Abstract

Motivation: The interpretation of cancer-related single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) considering the protein features they affect, such as known functional sites, protein–protein interfaces, or relation with already annotated mutations, might complement the annotation of genetic variants in the analysis of NGS data. Current tools that annotate mutations fall short on several aspects, including the ability to use protein structure information or the interpretation of mutations in protein complexes.

Results: We present the Structure–PPi system for the comprehensive analysis of coding SNVs based on 3D protein structures of protein complexes. The 3D repository used, Interactome3D, includes experimental and modeled structures for proteins and protein–protein complexes. Structure–PPi annotates SNVs with features extracted from UniProt, InterPro, APPRIS, dbNSFP and COSMIC databases. We illustrate the usefulness of Structure–PPi with the interpretation of 1 027 122 non-synonymous SNVs from COSMIC and the 1000G Project that provides a collection of ∼172 700 SNVs mapped onto the protein 3D structure of 8726 human proteins (43.2% of the 20 214 SwissProt-curated proteins in UniProtKB release 2014_06) and protein–protein interfaces with potential functional implications.

Availability and implementation: Structure–PPi, along with a user manual and examples, isavailable at http://structureppi.bioinfo.cnio.es/Structure, the code for local installations at https://github.com/Rbbt-Workflows

Contact: tpons@cnio.es

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Predicting how single-nucleotide variant (SNV) alters the function of protein products is a topic of growing interest in genomics and bioinformatics (reviewed in Hecht et al., 2013). One of the key limitations of the current computational tools for the prediction of the impact of SNVs is that protein–protein interactions are poorly considered or completely ignored. This is surprising since we know that proteins work as part of protein complexes and interaction networks, and a number of databases with high-quality 3D structurally resolved protein interactome networks are available (Meyer et al., 2013; Mosca et al., 2013), and increasingly used to understand human genetic diseases (Guo et al., 2013; Nishi et al., 2013; Vidal et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Yates and Sternberg, 2013; for a recent review about this topic, see Das et al., 2014). In spite of this, methods that allow a systematic analysis of SNVs, considering known functional residues in spatial contact with the mutation, and including full atom-level description of protein–protein interfaces, are not available.

Indeed, only a few methods, e.g. PMut (Ferrer-Costa et al., 2005), SNPeffect (Reumers et al., 2005), SNPs3D (Yue et al., 2006), PolyPhen-2 (Adzhubei et al., 2010), PoPMuSiC (Dehouck et al., 2011) and MuPIT (Niknafs et al., 2013) use full atom-level description of protein structures explicitly, but they do not include a detailed information about protein–protein interfaces as part of their algorithms (see Supplementary Table S1).

Here, we describe Structure–PPi that precisely analyzes mutations data in their 3D protein complex context. This module represents a significant improvement on existing tools in terms of: (i) ability to map mutations onto 3D structures of protein–protein complexes (experimental and homology-based), (ii) description of functional residues around the SNVs in protein–protein interfaces, additionally Structure–PPi implements a full annotation schema annotating post-translational modification sites, catalytic sites, binding sites residues, Pfam domains and prediction of damaging effects from state-of-the-art methods. Besides, the system selects a single reference sequence for each protein-coding gene (i.e. principal isoform), and provides information about cancer somatic mutations, and their corresponding tumor origin and histology. Since this work was submitted two papers dealing with the analysis of disease mutations at protein-protein interfaces have appeared (Mosca et al., 2015; Porta-Pardo et al., 2015).

2 Implementation and capabilities

2.1 Overview

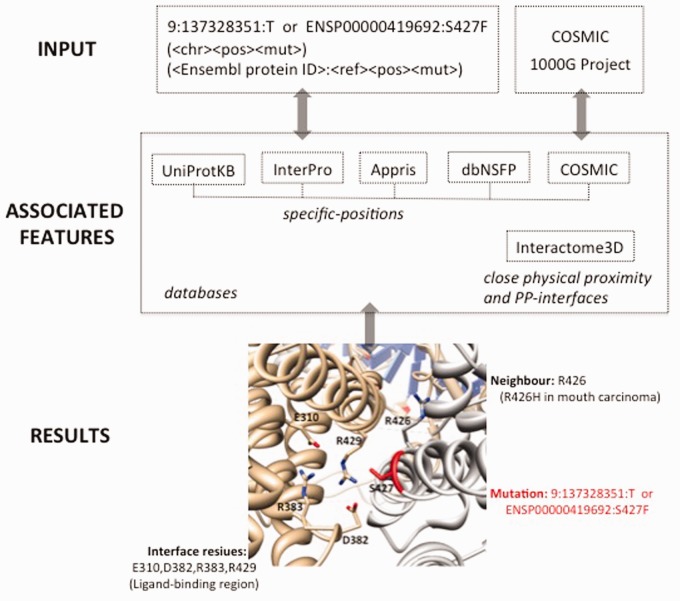

Structure–PPi offers a system to analyze SNV data in their protein 3D structure context. A genomic variant that leads to a substitution in a particular residue of a protein isoform is linked to features associated to that amino acid. Those features include secondary structure, post-translational modification sites, catalytic sites, binding sites residues, Pfam domains, signal peptides, trans-membrane regions, prediction of damaging effects with state-of-the-art methods (i.e. SIFT, Polyphen2, LRT, MutationTaster, MutationAssessor, FATHMM, VEST3, CADD) and somatic mutations extracted from: UniProt (UniProt Consortium, 2013), InterPro (Hunter et al., 2012), APPRIS (Rodriguez et al., 2013), dbNSFP (Liu et al., 2013) and COSMIC (Forbes et al., 2011). Residues in close physical proximity to query SNVs, are extracted from the corresponding 3D structures, including the experimental structures and homology-based models available in the Interactome3D (Mosca et al., 2013) database. The proximity information is used to generate annotations not directly affected by the investigated mutations but that could be disrupted by changes in the close vicinity (defaults 5 Å). Users may submit batches of tens of thousands SNVs to retrieve the available functional annotations for the corresponding SNVs and residues in spatial contact in that protein or the corresponding protein complex (Fig. 1). Figure 1 also shows the study of hotspot position S427 for the ENSP00000419692 protein isoform in bladder cancer. An assessment of Structure–PPi using a validation set (14 pathogenic and 10 neutral) in BRCA1 BRCT domains (Lee et al., 2010) is shown in Supplementary Table S3. Structure–PPi achieves a level of performance similar to that obtained by MetaSVM, a support vector machine algorithm, which incorporate results from state-of-the-art methods (i.e. SIFT, Polyphen2, MutationTaster, Mutation Assessor, FATHMM and LRT) and the maximum frequency observed in the 1000G project (Liu et al., 2013). The results are as follow: MetaSVM (accuracy: 0.83, recall: 1.00, precision: 0.78, MCC: 0.68) and Structure–PPi (accuracy: 0.88, recall: 0.79, precision: 1.00, MCC: 0.78). This assessment reveals that Structure–PPi shows a better precision than MetaSVM, and also a good agreement between predictions and observations. In addition, Supplementary Table S3 shows the utility of Structure–PPi for providing complementary information to the prediction methods. Indeed, this complementary information facilitates discrimination of false-positive results, and also identifies mutations that should be study in more details.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of steps implemented in the Structure-PPi system (see Supplementary Table S2 for more details). The 3D protein complex interface between ENSP00000419692 and human Liver X nuclear receptor beta is also shown (PDB ID: 4nqa)

2.2 Coverage

Structure–PPi maps SNVs onto the protein 3D structure for 8726 human proteins (43.2% of the 20214 SwissProt-curated proteins in UniProtKB release 2014_06). This value of 43.2% is well above the 18% coverage reported by MuPIT (Niknafs et al., 2013).

2.3 Software implementation and requirements

Structure–PPi is an independent component of the Rbbt-framework (“Ruby bioinformatics toolkit” Rbbt; https://github.com/mikisvaz/rbbt; Vázquez et al., 2010). Structure–PPi runs on Unix-based systems (including Linux and Mac). Structure–PPi can be accessed by programmatic access for ruby developers, command-line mode for power users or HTML interface through a web browser (http://structureppi.bioinfo.cnio.es/Structure) for standard users. Structure–PPi includes a pair-wise alignment (Smith–Waterman) step to resolve any potential inconsistency between the isoform sequence and the sequence in the 3D structure, or differences between the isoform sequence and the reference UniProt. Depending on the database used, the throughput on a single process is around hundreds or thousands per second, with less than 500 MB of memory use. We will continue to develop the Structure–PPi, in particular its method for parallelizing file archival and retrieval, and software portability, to further facilitating inclusion into extended genome annotation workflows. We have pre-computed annotations for all coding nsSNVs in COSMIC v69 (∼741 276), and in 1000G Project (∼285 846). The results are available through the website, and some summary statistics and discussion of variants at protein interfaces can be found in Supplementary Table S4. This preliminary analysis might identify disruption of important interactions and improve our understanding about human diseases. Structure–PPi is currently used in different projects, including the ICGC-CLL analysis.

3 Conclusion

We present Structure–PPi, a system to facilitate the comprehensive analysis of cancer-related SNVs, which combines 3D protein structures of protein complexes with functional annotations from different databases. The system implements the generally accepted idea that strong indicators of positive selection for tumorigenesis (driver mutations) are located in functional domain/sites or they affect amino acid residues that have been shown to be important by 3D protein structure. Furthermore, the system provides information about known functional-residues in close physical proximity to query SNVs. Thus, Structure–PPi can provide both mechanistic and biological insights into the role of SNVs in a given cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all members of the Structural Computational Biology group for useful feedback.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the EU's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) project ASSET grant agreement 259348.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Adzhubei I.A., et al. (2010) A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods , 7, 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J., et al. (2014) Exploring mechanisms of human disease through structurally resolved protein interactome networks. Mol. Biosyst. , 10, 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehouck Y., et al. (2011) PoPMuSiC 2.1: a web server for the estimation of protein stability changes upon mutation and sequence optimality. BMC Bioinformatics , 12, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Costa C., et al. (2005) PMUT: a web-based tool for the annotation of pathological mutations on proteins. Bioinformatics , 21, 3176–3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S.A., et al. (2011) COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res., 39, D945–D950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., et al. (2013) Dissecting disease inheritance modes in a three-dimensional protein network challenges the “Guilt-by-Association” principle. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 93, 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht M., et al. (2013) News from the protein mutability landscape. J. Mol. Biol., 425, 3937–3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S., et al. (2012) InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, D306–D312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.S., et al. (2010) Comprehensive analysis of missense variations in the BRCT domain of BRCA1 by structural and functional assays. Cancer Res., 70, 4880–4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., et al. (2013) dbNSFP v2.0: a database of human non-synonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum. Mutat. , 34,E2393–E2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M.J., et al. (2013) INstruct: a database of high-quality 3D structurally resolved protein interactome networks. Bioinformatics, 29,1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca R., et al. (2013) Interactome3D: adding structural details to protein networks. Nat. Methods , 10, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca R., et al. (2015) dSysMap: exploring the edgetic role of disease mutations. Nat. Methods, 12, 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niknafs N., et al. (2013) MuPIT interactive: webserver for mapping variant positions to annotated, interactive 3D structures. Hum. Genet., 132,1235–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi H., et al. (2013) Cancer missence mutations alter binding properties of proteins and their interaction networks. PLoS ONE , 8, e66273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta-Pardo E., et al. (2015) Cancer3D: understanding cancer mutations through protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res., 43, D968–D973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reumers J., et al. (2005) SNPeffect: a database mapping molecular phenotypic effects of human non-synonymous coding SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. , 33,D527–D532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J.M., et al. (2013) APPRIS: annotation of principal and alternative splice isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D110–D117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium. (2013) Update on activities at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. , 41, 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez M., et al. (2010) Rbbt: a framework for fast bioinformatics development with ruby. Adv. Intell. Soft Comput., 74, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal M., et al. (2011) Interactome networks and human disease. Cell, 144,986–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., et al. (2012) Three-dimensional reconstruction of protein networks provides insight into human genetic disease. Nat. Biotechnol. , 30,159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P., et al. (2006) SNPs3D: candidate gene and SNP selection for association studies. BMC Bioinf., 7, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates C.M., Sternberg M.J. (2013) The effects of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) on protein–protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol., 425, 3949–3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.