Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: drug-eluting stent, everolimus, percutaneous coronary interventions, zotarolimus

Abstract

Background—

Newer-generation drug-eluting stents that release zotarolimus or everolimus have been shown to be superior to the first-generation drug-eluting stents. However, data comparing long-term safety and efficacy of zotarolimus- (ZES) and everolimus-eluting stents (EES) are limited. RESOLUTE all-comers (Randomized Comparison of a Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent With an Everolimus-Eluting Stent for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial compared these 2 stents and has shown that ZES was noninferior to EES at 12-month for the primary end point of target lesion failure. We report the secondary clinical outcomes at the final 5-year follow-up of this trial.

Methods and Results—

RESOLUTE all-comer clinical study is a prospective, multicentre, randomized, 2-arm, open-label, noninferiority trial with minimal exclusion criteria. Patients (n=2292) were randomly assigned to treatment with either ZES (n=1140) or EES (n=1152). Patient-oriented composite end point (combination of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and any revascularizations), device-oriented composite end point (combination of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization), and major adverse cardiac events (combination of all-cause death, all myocardial infarction, emergent coronary bypass surgery, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization) were analyzed at 5-year follow-up. The 2 groups were well-matched at baseline. Five-year follow-up data were available for 98% patients. There were no differences in patient-oriented composite end point (ZES 35.3% versus EES 32.0%, P=0.11), device-oriented composite end point (ZES 17.0% versus EES 16.2%, P=0.61), major adverse cardiac events (ZES 21.9% versus EES 21.6%, P=0.88), and definite/probable stent thrombosis (ZES 2.8% versus EES 1.8%, P=0.12).

Conclusions—

At 5-year follow-up, ZES and EES had similar efficacy and safety in a population of patients who had minimal exclusion criteria.

Clinical Trial Registration—

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00617084.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Newer-generation drug-eluting stents are superior to first-generation drug-eluting stents.

Data comparing long-term safety and efficacy of the second-generation zotarolimus- and everolimuseluting stents are limited.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

RESOLUTE all-comer prospective, multicentre, randomized, 2-arm, open-label, noninferiority trial randomized 2292 patients to treatment with either zotarolimus- or everolimus-eluting stents and followed them for 5 years.

At 5 years, there were no differences in patient-oriented composite end point, device-oriented composite end point, major adverse cardiovascular events, and definite/probable stent thrombosis between zotarolimus- or everolimus-eluting stents–treated patients.

Percutaneous coronary intervention has revolutionized the treatment of patients with flow limiting coronary artery disease. Balloon angioplasty without stenting had limited success because of a high incidence of acute vessel closure caused by dissection or elastic recoil, late vascular remodeling, and neointimal proliferation.1–3 The introduction of bare metal stents improved procedural success and acute outcomes1; however, the clinical outcomes remained affected by high risk of in-stent restenosis.4–6 The drug-eluting stents (DES) substantially reduced neointimal proliferation,5–7 but first-generation DES eluting sirolimus or paclitaxel from a durable polymer raised safety concerns about late and very late stent thrombosis possibly because of delayed endothelialization by the antiproliferative drugs and chronic inflammation or delayed hypersensitivity reaction caused by the polymers in these DES.8–11 The second-generation DES have newer antiproliferative drugs (including zotarolimus and everolimus) and biocompatible or biodegradable polymers along with improved stent design and thinner struts.12 These newer stents have shown promising results and improved clinical outcomes compared with first-generation DES13,14; however, the long-term data on direct comparison between the newer-generation DES is scarce.

The RESOLUTE all-comers (Randomized Comparison of a Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent With an Everolimus-Eluting Stent for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial aimed to compare the Resolute zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES; Medtronic CardioVascular Ltd) and Xience-V everolimus-eluting stent (EES; Abbott Vascular Ltd).13 It has been shown that ZES was noninferior to the EES with respect to the primary end point of target lesion failure at 12 months, which occurred in 8.2% and 8.3% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for noninferiority). There were no significant between-group differences in the rate of death from cardiac causes, any myocardial infarction, repeat revascularization, or stent thrombosis at 12 months.We report the clinical outcomes at the final 5-year follow-up of this trial.

Methods

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committees and informed consent was obtained from all participants (or their guardians).

Study Design and Population

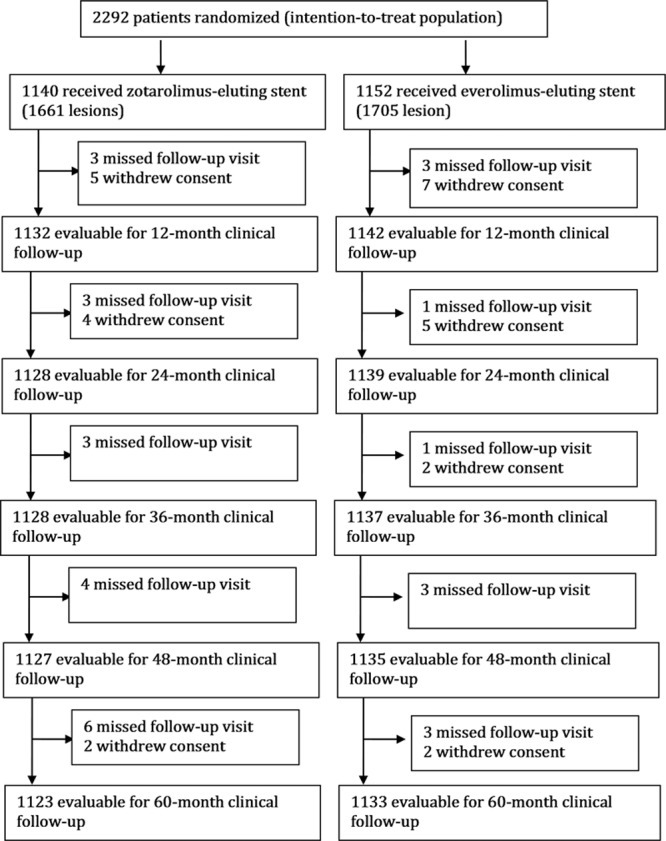

The study design of the RESOLUTE all-comers trial has previously been described13 and is outlined in Figure 1. Briefly, the RESOLUTE all-comers trial is a multicentre prospective double-arm randomized controlled noninferiority trial. From April 30, 2008, to October 28, 2008, we recruited 2292 adult patients with chronic, stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes, including myocardial infarction with or without ST-segment–elevation. The trial was powered for noninferiority testing of the primary end point at 12 months on an intention-to-treat basis; the details of power calculation have been described previously.13 Patients were randomly assigned to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention with either ZES or EES. Patients were eligible if they had at least one coronary lesion with percentage diameter stenosis >50% in a vessel with a reference diameter of 2.25 to 4.0 mm. There were minimal exclusion criteria and no restrictions on total number of treated lesions, treated vessels, lesion length, or number of stents implanted.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of RESOLUTE all-comers trial. RESOLUTE indicates Randomized Comparison of a Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent With an Everolimus-Eluting Stent for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

Study Procedure

Procedures were performed according to standard techniques with the aim to treat all coronary lesions in one session; however, staged procedures within 6 weeks were permitted. Mixture of different DES types was prohibited unless the operator was unable to insert the study stent. Procedural anticoagulation was achieved with unfractionated heparin at a dose of 5000 IU or 70 to 100 IU per kilogram of body weight to maintain an activated clotting time of >250 seconds; the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was at the operators’ discretion. All patients received at least 75 mg of acetylsalicylic acid before the procedure. A loading dose of 300 to 600 mg of clopidogrel was administered if the patient had received no clopidogrel during the previous 7 days. All patients were discharged with a prescription of at least 75 mg of acetylsalicylic acid indefinitely and 75 mg of clopidogrel for a minimum of 6 months after the index procedure.

Follow-Up and Clinical End Points

Patients were followed-up by telephone call or hospital visit at 1, 6, and 12 months and yearly thereafter until 5 years. The primary end point of the trial was target lesion failure (TLF) defined as the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel), and target lesion revascularization (clinically indicated) at 12 months.13 The current article reports the secondary clinical outcomes of this trial at final 5-year follow-up. These predefined end points include device-oriented composite end point or TLF (combination of cardiac death, myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization), patient-oriented composite end point (combination of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and any revascularizations), target vessel failure (combination of cardiac death, myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target vessel revascularization) and major adverse cardiac events (combination of all-cause death, all myocardial infarction, emergent coronary bypass surgery, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization). We have also presented all the individual end points, as defined previously,13 and stent thrombosis as defined by the Academic Research Consortium.15

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and compared using Chi-square or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables are presented as means±standard deviation and compared using the Student’s unpaired t test or 1-way analysis of variance, as appropriate. Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared using log-rank test. A 2-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary).

Results

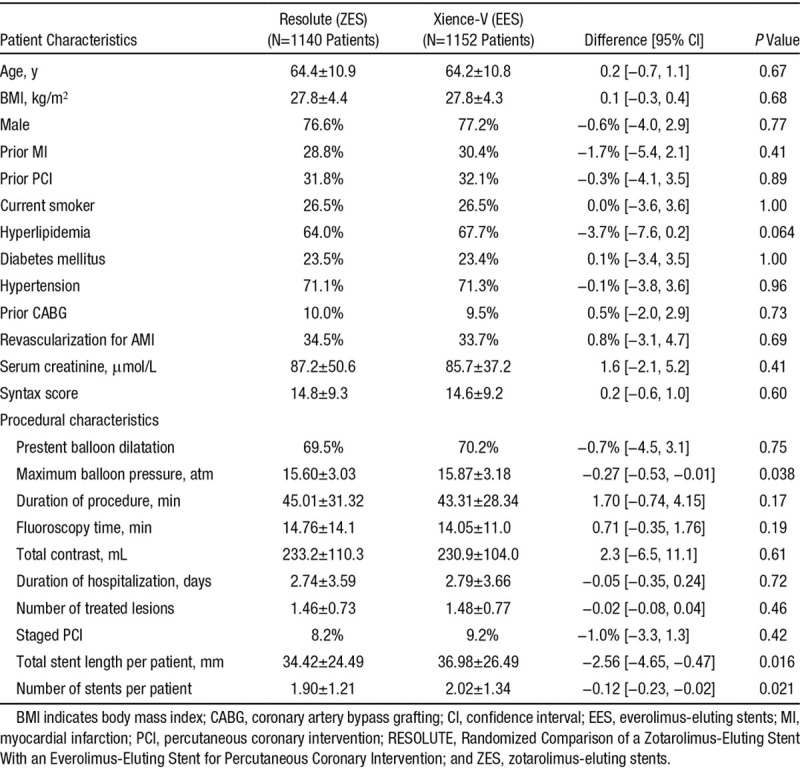

A total of 2292 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to treatment with ZES (n=1140) or EES (n=1152). The 2 groups were well-matched for the baseline demographical, clinical, and angiographic characteristics, except for difference in number of stents used, total length of stents used, and the maximum balloon pressure (Table 1), as previously reported.13 The mean age was 64±11 years, with 77% males and 23% diabetics in both groups. There were ≈34% patients in both study arms who underwent revascularization for acute myocardial infarction. The mean SYNTAX score was also similar in both groups (ZES 14.8±9.3 versus EES 14.6±9.2, P=0.63).

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between the Groups Treated With Zotarolimus- and Everolimus-Eluting Stents

Follow-up data at 5 years were available for 98% patients. There was no difference in usage of dual antiplatelet therapy between the 2 groups at 30 day (ZES 93.9% versus EES 94.3%, P=0.72), 1 year (ZES 84.2% versus 83.3%, P=0.61), 2 year (ZES 17.8% versus 18.2%, P=0.82), and 5 year (ZES 11.0% versus EES 10.9%, P=0.94).

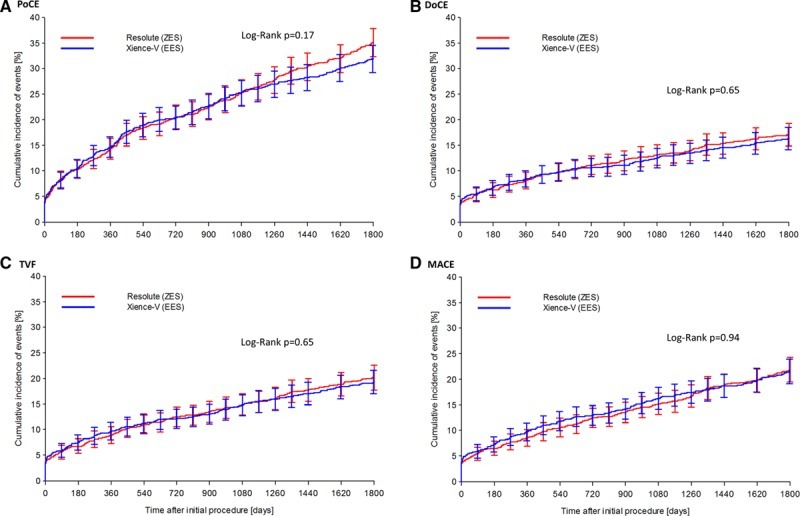

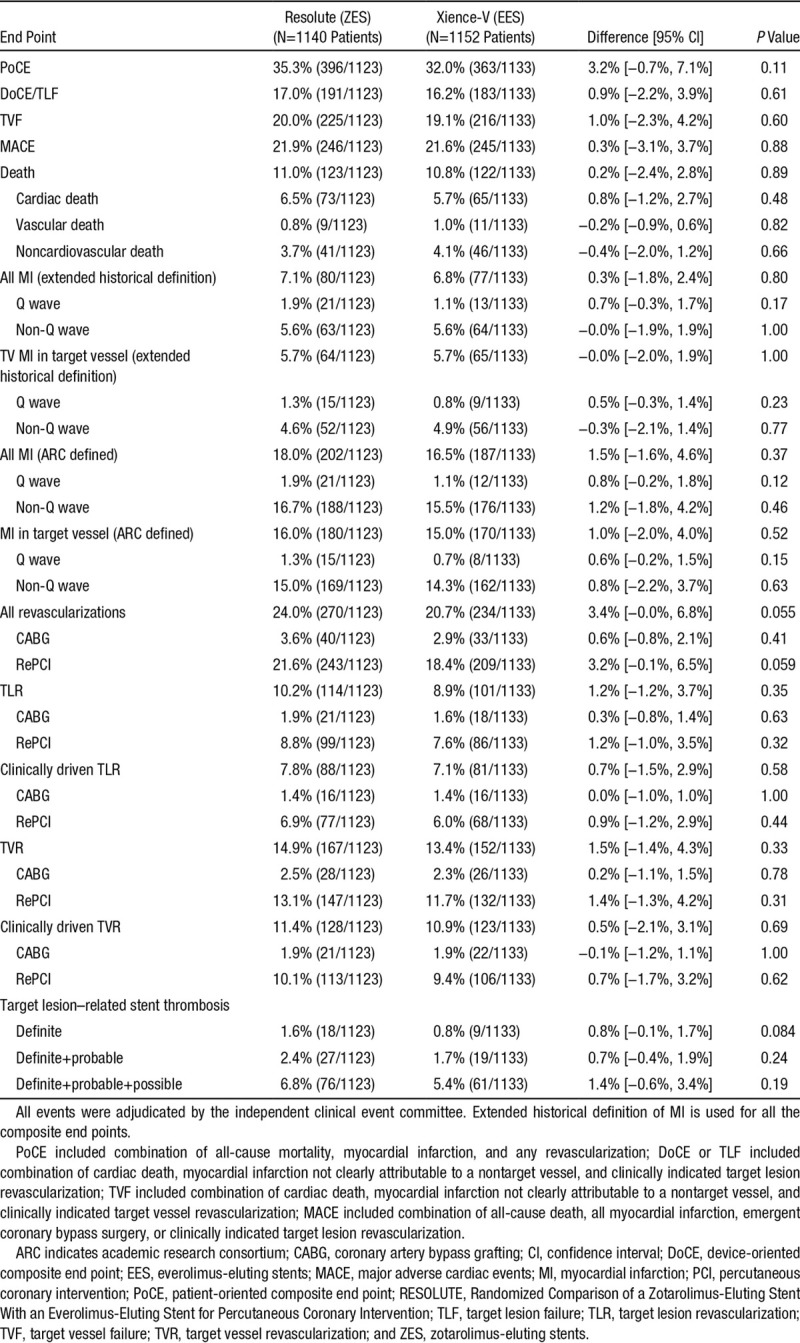

At 5-year follow-up, there were no differences in the incidence of patient-oriented (ZES 35.3% versus EES 32.0%, P=0.11) or device-oriented (ZES 17.0% versus EES 16.2%, P=0.61) end points between the 2 groups (Figure 2). Furthermore, we noted no differences between the 2 stent groups for major adverse cardiac events (ZES 21.9% versus EES 21.6%, P=0.88) and target vessel failure (ZES 20.0% versus EES 19.1%, P=0.60) at the final follow-up (Figure 2). The 2 groups also had no difference in other clinical end points, including death, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, revascularization, and stent thrombosis (Table 2). The detailed incidence of stent thrombosis in the 2 groups during 5-year follow-up period is provided in Table in the Data Supplement.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents for clinical end points. Zotarolimus- and everlomius-eluting stents had similar patient-oriented composite end point (PoCE; combination of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and any revascularization; A), device-oriented composite end point (DoCE; combination of cardiac death, myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization; B), target vessel failure (TVF; combination of cardiac death, myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target vessel revascularization; C), and major adverse cardiac events (MACE; combination of all-cause death, all myocardial infarction, emergent coronary bypass surgery, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization; D). Error bars indicate a point-wise 2-sided 95% confidence interval (1.96 SD). Standard error based on the Greenwood Formula.

Table 2.

All Clinical End Points at 5-Year Follow-Up

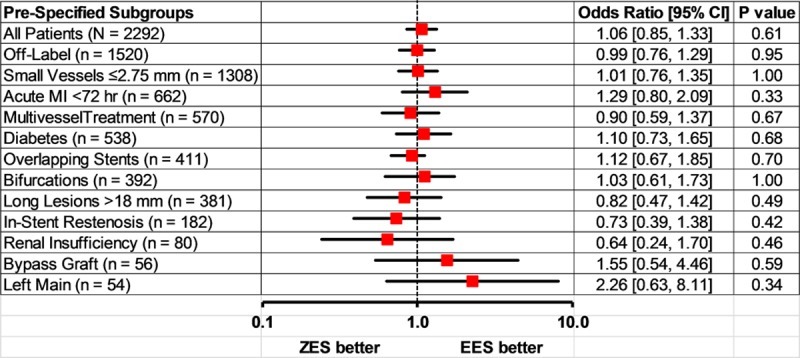

Stratified analysis of the primary end point (device-oriented composite end point/TLF) at 5 years across different patient subgroups (including diabetics and acute coronary syndromes) and anatomic complexity of coronary artery disease revealed no difference in outcomes between ZES- and EES-treated patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing prespecified subgroups analysis comparing zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents for target lesion failure at 5-year follow-up. Zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents had similar device-oriented composite end point (DoCE) or target lesion failure (TLF), including combination of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI) not clearly attributable to a nontarget vessel, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularization. Error bars indicate a point-wise 2-sided 95% confidence interval (1.96 SD). Standard error based on the Greenwood Formula. EES indicates everolimus-eluting stents; and ZES, zotarolimus-eluting stents.

Discussion

The RESOLUTE all-comers trial directly compared the performance of 2 newer-generation stents in an all-comers population over a long follow-up period. The main finding of the present study is that at 5-year follow-up, ZES and EES were similar in clinical efficacy and safety with no difference in either patient-oriented and device-oriented end points or stent thrombosis.

The DES are the main stay in treating patients with flow-limiting coronary lesions.16,17 First-generation DES showed a substantial improvement reduction in restenosis and need for repeat revascularization compared with bare metal stents.6,7 However, these first-generation devices failed in adding a major gain in terms of long-term mortality18 and a major concern remained on long-term safety, in particular, related to late stent thrombosis.8,9,19–24 The second-generation DES, with novel stent design/material, improved polymer biocompatibility, and novel antiproliferative drugs were developed to improve acute performance and long-term outcomes.11,14

ZES and EES have previously been shown to be equivalent in terms of procedural success, angiographic late lumen loss, and short-/midterm clinical outcomes.13,25,26 Our data confirms that they remain comparable over a long follow-up period of 5 years. These results are consistent with reports from other trials and registries.27,28 The Real-World Endeavor Resolute Versus Xience V Drug-Eluting Stent Study in Twente (TWENTE) trial randomly assigned patients to ZES (n=697) or EES (n=694) and found no difference in patient-oriented composite end point (ZES 16.4% versus EES 17.1%, P=0.75) and target vessel failure (ZES 10.8% versus EES 11.6, P=0.65) at 2-year follow-up.27 It has also been shown that there is no difference in outcomes between the 2 stents when used for patients with complex coronary disease,29,30 long lesions requiring overlapping stents,31 unprotected left main stem,32 small diameter (<2.7 mm) vessels,33 and bifurcation lesions.34 Our findings from stratified analyses corroborate these studies.

The incidence of stent thrombosis in ZES- or EES-treated patients in this study was similar and comparable to other studies. In the LEADERS trial, the incidence of definite/probable stent thrombosis at 5 year for second-generation biolimus eluting stent was 3.6%. In the TWENTE trial, 95% patients were asked to discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy after 12 months. Two-year rates of definite or probable stent thrombosis were similar (ZES 1.2% versus EES 1.4%, P=0.63).27

ZES (cobalt-chromium platform) has been reported to be equivalent to the newer platinum-chromium (Pt-Cr)– based EES (Promus Element, Boston Scientific Ltd),35,36 whereas Pt-Cr–based (Promus Element) and cobalt-chromium–based (Xience-V) EES are also comparable in outcomes.37 HOST-ASSURE trial randomized 3755 all-comer patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention to PtCr-EES or ZES. At 1-year, the primary end point of TLF occurred in 2.9% and 2.9% of the population in the PtCr-EES and ZES groups, respectively (superiority P=0.98, noninferiority P=0.025). There were no significant differences in the individual components of TLF, as well as the patient-oriented clinical outcome.35 Another recently reported all-comer trial (n=1811 patients) comparing cobalt-chromium–based ZES (n=906) against Promus Element (Pt-Cr EES, n=905) has shown no difference in the primary end point of target vessel failure or its individual components at 12-month follow-up. There was also no difference in stent thrombosis (ZES 0.3% versus Promus Element 0.7%, P=0.34).36 There was also no difference in the outcomes for patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction.36

Limitations

This study’s powered primary end point was target lesion failure at 1 year, and the clinical outcome at the final 5-year follow-up is a secondary end point. However, it was a prespecified secondary end point, with all events adjudicated by an independent Clinical Events Committee.

Conclusions

ZES and EES offered similar patient- and device-related end points at 5-year follow-up. Both ZES and EES are the most widely used DES at the moment, and our results indeed confirm that these stents have equally good outcomes during a long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all study centres and participants in this trial, whose work made this study possible.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA. The funder had no influence on analysing and interpretation of data.

Disclosures

Dr Silber has received research grants to the institution from Biotronik and St Jude. Dr Richardt has received consultancy fee from Abbott Vascular. Dr Negoita is a full time employee of Medtronic. The other authors report no conflicts.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The Data Supplement is available at http://circinterventions.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002230/-/DC1.

References

- 1.de Feyter PJ, de Jaegere PP, Serruys PW. Incidence, predictors, and management of acute coronary occlusion after coronary angioplasty. Am Heart J. 1994;127:643–651. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, Macaya C, Rutsch W, Heyndrickx G, Emanuelsson H, Marco J, Legrand V, Materne P. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:489–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, Schatz RA, Savage MP, Penn I, Detre K, Veltri L, Ricci D, Nobuyoshi M. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:496–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310802. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serruys PW, Strauss BH, Beatt KJ, Bertrand ME, Puel J, Rickards AF, Meier B, Goy JJ, Vogt P, Kappenberger L. Angiographic follow-up after placement of a self-expanding coronary-artery stent. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:13–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240103. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, Perin M, Colombo A, Schuler G, Barragan P, Guagliumi G, Molnàr F, Falotico R RAVEL Study Group. Randomized Study with the Sirolimus-Coated Bx Velocity Balloon-Expandable Stent in the Treatment of Patients with de Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–1780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, Hermiller J, O’Shaughnessy C, Mann JT, Turco M, Caputo R, Bergin P, Greenberg J, Popma JJ, Russell ME TAXUS-IV Investigators. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:221–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O’Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E, Cheneau E, Ong AT, Kinnaird T, Suddath WO, Weissman NJ, Torguson R, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Waksman R, Serruys PW. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 2004;364:1519–1521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17275-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagerqvist B, Carlsson J, Fröbert O, Lindbäck J, Scherstén F, Stenestrand U, James SK Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry Study Group. Stent thrombosis in Sweden: a report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:401–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.844985. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.844985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E, Kutys R, Skorija K, Gold HK, Virmani R. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joner M, Nakazawa G, Finn AV, Quee SC, Coleman L, Acampado E, Wilson PS, Skorija K, Cheng Q, Xu X, Gold HK, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Endothelial cell recovery between comparator polymer-based drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.030. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iqbal J, Gunn J, Serruys PW. Coronary stents: historical development, current status and future directions. Br Med Bull. 2013;106:193–211. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldt009. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldt009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serruys PW, Silber S, Garg S, van Geuns RJ, Richardt G, Buszman PE, Kelbaek H, van Boven AJ, Hofma SH, Linke A, Klauss V, Wijns W, Macaya C, Garot P, DiMario C, Manoharan G, Kornowski R, Ischinger T, Bartorelli A, Ronden J, Bressers M, Gobbens P, Negoita M, van Leeuwen F, Windecker S. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:136–146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, Mastali K, Wang JC, Caputo R, Doostzadeh J, Cao S, Simonton CA, Sudhir K, Lansky AJ, Cutlip DE, Kereiakes DJ SPIRIT IV Investigators. Everolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1663–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Falk V, Folliguet T, Garg S, Huber K, James S, Knuuti J, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Menicanti L, Ostojic M, Piepoli MF, Pirlet C, Pomar JL, Reifart N, Ribichini FL, Schalij MJ, Sergeant P, Serruys PW, Silber S, Sousa Uva M, Taggart D. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–2555. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iqbal J, Serruys PW, Taggart DP. Optimal revascularization for complex coronary artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:635–647. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.138. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, Kaiser C, Valgimigli M, Kelbaek H, Menichelli M, Sabaté M, Suttorp MJ, Baumgart D, Seyfarth M, Pfisterer ME, Schömig A. Analysis of 14 trials comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1030–1039. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Grieco N, Motta T, Mihalcsik L, Tespili M, Valsecchi O, Kolodgie FD. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004;109:701–705. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camenzind E, Steg PG, Wijns W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents: a cause for concern. Circulation. 2007;115:1440–1455, discussion 1455. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666800. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, Abrecht L, Vaina S, Morger C, Kukreja N, Jüni P, Sianos G, Hellige G, van Domburg RT, Hess OM, Boersma E, Meier B, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60314-6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG, Schofer J, Dawkins KD, Morice MC, Colombo A, Schampaert E, Grube E, Kirtane AJ, Cutlip DE, Fahy M, Pocock SJ, Mehran R, Leon MB. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordmann AJ, Briel M, Bucher HC. Mortality in randomized controlled trials comparing drug-eluting vs. bare metal stents in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2784–2814. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl282. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT, Rickenbacher P, Hunziker P, Mueller C, Jeger R, Bader F, Osswald S, Kaiser C BASKET-LATE Investigators. Late clinical events after clopidogrel discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents: an observational study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2584–2591. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JM, Youn TJ, Park JJ, Oh IY, Yoon CH, Suh JW, Cho YS, Cho GY, Chae IH, Choi DJ. Comparison of 9-month angiographic outcomes of Resolute zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting stents in a real world setting of coronary intervention in Korea. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Birgelen C, Basalus MW, Tandjung K, van Houwelingen KG, Stoel MG, Louwerenburg JH, Linssen GC, Saïd SA, Kleijne MA, Sen H, Löwik MM, van der Palen J, Verhorst PM, de Man FH. A randomized controlled trial in second-generation zotarolimus-eluting Resolute stents versus everolimus-eluting Xience V stents in real-world patients: the TWENTE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1350–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.008. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tandjung K, Sen H, Lam MK, Basalus MW, Louwerenburg JH, Stoel MG, van Houwelingen KG, de Man FH, Linssen GC, Saïd SA, Nienhuis MB, Löwik MM, Verhorst PM, van der Palen J, von Birgelen C. Clinical outcome following stringent discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy after 12 months in real-world patients treated with second-generation zotarolimus-eluting resolute and everolimus-eluting Xience V stents: 2-year follow-up of the randomized TWENTE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2406–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park KW, Lee JM, Kang SH, Ahn HS, Yang HM, Lee HY, Kang HJ, Koo BK, Cho J, Gwon HC, Lee SY, Chae IH, Youn TJ, Chae JK, Han KR, Yu CW, Kim HS. Safety and efficacy of second-generation everolimus-eluting Xience V stents versus zotarolimus-eluting resolute stents in real-world practice: patient-related and stent-related outcomes from the multicenter prospective EXCELLENT and RESOLUTE-Korea registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.015. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sen H, Lam MK, Tandjung K, Löwik MM, Stoel MG, de Man FH, Louwerenburg JH, van Houwelingen GK, Linssen GC, Doggen CJ, Basalus MW, von Birgelen C. Complex patients treated with zotarolimus-eluting resolute and everolimus-eluting Xience V stents in the randomized TWENTE trial: comparison of 2-year clinical outcome. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:74–81. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25464. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefanini GG, Serruys PW, Silber S, Khattab AA, van Geuns RJ, Richardt G, Buszman PE, Kelbæk H, van Boven AJ, Hofma SH, Linke A, Klauss V, Wijns W, Macaya C, Garot P, Di Mario C, Manoharan G, Kornowski R, Ischinger T, Bartorelli AL, Gobbens P, Windecker S. The impact of patient and lesion complexity on clinical and angiographic outcomes after revascularization with zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents: a substudy of the RESOLUTE All Comers Trial (a randomized comparison of a zotarolimus-eluting stent with an everolimus-eluting stent for percutaneous coronary intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2221–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.036. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li XT, Sun H, Zhang DP, Xu L, Ni ZH, Xia K, Liu Y, Chi YH, He JF, Li WM, Wang HS, Wang LF, Yang XC. Two-year clinical outcomes of patients with overlapping second-generation drug-eluting stents for treatment of long coronary artery lesions: comparison of everolimus-eluting stents with resolute zotarolimus-eluting stents. Coron Artery Dis. 2014;25:405–411. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000098. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehilli J, Richardt G, Valgimigli M, Schulz S, Singh A, Abdel-Wahab M, Tiroch K, Pache J, Hausleiter J, Byrne RA, Ott I, Ibrahim T, Fusaro M, Seyfarth M, Laugwitz KL, Massberg S, Kastrati A ISAR-LEFT-MAIN 2 Study Investigators. Zotarolimus- versus everolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2075–2082. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.044. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho SC, Jeong MH, Kim W, Ahn Y, Hong YJ, Kim YJ, Kim CJ, Cho MC, Han KR, Kim HS Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Investigators. Clinical outcomes of everolimus- and zotarolimus-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction for small coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2014;63:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.10.016. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrarello S, Costopoulos C, Latib A, Naganuma T, Sticchi A, Figini F, Basavarajaiah S, Carlino M, Chieffo A, Montorfano M, Kawaguchi M, Naim C, Giannini F, Colombo A. The role of everolimus-eluting and resolute zotarolimus-eluting stents in the treatment of coronary bifurcations. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:436–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park KW, Kang SH, Kang HJ, Koo BK, Park BE, Cha KS, Rhew JY, Jeon HK, Shin ES, Oh JH, Jeong MH, Kim S, Hwang KK, Yoon JH, Lee SY, Park TH, Moon KW, Kwon HM, Hur SH, Ryu JK, Lee BR, Park YW, Chae IH, Kim HS HOST–ASSURE Investigators. A randomized comparison of platinum chromium-based everolimus-eluting stents versus cobalt chromium-based Zotarolimus-Eluting stents in all-comers receiving percutaneous coronary intervention: HOST-ASSURE (harmonizing optimal strategy for treatment of coronary artery stenosis-safety & effectiveness of drug-eluting stents & anti-platelet regimen), a randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt A):2805–2816. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Birgelen C, Sen H, Lam MK, Danse PW, Jessurun GA, Hautvast RW, van Houwelingen GK, Schramm AR, Gin RM, Louwerenburg JW, de Man FH, Stoel MG, Löwik MM, Linssen GC, Saïd SA, Nienhuis MB, Verhorst PM, Basalus MW, Doggen CJ, Tandjung K. Third-generation zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting stents in all-comer patients requiring a percutaneous coronary intervention (DUTCH PEERS): a randomised, single-blind, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383:413–423. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62037-1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone GW, Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, Farah B, Dubois CL, Feldman RL, Dens J, Hagiwara N, Allocco DJ, Dawkins KD PLATINUM Trial Investigators. A prospective, randomized evaluation of a novel everolimus-eluting coronary stent: the PLATINUM (a Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Trial to Assess an Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System [PROMUS Element] for the Treatment of Up to Two de Novo Coronary Artery Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.016. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]