Abstract

Summary: Transposable elements constitute a large fraction of vertebrate genomes and, during evolution, may be co-opted for new functions. Exonization of transposable elements inserted within or close to host genes is one possible way to generate new genes, and alternative splicing of the new exons may represent an intermediate step in this process. The genes TMPO and ZNF451 are present in all vertebrate lineages. Although they are not evolutionarily related, mammalian TMPO and ZNF451 do have something in common—they both code for splice isoforms that contain LAP2alpha domains. We found that these LAP2alpha domains have sequence similarity to repetitive sequences in non-mammalian genomes, which are in turn related to the first ORF from a DIRS1-like retrotransposon. This retrotransposon domestication happened separately and resulted in proteins that combine retrotransposon and host protein domains. The alternative splicing of the retrotransposed sequence allowed the production of both the new and the untouched original isoforms, which may have contributed to the success of the colonization process. The LAP2alpha-specific isoform of TMPO (LAP2α) has been co-opted for important roles in the cell, whereas the ZNF451 LAP2alpha isoform is evolving under strong purifying selection but remains uncharacterized.

Contact: mtress@cnio.es or valencia@cnio.es

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Vertebrate genomes, like those of other eukaryotes, are largely constituted by transposable elements (TEs)—up to two-thirds of the human genome according to a recent estimate (de Koning et al., 2011). The evolutionary history of TEs runs parallel to that of the host genome. All life forms are endowed with mechanisms to defend against the threat posed by the activity and expansion of TEs. Despite their threatening character, many TEs have been co-opted for new functions during evolutionary history, in what is considered a form of domestication (Feschotte, 2008; Hoen and Bureau, 2012; Volff, 2006). Some TEs have contributed non-coding regulatory sequences, whereas others have given rise to new protein-coding genes.

Basically, there are two means of co-opting TEs into genes. First, a TE (or part of one) may form a new whole gene. This is probably what occurred with TERT, the telomerase of eukaryotes, which probably originated from the reverse transcriptase (RT) of a non-LTR retrotransposon (Lingner et al., 1997). Alternatively, a TE can insert within or close to a pre-existing gene and combine with it to produce a new protein. This is what happened in the case of the histone methyltransferase SETMAR in the ancestor of primates. Here, a mariner-like DNA transposon inserted downstream of the SET CDS producing an exon that combined with the original exons to form a chimeric protein (SETMAR) with a new DNA-binding domain (Cordaux et al., 2006).

The process of TE exonization has been studied thoroughly (Cordaux and Batzer, 2009; Sela et al., 2010; Sorek, 2007). Many TE-derived exons have been identified in the human genome, the majority are fragments of Alu elements (Deininger, 2011). Most Alu-derived exons are alternatively spliced, presumably because their constitutive expression would be deleterious and is negatively selected (Sorek et al., 2002). It has been proposed that the exonization of TEs would have less deleterious effects if the exons were alternative (Schmitz and Brosius, 2011; Xing and Lee, 2006), because they would not disturb the production of the original isoforms and alternative splicing would allow TEs to coexist in an intermediate stage on the way to full TE co-option.

Most new TE exons appear in 5- or 3-prime UTRs and may play regulatory roles (Sela et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2011). In contrast, TE exonization in protein-coding regions generally produces short, lineage-specific exons that appear as rare splice variants, questioning their biological relevance and suggesting that most probably do not translate into proteins (Gotea and Makałowski, 2006; Lin et al., 2008; Pavlíček et al., 2002; Piriyapongsa et al., 2007).

Here, we investigate the likely TE origins of exons found in both the ZNF451 and TMPO genes. These exons are found in the coding regions of both genes, are alternatively spliced and there is ample evidence of their expression as proteins. The exons are present in mammalian orthologs of ZNF451 and TMPO, whereas they are absent in other vertebrates.

2 Methods

To identify genes with mutually exclusive protein domains, we retrieved human transcripts from Ensembl (Cunningham et al., 2014) that were annotated with CCDS support (Pruitt et al., 2009). We took their Pfam annotations (Finn et al., 2014) and looked for alternative transcripts with different Pfam domains that were mutually exclusively spliced. We identified 40 candidates, of which only nine were retained after manual curation: MOCS2, DST, XIRP2, CUX1, SP100, ZNF655, GNAS, VTN and ZNF451. Proteomics experiments identified peptide support for alternative isoforms for four of these genes (Ezkurdia et al., 2012).

Sequence similarity searches between the LAP2alpha domains (from the TMPO and ZNF451 genes) and vertebrate genome sequences were carried out using TBLASTN, via the Ensembl web server (Cunningham et al., 2014) or locally, in both cases using version 2.2.26 of the BLAST package (Altschul et al., 1997). RPS-TBLASTN profile-based searches (v2.2.29) were performed against the CDD database [version of October 2014 (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2005)]. The Western painted turtle genome [v3.0.1 (Shaffer et al., 2013)] was downloaded from UCSC (Rosenbloom et al., 2014). Repeat annotations for the Chinese soft-shell turtle were obtained from Ensembl, including RepeatMasker (Smit et al., 1996) and RepeatModeler (Smit and Hubley, 2010) predictions. Sequences from genomic regions were extracted with bedtools v2.17.0 (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Multiple sequence alignments were built with Mafft v6.8.57 (Katoh and Standley, 2013), through Jalview v14 (Waterhouse et al., 2009). The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was built with Phyml v3 (Gouy et al., 2010; Guindon et al., 2010) using the best-fit evolutionary model HIVb (Nickle et al., 2007) with gamma-rate heterogeneity and empirical amino acid frequencies (HIVb+G+F), as determined with ProtTest v2.4 (Abascal et al., 2005). Independent multiple sequence alignments were built for the respective LAP2alpha domains of LAP2α and ZNF451-L2a. Overall non-synonymous by synonymous substitution rates were calculated for each of these alignments using the SLAC method (Kosakovsky Pond and Frost, 2005) available in the DataMonkey web server (Delport et al., 2010).

3 Results

3.1 Two genes and an alternatively spliced mammalian-specific protein domain

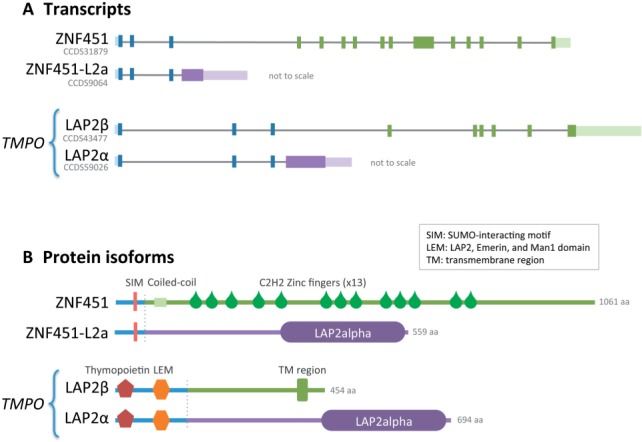

Very few human protein-coding genes generate alternative isoforms in which one Pfam functional domain (Finn et al., 2014) is substituted for another. ZNF451 is one of just nine of these genes. One of the two ZNF451 splice isoforms has a single large 3′-exon with a polyadenylation signal that codes for a C-terminal ‘LAP2alpha’ domain. The incorporation of the polyadenylation signal prevents the incorporation of downstream exons coding for multiple zinc fingers (Fig. 1). The LAP2alpha domain is found in just one other human gene, TMPO. TMPO has a similar pattern of alternative splicing to ZNF451, here the LAP2alpha C-terminal domain replaces a protein region that contains a nuclear attachment trans-membrane (TM) region (Fig. 1). The TMPO LAP2alpha isoform is known as LAP2α, whereas the ZNF451 isoform is referred to as ZNF451-L2a in this work.

Fig. 1.

Schematic organization of the ZNF451 and TMPO transcripts (A) and the domain organization of the translated protein isoforms (B). The presence of a LAP2alpha domain within ZNF451-L2a is supported by an Hmmscan search against Pfam (e value of 1.5e-08). The LAP2alpha domain of both TMPO and ZNF451 is coded by a large 3-prime exon. The exon includes a polyadenylation signal that prevents the simultaneous incorporation of other exons. In the case of ZNF451, alternatively skipped 3-prime exons code for multiple Zinc fingers. In the case of TMPO, they code for the C-terminal half of the protein, which includes a nuclear membrane attachment trans-membrane helix. The exon coding the LAP2alpha domain translates into amino acid regions of 497 and 506 residues (9114 and 2812 bp) in ZNF451 and TMPO, respectively

TMPO (lamina-associated polypeptide 2 gene) codes for several protein isoforms, the most studied of which are LAP2β and LAP2α, with marked differences in their cellular roles (Berger et al., 1996; Dechat et al., 2000). The LAP2β isoform is conserved as far back as vertebrates and can attach to the nuclear envelope through its C-terminal TM region and bind lamin B to the nuclear lamina (Foisner and Gerace, 1993). ZNF451 also evolved along with vertebrates. The main isoform of ZNF451 is a nuclear protein that, upon sumoylation, localizes to promyelocytic leukemia bodies and interacts with the androgen receptor (Feng et al., 2014; Karvonen et al., 2008).

Interestingly, although the genes TMPO and ZNF451 are present in all vertebrate lineages, the isoforms containing the LAP2alpha domain are exclusive to mammals (TMPO) or eutherians (ZNF451). This observation is intriguing and prompted us to determine the origin of the LAP2alpha domain and why it is conserved in mammals.

3.2 The LAP2alpha domain originated from the GAG ORF of a DIRS1-like retrotransposon

To characterize the origin of the LAP2alpha domain, we searched vertebrate genomes using TBLASTN with the amino acid sequences of the LAP2alpha domains of ZNF451-L2a and LAP2α. In placental mammals, we found homology in just TMPO and ZNF451. There was no significant homology within the ZNF451 locus in opossum or platypus, and no significant similarity was found within the TMPO and ZNF451 loci in any non-mammalian vertebrate.

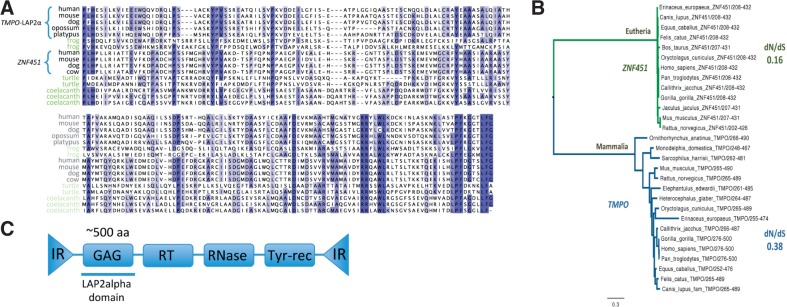

In contrast, we found numerous significant similarity hits (TBLASTN e value < 1e-05) within the genomes of anole lizard (6), Chinese soft-shell turtle (9) and coelacanth (11; Fig 2A). With further sequence searches, we found that these genomes in fact contained hundreds or thousands of copies (TBLASTN hits), revealing the repetitive nature of these sequences and suggesting a TE origin.

Fig. 2.

(A) A multiple sequence alignment including the LAP2alpha domains of mammalian LAP2α and ZNF451-L2a and homologous sequences from non-mammalian DIRS1-like elements. The phylogenetic tree in (B) was built with Phyml for the LAP2alpha domains of LAP2α and ZNF451-L2a. Overall dN/dS ratios were calculated with the SLAC method in DataMonkey (see Supplementary Appendix). (C) A schematic structure of the DIRS1-like element from which the LAP2alpha domain originated

These repetitive sequences are only annotated in Chinese soft-shell turtle [Pelodiscus sinensis (Cunningham et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013)]. Within the turtle, most of the TBLASTN similarity hits overlapped or were very close to repeats annotated as DIRS1-like, suggesting that the LAP2alpha domain may have originated from a DIRS1-like element.

The family of DIRS1 elements has been found in almost all eukaryotes, and species-specific expansions have been reported in anole lizard, Xenopus and zebrafish (Goodwin and Poulter, 2001; Piednoël et al., 2011). DIRS1-like elements are related to LTR-retrotransposons and retroviruses, but they have distinctive features (Cappello et al., 1985)—the presence of inverted terminal repeats (ITRs instead of LTRs) and a specific mechanism for genome integration based on the action of a tyrosine recombinase related to bacteriophage integrases (Goodwin and Poulter, 2001).

To assess the hypothesis of a DIRS1-like origin for the mammalian LAP2alpha domain, we looked for evidence in addition to the repeat annotations from the Chinese soft-shell turtle. We took 792 genomic regions from the Western painted turtle [Chrysemys picta bellii plus (Shaffer et al., 2013)] with homology to the LAP2alpha domain plus 5000 downstream and upstream bps. These regions were scanned with RPS-TBLASTN against the CDD database (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2005). We found sequences coding for RTs, RNases and phage integrases downstream to the regions homologous to LAP2alpha domains, in most cases of the subtype RT_DIRS1 and RNase_HI_RT_DIRS1 (642 and 594 cases, respectively), which are characteristic of DIRS1-like elements. We also identified domains typical of phage-integrases, which are related to the tyrosine recombinase activity of DIRS1-like elements (Goodwin and Poulter, 2001). We manually analyzed some sequences and confirmed the presence of ITRs instead of LTRs, characteristic of DIRS1-like elements (Fig. 2C). Hence, we confirmed that the LAP2alpha domain is related to DIRS1-like elements.

DIRS1-like retrotransposons are composed of two ITRs and four ORFs (Fig. 2C). The first ORF is usually referred to as GAG based on the order of ORFs found in related LTR-retrotransposons and retroviruses, where the GAG ORF codes for proteins of the nucleocapsid. However, no clear homology between ORF1 of DIRS1-like elements and known retroviral GAG proteins has been found (Goodwin and Poulter, 2001). The second ORF codes for an RT, whereas the third and fourth ORFs code for an RNase and a tyrosine-recombinase (Goodwin and Poulter, 2001). We analyzed the relative position of regions similar to RNases, RTs and phage-recombinases with respect to the region found to be homologous to the LAP2alpha domain in the Western painted turtle. Our results indicate that the LAP2alpha domain is homologous to the GAG gene, the first ORF of DIRS-1-like elements.

3.3. Functional implications of the LAP2alpha domain domestication

There is peptide evidence for the expression of both TMPO and ZNF451 LAP2alpha isoforms in mass spectrometry experiments (F. Abascal et al., submitted). Moreover, LAP2α is the alternative splice isoform that has most peptide support.

The TMPO LAP2alpha isoform has important cellular roles in mammals. LAP2α binds lamin A in the nucleoplasm (Dechat et al., 2000; Naetar et al., 2008) and, together with lamin A/C, binds unphosphorylated Rb, tethering it to the nucleus (Markiewicz et al., 2002). This allows Rb to control cell-cycle progression (Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). Interestingly, LAP2α is found within the retroviral pre-integration complex and is necessary for the integration of the Moloney murine leukemia virus (Suzuki et al., 2004), which may reflect the ancestral role of the LAP2alpha domain. A mutation in the LAP2alpha domain can cause dilated cardiomyopathy (Taylor et al., 2005).

The function of the ZNF451-L2a isoform has not been characterized. Because the sumoylation motif falls within the N-terminus that is shared between ZNF451 isoforms, ZNF451-L2a may be also a target of sumoylation. The functional relevance of ZNF451-L2a is supported by the observation that its LAP2alpha domain is evolving under strong purifying selection, even stronger than in LAP2α (overall dN/dS of 0.16 for ZNF451-L2a and 0.38 for LAP2α, see Section 2; Fig. 2B).

4 Conclusions

The evidence presented here strongly supports the possibility that the LAP2alpha domain present in TMPO and ZNF451 has a retrotransposon origin that can be traced back to a DIRS1-like element and the ORF1 (GAG) gene in particular. We have found both direct and indirect supporting evidence for this. Indirect evidence includes (i) LAP2alpha domains are coded by single large exons, a hallmark of retroposition; (ii) although the genes TMPO and ZNF451 are present in other vertebrates, the LAP2alpha domain coding exon is specific to mammals and (iii) in both genes, the mammalian-specific exon is subject to alternative splicing. Direct evidence relies on the very significant sequence similarity between the LAP2alpha domain of both LAP2α and ZNF451-L2a and ORF1 from DIRS1-like retro-TEs.

Many cases of domestication of TEs that have been co-opted for new functions in the cell have been reported (Volff, 2006). In the case presented here, the integration of the DIRS1-like element within pre-existing genes has given rise to chimeric proteins in which the LAP2alpha domain has replaced other protein domains. These new proteins have been maintained throughout the evolution of mammals and are evolving under strong purifying selection, supporting their functional relevance. Probably, the most remarkable feature of this case is that alternative splicing allowed both the new and the original isoforms to coexist. Based on the observation that the same pattern of alternative splicing is found within the ZNF451 and TMPO genes, we infer that the colonizing sequence probably carried an alternative splice acceptor site plus a polyadenylation signal. This could be seen as a neutral colonization that avoided disrupting the original isoforms and making possible the production of new alternative isoforms. This characteristic may have contributed to LAP2alpha’s successful double colonization of two independent genes.

Funding

This work was supported by grants NIH [U41 HG007234] and Spanish MINECO [grant Bio2012-40205].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abascal F., et al. (2005) ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics, 21, 2104–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R., et al. (1996) The characterization and localization of the mouse thymopoietin/lamina-associated polypeptide 2 gene and its alternatively spliced products. Genome Res., 6, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappello J., et al. (1985) Sequence of dictyostelium DIRS-1: an apparent retrotransposon with inverted terminal repeats and an internal circle junction sequence. Cell, 43, 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R., Batzer M.A. (2009) The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet., 10, 691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R., et al. (2006) Birth of a chimeric primate gene by capture of the transposase gene from a mobile element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 8101–8106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham F., et al. (2014) Ensembl 2015. Nucleic Acids Res., 43,D662–D669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning A.P.J., et al. (2011) Repetitive elements may comprise over two-thirds of the human genome. PLoS Genet., 7, e1002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T., et al. (2000) Lamina-associated polypeptide 2alpha binds intranuclear A-type lamins. J. Cell Sci., 113, 3473–3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger P. (2011) Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol., 12, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delport W., et al. (2010) Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics, 26, 2455–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezkurdia I., et al. (2012) Comparative proteomics reveals a significant bias toward alternative protein isoforms with conserved structure and function. Mol. Biol. Evol., 29, 2265–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., et al. (2014) Zinc finger protein 451 is a novel Smad corepressor in transforming growth factor-β signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 289, 2072–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C. (2008) Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nat. Rev. Genet., 9, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R.D., et al. (2014) Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, D222–D230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foisner R., Gerace L. (1993) Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope interact with lamins and chromosomes, and binding is modulated by mitotic phosphorylation. Cell, 73, 1267–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacinti C., Giordano A. (2006) RB and cell cycle progression. Oncogene, 25, 5220–5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin T.J., Poulter R.T. (2001) The DIRS1 group of retrotransposons. Mol. Biol. Evol., 18, 2067–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotea V., Makałowski W. (2006) Do transposable elements really contribute to proteomes? Trends Genet., 22, 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M., et al. (2010) SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol., 27, 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., et al. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol., 59, 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen D.R., Bureau T.E. (2012) Transposable element exaptation in plants. In: Grandbastien,M.A. and Casacuberta,J.M. (eds) Plant Transposable Elements, Berlin Heidelberg, Springer, pp. 219–251. [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen U., et al. (2008) ZNF451 is a novel PML body- and SUMO-associated transcriptional coregulator. J. Mol. Biol., 382, 585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol., 30, 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakovsky Pond S.L., Frost S.D.W. (2005) Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol. Biol. Evol., 22, 1208–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., et al. (2008) Diverse splicing patterns of exonized Alu elements in human tissues. PLoS Genet., 4, e1000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J., et al. (1997) Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science, 276, 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., et al. (2005) CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for protein classification. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, D192–D196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz E., et al. (2002) Lamin A/C binding protein LAP2alpha is required for nuclear anchorage of retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Biol. Cell, 13, 4401–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naetar N., et al. (2008) Loss of nucleoplasmic LAP2alpha-lamin A complexes causes erythroid and epidermal progenitor hyperproliferation. Nat. Cell Biol., 10, 1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickle D.C., et al. (2007) HIV-specific probabilistic models of protein evolution. PLoS One, 2, e503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlíček A., et al. (2002) Transposable elements encoding functional proteins: pitfalls in unprocessed genomic data? FEBS Lett., 523, 252–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piednoël M., et al. (2011) Eukaryote DIRS1-like retrotransposons: an overview. BMC Genomics, 12, 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piriyapongsa J., et al. (2007) Evaluating the protein coding potential of exonized transposable element sequences. Biol. Direct, 2, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K.D., et al. (2009) The consensus coding sequence (CCDS) project: Identifying a common protein-coding gene set for the human and mouse genomes. Genome Res., 19, 1316–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M. (2010) BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics, 26, 841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom K.R., et al. (2014) The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, D764–D770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J., Brosius J. (2011) Exonization of transposed elements: a challenge and opportunity for evolution. Biochimie, 93, 1928–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela N., et al. (2007) Comparative analysis of transposed element insertion within human and mouse genomes reveals Alu’s unique role in shaping the human transcriptome. Genome Biol., 8, R127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela N., et al. (2010) Characteristics of transposable element exonization within human and mouse. PLoS One, 5, e10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer H.B., et al. (2013) The western painted turtle genome, a model for the evolution of extreme physiological adaptations in a slowly evolving lineage. Genome Biol., 14, R28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., et al. (2011) Widespread establishment and regulatory impact of Alu exons in human genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 2837–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.F.A., Hubley R. (2010) RepeatModeler Open-1.0. Repeat Masker Website. [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.F.A., et al. (1996) RepeatMasker Open-3.0. [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R. (2007) The birth of new exons: mechanisms and evolutionary consequences. RNA, 13, 1603–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R., et al. (2002) Alu-containing exons are alternatively spliced. Genome Res., 12, 1060–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., et al. (2004) LAP2alpha and BAF collaborate to organize the Moloney murine leukemia virus preintegration complex. EMBO J., 23, 4670–4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.R.G., et al. (2005) Thymopoietin (lamina-associated polypeptide 2) gene mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat., 26, 566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff J.-N. (2006) Turning junk into gold: domestication of transposable elements and the creation of new genes in eukaryotes. Bioessays, 28, 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., et al. (2013) The draft genomes of soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle yield insights into the development and evolution of the turtle-specific body plan. Nat. Genet., 45, 701–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.M., et al. (2009) Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics, 25, 1189–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Lee C. (2006) Alternative splicing and RNA selection pressure—evolutionary consequences for eukaryotic genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet., 7, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.