Abstract

Objective:

Research on moderate drinking has focused on the average level of drinking. Recently, however, investigators have begun to consider the role of the pattern of drinking, particularly heavy episodic drinking, in mortality. The present study examined the combined roles of average drinking level (moderate vs. high) and drinking pattern (regular vs. heavy episodic) in 20-year total mortality among late-life drinkers.

Method:

The sample comprised 1,121 adults ages 55–65 years. Alcohol consumption was assessed at baseline, and total mortality was indexed across 20 years. We used multiple logistic regression analyses controlling for a broad set of sociodemographic, behavioral, and health status covariates.

Results:

Among individuals whose high level of drinking placed them at risk, a heavy episodic drinking pattern did not increase mortality odds compared with a regular drinking pattern. Conversely, among individuals who engage in a moderate level of drinking, prior findings showed that a heavy episodic drinking pattern did increase mortality risk compared with a regular drinking pattern. Correspondingly, a high compared with a moderate drinking level increased mortality risk among individuals maintaining a regular drinking pattern, but not among individuals engaging in a heavy episodic drinking pattern, whose pattern of consumption had already placed them at risk.

Conclusions:

Findings highlight that low-risk drinking requires that older adults drink low to moderate average levels of alcohol and avoid heavy episodic drinking. Heavy episodic drinking is frequent among late-middle-aged and older adults and needs to be addressed along with average consumption in understanding the health risks of late-life drinkers.

Excessive alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for chronic disease and injury (Rehm et al., 2009), but moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with reduced total mortality (Di Castelnuovo et al., 2006). However, research on moderate drinking has focused on the average level of drinking, masking diverse underlying patterns of drinking (Naimi et al., 2013). Among individuals whose average consumption is moderate, drinking may vary from a regular pattern to occasions of heavy episodic drinking. Recently, investigators have begun to consider the role of drinking pattern in mortality (Roerecke et al., 2011; Wannamethee, 2013).

Heavy episodic drinking and mortality

Heavy episodic drinking is linked to approximately half of alcohol-related mortality (Naimi et al., 2014; Stahre et al., 2014). Among Finnish men, those who consumed six or more drinks per drinking occasion showed increased total mortality compared to those without such a pattern, independent of overall alcohol consumption (Kauhanen et al., 1997; Laatikainen et al., 2003). Further, among Norwegians ages 20–62 years, drinking five drinks or more per occasion, even when infrequent, was linked to increased 20-year total mortality (Graff-Iversen et al., 2013). Similarly, among U.S. adults 17 years of age and older followed for 9 years, drinking five or more drinks a day at any frequency predicted increased total mortality risk (Plunk et al., 2014).

Combined effects of drinking level and drinking pattern

Most research on the combined effects of level and pattern of drinking on mortality has examined moderate drinkers. Among light- to moderate-drinking (up to an average of two drinks/day) U.S. adults 18 years of age and older followed for 11 years, heavy drinking occasions (eight drinks/occasion or getting drunk monthly) were linked to higher total mortality risk (Rehm et al., 2001). Moreover, among late-middle-aged patients tracked after myocardial infarction, the total mortality advantage associated with light drinking (up to one drink/day) was eliminated by heavy drinking occasions (three or more drinks/occasion) (Mukamal et al., 2005). Similarly, among U.S. adults 18 years of age and older, low average alcohol consumption (one to two drinks/day for men, one drink/day for women) failed to show reduced heart disease mortality across 15 years among individuals reporting heavy drinking occasions (five or more drinks/occasion) (Roerecke et al., 2011).

Schoenborn et al. (2014) looked at the link of both level and pattern of drinking with mortality among adults 18 years of age and older followed for 10 years. They found that heavy episodic drinking increased the risk of dying from liver disease for average light to moderate drinkers (up to 7 drinks/week for women and 14 drinks/week for men). However, heavy episodic drinking was unrelated to liver mortality risk for heavier drinkers (>7 drinks/week for women and >14 drinks/week for men) whose average consumption already had placed them at risk.

Present study

Consistent with previous studies (Mukamal et al., 2005; Rehm et al., 2001; Roerecke et al., 2011), in research with the present sample we found that, among older moderate drinkers, those who engage in heavy episodic drinking showed increased total mortality risk compared with regular moderate drinkers (Holahan et al., 2014). Building on previous research by Schoenborn et al. (2014), the purpose of the present study was to extend our prior work to systematically examine the combined roles of drinking level and drinking pattern in 20-year total mortality. We examined this question among 1,121 older adults ages 55–65 years at baseline. Alcohol consumption was assessed at baseline, and total mortality was indexed across 20 years. We applied National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007) definitions of moderate and heavy episodic drinking.

We posed three hypotheses that, consistent with NIAAA guidelines, reflect the assumption that high-risk drinking involves either high average consumption or episodic heavy drinking. First, we focused on the effects of pattern of drinking. In contrast to our earlier findings among average moderate drinkers (Holahan et al., 2014) and consistent with Schoenborn et al. (2014), we anticipated that pattern of drinking would not be significantly related to mortality when level of drinking is high. Next, extending this rationale, we focused on the effects of level of drinking. We predicted that level of drinking would be significantly related to mortality odds when pattern of drinking is regular. In contrast, we predicted that level of drinking would not be significantly related to mortality when pattern of drinking is heavy episodic.

Method

Sample selection and characteristics

The present study is part of an overall project that has examined late-life patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems (Brennan et al., 2010, 2011; Moos et al., 2004, 2009, 2010; Schutte et al., 2006) among late-middle-aged and older adults. The sample at baseline included individuals between the ages of 55 and 65 years who had had outpatient contact with one of two large medical centers in the previous 3 years. The sample is comparable to similarly aged community samples with respect to health characteristics such as prevalence of chronic illness and hospitalization (Brennan & Moos, 1990; Moos et al., 1991). Of eligible respondents contacted at baseline, 92% agreed to participate, and 89% (1,884) of these individuals provided complete data at baseline. The study was approved by the Stanford University Medical School Panel on Human Subjects; after the project was fully explained, participants provided signed informed consent. The present study focused on 1,121 participants from the overall project who consumed alcohol during the past year. This sample included 402 (36%) women and 719 (64%) men. At baseline, participants were an average of 61 (SD = 3.12) years of age, predominantly White (92%), and 74% were married.

Measures

Descriptive and psychometric information on the measures is available in the following sources: (a) Health and Daily Living Form (Moos et al., 1992) for the measures of alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, smoking status, and physical activity; (b) Life Stressors and Social Resources Inventory (Moos & Moos, 1994) for the measures of medical conditions, number of close friends, and quality of friend support; and (c) Coping Responses Inventory (Moos, 1993) for the measure of avoidance coping.

Alcohol consumption groups

Level of drinking.

The average level of drinking was assessed at baseline with a quantity-frequency index. Respondents were asked, “During the last month, how much of each of the following beverages did you usually drink in a typical day when you drank that beverage?” The quantity of alcohol consumption was assessed by items that measured amounts of wine, beer, and distilled spirits participants had consumed on the days they drank in the last month. Responses to these items were converted to reflect the ethanol content of the beverages consumed. The frequency of alcohol consumption was assessed by responses to questions asking how often per week (never, less than once, once or twice, three to four times, nearly every day) participants had consumed wine, beer, or distilled spirits in the last month. From this information, quantity-frequency values were calculated to provide indices of participants’ average daily ethanol consumption from each beverage type. Summing average daily ethanol consumption from the three beverage types provided a composite index of participants’ average daily level of drinking.

Using the measure of average daily level of drinking, the number of drinks per day was indexed based on the approximation that, in the United States, 5 oz. of wine, 12 oz. of beer, and 1 shot (1.5 oz.) of distilled spirits contain an average of 0.6 oz. of ethanol (NIAAA, 2007). Applying NIAAA guidelines (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007), moderate drinkers were identified as individuals whose average daily level of drinking at baseline was at least one half drink per day but no more than one drink/day for women and two drinks/day for men. Correspondingly, high drinkers were identified as individuals whose average daily level of drinking at baseline was greater than one drink per day for women and two drinks/day for men. Following Holahan et al. (2014), very light drinkers (>0 to <0.5 drink on average per day) were excluded because it was statistically unlikely that they would be heavy episodic drinkers.

Pattern of drinking.

Next, we identified the pattern of drinking through responses to additional items at baseline that asked separately for wine, beer, and distilled spirits: “During the last month what was the largest amount you drank of each of the following beverages?” Response options were indexed in number of glasses of wine, cans of beer, and shots of distilled spirits. Heavy episodic heavy drinking was defined consistent with NIAAA guidelines (Gunzerath et al., 2004) and in a manner identical to that used in the U.S. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions and the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Chavez et al., 2011). Regular drinking was defined as consuming fewer than four (for women) and fewer than five (for men) drinks on the occasion of the largest amount of drinking. Correspondingly, heavy episodic drinking was defined as consuming four or more (for women) and five or more (for men) drinks on the occasion of the largest amount of drinking. Additional items asked, “How often did you drink these larger amounts of wine, beer, or hard liquor during the last month?” Responses were categorized to index frequencies of less than once a week versus once a week or more.

Sociodemographic factors.

In addition to age and gender (female = 0, male = 1), two sociodemographic factors were assessed at baseline: socioeconomic status and marital status. We indexed socioeconomic status as the average of participants’ family income and years of education, using standard scores for both measures to equate their scales. Marital status was assessed by a dichotomous index (not married = 0, married = 1).

Medical conditions.

Medical conditions at baseline were indexed as a count of nine self-reported medical conditions experienced in the past 12 months (cancer, diabetes, heart problems, stroke, high blood pressure, anemia, bronchitis, kidney problems, and ulcers). Participants were instructed to report a medical condition “only if diagnosed by a physician.”

Obesity.

Body mass index (BMI) was based on reported height and weight at baseline. BMI was calculated as (weight in pounds × 703) / height in inches squared. Obesity was operationalized as a BMI of 30 or more (score = 1) versus a BMI of less than 30 (score = 0).

Smoking status.

Current cigarette smoking at baseline was operationalized as smoking one or more cigarettes per day (nonsmoker = 0, smoker = 1).

Physical activity.

Following previous research (Harris et al., 2006; Holahan et al., 2014), we derived a partial index of the level of physical activity at baseline by summing four items asking participants whether (no = 0, yes = 1) during the last month they engaged in (a) swimming or tennis with friends, (b) swimming or tennis with family, (c) long hikes or walks with friends, and (d) long hikes or walks with family.

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms at baseline were evaluated by responses to questions about 18 symptoms experienced during the previous month. Seven items evaluated mood-related symptoms (e.g., feeling depressed [sad or blue]), and 11 items were related to behavioral manifestations of depression (e.g., loss of interest or pleasure in your usual activities). Responses were reported on a 5-point scale reflecting how frequently symptoms were experienced, from never (0) to often (4). The depressive symptoms score is the sum of responses across the 18 items (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Avoidance coping.

Respondents were asked at baseline to identify the “most important problem” they had experienced in the past 12 months and to rate how frequently they had engaged in a variety of coping responses to deal with it, using a 4-point scale ranging from not at all (0) to fairly often (3). Avoidance coping included six items evaluating cognitive attempts to avoid thinking about the problem (e.g., “Did you try to deny how serious the problem really was?”) and six items related to behavioral attempts to reduce tension rather than dealing directly with the problem (e.g., “Did you take it out on other people when you felt angry or depressed?”). The avoidance coping score is the sum of responses across the 12 items (Cronbach’s α = .74).

Number of close friends.

Number of close friends was indexed at baseline based on response to an item that asked, “How many close friends do you have, people you feel at ease with and can talk to about personal matters?” Responses were coded from 0 to 4 or more.

Quality of friend support.

Quality of friend support was indexed at baseline as the sum of six items. For example, respondents were asked, “Can you count on your friends to help you when you need it?” Responses were scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from never (0) to often (4) (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Total mortality.

The outcome was total mortality (survival = 0, death = 1) during the 20-year follow-up. Death was confirmed by a death certificate in 92% of cases, by another official source (primarily the Social Security Death Index) for 7% of cases, and verbally by telephone by an individual at the participant’s former residence (primarily the spouse) for 1% of cases.

Analytic plan.

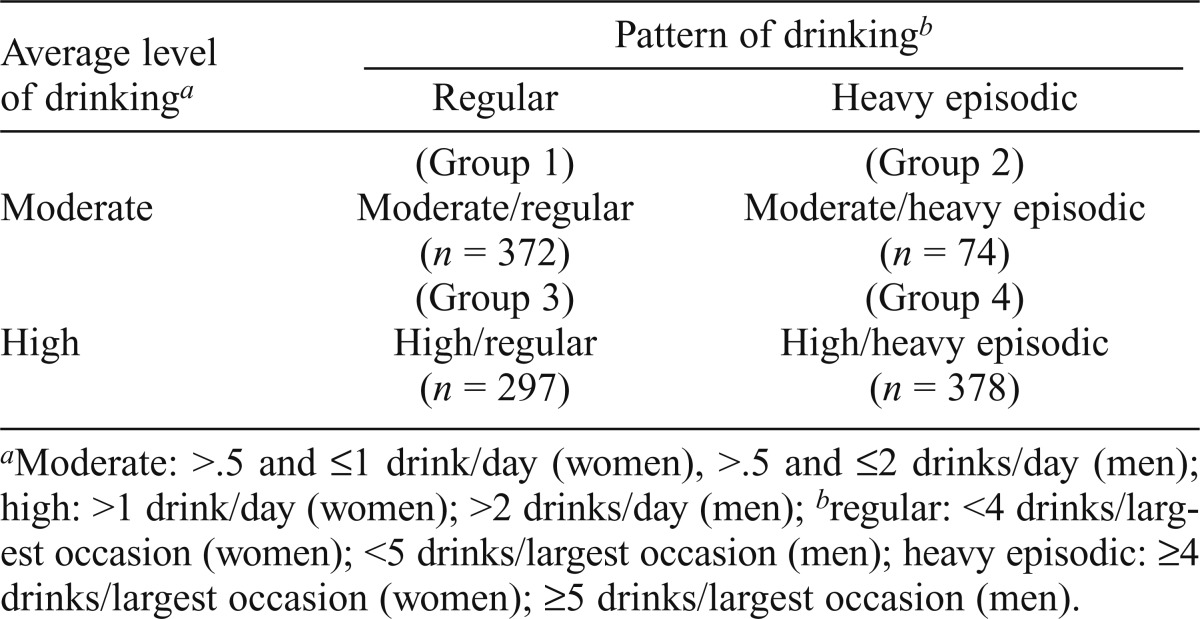

We defined four alcohol consumption groups at baseline by crossing the average level of drinking with the pattern of drinking (Table 1). We conducted three planned comparisons using multiple logistic regression analyses to examine the roles of drinking level and drinking pattern in 20-year mortality. The planned comparisons examined (a) the pattern of drinking when the level of drinking is high, (b) the level of drinking when the pattern of drinking is regular, and (c) the level of drinking when the pattern of drinking is heavy episodic. Following Holahan et al. (2010, 2014), the multiple logistic regression analyses controlled for age, gender, socioeconomic status, marital status, medical conditions, obesity, smoking status, physical activity, depressive symptoms, avoidance coping, number of close friends, and quality of friend support.

Table 1.

Alcohol consumption groups

| Average level of drinkinga | Pattern of drinkingb |

|

| Regular | Heavy episodic | |

| Moderate | (Group 1) | (Group 2) |

| Moderate/regular | Moderate/heavy episodic | |

| (n = 372) | (n = 74) | |

| High | (Group 3) | (Group 4) |

| High/regular | High/heavy episodic | |

| (n = 297) | (n = 378) | |

Moderate: >.5 and ≤1 drink/day (women), >.5 and ≤2 drinks/day (men); high: >1 drink/day (women); >2 drinks/day (men);

regular: <4 drinks/largest occasion (women); <5 drinks/largest occasion (men); heavy episodic: ≥4 drinks/largest occasion (women); ≥5 drinks/largest occasion (men).

Results

Background information

A total of 514 (46%) of the 1,121 participants died during the 20-year follow-up. Observed mortality rates for the four baseline alcohol consumption groups were as follows: moderate-regular = 37% (137 of 372), moderate-heavy episodic = 61% (45 of 74), high-regular = 42% (125 of 297), and high-heavy episodic = 55% (207 of 378).

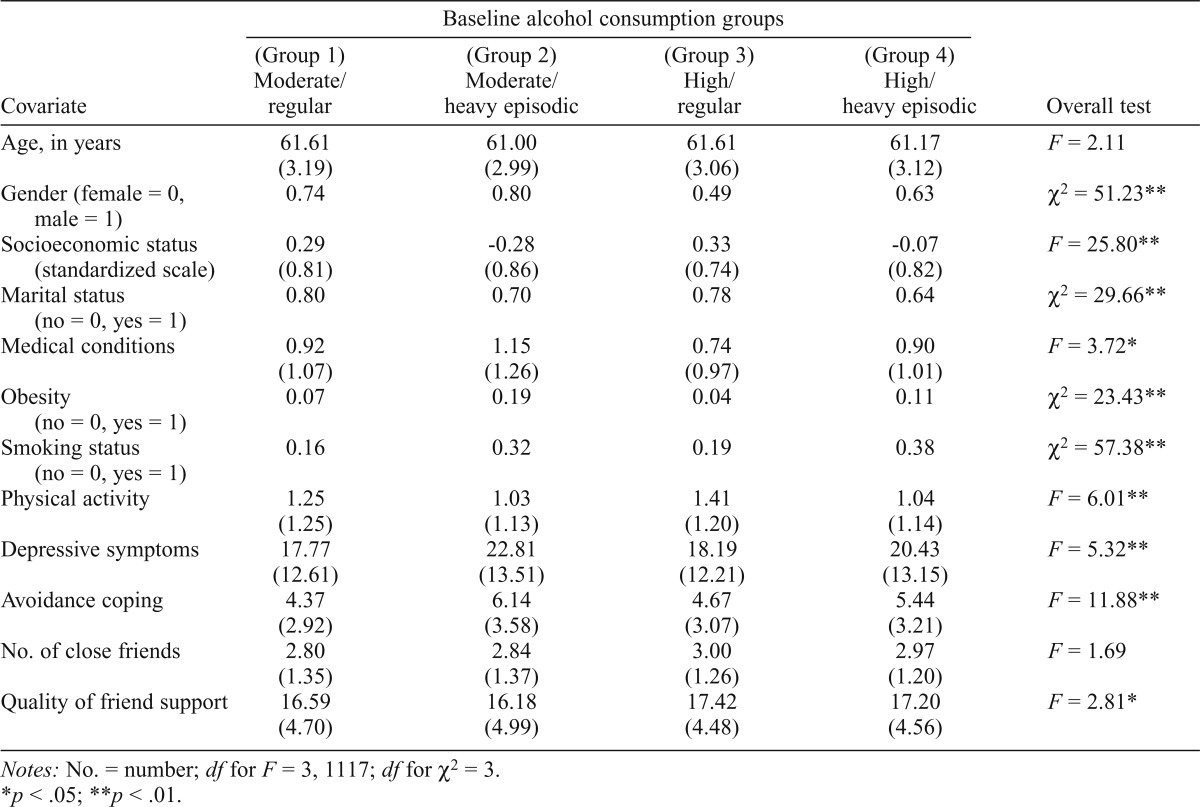

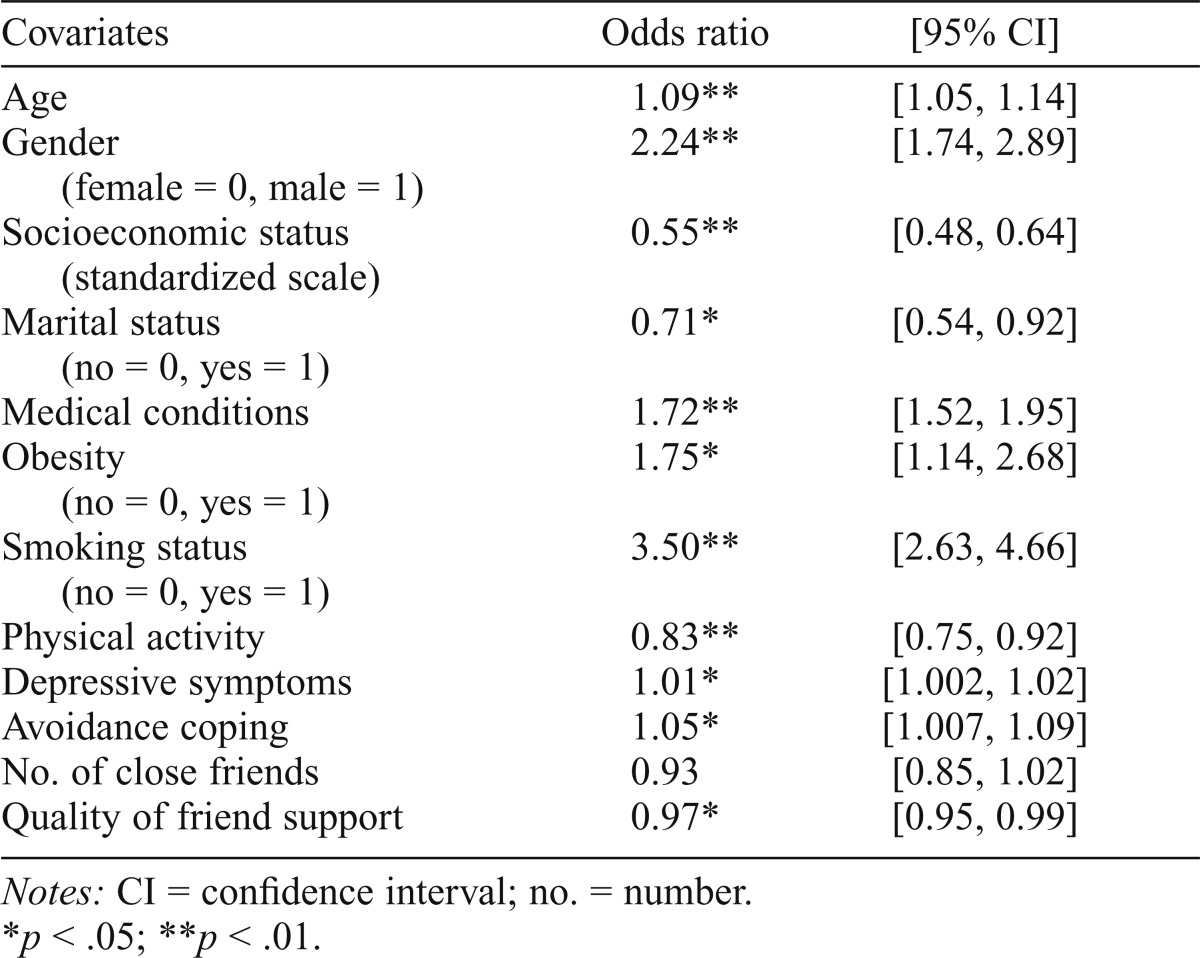

In preliminary analyses, we examined the association between alcohol group membership and each covariate using analyses of variance and chi-square analyses (Table 2). We also examined the association between each covariate and 20-year mortality using logistic regression analyses (Table 3). In addition, we examined whether heavy episodic drinking frequency (<once a week vs. ≥once a week) was associated with mortality among heavy episodic drinkers. Heavy episodic drinking frequency was not significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 1.31, p = .26, 95% CI [0.82, 2.08]). The interaction of level of drinking with heavy episodic drinking frequency in predicting mortality was not significant (OR = 0.59, p = .45, 95% CI [0.15, 2.31]).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) for baseline covariates by baseline alcohol consumption group membership. For continuous variables, standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Results of overall F and chi-square tests are shown in the last column (N = 1,121).

| Covariate | Baseline alcohol consumption groups |

Overall test | |||

| (Group 1) Moderate/regular | (Group 2) Moderate/heavy episodic | (Group 3) High/regular | (Group 4) High/heavy episodic | ||

| Age, in years | 61.61 (3.19) | 61.00 (2.99) | 61.61 (3.06) | 61.17 (3.12) | F = 2.11 |

| Gender (female = 0, male = 1) | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 0.63 | χ2 = 51.23** |

| Socioeconomic status (standardized scale) | 0.29 (0.81) | -0.28 (0.86) | 0.33 (0.74) | -0.07 (0.82) | F = 25.80** |

| Marital status (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.64 | χ2 = 29.66** |

| Medical conditions | 0.92 (1.07) | 1.15 (1.26) | 0.74 (0.97) | 0.90 (1.01) | F = 3.72* |

| Obesity (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.11 | χ2 = 23.43** |

| Smoking status (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.38 | χ2 = 57.38** |

| Physical activity | 1.25 (1.25) | 1.03 (1.13) | 1.41 (1.20) | 1.04 (1.14) | F = 6.01** |

| Depressive symptoms | 17.77 (12.61) | 22.81 (13.51) | 18.19 (12.21) | 20.43 (13.15) | F = 5.32** |

| Avoidance coping | 4.37 (2.92) | 6.14 (3.58) | 4.67 (3.07) | 5.44 (3.21) | F = 11.88** |

| No. of close friends | 2.80 (1.35) | 2.84 (1.37) | 3.00 (1.26) | 2.97 (1.20) | F = 1.69 |

| Quality of friend support | 16.59 (4.70) | 16.18 (4.99) | 17.42 (4.48) | 17.20 (4.56) | F = 2.81* |

Notes: No. = number; df for F = 3, 1117; df for χ2 = 3.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 3.

Results of multiple logistic regression analyses with each baseline covariate as a predictor of 20-year total mortality (N = 1,121)

| Covariates | Odds ratio | [95% CI] |

| Age | 1.09** | [1.05, 1.14] |

| Gender (female = 0, male = 1) | 2.24** | [1.74, 2.89] |

| Socioeconomic status (standardized scale) | 0.55** | [0.48, 0.64] |

| Marital status (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.71* | [0.54, 0.92] |

| Medical conditions | 1.72** | [1.52, 1.95] |

| Obesity (no = 0, yes = 1) | 1.75* | [1.14, 2.68] |

| Smoking status (no = 0, yes = 1) | 3.50** | [2.63, 4.66] |

| Physical activity | 0.83** | [0.75, 0.92] |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.01* | [1.002, 1.02] |

| Avoidance coping | 1.05* | [1.007, 1.09] |

| No. of close friends | 0.93 | [0.85, 1.02] |

| Quality of friend support | 0.97* | [0.95, 0.99] |

Notes: CI = confidence interval; no. = number.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Planned comparisons

Drinking pattern among high-level drinkers.

First, we compared 20-year mortality odds between individuals with regular versus heavy episodic drinking patterns whose average level of drinking was high, that is, Group 3 (reference group) and Group 4 in Table 1. After we adjusted for the covariates among average high drinkers, individuals with regular (score = 0) versus heavy episodic (score = 1) drinking patterns did not differ significantly in 20-year mortality odds (OR = 1.12, p = .53, 95% CI [0.78, 1.60]). The interaction of gender with the comparison of regular to heavy episodic drinking among high drinkers in predicting mortality was not significant (OR = 1.29, p = .48, 95% CI [0.64, 2.56]).

Drinking level among drinkers with a regular pattern.

Next, we compared 20-year mortality odds between individuals with average moderate versus average high drinking whose pattern of drinking was regular, that is, Group 1 (reference group) and Group 3 in Table 1. After we adjusted for the covariates among individuals maintaining a regular drinking pattern, an average high (score = 1) drinking level, compared with an average moderate (score = 0) drinking level, was associated with significantly greater odds of total mortality during the 20-year period (OR = 1.73, p < .01, 95% CI [1.20, 2.47]). Because the planned comparisons were not orthogonal, we reexamined this effect with a Bonferroni correction; the effect remained significant at the .01 level. The interaction of gender with the comparison of moderate to high drinking levels among regular drinkers in predicting mortality was not significant (OR = 0.96, p = .91, 95% CI [0.45, 2.03]). The interaction of baseline medical conditions with the comparison of moderate to high drinking levels was significant (OR = 0.68, p < .05, 95% CI [0.48, 0.96]), with drinking level more strongly linked to mortality among regular drinkers with fewer medical conditions.

Drinking level among drinkers with a heavy episodic pattern.

Finally, we compared 20-year mortality odds between individuals with average moderate versus average high drinking levels whose pattern of drinking was heavy episodic, that is, Group 2 (reference group) and Group 4 in Table 1. After we adjusted for the covariates among individuals engaging in a heavy episodic drinking pattern, average moderate (score = 0) versus average high (score = 1) drinking levels did not differ significantly in 20-year mortality odds (OR = 0.99, p = .96, 95% CI [0.54, 1.79]). The interaction of gender with the comparison of moderate to heavy drinking among heavy episodic drinkers in predicting mortality was not significant (OR = 1.94, p = .35, 95% CI [0.49, 7.77]).

Discussion

The present study systematically examined the combined roles of drinking level and drinking pattern in 20-year total mortality among late-life drinkers. We applied established NIAAA definitions of drinking behavior, had a 20-year follow-up, included both women and men, and used a robust set of covariates. In previous research with the present sample, we found that, when the level of drinking is moderate, the pattern of drinking is significantly related to mortality (Holahan et al., 2014). Integrating this finding with those of the present study provides a comprehensive picture of the combined roles of drinking level and drinking pattern in 20-year mortality among late-life drinkers. Individuals who limit themselves to both a moderate level and a regular pattern of drinking show a longevity advantage over individuals who engage in either a high level or a heavy episodic pattern of drinking.

These results extend our previous research (Holahan et al., 2014) and the research of other investigators (Mukamal et al., 2005; Rehm et al., 2001; Roerecke et al., 2011) who have shown that, in the context of average moderate drinking, individuals who engage in heavy episodic drinking have significantly increased mortality risk compared with regular drinkers. These results also reinforce and extend to all-cause mortality the results of Schoenborn et al. (2014), who found that episodic heavy drinking was associated with increased odds of dying from liver disease among light and moderate drinkers but not among heavier drinkers. More broadly, these findings are consistent with NIAAA guidelines (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007), which emphasize that low-risk drinking requires avoiding both high average consumption and heavy episodic drinking.

The fact that mortality odds for individuals at risk by exceeding guidelines on one risk factor (either a high level of drinking or a heavy episodic pattern of drinking) do not differ from individuals who exceed guidelines on both risk factors should not be interpreted as evidence that engaging in one risk factor makes the other risk factor unimportant. The level and pattern of drinking are strongly associated. As the pattern of drinking goes from regular to heavy episodic, the percentage of individuals who are high-level drinkers almost doubles (44% to 84%). Correspondingly, as the level of drinking goes from moderate to high, the percentage of individuals who are heavy episodic drinkers increases more than three times (17% to 56%). Thus, the role of the additional risk factor is already reflected in the mortality odds of individuals exceeding one risk factor.

Several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the present findings. These are not experimental findings and do not provide evidence of causality. Although we controlled for a wide range of confounding factors, there may be other factors associated with alcohol consumption that remained uncontrolled (see Naimi et al., 2013). Moreover, imperfect operationalization of the factors we did control leaves room for residual confounding. Also, although mortality was indexed objectively, our measures of alcohol consumption were based on self-report. Future research would be strengthened by including objective indices or collateral information on alcohol use. In addition, we did not consider the effects of changes in alcohol consumption over time. Similarly, there is potential variability in the drinking pattern that is not captured by our operationalization of heavy episodic drinking. More detailed examination of differences in time of onset, duration, and frequency of heavy episodic drinking could further enhance prediction of mortality outcomes.

Research on alcohol and mortality has emphasized average consumption, overlooking the role of drinking pattern in mortality (Naimi et al., 2013; Wannamethee, 2013). Risk profiles based only on average alcohol consumption incorrectly estimate mortality risk for many drinkers (Plunk et al., 2014). Heavy episodic drinking is frequent among middle-aged and older adults (Blazer & Wu, 2009). Episodes of heavy drinking are linked to cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cirrhosis of the liver (Rehm et al., 2010). In addition, heavy episodic drinking is associated with suicide, motor vehicle accidents, accidental falls, and violence (Graff-Iversen et al., 2013; Roerecke & Rehm, 2010). This pattern of drinking may be especially risky for older adults because of age-related elevations in comorbidities and medication use (Barnes et al., 2010).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Bernice Moos for her contribution in setting up and developing the data files and John G. Hixon for advice in conducting the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA15685 and by Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service funds. The opinions expressed here are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Barnes A. J., Moore A. A., Xu H., Ang A., Tallen L., Mirkin M., Ettner S. L. Prevalence and correlates of at-risk drinking among older adults: The Project SHARE study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:840–846. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G., Wu L. T. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Moos R. H. Life stressors, social resources, and late-life problem drinking. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:491–501. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos R. H. Patterns and predictors of late-life drinking trajectories: A 10-year longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:254–264. doi: 10.1037/a0018592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S., Moos R. H. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:308–321. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez P. R., Nelson D. E., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D. Impact of a new gender-specific definition for binge drinking on prevalence estimates for women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40:468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Castelnuovo A., Costanzo S., Bagnardi V, Donati M. B., Iacoviello L., de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: An updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Iversen S., Jansen M. D., Hoff D. A, Hoiseth G., Knudsen G. P., Magnus P., Tambs K. Divergent associations of drinking frequency and binge consumption of alcohol with mortality within the same cohort. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2013;67:350–357. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzerath L., Faden V, Zakhari S., Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:829–847. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128382.79375.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. H., Cronkite R., Moos R. Physical activity, exercise coping, and depression in a 10-year cohort study of depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Holahan C. K., Moos B. S., Moos R. H. Late-life alcohol consumption and 20-year mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1961–1971. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P L., Holahan C. K., Moos R. H. Episodic heavy drinking and 20-year total mortality among late-life moderate drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1432–1438. doi: 10.1111/acer.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauhanen J., Kaplan G. A., Goldberg D. E., Salonen J. T. Beer binging and mortality: Results from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study, a prospective population based study. BMJ. 1997;315:846–851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7112.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laatikainen T., Manninen L., Poikolainen K., Vartiainen E. Increased mortality related to heavy alcohol intake pattern. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:379–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H. Coping Responses Inventory: Adult Form Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P L., Moos B. S. Short-term processes of remission and nonremission among late-life problem drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15:948–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S. High-risk alcohol consumption and late-life alcohol use problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1985–1991. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Cronkite R. C., Finney J. W. Health and Daily Living Form Manual. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Moos B. S. Life Stressors and Social Resources Inventory: Adult Form Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Moos B. S. Older adults’ alcohol consumption and late-life drinking problems: A 20-year perspective. Addiction. 2009;104:1293–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Moos B. S. Late-life and life history predictors of older adults’ high-risk alcohol consumption and drinking problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal K. J., Maclure M., Muller J. E., Mittleman M. A. Binge drinking and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:3839–3845. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.574749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Blanchette J., Nelson T. F., Nguyen T., Oussayef N., Heeren T. C., Xuan Z. A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Xuan Z., Brown D. W., Saitz R. Confounding and studies of ‘moderate’ alcohol consumption: The case of drinking frequency and implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108:1534–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide (updated) Bethesda, MD: Author; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07–3769. [Google Scholar]

- Plunk A. D., Syed-Mohammed H., Cavazos-Rehg P., Bierut L. J., Grucza R. A. Alcohol consumption, heavy drinking, and mortality: Rethinking the j-shaped curve. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:471–78. doi: 10.1111/acer.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Baliunas D., Borges G. L. G., Graham K., Irving H., Kehoe T., Taylor B. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: An overview. Addiction. 2010;105:817–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Greenfield T. K., Rogers J. D. Average volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking, and all-cause mortality: Results from the US National Alcohol Survey. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153:64–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Mathers C., Popova S., Thavorncharoensap M., Teerawattananon Y., Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373:2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M., Greenfield T. K., Kerr W. C., Bondy S., Cohen J., Rehm J. Heavy drinking occasions in relation to ischaemic heart disease mortality—an 11–22 year follow-up of the 1984 and 1995 US National Alcohol Surveys. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;40:1401–1410. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M., Rehm J. Irregular heavy drinking occasions and risk of ischemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171:633–644. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn C. A., Stommel M., Ward B. W. Mortality risks associated with average drinking level and episodic heavy drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2014;49:1250–1258. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.891620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte K. K., Moos R. H., Brennan P. L. Predictors of untreated remission from late-life drinking problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:354–362. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M., Roeber J., Kanny D., Brewer R. D., Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11 doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. 130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee S. G. Significance of frequency patterns in ‘moderate’ drinkers for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108:1545–1547. doi: 10.1111/add.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]