Abstract

Background

Systemic Arterial Hypertension (SAH) is one of the main risk factors for Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), in addition to male gender. Differences in coronary artery lesions between hypertensive and normotensive individuals of both genders at the Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography (CCTA) have not been clearly determined.

Objective

To Investigate the calcium score (CS), CAD extent and characteristics of coronary plaques at CCTA in men and women with and without SAH.

Methods

Prospective cross-sectional study of 509 patients undergoing CCTA for CAD diagnosis and risk stratification, from November 2011 to December 2012, at Instituto de Cardiologia Dante Pazzanese. Individuals were stratified according to gender and subdivided according to the presence (HT +) or absence (HT-) of SAH.

Results

HT+ women were older (62.3 ± 10.2 vs 57.8 ± 12.8, p = 0.01). As for the assessment of CAD extent, the HT+ individuals of both genders had significant CAD, although multivessel disease is more frequent in HT + men. The regression analysis for significant CAD showed that age and male gender were the determinant factors of multivessel disease and CS ≥ 100. Plaque type analysis showed that SAH was a predictive risk factor for partially calcified plaques (OR = 3.9).

Conclusion

Hypertensive men had multivessel disease more often than women. Male gender was a determinant factor of significant CAD, multivessel disease, CS ≥ 100 and calcified and partially calcified plaques, whereas SAH was predictive of partially calcified plaques.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Disease; Hypertension; Plaque, Atherosclerotic; Mens

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been considered a major risk to global health and, therefore it requires many economic and technological investments from governments around the world. The combined efforts of different countries aim to reduce 25% of the world CVD mortality by 2025. In most current programs, special attention is given to patients with risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD), particularly those with diabetes mellitus (DM) dyslipidemia and systemic arterial hypertension (SAH)1,2.

SAH is an important risk factor for the onset of Major Cardiac Events (MACE), and its control is indicated in an attempt to improve prognosis in the middle and long term3. Regarding gender, the prevalence of SAH between men and women is similar; however, a higher rate is observed in men up to 50 years, which reverses after the fifth decade of life4.

The Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography (CCTA) is a noninvasive technique that allows the identification of CAD and of subclinical lesions in the coronary arteries, thus improving the diagnosis and risk stratification of patients with suspected CAD or established disease5-7, with or without SAH. The differences in coronary artery lesions between hypertensive and normotensive individuals of both genders at the CCTA have not yet been clearly determined. The study aims to investigate Calcium Score (CS), coronary artery disease extent and the characteristics of coronary plaques at the CCTA in male and female patients, with and without arterial hypertension.

Methods

This is an observational, analytical, prospective study with 509 patients undergoing CCTA for CAD diagnosis and risk stratification.

Patients aged < 30 years were excluded, as well as those with malignant arrhythmias, pregnancy, renal failure, contraindication to beta-blocker or iodinated contrast use, cancer, decompensated heart failure, resistant SAH, cardiomyopathy and severe valvular heart diseases. The ethical principles governing human experimentation were followed, and all patients signed the free and informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Instituto de Cardiologia Dante Pazzanese.

The CS and the CCTA were performed. Lesion size and characterization of atherosclerotic plaques were analyzed. The 17 arterial segment model described in the American Heart Association classification was used to analyze lesion size and a reduced 12-segment segmentation was used to characterize plaques8.

Clinical, sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics, habits/addictions, comorbidities, presence of symptoms such as typical and atypical angina, risk factors for CAD, medication use and laboratory data were analyzed.

Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total serum cholesterol > 200 mg/dL (after a 12-hour fasting) and hypertriglyceridemia as serum triglycerides > 150 mg/dL (after a 12-hour fasting) or by the use of lipid-lowering agents (statins and/or fibrates). SAH was defined when the measurement of blood pressure at rest, in the sitting position, was ≥ 140 x 90 mmHg or by the use of antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as fasting glucose levels > 126 mg/dL or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents. Laboratory tests were performed at the Laboratory of Instituto de Cardiologia Dante Pazzanese.

The heart rate of all patients was measured one hour before the test. If it was > 65 beats/min, patients received 50‑100 mg oral atenolol (atenolol 50 mg/tablet), or intravenous administration of metoprolol. In case of contraindications to the use of beta blockers, diltiazem was used, at a loading dose of 0.25 mg/kg and after 15 minutes, a maintenance dose of 0.35 mg/kg.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). The CS protocol was performed through CCTA using a 64-channel multidetector tomograph manufactured by Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan MDCT (Aquilion 64) using a 64_0.5 mm collimator; 9.8 to 11.2 detector; 0.39_0.39 mm pixel; rotation time of 350, 375 or 400 ms; 400 or 450 mA current and voltage of 100 or 120 kV (depending on the patient’s body mass index). For plaque detection, the images were reformatted with multiplanar and cross-sectional curves. The protocol included 03-mm thick sections to assess the CS. Then, 0.5 mm sections were obtained to allow coronary assessment. Electrocardiogram modulation (60%-80% of the cardiac cycle) was used to minimize radiation exposure and voltage of 100 or 120 kV according to the patient’s BMI. After the acquisition, the images were transferred to a station for CS and coronary analysis.

The analysis started with the CS calculation according to the method described by Agatston et al9. At each 03 mm of thickness, the operator searched for areas with attenuation factor ≥ 130 HU (Hounsfield units), considering the lesions to be calcified if they had an area of at least 1 mm2. The total score was calculated by adding the lesions. The result was adjusted for gender, ethnicity and age of the patient for classification in risk percentiles10. The CS was stratified into four groups: score zero (none), score 1-99 (light), score 100-399 (moderate), score ≥ 400 (severe). CS was not performed in patients submitted to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous angioplasty.

Using a multiplanar curve format, the operator assessed the coronary tree based on a computerized semi-objective analysis and described the presence or absence of lesions in each of the 17 arterial segments described in the American Heart Association classification8. Plaques were considered hemodynamically significant if they resulted in a reduction ≥ 50% of the sectional area of the vessel lumen or if they were highly calcified and did not allow adequate lumen visualization.

The plaques were divided according to their composition: noncalcified, if they were homogeneous and had an attenuation coefficient < 70UH; partially calcified, if the attenuation coefficient ranged from 71 to 200 UH; and calcified, if the attenuation coefficient was > 200 UH11. When it was impossible to reduce the fluorescent artifact for a calcified plaque, it was interpreted as being a significant stenotic lesion. In case of multiple lesions, the segment analyzed was the one with the worst luminal narrowing.

Imaging Analysis

The CS of the coronary arteries was measured for each calcified plaque using a software program (Vitrea 2, Vital Images, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Image processing, including vessel segmentation, was performed to create multiplanar images and to visualize the entire vessel segment with the narrowed lumen. The cross-sectional images of the vessels could be obtained from any point throughout its length by moving the mouse cursor. The quantitative evaluation of stenosis was based on the ratio between the lumen with minimum contrast and the unaffected proximal and distal lumens with the normal reference.

Coronary stenosis was classified as follows: minimum stenosis: luminal diameter reduced by less than 25%; mild stenosis: luminal diameter reduced by less than 50%; moderate stenosis: luminal diameter reduced by ≥ 50% and < 70%; severe stenosis: luminal diameter reduced by ≥ 70%. A significant reduction of the arterial lumen was considered moderate or severe. For the analysis of the 17 arterial segments, atherosclerotic coronary lesions were further classified into two groups: significant stenosis (> 50% diameter reduction) and non-significant stenosis (< 50% diameter reduction).

The analysis of plaque configuration was performed primarily at the cross-sectional view, classifying them according to the composition: noncalcified plaques (plaques with low attenuation on CT compared with the contrasted lumen with no calcification); partially calcified (calcified and noncalcified elements in the same plate); and calcified plaques (plates with high attenuation on CT compared with the contrasted lumen).

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Results were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Differences in continuous variables between groups were compared using the unpaired t-test when the variable had a normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney test when distribution was not normal. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages and comparisons between groups were carried out using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. The logistic regression models were used to study the association between significant coronary lesions, multivessel involvement, CS ≥ 100, plaque types and risk factors for CAD. The analysis was adjusted for age, gender, DM, SAH, dyslipidemia, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking and family history of CAD.

Results

Of the 509 patients, 369 (72.5%) were hypertensive (HT +), of which 41.7% were males. Among the normotensive patients (HT-) (27.5%), 15.5% were males. The mean age in the HT + group was 61.2 ± 10 years, while in the HT- was 58.9 ± 12 years (p = 0.051) (Table. 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and biochemical characteristics according to SAH

| Characteristics | HT+ Group | HT- Group |

|---|---|---|

| N = 369 (72.5%) | N = 140 (27.5%) | |

| Male gender | 212 (41.7%) | 79 (15.5%) |

| Age | 61.2 ± 10.3 | 58.9 ± 12.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.7 | 26.0 ± 3.7 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 97.6 ± 10.7 | 90.6 ± 11.4 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 112.1 ± 64.1 | 94.8 ± 19.9 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 175.4 ± 48.3 | 181.4 ± 51.8 |

| HDLc (mg/dL) | 48.3 ± 13.2 | 55.8 ± 24.9 |

| LDLc (mg/dL) | 100.8 ± 35.6 | 107.2 ± 43.6 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 154.7 ± 168.2 | 111.5 ± 63.9 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.30 ± 6.2 | 1.0 ± 0.70 |

| DM | 105 (21.3%) | 16 (3.2%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 255 (51.8%) | 60 (1.2%) |

| Family history of CAD | 200 (42.6%) | 64 (13.6%) |

| Sedentary life style | 256 (55.5%) | 86 (18.7%) |

| Previous AMI | 68 (14.3%) | 11 (2.4%) |

| Angioplasty and stent | 28 (5.5%) | 6 (1.2%) |

| CABG | 60 (11.8%) | 12 (2.4%) |

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDLc: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; DM: diabetes mellitus; CAD: coronary artery disease; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting.

After the classification by gender, which showed that 291 patients of 509 (57.2%) were males, new subgroups with and without SAH were defined. The mean age was higher among hypertensive women. As for anthropometric measurements, hypertensive individuals had higher body mass index and waist circumference in both genders. Dyslipidemia was more frequent in hypertensive individuals of both genders, while triglycerides were higher in hypertensive men and HDL was higher in normotensive ones. The presence of DM in the sample was 24.5%, being more frequent in male hypertensive patients, as well as family history of CAD.

Hypertensive men are more sedentary, while athletes of both sexes are more normotensive. The women smokers are more hypertensive.

As for symptoms, there was no difference between typical and atypical chest pain, and dyspnea between groups. However, asymptomatic individuals were more frequently observed in the group of normotensive patients of both genders. Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) was more frequent among hypertensive patients of both genders, as well as medication use. However, there was no difference between the groups regarding prior percutaneous angioplasty, but CABG was more frequent in hypertensive men (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical and biochemical characteristics according to SAH and gender

| Characteristics | Men N = 291 (57.2%) | HT- N = 61 (12%) | HT+ N = 157 (30.8%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT- N = 79 (15.5%) | HT+ N = 212 (41.7%) | p | |||

| Age | 59.7 ± 12.5 | 60.4 ± 10.4 | 0.64 | 57.8 ± 12.8 | 62.3 ± 10.2 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m²) | 26.3 ± 3.8 | 27.8 ± 4.1 | 0.01 | 25.7 ± 3.78 | 29.1 ± 5.41 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 94.6 ± 10.9 | 98.9 ± 10.2 | 0.05 | 85.04 ± 9.18 | 96 ± 11.4 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 98.6 ± 22.4 | 114.8 ± 77 | 0.17 | 89.0 ± 10.89 | 108.2 ± 38.54 |

| Cholesterol total (mg/dL) | 172.1 ± 43 | 170.5 ± 51.1 | 0.85 | 196.2 ± 61.2 | 182.5 ± 43.2 |

| HDLc (mg/dL) | 54.4 ± 29.8 | 44.2 ± 10.4 | 0.01 | 58.1 ± 14.5 | 54.2 ± 14.5 |

| LDLc (mg/dL) | 102.4 ± 34 | 99.5 ± 37 | 0.65 | 114.7 ± 55.5 | 102.6 ± 33.7 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 110.9 ± 62.9 | 15.5 ± 115.3 | < 0.01 | 112.6 ± 66.9 | 125.7 ± 56.9 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 8.3 | 0.56 | 0.98 ± 1.1 | 0.81 ± 0.2 |

| DM | 7 (9%) | 65 (31.0%) | < 0.01 | 9 (15%) | 40 (26.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 32 (41%) | 151 (75. 5%) | < 0.01 | 28 (46.7%) | 104 (67.5%) |

| Family history of CAD | 35 (45.5%) | 144 (62. 6%) | 0.01 | 29 (49.2%) | 86 (57%) |

| Sedentary life style | 41 (53.9%) | 138 (75%) | < 0.01 | 45 (78.9%) | 118 (81.9%) |

| Previous AMI | 8 (11%) | 47 (25. 4%) | 0.01 | 3 (5.2%) | 21 (15%) |

| Angioplasty and stent | 3 (3.8%) | 19 (9%) | 0.14 | 3 (4.9%) | 9 (5.7%) |

| CABG | 8 (10.1%) | 41 (19.3%) | 0.06 | 4 (6.6%) | 19 (12.1%) |

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDLc: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; DM: diabetes mellitus; CAD: coronary artery disease; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting.

The CS was studied in 386 patients without previous CAD. Moderate (≥ 100 and ≤ 399) and severe CS (≥ 400) showed no differences between the HT+ and HT-, even when stratified by gender. The frequency of mild CS (≥ 1 and ≤ 99) was higher in the HT + group in both genders, but without statistical significance. However, it was observed that the male normotensive individuals more frequently had a CS = 0 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of CS according to SAH and gender

| CS | Men N = 209 (54.15%) | HT- N = 54 (13.98%) | HT+ N = 123 (31.89%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT- N = 67 (17.35%) | HT+ N = 142 (36.78%) | p | |||

| None | 31 (43.6%) | 43 (30.3%) | 0.02 | 32 (59.3%) | 56 (45.5%) |

| Mild | 17 (25.4%) | 50 (35.2%) | 0.16 | 14 (25.9%) | 43 (35%) |

| Moderate | 9 (13.4%) | 24 (16.9%) | 0.52 | 6 (11.1%) | 14 (11.4%) |

| Severe | 10 (14.9%) | 25 (17.6%) | 0.63 | 2 (3.7%) | 10 (8.1%) |

CS: calcium score.

CCTA results were normal in 26% of hypertensive patients versus 45% of normotensive individuals. The calculated CS percentages were higher and the presence of significant lesions was more frequent in hypertensive patients, of both genders. The presence of triple-vessel disease and the number of segments with atherosclerotic plaques showed higher frequency in hypertensive men (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of CCTA findings according to SAH and gender

| Findings | Men N = 291 (57.2%) | HT- N = 61 (12%) | HT+ N = 157 (30.8%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT- N = 79 (15.5%) | HT+ N = 212 (41.7%) | p | |||

| Normal results | 29 (36.7%) | 35 (83.5%) | < 0.01 | 34 (55.7%) | 61 (38.9%) |

| Percentiles | 33.3 ± 35.8 | 47.6 ± 37.6 | 0.01 | 26.8 ± 37.6 | 41.7 ± 40.36 |

| Significant CAD | 26 (32.9%) | 107 (50.5%) | 0.01 | 9 (14.8%) | 45% (28.7%) |

| Multivessel (3 vessels) | 6 (7.6%) | 46 (21.7%) | < 0.01 | 1 (1.6%) | 11 (7%) |

| Number of normal segments | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 11.4 ± 2.9 | < 0.0001 | 13.0 ± 1.9 | 12.9 ± 2.5 |

| Number of atherosclerotic segments | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 2.7 | < 0.0001 | 1.95 ± 1.52 | 2.24 ± 1.83 |

CAD: coronary artery disease.

As for the multivariate logistic regression, the factors associated with significant lesions were dyslipidemia, male gender and age. Regarding disease involvement in two vessels, the factors were dyslipidemia, male gender and age. On the other hand, multivessel involvement (three vessels) was associated with dyslipidemia, male gender and age. Hypertensive men had a higher probability (OR = 2.3) for lesions in three vessels, but without statistical significance. CAD extent was independently associated with dyslipidemia (OR = 6.01), male gender (OR = 2.73) and age (OR = 1.03). High CS was associated with male gender and age (Table 5).

Table 5.

*Multivariate logistic regression for variables associated with coronary artery lesions

| Variable | Significant stenosis | Multivessel involvement (2 vessels) | Multivessel involvement (3 vessels) | p | Odds Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | p | Odds Ratio | p | Odds Ratio | |||

| Age | 1.052 (1.027-1.076) |

< 0.001 | 1.039 (1.012-1.066) |

0.004 | 1.048 (1.014-1.084) |

0.004 | 1.087 (1.56-1.118) |

| Male gender | 2. 883 (1.763-4.714) |

< 0.001 | 2.732 (1.583-4.715) |

< 0.001 | 4.270 (2.011-9.069) |

< 0.001 | 2.840 (1.612-5.002) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2.829 (1.661-4.816) |

< 0.001 | 6.017 (2.882-12.562) |

< 0.001 | 5.822 (1.994-16.997) |

< 0.001 | 1.635 (0.929-2.878) |

| Obesity | 1.996 (1.149-3.468) |

0.014 | - | - | - | - | - |

| HT+ | - | - | - | - | 2.317 (0.963-5.577) |

0.061 | |

Adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, family history of CAD, physical activity and smoking; SAH: systemic arterial hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; CAD: coronary artery disease.

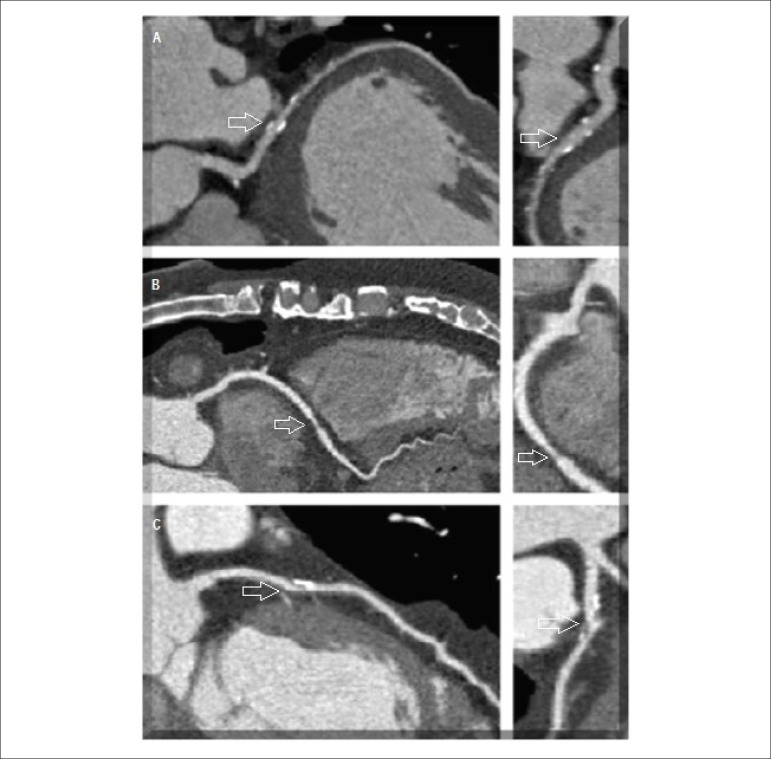

The presence of calcified plaque was independently associated with DM (OR = 2.33), dyslipidemia (OR = 2.05), male gender (OR = 2.01) and age (OR = 1.08). For non-calcified plaque, age was the only associated factor (OR = 1.05). Male gender and dyslipidemia had a higher probability, but without statistical significance. SAH was a predictive risk factor for the presence of partially calcified plaques (OR = 3.9), as well as male gender (OR = 1.72) and age (OR = 1.08) (Table 6). Figure 1 shows plaque composition at the CCTA.

Table 6.

*Logistic regression for variables associated with the types of plaques

| Variable | Calcified Plaque | Non-Calcified Plaque | Odds Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | p | Odds Ratio | p | ||

| Age | 1.091 (1.059-1.125) | 0.001 | 1.058 (1.023-1.095) | 0.001 | 1.085 (1.047-1.125) |

| Male gender | 2.015 (1.146-3.544) | 0.015 | 1.951 (0.963-3.952) | 0.064 | 1.712 (1.03-2.84) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2.058 (1.159-3.655) | 0.014 | 1.881 (0.904-3.914) | 0.091 | - |

| DM | 2.332 (1.194-4.557) | 0.013 | - | - | - |

| HT+ | - | - | - | - | 3.979 (1.486-10.654) |

Adjusted for age, gender, SAH, DM, dyslipidemia, obesity, family history of CAD, physical activity and smoking; SAH: systemic arterial hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; CAD: coronary artery disease.

Figure 1.

Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. (A) Calcified plaque; (B) Partially calcified plaque

Discussion

In this study, the extent of CAD was assessed by high CS, presence of significant lesion and multivessel involvement. The main risk factors predictors of CAD were dyslipidemia and male gender. However, SAH was associated with the presence of partially calcified plaque (OR = 3.9). We emphasize the lack of difference between the groups with all levels of the CS, except for the important contribution of zero CS, more frequent in normotensive men.

An association was observed between partially calcified plaque and SAH, male gender and age; moreover, the calcified plaque was associated with DM, dyslipidemia, male gender and age. Rivera et al.12, in a multivariate analysis, showed that SAH was predictive of any type of plaque in asymptomatic individuals, and as for the partially calcified plaque, they obtained similar results to those found in the present study, in which SAH (OR = 2.33; 95% CI = 1.10 to 4.95) and male gender (OR = 5.54; 95% CI = 1.84 to 16.68) were predictors of this type of plaque. However, the study population was different from the sample by excluding previous DAC.

In a study that analyzed the type of plaque at CCTA between the group with and without metabolic syndrome (MS)13, it was observed that among the types of plaque, the highest frequency of partially calcified plaque was found in patients with MS. Older age and male gender were associated with both the presence of calcified and noncalcified plaque. At the adjusted analysis, MS was associated with partially calcified plaque, as well as male gender and age, data consistent with our results.

In a study carried out in 2008 with a population with no prior CAD at CCTA14, there were similarities in the results in comparison with this study, as the partially calcified plaque was associated to SAH and age.

Additionally, the multivariate analysis showed the highest association of partially calcified plaque with SAH, followed by male gender and age.

In this study, the calcified plaque was associated with DM, dyslipidemia and male gender, with similar odds ratio. Studies have shown that calcification of the coronary arteries is associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Most significant stenotic lesions are calcified and 90% of CAD patients have calcification15,16. It can be inferred that these risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and male gender are important for the presence of CAD and increased cardiovascular risk.

In the classical literature, SAH is shown as an important cardiovascular risk factor. There are, however, recent studies showing this association of SAH and coronary heart disease, but with questionable impact on clinical practice. A follow‑up study17 showed that there was no significant difference in MACE rates between normotensive and hypertensive patients, although the hypertensive patients submitted to CCTA had a higher prevalence of obstructive CAD and more extensive atherosclerotic lesions. It thus suggests that patients without obstructive CAD have an excellent prognosis, regardless of the presence of SAH.

In this study, male gender was associated with the presence of calcified and partially calcified plaques, in addition to CAD extent as demonstrated by the high CS and presence of triple-vessel disease, and the number of segments with atherosclerotic plaques with greater frequency in the male HT + group. In Brazil, CAD is the leading cause of death in both genders, in all regions of the country18, and is the first cause of morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients19.

The difference between the CAD mortality rates between men and women in Brazil is one of the lowest in the world, both due to high rates of death among women as well as a steeper decline in mortality rates and risk factors among men18.

By the age of 40 women have lower risk of CAD compared to men. The male gender has a 49% chance, whereas females have 32%. In men, the first event occurs around age 65; while in women the first event usually occurs five to ten years later. However, this increase occurs in different ways for both sexes, with the female gender showing a remarkable increase at older ages, thus decreasing the difference between the genders20. These data corroborate those of present study, as the mean age of the sample was not advanced age; among hypertensive patients it was 61.2 ± 10.3 and for normotensive patients, 58.9 ± 12.6 years, with men showing a higher frequency of CAD at this age range. This showed an association with CAD extent assessed by the presence of significant lesion, multivessel involvement and high CS, and with calcified and partially calcified plaques.

In a multicenter study19, the data analysis of 8,737 patients with suspected or known CAD, followed for a mean of 25 months for the occurrence of all-cause mortality or nonfatal myocardial infarction, in the subgroup of female patients with known CAD and positive test for myocardial ischemia, the event rate was higher in women (p = 0.01) and no gender differences were observed in patients with negative test for induced ischemia (p = 0.3). In the group of non-ischemic individuals, the annual event rate was worse in men than in women aged less than 65 years (p <0.0001) and older than 65 years (p = 0.04). One can infer that the data related to the study are similar to this one, as it shows the male gender as a predictor of major cardiac events and death, since in this research it is associated with CAD extension. However, these data suggest analyzing a cohort of our population for assessment of cardiac outcomes aiming at more precise comparisons.

Limitations

This study has internal validity, as all patients undergoing this methodology at IDPC, from November 2011 to December 2012 were included; due to limited availability of coronary angiography method in most public hospitals in the country to date, it has a low external validity. Additionally, CCTA findings were not compared with other methods such as coronary ultrasound for validation21.

Conclusion

Hypertensive men more frequently have multivessel disease. Male gender was the determining factor of significant CAD, multivessel disease, high calcium score and calcified and partially calcified plaques, while SAH was a predictor of the presence of partially calcified plaque.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Oliveira JLM, Hirata MH, Tavares IS, Pinto IMF. Acquisition of data: Oliveira JLM, Gabriel FS, Hirata TDC, Tavares IS, Melo LD, Dória FS. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Oliveira JLM, Gabriel FS, Tavares IS, Melo LD, Dória FS. Statistical analysis: Oliveira JLM, Sousa ACS, Pinto IMF. Obtaining financing: Oliveira JLM, Hirata MH, Pinto IMF. Writing of the manuscript: Oliveira JLM, Hirata MH, Tavares IS, Pinto IMF. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Oliveira JLM, Hirata MH, Sousa AGMR, Tavares IS, Sousa ACS, Pinto IMF.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by CNPq.

Study Association

This article is part of the thesis of Post-Doctoral submitted by Joselina Luzia Menezes Oliveira, from Instituto Dante Pazzanese de Cardiologia.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. (WHO) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howitt P, Darzi A, Yang GZ, Ashrafian H, Atun R, Barlow J, et al. Technologies for global health. Lancet. 2012;380(9840):507–535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao D, Guo Y, Ning W, Niu X, Yang J. Computed tomography for detecting coronary artery plaques: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes NH, Paulitsch FS, Pereira AC, Gois AF, Gagliardi A, Garzillo CL, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on the outcome of patients with stable coronary artery disease: 2-year follow-up of the MASS II study. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19(6):383–388. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328306aa8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia I Diretriz de ressonância e tomografia cardiovascular. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;87(supl.3):1–12. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2006001600034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugliese F, Mollet NR, Runza G, van Mieghem C, Meijboom WB, Malagutti P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive 64-slice CT coronary angiography in patients with stable angina pectoris. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(3):575–582. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cademartiri F, La Grutta L, Palumbo AA, Maffei E, Runza G, Bartolotta TV, et al. Coronary plaque imaging with multidetector computed tomography: technique and clinical applications. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(Suppl 7):M44–M53. doi: 10.1007/s10406-006-0195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51(4) Suppl:5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(4):827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-gender-race percentiles-The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(4):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enrico B, Suranyi P, Thilo C, Bonomo L, Costello P, Schoepf UJ. Coronary artery plaque formation at coronary CT angiography: morphological analysis and relationship to hemodynamics. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(4):837–844. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Cox PR, Cho EK, Yoon Y, Cho I, et al. Association of traditional cardiovascular risk factors with coronary plaque sub-types assessed by 64-slice computed tomography angiography in a large cohort of asymptomatic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206(2):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim S, Shin H, Lee Y, Yoon JW, Kang SM, Choi SH. Effect of metabolic syndrome on coronary artery stenosis and plaque characteristics as assessed with 64-detector row cardiac CT. Radiology. 2011;261(2):437–445. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamberg F, Dannemann N, Shapiro MD, Seneviratne SK, Ferencik M, Butler J, et al. Association between cardiovascular risk profiles and the presence and extent of different types of coronary atherosclerotic plaque as detected by multidetector computed tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(3):568–574. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arad Y, Spadaro L, Goodman K, Lledo-Perez A, Sherman S, Lerner G, et al. Predictive value of electron beam computed tomography of the coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;93(11):1951–1953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budoff MJ, Young R, Lopez VA, Kronmal RA, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, et al. Progression of coronary calcium and incident coronary heart disease events: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(12):1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamitzky M, Meyer T, Hein F, Bischoff B, Byrne RA, Martinoff S, et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography in patients with arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28(3):641–650. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.astanho VS, Oliveira LS, Pinheiro HP, Oliveira HC, Faria EC. Sex differences in risk factors for coronary heart disease: a study in a Brazilian population. BMC Public Health. 2001;1:3–3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortigiani l, Sicari R, Bigi R, Landi P, Bovenzi F, Picano E. Impact of gender on risk stratification by stress echocardiography. Am J Med. 122(3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vitale C, Gebara O, Fini M, Wajngarten M, Aldrighi JM, Silvestre A, et al. Different effect of hormone replacement therapy, DHEAS, and tibolone on endotelial function in post-menopausal women with increased cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(Suppl 1):239A–239A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voros S, Rinehart S, Qian Z, Joshi P, Vazquez G, Fischer C, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis imaging by coronary CT angiography: current status, correlation with intravascular interrogation and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(5):537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]