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Operational Efficiency Working Group (OEWG) accomplished with respect to time to open oncology trials.6 This effort brought together over 60 individuals, from the NCI, cooperative groups, cancer centers, the NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, statisticians, and patient advocates, all to focus on the issue of compressing the timeline to cancer clinical trial activation. OEWG created standards, metrics, and expected performance to those metrics, which are currently be utilized to evaluate cooperative groups trials. Additionally, it created a specific consequence for those trials that do not achieve the development timeline performance metric. Imagine what the impact if such standards could be generated for the issues of trial accrual performance or publication rates?

Let us give one example: what should be the standard definition of achievement of “accrual success”? Schroen et al.1 define accrual sufficiency based on evidence of addressing the primary endpoint through resulting publications. Korn et al2 utilize a threshold of ≥ 90% of the target accrual. Cheng et al.3 apply yet a different metric of 100% of minimum expected target accrual defined at the time of study inception, assuming that statisticians use this expected sample size to support the power the study. Clearly there is a need for better performance, but we must agree on a uniform definition before we can benchmark the efficiency of oncology clinical trials.

On a related note, efficiency is becoming increasingly important to the entire cancer clinical trial system with the flattening of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget since 2004. As highlighted in the Institute of Medicine report7 there are a wealth of opportunities to improve the clinical trial process with respect to such issues as streamlining trial opening, use of innovative trial designs, and improving the completion of trials. These aspects focus on what management researchers consider “doing things right”, i.e., efficient use of resources.

However, there is one recommendation of the IOM report that has been understudied, namely prioritization and selection of clinical trials. Again, using a management term, this is effectiveness or “doing the right things.” As the oncology community braces for major changes–through the consolidation of the cooperative group programs, the tsunami of potentially available data from biorepositiories and biomarker/genetic libraries, the use of adaptive trial designs and the implications from the upcoming national healthcare reform – measuring effectiveness of clinical research will be increasingly critical to sustaining the current progress of cancer research.

Like the complex discussions of efficiency metrics, such a discussion of effectiveness metrics will be lively. How should the portfolio of trials be balanced relative to cancer incidences, mortality rates, cancer severity, and relative quality-of-life? How should rare cancers be apportioned in an era of personalized medicine when every cancer might be considered “rare” due to biomarker identification? Should early-phase trials be prioritized within cancer types with few treatment options while larger late-phase trials be carried out for cancers with larger patient populations and multiple treatment options? And, linking efficiency metrics with effective metrics: should we match geographic cancer demographics to target specific types of trials in order to improve the likelihood of accrual success? Fundamentally, how do we know if we are effectively doing appropriate clinical research to accelerate the pace of change in the right direction?

While such discussions will be difficult and complicated, it is time for assessment and alignment of the entire portfolio of clinical trials being funded by governmental sources. Linking patient need with scientific discoveries with the strategic direction of clinical research and the desired portfolio of clinical trials can help define both areas for incremental progress and likely opportunities for major leaps forward.

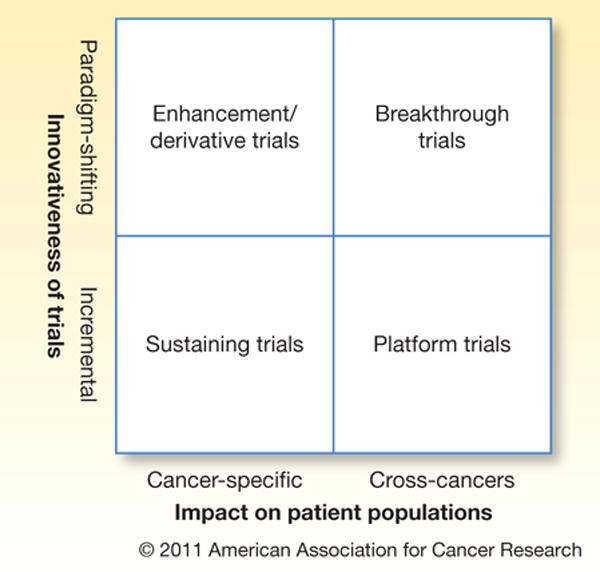

It is important to note that when developing such a portfolio of clinical trials that, by its very nature, a portfolio is a mix of different trial types, trial characteristics and potential trial impact. For example, one standard product development matrix approach8 divides a portfolio into breakthrough projects, platform projects, enhancement/derivative projects, and sustaining projects (figure 1). In the oncology clinical trial realm, an example breakthrough trial (project) would be a totally novel drug, focusing on a novel pathway, which could dramatically change how people with that type of cancer are treated. A platform trial (project) could be one where a drug that has been successfully used for one type of cancer is evaluated for use in a different type of cancer. Enhancement/Derivative trials (projects) could be a phase II trial that includes additional targeted biomarker screening to tailor cancer therapies and investigate outcomes. Finally, a sustaining trial would be one that would focuses on fine-tuning dosages or treatment cycles.

Figure 1.

Clinical trial portfolio matrix

While the exact mix of trials that are undertaken is intricate and fluid, it is important that this appraisal be attempted. Portfolio metrics of effectiveness can then evaluate the entire research portfolio allowing for the understanding of relative progress and productivity derived from clinical research. These metrics will be useful when considering how the national investment in clinical research aligns with the cancer burden across different cancer types, geographic disparities, and trends of longevity and quality-of-life.

It is important that both efficiency and effectiveness be done simultaneously. Efficiently completing clinical trials that only result in minor, non-sustainable incremental advancements might do little to benefit the overall progress in the search of improved cancer therapies. Conversely, clinical trials that are potentially paradigm-shifting can be fruitless and frustrating if they are continually obstructed by operational barriers9. What is needed are agreed upon efficiency and effectiveness measures to focus the limited resources to achieve the greatest return on the collective efforts of the oncology clinical research community.

References

- 1.Schroen AT, Petroni GR, Wang H, Thielen MJ, Gray R, Benedetti J, et al. Achieving Sufficient Accrual to Address the Primary Endpoint in Phase III Clinical Trials from US Cooperative Oncology Groups. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Mooney M, Abrams JS. Accrual Experience of National Cancer Institute Cooperative Group Phase III Trials Activated From 2000 to 2007. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:5197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng SK, Dietrich MS, Dilts DM. A sense of urgency: evaluating the link between clinical trial development time and the accrual performance of Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (NCI-CTEP) sponsored studies. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:5557. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam VC, Tannock IF, Massey C, Rauw J, Krzyzanowska MK. Compendium of Unpublished Phase III Trials in Oncology: Characteristics and Impact on Clinical Practice. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:3133. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey S, Scoggins J. Commentary: practicing on the tip of an information iceberg? Evidence of underpublication of registered clinical trials in oncology. The Oncologist. 2008;13:925. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Operational Working Group of the Clinical Trials and Translational Research Advisory Committee. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheelwright SC, Clark KB. Revolutionizing product development. Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilts DM, Sandler AB. Invisible Barriers to Clinical Trials: The Impact of Structural, Infrastructural, and Procedural Barriers to Opening Oncology Clinical Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]