Abstract

Objective:

The promotion of drinking behaviors correlates with increased drinking behaviors and intent to drink, especially when peers are the promotion source. Similarly, online displays of peer drinking behaviors have been described as a potential type of peer pressure that might lead to alcohol misuse when the peers to whom individuals feel attached value such behaviors. Social media messages about drinking behaviors on Twitter (a popular social media platform among young people) are common but understudied. In response, and given that drinking alcohol is a widespread activity among young people, we examined Twitter chatter about drinking.

Method:

Tweets containing alcohol- or drinking-related keywords were collected from March 13 to April 11, 2014. We assessed a random sample (n = 5,000) of the most influential Tweets for sentiment, theme, and source.

Results:

Most alcohol-related Tweets reflected a positive sentiment toward alcohol use, with pro-alcohol Tweets outnumbering anti-alcohol Tweets by a factor of more than 10. The most common themes of pro-drinking Tweets included references to frequent or heavy drinking behaviors and wanting/needing/planning to drink alcohol. The most common sources of pro-alcohol Tweets were organic (i.e., noncommercial).

Conclusions:

Our findings highlight the need for online prevention messages about drinking to counter the strong pro-alcohol presence on Twitter. However, to enhance the impact of anti-drinking messages on Twitter, it may be prudent for such Tweets to be sent by individuals who are widely followed on Twitter and during times when heavy drinking is more likely to occur (i.e., weekends, holidays).

Despite the numerous health and safety consequences that have been identified to be associated with excessive drinking, it continues to be a common activity, especially among youth and young adults (Chen et al., 2013). More than half of young people in the United States (60%) currently believe that heavy episodic drinking (i.e., drinking five or more drinks in one sitting) once or twice per week is not a great risk (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). In 2013, almost a quarter of young people ages 12–20 years in the United States reported drinking alcohol in the past month. Among young people in this same age group, 14% participated in heavy episodic drinking (SAMHSA, 2014). In 2013, the rate of alcohol use disorders was 13% among young adults ages 18–25 (SAMHSA, 2014).

Social influences affect drinking behaviors, and online social networks can influence the spread of drinking behaviors up to three degrees of separation (i.e. friends, and friends of friends) (Bond et al., 2012; Centola, 2010; Christakis & Fowler, 2013; Rosenquist et al., 2010). In a content analysis of 225 college men’s Facebook accounts, most of the profiles (85%) had references to alcohol (Egan & Moreno, 2011). Similarly, a sample of 189 adolescents who were exposed to Facebook profiles portraying alcohol use as normative reported increased pro-alcohol cognitions including greater willingness to drink alcohol and lower perceived vulnerability to the consequences of drinking alcohol (Litt & Stock, 2011). A related study of 18- to 20-year-old undergraduate Facebook users similarly found associations between displays of intoxication/problem drinking references on Facebook profiles and self-reported problem drinking behaviors and drinking-related injuries (Moreno et al., 2012a). These studies and others support increasing recognition that exposure to drinking-related content on social media is common and contributes to the normalization of drinking among young people (Griffiths & Casswell, 2010; Nicholls, 2012).

Twitter is a popular social media platform on which networking about drinking behaviors is likely to occur. Since its founding in 2006, Twitter has become one of the most popular and fastest growing social media networks, with a 44% growth from 2012 to 2013 (Smith & Brenner, 2012; Widrich, 2013). Most Twitter users are young (66% are ages 25 years and younger) (Bennett, 2014; De Cristofaro et al., 2012), and there is less interaction or oversight from older adults/parents compared with that seen on Facebook, where adults between ages 55 and 64 are now the fastest growing demographic (Tappin, 2014). Twitter’s popularity is expected to continue among young people, and a 2013 survey of 8,000 teens found that Twitter was viewed as “the most important social media service” (Edwards, 2013).

However, only two studies have examined Twitter as a social media conduit for networking about drinking behaviors (West et al., 2012; Winpenny et al., 2014). Specifically, West et al. (2012) examined the temporal trends of drinking-related Tweets generated from Twitter users in nine states over 36 days and found that an increase in pro-drinking Tweets occurred during nights and weekends and on New Year’s (West et al., 2012). A related study found that underage youth and young adults in the United Kingdom could easily access pro-alcohol content through Twitter (Winpenny et al., 2014).

In the present study, we sought to build on the limited research on drinking-related Twitter chatter (i.e., conversations, dialogue). By examining the sentiment and themes as well as the source of the Tweets, we hoped to gain a better understanding of what people are socially networking about and who is driving the conversation, as such information could help guide potential interventions. We expected that the bulk of Twitter chatter around alcohol use would be favorable toward drinking. Confirming this anticipated outcome would be especially worrisome because of the largely youthful, presumably underage, presence on Twitter.

Method

The Twitter data in the current study are public. Washington University’s Institutional Review Board reviewed our study protocol, and our research received an institutional review board exemption.

Drinking-related Tweets

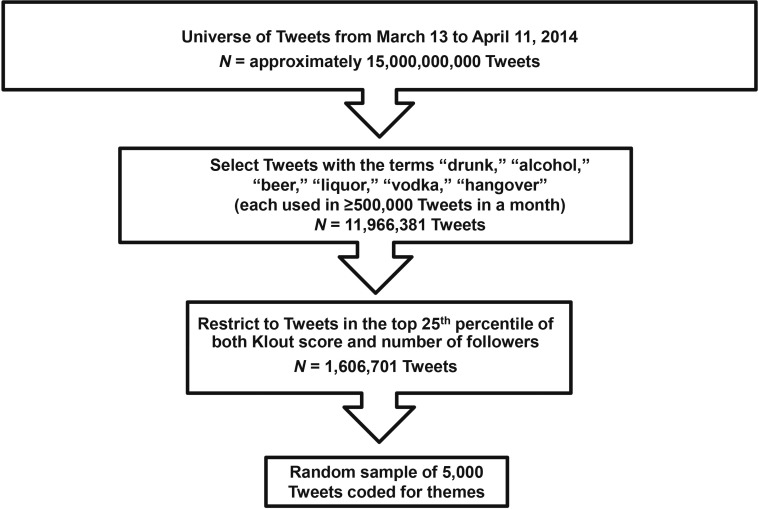

Figure 1 depicts an overview of the methods for collecting and analyzing drinking-related Tweets. Drinking-related Tweets in the English language were collected from March 13 to April 11, 2014, using Simply Measured, a private industry social media analytics company that has access to the Twitter “firehose” (100% of Tweets) via Gnip, a licensed company that can retrieve the full Twitter data stream (Simply Measured, 2013). We compiled an inclusive list of drinking-related terms with input from our research team, web searches, and searching urbandictionary.com, a free online resource that tracks modern slang. Using the free online search engine Topsy.com, we took our initial list of more than 50 drinking-related keywords and determined which keywords were used in an estimated ≥500,000 Tweets per month and did not produce large numbers of irrelevant Tweets. We chose a cutoff of 500,000 Tweets per month to comply with Simply Measured restrictions of staying within a maximum number of total allotted Tweets that we were allowed to collect within a month.

Figure 1.

Collection and analysis of alcohol-related Tweets

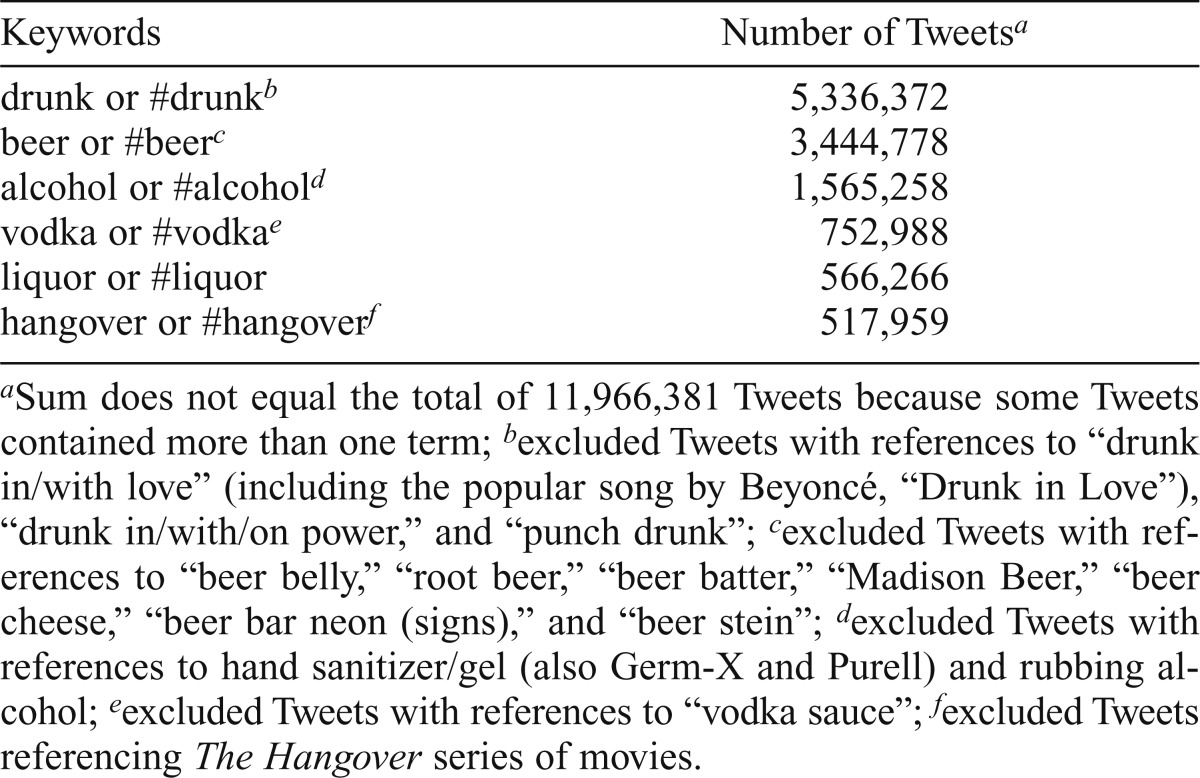

Topsy.com shows the volume of relevant Tweets over the past 30 days as well as many actual Tweets containing the searched keyword. Based on this process, all Tweets including one or more of the following terms were garnered from SimplyMeasured: “drunk” or “#drunk,” “alcohol” or “#alcohol,” “beer” or “#beer,” “liquor” or “#liquor,” “vodka” or “#vodka,” and “hangover” or “#hangover.” Other popular terms such as “wasted” and “drinks” (estimated more than 1 million Tweets per month) were not selected because after we searched these terms on Topsy.com, we found that several of the recent Tweets with these terms did not actually reference alcohol. Examples of some other terms that were considered but did not reach the cutoff of 500,000 Tweets per month included “scotch,” “rum,” “alcoholic,” “booze,” “designated driver,” and “drink and drive.”

Once the Tweets with the final search terms were collected from Simply Measured, we scanned the data, including popular re-Tweets, for phrases that were irrelevant. For example, for the term drunk, we excluded Tweets referencing “drunk in/with love,” “drunk in/with/on power,” and “punch drunk.” For the term alcohol, we excluded Tweets with references to hand sanitizer/gel and rubbing alcohol. For a complete list of exclusions, see footnotes of Table 1.

Table 1.

Drinking-related Tweets by keyword, 03/13/2014–04/11/2014 (N = 11,966,381)

| Keywords | Number of Tweetsa |

| drunk or #drunkb | 5,336,372 |

| beer or #beerc | 3,444,778 |

| alcohol or #alcohold | 1,565,258 |

| vodka or #vodkae | 752,988 |

| liquor or #liquor | 566,266 |

| hangover or #hangoverf | 517,959 |

Sum does not equal the total of 11,966,381 Tweets because some Tweets contained more than one term;

excluded Tweets with references to “drunk in/with love” (including the popular song by Beyoncé, “Drunk in Love”), “drunk in/with/on power,” and “punch drunk”;

excluded Tweets with references to “beer belly,” “root beer,” “beer batter,” “Madison Beer,” “beer cheese,” “beer bar neon (signs),” and “beer stein”;

excluded Tweets with references to hand sanitizer/gel (also Germ-X and Purell) and rubbing alcohol;

excluded Tweets with references to “vodka sauce”;

excluded Tweets referencing The Hangover series of movies.

Tweet sentiment

To examine the sentiment and content of the most influential Tweets, we randomly sampled 5,000 Tweets (that were not direct @replies) from those Tweeters whose handles were in the top 25th percentile for both number of followers and Klout score. We selected handles in the top 25th percentile to be more inclusive of influential handles, as the top 10th percentile would likely have a larger concentration of celebrities or news-focused handles. Klout score considers the extent to which the user’s content is “acted upon” by being clicked, replied to, and/or re-Tweeted (Klout Inc., 2014).

Klout score is used as a measure of influence and is scored on a scale of 0 to 100, where a higher number signifies more influence. This distinguishes Klout score from number of followers, which is a measure of popularity. Tweets that were direct @replies were excluded from qualitative analysis because often the original Tweets would also need to be reviewed to understand the context.

Tweets (along with the content of any links) were coded for sentiment as follows: normalizes or promotes drinking, against or anti-drinking, and neutral/unknown. Tweets that normalized or promoted drinking included those about using or liking alcohol, having a hangover, and implying that drinking is normal or beneficial. This included any type of drinking, not just excessive drinking. Tweets that were against drinking included those discouraging drinking, about disliking alcohol, or suggesting alcohol consumption has bad consequences. We established sentiment codes on a Likert scale: 1 = strongly against drinking, 2 = slightly against drinking, 3 = neutral/unknown, 4 = slightly normalizes/promotes drinking, 5 = strongly normalizes/promotes drinking.

Tweets that could not discernibly be interpreted by the coders as being about alcohol (even if they included a drinking-related term) were excluded from further analysis. For example, the Tweet, “I drunk my sisters redbull…” includes the term drunk but is about drinking an energy drink, not alcohol.

Themes and source of Tweets

In addition to sentiment, the content of Tweets was coded to summarize their main themes and better understand the various drinking-related topics. Two members of the research team with expertise in substance use disorder research scanned 300 random drinking-related Tweets to identify their most common themes, which would then be coded in all of the Tweets. Different sets of themes were distinguished between pro-drinking Tweets versus anti-drinking Tweets. The presence of topics/themes of interest was coded as yes/no.

For pro-drinking Tweets, eight themes were identified and were as follows: (a) Tweeter wants, needs, or plans to drink alcohol, (b) heavy or frequent drinking, (c) Tweeter is drinking/drunk or with a friend/family member who is drinking/drunk, (d) Tweeter was drunk in the recent past or has a hangover, (e) marketing or promotion of alcohol products, bars/restaurants/clubs, alcohol festivals/tastings, etc., (f) Tweet mentions alcohol in relation to sex/romance, (g) Tweet mentions other substances (e.g., tobacco, marijuana, other drugs), and (h) a famous person or song is mentioned/linked to alcohol use.

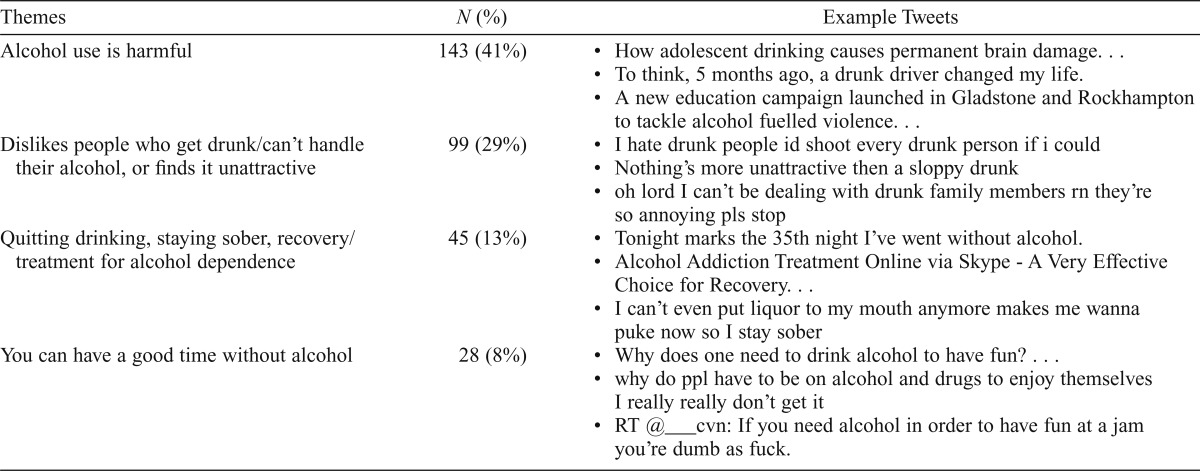

For anti-drinking Tweets, four themes were identified: (a) alcohol use is harmful, (b) quitting drinking, recovery/treatment for alcohol dependence, staying sober, (c) you don’t need alcohol to have a good time, and (d) Tweeter dislikes people who get drunk or can’t handle their alcohol, or finds it unattractive.

The source of the Tweet was coded as a bar or restaurant; other alcohol-focused handle (e.g., has reference to alcohol in the name, such as Drunk Tweets); a health/government organization; the media, celebrity, or an ordinary person; or other type of handle that does not fall into the above categories.

Coding Tweets

We used crowdsourcing to code the Tweets with the crowdsourcing services of CrowdFlower (CrowdFlower, 2013). Crowdsourcing involves using a large network of online (i.e., virtual) workers to complete micro-tasks. Similar to methods used for this study, the methods used by Kim et al. (2013) involved crowdsourcing via CrowdFlower to analyze sentiment of Tweets about U.S. healthcare reform and found a high level of agreement between trained coders from the research team and crowdsourced coders (82.4% for positive sentiment, 100% for negative sentiment).

Members of our research team uploaded the sample of 5,000 Tweets to be analyzed onto the online CrowdFlower platform for CrowdFlower contributors to code (i.e., persons who work on the coding tasks). Instructions about the job, including the codes and example Tweets for the CrowdFlower contributors to study before starting the job, also were uploaded to the CrowdFlower platform. A set of 199 Tweets was coded by two trained members of the research team to be used as test Tweets for the CrowdFlower contributors. Before CrowdFlower contributors could begin coding, they were required to master five test Tweets with predefined answers that were created by the research team.

Test Tweets were also unidentified (i.e., hidden from contributors) and interspersed throughout the full sample of Tweets to ensure that the CrowdFlower contributors responded to tasks truthfully and to a high standard. CrowdFlower assigns a “Trust Score” to contributors, which reflects their accuracy on test questions in the job. CrowdFlower contributors who maintained at least 70% accuracy on test questions were considered “trusted” coders. If contributors’ Trust Scores fell below this preset threshold, they were dropped from the project and all prior codes from those coders were discarded; new coders were assigned in their place.

Each Tweet was coded by at least three CrowdFlower contributors, and the contributors were allowed to code a maximum of 1,000 Tweets. Because Tweets were coded by multiple coders, the numeric values for sentiment coding were first averaged and then collapsed into anti-drinking (values 1.0–2.4), neutral/unknown (values 2.5–3.4), and pro-drinking (3.5–5.0). For the presence of topics/themes of interest (coded as yes/no), the response with the highest confidence score was chosen. Confidence score describes the level of agreement between multiple contributors, is weighted by the contributors’ trust scores, and indicates “confidence” in the validity of the result (https://success.crowdflower.com/hc/en-us/articles/201855939-Get-Results-How-to-Calculate-a-Confidence-Score).

We examined interrater reliability for 200 randomly sampled nontest items. Interrater reliability was good; intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (1,1) for sentiment (i.e., pro-alcohol, neutral, anti-alcohol) was .63. Although the ICC for sentiment was not high, it is arguably good considering the difficulty in interpreting short Tweets that often include slang and/or sarcasm. The percent agreement for the eight pro-drinking themes ranged from 83% to 99% (Mdn = 95%), and Cohen’s κ ranged from .56 to .85 (Mdn = .73). The percent agreement for the four anti-drinking themes ranged from 75% to 100% (Mdn = 92%), and Cohen’s κ ranged from .44 to .80 (Mdn = .75). Last, the percent agreement for the source of the Tweets was 90% (κ = .53).

Results

Drinking-related Tweet volume and temporal trends

A total of 11,966,381 drinking-related Tweets were collected from March 13 to April 11, 2014, using our drinking-related keywords. The most commonly used keyword was “drunk” (5,336,372 Tweets), followed by “beer” (3,444,778 Tweets), and “alcohol” (1,565,258 Tweets). See Table 1 for frequencies of the rest of the drinking-related keywords. In general, Twitter users are sending approximately 500 million Tweets per day, which is about 15 billion Tweets per month; therefore, our results suggest that at least 1 of every 1,250 Tweets being sent on Twitter is about alcohol (note that drinking-related Tweets are actually more common because we did not monitor every drinking-related term). The median number of followers of the Tweets was 309 (interquartile range: 138–672), and the median Klout score was 38.2 (interquartile range: 30.1–43.3).

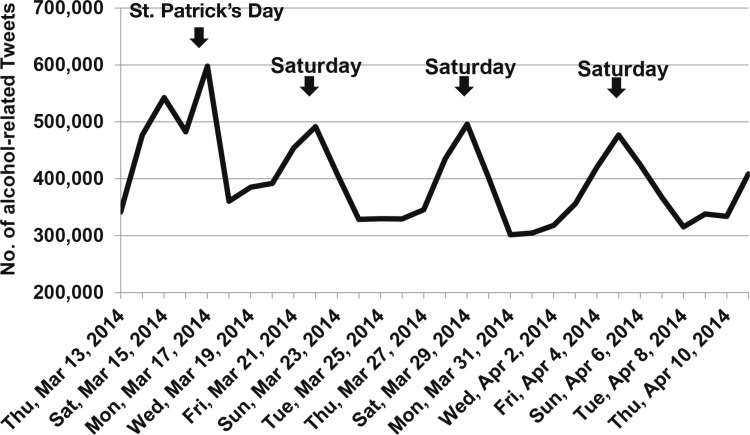

The frequency of drinking-related Tweets over time is shown in Figure 2. There was an increase in drinking-related Tweets on weekends and on St. Patrick’s Day. Some examples of the Tweets that were sent on this holiday were from celebrities, including Lady Gaga: “Happy st Patricks day. Ay the sound of trashed New Yorkers. Grab some green beer and no other instruments. my bf is Irish forgive me.” Lady Gaga has more than 40 million followers, and this specific Tweet was re-Tweeted nearly 8,000 times. In addition, Justin Timberlake, another famous musician and actor, Tweeted, “Happy St. Patrick’s Day!!! Ladies. . . Kiss an Irishman tonight! Or, any guy wearing green! Or, any guy with a beer/drink in his hand. . .” Justin Timberlake has more than 31 million followers, and this specific Tweet was re-Tweeted more than 6,000 times.

Figure 2.

Frequency of drinking-related Tweets over time, March 13–April 11, 2014

Sentiment and reach of alcohol Tweets

We randomly sampled from Tweets that were not direct @replies and were in the top 25th percentile of followers and Klout score (≥ 672 followers and ≥ 43 for Klout score, n = 1,606,701). Among the 5,000 Tweets, 4,800 (96%) were about alcohol. Only 200 Tweets (4%) were not discernibly about alcohol and were excluded from further analysis. Among the 4,800 drinking-related Tweets, 3,813 (79%) were pro-alcohol, 346 (7%) were anti-alcohol, and 641 (13%) had a sentiment that was either neutral or unknown. The potential reach of the pro-alcohol Tweets (sum of the followers of the Tweets: 31,405,125) was approximately eight times higher than the reach of the anti-alcohol Tweets (3,913,088).

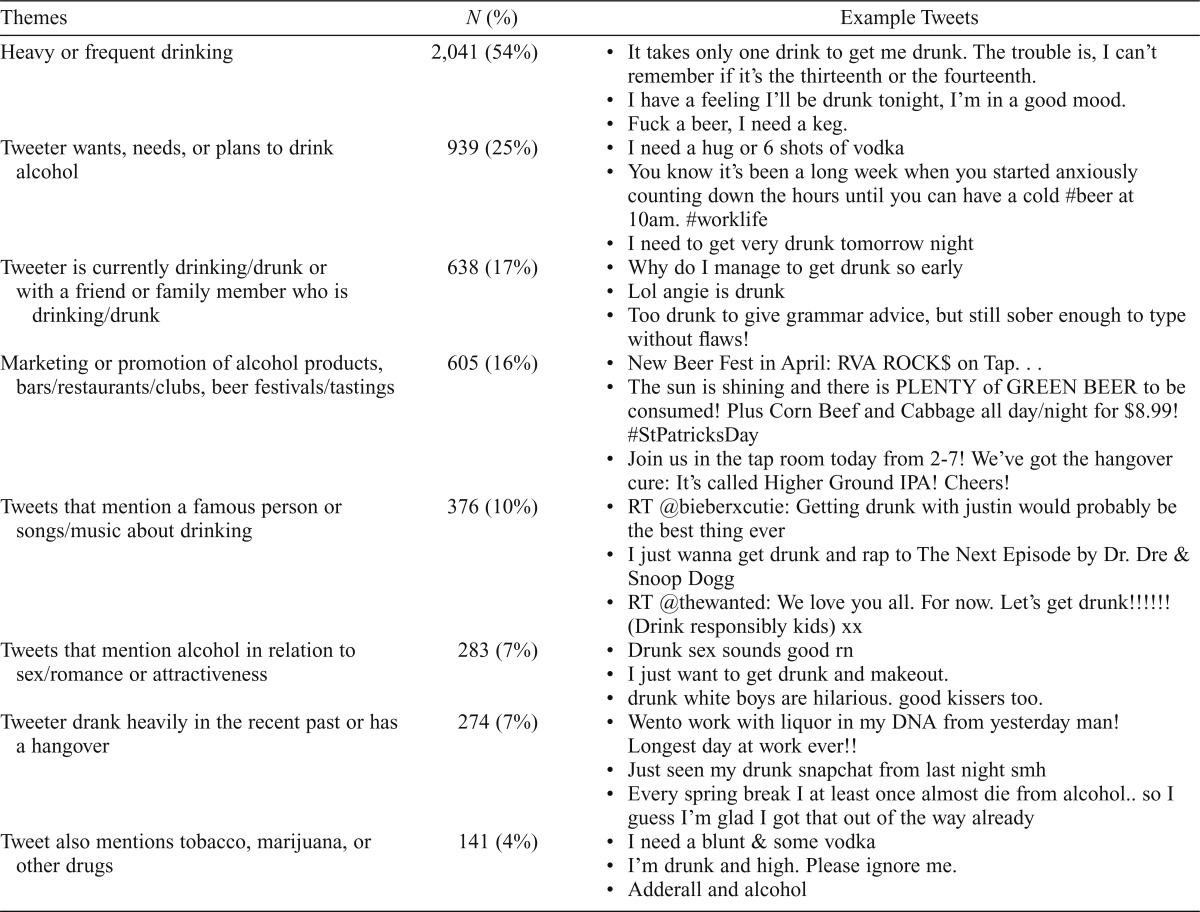

Pro-alcohol Tweets

A little more than half (54%, 2,041/3,813) of the proalcohol Tweets referred to heavy or frequent drinking. Other common themes included wanting, needing, or planning to drink alcohol (n = 939/3,813, 25%); the Tweeter was drinking or drunk or with a friend/family member who was drinking or drunk at the time of the Tweet (n = 638/3,813, 17%); and marketing or promotion of alcohol products, bars, restaurants, clubs, beer festivals, or tastings (n = 605/3,813, 16%). Themes that were present but a little less common included mentioning a famous person or music about drinking (n = 376/3,813, 10%); mentioning sex, romance, or attraction in the context of drinking (n = 283/3,813, 7%); Tweeting about drinking heavily in the recent past or having a hangover (n = 274/3,813, 7%); and mentioning tobacco, marijuana, or other drugs (n = 141/3,813, 4%). Examples of Tweets can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pro-alcohol Tweets (n = 3,813, or 79% of the 4,800 drinking-related Tweets)

| Themes | N (%) | Example Tweets |

| Heavy or frequent drinking | 2,041 (54%) | • It takes only one drink to get me drunk. The trouble is, I can’t remember if it’s the thirteenth or the fourteenth. |

| • I have a feeling I’ll be drunk tonight, I’m in a good mood. | ||

| • Fuck a beer, I need a keg. | ||

| Tweeter wants, needs, or plans to drink alcohol | 939 (25%) | • I need a hug or 6 shots of vodka |

| • You know it’s been a long week when you started anxiously counting down the hours until you can have a cold #beer at 10am. #worklife | ||

| • I need to get very drunk tomorrow night | ||

| Tweeter is currently drinking/drunk or with a friend or family member who is drinking/drunk | 638 (17%) | • Why do I manage to get drunk so early |

| • Lol angie is drunk | ||

| • Too drunk to give grammar advice, but still sober enough to type without flaws! | ||

| Marketing or promotion of alcohol products, bars/restaurants/clubs, beer festivals/tastings | 605 (16%) | • New Beer Fest in April: RVA ROCK$ on Tap… |

| • The sun is shining and there is PLENTY of GREEN BEER to be consumed! Plus Corn Beef and Cabbage all day/night for $8.99! #StPatricksDay | ||

| • Join us in the tap room today from 2–7! We’ve got the hangover cure: It’s called Higher Ground IPA! Cheers! | ||

| Tweets that mention a famous person or songs/music about drinking | 376 (10%) | • RT @bieberxcutie: Getting drunk with justin would probably be the best thing ever |

| • I just wanna get drunk and rap to The Next Episode by Dr. Dre & Snoop Dogg | ||

| •RT @thewanted: We love you all. For now. Let’s get drunk!!!!!! (Drink responsibly kids) xx | ||

| Tweets that mention alcohol in relation to sex/romance or attractiveness | 283 (7%) | • Drunk sex sounds good rn |

| • I just want to get drunk and makeout. | ||

| • drunk white boys are hilarious. good kissers too. | ||

| Tweeter drank heavily in the recent past or has a hangover | 274 (7%) | • Wento work with liquor in my DNA from yesterday man! Longest day at work ever!! |

| • Just seen my drunk snapchat from last night smh | ||

| • Every spring break I at least once almost die from alcohol.. so I guess I’m glad I got that out of the way already | ||

| Tweet also mentions tobacco, marijuana, or other drugs | 141 (4%) | • I need a blunt & some vodka |

| • I’m drunk and high. Please ignore me. | ||

| • Adderall and alcohol |

The most common source of pro-alcohol Tweets appeared to be typical Twitter users/noncelebrities (n = 3,333/3,813, 87%), followed by Tweets from a bar/restaurant, alcohol company/brewer, or alcohol-focused handle (e.g., Live Oak Brewing Co. @LiveOakBrewing, BeerDisciples @Beer_Disciples, My Party Story @DrunkyStory; n = 363/3,813, 10%). Pro-alcohol Tweets that came from a health organization or the media comprised 2% (n = 78/3,813) and from a celebrity, 1% (n = 39/3,813).

Anti-alcohol Tweets

The most common theme among the anti-alcohol Tweets was that alcohol use is harmful (n = 143/346, 41%). Other relatively common themes included disliking people who get drunk/can’t handle their alcohol or finding that getting drunk is unattractive (n = 99/346, 29%); Tweeting about quitting drinking, staying sober, or recovery/treatment for alcohol dependence (n = 45/346, 13%); and that you can still have a good time without alcohol (n = 28/346, 8%). Example Tweets are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Anti-alcohol Tweets (n = 346, or 7% of the 4,800 drinking-related Tweets)

| Themes | N (%) | Example Tweets |

| Alcohol use is harmful | 143 (41%) | • How adolescent drinking causes permanent brain damage… |

| • To think, 5 months ago, a drunk driver changed my life. | ||

| • A new education campaign launched in Gladstone and Rockhampton to tackle alcohol fuelled violence… | ||

| Dislikes people who get drunk/can’t handle their alcohol, or finds it unattractive | 99 (29%) | • I hate drunk people id shoot every drunk person if i could |

| • Nothing’s more unattractive then a sloppy drunk | ||

| • oh lord I can’t be dealing with drunk family members rn they’re so annoying pls stop | ||

| Quitting drinking, staying sober, recovery/treatment for alcohol dependence | 45 (13%) | •Tonight marks the 35th night I’ve went without alcohol. |

| • Alcohol Addiction Treatment Online via Skype - A Very Effective Choice for Recovery… | ||

| • I can’t even put liquor to my mouth anymore makes me wanna puke now so I stay sober | ||

| You can have a good time without alcohol | 28 (8%) | • Why does one need to drink alcohol to have fun?… |

| • why do ppl have to be on alcohol and drugs to enjoy themselves I really really don’t get it | ||

| • RT @__cvn: If you need alcohol in order to have fun at a jam you’re dumb as fuck. |

Among the 346 anti-alcohol Tweets, 281 (81%) appeared to be from a typical Twitter user/noncelebrity, followed by Tweets from a health/government organization/professional or the media (n = 58, 17%). About 2% of the anti-alcohol Tweets came from a bar/restaurant, alcohol company/brewer, alcohol-focused handle, or celebrity.

Neutral or unknown Tweets

The coders identified 641 neutral Tweets (13% of the sample). Nearly one quarter (n = 150, 23%) were considered neutral by coders because they were about news reports that appeared relatively neutral in sentiment (e.g., dispute in Idaho hockey arena over misleading beer prices). About 10% (n = 66) of the Tweets with neutral/unknown sentiment also included those that promoted drinking responsibly, noted the health benefits of drinking in moderation, or mentioned preferring marijuana to alcohol. The rest were considered neutral or unknown because the Tweet was confusing or difficult to discern. The most common source of neutral/unknown Tweets appeared to be typical Twitter users (n = 552, 86%) or the media or a health organization (n = 68, 11%). Neutral alcohol Tweets that came from a bar/restaurant, alcohol company/brewer, alcohol-focused handle, or celebrity comprised approximately 3% of the sample.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the most engaging (i.e., connected with a large audience based on number of followers and Klout score) drinking-related chatter on Twitter over the course of 1 month. Almost 1 in 1,250 of all Tweets sent were about alcohol, and we found nearly 12 million drinking-related Tweets during the 1-month period of analysis (about 400,000 drinking-related Tweets per day). This demonstrates the popularity of drinking-related chatter on Twitter, especially during a time of year in which heavy drinking is popular (spring break and St. Patrick’s Day). Most of the Tweets about alcohol and drinking reflected a positive sentiment toward alcohol use (i.e., normalizing and/or promoting drinking behaviors). In fact, the number of pro-drinking Tweets was more than 10 times the number of anti-drinking Tweets.

Our findings highlight the positive views toward drinking alcohol that are heavily streamed on Twitter in contrast to the Tweets that portray drinking in a negative manner, especially when many young people attend spring break or St. Patrick’s Day activities at bars, clubs, and/or parties where drinking behaviors are encouraged.

We also found that the portrayal of alcohol misuse is a common activity to network about on Twitter. Other predominant themes included that the Tweeter wants, needs, or plans to drink alcohol and that the Tweeter is currently drinking/drunk or with a friend or family member who is drinking/drunk. We cannot determine the extent to which these Tweets correspond with real drinking behaviors, but the Media Practice Model suggests that individuals will use media outlets to disclose actual behaviors or behavioral intent (Brown et al., 1994; Moreno & Whitehill, 2012; Steele, 2005a, 2005b; Steele & Brown, 1995).

In addition, because young people are responsive to peer and media influences, and since the late teens and early 20s are prime ages for hazardous drinking behaviors (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Moreno et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2009c, 2012a, 2012b; Sher et al., 2005; Stone et al., 2012), there is a potential for pro-drinking Tweets to facilitate the modeling of risky drinking behaviors for the receivers of these Tweets. Likewise, Tweets portraying alcohol misuse (e.g., heavy or frequent drinking) as a normal and acceptable behavior could contribute to the normalization of alcohol misuse behaviors.

Our findings indicated a noteworthy presence of commercial alcohol marketing on Twitter, which is in line with existing research that examines how alcohol products are discussed on social media platforms (Mart et al., 2009). However, we found that the bulk of drinking-related Tweets were noncommercial (“organic”) Tweets. In contrast, Huang et al. (2014) found that e-cigarette Tweets were overwhelmingly commercial. Taken together, these findings indicate a distinct contrast between commercial marketing for e-cigarettes and noncommercial posts for alcohol. The fact that drinking-related Tweets are primarily organic is worrisome because the promotion of drinking behaviors, especially when the source is peers, tracks with increased drinking behaviors and intent to drink (Hastings et al., 2005; McCreanor et al., 2013). Similarly, online displays of peer drinking behaviors have been described as a potential type of peer pressure (Moreno et al., 2009b) that can lead to alcohol misuse and potentially enhance one’s popularity when the peers to which individuals feel attached value such behaviors (Balsa et al., 2011; Kobus, 2003).

Many Tweeters who send messages about heavy or frequent drinking may be alike in following the same Twitter handles. For example, certain celebrities (i.e., professional athletes and entertainers) are widely followed on Twitter, and such individuals may be willing to counter the harmful pro-drinking Tweets that are currently being streamed on Twitter. Therefore, those who direct prevention efforts may wish to partner with celebrities who have a mass following of young people on Twitter and enlist their help with spreading “responsible drinking” messages on Twitter. In addition, it is important for prevention messages to be Tweeted strategically during times when heavy drinking is more likely to occur (i.e., weekends, holidays), because these messages may have a greater impact than anti-drinking messages that are streamed without consideration for timing.

Our findings are based on a random sample of drinking-related Tweets sent over the course of 1 month’s time. We realize that this data sample spans the most popular time of year for spring break for both high school and college students. Spring break is notorious for fostering underage drinking. St. Patrick’s Day, also during the period of our data sample, also is known for heavy drinking. Therefore, it is possible that this month would demonstrate an increase in pro-drinking Tweets. Thus, an evaluation of all the drinking-related Tweets streamed over a more extended period (e.g., a year) may yield more comprehensive findings.

Nevertheless, we underscore that the sample of Tweets evaluated in the present study came from the most popular and influential Tweeters, and their Twitter reach is more widespread in comparison with other Tweeters. Our list of drinking-related terms used to acquire Tweets did not include all of the terms that are synonymous with drinking; hence, some drinking-related Tweets were missed. “Wine,” although a popular alcohol term on Twitter (> 500,000 Tweets per month), was not included in the final term list because young people tend to prefer beer or distilled spirits over wine, and we presumed that wine-related Tweets could be qualitatively different from all the other alcohol-related Tweets in our study (Cremeens et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2011).

For instance, in our initial scan of wine-related Tweets, we observed that many of them were promotions about wine tastings or about the use of wine in the context of cooking. Nevertheless, excluding the term wine could bias our results; for example, if we had included “wine,” we might have observed more Tweets about the health benefits of alcohol. Also, we realize that the terms used in this study may lend themselves to more pro-alcohol chatter. Our methodology for selecting terms focused on popularity, based on number of Tweets per month (≥ 500,000 Tweets for each term), in order to capture the most popular drinking-related Twitter chatter. Other keywords/phrases such as “don’t drink and drive,” “DUI,” and “alcoholism” may have shown more anti- or neutral alcohol chatter, but the popularity of these phrases on Twitter is very low in comparison (e.g., the sum of Tweets with these three search terms is < 350,000 Tweets per month).

It is also important to note that some terms (e.g., hangover) could be used in a pro- or anti-alcohol sentiment. In the present study, being “hung over” was considered a normalization of heavy drinking and, therefore, was included in the pro-alcohol grouping. Future studies may explore how Twitter users perceive this type of terminology. It is impossible for us to gauge the extent to which the Tweets correspond with true drinking behaviors; future studies are needed to assess the behavioral fidelity of our findings.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study presents novel and interesting information about the alcohol-related Twitter chatter that disproportionately reflects a positive sentiment toward hazardous drinking behaviors. Our findings are concerning, especially given the potential reach of these messages among young users. These findings are worrisome for normalizing drinking behaviors, especially among young people, and point to the crucial need for prevention efforts to counter these potentially harmful pro-drinking social media messages.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DA039455 (to Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg) and R01DA032843 (to Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg).

References

- Balsa A. I., Homer J. F., French M. T., Norton E. C. Alcohol use and popularity: Social payoffs from conforming to peers’ behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Twitter USA: 48.2 million users now, reaching 20% of population by 2018. 2014, February 27. Retrieved from http://www.medi-abistro.com/alltwitter/twitter-usa-users_b55352. [Google Scholar]

- Bond R. M., Fariss C. J., Jones J. J., Kramer A. D., Marlow C., Settle J. E., Fowler J. H. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature. 2012;489:295–298. doi: 10.1038/nature11421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. D., Dykers C. R., Steele J. R., White A. B. Teenage room culture: Where media and identities intersect. Communication Research. 1994;21:813–827. [Google Scholar]

- Centola D. The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science. 2010;329:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.1185231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. M., Yi H., Faden V. Surveillance Report #96, Trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2011. Bethesda: 2013. MD. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance96/Underage11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Jacobson K. C. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Fowler J. H. Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32:556–577. doi: 10.1002/sim.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremeens J. L., Miller J. W, Nelson D. E., Brewer R. D. Assessment of source and type of alcohol consumed by high school students: Analyses from four states. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2009;3:204–210. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31818fcc2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CrowdFlower . San Franscisco: 2013. Crowdsourcing company. CA. Retrieved from http://www.crowdflower.com. [Google Scholar]

- De Cristofaro E., Soriente C., Tsudik G., Williams A.2012Hummingbird: Privacy at the time of TwitterIn Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP’12) 285–299.Retrieved from http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?reload=true&arnumber=6234419 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. Facebook is no longer the most popular social network for teens. Business Insider. 2013, October 24 Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-and-teen-user-trends-2013-10#ixzz2o9qtomaB. [Google Scholar]

- Egan K. G., Moreno M. A.2011Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ Facebook profiles American Journal of Men’s Health ,5413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R., Casswell S. Intoxigenic digital spaces? Youth, social networking sites and alcohol marketing. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G., Anderson S., Cooke E., Gordon R. Alcohol marketing and young people’s drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2005;26:296–311. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Kornfield R., Szczypka G., Emery S. L. A crosssectional examination of marketing of electronic cigarettes on Twitter. Tobacco Control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii26–iii30. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A., Murphy J., Richards A., Hansen H., Powell R., Haney C. Can Tweets replace polls? A U.S. health-care reform case study. In: Hill C., Dean E., Murphy J., editors. Social media, sociality, and survey research. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Inc Klout. The Klout Score. Retrieved May 6. 2014 2015, from https://klout.com/corp/score.

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction, 98, Supplement 1. 2003:37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt D. M., Stock M. L. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: The roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:708–713. doi: 10.1037/a0024226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mart S., Mergendoller J., Simon M. Alcohol promotion on Facebook. Journal of Global Drug Policy and Practice. 2009;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McCreanor T., Lyons A., Griffin C., Goodwin I., Moewaka Barnes H., Hutton F. Youth drinking cultures, social networking and alcohol marketing: Implications for public health. Critical Public Health. 2013;23:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Briner L. R., Williams A., Walker L., Christakis D. A. Motivations, associations, and consequences: A content analysis of adolescents’ displayed alcohol references on Myspace. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, Supplement. 2009a:S20–S21. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Briner L. R., Williams A., Walker L., Christakis D. A. Real use or “real cool”: Adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on Myspace. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, Supplement. 2009b:S22. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Christakis D. A., Egan K. G., Brockman L. N., Becker T. Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012a;166:157–163. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Grant A., Kacvinsky L., Egan K. G., Fleming M. F. College students’ alcohol displays on Facebook: Intervention considerations. Journal of American College Health. 2012b;60:388–394. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.663841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Parks M. R., Zimmerman F. J., Brito T. E., Christakis D. A. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009c;163:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Whitehill J. M. New media, old risks: Toward an understanding of the relationships between online and offline health behavior. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:868–869. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J. Everyday, everywhere: Alcohol marketing and social media—current trends. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47:486–93. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist J. N., Murabito J., Fowler J. H., Christakis N. A. The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152:426–433. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00007. W141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. J., Grekin E. R., Williams N. A. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. B., Naimi T. S., Cremeens J. L., Nelson D. E. Alcoholic beverage preferences and associated drinking patterns and risk behaviors among high school youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measured Simply.2013Simply Measured, Inc.Seattle, WA. Retrieved fromhttp://simplymeasured.com [Google Scholar]

- Smith A., Brenner J. Twitter use 2012. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/05/31/twitter-use-2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steele J. R. Children, teens, families, and mass media: The millennial generation [Review of the book Children, teens, families, and mass media: The millennial generation, by R. M. Kundanis] Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2005a;82:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Steele J. R. Kids & media in America [Review of the book Kids & media in America, by D. F. Roberts & U. G. Foehr] Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2005b;82:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Steele J. R., Brown J. D. Adolescent room culture: Studying media in the context of everyday life. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Stone A. L., Becker L. G., Huber A. M., Catalano R. F. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:747–775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUHSeries H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville, MD: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tappin S. Facebook vs. Twitter: Who wins the battle for our social attention? 2014, February 6. Retrieved from http://pando.com/2014/02/06/facebook-vs-twitter-who-wins-the-battle-for-our-social-attention. [Google Scholar]

- West J., Hall P., Hanson C., Prier K., Giraud-Carrier C., Neeley E., Barnes M. Temporal variability of problem drinking on Twitter. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Widrich L. Social media in 2013: User demographics for Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest and Instagram. 2013, May 2. Retrieved from https://blog.bufferapp.com/social-media-in-2013-user-demographics-for-twitter-facebook-pinterest-and-instagram. [Google Scholar]

- Winpenny E. M., Marteau T. M., Nolte E. Exposure of children and adolescents to alcohol marketing on social media websites. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49:154–159. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]