Abstract

Background

Epigenetic marks are heritable, influenced by the environment, direct the maturation of T lymphocytes, and in mice enhance the development of allergic airway disease. Thus it is important to define epigenetic alterations in asthmatic populations.

Objective

We hypothesize that epigenetic alterations in circulating PBMCs are associated with allergic asthma.

Methods

We compared DNA methylation patterns and gene expression in inner-city children with persistent atopic asthma versus healthy control subjects by using DNA and RNA from PBMCs. Results were validated in an independent population of asthmatic patients.

Results

Comparing asthmatic patients (n = 97) with control subjects (n = 97), we identified 81 regions that were differentially methylated. Several immune genes were hypomethylated in asthma, including IL13, RUNX3, and specific genes relevant to T lymphocytes (TIGIT). Among asthmatic patients, 11 differentially methylated regions were associated with higher serum IgE concentrations, and 16 were associated with percent predicted FEV1. Hypomethylated and hypermethylated regions were associated with increased and decreased gene expression, respectively (P < .6 × 10−11 for asthma and P < .01 for IgE). We further explored the relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression using an integrative analysis and identified additional candidates relevant to asthma (IL4 and ST2). Methylation marks involved in T-cell maturation (RUNX3), TH2 immunity (IL4), and oxidative stress (catalase) were validated in an independent asthmatic cohort of children living in the inner city.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that DNA methylation marks in specific gene loci are associated with asthma and suggest that epigenetic changes might play a role in establishing the immune phenotype associated with asthma.

Keywords: DNA methylation, atopic asthma, epigenetics, TH2 immunity, inner city

Asthma can be inherited and is affected by environmental exposures. To date, genome-wide linkage and association studies have identified more than 100 asthma-associated gene variants.1,2 However, sequence variants explain less than 10% of the risk of having asthma3, and several studies have shown that the risk of transmission of atopic disease from an affected mother is approximately 4 times higher than that from an affected father.4 Because epigenetic marks are also heritable and can account for parent-of-origin patterns of inheritance5, it is logical to speculate that epigenetic marks play a role in the transmission of asthma.6 Furthermore, although it is well established that asthma risk and severity are affected by specific environmental exposures, the epigenome can be altered by many of these environmental exposures, and these environmentally induced epigenomic changes often lead to rapid and persistent changes in gene expression.7 For example, in utero exposure to tobacco smoke is associated with childhood asthma, and this exposure can modify gene expression through DNA methylation. 8,9, In mice we have demonstrated that in utero supplementation with methyl donors alters locus-specific DNA methylation and predisposes mice to allergic airway disease by directing the differentiation of T lymphocytes, skewing toward a TH2 phenotype.10 Importantly, epigenetic mechanisms have been shown to specifically affect the expression of transcription factors involved in the development of mature T lymphocytes (TH1, TH2, and regulatory T cells),11–13 providing a potential mechanism that links heritability, the environment, immune biology, and asthma.14,15 In candidate gene studies DNA methylation has been shown to be related to childhood asthma in peripheral blood cells, 16,17 buccal cells18, or nasal epithelia.19 Thus epigenetic marks represent logical biological changes to pursue when considering the cause and pathogenesis of asthma.

Because black children and families living in poverty are at particularly high risk of asthma,20 we have investigated the relationship between asthma and DNA methylation in African American children residing in the inner city. We hypothesize that epigenetic marks in circulating PBMCs are associated with allergic asthma.

METHODS

Study population

Our study population consisted of inner-city children aged 6 to 12 years with atopy and persistent asthma (cases, n = 97) and without atopy or asthma (healthy control subjects, n = 97) recruited by 6 sites of the Inner-City Asthma Consortium from census tracts that contain at least 20% of households living at less than the US government–defined poverty level.21 All subjects reported being African American, Hispanic with Dominican/Haitian background, or both. The validation population consisted of 101 African Americans between 6 and 12 years of age with atopic asthma collected by the Inner-City Asthma Consortium independent of the primary study population. Please refer to the Methods section in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for more information on selection of the study population.

DNA methylation and gene expression data collection

DNA methylation in PBMCs was measured on Illumina’s Infinium Human Methylation 450k BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, Calif) and validated by using pyrosequencing with custom-designed primers (see Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Gene expression was assessed on Nimblegen Human Gene Expression arrays (12x135k). Please refer to the Methods section in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for details of the protocols used for data collection.

Data quality controls

We first examined the quality control figures created by using the minfi R package for the 450k data.22 We observed a strong bimodal distribution of methylation values in the 450k data, as previously observed.23 Further data quality for Illumina 450k and expression arrays was assessed by using principal components analysis (PCA). The principal components were examined for correlation with all clinical/demographic and laboratory data to identify observable batch effects or covariates that explained variation (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).24 As a result of PCA, we removed one outlier sample from the 450k methylation data, whereas no outlier samples were identified in expression arrays. Although no laboratory variables were significantly correlated with principal components in the methylation data set, we included 4 laboratory variables in the expression analysis (labeling, date and concentration of whole transcriptome–amplified RNA, and hybridization date) because of their significant correlation with principal components (PCs). Of all demographic and clinical data, age and sex are strongly associated with the top PCs in both methylation and expression data sets. Although race/ethnicity is not associated with the top PCs, we included these covariates in the statistical model because of their known associations with DNA methylation.25

In addition to PCA, probabilistic estimation of expression residuals (PEER) factors26 were estimated to account for unknown batch effects. The number of PEER factors included in downstream analyses was 1 for 450k and 5 for gene expression. The number of PEER factors was based on the inflection point seen on visual inspection of the weighting of the inferred factors.26

Overview of statistical analyses

The goal of our analyses was to determine whether DNA methylation and gene expression changes are associated with asthma, IgE levels, and percent predicted FEV1. Cases and control subjects were used to determine whether methylation marks were associated with asthma, whereas the other 2 outcomes (IgE level and FEV1) were analyzed only within asthmatic patients. We first identified differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with atopic asthma. For asthma-associated DMRs, we explored whether the DMRs were influenced by the cell composition of PBMCs. Next, we explored the relationship between PBMC gene expression and asthma, IgE levels, and percent predicted FEV1 using the same approach outlined above. Lastly, we investigated the relationship of DNA methylation to gene expression in PBMCs. DNA methylation–gene expression relationships were examined by using (1) plots of gene expression versus DMRs and analysis of enrichment for inverse correlations of DMRs and gene expression and (2) integrated analysis of single-probe DNA methylation and gene expression. The second approach focused on single methylation probes as opposed to DMRs because of the limitation of statistical methodologies; all available methods for integrative analysis are limited to analysis of 1 methylation and 1 expression probe in statistical models.

Our rationale for inclusion of DMRs in this analysis is 4-fold: (1) identification of regions as opposed to single CpGs is conceptually consistent with what is known about DNA methylation patterns in the human genome27; (2) DMRs increase power to detect associations28,29; (3) DMRs allow for analysis of all probes on the array, which, in turn, facilitates finding regions of interest; and (4) DMR analysis has been used successfully in patients with other diseases. 30–32 The alternative to DMR analysis is to remove between 20,000 and 140,000 probes from the analysis depending on the required frequency and distance of a variant in the African American population from the CpG motif. It is known that single nucleotide polymorphisms contained in the Infinium probes can affect binding and result in spurious methylation measurements33; however, our combined P value method34 requires 2 or more adjacent probes and, as such, minimized this effect in the methylation analysis.

Statistical analyses of DNA methylation data

Data from the methylation array were normalized with the SWAN method35 contained in the R package minfi,36 and the normalized M-values were used in all downstream analyses. β Values (which range from 0–1) of all of the probes within each DMR are plotted in Figs 1, A, and 2, whereas average β values across the DMR are reported in Fig 3, A and B, and the supplemental tables. β Values are biologically intuitive interpretations of percentage methylation changes on the 0- to 1-point scale corresponding to 0% to 100% methylation.

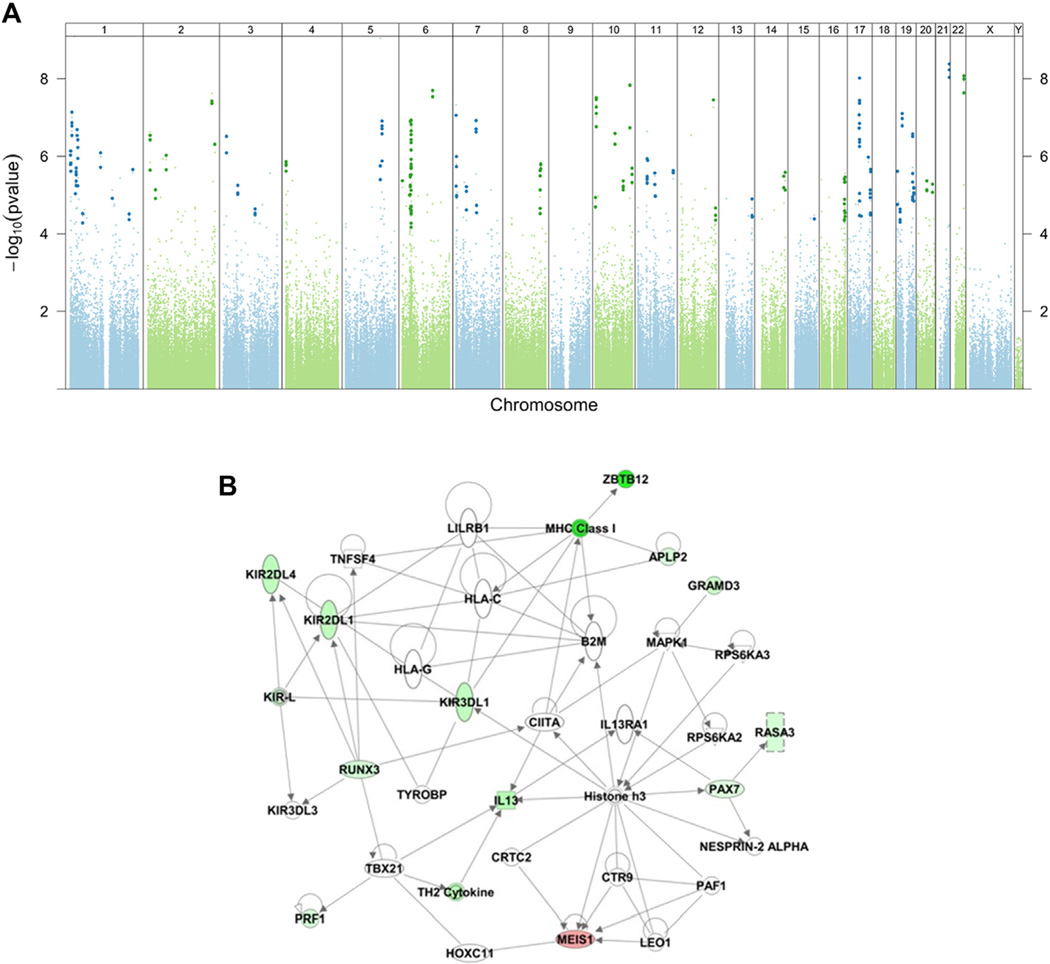

FIG 1.

DMRs are associated with asthma after controlling for age, sex, race, technical variables, and batch effects. A, Manhattan plot of adjusted P values for disease status (asthma/control) from the linear model. Each dot represents a P value for a probe on the Illumina 450k array that has been adjusted by the significance of neighboring probes within 300 bases according to their correlation. Probes within statistically significant DMRs are identified by a darker and slightly larger symbol after adjustment for genome-wide comparisons. B, A representative transcriptional network of genes with associated DMRs from Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Network analysis was performed with only direct interactions (solid lines) and networks with a score of greater than 20. Genes are intensity colored red (hypermethylated) or green (hypomethylated). Horizontal ellipse, Transcriptional regulator; square, cytokine; double circle, group/complex; triangle, phosphatase; vertical ellipse, transmembrane receptor; rectangle, ion channel.

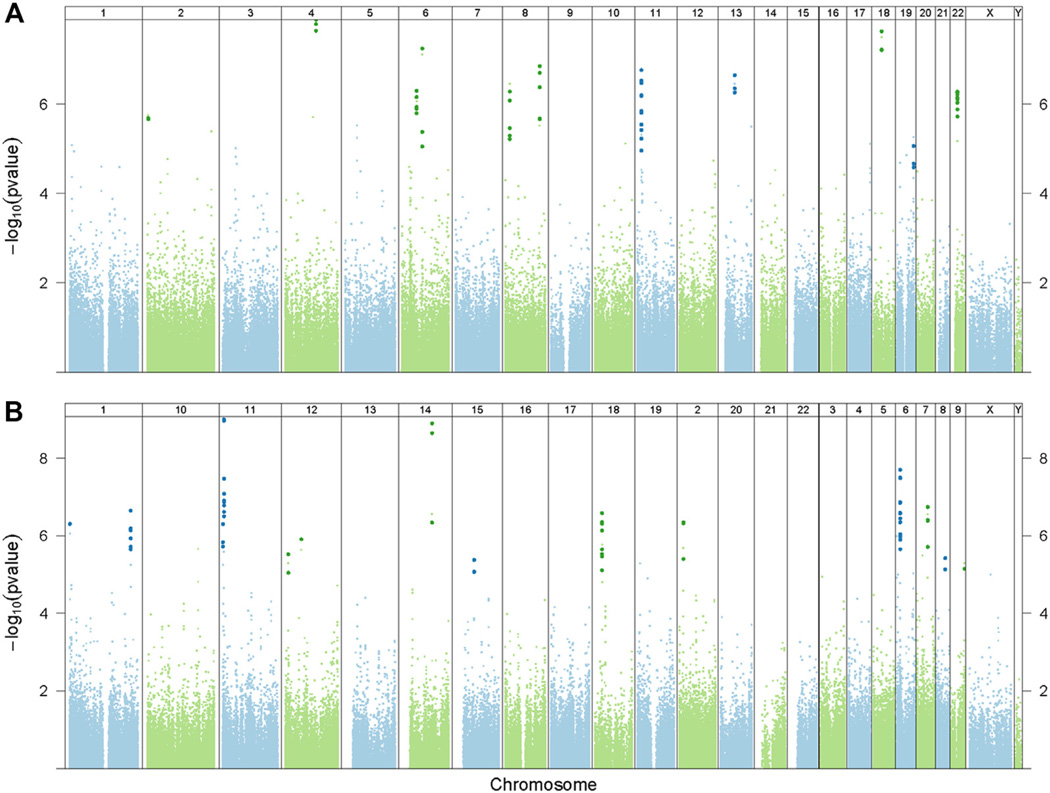

FIG 2.

Differentially methylated marks are associated with higher total serum IgE concentrations (A) and percent predicted FEV1 (B) after controlling for age, sex, race, technical variables, and batch effects among the asthmatic patients. Manhattan plots were constructed in the same fashion as in Fig 1, A Probes within statistically significant DMRs are identified by a darker and slightly larger symbol after adjustment for genome-wide comparisons.

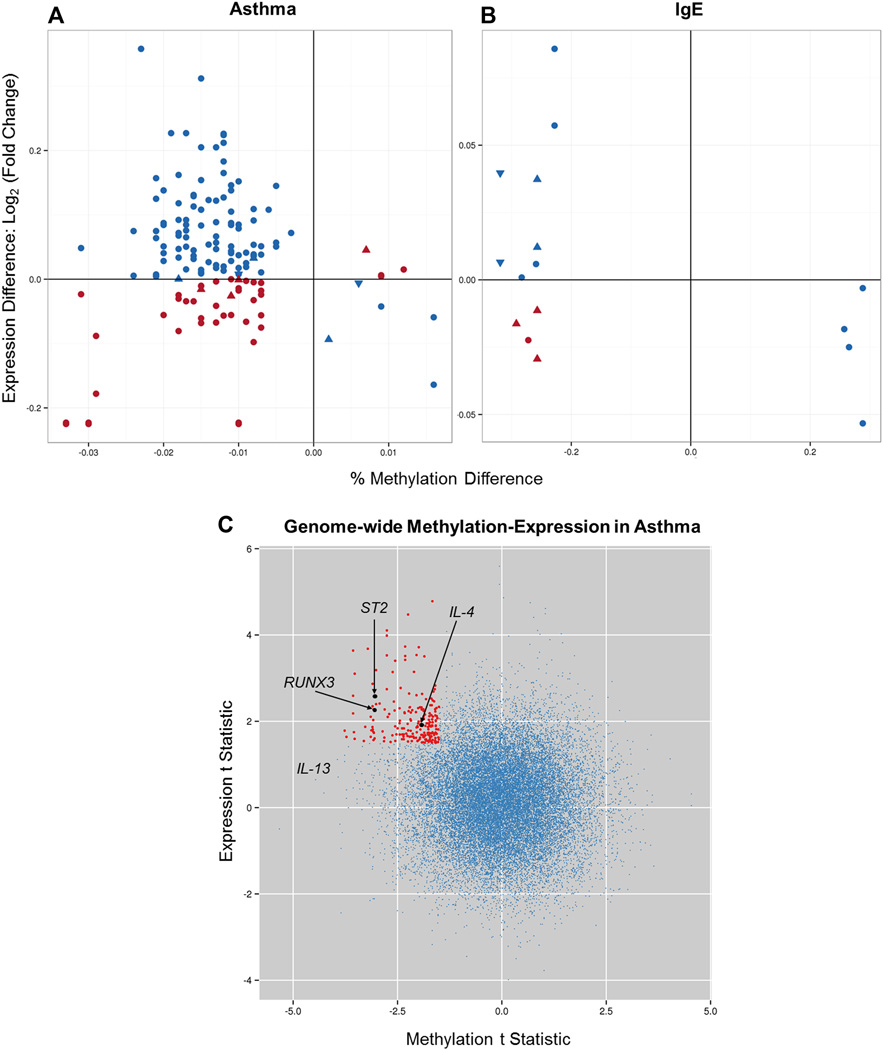

FIG 3.

Expression changes in genes within 3 kb of the nearest DMR associated with asthma in the entire study population (A), IgE levels among asthmatic patients (B), and genome-wide methylation expression in asthmatic patients (C). Fig 3, A, x-axis, The methylation difference is represented by the mean percentage methylation difference in asthmatic patients compared with control subjects. Fig 3, A, y-axis, The expression difference is represented by the mean fold change in asthmatic patients compared with control subjects (on the log base 2 scale). Fig 3, B, The percentage methylation difference on the x-axis is represented by the mean correlation coefficient between IgE and methylation in asthmatic patients. The y-axis is represented by the slope of the IgE covariate in the linear model for expression in asthmatic patients. Blue symbols represent hypomethylated genes associated with increased gene expression, as well as some hypermethylated genes associated with decreased gene expression. Red symbols represent methylation changes that were not associated with expected gene expression differences. Upward triangles indicate DMR location upstream of the gene, circles represent DMRs in the gene body, and downward triangles refer to DMRs downstream of the gene. In Fig 3, C, the t statistic for expression change of all genes in the genome in asthmatic patients compared with control subjects from PBMCs is plotted against the t statistic for methylation changes in these genes (single CpG within the 3-kb promoter). Red dots represent the 207 genes with posterior probability from the joint model of methylation and expression of greater than 0.95 (corresponding to q < 0.05), a methylation t statistic of less than 21.5, and an expression t statistic of greater than 1.5 (see Table E10, A). Additionally, 82 genes have posterior probability of greater than 0.95, a methylation t statistic of less than 21.5, and an expression t statistic of less than 21.5 (lower left quadrant, see Table E10, B). No significant expression/methylation changes were identified in the right 2 quadrants on this plot.

We performed methylation array analysis in 3 steps. In brief, these are (1) infer PEER factors, (2) fit linear models with limma,37 and use comb-p34 to identify DMRs from the P values reported by limma. Limma was used to fit linear models because it allows us to use the moderated t statistic, which has been shown to be more powerful in microarray experiments than the standard t statistic. Our models included a clinical covariate of interest (asthma, FEV1 asthma subtype, or IgE level), demographic covariates that are known to affect DNA methylation (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), and 1 PEER factor to account for unobserved batch effects (with details of statistical models included in Table E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org):

Methylation ~ Asthma + Age + Sex + Race/ethnicity + Peer(1).

Methylation ~ ln(IgE) + Age + Sex + Race/ethnicity + Peer(1).

Methylation ~ FEV1 (% predicted) + Age + Sex + Race/ethnicity + Peer(1).

In these models Peer(1) refers to the first PEER component. Cases and control subjects were used in the first model, whereas cases only were used in the second and third models. DMRs were identified from linear model P values by using comb-p,34 with a window size of 300 bases and containing a minimum of 2 probes.

The identification of DMRs is described in detail in Pedersen et al34 and outlined in the diagram in Fig E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org. Comb-p takes as input unadjusted P values for each probe on the array from limma and calculates an adjusted P value for each probe that accounts for the local correlation and the P values of neighboring probes within 300 bases. Probe-level P values are then adjusted by using the Benjamini-Hochberg methodology,38 resulting in multiple testing–corrected P values for individual probes that are influenced by their neighboring CpG motifs. Next, comb-p finds regions or DMRs and calculates P values for the regions based on correlation (SLK P value).39 Finally, the region P values are adjusted for multiple testing by using the Sidak correction40 based on the size of the region and number of possible regions of that size, such that larger regions undergo less stringent correction because there are fewer possible large regions (SLK-Sidak P value). DMRs were annotated with the CruzDB tool.41

For validation, we analyzed pyrosequencing data from the discovery and validation cohorts using the 1-sided t test for cases versus control subjects and considered DMRs validated if they had P values of less than .05.

Estimate of cell proportions from DNA methylation data

We also analyzed Illumina 450k methylation data to estimate proportions of different mononuclear cell populations and contaminating granulocytes.42 Using our methylation β values and the 500 informative probes reported by Houseman et al,42 we estimated the coefficients for the 6 cell types: 5 monocyte cell types (B lymphocytes, CD4+ T lymphocytes, CD8+ T lymphocytes, monocytes, and natural killer [NK] cells) and granulocyte contamination. We then used penalized regression to regress out the cell types and obtain a β value that represents the average cell. This process is encapsulated by the single R function adjust.beta (https://gist.github.com/brentp/5058805#file-houseman-r). We then logit transformed the adjusted β value to determine the M value and ran the model to determine which of the methylation differences were independent of cell type differences.

Statistical analyses of gene expression data

Intensity data from the Nimblegen DEVA software were log2 transformed and normalized by using RMA with the oligo R package.43 The R package limma37 was used to fit linear models for expression data, and P values were based on the moderated t statistic. For expression analysis, we used a model that incorporates clinical covariate of interest (asthma, ln [IgE], or percent predicted FEV1), demographic covariates that are known to affect expression (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), observable batch effects from PCA (labeling, hybridization date, WTA date, and WTA RNA concentration), and 5 PEER factors. The models for expression are presented in Table E3.

Correlation analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression

To understand the relationship of DMRs with gene expression changes, we considered inversely correlated (canonical) versus directly correlated pairs, limiting the analysis to genes within 3 kb of a DMR. We calculated the enrichment of inversely correlated pairs in relation to all pairs using the binomial test.

Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and expression

To integrate the expression and methylation data, we used LCMix, which was shown to be effective at identifying target genes in real and simulated data sets by combining information from disparate data sets.44 LCMix requires a 1:1 relation between the input data sets, and therefore we limited our analysis to expression probes that had a methylation probe upstream within 3 kb of the transcription start site (23,848 genes). We then determined the number of components for the marginal fits to methylation and expression using integrated classification likelihood-Bayesian information criterion,45 as suggested in Dvorkin et al.44 Using those component numbers, we then performed joint fit using the chained topology (methylation and expression), 2 hidden components, and the Pearson type VII family.

Pathway and network analysis

We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis46 to identify protein-protein networks and enriched biofunctions in the data sets (using the Fisher exact test).

RESULTS

The study groups (97 healthy control subjects and 97 patients with atopic asthma) were selected from a larger population of potential study subjects who were specifically screened for this project (see Table E4 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). When compared with control subjects, asthmatic children were more often male, more often exposed to damp home conditions, and less often exposed to gas stoves (Table I). Per study design, all asthmatic patients were atopic and had significant airflow limitation, as indicated by their total IgE levels and spirometric parameters (Table I).

TABLE I.

Demographic and clinical features of asthmatic patients and control subjects

| Asthmatic patients (n 5 97) |

Control subjects (n 5 97) |

P value* | Validation asthmatic population (n 5 101) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | ||||

| Boston | 23 (23.7%) | 31 (32.0%) | <.01† | 13 (12.9%) |

| Dallas | 8 (8.2%) | 2 (2.1%) | 10 (9.9%) | |

| Denver | 28 (28.9%) | 13 (13.4%) | 4 (4.0%) | |

| Detroit | 4 (4.1%) | 6 (6.2%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| New York | 22 (22.7%) | 14 (14.4%) | 6 (5.9%) | |

| Washington, DC | 12 (12.4%) | 31 (32.0%) | 9 (8.9%) | |

| Baltimore | – | – | 28 (27.7%) | |

| Chicago | – | – | 10 (9.9%) | |

| Cincinnati | – | – | 9 (8.9%) | |

| Age at recruitment (y) | 9.0 (8.0–11.0) | 9.0 (8.0–11.0) | .76‡ | 9.0 (8.0–11.0) |

| Sex (male) | 56 (57.7%) | 41 (42.3%) | .03† | 64 (63.4%) |

| Participant race: African American (yes) | 82 (84.5%) | 86 (88.7%) | .40† | 101 (100.0%) |

| Participant race: Hispanic or Latino (yes) | 26 (26.8%) | 15 (15.5%) | .05† | 0 (0.0%) |

| How often exposed to smokers: daily | 26 (26.8%) | 25 (25.8%) | .85† | 22 (21.8%) |

| Dog living in the home in the last 6 mo (yes) | 24 (24.7%) | 22 (22.7%) | .74† | 24 (23.8%) |

| Cat living in the home in the last 6 mo (yes) | 15 (15.5%) | 24 (24.7%) | .11† | 12 (11.9%) |

| Any water/dampness in the last 12 mo (yes) | 31 (32.0%) | 16 (16.5%) | .01† | 30 (29.7%) |

| Gas stove, gas range, or gas oven (yes) | 55 (56.7%) | 69 (71.1%) | .04† | 61 (60.4%) |

| Allergic to any indoor allergen (yes) | 97 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | § | 96 (95.1%) |

| Cockroach IgE (IU/mL) | 0.34 (0.34–1.65) | 0.34 (0.34–0.34) | § | 0.62 (0.34–10.0) |

| Total IgE (kU/L) | 408.5 (189.0–951.0) | 29.0 (15.0–58.0) | § | 481.0 (167.0–1264.0) |

| Baseline: FEV1 (% predicted) | 90.9 ± 16.7 | 103.0 ± 10.3 | § | 93.9 ± 19.3 |

| Baseline: FEV1/FVC ratio | 75.5 ± 9.7 | 84.4 ±6.1 | § | 77.5 ± 10.2 |

| Asthma medications | ||||

| Albuterol | 95 (97.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | § | 101 (100.0%) |

| Inhaled steroids | 84 (86.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 84 (83.2%) | |

| Montelukast | 38 (39.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (8.9%) |

Data are presented as means ± SDs, medians (IQRs), or numbers (percentages).

FVC, Forced vital capacity.

P values were calculated with the use of the x test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

χ2 Test.

Rank sum test.

By protocol design.

Comparing asthmatic patients with control subjects and adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and unknown batch effects (the statistical model is shown in Table E3),34 we identified 81 DMRs (Fig 1, A). Seventy-three DMRs were hypomethylated in asthmatic patients compared with control subjects, and 8 were hypermethylated (Table II). Several genes involved in T-lymphocyte biology were hypomethylated in asthmatic patients, including IL13, runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3), and specific genes involved in the maturation and function of NK cells (KIR2DL4, KIR2DL3, KIR3DL1, and KLRD1) and T lymphocytes (TIGIT). Many of the genes associated with the 81 DMRs are components of regulatory networks that have been traditionally associated with asthma (Fig 1, B, and Table II, with remaining DMR regulatory networks presented in Fig E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The most DMRs are near genes that have not been previously implicated in asthma but are plausible asthma candidates, including alkaline phosphatase (ALPL), a gene with a role in modulating host-bacterial interactions by dephosphorylating LPS,47 and Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6), a transcriptional activator with a recently established role in activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase 1 during influenza A virus infection48 and activation of TGF-β during human respiratory syncytial virus infection.49

TABLE II.

DMRs associated with asthma at an SLK-Sidak P value of less than .05

| Chromosome | Start | End | No. of probes |

Asthma SLK P value |

Asthma SLK-Sidak P value |

Gene | Location | CpG island distance |

Methylation difference (asthma- control [%]) |

FEV1 P value |

IgE P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr1 | 1091164 | 1091325 | 4 | 5.59E-07 | .00168 | CS444397 | 1075 | 717 | −0.012 | .003504 | |

| chr1 | 2220460 | 2220783 | 4 | 4.52E-07 | .00068 | SKI | Intron | 0 | −0.015 | ||

| chr1 | 6263726 | 6263914 | 4 | 3.79E-08 | 9.79E-05 | ACOT7 | Exon;intron;nc_ exon;nc_intron |

0 | −0.011 | ||

| chr1 | 6277594 | 6277647 | 2 | 1.41E-07 | .0013 | ACOT7 | Exon;intron;nc_ exon;nc_intron |

0 | −0.02 | .03596 | |

| chr1 | 15264894 | 15265020 | 2 | 4.38E-10 | 1.69E-06 | LOC391005 | Intron;utr3 | 0 | −0.029 | .03778 | |

| chr1 | 18883602 | 18883759 | 2 | 3.83E-06 | .01177 | PAX7 | Intron | 0 | −0.017 | ||

| chr1 | 21750110 | 21750368 | 5 | 3.59E-06 | .00673 | ALPL | utr5_intron | 23,263 | −0.01 | ||

| chr1 | 21773573 | 21773847 | 3 | 3.79E-06 | .00668 | ALPL | Intron | 0 | −0.03 | ||

| chr1 | 25113451 | 25113525 | 3 | 1.63E-07 | .00107 | RUNX3 | Intron | 0 | −0.018 | ||

| chr1 | 27555725 | 27556088 | 5 | 1.96E-07 | .00026 | MAP3K6 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.018 | ||

| chr1 | 45046081 | 45046267 | 3 | 1.74E-05 | .04438 | TCTEX1D4 | −537 | 1,268 | 0.006 | .01963 | |

| chr1 | 110108029 | 110108165 | 3 | 5.01E-07 | .00179 | EPS8L3 | utr5 | 23,218 | −0.01 | .01368 | |

| chr1 | 152566740 | 152566865 | 2 | 5.46E-06 | .021 | ATP8B2 | utr5_intron | 807 | 0.012 | .03256 | |

| chr1 | 213807046 | 213807324 | 3 | 2.66E-05 | .0453 | KCTD3 | 34 | 0 | 0.002 | ||

| chr1 | 227230174 | 227230200 | 2 | 2.00E-06 | .03665 | AX748369 | −110597 | 119,496 | 0.01 | ||

| chr2 | 8339686 | 8339783 | 3 | 9.66E-08 | .00048 | LINC00299 | nc_intron | 77,665 | −0.019 | .03115 | |

| chr2 | 8340572 | 8340606 | 2 | 1.02E-06 | .01438 | LINC00299 | nc_intron | 76,842 | −0.017 | ||

| chr2 | 27652710 | 27652915 | 3 | 7.47E-06 | .01754 | C2orf16 | utr5 | 6,296 | −0.013 | ||

| chr2 | 66518038 | 66518302 | 3 | 4.82E-07 | .00089 | MEIS1 | Intron | 1 | 0.009 | ||

| chr2 | 232101307 | 232101500 | 3 | 1.15E-08 | 2.90E-05 | NMUR1 | Exon | 0 | −0.018 | .0002612 | |

| chr2 | 242516227 | 242516284 | 2 | 5.56E-07 | .00472 | AK097934 | 45223 | 707 | −0.025 | ||

| chr3 | 11626535 | 11626881 | 3 | 1.25E-07 | .00018 | VGLL4 | Intron | 0 | −0.012 | ||

| chr3 | 52787406 | 52787560 | 4 | 5.39E-06 | .01686 | ITIH1 | Exon;nc_exon | 7,238 | −0.013 | ||

| chr3 | 115495348 | 115495602 | 4 | 1.67E-05 | .03144 | TIGIT | Exon;utr5 | 16,590 | −0.01 | ||

| chr4 | 1233848 | 1234086 | 7 | 5.29E-07 | .00108 | AK125775 | nc_exon | 0 | −0.018 | ||

| chr5 | 125723585 | 125723747 | 3 | 3.32E-10 | 9.96E-07 | GRAMD3 | 63253 | 63,229 | −0.012 | .03647 | |

| chr5 | 132021512 | 132021960 | 6 | 5.34E-08 | 5.79E-05 | IL13 | Exon;intron;utr5 | 1,309 | −0.008 | ||

| chr6 | 458210 | 458297 | 2 | 4.91E-06 | .027 | EXOC2 | Intron | 2,395 | −0.014 | ||

| chr6 | 26334181 | 26334235 | 2 | 1.41E-07 | .00126 | HIST1H3F | utr3 | 0 | −0.009 | ||

| chr6 | 29019737 | 29020145 | 10 | 8.39E-07 | .001 | TRIM27 | −19990 | 0 | 0.017 | ||

| chr6 | 31954747 | 31955007 | 10 | 6.90E-06 | .01281 | SLC44A4 | utr5 | 0 | −0.015 | ||

| chr6 | 31975676 | 31976004 | 20 | 2.89E-08 | 4.28E-05 | C2;ZBTB12 | Exon;utr3;utr5_ intron |

0 | −0.015 | .01655 | |

| chr6 | 109881430 | 109881854 | 3 | 1.42E-08 | 1.62E-05 | MICAL1 | Exon;intron | 942 | −0.008 | ||

| chr7 | 888576 | 888761 | 3 | 3.47E-08 | 9.11E-05 | GET4;SUN1 | Intron;nc_intron | 0 | −0.005 | ||

| chr7 | 2056125 | 2056406 | 3 | 7.89E-07 | .00136 |

MAD1; MAD1L1 |

Intron | 0 | −0.016 | .01102 | |

| chr7 | 2695301 | 2695438 | 3 | 8.55E-06 | .02983 | AMZ1 | utr5_intron | 0 | −0.013 | ||

| chr7 | 38323253 | 38323572 | 4 | 2.71E-06 | .00412 | TCRg;TRGV9 | Exon;intron;nc_ exon |

5,468 | −0.021 | ||

| chr7 | 73283658 | 73283902 | 4 | 9.19E-08 | .00018 | RFC2 | utr3 | 0 | −0.017 | ||

| chr7 | 74890962 | 74891132 | 3 | 1.05E-05 | .0296 | POM121C | Intron | 0 | −0.01 | .00866 | |

| chr8 | 125532162 | 125532491 | 6 | 1.73E-06 | .00255 | TRMT12 | Exon;utr5 | 0 | 0.016 | 9.29E-08 | |

| chr8 | 127638762 | 127638859 | 4 | 8.24E-07 | .00412 | FAM84B | Exon;utr5 | 0 | −0.008 | .0131 | |

| chr10 | 848816 | 848923 | 3 | 8.24E-06 | .0367 | LARP5 | Exon;utr3 | 1,721 | −0.012 | .03864 | |

| chr10 | 3813757 | 3814016 | 5 | 8.39E-09 | 1.57E-05 | KLF6 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.021 | ||

| chr10 | 3814386 | 3814687 | 4 | 3.08E-08 | 4.96E-05 | KLF6 | Exon;intron | 88 | −0.024 | ||

| chr10 | 72030353 | 72030454 | 3 | 1.27E-07 | .00061 | PRF1 | Exon | 0 | −0.015 | .01763 | |

| chr10 | 101814909 | 101815175 | 5 | 3.92E-06 | .00713 | CPN1 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.016 | ||

| chr10 | 126320834 | 126321170 | 4 | 2.03E-07 | .00029 | FAM53B | Intron | 246 | −0.016 | .0125 | |

| chr10 | 134072207 | 134072497 | 4 | 2.63E-06 | .0044 | PWWP2B | Intron;utr3_intron | 0 | −0.009 | .00745 | |

| chr11 | 34416873 | 34417133 | 7 | 7.88E-07 | .00147 | CAT | utr5 | 0 | −0.018 | .01748 | |

| chr11 | 36377805 | 36377877 | 2 | 7.07E-07 | .00475 | FLJ14213 | Intron;utr5_intron | 21,831 | −0.01 | .006936 | |

| chr11 | 62378748 | 62378810 | 3 | 1.62E-06 | .01262 | SNHG1 | nc_intron | 696 | 0.007 | ||

| chr11 | 64289922 | 64290199 | 3 | 3.71E-06 | .00647 | SF1 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.009 | .02808 | |

| chr11 | 129485687 | 129485739 | 3 | 2.10E-06 | .01937 | APLP2 | Exon;utr5_intron | 13,029 | −0.007 | .0003045 | |

| chr12 | 122162107 | 122162366 | 2 | 3.43E-08 | 6.43E-05 | PITPNM2 | utr5_intron | 38,347 | −0.021 | ||

| chr12 | 130134393 | 130134600 | 4 | 1.33E-05 | .03062 | GPR133 | Intron;utr5_intron | 0 | −0.006 | ||

| chr13 | 113220890 | 113221025 | 3 | 1.19E-05 | .04192 | TMCO3 | Intron | 0 | −0.015 | .0001811 | |

| chr13 | 113825056 | 113825282 | 3 | 1.34E-05 | .02828 | RASA3 | Intron;utr5_intron | 0 | −0.007 | ||

| chr14 | 98857115 | 98857373 | 3 | 3.11E-06 | .00583 | BCL11B | −49540 | 0 | −0.015 | ||

| chr14 | 104255101 | 104255221 | 3 | 2.80E-06 | .01125 | INF2 | Intron;nc_intron; utr3_intron |

0 | −0.013 | ||

| chr15 | 89170960 | 89171237 | 2 | 2.72E-05 | .0465 | BLM | − 11270 | 0 | −0.013 | .0374 | |

| chr16 | 84108978 | 84109249 | 3 | 1.59E-06 | .00285 | KIAA0182 | 93281 | 0 | −0.01 | ||

| chr16 | 84233792 | 84234027 | 4 | 1.86E-05 | .03767 | KIAA0182 | Intron;utr5_intron | 0 | −0.011 | ||

| chr16 | 85272036 | 85272335 | 4 | 1.63E-06 | .00264 | BC041439 | 39457 | 0 | −0.012 | ||

| chr16 | 87075079 | 87075362 | 3 | 1.39E-05 | .02358 | ZFPM1 | Intron | 1,919 | −0.003 | ||

| chr16 | 87085565 | 87085738 | 3 | 1.59E-06 | .00444 | ZFPM1 | Intron | 0 | −0.018 | ||

| chr17 | 37379133 | 37379307 | 3 | 5.59E-08 | .00016 | CNP | Exon | 0 | −0.015 | .00594 | |

| chr17 | 38531660 | 38531955 | 12 | 1.59E-08 | 2.62E-05 | NBR2 | nc_intron | 0 | −0.021 | .02746 | |

| chr17 | 44652266 | 44652511 | 2 | 1.18E-05 | .02301 | ABI3 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.014 | .002791 | |

| chr17 | 70268887 | 70268897 | 2 | 9.75E-07 | .04621 | SLC9A3R1 | Intron;nc_intron | 11,350 | −0.017 | .005602 | |

| chr17 | 77226056 | 77226266 | 4 | 4.00E-06 | .00921 | TSPAN10 | nc_exon;utr3 | 0 | −0.031 | ||

| chr17 | 77986792 | 77986955 | 4 | 1.35E-05 | .03938 | HEXDC | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.011 | .0008078 | |

| chr17 | 78474047 | 78474241 | 3 | 1.15E-06 | .00288 | TBCD | Intron | 0 | −0.013 | ||

| chr19 | 1207998 | 1208217 | 3 | 1.38E-05 | .03013 | MIDN | Exon | 0 | −0.007 | ||

| chr19 | 10523581 | 10523782 | 5 | 1.46E-05 | .03466 | ATG4D | Exon;intron;nc_ exon;nc_intron; utr5 |

3,012 | −0.008 | ||

| chr19 | 18121329 | 18121515 | 4 | 3.31E-08 | 8.64E-05 | MAST3 | Exon | 0 | −0.016 | ||

| chr19 | 55911909 | 55912349 | 9 | 1.02E-07 | .00011 | SHANK1 | Exon;utr5 | 0 | −0.008 | 7.29E-06 | |

| chr19 | 60006690 | 60006895 | 6 | 3.44E-06 | .00812 |

KIR2DL4; KIR2DS2; KIR3DL1 |

Intron;utr5 | 12,754 | −0.012 | ||

| chr20 | 34937784 | 34937967 | 4 | 1.33E-06 | .00353 | C20orf118 | 17 | 11,603 | −0.008 | ||

| chr20 | 55416108 | 55416384 | 3 | 3.23E-06 | .00566 | RBM38 | Exon;utr3 | 0 | −0.012 | .0143 | |

| chr21 | 46670037 | 46670291 | 4 | 1.79E-09 | 3.42E-06 | PCNT | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.021 | .00112 | |

| chr22 | 45064135 | 45064392 | 4 | 3.11E-09 | 5.88E-06 | TTC38 | Exon;intron | 0 | −0.023 |

To address the potential confounding effect of differential PBMC cell content, we used a regression calibration based on peripheral blood leukocyte cell-specific methylation to estimate the specific monocyte cell type and granulocyte contamination for each sample.42 Significant differences (P =.004) were observed between asthmatic and nonasthmatic groups only for the concentration of NK cells (see Table E5 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Fifty-five of the 81 DMRs remained significant after adjustment for cell mixture (P < .05), and an additional 8 approached statistical significance (P < .1, see Table E6 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). As expected, the DMRs associated with NK cells (KIR2DL4, KIR2DL3, KIR3DL1, and KLRD1) were no longer significant after adjustment for differences in mononuclear cell populations, whereas RUNX3 (P = .04), IL13 (P = 2.8 × 10−5), and many other genes remained significant (see Table E6). Disease and biofunction enrichment analysis of the 55 DMRs identified organismal development, oversecretion of mucus and inflammatory/respiratory disease, and airway hyperresponsiveness among the most significantly enriched categories (P < .039, Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison corrected; see Table E7 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

To determine whether specific measures of allergy or asthma are associated with DNA methylation, among asthmatic patients, we investigated the relationship between methylation marks and either the total serum IgE concentration or percent predicted FEV1. Taking a genome-wide approach to DNA methylation and the serum concentration of IgE among asthmatic patients, we identified 11 IgE-associated DMRs (Fig 2, A, and see Table E8, A, in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), including a glutathione S-transferase (GSTT1). Focusing on the 81 asthma-associated DMRs (Fig 1, A), we found that 4 of these DMRs were associated with serum IgE concentrations (P < .05, Sidak corrected; Table II), and only one of those DMRs (TRMT12) overlapped with the 11 IgE-associated DMRs in the genome-wide analysis (Fig 2, A). We also investigated the relationship between DNA methylation and percent predicted FEV1 among asthmatic patients and found that 16 DMRs were identified in the genome-wide DNA analysis (Fig 2, B, and see Table E8, B), and 28 DMRs were associated with FEV1 when the analysis was limited to the 81 asthma-associated DMRs (Fig 1, A).

We next evaluated the relationship between asthma-, IgE-, or FEV1-associated DMRs and gene expression. Gene expression analysis identified several interesting genes associated with asthma (T-box transcription factor, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase, and NK cell genes) or the serum concentration of IgE among asthmatic patients (arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase) but not with percent predicted FEV1 (see Fig E3 and Table E9 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Correlation of methylation and expression revealed enrichment in expected relationships with hypomethylated genes associated with increased gene expression and hypermethylated genes associated with decreased gene expression (binomial P < .6 × 10−11 for enrichment in inverse relationships in asthma-related DMRs [Fig 3, A] and P < .01 for IgE-related DMRs [Fig 3, B]); however, a number of DNA methylation changes were not associated with canonical gene expression differences (Fig 3, A and B). This was not the case for FEV1 (see Fig E4 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

We also examined whether location of the DMR (upstream, gene body, or downstream of the gene) affected this relationship of methylation and expression. Most DMRs (85% [n = 69] for asthma and 82% [n = 9] for IgE) are in gene bodies, and only a few (4 for asthma and 1 for IgE) are upstream or downstream within 3 kb of the gene; therefore we were unable to detect any differences in methylation-expression relationships based on DMR location relative to gene. Of note, some DMRs are not associated with changes in expression (those close to zero on the y-axis in Fig 3, A and B, as well as a few intergenic DMRs that are >3 kb from any gene). However, among the DMRs within 3 kb of a gene, inverse correlations and gene expression are enriched in DMRs with higher statistical significance. We examined the percentage of inverse relationships in the 4 quartiles of DMRs ranked by adjusted (SLK-Sidak) P values and obtained the following results: 89% in the top quartile, 84% in the second quartile, 74% in the third quartile, and 55% in the bottom quartile. Additionally, the TH2 immunity genes IL13 and RUNX3 are also among the genes with inverse correlation of DNA methylation and gene expression. This analysis demonstrates that these inverse relationships rank at the top of asthma-associated DMRs and adds further biological relevance of our results. The finding that many of the inverse relationships are within gene bodies is in agreement with a recent publication that showed prominent hypomethylation of gene bodies with both inverse and direct correlation to gene expression in cancer50 and demonstrates that the relationship of gene body methylation and expression is more complex than previously thought.51

To further explore the relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression, we performed an integrative analysis of DNA methylation and expression using LCMix44 and identified 2484 methylation-expression pairs (posterior probability > 0.95 from the joint fit corresponding to a local false discovery rate <0.05), including RUNX3 and IL4, the expression of which was related to asthma-associated DNA methylation marks (Fig 3, C, and see Table E10 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Among the genes with the most significant methylation-expression relationship is an additional asthma-associated gene, ST2, the receptor for IL-33.52,53 Importantly, ST2 is one of the few genes that has consistently been associated with asthma in genome-wide association studies.54,55

We selected 10 loci from the 81 asthma-associated DMRs for internal and external validation by using pyrosequencing and an independent population of asthmatic children compared with our original control samples (Table I). Five loci were selected based on the relevance to asthma (IL13, RUNX3, CAT, PRF1, and TIGIT), 4 were selected based on large methylation differences between asthmatic patients and control subjects from the original comparison (ALPL, C2;ZBTB12, KLF6, and NBR2), and 1 locus (IL4) was selected based on the asthma-specific methylation-expression matrix. All 10 loci (13 CpG motifs) were validated internally in the original study population (P < .05, 1-tailed t test) comparing methylation changes detected by using the Illumina array and pyrosequencing assay (see Table E11 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). As expected based on previous comparison of Illumina and pyrosequencing data,56 there are some differences in percentage methylation change detected on the 2 platforms, but directionality and statistical significance are consistent. Five loci (RUNX3, IL4, CAT, KLF6, and NBR2, involving 8 CpG motifs) were validated externally in an independent population of children with asthma (P < .05, 1-tailed t test; see Table E11).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that methylation marks at specific loci are associated with asthma and define novel methylation-gene transcription relationships that might prove important in asthmatic patients. The relevance of epigenetic marks in asthmatic patients builds on our current understanding that the cause of asthma is associated with non-Mendelian inheritance, parent-of-origin patterns of inheritance, environmental exposures, and in utero exposures. Our findings that epigenetic marks in immune cells are associated with allergic asthma in inner-city children provide a provocative new direction for asthma research that is likely to have mechanistic, preventative, therapeutic, and public health implications and might establish novel biological insights into the development of asthma.

Our results suggest that epigenetic marks might prove important in understanding the pathogenesis of asthma. The asthma-associated DMRs appear to be biologically important; almost all were hypomethylated,57 the majority were within gene bodies or CpG islands,58 approximately 15% were in CpG island shores,59 and asthma-associated DMRs were associated with gene expression. Moreover, we found that 3 genes previously associated with TH2 immunity60 and asthma pathogenesis,61,62 IL4, IL13, and RUNX3, are hypomethylated in asthmatic patients. Although IL-4 and IL-13 are classic TH2 cytokines,60,61 RUNX3 is a transcription factor known to regulate CD4/CD8 T-lymphocyte development by interacting with T-box transcription factor and silencing IL-4 expression.63 Differential methylation of RUNX3 has previously been associated with lung cancer,64 as well as in utero exposure to cigarette smoke.65 Moreover, the previously unrecognized asthma-associated epigenetic marks and methylation-expression relationships that we observed might identify novel genes and networks that are critically involved in the complex pathogenesis of this disease. Methylation changes in KLF6 are of particular relevance given its role in activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase 1 during influenza A virus infection48 and TGF-β during respiratory syncytial virus infection49 and the importance of viral infections in childhood asthma.66

Our results add to a growing body of evidence that methylation marks direct the expression of genes that are critical to the development of TH2 immunity and allergic airway disease. In vitro development of mature TH2 cells has been associated with hypomethylation of CpG motifs in the promoters of IL4 and IL13 11,12,67 and the RAD50-hypersensitive site in the TH2 cytokine locus control region. Similarly, development of TH1 immunity is also influenced by methylation. For example, cord blood CD4+ cells enhance development of the TH1 lineage through progressive demethylation of the IFNG promoter.68 DNA methylation of promoter and enhancer elements of forkhead box protein 3 has been shown to influence the development of regulatory T cells.13 In vivo experimentally induced methylation changes in CD11c+ dendritic cells,69 CD19+ B lymphocytes,70 Ifng in CD4+ cells,71 and Runx3 in splenocytes and lung tissue10 have been observed in murine models of allergic airway disease. Demethylation with 5-aza-deoxycytidine demonstrates the importance of methylation marks in the development of TH2 immunity10 and allergic airway disease.71

Our results could potentially affect our approach to asthma prevention and treatment. Although mutations in epigenetic regulators and epigenetic signatures have been observed in hematologic malignancies and are being targeted therapeutically,72 interest in using pharmacologic modulation of epigenetic marks in patients with nonmalignant diseases is only beginning to emerge.73 Because epigenetic mechanisms are dynamic and reversible, it is entirely conceivable that a TH2-skewed phenotype could be reprogrammed therapeutically by altering the methylome with small-molecule inhibitors that target specific methylation sites in the genome.73 Moreover, the pharmacologic agents used to treat airway disease might function through epigenetic mechanisms; theophylline has been shown to affect histone deacetylase activity and improve steroid responsiveness.74

There are several limitations to our study. The main limitation is the use of PBMCs as “surrogate” tissue for clinically and biologically relevant changes that occur in the lung. Although nasal epithelial cells might better reflect changes in airway epithelia, as has recently been demonstrated for gene expression,75 PBMCs are the most reasonable surrogate for examination of methylation changes related to immune phenotypes in asthmatic patients and are the most accessible and least invasive to collect in children. Moreover, atopic asthma can be considered a systemic immunologic derangement with a dramatic manifestation in the pulmonary airways, further supporting the significance of our findings in PBMCs. Methylation changes we identified in PBMCs are small in magnitude but might be reflective of larger changes in the lung. Alternatively, they might be small due to the presence of multiple cell types in PBMCs; however, further studies will be needed to demonstrate this.

Second, although we were unable to evaluate the effect of exposures on the epigenome because of lack of exposure assessment in our study, this is an important future direction for the field.

The third limitation is reliance on a statistical deconvolution method to assess differences in cell composition in the absence of white blood count data.

The fourth limitation is the inability to detect differences in methyl- versus hydroxyl-methyl cytosine, which is believed to be a mark for demethylation,76 as well as changes in DNA methylation over time, because they are dynamic and influenced by exposures.

Finally, our association analysis is unable to distinguish between DNA methylation marks and gene expression being the cause or consequence of disease.

Despite these limitations, our findings that the epigenome is dysregulated in asthmatic patients provide a provocative new direction for this disease that might have important public health implications and might establish novel biological insights into the development of asthma. Although we identified strong associations between DNA methylation and gene expression, much more work will be needed to understand the complexities of this important regulatory mechanism in asthmatic patients.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

DNA methylation changes in genes with direct relevance to TH2 immunity and asthma are associated with allergic asthma in African American inner-city children.

DNA methylation changes are associated with changes in gene expression with enrichment in inversely correlated methylation-expression relationships.

Our results suggest that the epigenome is dysregulated in asthmatic patients, and this observation provides a provocative new direction for this disease that might have important mechanistic, therapeutic, and public health implications.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (N01-AI90052); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL101251); the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P01-ES18181); and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000075).

Abbreviations used

- DMR

Differentially methylated region

- NK

Natural killer

- PC

Principal component

- PCA

Principal components analysis

- PEER

Probabilistic estimation of expression residuals

- RUNX3

Runt-related transcription factor 3

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: I. V. Yang has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). A. Liu has received payment for lectures from Merck and is on the data safety monitoring committee from GlaxoSmithKline. G. T. O’Connor has received research support from the NIH. S. J. Teach has received research and travel support from the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute, Fight for Children, the DC Department of Health, and the Kellogg Foundation; is employed by Children’s National Health System; and receives royalties from Up-To-Date. M. Kattan has received research support from the NIH and is a member of the Novartis Advisory Board. R. Gruchalla has received research and travel support from the NIAID. S. J. Szefler has received research support from the NIAID and GlaxoSmithKline; has consultant arrangements with Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Genentech; has received payment for lectures from Merck; and has submitted a patent for β-adrenengic receptor polymorphism for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute CARE Network. M. A. Gill has received research support from the NIH/ NIAID. A. Calatroni has received research support from the NIH/NIAID. G. David has a contract with the NIH/NIAID. W. W. Busse has received research support from the NIH/NIAID and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; is a board member for Merck; has consultant arrangements with Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, Circassia, ICON, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Amgen, Med-Immune, NeoStem, Takeda, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has received royalties from Elsevier. D. A. Schwartz has received research support from the NIH and the Veterans Administration; has consultant arrangements with Novartis and Boehringer-Ingelheim; is employed by the University of Colorado Medical School and the Department of Veterans Affairs; has provided expert testimony from Weitz and Luxenberg Law Firm, Brayton and Purcell Law Firm, and Wallace and Graham Law Firm; has patents for TLR2 single nucleotide polymorphism, MUC5b single nucleotide polymorphism, and has patent applications (61/248,505, 61/666,233, 60/ 992,079); and has received royalties from Springer. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vercelli D. Discovering susceptibility genes for asthma and allergy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:169–182. doi: 10.1038/nri2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lockett GA, Holloway JW. Genome-wide association studies in asthma; perhaps, the end of the beginning. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:463–469. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328364ea5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss ST, Silverman EK. Pro: genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:631–633. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0485ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffatt MF, Cookson WO. The genetics of asthma. Maternal effects in atopic disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(suppl 1):56–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.0280s1056.x. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feinberg AP, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:143–153. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Epigenetic mechanisms and the development of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Digel W, Lubbert M. DNA methylation disturbances as novel therapeutic target in lung cancer: preclinical and clinical results. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, Gilliland FD. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:462–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0135OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Boon K, Garantziotis S, Li Z, Tomfohr J, et al. In utero supplementation with methyl donors enhances allergic airway disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3462–3469. doi: 10.1172/JCI34378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Lee GR, Kim ST, Spilianakis CG, Fields PE, Flavell RA. T helper cell differentiation: regulation by cis elements and epigenetics. Immunity. 2006;24:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santangelo S, Cousins DJ, Winkelmann NE, Staynov DZ. DNA methylation changes at human Th2 cytokine genes coincide with DNase I hypersensitive site formation during CD4(+) T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2002;169:1893–1903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1543–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez FD, Vercelli D. Asthma. Lancet. 2013;382:1360–1372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61536-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma S, Litonjua A. Asthma, allergy, and responses to methyl donor supplements and nutrients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1246–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales E, Bustamante M, Vilahur N, Escaramis G, Montfort M, de Cid R, et al. DNA hypomethylation at ALOX12 is associated with persistent wheezing in childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:937–943. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0870OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rastogi D, Suzuki M, Greally JM. Differential epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns in childhood obesity-associated asthma. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2164. doi: 10.1038/srep02164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breton CV, Byun HM, Wang X, Salam MT, Siegmund K, Gilliland FD. DNA methylation in the arginase-nitric oxide synthase pathway is associated with exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:191–197. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baccarelli A, Rusconi F, Bollati V, Catelan D, Accetta G, Hou L, et al. Nasal cell DNA methylation, inflammation, lung function and wheezing in children with asthma. Epigenomics. 2012;4:91–100. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busse WW, Mitchell H. Addressing issues of asthma in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(suppl):S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touleimat N, Tost J. Complete pipeline for Infinium((R)) Human Methylation 450K BeadChip data processing using subset quantile normalization for accurate DNA methylation estimation. Epigenomics. 2012;4:325–341. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, Simcha D, Langmead B, Johnson WE, et al. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrg2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser HB, Lam LL, Neumann SM, Kobor MS. Population-specificity of human DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-2-r8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stegle O, Parts L, Durbin R, Winn J. Bayesian framework to account for complex non-genetic factors in gene expression levels greatly increases power in eQTL studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolzhenko E, Smith AD. Using beta-binomial regression for high-precision differential methylation analysis in multifactor whole-genome bisulfite sequencing experiments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:215. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe AE, Murakami P, Lee H, Leek JT, Fallin MD, Feinberg AP, et al. Bump hunting to identify differentially methylated regions in epigenetic epidemiology studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:200–209. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzese DM, Scolyer RA, Huynh JL, Huang SK, Hirose H, Chong KK, et al. Epigenome-wide DNA methylation landscape of melanoma progression to brain metastasis reveals aberrations on homeobox D cluster associated with prognosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:226–238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcucci G, Yan P, Maharry K, Frankhouser D, Nicolet D, Metzeler KH, et al. Epigenetics meets genetics in acute myeloid leukemia: clinical impact of a novel sevengene score. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:548–556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.6337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Rabinovich E, Hennessy CE, Davidson EJ, Murphy E, et al. Relationship of DNA methylation and gene expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1263–1272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1452OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell JT, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Gaffney DJ, Pique-Regi R, Degner JF, et al. DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen BS, Schwartz DA, Yang IV, Kechris KJ. Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping, and correction of spatially correlated p-values. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2986–2988. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makismovic J, Gordon L, Oshlack ASWAN. Subset-quantile within array normalization for Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen KD, Aryee M. Analyze Illumina’s 450k methylation arrays. R package Version 120. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kechris KJ, Biehs B, Kornberg TB. Generalizing moving averages for tiling arrays using combined p-value statistics. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2010;9 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1434. Article29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence region for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62:626–633. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedersen BS, Yang IV, De S. CruzDB: software for annotation of genomic intervals with UCSC genome-browser database. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:3003–3006. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, et al. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dvorkin D, Biehs B, Kechris K. A graphical model method for integrating multiple sources of genome-scale data. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2013;12:469–487. doi: 10.1515/sagmb-2012-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biernacki C, Celeux G, Govaert G. Assessing a Mixture Model for Clustering with the Integrated Completed Likelihood. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2000;22:719–725. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, Wandler AM, Postlethwait JH, Guillemin K. Dynamic evolution of the LPS-detoxifying enzyme intestinal alkaline phosphatase in zebrafish and other vertebrates. Front Immunol. 2012;3:314. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mgbemena V, Segovia JA, Chang TH, Tsai SY, Cole GT, Hung CY, et al. Transactivation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene by Kruppel-like factor 6 regulates apoptosis during influenza A virus infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:606–615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mgbemena V, Segovia J, Chang T, Bose S. Kruppel-like factor 6 regulates transforming growth factor-beta gene expression during human respiratory syncytial virus infection. Virol J. 2011;8:409. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulis M, Heath S, Bibikova M, Queiros AC, Navarro A, Clot G, et al. Epigenomic analysis detects widespread gene-body DNA hypomethylation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1236–1242. doi: 10.1038/ng.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, Lee JH, LeProust EM, Park IH, et al. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akhabir L, Sandford A. Genetics of interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 in immune and inflammatory diseases. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:591–606. doi: 10.2174/138920210793360907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:103–110. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wjst M, Sargurupremraj M, Arnold M. Genome-wide association studies in asthma: what they really told us about pathogenesis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:112–118. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835c1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ober C, Yao TC. The genetics of asthma and allergic disease: a 21st century perspective. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:10–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roessler J, Ammerpohl O, Gutwein J, Hasemeier B, Anwar SL, Kreipe H, et al. Quantitative cross-validation and content analysis of the 450k DNA methylation array from Illumina, Inc. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:210. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu W, Baccarelli A, Carey VJ, Boutaoui N, Bacherman H, Klanderman B, et al. Variable DNA methylation is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:373–381. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1382OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho IC, Tai TS, Pai SY. GATA3 and the T-cell lineage: essential functions before and after T-helper-2-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, et al. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–2261. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fainaru O, Shseyov D, Hantisteanu S, Groner Y. Accelerated chemokine receptor 7-mediated dendritic cell migration in Runx3 knockout mice and the spontaneous development of asthma-like disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10598–10603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504787102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Djuretic IM, Levanon D, Negreanu V, Groner Y, Rao A, Ansel KM. Transcription factors T-bet and Runx3 cooperate to activate Ifng and silence Il4 in T helper type 1 cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:145–153. doi: 10.1038/ni1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stewart DJ. Wnt signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt356. djt356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maccani JZ, Koestler DC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Kelsey KT. Placental DNA methylation alterations associated with maternal tobacco smoking at the RUNX3 gene are also associated with gestational age. Epigenomics. 2013;5:619–630. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Szefler SJ, Chmiel JF, Fitzpatrick AM, Giacoia G, Green TP, Jackson DJ, et al. Asthma across the ages: knowledge gaps in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webster RB, Rodriguez Y, Klimecki WT, Vercelli D. The human IL-13 locus in neonatal CD4+ T cells is refractory to the acquisition of a repressive chromatin architecture. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:700–709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White GP, Hollams EM, Yerkovich ST, Bosco A, Holt BJ, Bassami MR, et al. CpG methylation patterns in the IFNgamma promoter in naive T cells: variations during Th1 and Th2 differentiation and between atopics and non-atopics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fedulov AV, Kobzik L. Allergy risk is mediated by dendritic cells with congenital epigenetic changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:285–292. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0400OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pascual M, Suzuki M, Isidoro-Garcia M, Padron J, Turner T, Lorente F, et al. Epigenetic changes in B lymphocytes associated with house dust mite allergic asthma. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1131–1137. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.9.16061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brand S, Teich R, Dicke T, Harb H, Yildirim AO, Tost J, et al. Epigenetic regulation in murine offspring as a novel mechanism for transmaternal asthma protection induced by microbes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.035. e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T, Huntly BJ. Targeting epigenetic readers in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:647–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arrowsmith CH, Bountra C, Fish PV, Lee K, Schapira M. Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:384–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cosio BG, Tsaprouni L, Ito K, Jazrawi E, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ. Theophylline restores histone deacetylase activity and steroid responses in COPD macrophages. J Exp Med. 2004;200:689–695. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Poole A, Urbanek C, Eng C, Schageman J, Jacobson S, O’Connor BP, et al. Dissecting childhood asthma with nasal transcriptomics distinguishes subphenotypes of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.025. e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Branco MR, Ficz G, Reik W. Uncovering the role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the epigenome. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:7–13. doi: 10.1038/nrg3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.