Abstract

Engineering a safe and high-efficiency delivery system for efficient RNA interference is critical for successful gene therapy. In this study, we designed a novel nanocarrier system of polyethyleneimine (PEI)-modified Fe3O4@SiO2, which allows high efficient loading of VEGF small hairpin (sh)RNA to form Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites for VEGF gene silencing as well as magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. The size, morphology, particle stability, magnetic properties, and gene-binding capacity and protection were determined. Low cytotoxicity and hemolyticity against human red blood cells showed the excellent biocompatibility of the multifunctional nanocomposites, and also no significant coagulation was observed. The nanocomposites maintain their superparamagnetic property at room temperature and no appreciable change in magnetism, even after PEI modification. The qualitative and quantitative analysis of cellular internalization into MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by Prussian blue staining and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy analysis, respectively, demonstrated that the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites could be easily internalized by MCF-7 cells, and they exhibited significant inhibition of VEGF gene expression. Furthermore, the MR cellular images showed that the superparamagnetic iron oxide core of our Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites could also act as a T2-weighted contrast agent for cancer MR imaging. Our data highlight multifunctional Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites as a potential platform for simultaneous gene delivery and MR cell imaging, which are promising as theranostic agents for cancer treatment and diagnosis in the future.

Keywords: core/shell nanoparticle, PEI, VEGF silence, MR imaging, theranostics

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi), a process characterized by sequence-specific, post-transcriptional gene silencing directed by short interfering 21–23 nucleotide double-stranded RNA (small interfering [si]RNA) can specifically and markedly reduce the expression of targeted messenger (m)RNA. RNAi represents a novel way to treat diseases that use double-stranded RNAs that undertake the function of regulating gene expression without any permanent effect on the genome.1,2 However, although siRNA interference is valid, a safe and efficient delivery vector is still a major hurdle to the further development of RNAi therapeutics because of its large molecular weight, strong negative charge, and instability under nuclease and serum proteins, as well as its low transfection efficiency.3,4 In recent years, interest has grown in developing effective transport carriers to overcome these disadvantages. Due to the fact that they possess intrinsic properties, such as a high surface area, good biocompatibility, and easy surface modification, and given that they facilitate gene attachment, magnetic silica nanoparticles can be used as an excellent carrier for gene delivery.5–8 Although magnetic silica nanoparticles are considered to be a favorable gene carrier, it is especially important to increase the gene-binding capacity.5 The magnetic silica nanoparticles are further coated with a cationic polymer such as poly (allylamine hydrochloride) or polyethyleneimine (PEI), which can help in conjugation with siRNA.9,10 PEI, which contains primary, secondary, and tertiary amines to complex with nucleic acids such as DNA or siRNA, can protect the siRNA from degradation in vivo and facilitate subsequent siRNA release from endosomes due to the proton sponge effect. Currently, PEI is one of the most widely studied cationic polymers for gene delivery.11–13 In addition, PEI can also be easily modified by coupling some small molecules to endow it specific targeting ability.14 Although high-molecular-weight PEI of 25 kD has high transfection efficiency, it has relative cytotoxicity and causes nonspecific binding with serum proteins. Low-molecular-weight PEI, such as PEI-600 Da has low cytotoxicity, but it shows very low transfection efficiency.15–17 In this regard, it has been demonstrated that the size (molecular weight), compactness, and chemical modification of PEI affect the efficacy and toxicity of this polymer. Xia et al used several PEI polymer sizes ranging from molecular weights of 0.6–25 kD in order to balance the efficiency of nucleic acid delivery and cellular toxicity.18–20 They demonstrated that the hybrid organic–inorganic nanoparticles with optimal polymer lengths can maintain high transfection efficiency, while simultaneously reducing or eliminating toxic effects.

Angiogenesis (also known as neovascularization) is defined as the development of new blood vessels from preexisting vessels, and it is an attractive target for cancer therapy because it is essential for tumor growth and hematogenous metastasis.21,22 Growth and survival of tumors depends on the tumor vessels being able to supply oxygen and nutrient substances. Tumors can only reach a size of 1–2 mm3 without angiogenesis. VEGF is a positive and potent regulator of angiogenesis. The inhibition of VEGF expression by siRNA has been considered key to the treatment of cancer, and was reported to be an effective and useful method for antiangiogenic tumor therapy in vitro and in vivo.23,24

In recent years, there is great hope and expectation in the development of theranostic nanocarriers, which combine diagnostic and therapeutic agents in one entity.25–27 Diagnostic and therapeutic agents are physically entrapped or conjugated to the nanocarriers, or they are conjugated to carefully designed polymers, which subsequently form nanocarriers.28,29 In the present study, PEI-modified core/shell nanoparticles of Fe3O4@SiO2 were fabricated, which could electrostatically absorb VEGF small hairpin (sh)RNA. The Fe3O4@SiO2/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites showed low cytotoxicity and good hemocompatibility, and they could be easily internalized by MCF-7 cells; they also exhibited significant inhibition of VEGF gene expression. A significant knockdown efficiency has been shown when the concentration of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI reached 60 μg/mL, but cytotoxicity was not obviously detected. We also demonstrated that the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites had the potential for VEGF shRNA delivery and MR imaging simultaneously.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimetho-xysilane (AEAP3), and branched PEI (25 kD) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Iron oxide nanoparticles (10 nm) were obtained from Nanjing Emperor Nano Material Co. Ltd. (Nanjing, People’s Republic of China). Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 cell culture medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and trypsin were purchased from Gibco® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All the chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites

The Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by a modified method, as described in previous work.30–32 In brief, Fe3O4 nanoparticles (10 nm) were dispersed into a mixture containing 0.78 mL of Milli-Q water, 3.6 mL of Triton X-100, 3.2 mL of anhydrous 1-hexanol, and 14 mL of cyclohexane, and then stirred vigorously at room temperature. Following a 1-hour reaction, 0.34 mL of ammonia solution (28%–30%) was added into the aforementioned mixture and stirred for another hour. Finally, TEOS (50 μL) was added with stirring for 24 hours, followed by the addition of AEAP3 with continuous stirring for another 24 hours. The resulting product was separated by high-speed centrifugation, and washed with ethanol and distilled water three times.

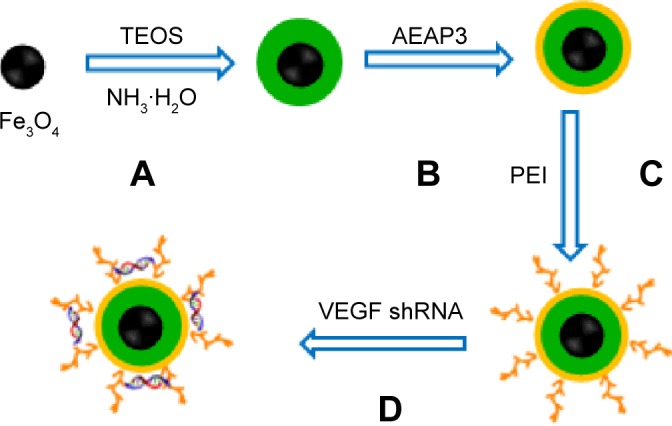

PEI was coated on the surfaces of the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles through electrostatic interaction. Briefly, PEI solution (20 mg/mL) was added into the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticle suspension (5 mg/mL), which was then mixed by stirring for 2 hours to allow PEI to graft onto the surfaces of the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles. Unbound PEI was removed by centrifugation with deionized water three times. The PEI-functionalized Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles were harvested by centrifugation and washed five times with distilled water to remove excess reactants. VEGF shRNA was incubated in the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticle suspension for 30 minutes at room temperature to form Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites by electrostatic absorption at various weight ratios. The synthetic procedure for the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites for gene delivery.

Notes: (A) Hydrolyzing TEOS to form the first silica shell; (B) hydrolyzing AEAP3 to form the second silica shell. (C) Coating PEI on the surface of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI); (D) binding of VEGF shRNA to Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI by electrostatic interaction (Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA).

Abbreviations: TEOS, tetraethylorthosilicate; AEAP3, N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-amino-propyltrimetho-xysilane; PEI, polyethylenimine; shRNA, small hairpin RNA.

Characterization

The size and morphology of the nanoparticles were obtained via scanning electron microscopy (Helios NanoLab 650; FEI, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). The microstructure and composition of the samples were characterized by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, scan transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and selected area electron diffraction on a Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN (200 kV) high-revolution transmission electron microscope. Magnetic measurements of samples were performed with a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer (MPMS-5S; Quantum Design, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For measurement, about 10 mg of powder samples was inserted in a gelatin capsule. The magnetic hysteresis loop was measured at room temperature. The zeta-potentials for various pH values were measured using electrophoretic mobility measurements (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

Hemolysis assay

The hemolysis assay experiments were carried out according to previous reports with minor modifications.33–35 Blood from healthy Sprague Dawley rats was collected in heparin-coated tubes. The red blood cells (RBCs) were obtained by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes, and the upper plasma was removed. The RBCs were then washed with sterile isotonic 0.9% NaCl solution three times. The purified RBCs were resuspended with sterile isotonic 0.9% NaCl. The RBC suspension (300 mL) was mixed with 1.2 mL of 5 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, 20 μg/mL, 40 μg/mL, or 80 μg/mL of the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticle suspension. Distilled water and sterile isotonic 0.9% NaCl were used as the positive and negative control, respectively. All the samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours, and then centrifuged for 2 minutes at 4,000 rpm. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 541 nm using ultraviolet (UV)–visible spectroscopy (UV-2910; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). We could calculate the hemolysis by the equation below:

| (1) |

Stability of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites

The stability of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites was investigated by recording the turbidity change in 50% FBS. A total of 150 μL of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI or Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA suspension (VEGF shRNA =100 μg/mL) was added to an equivalent volume of FBS in 96-well plates and incubated for various times up to 72 hours at 37°C. The turbidity of the nanocomposites in serum was measured by the absorbance values at a 415 nm wavelength on a microplate reader (ELx808™; BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at different time points. The glucose (5%) solution was used as a negative control.

Agarose gel electrophoresis retardation assay

To test the absorption ability of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles to VEGF shRNA, agarose gel electrophoresis retardation assay was used. VEGF shRNA was incubated in the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticle suspension for 30 minutes at room temperature to form Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites by electrostatic absorption at various weight ratios from 5:1 up to 40:1. The Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites were sampled for electrophoresis on the 1% agarose gel with tris/acetate/EDTA buffer at 120 V for 25 minutes, and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The VEGF DNA bands were acquired and visualized using a UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell viability

The cytotoxicity of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles was evaluated by CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution (MTS) assay (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5×103 cells per well and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 hours. After removing the culture medium, cells were given fresh complete culture medium and treated with different concentrations of Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@ SiO2/PEI, Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/scrambled shRNA (denoted as Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA) in triplicate at each concentration for 72 hours. Wells containing culture medium alone were used as the blank control. The absorbance of the solution was recorded at 490 nm using a microplate reader (ELx808™; BioTek Instruments, Inc.). The relative cell viability could be quantitatively calculated by the following equation:

| (2) |

A490 is the absorbency at 490 nm wavelength.

Uptake of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA by MCF-7 cells

The cellular uptake of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites into MCF-7 human breast cancer cells was examined by Prussian blue staining and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) analyses. Briefly, MCF-7 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 3×104 and incubated for 24 hours. The Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites were prepared at a ratio of 40:1 (the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI to VEGF shRNA weight ratio), and the concentrations of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI were from 5–80 μg/mL. After 24 hours of incubation in complete cell culture medium, the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for a total of five times, fixed with paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, and then incubated with a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of potassium ferrocyanide and hydrochloric acid for 15 minutes. Finally, the cells were washed again with PBS, then observed under a microscope (TE-2000U; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The amount of iron in the MCF-7 cells was detected by ICP-OES. After incubation with Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites at different concentrations for 24 hours, the cells were washed with PBS five times, and then dissolved in nitric acid. The concentration of Fe was quantitatively measured by ICP-OES.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay

MCF-7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates until the density reached approximately 60%. Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI, Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA, or Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA was incubated with the cells in serum-free medium for 6 hours, and then replaced with complete cell culture medium. For the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis, the total messenger (m)RNA from MCF-7 cells was obtained using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One milligram of total mRNA was transcribed into complementary DNA using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Dalian, People’s Republic of China.). All qPCR were performed using the Faststart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX), and the amplification threshold (Ct) of each gene was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The comparative Ct method was used to calculate the fold changes. Efficiency for all primer pairs was 95%–100%. Primer pairs used were VEGF (forward, 5′-TTCTCAAGGACCACCGCATC-3′; reverse, 5′-AATGGGGTCGTCATCTGGT-3′), and GAPDH (forward, 5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′; reverse, 5′-ACCACCCTGTTG CTGTAGCCAA-3′).

ELISA assay

The VEGF secretion protein level was evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).9 Briefly, cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at cell density of 3×104 cells/well overnight and transfected with various nanocomposites, similar to the procedures in the qPCR assay. The culture medium was collected 72 hours post-transfection, followed by centrifugation at 5,000 ×g for 10 minutes. The VEGF concentrations in the supernatants were detected by a human VEGF ELISA kit (Neobioscience, Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All of the assays were performed in triplicate.

Cellular MR imaging

Fe3O4 nanoparticles can be used as a T2 weighted-negative contrast agent in magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, due to the fact that Fe3O4 nanocrystals have superparamagnetic characteristics and can shorten the transverse relaxation of water protons.25,33 T2 weighted-MR signals of the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA in MCF-7 cells under different nanocomposite concentrations were measured. MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 3×105 cells per well on six-well plates in 2 mL of media and grown overnight. After removing the culture medium, the fresh complete culture medium containing Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA of various concentrations (5–80 μg/mL) was added. After 24 hours, the cells were washed three times with PBS to remove noninternalized nanocomposites, which were detached by the addition of 0.8 mL of trypsin/EDTA. After centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes, cells were suspended in 500 μL of 1% agarose. Furthermore, MR imaging was performed at 25°C in a clinical 3.0 Tesla Clinical Siemens Trio scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The differences were considered significant for a P-value <0.05, and P<0.01 was indicative of a very significant difference.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles

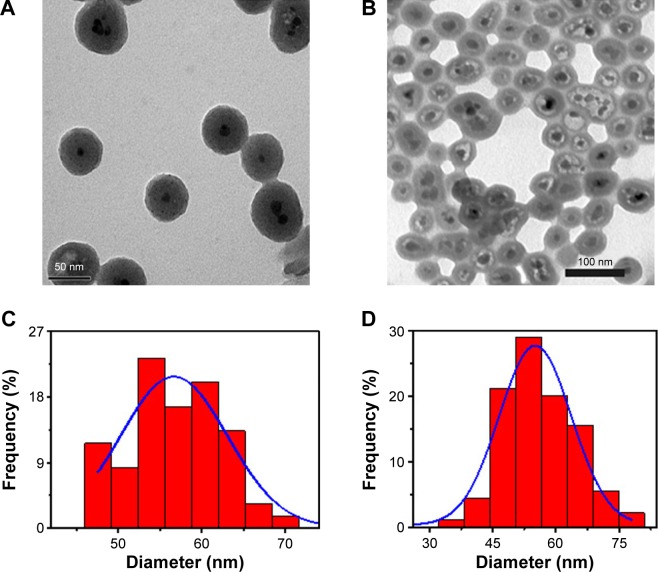

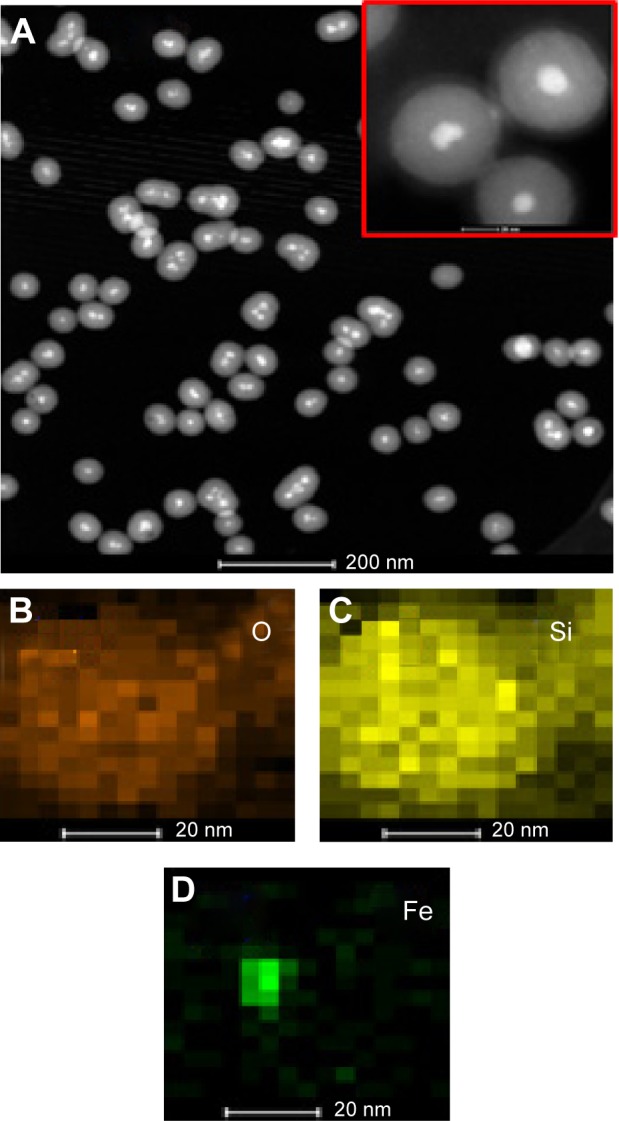

The multistep processes for fabrication of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites are shown in Figure 1, which is similar to previously reported processes with minor modifications.9 The Fe3O4 nanoparticles were coated with a silica shell to form core/shell structural Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles.31,32 PEI was coated on the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticle surfaces by electrostatic interaction to enhance targeted gene adsorption and transfection efficiency. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and STEM were used to characterize the structure and morphology of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites. The TEM images confirmed that both Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles (Figure 2A) and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites (Figure 2B) were uniform, spherical, and well dispersed in suspension (Figure 2C and 2D). A clear core/shell structure was observed for Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles with a mean diameter of 57 nm. Of interest, the mean diameter and average shell thickness of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites did not change in an obvious manner, even after PEI modification and VEGF shRNA absorption. This suggests that PEI modification and VEGF shRNA complexation did not affect the morphology and size distribution of the nanoparticles. This core/shell structure was also clearly confirmed by the STEM image of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles (Figure 3A). Compositional analysis of the nanocomposite was carried out using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping (Figure 3B–D); the signals for the oxygen, silica, and iron elements were clearly detected in the nanoparticles. All of the aforementioned data demonstrated that core/shell structural Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites could be successfully obtained by our modified method.

Figure 2.

Morphology of Fe3O4@SiO2 and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites.

Notes: TEM images of (A) Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles and (B) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites. Size distribution histograms of (C) Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles and (D) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites.

Abbreviations: PEI, polyethylenimine; shRNA, small hairpin RNA; TEM, transmission electron microscope.

Figure 3.

STEM and HAADF-STEM-EDS mapping images of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles O, Si, and Fe.

Notes: (A) STEM of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles (inset: higher-magnification image of STEM). (B–D) HAADF-STEM-EDS mapping images of Fe3O4@SiO2 revealing the O, Si, and Fe.

Abbreviations: STEM, scanning transmission electron microscope; HAADF-STEM-EDS, high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy–energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry; O, oxygen; Si, silica; Fe, iron.

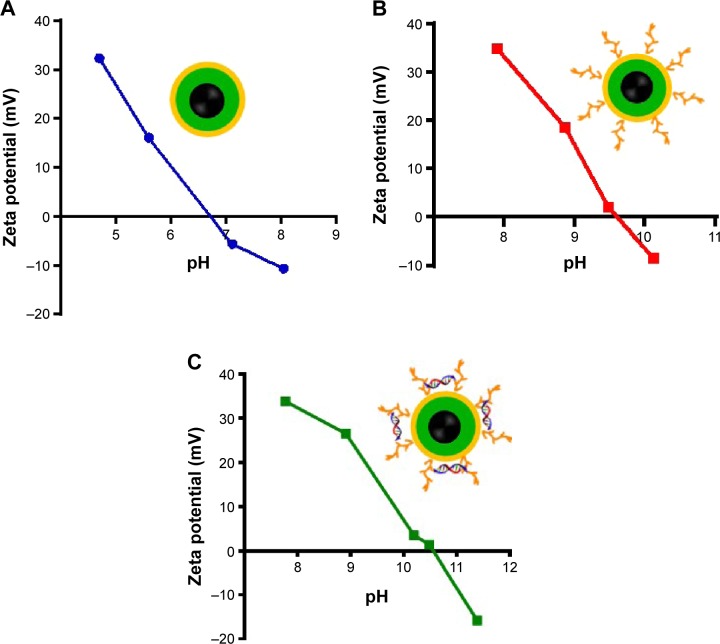

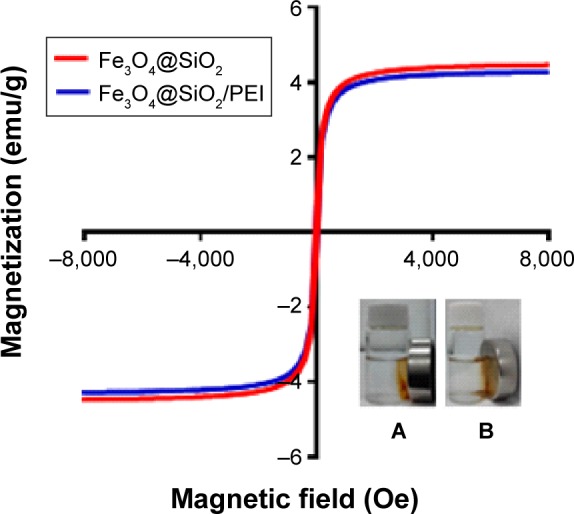

Figure 4 shows the zeta-potential titrations as a function of pH for Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI, and Fe3O4@ SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites. It was found that isoelectric points for Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites were increased to 9.7 and 10.5, respectively. The isoelectric points were increased as modified with polymer, and the shift of the isoelectric points indicated that the PEI modification and VEGF shRNA electrostatical absorption were successful.36–38 For the assessment of the magnetic properties and the sensitivity of the formulated nanoparticles, magnetic hysteresis loops were recorded using a magnetometer, and the two types of nanoparticles showed superparamagnetic behavior without magnetic hysteresis (Figure 5) at room temperature (about 300 K). PEI modification did not change the magnetic property of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles. Their magnetization saturation value was ~4.4 emu/g, and no significant difference in the magnetization saturation value was observed for the Fe3O4@SiO2 and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles. Furthermore, the magnetic targeting of nanoparticles was tested in water by placing a magnet near the glass bottle. Both the Fe3O4@SiO2 and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI were attracted toward the magnet within a very short period of time (Figure 5, inset). These data revealed their superparamagnetic nature, and the nanoparticles could also get to targeted locations under an external magnetic field.

Figure 4.

Zeta-potentials in various pH values for the nanoparticles.

Notes: (A) Fe3O4@SiO2; (B) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI; and (C) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: PEI, polyethylenimine; shRNA, small hairpin RNA.

Figure 5.

Magnetization curves of Fe3O4@SiO2 and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI measured at room temperature.

Notes: Inset: magnetic targeting under an external magnet, (A) Fe3O4@SiO2 and (B) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI.

Abbreviation: PEI, polyethylenimine.

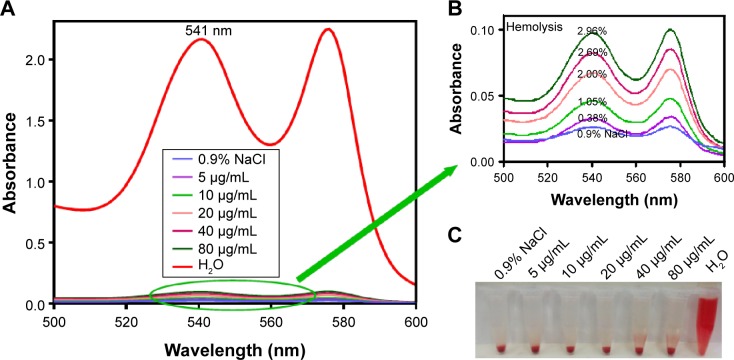

Hemolysis and stability assay of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles

It is essential to investigate the hemocompatibility of nanocarriers for their successful systemic administration.33,34 Therefore, the hemolysis experiment for Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI was carried out to evaluate the impacts of the nanocarriers on RBCs. As show in Figure 6, almost no hemolysis of the RBCs could be detected at the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI concentrations from 5–80 μg/mL, and only ~2.96% of hemolysis activity was detected at the high concentration of 80 μg/mL. These results indicated that Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanocarriers have negligible hemolysis activity and could further be injected intravenously.

Figure 6.

Hemolysis assay for the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles. (A) Hemolysis detection by UV-vis spectrophotometer; (B) Mignifation of the circle indicated; (C) Photo of hemolysis at various concentrations of nanoparticles.

Notes: The bottom-right inset is the photo of the direct observation of hemolysis by Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI at different concentrations; 0.9% NaCl is the negative control and H2O is the positive control.

Abbreviation: PEI, polyethylenimine.

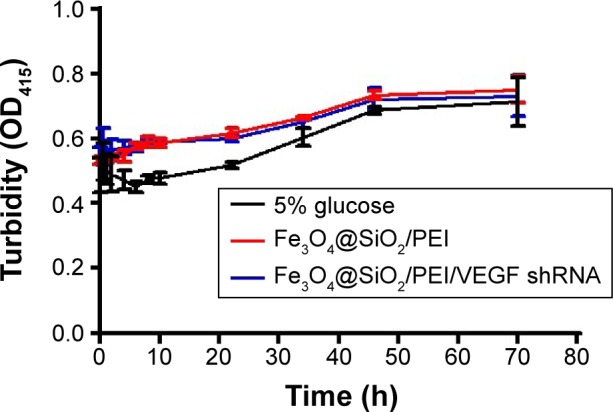

It is well known that PEI has a high positive potential. However, the nonspecific interaction between the positively charged nanocomposites and the negatively charged serum proteins could lead to the loss of treatment efficiency, which is a serious safety issue.39,40 Here, we measured the changes of turbidity to assess the stability of nanocomposites in serum. As shown in Figure 7, no significant increase of turbidity was found in various nanocarrier suspensions after incubated in serum for 72 hours, as well as that of 5% glucose. It is suggested that the PEI-modified nanoparticles cannot increase the aggregation caused by nonspecific interactions with serum proteins. Taken together, the aforementioned data demonstrated that the fabricated nanocarriers exhibited excellent biocompatibility.

Figure 7.

The stabilities of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles in fetal bovine serum.

Note: Five percent glucose was used as the negative control.

Abbreviations: PEI, polyethylenimine; shRNA, small hairpin RNA; h, hours.

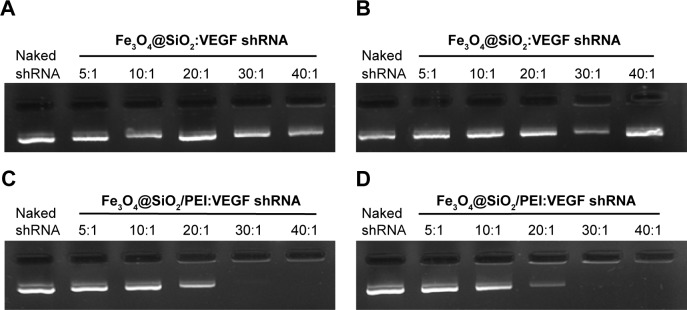

Binding capacity and cytotoxicity assay of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles

The nuclear acid-binding capability of the nanoparticles is a very important factor to consider when choosing a gene delivery carrier.41,42 The binding capacity to VEGF shRNA was further analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, as shown in Figure 8. It was found that Fe3O4@SiO2 cannot bind VEGF shRNA, neither in deionized water nor in 0.9% NaCl solution (Figure 8A and B). This is due to the fact that both Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles and DNA presented negative potential. However, for the same weight of nanoparticles, the surface charge is significantly higher after coating with PEI, which would provide a high adsorption capacity. As shown in Figure 8C, at different weight ratios from 5:1–40:1, the binding capability of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI to VEGF shRNA enhanced with the weight ratio, and it increased in deionized water. When the weight ratio was over 30:1, almost all the VEGF shRNA was restrained with the nanocomposites. Consistent results were obtained when Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA was incubated in 0.9% NaCl solution (Figure 8D). These data indicated that Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles were capable of effectively binding VEGF shRNA, and could be employed as a gene delivery carrier.

Figure 8.

Agarose gel electrophoresis retardation assays.

Notes: (A) Fe3O4@SiO2:VEGF shRNA and (C) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI:VEGF shRNA at different weight ratios (5:1, 10:1, 20:1, 30:1, and 40:1) in water; and (B) Fe3O4@SiO2:VEGF shRNA and (D) Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI:VEGF shRNA at different weight ratios (5:1, 10:1, 20:1, 30:1, and 40:1) in 0.9% NaCl.

Abbreviations: shRNA, small hairpin RNA; PEI, polyethylenimine.

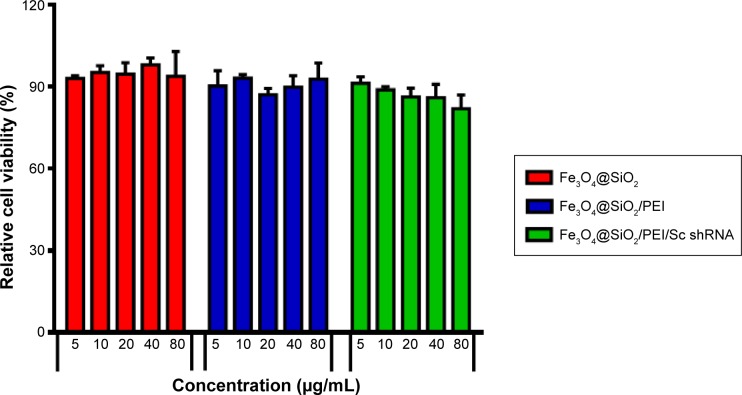

For the ultimate use of nanoparticles as a gene carrier, it is critical that these nanoparticles, after being coated with silica and PEI, retain their low toxicity – ie, the gene carrier should not induce cytotoxic effects.43–45 In order to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the resulting nanoparticles, the viability of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells was tested by MTS assay in the presence of Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI, or Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA. As shown in Figure 9, Fe3O4@ SiO2 nanoparticles did not exhibit any detectable cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells, even after being incubated with a high concentration of nanoparticles for 72 hours. More than 85% of the cells remained viable after incubation with Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA in concentrations of 5–80 μg/mL. This suggests that the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI nanoparticles showed no significant cytotoxicity, and that they could be used as a carrier for gene therapy.

Figure 9.

Evaluating the toxicity of different nanovectors incubated with MCF-7 for 72 hours.

Note: The dose of nanovectors ranges from 5–80 μg/mL.

Abbreviations: PEI, polyethylenimine; Sc, scrambled; shRNA, small hairpin RNA.

Cellular uptake of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites

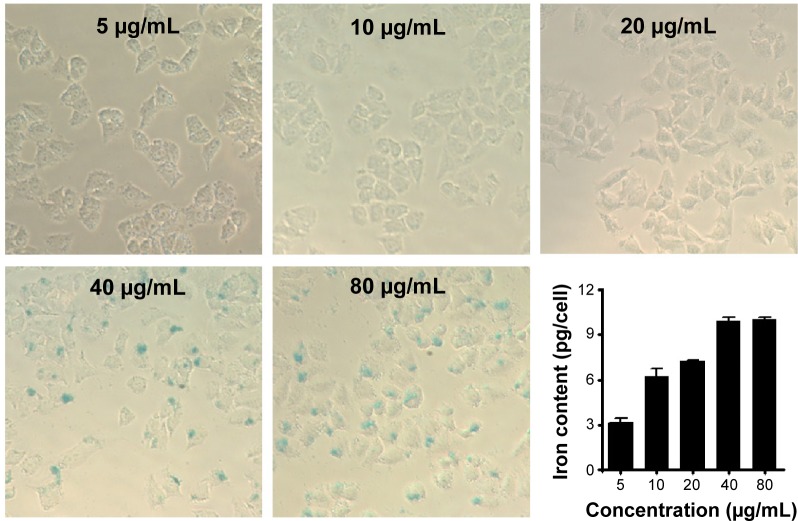

Prussian blue staining and ICP-OES analysis were conducted to determine whether the functionalized core/shell nanocomposites could be delivered into the MCF-7 cells in vitro (Figure 10). Blue-stained iron can be clearly observed under microscope at high nanocomposite concentrations. These data illustrated that the cellular uptake level strongly depended on the concentration of the nanocomposites. Few blue-stained irons were observed in the low nanocomposite concentrations of 5–20 μg/mL, but ICP-OES could quantitatively detect the presence of iron in the MCF-7 cells. It may be that a small amount of nanocomposites were internalized by MCF-7 cells, and the iron concentrations were too low to be stained into blue. A much stronger blue appearance emerged when the concentrations of nanocomposites reached up to 40 μg/mL or 80 μg/mL. The quantitative results by ICP-OES analysis agreed well with the qualitative data by microscope.

Figure 10.

Microscope images of Prussian blue dye staining of MCF-7 cells after 24 hours of incubation at concentrations of 5 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, 20 μg/mL, 40 μg/mL and 80 μg/mL, respectively.

Notes: The iron in the cells was stained blue and the Fe–iron accumulation in MCF-7 cells was detected by ICP-OES analysis shown in the bottom-right image.

Abbreviation: ICP-OES, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy.

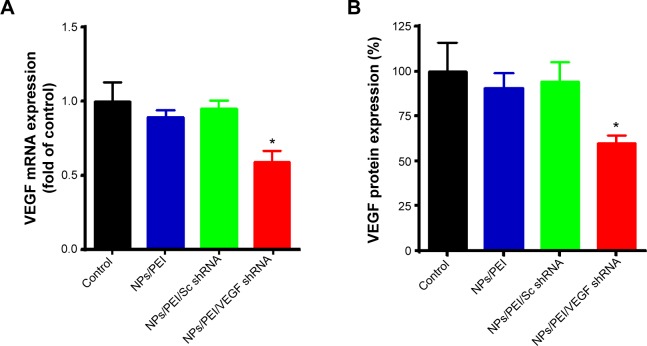

Gene silencing efficiency of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites

RNAi uses double-stranded ribonucleic acids to undertake the function of regulating gene expression.46 In this study, the gene silencing efficiency of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA after 72 hours of incubation was evaluated by qPCR and ELISA assays in mRNA, as were the protein levels in MCF-7 cells, respectively (Figure 11). As compared to control and Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA, Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA could significantly inhibit VEGF mRNA expression and enhanced the gene silencing efficiency (Figure 11A). The high gene silencing efficiency of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites was further supported by the reducing VEGF expression in the protein levels. ELISA analysis showed that Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites dramatically downregulated the VEGF secretion compared to control or Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA (Figure 11B). These results suggest that the Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites could silence VEGF expression in a highly sequence-specific fashion.

Figure 11.

Detection of VEGF expression.

Notes: (A) Suppression of VEGF mRNA levels determined by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) The secretion of VEGF protein in culture media tested by human VEGF ELISA kit; both of the experiments were executed at 72 hours after transfection with Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI (NPs/PEI), Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/Sc shRNA (NPs/PEI/Sc shRNA), or Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA (NPs/PEI/VEGF shRNA). All the NP concentrations are 60 μg/mL. For the NPs/PEI/Sc shRNA and NPs/PEI/VEGF shRNA, the weight ratio of NPs/PEI to Sc shRNA or VEGF shRNA is 40:1. *P<0.05 compared with NPs/PEI or NPs/PEI/Sc shRNA.

Abbreviations: mRNA, messenger RNA; NPs, nanoparticles; PEI, polyethylenimine; Sc, scrambled; shRNA, small hairpin RNA; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

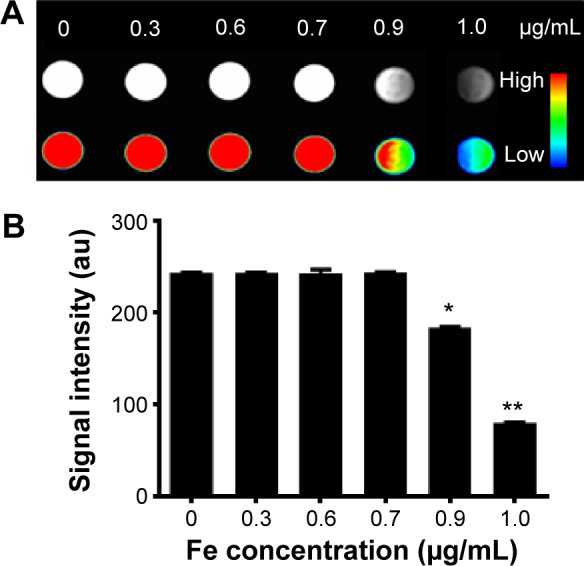

Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites as contrast agents for MR cellular imaging

To evaluate the potential of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites for use as a MR contrast agent, MCF-7 cells were cultured with various concentrations of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites, as described in the Materials and methods. T2-weighted MR images of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposite-labeled cell phantom were acquired (Figure 12A). As the concentrations of the iron increased during the incubation, the T2-weighted MR image was darkened. At the high Fe concentrations of 0.9 μg/mL and 1.0 μg/mL, the T2-weighted MR images were darker than those at the low concentration samples in MCF-7 cells. Figure 12B shows that the MR signal intensity decreased with the Fe concentration in MCF-7 cells, which was also consistent with the T2-weighted MR images.

Figure 12.

T2-weighted MR images and quantitative signal intensity analysis of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA.

Notes: (A) T2-weighted MR images and color T2-weighted MR images of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA. The weight ratio of Fe3O4@SiO2/PEI to VEGF shRNA is 40:1. (The color bar from red to blue shows the gradual decrease of MR signal intensity.) (B) Quantitative signal intensity analysis. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with the control (0 μg/mL).

Abbreviations: MR, magnetic resonance; PEI, polyethylenimine; shRNA, small hairpin RNA.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a facile VEGF shRNA delivery vector based on magnetic silica nanoparticles and PEI. The PEI polymer was coated on the surface of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles, followed by electrostatic adsorption of VEGF shRNA. The Fe3O4/SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites exhibited negligible hemolysis against human blood, and very low cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. Such vectors could be readily internalized into cells and showed significant downregulation of VEGF expression at both the mRNA and protein level in MCF-7 cells. We also revealed that the Fe3O4/SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites were able to be used as an efficient nanoprobe for the MR imaging of cancer cells. Taken together, Fe3O4/SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposites simultaneously possess dual functions for gene delivery and cellular imaging. Although the in vivo data should be further investigated, based on the in vitro data and findings, the Fe3O4/SiO2/PEI/VEGF shRNA nanocomposite is still a good candidate as a theranostic agent, and has high potential in future medical applications.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge financial support, in whole or in part, provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (numbers 81201192, 81101147, 31470959, 81471785, 11272083, and 31470906), the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Foundation of China (numbers 2014JQ0008, 2010JQ0004), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2011M501406), and the China Postdoctoral Science Special Foundation (2012T50773). We would also like to thank Xuefeng Zhang from the National Research Council of Canada for his assistance in the experiments.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gandhi NS, Tekade RK, Chougule MB. Nanocarrier mediated delivery of siRNA/miRNA in combination with chemotherapeutic agents for cancer therapy: current progress and advances. J Control Release. 2014;194:238–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong DW, Xiang B, Gao W, Yang ZZ, Li JQ, Qi XR. pH-responsive complexes using prefunctionalized polymers for synchronous delivery of doxorubicin and siRNA to cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(20):4849–4859. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han L, Zhao J, Zhang X, et al. Enhanced siRNA delivery and silencing gold-chitosan nanosystem with surface charge-reversal polymer assembly and good biocompatibility. ACS Nano. 2012;6(8):7340–7351. doi: 10.1021/nn3024688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang H, Li Y, Li T, et al. Multifunctional core/shell nanoparticles cross-linked polyetherimide-folic acid as efficient Notch-1 siRNA carrier for targeted killing of breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7072. doi: 10.1038/srep07072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X, Zhao Y, Ng KW, Zhao Y. Integrated hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles for target drug/siRNA co-delivery. Chemistry. 2013;19(46):15593–15603. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Chen Y, Wang M, Ma Y, Xia W, Gu H. A mesoporous silica nanoparticle – PEI – fusogenic peptide system for siRNA delivery in cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2013;34(4):1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin D, Cheng Q, Jiang Q, et al. Intracellular cleavable poly(2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for efficient siRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale. 2013;5(10):4291–4301. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00294b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng H, Mai WX, Zhang H, et al. Codelivery of an optimal drug/siRNA combination using mesoporous silica nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance in breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. ACS Nano. 2013;7(2):994–1005. doi: 10.1021/nn3044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Shi M, Xu M, Yang H, Wu C. Multifunctional nanoparticles of Fe(3)O(4)@SiO(2)(FITC)/PAH conjugated the recombinant plasmid of pIRSE2-EGFP/VEGF(165) with dual functions for gene delivery and cellular imaging. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9(10):1197–1207. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.709845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Gu H, Zhang DS, Li F, Liu T, Xia W. Highly effective inhibition of lung cancer growth and metastasis by systemic delivery of siRNA via multimodal mesoporous silica-based nanocarrier. Biomaterials. 2014;35(38):10058–10069. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, et al. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akinc A, Thomas M, Klibanov AM, Langer R. Exploring polyethylenimine-mediated DNA transfection and the proton sponge hypothesis. J Gene Med. 2005;7(5):657–663. doi: 10.1002/jgm.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S, May S. Release of cationic polymer-DNA complexes from the endosome: A theoretical investigation of the proton sponge hypothesis. J Chem Phys. 2008;129(18):185105. doi: 10.1063/1.3009263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Fan Y, Wu Y. Inositol based non-viral vectors for transgene expression in human cervical carcinoma and hepatoma cell lines. Biomaterials. 2014;35(6):2039–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li JM, Wang YY, Zhang W, Su H, Ji LN, Mao ZW. Low-weight polyethylenimine cross-linked 2-hydroxypopyl-β-cyclodextrin and folic acid as an efficient and nontoxic siRNA carrier for gene silencing and tumor inhibition by VEGF siRNA. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:2101–2117. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S42440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Zheng M, Meng F, Zhang J, Peng R, Zhong Z. Branched polyethylenimine derivatives with reductively cleavable periphery for safe and efficient in vitro gene transfer. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(4):1032–1040. doi: 10.1021/bm101364f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Chen Z, Li Y. Dual-degradable disulfide-containing PEI-Pluronic/DNA polyplexes: transfection efficiency and balancing protection and DNA release. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:3689–3701. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S49595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florea BI, Meaney C, Junginger HE, Borchard G. Transfection efficiency and toxicity of polyethylenimine in differentiated Calu-3 and nondifferentiated COS-1 cell cultures. AAPS Pharm Sci. 2002;4(3):E12. doi: 10.1208/ps040312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, et al. Polyethyleneimine coating enhances the cellular uptake of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and allows safe delivery of siRNA and DNA constructs. ACS Nano. 2009;3(10):3273–3286. doi: 10.1021/nn900918w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neu M, Fischer D, Kissel T. Recent advances in rational gene transfer vector design based on poly(ethylene imine) and its derivatives. J Gene Med. 2005;7(8):992–1009. doi: 10.1002/jgm.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo DH, Kim JH, Yu YS, Lee TG, Kim JH. Antiangiogenic effect of silicate nanoparticle on retinal neovascularization induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Nanomedicine. 2012;8(5):784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao X, Zhu DM, Gan WJ, et al. Lentivirus-mediated shRNA interference targeting vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits angiogenesis and progression of human pancreatic carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(3):1019–1026. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Zhang WJ, Xiu B, et al. Nanocomposite-siRNA approach for down-regulation of VEGF and its receptor in myeloid leukemia cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;63:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang S, Shao K, Liu Y, et al. Tumor-targeting and microenvironment-responsive smart nanoparticles for combination therapy of antiangiogenesis and apoptosis. ACS Nano. 2013;7(3):2860–2871. doi: 10.1021/nn400548g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JE, Lee N, Kim H, et al. Uniform mesoporous dye-doped silica nanoparticles decorated with multiple magnetite nanocrystals for simultaneous enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, fluorescence imaging, and drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(2):552–557. doi: 10.1021/ja905793q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F, Chen X, Zhao Z, et al. Synthesis of magnetic, fluorescent and mesoporous core-shell-structured nanoparticles for imaging, targeting and photodynamic therapy. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:11244–11252. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu C, Wang Z, Lu G, et al. Doxorubicin loaded superparamagnetic PLGA-iron oxide multifunctional microbubbles for dual-mode US/MR imaging and therapy of metastasis in lymph nodes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(9):2307–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mi Y, Zhao J, Feng SS. Targeted co-delivery of docetaxel, cisplatin and herceptin by vitamin E TPGS-cisplatin prodrug nanoparticles for multimodality treatment of cancer. J Control Release. 2013;169(3):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang H, Shen S, Guo J, Chang B, Jiang X, Yang W. Gold nanorods@ mSiO2 with a smart polymer shell responsive to heat/near-infrared light for chemo-photothermal therapy. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:16095–16103. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi M, Liu Y, Xu M, Yang H, Wu C, Miyoshi H. Core/shell Fe3O4 @ SiO2 nanoparticles modified with PAH as a vector for EGFP plasmid DNA delivery into HeLa cells. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11(11):1563–1569. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang XF, Mansouri S, Clime L, Ly HQ, Yahia LH, Veres T. Fe3O4-silica core–shell nanoporous particles for high-capacity pH-triggered drug delivery. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:14450–14457. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Clime L, Roberge H, et al. ph-Triggered doxorubicin delivery based on hollow nanoporous silica nanoparticles with free-standing superparamagnetic Fe3O4 cores. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2011;115(5):1436–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Zheng L, Cai H, et al. Polyethyleneimine-mediated synthesis of folic acid-targeted iron oxide nanoparticles for in vivo tumor MR imaging. Biomaterials. 2013;34(33):8382–8392. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng W, Nie W, He C, et al. Effect of pH-responsive alginate/chitosan multilayers coating on delivery efficiency, cellular uptake and biodistribution of mesoporous silica nanoparticles based nanocarriers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(11):8447–8460. doi: 10.1021/am501337s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Chen H, Zeng D, et al. Core/shell structured hollow mesoporous nanocapsules: a potential platform for simultaneous cell imaging and anticancer drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2010;4(10):6001–6013. doi: 10.1021/nn1015117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinho SL, Pereira GA, Voisin P, et al. Fine tuning of the relaxometry of γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 nanoparticles by tweaking the silica coating thickness. ACS Nano. 2010;4(9):5339–5349. doi: 10.1021/nn101129r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Tang J, Zhao H, Wan J, Chen K. Synthesis of magnetite-silica core-shell nanoparticles via direct silicon oxidation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;432:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen H, Guo J, Chang B, Yang W. pH-responsive composite microspheres based on magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticle for drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;84(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng Q, Yu MZ, Wang JC, et al. Synergistic inhibition of breast cancer by co-delivery of VEGF siRNA and paclitaxel via vapreotide-modified core-shell nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2014;35(18):5028–5038. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu QL, Zhou Y, Guan M, et al. Low-density lipoprotein-coupled N-succinyl chitosan nanoparticles co-delivering siRNA and doxorubicin for hepatocyte-targeted therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35(22):5965–5976. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang S, Yin Q, Zhang Z, et al. Co-delivery of doxorubicin and RNA using pH-sensitive poly (β-amino ester) nanoparticles for reversal of multidrug resistance of breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2014;35(23):6047–6059. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang HY, Kuo WT, Chou MJ, Huang YY. Co-delivery of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor siRNA and doxorubicin by multifunctional polymeric micelle for tumor growth suppression. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;97(3):330–338. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee KY, Seow E, Zhang Y, Lim YC. Targeting CCL21-folic acid-upconversion nanoparticles conjugates to folate receptor-α expressing tumor cells in an endothelial-tumor cell bilayer model. Biomaterials. 2013;34(20):4860–4871. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng H, Zhu JL, Zeng X, Jing Y, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. Targeted gene delivery mediated by folate-polyethylenimine-block-poly(ethylene glycol) with receptor selectivity. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20(3):481–487. doi: 10.1021/bc8004057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Jiang H, Yu Z, et al. Multifunctional uniform core-shell Fe3O4@ mSiO2 mesoporous nanoparticles for bimodal imaging and photothermal therapy. Chem Asian J. 2013;8(2):385–391. doi: 10.1002/asia.201201033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen J, Kim HC, Su H, et al. Cyclodextrin and polyethylenimine functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for delivery of siRNA cancer therapeutics. Theranostics. 2014;4(5):487–497. doi: 10.7150/thno.8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]