Abstract

Objective:

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is associated with elevated risk of early marijuana use and cannabis use disorder (CUD). Both the prevalence of CSA and the course of marijuana use differ between African Americans and European Americans. The current study aimed to determine whether these differences manifest in racial/ ethnic distinctions in the association of CSA with early and problem use of marijuana.

Method:

Data were derived from female participants in a female twin study and a high-risk family study of substance use (n = 4,193, 21% African-American). Cox proportional hazard regression analyses using CSA to predict initiation of marijuana use and progression to CUD symptom(s) were conducted separately by race/ethnicity. Sibling status on the marijuana outcome was used to adjust for familial influences.

Results:

CSA was associated with both stages of marijuana use in African-American and European-American women. The association was consistent over the risk period (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.57, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.37, 1.79] for initiation; HR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.21, 1.88] for CUD symptom onset) in European-American women. In African-American women, the HRs for initiation were 2.52 (95% CI [1.52, 4.18]) before age 15, 1.82 (95% CI [1.36, 2.44]) at ages 15–17, and nonsignificant after age 17. In the CUD symptom model, CSA predicted onset only at age 21 and older (HR = 2.17, 95% CI [1.31, 3.59]).

Conclusions:

The association of CSA with initiation of marijuana use and progression to problem use is stable over time in European-American women, but in African-American women, it varies by developmental period. Findings suggest the importance of considering race/ethnicity in prevention efforts with this high-risk population.

An estimated one in five women in the United States has experienced childhood sexual abuse (CSA; Bensley et al., 2000; Dube et al., 2003; Molnar et al., 2001), and some evidence indicates that Africans Americans are disproportionally affected (Hussey et al., 2006; McCutcheon et al., 2010; Ullman & Filipas, 2005). Women with a history of CSA are at increased risk for a wide range of psychiatric disorders (Fergusson et al., 1996a; Molnar et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2002) that include cannabis and other substance use disorders (Kendler et al., 2000; Kilpatrick et al., 2000).

CSA is also associated with early initiation of marijuana use (Bensley et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1997; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2006), a marker of risk for the development of cannabis use disorder (CUD; Anthony & petronis, 1995; King & Chassin, 2007). Early use itself is a health concern as well because it typically means longer than average exposure to marijuana and—even more importantly—exposure during a crucial period of brain development, with the potential for long-term impact on cognitive functioning (Ashtari et al., 2011; Bava & Tapert, 2010) as well as other psychopathology (Volkow et al., 2014).

Early marijuana use and cannabis use disorder in adolescent girls and young women

Nearly half of U.S. adolescents (Johnston et al., 2013) and adults (Degenhardt et al., 2007, 2008) have used marijuana, a figure that is likely to grow with the trend in state legalization of nonmedical use of marijuana. Ten to twenty percent of adult marijuana users meet lifetime Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American psychiatric Association, 1994), diagnostic criteria for cannabis abuse or dependence (Copeland & Swift, 2009; Stinson et al., 2006; Teesson et al., 2006), and evidence from a community-based study of 14- to 24-year-olds suggests that problems develop relatively early in the course of use. More than one third of marijuana users in that study endorsed at least one CUD symptom (Nocon et al., 2006). CUD is associated with elevated risk for use and misuse of other illicit substances (Hall & Lynskey, 2005; Macleod et al., 2004) in addition to physical health problems such as bronchitis and lung damage (Tashkin, 2005; Taylor et al., 2000). Adolescent and young adult female marijuana users face other risks as well, including increased likelihood of experiencing physical or sexual assault (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; Martino et al., 2004; Testa et al., 2003). Marijuana use during the childbearing years presents the additional possibility of fetal exposure to marijuana, which is associated with numerous adverse health outcomes (El Marroun et al., 2009; Minnes et al., 2011). Early initiation of marijuana use and the development of marijuana-related problems in adolescent girls and young women are clearly major public health concerns.

Marijuana use in African Americans versus European Americans

Studies examining potential differences by race/ethnicity in lifetime prevalence of marijuana use have produced inconsistent results (Kosterman et al., 2000; Shih et al., 2010; White et al., 2007). Evidence suggests that the likelihood of progressing to CUD is lower in African-American (AA) than European-American (EA) marijuana users (Chen et al., 2005; Stinson et al., 2006), but patterns of marijuana use and trends in CUD development indicate that African Americans are also vulnerable to problem use. Recent studies have found that AA marijuana users continue to use marijuana later into adulthood than members of other racial/ ethnic groups (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Finlay et al., 2012). Initiation of marijuana use before alcohol use also is more common among AA than EA adolescents and young adults (Guerra et al., 2000; Sartor et al., 2013; White et al., 2007). Furthermore, although current lifetime rates of CUD are lower in African Americans than in European Americans, the prevalence of CUD is growing faster in African Americans than in other racial/ethnic groups (Compton et al., 2004).

Examining risk conferred by childhood sexual abuse in the context of other familial risk factors

Estimating the specific contribution of CSA to marijuana-related outcomes is challenging because of the tendency for CSA to occur in the context of other familial risk factors, such as other forms of child maltreatment (Dube et al., 2006; Fleming et al., 1997; Molnar et al., 2001), parental conflict (Fergusson et al., 1996b; Fleming et al., 1997), and parental alcohol problems (Fergusson et al., 1996b; Fleming et al., 1997; Vogeltanz et al., 1999), that are also associated with risk for early marijuana use (Bensley et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1997) and CUD (Marmorstein et al., 2009; Melchior et al., 2011). Determining if the observed elevation in risk for early and problem marijuana use in individuals exposed to CSA is attributable to sexual abuse specifically or to the constellation of risk factors that cluster with it requires a methodological approach that can tease apart the overlap in these influences. Given the wide range of correlated familial risk factors, measurement of all relevant psychiatric and psychosocial constructs to include in analyses is extremely challenging. The incorporation of information on marijuana use in siblings is an alternative approach. Because members of a twin pair reared together are exposed to nearly all the same familial influences (with a slightly lesser degree of overlap in nontwin siblings), sibling status can be used as a broad latent measure of familial influences on marijuana outcomes.

Building on evidence of a higher prevalence of CSA in AA versus EA women and differences between African Americans and European Americans in the course of marijuana use, we aimed to identify possible distinctions between AA and EA young women in the independent association of CSA with the timing of marijuana use initiation and progression to marijuana-related problems. To address this aim, we applied the sibling approach to adjusting for familial influences on marijuana-related outcomes, using data from a large combined sample of AA and EA young women from a multiwave female twin study and a multiwave high-risk family study.

Method

The studies from which data were drawn, the Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study (MOAFTS) and the Missouri Family Study (MOFAM), were approved by the Human Research Protections Office at Washington University in St. Louis. MOFAM was also approved by the Ethics Board of the State Department of Health and Senior Services (which was not required at the time that MOAFTS began).

Participants

The sample for the current study was composed of female participants from MOFAM with at least one sibling who had also participated in MOFAM and female twin pairs who completed the fourth wave of data collection for MOAFTS.

MOAFTS.

MOAFTS is a longitudinal study of alcohol use and related psychopathology in adolescent girls and young women. Female twins born in Missouri to Missouri-resident parents between 1975 and 1985 were identified through birth records and recruited between 1995 and 1999. Cohorts of 13-, 15-, 17-, and 19-year-old twin pairs and their families were ascertained in the first 2 years, with new cohorts of 13-year-old twins and their families added in the subsequent 2 years. Interviews were completed by at least one parent in 78% of eligible families. (See Waldron et al., 2013, for details on sample ascertainment.)

Baseline (Wave 1) interviews were completed with 3,258 twins. Retest interviews (Wave 3) were conducted with a subset of Wave 1 participants (n = 1,370) 2 years after Wave 1 assessments. Between 2002 and 2005, all twins from the target cohort (excluding those who had withdrawn from the study or whose parents asked that the family not be recontacted) were contacted for Wave 4 interviews. Because all twins were 18 years of age or older at the time of recruitment for Wave 4, parental consent was not needed. As a result, an even greater number of twins completed Wave 4 than Wave 1 interviews: 3,787 (80% of those identified from birth records). Wave 5 interviews were conducted between 2005 and 2008 with 3,428 twins.

Because it resulted in the largest sample size and covered lifetime psychiatric and psychosocial information in young adulthood, Wave 4 interviews were the primary source of data for the current study, but data from other waves of data collection were integrated as well. (Data from at least one other wave of data collection were available for 95.5% of Wave 4 participants.) The Wave 4 sample was composed of 964 monozygotic twin pairs, 809 dizygotic twin pairs, and 241 twins whose co-twins did not participate.

MOFAM.

MOFAM is a high-risk alcoholism family study oversampled for AA families. From 2003 to 2009, Missouri state birth records were used to identify families with at least one female or male child age 13, 15, 17, or 19 years (the same age range targeted in MOAFTS) and one or two additional full siblings. Biological mothers completed brief telephone screening interviews to determine familial level of risk for alcoholism. Families in which biological fathers had a history of excessive drinking were classified as “high risk.” All others were classified as “low risk.” Another group of families was selected from men identified through driving records as having two or more drunk driving convictions (“very high risk”).

In all participating families, mothers were interviewed first. Biological fathers were then solicited for interview, and permission was sought from mothers to recruit offspring. Sample ascertainment is described in detail in a previous publication (Calvert et al., 2010). Three hundred seventeen families of non-AA (primarily EA) descent and 450 AA families (92% of targeted families) were enrolled in the study. Sample enrollment occurred over 6 years. Three of the intake years had sufficient time to collect four waves of data; the remainder had one to two waves. A total of 1,461 (735 female) offspring completed at least one interview.

The total sample size for the current study was 4,193: 3,544 MOAFTS participants (all full twin pairs who completed Wave 4) and 649 female MOFAM participants (all female MOFAM participants with at least one other sibling who participated in MOFAM). Twenty-one percent of the sample self-identified as AA, the remainder as EA. Mean ages at first and last interview were 16.9 (SD = 3.4) and 24.1 (SD = 3.1) years, respectively. CSA history was available for 4,150 participants.

Procedure and assessment battery for MOAFTS and MOFAM

MOFAM and MOAFTS assessments were nearly identical by design to facilitate integration of the data across samples (with adjustments for differences in ascertainment strategies). In both studies, data were collected by trained interviewers using an interview modified for telephone administration from the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz et al., 1994; Hesselbrock et al., 1999). The SSAGA was designed to assess DSM-IV substance use and other psychiatric disorders and related psychosocial domains. With the exception of the Wave 5 MOAFTS interview, which covered the 2 years between Wave 4 and Wave 5 assessments, interviews queried lifetime psychiatric and psychosocial history. Consent was obtained verbally before the start of the interview.

Predictors and outcomes

In cases in which age at first CSA experience, age at first use of marijuana, or age at first CUD symptom onset was reported in more than one assessment, the age reported in the earliest assessment was used.

Childhood sexual abuse.

CSA was queried in Waves 1, 3, and 4 of MOAFTS and all four waves of data collection in MOFAM using the questions listed in Table 1. Items relevant to sexual abuse history appeared in different sections of the interview under different wording. A cutoff of age 15 was chosen, as questions in the Parental Discipline and Childhood Experiences section of the MOAFTS Wave 4 interview referred to the period “before you turned 16.” Age at first occurrence was queried for all items endorsed. Criteria for CSA were met if any sexual abuse question in any wave of data collection was endorsed (as is standard in the child abuse literature) and reported to have occurred at age 15 or younger.

Table 1.

Items used to define childhood sexual abuse in MOAFTS and MOFAM

| Traumatic events (Waves 1, 3, and 4 of MOAFTS; all waves of MOFAM) |

| Endorsement of event 1 or 2, with reported age at first experience 15 years or younger |

| 1. Raped |

| 2. Sexually molested |

| Health problems and health habits (Waves 1, 3, and 4 of MOAFTS; all waves of MOFAM) |

| Endorsement of item, with reported age at first experience 15 years or younger Has anyone ever forced you to have sexual intercourse? |

| Parental discipline and early childhood experiences (Wave 4 of MOAFTS) |

| Endorsement of item 1 or 2 |

| 1. Before you turned 16, was there any forced sexual contact between you and any family member like a parent or stepparent, grandfather, etc.? By sexual contact, I mean their touching your sexual parts, your touching their sexual parts, or intercourse. |

| 2. Before you turned 16, was there any forced sexual contact between you and anyone who was 5 or more years older than you (other than a family member)? |

Notes: MOAFTS = Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study; MOFAM = Missouri Family Study.

The prevalence of CSA was 23.5% in African Americans and 11.8% in European Americans. Mean age at first CSA experience was 9.0 years (SD = 3.7) in African Americans and 8.8 years (SD = 4.1) in European Americans. In the AA subsample, 66.8% neither endorsed CSA nor had a participating sibling who did, 9.6% did not endorse CSA but had a sibling who did, 13.3% endorsed CSA but her sibling(s) did not, and 10.3% both endorsed CSA and had a sibling who did. The corresponding rates in the EA subsample were as follows: 82.2% (neither), 6.0% (sibling only), 6.2% (participant only), and 5.6% (participant and sibling).

Age at first use of marijuana.

Respondents who endorsed any marijuana use were asked their age at first use. Because there is no standard definition of early initiation of marijuana use, we chose the lowest third of the age at initiation distribution (age 15 or younger) to represent early use relative to same-sex peers.

Age at onset of first cannabis use disorder symptom.

Individuals who endorsed one or more DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for either cannabis abuse or cannabis dependence were considered positive for CUD symptom(s). Age at first CUD symptom onset was derived from reported age(s) that each endorsed symptom was first experienced. (Cannabis abuse but not dependence symptoms were assessed in Waves 1 and 3 of MOAFTS, but both abuse and dependence symptoms were assessed in Waves 4 and 5. Age at onset of cannabis abuse symptoms was not queried in MOFAM. Therefore, age at onset of CUD symptoms in MOFAM participants was derived from reported age[s] at onset of cannabis dependence symptom[s], thus potentially resulting in an underestimate of the earliness of CUD symptom onset in some MOFAM participants. Of note, only 12 MOFAM participants endorsed abuse but never reported dependence symptoms.)

Familial influences.

To adjust for familial influences on initiation of marijuana use, we created a dichotomous indicator of sibling early (age 15 or younger) age at first marijuana use (i.e., an indicator of risky marijuana use). A dichotomous variable representing sibling CUD symptom status was used to represent familial influences on marijuana-related problems. We opted to use dichotomous variables to allow for a more straightforward interpretation of results involving the splitting of risk periods in Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression models (see Data Analysis). In MOAFTS, sibling status was derived from the co-twin’s self-report. In MOFAM, it was derived from self-reports from all participating siblings (i.e., female and/ or male siblings) and was coded positive if any sibling endorsed early use/CUD symptoms.

Data analysis

Marijuana use, problem use, and timing of transitions by race/ethnicity and childhood sexual abuse history.

Chi-square tests of association were conducted to test for differences in rates of lifetime use and (one or more) CUD symptoms by race/ethnicity and by CSA status within the AA and EA subsamples. Independent t tests were conducted to test for differences in age at first use, age at onset of first CUD symptom, rate of progression from first use to first symptom by race/ethnicity, and by CSA status within the AA and EA subsamples.

Predicting initiation of marijuana use and onset of cannabis use disorder symptoms with childhood sexual abuse history.

Cox PH regression analyses were conducted to predict initiation of marijuana use and onset of CUD symptoms as a function of CSA status. Age at first marijuana use was the point of origin in the symptom onset analyses. Cox PH regression analyses account for the possibility that participants who have not yet experienced the event of interest may do so in the future. Under this approach, data up until the time of censoring (in this case, the most recent interview) are used in the calculation of hazard ratios (HRs). Tests of the PH assumption that risk remains constant over time can reveal the extent to which risk associated with CSA varies across the period of risk (e.g., whether CSA is a predictor specifically of early initiation of marijuana use). We modeled CSA as a time-varying covariate by creating a “person year” data set in SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). CSA status was coded as negative in each year before the age at first occurrence and positive for that year and each subsequent year. Analyses were conducted in Stata Version 9.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) using the clustered sandwich estimator to adjust for the nonindependence of observations in siblings.

Given the evidence for differences by race/ethnicity in rates of CSA and likelihood of developing CUD symptoms among marijuana users (see Results) and our interest in further developing etiological models of marijuana use and problem use in AA young women, modeling was conducted separately for the AA and EA subsamples. In addition to including the sibling status variable to adjust for familial influences, all analyses were adjusted for sample ascertainment using three dummy variables to represent the high-risk, low-risk, and very-high-risk MOFAM groups (with MOAFTS as the comparison group) and for age at the time of the interview in which the marijuana outcome was first reported. (For participants who did not endorse the outcome, age at report was coded as age at the last interview, i.e., age they last reported never using marijuana/meeting CUD criteria.) The CUD symptom onset analyses also included age at first marijuana use as a covariate.

The PH assumption was tested with the Grambsch and Therneau test of the Schoenfeld residuals (Grambsch & Therneau, 1994). PH violations would indicate that the association of these variables with risk for the marijuana outcome varies by period of risk (i.e., age). In models with PH violations for CSA or sibling status, HRs were reported by risk period. (A detailed description of corrections for violations of the PH hazards assumption in the final models is available on request.)

Results

Marijuana use, problem use, and timing of transitions by race/ethnicity

The lifetime prevalence of marijuana use was 55.8% in the AA subsample and 51.9% in the EA subsample, χ2(1) = 4.27, p = .039. Mean age at first marijuana use did not differ significantly across the racial/ethnic groups: 16.7 (SD = 2.7) and 16.8 (SD = 2.5) in the AA and EA subsamples, respectively, t(721) = 0.97, p = .333. A higher proportion of AA than EA marijuana users developed one or more symptoms of CUD (38.9% vs. 25.8%), χ2(1) = 31.39, p < .001). The mean age at onset of first CUD symptom was significantly higher in the AA than EA subsample (18.2 [SD = 3.0] vs. 17.2 [SD = 2.5]), t(286) = 3.84, p < .001, but mean transition time from first use to symptom onset did not vary by race/ ethnicity (2.3 [SD = 2.3] years in AA and 2.0 [SD = 2.0] years in EA participants), t(280) = 1.62, p = .107.

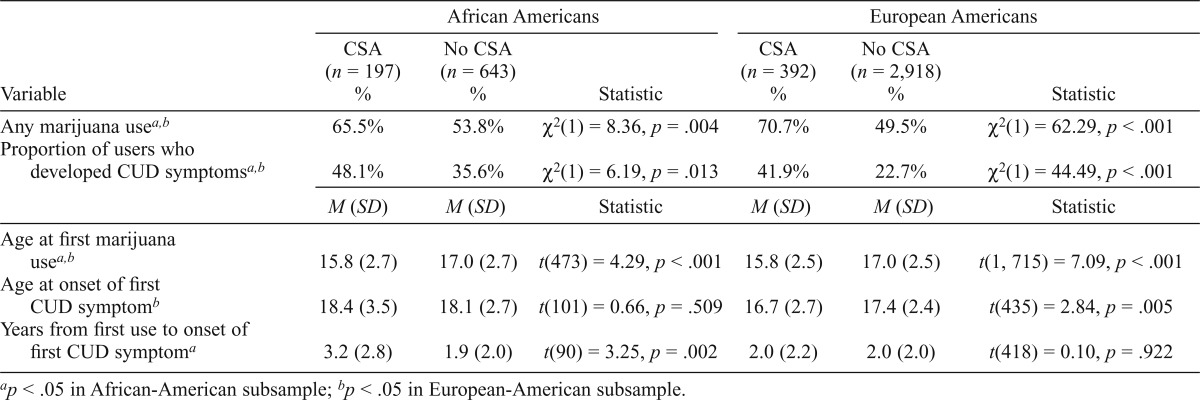

Marijuana use, problem use, and timing of transitions by race/ethnicity and childhood sexual abuse history

Results of preliminary analyses testing for differences by race/ethnicity in the association of CSA with marijuana use are shown in Table 2. Across racial/ethnic groups, women with a history of CSA were more likely to use marijuana, develop CUD symptoms, and start using marijuana at an early age than were women without a history of CSA. EA women with a history of CSA reported a younger age at symptom onset than EA women without a history of CSA, but no differences by CSA status were observed in AA women. However, in the AA subsample, the transition time from first use to symptom onset was more than a year longer in women with versus without a history of CSA. No group differences in transition times were found in EA women.

Table 2.

Prevalence of marijuana use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptoms and timing of transitions to first use and symptom onset by race/ethnicity and childhood sexual abuse (CSA) history

| Variable | African Americans |

European Americans |

||||

| CSA (n = 197) % | No CSA (n = 643) % | Statistic | CSA (n = 392) % | No CSA (n = 2,918) % | Statistic | |

| Any marijuana usea,b | 65.5% | 53.8% | χ2(1) = 8.36, p = .004 | 70.7% | 49.5% | χ2(1) = 62.29, p < .001 |

| Proportion of users who developed CUD symptomsa,b | 48.1% | 35.6% | χ2(1) = 6.19, p = .013 | 41.9% | 22.7% | χ2(1) = 44.49, p < .001 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Statistic | M (SD) | M (SD) | Statistic | |

| Age at first marijuana usea,b | 15.8 (2.7) | 17.0 (2.7) | t(473) = 4.29, p < .001 | 15.8 (2.5) | 17.0 (2.5) | t(1, 715) = 7.09, p < .001 |

| Age at onset of first CUD symptomb | 18.4 (3.5) | 18.1 (2.7) | t(101) = 0.66, p = .509 | 16.7 (2.7) | 17.4 (2.4) | t(435) = 2.84, p = .005 |

| Years from first use to onset of first CUD symptoma | 3.2 (2.8) | 1.9 (2.0) | t(90) = 3.25, p = .002 | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.0) | t(418) = 0.10, p = .922 |

p < .05 in African-American subsample;

p < .05 in European-American subsample.

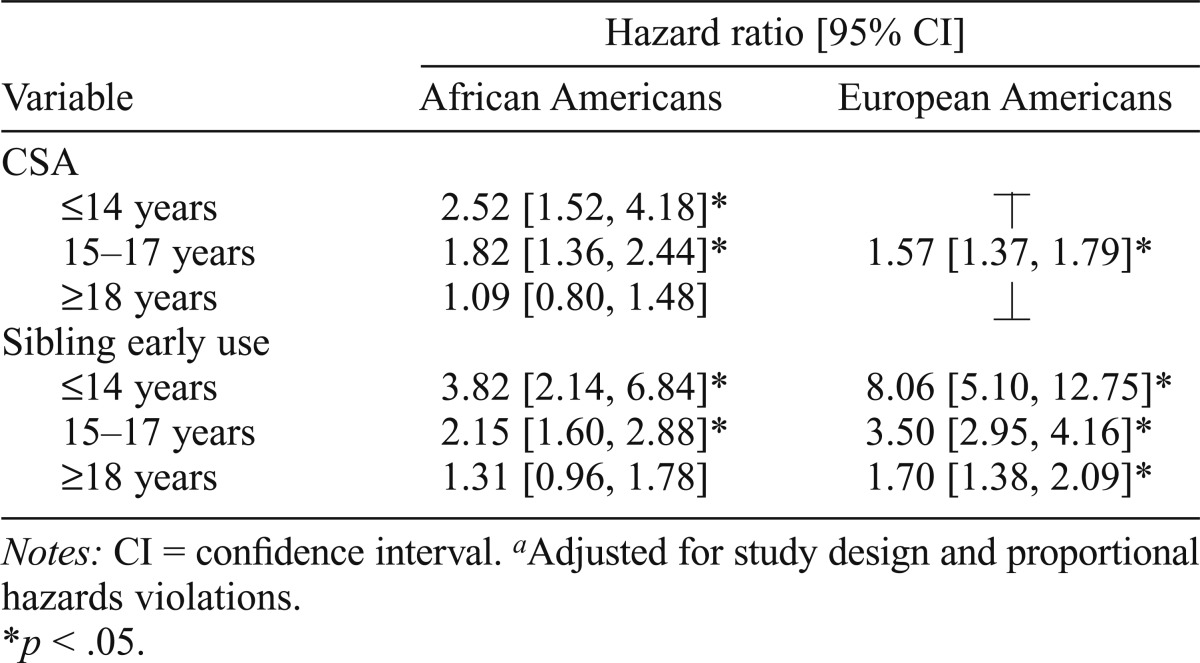

Predicting initiation of marijuana use with childhood sexual abuse history

Results of Cox PH regression analyses using CSA history to predict marijuana use are shown by race/ethnicity in Table 3. Both AA and EA models were corrected for PH violations for CSA, age at the time first marijuana use was reported, and sibling early use. After adjusting for the substantial contribution of familial influences to risk for early use (represented in the models with sibling early use status), we found evidence for an independent contribution of CSA to risk for marijuana use across adolescence and young adulthood in EA women (HR = 1.57, 95% CI [1.37, 1.79]) but exclusively during adolescence in AA women. In the AA model, HRs for marijuana use before age 15 and from ages 15 to 17 were 2.52 (95% CI [1.52, 4.18]) and 1.82 (95% CI [1.36, 2.44]), respectively, with no significant association thereafter.

Table 3.

Results of Cox proportional hazards regression analyses using childhood sexual abuse (CSA) history to predict marijuana usea

| Variable | Hazard ratio [95% CI] |

|

| African Americans | European Americans | |

| CSA | ||

| ≤ 14 years | 2.52 [1.52, 4.18]* | ⊤ |

| 15–17 years | 1.82 [1.36, 2.44]* | 1.57 [1.37, 1.79]* |

| ≥ 18 years | 1.09 [0.80, 1.48] | ⊥ |

| Sibling early use | ||

| ≤ 14 years | 3.82 [2.14, 6.84]* | 8.06 [5.10, 12.75]* |

| 15–17 years | 2.15 [1.60, 2.88]* | 3.50 [2.95, 4.16]* |

| ≥ 18 years | 1.31 [0.96, 1.78] | 1.70 [1.38, 2.09]* |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for study design and proportional hazards violations.

p < .05.

Predicting progression from first marijuana use to cannabis use disorder symptom onset with childhood sexual abuse history

Results of Cox PH regression analyses using CSA history to predict progression from first marijuana use to CUD symptom onset, adjusting for familial influences on risk for CUD symptom development, are shown by race/ethnicity in Table 4. The models were corrected for PH violations for age at the time first CUD symptom was reported and age at first marijuana use in both AA and EA models, CSA in the AA model, and sibling CUD symptom status in the EA model. In the AA subsample, CSA was associated with progression to CUD symptoms at ages 21 and older (HR = 2.17, 95% CI [1.31, 3.59]) but not before age 21. By contrast, risk conferred by CSA to progression to CUD symptoms in the EA subsample was constant over the period of risk (HR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.21, 1.88]).

Table 4.

Results of Cox proportional hazards regression analyses using childhood sexual abuse (CSA) history to predict rate of transition from first marijuana use to first cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptoma

| Variable | HR [95% CI] |

|

| African Americans | European Americans | |

| CSA | ||

| ≤ 20 years | 1.04 [0.69, 1.59] | ⊤ |

| ≥ 21 years | 2.17 [1.31, 3.59]* | 1. 5 1 [ 1 . 21, 1.88]* |

| Sibling CUD symptoms | ⊥ | |

| ≤ 17 years | ⊤ | 1.14 [0.82, 1.60] |

| 18–20 years | 1.91 [1.34, 2.72]* | 2.50 [1.81, 3.45]* |

| ≥ 21 years | ⊥ | 2.23 [1.27, 3.90]* |

Notes: HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for study design, proportional hazards violations, and age at first marijuana use.

p < .05.

Discussion

The current study expanded the limited literature on racial/ethnic differences in rates of marijuana use and related problems and prevalence of CSA by examining the association of CSA with the developmental course of marijuana use. Our findings indicated that the association between CSA and the timing of first use and progression to problem use in AA women varies by developmental period, but in EA women, risk conferred by CSA is stable over time for both stage transitions. We also found evidence of higher rates of CSA, lifetime prevalence of marijuana use, and likelihood of developing marijuana-related problems in AA than EA women.

Early and problem marijuana use in African-American versus European-American young women

Although a slightly greater proportion of AA than EA women endorsed some use of marijuana, age at first marijuana use did not differ between the groups. Comparisons across racial/ethnic groups in age at initiation have rarely been reported in the literature, but in the one known study to do so, no difference between African Americans and European Americans was observed (White et al., 2007). Findings from the few studies to examine racial/ethnic differences in lifetime marijuana use are mixed. Whereas White et al. (2007) and Kosterman et al. (2000) reported higher rates in African Americans than in European Americans, Shih et al. (2010) did not find any differences between racial/ethnic groups. Contrary to prior studies showing the same or even lower likelihood of progression to CUD in AA compared with EA marijuana users (Chen et al., 2005; Stinson et al., 2006), we found that a significantly larger proportion of AA than EA marijuana users developed CUD symptoms. This may be due in part to the lower threshold we used to define problem use. The possibility that a less severe syndrome of marijuana-related problems is more commonly found in African Americans merits further investigation.

Childhood sexual abuse and marijuana outcomes in African-American versus European-American women

Although the prevalence of CSA in AA women was twice that in EA women, the association of CSA with marijuana outcomes was similar in several ways across the racial/ethnic groups. Consistent with an extensive literature linking CSA to early and problem use of marijuana (Bensley et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1997; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2006), the likelihood of ever using marijuana, using marijuana at a young age, and developing CUD symptoms was elevated in both AA and EA women with a history of CSA. Regression analyses incorporating sibling status on marijuana outcomes revealed that the contribution of CSA to risk for use and development of CUD symptoms in both racial/ethnic groups was independent of familial risk factors common to exposure to CSA and early (or problem) marijuana use. That is, the association cannot be fully explained by risk factors such as familial conflict, other forms of child maltreatment, or parental alcohol problems that are more common in families of children who have experienced sexual abuse (Dube et al., 2006; Fergusson et al., 1996b; Fleming et al., 1997; Molnar et al., 2001; Vogeltanz et al., 1999).

The primary difference we observed between AA and EA women was in the relative stability of the association between CSA and transitions through stages of marijuana use. Whereas CSA conferred a modest but significant increase in risk for use (57%) and progression to problem use (51%) in EA women across the period of risk for each outcome, the association between CSA and marijuana outcomes varied by developmental period in AA women. Before age 15, a two and a half–fold increase in risk for initiation of marijuana use was observed in AA women with a history of CSA; from ages 15 to 17, the increase in risk was 82%. No association with CSA was observed for initiation of marijuana use at age 18 or older.

The adolescence-specific risk in AA but not EA women may be explained in part by the somewhat higher prevalence of lifetime marijuana use among African Americans in this sample. In an environment where marijuana use is normative, it may not be as closely linked to an adverse event such as CSA than it would be in an environment where marijuana use is viewed as deviant or problematic. However, the consistency across racial/ethnic groups in the earlier (and nearly identical) age at first marijuana use in women with a history of CSA does not support this hypothesis and, as noted earlier, the higher prevalence of marijuana use in AA than in EA women has not been consistently found in prior studies. Therefore, this pattern of results cannot be easily explained.

For the transition to problem use, CSA-associated risk was limited to age 21 and older in AA women, with CSA conferring a greater than twofold increase in risk for progression from first use to CUD symptom at age 21 and older but not before that time. This distinction from the stable association with CSA observed in EA women may be attributable in part to the older age at onset of first CUD symptom in AA than in EA women (18.2 years vs. 17.2 years). That is, the peak period of risk—independent of CSA history—is older in AA than in EA women, so the risk conferred by CSA does not manifest until later in development.

The lower estimate of familial influences on initiation of marijuana use before mid-adolescence in AA versus EA young women merits comment as well. It suggests that risk factors shared by family members (e.g., parental psychopathology, genetic risk of CUD) contribute to a lesser degree to early initiation of marijuana use in AA versus EA young women. Higher rates of certain protective factors in AA than in EA families (e.g., religiosity; Taylor et al., 1996) may partially explain this distinction. It may also be that the most robust risk factors for initiation of marijuana use in AA girls are nonfamilial. The possibility that familial influences were not as well captured in the AA versus EA subsample should also be considered, given that a larger proportion of AA participants were nontwin siblings drawn from MOFAM. Follow-up analyses using measured psychiatric and psychosocial covariates are planned with the current sample to tease apart these possibilities.

Limitations

Certain limitations should be considered in interpreting these study findings. First, sibling status on early initiation and problem use of marijuana only approximates familial risk; it does not capture all of the variance attributable to the full spectrum of risk and protective factors associated with both CSA and early and problem use of marijuana. Second, sibling status on marijuana outcomes was derived from male as well as female siblings who took part in MOFAM but only female co-twins in MOAFTS. Third, the rates of marijuana use, marijuana-related problems, and associated risk factors are elevated in families at high risk for alcoholism. Thus, inclusion of the “high-risk” and “very-high-risk” MOFAM participants may have resulted in a slightly higher estimate of the prevalence of CSA, marijuana use, and CUD symptoms in the current study compared with the general population. However, because there is no evidence that the association of CSA with marijuana outcomes differs between high-risk and general populations, inclusion of MOFAM participants does not reduce generalizability of the main study findings.

Strengths and future directions

Several features of this study distinguish it from prior work in this area, including the substantial representation of African Americans in a large all-female sample, the assessment of CSA using multiple questions in different sections of the interview (and for most participants, at more than one point in time), and the use of self-reported data from siblings to adjust for familial influences common to CSA and marijuana use. Our findings highlight the need for additional research that will enhance our understanding of the etiology of marijuana-related problems and improve intervention efforts with girls who have experienced sexual abuse. Future studies aimed at refining etiological models of problem use of marijuana should involve characterization of patterns of marijuana use at a fine-grain level, including context as well as quantity and frequency of use. Examining the association of CSA with the progression of marijuana use in women of other racial/ethnic backgrounds is another important next step, as it can inform the development of culturally tailored interventions for this high-risk population.

Footnotes

This study was funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants AA017921, AA09022, AA011998, AA017688, AA017915, AA021492, and AA12640; National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants DA23668 and DA32573; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD049024; and a grant from the Robert E. Leet and Clara Guthrie patterson Trust.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony J. C., Petronis K. R. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashtari M., Avants B., Cyckowski L., Cervellione K. L., Roofeh D., Cook P., Kumra S. Medial temporal structures and memory functions in adolescents with heavy cannabis use. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bava S., Tapert S. F. Adolescent brain development and the risk for alcohol and other drug problems. Neuropsychology Review. 2010;20:398–413. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley L. S., Spieker S. J., Van Eenwyk J., Schoder J. Selfreported abuse history and adolescent problem behaviors. II. Alcohol and drug use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley L. S., Van Eenwyk J., Simmons K. W. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz K. K., Cadoret R., Cloninger C. R., Dinwiddie S. H., Hessel-brock V. M., Nurnberger J. I., Jr., Schuckit M. A. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert W. J., Keenan Bucholz K., Steger-May K. Early drinking and its association with adolescents’ participation in risky behaviors. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2010;16:239–251. doi: 10.1177/1078390310374356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Y., O’Brien M. S., Anthony J. C. Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Jacobson K. C. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton W. M., Grant B. F., Colliver J. D., Glantz M. D., Stinson F. S. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J., Swift W. Cannabis use disorder: Epidemiology and management. International Review of Psychiatry. 2009;21:96–103. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Chiu W. T., Sampson N., Kessler R. C., Anthony J. C. Epidemiological patterns of extra-medical drug use in the United States: Evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 2001–2003. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Chiu W. T., Sampson N., Kessler R. C., Anthony J. C., Angermeyer M., Wells J. E. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5(7):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S. R., Felitti V J., Dong M., Giles W, H., Anda R. F. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S. R., Miller J. W, Brown D. W., Giles W. H., Felitti V J., Dong M., Anda R. F. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:444. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H., Tiemeier H., Steegers E. A. P., Jaddoe V. W. V., Hofman A., Verhulst F. C., Huizink A. C. Intrauterine cannabis exposure affects fetal growth trajectories: The Generation R Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1173–1181. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bfa8ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Horwood L. J., Lynskey M. T. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996a;35:1365–1374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Lynskey M. T., Horwood L. J. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996b;35:1355–1364. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay A. K., White H. R., Mun E. Y, Cronley C. C., Lee C. Racial differences in trajectories of heavy drinking and regular marijuana use from ages 13 to 24 among African-American and White males. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J., Mullen P., Bammer G. A study of potential risk factors for sexual abuse in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch P., Therneau T. M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra L. M., Romano P. S., Samuels S. J., Kass P. H. Ethnic differences in adolescent substance initiation sequences. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154:1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. D., Lynskey M. Is cannabis a gateway drug? Testing hypotheses about the relationship between cannabis use and the use of other illicit drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24:39–48. doi: 10.1080/09595230500126698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. A., Fulkerson J. A., Beebe T. J. Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock M., Easton C., Bucholz K. K., Schuckit M., Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA—a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey J. M., Chang J. J., Kotch J. B. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E. Monitoring the Future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2012. Volume I: Secondary School students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., Bulik C. M., Silberg J., Hettema J. M., Myers J., Prescott C. A. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Acierno R., Resnick H. S., Saunders B. E., Best C. L. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Acierno R., Saunders B., Resnick H. S., Best C. L., Schnurr P. P. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K. M., Chassin L. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:256–265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R., Hawkins J. D., Guo J., Catalano R. F., Abbott R. D. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J., Oakes R., Copello A., Crome I., Egger M., Hickman M., Smith G. D. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: A systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet. 2004;363:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein N. R., Iacono W. G., McGue M. Alcohol and illicit drug dependence among parents: Associations with offspring externalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:149–155. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S. C., Collins R. L., Ellickson P. L. Substance use and vulnerability to sexual and physical aggression: A longitudinal study of young adults. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:521–540. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.521.63684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon V V, Sartor C. E., Pommer N. E., Bucholz K. K., Nelson E. C., Madden P. A., Heath A. C. Age at trauma exposure and PTSD risk in young adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:811–814. doi: 10.1002/jts.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M., Choquet M., Le Strat Y., Hassler C., Gorwood P. Parental alcohol dependence, socioeconomic disadvantage and alcohol and cannabis dependence among young adults in the community. European Psychiatry. 2011;26:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S., Lang A., Singer L. Prenatal tobacco, marijuana, stimulant, and opiate exposure: Outcomes and practice implications. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2011;6:57–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar B. E., Buka S. L., Kessler R. C. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. C., Heath A. C., Lynskey M. T., Bucholz K. K., Madden P. A., Statham D. J., Martin N. G. Childhood sexual abuse and risks for licit and illicit drug-related outcomes: A twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1473–1483. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. C., Heath A. C., Madden P. A. F., Cooper M. L., Dinwiddie S. H., Bucholz K. K., Martin N. G. Association between selfreported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: Results from a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocon A., Wittchen H. U., Pfister H., Zimmermann P., Lieb R. Dependence symptoms in young cannabis users? A prospective epidemiological study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor C. E., Agrawal A., Lynskey M. T., Duncan A. E., Grant J. D., Nelson E. C., Bucholz K. K. Cannabis or alcohol first? Differences by ethnicity and in risk for rapid progression to cannabis-related problems in women. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:813–823. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih R. A., Miles J. N. V, Tucker J. S., Zhou A. J., D’Amico E. J. Racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance use: Mediation by individual, family, and school factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:640–651. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson F. S., Ruan W. J., Pickering R., Grant B. F. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: Prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin D. P. Smoked marijuana as a cause of lung injury. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. 2005;63:93–100. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2005.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. R., Poulton R., Moffitt T. E., Ramankutty P., Sears M. R. The respiratory effects of cannabis dependence in young adults. Addiction. 2000;95:1669–1677. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M., Jayakody R., Levin J. S. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M., Baillie A., Lynskey M., Manor B., Degenhardt L. Substance use, dependence and treatment seeking in the United States and Australia: A cross-national comparison. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Livingston J. A., Vanzile-Tamsen C., Frone M. R. The role of women’s substance use in vulnerability to forcible and incapacitated rape. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:756–764. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman S. E., Filipas H. H. Ethnicity and child sexual abuse experiences of female college students. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2005;14:67–89. doi: 10.1300/J070v14n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeltanz N. D., Wilsnack S. C., Harris T. R., Wilsnack R. W., Won-derlich S. A., Kristjanson A. F. Prevalence and risk factors for childhood sexual abuse in women: National survey findings. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:579–592. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N. D., Baler R. D., Compton W. M., Weiss S. R. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M., Bucholz K. K., Lynskey M. T., Madden P. A. F., Heath A. C. Alcoholism and timing of separation in parents: Findings in a midwestern birth cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:337–348. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. R., Jarrett N., Valencia E. Y., Loeber R., Wei E. Stages and sequences of initiation and regular substance use in a longitudinal cohort of black and white male adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:173–181. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]