Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular diseases are the current leading causes of death and disability globally.

Objective

To assess the effects of a basic educational program for cardiovascular prevention in an unselected outpatient population.

Methods

All participants received an educational program to change to a healthy lifestyle. Assessments were conducted at study enrollment and during follow-up. Symptoms, habits, ATP III parameters for metabolic syndrome, and American Heart Association’s 2020 parameters of cardiovascular health were assessed.

Results

A total of 15,073 participants aged ≥ 18 years entered the study. Data analysis was conducted in 3,009 patients who completed a second assessment. An improvement in weight (from 76.6 ± 15.3 to 76.4 ± 15.3 kg, p = 0.002), dyspnea on exertion NYHA grade II (from 23.4% to 21.0%) and grade III (from 15.8% to 14.0%) and a decrease in the proportion of current active smokers (from 3.6% to 2.9%, p = 0.002) could be documented. The proportion of patients with levels of triglycerides > 150 mg/dL (from 46.3% to 42.4%, p < 0.001) and LDL cholesterol > 100 mg/dL (from 69.3% to 65.5%, p < 0.001) improved. A ≥ 20% improvement of AHA 2020 metrics at the level graded as poor was found for smoking (-21.1%), diet (-29.8%), and cholesterol level (-23.6%). A large dropout as a surrogate indicator for low patient adherence was documented throughout the first 5 visits, 80% between the first and second assessments, 55.6% between the second and third assessments, 43.6% between the third and fourth assessments, and 38% between the fourth and fifth assessments.

Conclusion

A simple, basic educational program may improve symptoms and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, but shows low patient adherence.

Keywords: Health Behavior, Life Style, Prevention, Obesity, Risk Factors, Health Education

Introduction

According to estimations of the World Health Organization, cardiovascular diseases are the current leading causes of death and disability globally, with an increasing tendency and negative projection for 2030. Although a large proportion is preventable, their incidence continues to increase mainly because preventive measures are inadequate1.

Several trials have reported the effects of lifestyle intervention programs on high-risk populations. Some have shown a significant decrease in the incidence of diabetes in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance2. Others have reported the beneficial effects of lifestyle modification on blood pressure control3. Lifestyle interventions seem to be at least as effective as drugs4. Therefore, lifestyle modification, long considered the cornerstone of interventions, is extremely important to reduce the burden of chronic diseases1.

In the light of this epidemic scenario, government health policies in industrialized countries are focusing on programs to modify cardiovascular risk factors5. Smoking bans to protect citizens from the effects of second-hand smoke have been successfully implemented in many countries, showing positive effects even in this short period of time6,7. However, achievements considering other modifiable risk factors remain discouraging8. Furthermore, comprehensive and complex educational programs lack a widespread implementation in the general population, and are related to lesser patient compliance9-11. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the practicability of a basic educational program to turn established behaviors into a healthy lifestyle in an urban outpatient population, as well as to define the effects of these changes on symptoms and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods

Design and study population

The AsuRiesgo (acronym from Asuncion modificacion de factores de Riesgo cardiovascular) study is a case series type prospective trial, in which all participants received the same intervention - an educational program to increase awareness on cardiovascular risk factors, and, based on this, to change usual habits into a healthy lifestyle. The cohort included an unselected outpatient population aged ≥ 18 years old attending a high-output tertiary clinic in an urban setting in Asuncion, Paraguay.

Patients in all waiting areas of the hospital were invited to participate. All assessments were conducted at study enrollment and at every visit during follow-up. Participants were asked to attend follow-up examinations every 6 months. The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol and all patients provided written informed consent. This study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov under the identifier: NCT00486993.

Assessment of symptoms and habits

Personal and family information was obtained. Exertional dyspnea and chest pain were graded according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) classification, respectively. History of known coronary artery disease and/or diabetes mellitus was documented.

Prevalence of parameters of cardiovascular health metrics, as defined by the American Heart Association's (AHA) 2020 Strategic Impact Goals Committee was assessed, and ideal, intermediate or poor levels were calculated5. Relative change after education to a healthy lifestyle was estimated for each of the 4 health behaviors (smoking, diet, physical activity and body mass) and 3 health factors (plasma glucose, cholesterol levels and blood pressure).

Smoking habit was extensively interrogated. However, only the aspects defined by the American Heart Association's 2020 Strategic Impact Goals Committee5 were considered for analysis. Current smokers were classified as being in the group with a poor level of cardiovascular health; those who quit smoking < 12 months, as intermediate; and non-smokers as well as those who quit smoking ≥ 12 months, as ideal.

Dietary behavior was defined qualitatively according to the daily intake of three groups of foods: meats/animal fats, vegetables/fruits and sugar/carbohydrates. The degree of consumption was assessed for each group as "none", "low", "moderate" or "high". A simple healthy diet score was built accordingly, and scores from 1-3 points were considered as "poor", from 4-6 points as "intermediate", and from 7-9 points as "ideal".

The level of daily physical activity was classified as sedentary behavior, when not even a short recreational-type walk was achieved; moderate, when at least 30 minutes of a recreational-type walk at moderate intensity was achieved daily; and important, when ≥ 30 minutes of vigorous recreational walk or sports were achieved. Participants were classified as having a poor, intermediate or ideal level, correspondingly.

The daily level of psychological stress was classified subjectively as mild or absent, moderate or important.

Assessment of anthropometric and laboratory parameters

All parameters were assessed at inclusion and at every follow-up visit. Body weight, height, body mass index (BMI), abdominal circumference and blood pressure, as well as standard laboratory parameters including triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol and fasting plasma glucose were assessed as described in another report12. In addition, the prevalence of AHA parameters of cardiovascular health metrics was assessed5.

Education to a healthy lifestyle

All participants attended one educational workshop at the beginning, and were encouraged to participate in similar workshops at every visit during follow-up. Informative material was compiled from recommendations published in another report13.

Basic knowledge on cardiovascular diseases and risk factors was addressed. Targets were directed to quit smoking, switching to a healthy diet, avoiding sedentary lifestyle and working on reducing daily psychological stress. The following strategies were undertaken to reach these goals: 1) tips on how to quit smoking; 2) aspects concerning a healthy diet, with suggestions for everyday life; 3) suggestions on how to implement a daily physical exercise program; and 4) useful strategies for reducing daily psychological stress.

Smoking cessation: patients were advised of the value of stopping and the risks to health of continuing smoking. It was suggested to set a date to stop and stop completely on that day, to review experiences concerning measures that helped or that hindered, and to ask family members and friends for their support. No nicotine replacement drugs were used12.

Healthy diet: patients were asked to eat moderately; to reduce consumption of meats, especially red meats; to avoid consumption of animal fats and hydrogenated vegetable oils; to switch to daily meals with emphasis on vegetables and fruits; to reduce daily salt intake; and to reduce consumption of sugar and refined wheat products, switching to whole-wheat products instead.

Physical activity: patients given suggestions to avoid a sedentary lifestyle by accomplishing at least a 30-minute recreational daily walk. They were motivated to start at a moderate pace, and to increase speed progressively to a level as vigorous as possible. Furthermore, they were stimulated to practice aerobic sports according to their possibilities13.

Psychological stress: physicians in charge of the study addressed coping with daily psychological stress. Possible causes such as occupational, familial and/or social were examined and helpful measures were suggested. A professional psychological support was provided as required.

Workshops were conducted by physicians and nurses trained for this purpose. A close supervision and coaching was done by physicians in charge of this study. Treatment was further managed by the corresponding referring physician. No change in medications was made as part of the study. Patients were merely told to follow strictly the indications of their treating physician. Further written material, as well as current information related to the study were posted on the website: http://asuriesgo.de.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with the use of SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SD). Frequencies and percentages are used to describe categorical variables. To test for differences between the baseline and the second assessment, paired t-tests for continuous data and the McNemar's test or the Bowker's test for categorical data were applied. No adjustments for multiple testing were performed, since this was an exploratory data analysis. Patient dropout as a surrogate indicator for adherence was examined throughout the first 5 visits. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The recruitment of patients was conducted in a continuous manner between May, 2006 and May, 2012. Approximately 40,000 individuals were invited to participate in this period. A total of 15,073 patients gave written informed consent and entered the study.

Baseline characteristics of the patient population

Anthropometric characteristics, personal and familial disease history and symptoms are presented in Table 1. Female prevalence in this population was high - more than double that of males.

Table 1.

Baseline of the study population

| Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | 15,073 | |

| Age, yrs | 50.8 ± 15.1 | |

| Women, n (%) | 10,377 (69) | |

| Weight, kg | 77.3 ± 16.0 | |

| Body mass index, n (%) | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 2,966 (19.7) | |

| 25-29 kg/m2 | 5,583 (37.0) | |

| > 30 kg/m2 | 6,524 (43.3) | |

| Personal history of CAD, n (%) | 390 (2.6) | |

| Known diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2,063 (13.7) | |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 819 (5.4) | |

| Symptoms | ||

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 5,221 (34.7) | |

| NYHA I | 527 (3.5) | |

| NYHA II | 2,743 (18.2) | |

| NYHA III | 1,951 (12.9) | |

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 2,388 (15.8) | |

| CCS I | 407 (2.7) | |

| CCS II | 1,271 (8.4) | |

| CCS III | 710 (4.7) | |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Data for categorical variables are shown as the number of cases with percentages in brackets. CAD: coronary artery disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association functional classification; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina classification. Numbers of missing values smaller than or equal to ten are not reported.

The prevalence of known coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus was low, and family history of coronary heart disease was present in 5.4% of the study population. Patients stated having shortness of breath on exertion, with a NYHA functional classification grade II in approximately 18% and NYHA grade III in approximately 13% of patients. The prevalence of angina pectoris on exertion was lower, with approximately 8% of patients being classified as CCS II and 5% as CCS III.

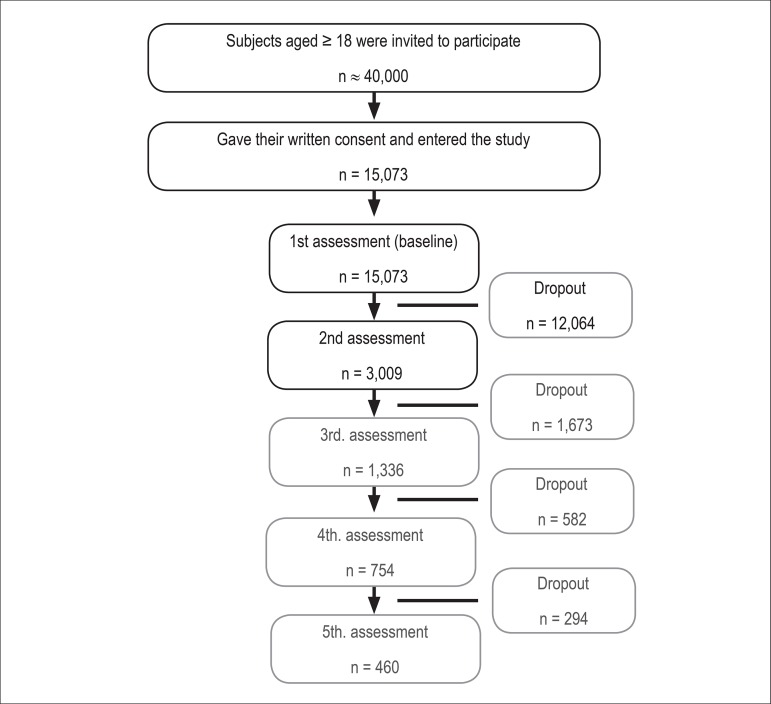

Dropout of participants during follow-up

Patients were requested to attend a follow-up visit by telephone or Short-Message-Service (SMS) if they did not come spontaneously to the visit scheduled for 6 months after the first assessment. However, although striving efforts were undertaken, a large dropout rate could be documented throughout the first 5 visits, 80% between the first and second assessments, 55.6% between the second and third, 43.6% between the third and fourth, and 38% between the fourth and fifth assessments. The median time span between the first and second assessments was 10 months (25th, 75th percentiles, 7 to 21 months). Patient flow and dropout rate during follow-up throughout the first five assessments were documented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants during the study. Only the first 5 visits considered for dropout analysis are shown here. Changes in parameters were analyzed between the first and second assessments.

Change in parameters after education to a healthy lifestyle

Comparative analysis between the first and second assessments was carried out in patients for whom the information on medical history and habits, physical examination and laboratory tests had been assessed at both visits (n = 3,009).

Anthropometrics, symptoms and habits

A slight but significant decrease in weight (from 76.6 ± 15.3 kg to 76.4 ± 15.3 kg, p = 0.002) and body mass index (from 30.2 ± 5.6 kg/m² to 30.1 ± 5.6 kg/m², p=0.004) could be documented at the second assessment after education to a healthy lifestyle (Table 2). The proportion of patients with dyspnea on exertion NYHA grade II and grade III was also lower at the second visit (from 23.4% to 21.0%, and from 15.8% to 14.0%, respectively). The proportion of patients with angina pectoris on exertion decreased as well, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Changes in parameters at the second assessment after education to a healthy lifestyle (n = 3,009)

| Variable | Baseline | Second Assessment | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 76.6 ± 15.3 | 76.4 ± 15.3 | 0.002 * | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.2 ± 5.6 | 30.1 ± 5.6 | 0.004 * | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Dyspnea, n (%) | |||||

| No | 1,699 (56.6) | 1,843 (61.3) | |||

| Yes | 1,310 (43.5) | 1,164 (38.7) | < 0.001 † | ||

| NYHA I | 131 (4.4) | 111 (3.7) | |||

| NYHA II | 705 (23.4) | 632 (21.0) | |||

| NYHA III | 474 (15.8) | 421 (14.0) | |||

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2,547 (84.6) | 2,580 (85.8) | |||

| Yes | 462 (15.4) | 428 (14.2) | 0.143 † | ||

| CCS I | 77 (2.6) | 69 (2.3) | |||

| CCS II | 231 (7.7) | 224 (7.4) | |||

| CCS III | 154 (5.1) | 135 (4.5) | |||

| Smoking, n (%) | |||||

| Current smoker | |||||

| No | 2,110 (70.1) | 2,129 (70.8) | |||

| Yes | 899 (29.9) | 880 (29.2) | 0.110 † | ||

| Active | |||||

| No | 2,900 (96.4) | 2,923 (97.1) | |||

| Yes | 109 (3.6) | 86 (2.9) | 0.002 † | ||

| Passive | |||||

| No | 2,196 (73.0) | 2,199 (73.1) | |||

| Yes | 813 (27.0) | 810 (26.9) | 0.772 † | ||

| Former smoker | |||||

| No | 2,343 (77.9) | 2,309 (76.7) | |||

| Yes | 666 (22.1) | 700 (23.3) | < 0.001 † | ||

| Diet, n (%) | |||||

| Poor | 983 (32.7) | 690 (22.9) | < 0.001 ‡ | ||

| Intermediate | 1,785 (59.3) | 1,901 (63.2) | |||

| Ideal | 241 (8.0) | 417 (13.9) | |||

| Physical activity, n (%) | |||||

| No | 1,626 (54.0) | 1,478 (49.2) | < 0.001 ‡ | ||

| Some | 1,378 (45.8) | 1,519 (50.5) | |||

| Frequent | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | |||

| Psychological stress level, n (%) | |||||

| Mild or absent | 604 (42.1) | 453 (46.5) | 0.006 ‡ | ||

| Moderate | 646 (45.0) | 391 (40.1) | |||

| Important | 185 (12.9) | 131 (13.4) | |||

| Missing | 1,574 | 2,034 | |||

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Data for categorical variables are shown as the number of cases with percentages in brackets. NYHA: New York Heart Association functional classification; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina classification. Changes in dietary intake are depicted on Table 4. P values were calculated using the t test *, the McNemar's test † for symmetry and the Bowker's test ‡ for symmetry, as required. Numbers of missing values smaller than four are not reported.

The proportion of current active smokers decreased (from 3.6% to 2.9%, p = 0.002). There were also fewer passive smokers, but the difference here was not statistically significant. The proportion of former smokers increased correspondingly (from 22.2% to 23.3%). The proportion of patients with a sedentary lifestyle decreased (from 54.0% to 49.2%), while an increase in daily physical activities could be documented correspondingly (from 45.8% to 50.5%). Although the level of psychological stress in patients who described it as "important" increased slightly after education to a healthy lifestyle (from 12.9% to 13.4%); the level of stress improved in the group of patients with "mild or absent" (from 42.1% to 46.5%) and with "moderate" intensity (from 45.0% to 40.1%).

ATP III criteria for metabolic syndrome and LDL cholesterol

The proportion of patients with any particular parameters for metabolic syndrome showed minimal, but statistically not significant differences at the second assessment (Table 3; for brevity, subgroups are not shown). However, significant improvement in lipid profiles could be documented, with a decrease in the proportion of patients with triglycerides > 150 mg/dL (from 46.3% to 42.4%, p < 0.001), especially in patients ≥ 60 years old. Additionally, a mild improvement in HDL-cholesterol levels could be observed in men, with a significant decrease in the prevalence of HDL < 40 mg/dL in the age group between 40 and 49 years of age (from 29.7% to 20.4%, p = 0.009). Tendency to a lower prevalence of low HDL levels was found only in the group of female patients between 60 and 69 years of age (from 46.5% to 43.4%, p = 0.084).

Table 3.

Changes in the prevalence of ATP III parameters for metabolic syndrome and LDL cholesterol in participants at the second assessment after education for a healthy lifestyle (n = 3,009)

| Variable | Baseline | Second Assessment | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference | |||||

| Women > 88 cm, n (%) | 1,824 (79.6) | 1,827 (79.7) | 0.845 | ||

| Men > 102 cm, n (%) | 302 (42.1) | 299 (41.7) | 0.763 | ||

| Triglycerides > 150 mg/dL, n (%) | 1,382 (46.3) | 1,268 (42.4) | < 0.001 | ||

| Missing | 26 | 21 | |||

| HDL cholesterol | |||||

| Women < 50 mg/dL, n (%) | 978 (43.6) | 1,018 (45.2) | 0.250 | ||

| Missing | 50 | 38 | |||

| Men < 40 mg/dL, n (%) | 187 (26.7) | 175 (24.9) | 0.280 | ||

| Missing | 16 | 15 | |||

| Blood pressure | |||||

| Systolic > 130 mmHg, n (%) | 1,352 (44.9) | 1,318 (43.8) | 0.279 | ||

| Diastolic > 85 mmHg, n (%) | 941 (31.3) | 913 (30.3) | 0.362 | ||

| Fasting glucose > 100mg/dL, n (%) | 591 (19.8) | 603 (20.2) | 0.492 | ||

| Missing | 23 | 24 | |||

| LDL cholesterol > 100 mg/dL, n (%) | 2,039 (69.3) | 1,937 (65.5) | < 0.001 | ||

| Missing | 66 | 53 | |||

Data are presented as the number of cases with percentages in brackets. ATP III: Adult Treatment Panel III (Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults), HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein. P values were calculated using the McNemar's test for symmetry. Numbers of missing values smaller than four are not reported.

Improvement was also found in LDL-cholesterol levels > 100 mg/dL (from 69.3% to 65.5%, p < 0.001). This decrease was statistically significant in the age groups between 50-59 years of age (p = 0.03) and 60-69 years of age (p = 0.004).

AHA parameters of cardiovascular health metrics

Changes in the prevalence of parameters of cardiovascular health metrics, as defined by the American Heart Association's 2020 Strategic Impact Goals Committee5 after education to a healthy lifestyle are depicted in Table 4. Relative improvement in parameters of cardiovascular health are presented as percentage of change for each of the 4 health behaviors (smoking, diet, physical activity, body mass) and 3 health factors (plasma glucose, cholesterol levels, blood pressure).

Table 4.

Changes in prevalence of parameters of AHA 2020 cardiovascular health metrics after education for a healthy lifestyle (n = 3,009)

| Variable | Baseline | Second Assessment | % Change | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | |||||

| Poor | 109 (3.6) | 86 (2.9) | -21.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 32 (1.1) | 28 (0.9) | -12.5 | ||

| Ideal | 2,868 (95.3) | 2,893 (96.2) | 0.9 | ||

| Diet | |||||

| Poor | 983 (32.7) | 690 (22.9) | -29.8 | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 1,785 (59.3) | 1,901 (63.2) | 6.5 | ||

| Ideal | 241 (8.0) | 417 (13.9) | 73.0 | ||

| Physical activity | |||||

| Poor | 1,626 (54.0) | 1,478 (49.2) | -9.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 1,378 (45.8) | 1,519 (50.5) | 10.2 | ||

| Ideal | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | 80.0 | ||

| Body weight | |||||

| Poor | 1,376 (45.7) | 1,356 (45.1) | -1.5 | 0.323 | |

| Intermediate | 1,166 (38.8) | 1,171 (38.9) | 0.4 | ||

| Ideal | 467 (15.5) | 481 (16.0) | 3.0 | ||

| Glucose | |||||

| Poor | 317 (10.6) | 303 (10.2) | -4.4 | 0.046 | |

| Intermediate | 704 (23.6) | 745 (25.0) | 5.8 | ||

| Ideal | 1,965 (65.8) | 1,937 (64.9) | -1.4 | ||

| Missing | 23 | 24 | |||

| Cholesterol | |||||

| Poor | 674 (22.6) | 515 (17.2) | -23.6 | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 935 (31.3) | 900 (30.1) | -3.7 | ||

| Ideal | 1,377 (46.1) | 1,574 (52.7) | 14.3 | ||

| Missing | 23 | 20 | |||

| Blood pressure | |||||

| Poor | 1,187 (39.4) | 1,131 (37.6) | -4.7 | 0.348 | |

| Intermediate | 1,185 (39.4) | 1,233 (41.0) | 4.1 | ||

| Ideal | 637 (21.2) | 645 (21.4) | 1.3 | ||

Data are presented as the number of participants with percentages in brackets. P values were calculated using the Bowker's test for symmetry. AHA 2020: American Heart Association's 2020 Strategic Impact Goals.

Significant improvement in some parameters were documented. A ≥ 20% improvement was found at the level graded as poor for smoking (-21.1%), diet (-29.8%), and cholesterol level (-23.6%). Minor changes at the same level were also observed for physical activity (-9.1%), body weight (-1.5%), plasma glucose (-4.4%), and blood pressure (-4.7%). Improvements were also found at the level grade as ideal, especially considering healthy diet (+73%) and cholesterol levels <200 mg/dL (+14.3%).

Discussion

In this prospective study, we could show that a simple basic educational program may improve symptoms and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in an unselected outpatient population. An improvement in weight and dyspnea on exertion, as well as a decrease in the proportion of current active smokers were documented. The proportion of patients with high levels of triglycerides and LDL cholesterol improved. In addition, a ≥ 20% improvement of the American Health Association 2020 metrics was found for smoking, diet and cholesterol level. However, the low adherence, as evidenced by a high dropout rate of participants throughout the study follow-up, was documented.

Only minimal changes in weight (mean weight loss of 0.2 kg) and no significant changes in abdominal circumference were found in this study, conducted in a non-coached approach. Similar changes could be observed in prospective studies when patients were included in study arms in which the intervention consisted only in consultations with a dietitian and the use of self-help resources14,15. However, patients included in intervention arms with an intensive, coached program toward weight reduction, delivered in a weekly basis, showed a much higher decrease in body weight (mean weight loss of 4 kg)14,15. Changes in diet and sedentary life habits in the last decades have led to a significant decline in the global health profiles of the population. Specific dietary and lifestyle factors have been shown to be independently associated with long-term weight gain, including changes in the consumption of specific foods and beverages, reduced physical activity, alcohol consuption, television watching, and smoking16. Moreover, diet quality in patients with known vascular disease or diabetes mellitus has a strong association with cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes. A higher-quality diet was associated with a lower risk of recurrent CVD events among people ≥ 55 years of age17.

Randomized lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk reduction have proven to be feasible and effective18-23. However, translating findings from extensively resourced trials, focused on highly selected populations, into a real-life setting in which resources are limited and populations are more heterogeneous is a difficult task.

The expectation of long-term positive effects of the adherence to a healthy lifestyle has been confirmed in few studies6,10,22. Individuals who had newly adopted a healthy lifestyle in middle age experienced a prompt benefit of lower rates of cardiovascular disease and mortality. A midlife switch to a healthy lifestyle that includes a diet of at least 5 daily fruits and vegetables, exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and not smoking resulted in a substantial reduction in mortality and cardiovascular disease over the subsequent 4 years10.

However, it also has been shown that the acceptance of advice on diet and physical activity and patient actions remain suboptimal9,10. Overall adherence to medical advice, independent of a therapeutic of preventive approach, has been reported to be low in the general population. In a recent meta-analysis, approximately one third of patients who had had myocardial infarction and approximately one half of those who had not had myocardial infarction did not adhere to effective cardiovascular preventive treatment24. In our study, a large interest of patients in taking part of the study was followed by a very discouraging, massive decline in further participation in the follow-up examinations (Figure 1). Higher participation could not be achieved in spite of repeated invitations by phone, e-mail and short-message-system reminders of the next appointment.

Education for cardiovascular prevention is a very important element of the strategies toward improving cardiovascular health in the community. However, the individual perception of health targets may be limited, and preventive measures may therefore be difficult to follow.

Limitations

Interpretation of the results of this study is limited by its design as a case-series type prospective trial. Contrary to case-control studies, only before-after analysis of parameters was possible here.

Conclusions

A simple, basic educational program may improve symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors in an unselected outpatient population, when conducted in a non-coached approach. However, patient adherence remains an important issue to be addressed.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Chaves G, Britez N, Gonzalez G, Oviedo G, Chaparro V, Mereles D. Acquisition of data: Chaves G, Britez N, Oviedo G, Chaparro V. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Chaves G, Britez N, Mereles D. Statistical analysis: Munzinger J, Uhlmann L, Bruckner T, Kieser M, Mereles D. Obtaining financing: Britez N. Drafting of the manuscript: Chaves G, Britez N, Mereles D. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Chaves G, Britez N, Gonzalez G, Achon O, Kieser M, Mereles D, Katus HA. Supervision / as the major investigator: Chaves G, Mereles D.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Report.(WHO) Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. [Accessed 2013 Nov. 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/atlas_cvd/en/

- 2.Lindahl B, Nilssön TK, Borch-Johnsen K, Røder ME, Söderberg S, Widman L, et al. A randomized lifestyle intervention with 5-year follow-up in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: pronounced short-term impact but long-term adherence problems. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(4):434–442. doi: 10.1177/1403494808101373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, et al. Writing Group of the PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobiac LJ, Magnus A, Lim S, Barendregt JJ, Carter R, Vos T. Which interventions offer best value for money in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(7): doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, et al. American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committe. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardoon SL, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG, Capewell S, Morris RW. How much of the recent decline in the incidence of myocardial infarction in British men can be explained by changes in cardiovascular risk factors? Evidence from a prospective population-based study. Circulation. 2008;117(5):598–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.705947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sims M, Maxwell R, Bauld L, Gilmore A. Short term impact of smoke-free legislation in England: retrospective analysis of hospital admissions for myocardial infarction. BMJ. 2010 Jun;340:c2161–c2161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman MD, Capewell S, Ning H, Shay CM, Ford ES, Lloyd-Jones DM. Cardiovascular health behavior and health factor changes (1988-2008) and projections to 2020: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Circulation. 2012;125(21):2595–2602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wofford TS, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB, Labarthe DR. Diet and physical activity of U.S. adults with heart disease following preventive advice. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King DE, Mainous 3rd AG, Carnemolla M, Everett CJ. Adherence to healthy lifestyle habits in US adults, 1988-2006. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuler G, Adams V, Goto Y. Role of exercise in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: results, mechanisms, and new perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2013;62(5):634–637. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raw M, McNeill A, West R. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals. A guide to effective smoking cessation interventions for the health care system. Health Education Authority. Thorax. 1998;53(5):S1–19. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.2008.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, Greenway FL, Hill JO, Phinney SD, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1792–1798. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolly K, Lewis A, Beach J, Denley J, Adab P, Deeks JJ, et al. Comparison of range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: lighten Up randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d6500–d6500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson TA, Palaniappan LP, Artinian NT, Carnethon MR, Criqui MH, Daniels SR, et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention American heart association guide for improving cardiovascular health at the community level, 2013 update: a scientific statement for public health practitioners, healthcare providers, and health policy makers. Circulation. 2013;127(16):1730–1753. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828f8a94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dehghan M, Mente A, Teo KK, Gao P, Sleight P, Dagenais G, et al. Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial (ONTARGET)/Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACEI Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Trial Investigators. Relationship between healthy diet and risk of cardiovascular disease among patients on drug therapies for secondary prevention: a prospective cohort study of 31 546 high-risk individuals from 40 countries. Circulation. 2012;126(23):2705–2712. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villareal DT, Miller 3rd BV, Banks M, Fontana L, Sinacore DR, Klein S. Effect of lifestyle intervention on metabolic coronary heart disease risk factors in obese older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(6):1317–1323. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wister A, Loewen N, Kennedy-Symonds H, McGowan B, McCoy B, Singer J. One-year follow-up of a therapeutic lifestyle intervention targeting cardiovascular disease risk. CMAJ. 2007;177(8):859–865. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood DA, Kotseva K, Connolly S, Jennings C, Mead A, Jones J et alEUROACTION Study Group Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):1999–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King DE, Mainous 3rd AG, Geesey ME. Turning back the clock: adopting a healthy lifestyle in middle age. Am J Med. 2007;120(7):598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eriksson MK, Franks PW, Eliasson M. A 3-year randomized trial of lifestyle intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction in the primary care setting: the Swedish Björknäs study. PLoS One. 2009;4: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012;125(9):882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]