Highlights

-

•

Surgeons should approach the acute abdomen with a broad differential.

-

•

CT is a valuable diagnostic tool in the evaluation of adult intussusception.

-

•

Laparoscopy is a useful adjunct for diagnosis and treatment of intussusception.

-

•

There is a limited role of reduction prior to resection in very select cases.

Keywords: Embolize, Intussusception, Resection, Reduction

Abstract

Introduction

Although more commonly thought of as a surgical problem affecting children, surgeons evaluating the adult acute abdomen should remain vigilante in diagnosing intussusception. In this case series, we reviewed 6 years of medical records at a community teaching hospital in order to analyze the etiology, presentation, and management of nine cases of adult intussusception.

Presentation of cases

Most of the patients in our series shared symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Computed tomography scan was crucial in distinguishing adult intussusception from other causes of acute abdomen. Eight patients underwent operative exploration, five of whom underwent bowel resection. One patient’s symptoms resolved with no surgical intervention. All nine patients had excellent outcomes.

Discussion

Although detailed history and physical examination are essential in all cases of acute abdomen, CT scan findings of “target” signs are pathognomonic of intussusception. Laparoscopy should be strongly considered in select cases. Current literature suggests that reduction may be performed before resection if the lesion meets certain stringent parameters. The primary concern with regards to reduction before resection is potential embolization of malignant cells. Colonic intussusception is almost always treated with resection without reduction, while small intestinal intussusception could be treated by reduction before resection, if the small bowel lead points are less likely to be malignant.

Conclusion

Intussusception is a rare but serious etiology of the acute abdomen in adults. Each case should be evaluated independently according to the specific type of lead-point lesion. Excellent outcomes may be anticipated with prompt diagnosis and surgical treatment.

1. Introduction

Intussusception is a process in which a segment of bowel telescopes into an adjoining segment, leading to bowel obstruction (Fig. 1). It is the leading cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but in adults, it represents only 1% of cases [1,2]. Intussusception can be attributed to a number of triggers or lead points. The etiology in children tends to be idiopathic or viral in origin, while adult cases are more generally linked to a distinct lesion in the intestinal wall that alters normal peristalsis [1,3]. About 65% of adult cases are secondary to neoplasm [4]. The remainder may be benign or congenital [4]. Cases are described as enteric (affecting only the small bowel), colonic (affecting only the large bowel), ileo-colic (small bowel telescoping into large bowel), or ileo-cecal (small bowel telescoping into cecum) [2,4,5].

Fig. 1.

Ileocecal anatomy showing intussusception.

Source: http://www.yoursurgery.com/ProcedureDetails.cfm?BR=1&Proc=81.

1.1. Methods

This retrospective study was performed at a community teaching hospital by reviewing all symptomatic cases of adult intussusception between 2008 and 2014. The findings of nine patients between the ages of 20 and 85 years old were analyzed. In this series, four patients were males and five were females. Presenting symptoms, etiology of intussusception, course of treatment, and outcomes of all cases were reviewed. Diagnosis was corroborated by CT scan in all cases. The spectrum of treatment included non-operative management, laparoscopic assisted surgery, and open surgery with or without bowel resection (Figs. 2–7 ).

Fig. 2.

Classic “target” sign indicating intussusception from case #1.

Fig. 3.

Abdominal CT indicating intussusception from case #2.

Fig. 4.

Axial CT showing intussusception from case #9.

Fig. 5.

Coronal CT showing intussusception from case #9.

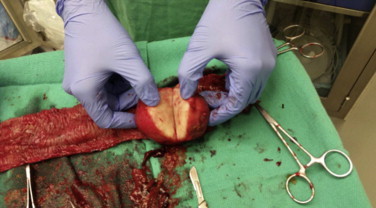

Fig. 6.

Gross morphology of the spindle cell tumor from case #9.

Fig. 7.

Intussusception of the small bowel segment from case #9.

1.2. Results

Abdominal pain was a common symptom, present in seven of nine cases. Seven of nine patients also complained of nausea. Abdominal pain and nausea occurred together in five cases. One third of our cases (3/9) involved intussusception of the colon while the other two thirds (6/9) involved segments of small bowel. Eight out of nine patients were taken to surgery 89% (8/9), with only 62.5% (5/8) of those cases requiring bowel resection. The other 37.5% (3/8) of patients were found to have resolution of intussusception at surgery. Laparoscopy aided surgical intervention in 50% (4/8) cases. One patient’s symptoms resolved with bowel rest alone and she was discharged home without surgical intervention (Table 1).

2. Presentation of cases

Table 1.

Summary table of the nine discussed cases.

| Age/sex | Important history | Presenting symptoms | Diagnosis | Type/location of lesion | Surgery/course of treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1a | 39/M | None |

|

Colocolonic intussusception | Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon near the left colic flexure |

|

Discharge after 4 days of recovery |

| Case 2a | 85/F | Addison’s disease |

|

Intussusception near the right colic flexure | Tubulovilous adenoma near the ileocecal valve | Right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastamosis | Uncomplicated recovery |

| Case 3 | 65/F | Melanoma |

|

Small bowel intussusception | Metastatic melanoma to the small bowel | Laparoscopic small bowel resection | Uncomplicated recovery |

| Case 4 | 21/M | Reflux |

|

Small bowel intussusception | Intussusception and volvulus of the small bowel | Exploratory laparotomy to confirm intussusception followed by small bowel resection | Uncomplicated recovery |

| Case 5 | 30/F | Obesity, cholecystitis, gastric bypass 2 years prior followed by a ventral hernia, and intussusception | Nausea, but no vomiting | Small bowel intussusception | Intra-pelvic | Twenty three hour observation in the hospital while kept n.p.o and on IV fluids | The obstruction resolved by the end of the observation period. |

| Case 6 | 20/M | IgA nephropathy and hypertension |

|

Small bowel intussusception | Distal jejunum | Diagnostic laparoscopy failed to identify any abnormalities | The patient’s intussusception resolved spontaneously just before surgery. |

| Case 7 | 25/F | Lupus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and lupus nephritis | Abdominal pain | Colocolonic intussusception | Mid-descending colon |

|

Uncomplicated recovery |

| Case 8 | 48/F | Congenital bowel malrotation |

|

Small bowel intussusception | Small bowel | Surgery to resect a possible mass found no intussusception | The patient’s intussusception resolved at the induction of anesthesia. Uneventful recovery. |

| Case 9a | 44/M | 30 Pounds of weight loss over the past 2 months | Nausea/vomiting | Small bowel intussusception | Inflammatory fibroid polyp as the lead point for intussusception | Diagnostic laparoscopy followed by resection of the affected bowel segment | Uncomplicated recovery |

Refer to corresponding Figure.

3. Discussion

Intussusception is essentially internal prolapse of the bowel with its mesenteric fold within the lumen of adjacent bowel as a result of impaired peristalsis. This phenomenon leads to obstruction, compromised mesenteric vascular flow, and ischemia [2,6]. The most common site for intussusception in adults is the small bowel, which is consistent with our findings of 66.6% (6/9) of cases involving small bowel [3]. About 90% of cases of adult intussusception have an identifiable pathologic lesion as a lead point. Intussusception can evolve from any pathologic lesion or irritant of the bowel wall that alters peristalsis [1,3].

Presentation varies considerably and symptoms are often non-specific and intermittent, rendering diagnosis somewhat difficult. In fact, only one-third of cases are diagnosed prior to surgery [3]. Abdominal pain is the most common presenting complaint, as seen in 78% [7/9] of our cases. Patients often complain of nausea, vomiting, constipation, bleeding per rectum, and diarrhea [2]. Abdominal pain concomitant with nausea should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of intussusception as demonstrated in 55% (5/9) of our cases, especially in the setting of de novo bowel obstruction. A palpable tender mass is a rare yet significant clinical manifestation [7]. In our experience, a palpable abdominal mass is admittedly easier to appreciate after induction of general anesthesia and muscle relaxants and is therefore, occasionally noted after the diagnosis has already been suggested by imaging modalities. Interestingly, the duration of symptoms appears to be longer in patients with benign and enteric lesions when compared to those with malignant and colonic lesions [5].

A number of radiologic methods are used in diagnosing intussusception including computed tomography (CT), plain X-ray, angiography, ultrasonography, and barium studies [5]. Plain X-ray is often used as the first diagnostic tool. Contrast studies may aid in determining the site and cause of intussusception by demonstrating the classic “stacked coin” or “coiled spring” sign [2]. Ultrasound typically presents the characteristic “target” or “donut” sign in the transverse view [7]. CT scan also demonstrates the “target” sign and was used to confirm the diagnosis of intussusception in 100% (9/9) of our cases. Ultimately, CT scan provides the premier means of defining the location and nature of the mass in addition to its relationship with surrounding tissues. Obesity and collected air in distended bowel segments can limit the quality of the CT images, preserving some of the mystery in making the diagnosis. Endoscopy is occasionally utilized when patients present with symptoms typical of large bowel obstruction. It was used in only 11% (1/9) of our cases. In fact, use of endoscopy as a diagnostic tool should be treated with caution as it carries a risk of perforation or reduction of potentially malignant intussusception [4,5]. Finally, confirmation of intussusception is often only achieved by laparoscopic or direct gross visualization in the operating room.

Our experience demonstrates that surgery continues to be the mainstay of treating adult intussusception. Laparoscopy was found to be a helpful adjunct to open surgical technique in select cases. The information gained from laparoscopy allowed us to tailor less invasive subsequent incisions for bowel resection and retrieval of the specimen. In case #6, diagnostic laparoscopy demonstrated resolution of intussusception and the patient was spared a non-therapeutic laparotomy incision as opposed to case #8.

Surgical management of intussusception in adults usually involves resection of affected bowel, sometimes preceded by manual reduction. Some controversy exists as to whether resection should proceed with or without reduction, for fear that inappropriate reduction of a malignant lesion may lead to intraluminal or venous seeding of malignant cells, perforation, and increased risk of complications [5]. Weilbaecher et al. suggests that all intussusceptions be treated by resection without reduction [5]. Eisen et al. supported this recommendation, stating that colonic lesions should not be reduced before resection because they are most likely primary adenocarcinomas [7]. When certain criteria are present, some authors advocate for reduction of small bowel intussusception prior to resection. Young patients with confirmed benign lesions, particularly those at risk for short bowel syndrome should be considered for such treatment [7]. Intussusception near the anal sphincter also warrants consideration of reduction prior to resection in order to avoid functional problems with regards to incontinence [5]. We reiterate that all cases must be examined on an individual basis given the possibility of embolizing malignant cells and upstaging a potentially curable cancer to stage four disease.

4. Conclusion

Surgeons should remain vigilant in evaluating the acute abdomen by approaching these patients with a broad differential. Although rare, adult intussusception should be considered in patients presenting with concomitant abdominal pain and emesis, especially in the setting of a tender palpable abdominal mass and/or de novo bowel obstruction. CT scan carries a strong positive predictive value for distinguishing intussusception from other forms of bowel obstruction, marked by the pathognomonic target sign. In trained hands, laparoscopy has proven to be an excellent adjunct to open surgical technique. Reduction of intussusception before resection remains controversial and should be decided on a case to case basis with a predilection for young patients with confirmed benign lesions [5–7].

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests.

Funding

The Surgery Residency Program at San Joaquin General Hospital provided the funds needed for submission.

Ethical approval

IRB committee approval was obtained by Dr. Pratik Mehta.

Author contribution

Pratik Mehta – Concepts, definition of intellectual content, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript editing, and manuscript review.

Alex Darwish – Design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review.

Amr El-Sergany – Concepts, definition of intellectual content, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript editing, and manuscript review.

Ahmed Mahmoud – Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, data analysis, manuscript editing, manuscript review.

Guarantor

Ahmed Mahmoud.

Contributor Information

Amr El-Sergany, Email: ael-sergany@sjgh.org.

Alex Darwish, Email: alex.darwish.2009@gmail.com.

Pratik Mehta, Email: mehpr20@gmail.com.

Ahmed Mahmoud, Email: ahmedmahmoud5@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Azar T., Berger D.L. Adult intussusception. Ann. Surg. 1997;226:134–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zubaidi A., Al-Saif F., Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1546–1551. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A., Gupta S., Tandon A., Kotru M., Kumar S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor causing ileo-ileal intussusception in an adult patient a rare presentation with review of literature. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2011;8 doi: 10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagorney D.M., Sarr M.G., McIlrath D.C. Surgical management of intussusception in the adult. Ann. Surg. 1981;193:230–236. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198102000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yalamarthi S., Smith R.C. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005;81:174–177. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.022749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang N., Cui X.Y., Liu Y., Long J., Xu Y.H., Guo R.X., Guo K.J. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review of 41 cases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3303–3308. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi K., Tsuzuki Y., Ando T., Sekihara M., Hara T., Kori T., Kuwano H. The diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003;36:18–21. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]