Abstract

Scavenger receptor A (SRA) has been implicated in the processes of tumor invasion and acts as an immunosuppressor during therapeutic cancer vaccination. Pharmacological inhibition of SRA function thus holds a great potential to improve treatment outcome of cancer therapy. Macromolecular natural product sennoside B was recently shown to block SRA function. Here we report the identification and characterization of a small molecule SRA inhibitor rhein. Rhein, a deconstructed analogue of sennoside B, reversed the suppressive activity of SRA in dendritic cell-primed T cell activation, indicated by transcription activation of il2 gene and production of IL-2. Rhein also inhibited SRA ligand polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) induced activation of transcriptional factors, including interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1). Additionally, this newly identified lead compound was docked into the homology models of the SRA cysteine rich domain to gain insights into its interaction with the receptor. It was then found that rhein can favorably interact with SRA cysteine rich domain. Collectively, rhein, being the first identified small molecule inhibitors for SRA, warrants further structure-activity relationship studies, which may lead to development of novel pharmacological intervention for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Scavenger receptor A, Natural product, Rhein, Cysteine-rich domain, Homology model, Cancer therapy

Graphical abstract

Scavenger receptor A (SRA) is a pattern recognition receptor (PRR), which is primarily expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs).1 It is involved in lipid metabolism, host defense, as well as cardiovascular diseases and Alzheimer’s disease.2–6 Recent studies revealed a novel feature of SRA in attenuating antigen-specific T cell activation and impeding therapeutically induced antitumor immune response.7–14 In agreement with this, SRA expression was preferentially upregulated in DCs from tumor-bearing mice as well as in human tumor-associated macrophages, and correlated positively with increasing pathological grades of malignancy, reduced survival, and/or poor treatment outcomes.15–18 It is thus conceivable that pharmacological inhibition of SRA function may provide therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment.

SRA can recognize a broad spectrum of ligands, including acetylated low density lipoprotein (Ac-LDL), polyribonucleotide I, polysaccharides fucoidan and dextran sulfate.19 Recently, two macromolecular natural products, namely sennoside B and tannic acid, were identified as SRA inhibitors, with sennoside B being a more specific ligand in dose-dependent binding to SRA.20 Sennoside B has a molecular weight of nearly 900, which undermines its potential for further development as a drug candidate. To address this issue, we employed a “deconstruction” approach and identified a new lead compound rhein. The biological activity of rhein as a small molecule inhibitor for SRA in rescuing T cell activation and its docking studies based on SRA cysteine rich domain homology models are described herein.

The “deconstruction-reconstruction-elaboration” strategy has been successfully used to study the structure-activity relationships of both synthetic compounds and natural products.21–24 Sennoside B has a symmetric structure (Fig. 1). To determine whether this dimeric form is necessary for its SRA recognition, we deconstructed it to the monomeric form and further to the metabolically more stable anthraquinone skeleton, i.e., rhein (Fig. 1). Indeed, rhein is also known as cassic acid, a natural product originally isolated from rhubarb.25

Figure 1. Lead identification with “Deconstruction” strategies.

Macromolecule sennoside B was first deconstructed to its monomeric form, then further to anthraquinone skeleton, i.e., rhein.

We first examined the effects of rhein and sennoside B on dendritic cell (DC)-stimulated T cell activation by measuring T cell-secreted interleukin (IL)-2 levels with an enzyme linked immunesorbant assay (ELISA). SRA-expressing, bone marrow-derived DCs (BM-DCs) were loaded with gp100(25-33) peptide, an antigen naturally expressed in human and mouse melanoma,10 and then co-cultured with gp100-specific naïve CD8+ T cells (as responders) in the presence of sennoside B or rhein (20 µM). It was shown that both rhein and sennoside B significantly enhanced T cell activation compared to the vehicle control, and that rhein induced higher production of IL-2 than did sennoside B (Fig. 2A), suggesting that these two agents, rhein in particular, are able to reverse the immunosuppressive activity of SRA.

Figure 2. Rhein reverses suppressive activity of SRA in DC-primed T cell activation.

(A) WT bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs), pulsed with 1 µg/mL of gp100(25-33) peptide, were used to stimulate gp100-specific CD8+ T cells at a ratio of 1:10 in the presence of rhein or sennoside B (20 µM) for 56 hours. The IL-2 levels in the supernatants were assessed using ELISA. (B) WT and SRA−/− BM-DCs, loaded with 0.1 µg/mL OVA257-264 peptide, were co-cultured with OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the presence of rhein at indicated concentrations for 56 hours. The supernatants were analyzed for IL-2 levels using ELISA. The values are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to control.

We further tested the inhibitory effect of rhein on SRA activity using a T cell activation assay involving a different antigen. Wild type (WT) BM-DCs, pulsed with ovalbumin (OVA)257-264 peptide, were used to stimulate OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the presence of different concentrations of rhein. The correspondingly treated SRA−/− BM-DCs served as controls. While a modest increase in the levels of IL-2 was shown in WT BM-DC-T cell co-culture after treatment with 10 µM rhein, significantly enhanced IL-2 production was observed by treatment with 30 µM rhein (Fig. 2B). However, rhein didn’t alter IL-2 secretion from T cells stimulated by SRA−/− BM-DCs (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that rhein-enhanced T cell activation is due to its inhibition of SRA-associated immunosuppressive activity.

We also developed β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) assays using B3Z cells to evaluate SRA inhibitors on T cell activation, which was achieved by treatment with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies as previously described.26 B3Z cell line is an OVA-specific CD8+ T cell hybridoma, which carries a lacZ construct driven by NF-AT elements from the promoter of il2 gene.27 β-Gal is encoded by the lacZ gene of the lac operon in Escherichia coli. Therefore, activation of B3Z T cells triggers the transcriptional activation of il2 gene and production of lacZ, which can be visualized by using chromogenic substrates. As expected, anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies induced T cell activation as indicated by a marked increase of β-Gal (Fig. 3). Presence of SRA impaired T cell activation induced by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, which is consistent with our previous report of direct T-cell inhibitory activity of SRA.28 Treatment with rhein significantly reversed the T-cell suppressive activity of SRA in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Rhein restores SRA-impaired transcription of il2 gene during T cell activation.

B3Z cells were seeded at density of 2×106 cells/well in a plate pre-coated with anti-CD3 antibodies and stimulated with anti-CD28 antibodies for 5 hours in the presence of 10 µg/mL SRA protein plus rhein with indicated concentrations. Cells without treatment served as negative controls. A colorimetric assay was used to detect β-Gal activity in activated B3Z cells. The values are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * indicates p < 0.05, *** indicates p < 0.001 compared to anti-CD3/CD28 plus SRA treatment.

DCs sense pathogens or ‘dangers’ through different classes of highly conserved PRRs such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) and scavenger receptors. Activation of innate PPRs triggers multiple intracellular signaling cascades and expression of a variety of genes involved in the inflammatory and immune responses. Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)], a synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), can engage TLR3 directly and activate the interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-dependent pathway, resulting in production of Interferon (IFN)-β.29–31 Secreted IFN-β can act in an autocrine or a paracrine fashion, leading to activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1).32, 33 Given that SRA was recently suggested to mediate the cellular entry of extracellular dsRNA and subsequent delivery to its receptor,34, 35 we examined the effect of rhein on poly(I:C) induced activation of IRF3 and STAT1 in murine DC1.2 cells. Western Blotting analysis showed that poly(I:C) stimulation resulted in phosphorylation of IRF3 and STAT1 (Fig. 4, lane 2), which was consistent with our previously published data.36 Treatment with rhein decreased the activation of IRF3 and STAT1 dose-dependently (Fig. 4, lanes 6–8).

Figure 4. Rhein decreases poly(I:C)-induced activation of IRF3 and STAT1.

DC1.2 cells were pretreated with rhein at indicated concentrations for 2 hours, followed by stimulation with poly(I:C) in the presence or absence of rhein for 3 hours. The total protein were extracted and subjected to immunoblotting analysis to assess the phosphorylation of IRF3 or STAT1.

As a prototype member in class A scavenger receptors, SRA is composed of six structural domains: N-terminal cytoplasmic, transmembrane, spacer, α helical coiled coil, collagenous and cysteine rich. While the collagenous domain has been implicated in ligand binding,19, 37 recent work by Tsay and colleagues showed that the cysteine rich domain of SRA may also serve as a potential binding site for Ac-LDL.38 To gain insights into the interaction between rhein and SRA at molecular level, as well as to guide future molecular design of rhein derivatives as SRA inhibitors, SRA cysteine rich domain homology models were built based on the available crystal structures of the cysteine rich domain of MARCO in its monomer and dimer form (PDB: 2OY3 and 2OYA),39 another member of the same class A scavenger receptors. Of note, dimeric structure of the MARCO cysteine rich domain is proposed to be a β-strand-swapped form of two monomers. The putative binding sites for rhein were then identified through exhaustive ligand docking on the built homology models using GOLD5.240 followed by HINT41 scoring.

Based on the hydrophobic and electrostatic properties of the protein surface five unique binding sites were identified on the monomer model while in the dimer model four more binding sites focusing on the interface of the two monomers were observed. The obtained HINT scores were summarized in Table 1. In practice the best HINT score from the docking process could be an outlier docking-pose-wise whereas averaging HINT scores may provide equal weightage to each docked solution despite that most of the solutions are likely to be sub-optimal. In contrast, Boltzmann distribution weights the data with reference to the best score and thus provides more weightage to the optimal solutions. Very encouragingly, site 2 from the monomer model displayed the highest HINT scores in all three scoring categories. So did site 3 from the dimer model. Thus these two solutions might be two plausible binding sites for rhein to interact with the SRA cysteine rich domain.

Table 1.

HINT scores of the putative binding sites for rhein in monomer and dimer homology models of the SRA cysteine rich domain

| Model | Putative Binding Sites |

HINT Scores |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Boltzmann average | ||

| Monomer | 1 | 1657 | −170 | 1147 |

| 2 | 2228 | 1088 | 1801 | |

| 3 | 1725 | 498 | 1349 | |

| 4 | 1381 | 188 | 924 | |

| 5 | 1669 | 468 | 1100 | |

| Dimer | 1 | 1020 | −156 | 507 |

| 2 | 1413 | 277 | 1009 | |

| 3 | 2281 | 659 | 1838 | |

| 4 | 1241 | −116 | 836 | |

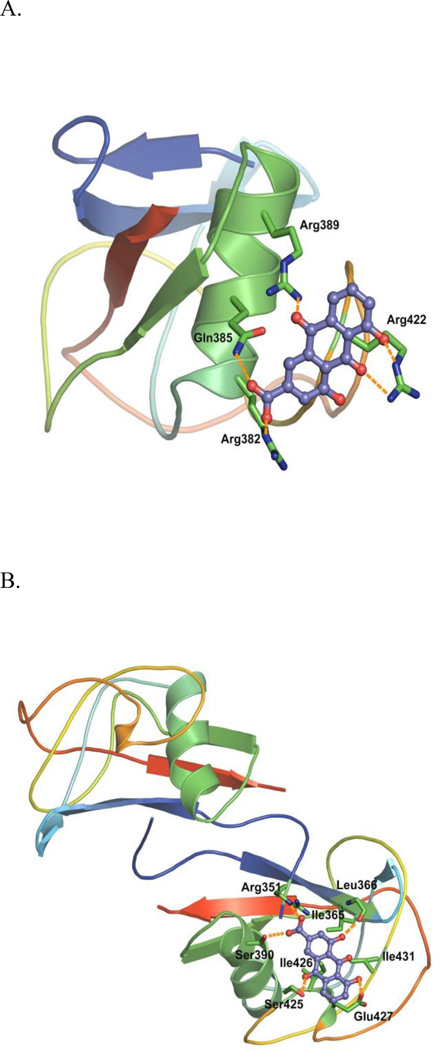

Figure 5 illustrates the best Boltzmann average HINT scored-docking poses on each of the two binding sites. In the monomer model, a cluster of the basic residues (Arg382, 389, and 422) together with Gln385 provided the primary impetus for rhein binding (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in the dimer model, Ile365, 426 and 431 of one subunit formed a hydrophobic cavity to interact with the anthraquinone backbone of rhein. In addition, Arg351 (from the other subunit, hence the interface), Ser390, and Ser425 side chains acted as hydrogen bond donor while Leu366 backbone carbonyl and Glu427 side chain served as hydrogen bond acceptor (Fig. 5B). Intriguingly, 4-hydroxy group and 10-oxo of rhein did not appear to participate in binding in the monomer and dimer models as significantly as we expected. Nonetheless, rhein may bind to SRA cysteine rich domain monomer as well as dimer. Further direct binding assays and site directed mutagenesis experiments will help validate these models for SRA-rhein interaction. It was reported that SRA also exists in a form of trimer for its biological function.42 The information obtained may help define the putative binding mode of rhein with such a trimeric form once a reliable template to construct such a trimer is available.

Figure 5. Rhein binding poses with the highest Boltzmann average HINT scores in the SRA cysteine rich domain homology models.

Protein structures are shown in cartoon. Residues involved in interactions are shown in sticks. Rhein is shown in purple. Potential hydrogen bonding interactions are shown in orange dashes. (A) Monomer Model. (B) Dimer Model. For representation purpose, only one molecule of rhein was shown in one subunit of the SRA cysteine rich domain dimer model.

In conclusion, we have identified a new lead compound rhein as a potential SRA inhibitor via “deconstruction” strategy. Rhein was pharmacologically characterized to be able to enhance T cell activation in multiple immunological assays, indicated by increased production of IL-2 and transcriptional activation of il2 gene. Additionally, the SRA inhibitory activity of rhein was shown in poly(I:C) triggered inflammatory signaling in DCs. Our molecular modeling studies suggested that rhein may bind to the cysteine rich domain in SRA monomer as well as the dimer. These results provide a basis for further development of small molecular inhibitors for SRA to achieve potential therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center Pilot Project Grant and by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant CA175033.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://

References

- 1.Platt N, Haworth R, Darley L, Gordon S. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;212:1. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)12002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunne DW, Resnick D, Greenberg J, Krieger M, Joiner KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haworth R, Platt N, Keshav S, Hughes D, Darley E, Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Kodama T, Gordon S. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson AM. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:20. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, Takashima Y, Kawabe Y, Cynshi O, Wada Y, Honda M, Kurihara H, Aburatani H, Doi T, Matsumoto A, Azuma S, Noda T, Toyoda Y, Itakura H, Yazaki Y, Steinbrecher UP, Ishinash S, Maeda N, Gordon S, Kodama T. Nature. 1997;386:292. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C-N, Shiao Y-J, Shie F-S, Guo B-S, Chen P-H, Cho C-Y, Chen Y-J, Huang F-L, Tsay H-J. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:221. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo C, Yi H, Yu X, Hu F, Zuo D, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:101. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C, Yi H, Yu X, Zuo D, Qian J, Yang G, Foster BA, Subjeck JR, Sun X, Mikkelsen RB, Fisher PB, Wang X-Y. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2331. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian J, Yi H, Guo C, Yu X, Zuo D, Chen X, Kane JM, Repasky EA, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. J Immunol. 2011;187:2905. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X-Y, Facciponte J, Chen X, Subjeck JR, Repasky EA. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4996. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi H, Guo C, Yu X, Gao P, Qian J, Zuo D, Manjili MH, Fisher PB, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6611. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi H, Yu X, Gao P, Wang Y, Baek SH, Chen X, Kim HL, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. Blood. 2009;113:5819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi H, Zuo D, Yu X, Hu F, Manjili MH, Chen Z, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. J Mol Med. 2012;90:413. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0828-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu X, Yi H, Guo C, Zuo D, Wang Y, Kim HL, Subjeck JR, Wang X-Y. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herber DL, Cao W, Nefedova Y, Novitskiy SV, Nagaraj S, Tyurin VA, Corzo A, Cho HI, Celis E, Lennox B, Knight SC, Padhya T, McCaffrey TV, McCaffrey JC, Antonia S, Fishman M, Ferris RL, Kagan VE, Gabrilovich DI. Nat Med. 2010;16:880. doi: 10.1038/nm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamura K, Komohara Y, Takaishi K, Katabuchi H, Takeya M. Pathol Int. 2009;59:300. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Noma H, Kubo F, Sakoda M, Ueno S, Natsugoe S, Takao S. J Surg Res. 2011;167:e211. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohtaki Y, Ishii G, Nagai K, Ashimine S, Kuwata T, Hishida T, Nishimura M, Yoshida J, Takeyoshi I, Ochiai A. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1507. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181eba692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger M, Herz J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raycroft MT, Harvey BP, Bruck MJ, Mamula MJ. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erlanson DA, McDowell RS, O’Brien Y. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3463. doi: 10.1021/jm040031v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh S, Elder A, Guo J, Mani U, Patane M, Carson K, Ye Q, Bennett R, Chi S, Jenkins T, Guan B, Kolbeck R, Smith S, Zhang C, LaRosa G, Jaffee B, Yang H, Eddy P, Lu C, Uttamsingh V, Horlick R, Harriman G, Flynn D. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2669. doi: 10.1021/jm050965z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glennon RA. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:927. doi: 10.2174/138955705774329519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker KA, Wang P. Org Lett. 2007;9:4793. doi: 10.1021/ol702144u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hesse O. Pharm J. 1895;1:325. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-Valdepeñas C, Martín AG, Ramakrishnan P, Wallach D, Fresno M. J Immunol. 2006;176:4666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karttunen J, Sanderson S, Shastri N. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo D, Yu X, Guo C, Wang H, Qian J, Yi H, Lu X, Lv ZP, Subjeck JR, Zhou H, Sanyal AJ, Chen Z, Wang X-Y. Hepatology. 2013;228 doi: 10.1002/hep.25983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choe J, Kelker MS, Wilson IA. Science. 2005;309:581. doi: 10.1126/science.1115253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Immunity. 2006;25:349. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Z, Mak TW, Sen G, Li X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308496101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marie I, Durbin JE, Levy DE. EMBO. J. 1998;17:6660. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato M, Hata N, Asagiri M, Nakaya T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tirapu I, Giquel B, Alexopoulou L, Uematsu S, Flavell R, Akira S, Diebold SS. Int Immunol. 2009;21:871. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeWitte-Orr SJ, Collins SE, Bauer CM, Bowdish DM, Mossman KL. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000829. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu F, Yu X, Wang H, Zuo D, Guo C, Yi H, Tirosh B, Subjeck JR, Qiu X, Wang X-Y. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1086. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowdish DM, Gordon S. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang F-L, Shiao Y-J, Hou S-J, Yang C-N, Chen Y-J, Lin C-H, Shie F-S, Tsay H-J. J Biomed Sci. 2013;20:54. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-20-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ojala JR, Pikkarainen T, Tuuttila A, Sandalova T, Tryggvason K. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:727. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kellogg GE, Abraham DJ. Eur J Med Chem. 2000;35:651. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kodama T, Reddy P, Kishimoto C, Krieger M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.