Abstract

Manufacturers launching next-generation or innovative medical devices in Europe face a very heterogeneous reimbursement landscape, with each country having its own pathways, timing, requirements and success factors. We selected 2 markets for a deeper look into the reimbursement landscape: France, representing a country with central decision making with defined processes, and Italy, which delegates reimbursement decisions to the regional level, resulting in a less transparent approach to reimbursement. Based on our experience in working on various new product launches and analyzing recent reimbursement decisions, we found that payers in both countries do not reward improved next-generation products with incremental reimbursement. Looking at innovations, we observe that manufacturers face a challenging and lengthy process to obtain reimbursement. In addition, requirements and key success factors differ by country: In France, comparative clinical evidence and budget impact very much drive reimbursement decisions in terms of pricing and restrictions, whereas in Italy, regional key opinion leader (KOL) support and additional local observational data are key.

Keywords: reimbursement, market access, reimbursement system, reimbursement requirements, medical devices, France, Italy, clinical evidence, price

Manufacturers developing new devices in diabetes have to investigate the reimbursement situation for the new product some time prior to launch. Manufacturers will discover that the reimbursement landscape for next-generation and innovative medical devices in Europe is very heterogeneous. Each country has its own reimbursement pathways, requirements and stakeholders. Some countries implemented the decision-making process on a national level, others decide on a regional or local level. Whereas some countries follow a process with defined steps and criteria, others leave decision making to individuals and their evaluation criteria.

In this article, we want to provide an overview of the reimbursement systems in 2 countries which differ to a great extent: France, as a country with a defined, centralized reimbursement process, and Italy, which is organized regionally and less transparent in its reimbursement approach. We focus on medical devices which are prescribed in the outpatient setting in the public system. We first provide an overview on the reimbursement of existing products, focusing on blood glucose monitoring (BGM), continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and telehealth. Second, we describe reimbursement options, pathways, stakeholders, and requirements for next-generation and innovative diabetes products.

The article is based on our experience working for various device manufacturers on exploring reimbursement opportunities and requirements for new products, and analyses of past reimbursement decisions.

Obtaining Reimbursement in France

France has a centralized health care system in which reimbursement decisions are made at a national level, and are then binding in the entire country. Two distinct authorities drive the process: Commission Nationale d’Evaluation des Dispositifs Médicaux (CNEDiMTS; national committee for the evaluation of medical devices and health technologies) is responsible for assessing the clinical benefit of a new product and Comité Economique des Produits de Santé (CEPS, national commission responsible for pricing) manages price negotiations in a second step. The reimbursement of diabetes technologies in the outpatient setting is based on a tariff system. All reimbursable devices and services and their respective tariffs are listed in the Liste des Produits et Prestations Remboursables (LPPR; list of reimbursed products and services).

Current Reimbursement Situation for Selected Medical Devices

BGM strips are fully covered, and patients on insulin do not face any volume restrictions. For patients not treated with insulin (type 2, gestational diabetic patients, etc), however, a slight restriction on the number of tests was introduced in February 2011, limiting the maximum strips to 200 per year and patient. However, payers are more restrictive when it comes to reimbursement levels. Strips of almost all BGM systems are reimbursed based on a single “generic” tariff. This means that French payers do not see any relevant differences in the various BGM systems which should be addressed by differentiating tariffs and reimbursement levels. In other words, improvements in accuracy or features driving convenience are not rewarded. In the case of BGM technologies which cannot be covered by the generic tariff, French payers have to create a brand-specific tariff. However, this does not necessarily result in a premium reimbursement, as Roche’s Accu-Chek Mobile System shows. In addition, payers are increasing the pressure on BGM prices: The strip tariff has been recently slightly decreased.

Similar to other countries, CGM is reimbursed based on individual case-by-case decisions only. The positive news in December 2013 was that France is among the few countries open to covering CGM on a regular basis. CNEDiMTS has approved Abbott’s FreeStyle Navigator II for coverage.1 However, price negotiations between CEPS and Abbott are still ongoing (as of October 2014). Since the benefit evaluation of CNEDiMTS resulted in only a “minor improvement,” we assume that the price expectations of the French authorities are by far below the current prices. Furthermore, its reimbursement will be restricted to a small population, that is, patients with type 1 diabetes with HbA1c ≥ 8% despite a compliant insulin therapy (external pump or multiple daily injections for at least 6 months with BGM ≥ 4 times/day), which is around 6,000-12,500 patients, as estimated by the CNEDiMTS.

In the area of telehealth application, there is currently no reimbursement in place.

Introducing Next-Generation Products by Accepting Existing Reimbursement

In France, a next-generation product has the option of being reimbursed under a generic tariff of the LPPR list immediately after a CE mark was provided. This option is applicable if at the time of registration, another similar device already exists in the LPPR list. In this case, the manufacturer has to accept the existing reimbursement level. Targeting the generic description is a fast and easy process. The manufacturer applies for inclusion of the new product by submitting a “declaration of inscription.” Based on indications and technical specifications described in detail in this document, a manufacturer can self-inscribe the new product into a certain LPPR generic line without mentioning the brand and/or company name. This registration is simply done via the ANSM (Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé) website, where all necessary process steps are again explained. As soon as registration is completed, the manufacturer only has to label his/her product with the appropriate code for coverage and from this time on reimbursement is obtainable under an existing LPPR tariff. The maximum selling prices can then be set by the CEPS according to the standard tariff of the product group. CNEDiMTS does not evaluate the product when first included.

Gaining Sufficient Reimbursement for Next-Generation Products and Innovations

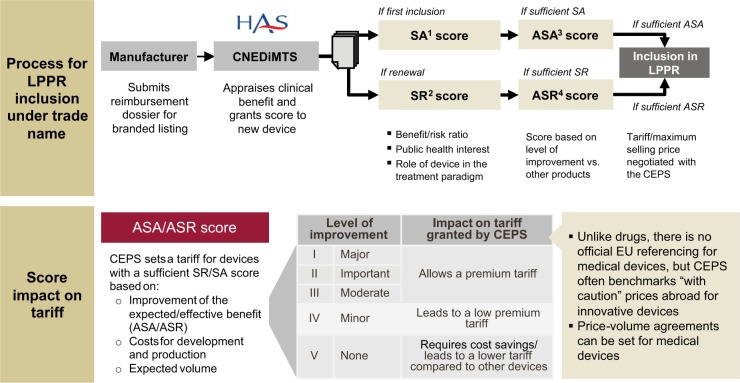

If existing reimbursement tariffs are not sufficiently high to cover the product’s target price, or if the new technology cannot be classified into a generic product group, manufacturers have to achieve adequate coverage under a new, specific tariff. The manufacturer will have to apply for inclusion of the device on the LPPR list under its own trade name (see Figure 1), a time-consuming process that includes a comprehensive technology assessment.

Figure 1.

Process of obtaining reimbursement for innovative medical devices in France.

The process for LPPR inclusion under a trade name is initiated by the manufacturer by submitting a reimbursement dossier for a branded listing at the CNEDiMTS. The comprehensive dossier requires information on manufacturer and product details, clinical evidence available, health economic data, manufacturer’s suggested price along with justification for the price claim, as well as projected market size (forecasted volume for first 3 years). CNEDiMTS then assesses if the product is needed from a public health perspective, and evaluates the added value compared to existing alternatives. The results of the assessment are summarized in scores: an SA score (Service attendu), which has to be “sufficient” to continue with the assessment, and an ASA score (Amélioration du service attend), which measures the new product’s level of improvement in comparison to the most appropriate comparator in its field and which, in turn, determines the basis for discussions about price. ASA ratings of I, II, and III (ie, major, important, and moderate) support a significant premium tariff, while a rating of VI (minor) leads only to a low premium tariff and V (no improvement) to a tariff even lower than what is currently reimbursed for comparable diabetes devices. At the moment most devices are rated IV or V and ratings of I to III are not granted. If CNEDiMTS includes a product in the LPPR under a trade name, tariffs are negotiated between the manufacturer and CEPS according to expected medical benefit the innovative product delivers as well as expected sales volume, that is, budget impact.

The branded listing pathway is difficult and resource-consuming as a new product has to demonstrate a medical benefit with comparative clinical data. Furthermore, this kind of LPPR listing represents only a temporary solution since, as soon as a competitor enters the market, the creation of a generic description could be justified.

Examples of Past Reimbursement Decisions

To better understand the key success factors in this process, we analyzed past reimbursement decisions by the French authorities. The cases of Medtronic-MiniMed Paradigm Veo and Abbott’s FreeStyle Navigator II revealed that clinical data requirements are very high in France. Similar to pharmaceuticals, only randomized, controlled trials ensure sufficient reimbursement. In the case of medical devices, open-label trials seem to be accepted.

Medtronic Pump and CGM—MiniMed Paradigm Veo

Medtronic submitted an application for inclusion on the LPPR list for its insulin pump MiniMed Paradigm Veo back in 2010. The new system has also CGM functionalities. CNEDiMTS evaluated the new system based on 6 prospective, randomized, multicenter, open-label studies,2 involving CGM with insulin pump or multiple daily injections. However, none of these studies included specifically MiniMed Paradigm Veo. For this reason CNEDiMTS concluded that the delivered benefit was insufficient (SA score). CNEDiMTS acknowledged that CGM is associated with better glycemic control, but asked for clinical studies proving the efficacy of CGM in association with an insulin pump compared to insulin pump therapy alone.

In addition, Paradigm Veo has the unique feature to block insulin administration, but the studies did not prove that an automatic 2-hour interruption of insulin administration changes outcome.

However, the evaluation results of Paradigm Veo did justify temporary reimbursement in special cases to allow the manufacturer to generate the necessary clinical and/or economic data. Hence, reimbursement would be granted under the condition of further data generation.

Abbott FreeStyle Navigator II

Since both patients and physicians are increasingly demanding broader usage of CGM systems, CNEDiMTS conducted a health technology assessment of a continuous glucose blood monitoring system in patients with type 1 diabetes. The evidence evaluated by the board comprised 3 prospective multicenter, noncomparative studies and 2 prospective randomized, multicenter, open-label studies (of which the latter were considered in the final assessment in the end) focusing on relevant endpoints such as reduction of HbA1c, incidence of hypoglycemic episode, and improved patient insulin therapy management. Within the provided clinical studies the CNEDiMTS found sufficient proof (assigning a score of ASA IV—minor improvement compared to BGM) to grant reimbursement for the specified indication; however, it also limited its covered usage to a specific subpopulation.

Obtaining Reimbursement in Italy

In some European countries, regional or local health authorities are granted more responsibilities in deciding about reimbursement of existing or new products, Italy is a prime example. While national authorities can still purchase devices, monitor their usage, and allow products on or exclude them from the market, they rarely use their power in the area of medical devices in diabetes. In addition, a national clinical guideline on diabetes treatment and monitoring exist (“Italian Standards for Diabetes Care—Guidelines 2009-2010”). However, the guideline is not binding for the regions and are mostly considered to be only recommendations. Therefore, reimbursement decisions are very much left to each individual regional health authority.

Current Reimbursement Situation for Selected Medical Devices

BGM meters are generally provided by the local health units to their resident patients for free. In regions with “indirect distribution,” BGM strips are distributed by community pharmacies. Similar to France, all strips are reimbursed at the same price, disregarding any feature or performance differences in the systems. In regions with “direct distribution,” for example, Emilia Romagna and Liguria, disposables are centrally purchased through tenders and distributed to patients through local health units (Aziende Sanitarie Locali; ASLs). The observation is that tenders are very much price driven. Although various technology features and services are requested, price remains the most important criterion with more than 50% weight. In addition, some regions restrict strip usage beyond what national guidelines recommend to control overuse, for example, 125 strips/month for patients on insulin with >2 injections/day.

Although addressed in national guidelines, CGM is usually not even mentioned at the regional level for reimbursement. Funding decisions for CGM are made case by case and are based on physicians’ justifications. Recently it could be noted that some regions, for example, Lazio, Veneto, and Basilicata, became more open to CGM for self-monitoring, though still at a low level. Additional regions are expected to follow this example and adopt CGM usage for self-monitoring of insulin diabetes patients.

The same situation occurs for telehealth applications: Currently regions have no standard reimbursement in place; therefore, a case-by-case reimbursement regulation applies. However, some ASLs are currently running pilot programs for telehealth to assess the potential and delivered benefits, which could result in general reimbursement terms in the future.

Introducing Next-Generation Products by Accepting Existing Reimbursement

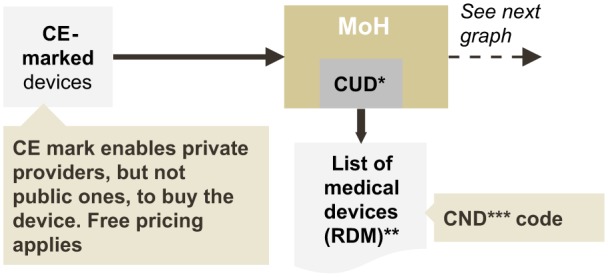

To achieve reimbursement, a product must be registered and listed on the national list of medical devices, which usually takes between 4 and 8 months. Next-generation products will be classified under an existing CND code (“Commissione unica sui dispositivi medici”). These codes have no impact on reimbursement decisions, as the coding is merely an administrative issue and the reimbursement is decided by the regions (see Figure 2). Once the product is classified, regions can include them in tenders or regional reimbursement guidelines.

Figure 2.

Registration process on the national list of medical devices.

For next-generation products comparable to currently available devices, the manufacturer might be able to achieve a small price premium in tenders. To do so, key opinion leader (KOL) support is required since they are involved in defining the specifications and evaluating the different products. However, considering the experience with BGM, chances of success in this regard are rather low. We observe that tenders place a very high weight on price with more than 50% in the scoring model, leaving very limited room to differentiate a next-generation product.

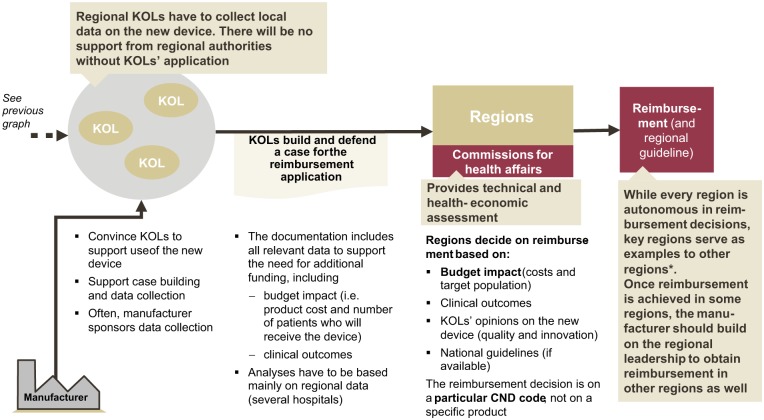

Gaining Reimbursement for Innovations

The reimbursement process for innovations is less systematic than in France and takes about 1-2 years (see Figure 3). Innovations must also be included in the list of medical devices and a new CND code has to be created. Regions will then decide whether or not to cover the new product. Assessment criteria and rules are not documented and publicly available, but in discussions regional authorities reveal that they usually base their decision on budget impact, clinical outcome and evidence, KOL opinion and recommendations by national guidelines. In terms of evidence, multinational trials are of course considered, but payers also expect local data to evaluate local usage patterns, cost, and budget impact. In this regard, payers expect prospective observational studies (and not randomized controlled trials), particularly for innovations with large budget impact.

Figure 3.

Process of obtaining reimbursement for innovative medical devices in Italy.

Even if regional authorities are autonomous in the reimbursement decision making, KOL support is crucial. If the manufacturer involves KOLs and the scientific community already in the trial phase, data collection for key regions could start earlier, which would speed up the reimbursement process and might reduce the overall time needed. Furthermore, KOLs are needed to trigger the reimbursement process in a region: Regional authorities will especially listen to KOLs but not necessarily to manufacturers when deciding on funding a new technology.

Regions might also consider HTAs (health technology assessments) from the national agency Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali (national agency for regional health services). Some regions have started implementing their own HTA organizations as an additional source for reimbursement decisions, for example, Emilia Romagna, Lombardy, Veneto, and Piedmont. Although the intensity of activities is still low, they might gain influence in the future.

Due to the aforementioned pattern of regions considering recommendations and guidelines of other regions, the manufacturer should focus reimbursement efforts on the most referenced regions which are Emilia Romagna, Lombardy, Veneto, and Tuscany. It is still necessary to approach several regions for fast market penetration.

Examples of Recent Efforts to Obtain Reimbursement in the Area of Telehealth

Regions and local health units or hospitals are open to cooperating with manufacturers, and several pilot programs around telehealth applications exist in Italy, addressing the issue that many diabetes patients do not correctly measure their blood glucose level.

Data Transfer

An interesting teleheath program has recently been introduced by the hospital Città della salute e della scienza in cooperation with Eli Lilly and Bis-Care.3 The BGM device is designed to communicate with smartphones, which then transfer the collected information to a central server. Patients’ data are analyzed in real time and physicians can send messages to their patients and make suggestions on changing the treatment based on the delivered information. Consequently, the patient is able to better monitor and promptly adjust the treatment if needed. The health care budget might finally benefit from the program through reduced number of patient visits as well as more effective usage of products. If the desired outcome can be shown, the hospital may have a promising case to present at the regional authority to obtain reimbursement.

Web Portal

A similar approach is pursued by “PODIO” (Portale Orientato Diabetologia Infantile Ospedaliera), a web portal for better management of diabetes in pediatric patients, offering a cloud approach for all stakeholders.4 The program was introduced and implemented in late 2011/early 2012 to address the need for shared guidelines and common treatment approaches of all parties involved, that is, specialists, GPs, pharmacies, and so on. The web portal provides personalized information and supports patients interactively by analyzing their current situation and needs. The pediatric patient’s family can communicate with the physician through the web portal via PC or smartphone. By improving patient involvement and communication, overall diabetes management of pediatric patients is highly likely to improve.

Summary

European reimbursement systems for devices in diabetes vary, for example, in terms of decision level (national vs regional or local), payment system (based on tariffs vs tenders), and transparency of the process. France and Italy are examples of 2 different systems.

In France, reimbursement of devices is managed on a national level and based on tariffs. Many “generic” tariffs exist which cover several different brands. If applicable, next-generation products can use existing generic tariffs and accept the current reimbursement level. A next-generation product seeking for premium reimbursement or an innovative product will have to undergo a defined and transparent process with an assessment of the medical need and added value compared to current standard. The evaluation will determine the price level that payers expect in the subsequent price negotiation. French payers are very evidence driven, thus a solid clinical study basis is key to achieve a positive reimbursement decision. For a major innovation, at least 1 high-quality randomized clinical trial is expected (see recent CGM system evaluation). Payers also consider the budget impact, and are increasingly more interested in health economic data (now mandatory).

In Italy, the national level has the authority to regulate and organize health services, but in the area of diabetes devices, decision making is left to the regions. As a result, reimbursement levels and prices vary by region, as the example of BGM shows. Some regions apply a tariff systems with BGM managed under a single tariff, others reimburse devices based on tenders. Next-generation products accepting the current market prices might be covered by existing tariffs or can participate in tenders. Next-generation products seeking for premium reimbursement or innovative products have to undergo a more comprehensive evaluation process on a regional level. Processes are not defined. Due to the increasing pressure to reduce health care expenditure, the price and the overall budget impact are important factors in the reimbursement decision for new technologies in diabetes. However, KOL support is essential to obtain reimbursement for an innovation or premium reimbursement for a next-generation product. Health authorities listen to KOLs, who ultimately trigger the reimbursement decision. Therefore it is advisable to involve KOLs as early on as possible, ideally already in the clinical trials. Furthermore, observational local data are important, allowing the authorities to calculate the budget impact based on usage patterns in Italy.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ASL, Aziende Sanitarie Locali; BGM, blood glucose monitoring; CEPS, Comité Economique des Produits de Santé; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CNEDiMTS, Commission Nationale d’Evaluation des Dispositifs Médicaux; HTA, health technology assessment; KOL, key opinion leader; LPPR, Liste des Produits et Prestations Remboursables.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. HAS Avis de la CNEDiMTS. www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-12/freestyle_navigator_ii.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2014

- 2.HAS Opinion. www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2012-03/paradigm_veo__2711__english_version.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2014

- 3.09/2013 Torino: primo progetto italiano di telemedicina in diabetologia, presso la Città della Salute. www.regione.piemonte.it/sanita/cms2/notizie-87209/notizie-dalle-asl-e-dalle-aso/2107-03092013-torino-primo-progetto-italiano-di-telemedicina-del-paziente-diabetico-mediante-controllo-remoto-della-glicemia-presso-la-citta-della-salute. Accessed October 22, 2014

- 4. Portale Orientato Diabetologia Infantile Ospedaliera. www.policlinico.unina.it/siti/podio/index.php. Accessed October 22, 2014