Abstract

Although marital separation is an inherently social experience, most research on adults’ psychological adjustment following a romantic separation focuses on intrapersonal characteristics, or individual differences (e.g., attachment style, personality, longing) that condition risk for poor psychological outcomes. We know little about how these individual differences interact with interpersonal processes, such as contact between ex-partners. In the current study, we sought to understand how adults’ continued attachment to (and longing for) an ex-partner, and both nonsexual and sexual contact with an ex-partner (CWE and SWE, respectively), are related to adults’ post-separation psychological adjustment among 137 (n = 50 men) adults reporting recent marital separations. Data revealed that (1) less separation acceptance was associated with poorer psychological adjustment; (2) among people having CWE, those reporting less acceptance reported significantly poorer adjustment relative to those reporting more acceptance; (3) among people reporting more acceptance, those having CWE reported significantly better adjustment relative to those not having CWE; (4) among people not having SWE, those reporting less acceptance reported significantly poorer adjustment relative to those reporting more acceptance; and (5) among people reporting less acceptance, those having SWE reported significantly better adjustment relative to those not having SWE. We discuss the findings in terms of adult attachment, pair-bonding, and the loss of coregulatory processes following marital separation.

How can you get over someone if you're constantly in touch with him? You're indulging and/or torturing yourself, and it's unhealthy.

—Glamour Magazine (Meanley, 2010)

Although the topic of contact with a former romantic partner is frequently discussed in the popular media, few statements about the psychological effects of maintaining a relationship with an ex-partner are grounded in science. People who fail to excise ex-partners from their lives are typically portrayed as weak, masochistic, or poorly adjusted to their separations—but are there circumstances that dictate whether it is, in fact, unhealthy to maintain contact with a former lover or spouse?

Approximately 50% of divorced people report continued contact with their former spouses two and ten years after separating (Fischer, de Graaf, & Kalmijn, 2005; Masheter, 1991), and more than half of people report being friends with their ex-partners after a non-marital romantic breakup (e.g., Schneider & Kenny, 2000). The few data that exist on the topic of interpersonal contact following a romantic separation do not paint a coherent picture. Some researchers have found contact with an ex-partner to be associated with greater emotional distress following a romantic separation (e.g., Sbarra & Emery, 2005), whereas other researchers have found that this is not always the case (e.g., Masheter, 1991). We believe this inconsistency underscores the need to explore potential moderating variables in order to better understand precisely when contact with an ex-partner is associated with better or worse psychological adjustment following a romantic separation.

In this report, we examine whether nonsexual and sexual contact with an ex-partner (CWE and SWE, respectively) and the degree to which one longs for (remains psychologically attached to) an ex-partner interact to predict psychological adjustment following a marital separation. Because sexual behavior constitutes a core element of the adult attachment system (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007), the study of SWE—as distinct from non-sexual CWE—may be useful in understanding how people cope with relationship dissolutions, and, in the case of this study, marital separation in particular.

ATTACHMENT THEORY AND ROMANTIC SEPARATIONS

Attachment theory provides a useful vantage point for exploring how different forms of contact with an ex-partner may be associated with adjustment to romantic separations. The attachment system is characterized as an evolutionary adaptation that functions to protect against danger by causing people to seek out proximity to an attachment figure, especially in situations that threaten well-being (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Characteristic patterns of responding to relationship threats are well established in infants and young children (Bowlby, 1982). In adulthood, romantic relationships share many features of infant-caregiver attachment bonds (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2004; Shaver, Hazan, & Bradshaw, 1988), and as in childhood, threats to felt security in adulthood elicit patterns of appraisal, coping, and emotion that differ depending on one's attachment style (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). In many circumstances, romantic separations represent such a threat and can induce feelings of emotional or physical abandonment, anxiety about the future, or lingering love for the lost romantic partner. Sbarra and Hazan (2008) proposed that attachment relationships are defined by the coregulation of felt security within a relationship, and that the loss of felt security associated with romantic separations can result in psychological and physiological dysregulation. In order to cope well with separation distress, people must find a way to soothe themselves (i.e., self-regulate) following the separation experience (Sbarra & Hazan, 2008), and this often involves a reallocation of attentional resources away from an ex-partner and toward other supportive people in one's social network (e.g., Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, 2003; Spielmann, MacDonald, & Wilson, 2009).

From this perspective, romantic separations present an unusual challenge: The primary source of distress in a romantic separation— the ex-partner— is the very person to whom we most often want to turn in times of distress. For people who remain highly attached to an ex-partner, having contact with that ex-partner may bring temporary relief by providing a degree of felt security, but it may also invite a firestorm of pain or rumination about what was lost in the separation, which, in turn, can prolong distress. It is unclear under what circumstances people experience these different outcomes. Assessing the extent to which separated individuals remain attached to their ex-partners may provide critical insight into this dynamic. Furthermore, assessing continued emotional attachment to an ex-partner in combination with interpersonal contact with an ex-partner may shed light on the specific situations in which longing and acceptance (relationship- and person-specific constructs) predict more global affective disturbances (e.g., intrusive emotional distress, negative emotional experience) in the aftermath of a separation experience.

SEX AND THE ATTACHMENT SYSTEM

Although attachment and caregiving occur across a variety of close relationships, sexual contact distinguishes romantic attachment relationships from other adult relationships (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Hazan & Zeifman, 1994) and represents an important avenue through which romantic pair-bonds are deepened and maintained (Sbarra & Hazan, 2008). The pair-bonding system comprises three behavioral subsystems: attachment, sexual mating, and caregiving (Shaver, Hazan, & Bradshaw, 1988). Sexual contact is associated with the activation of physiological reward systems (Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005); people report high levels of well-being during sexual activity (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010) and frequency of sexual activity is positively associated with well-being for both married and unmarried dating people (Call, Sprecher, & Schwartz, 1995; McGuire & Barber, 2010).

These positive associations, however, may not hold when relationships end, and sexual contact with an ex-partner (SWE) may derail the process of recovering from the recent loss. In the wake of a romantic separation, continuing to have SWE may serve to maintain psychological attachment to the ex-partner (Davis et al., 2003), and, like CWE, this may or may not be associated with detrimental outcomes. SWE may comfort people who are unable or unwilling to come to terms with the end of their romantic relationships by delaying the onset of separation anxiety and separation-related distress. On the other hand, having SWE may maintain the attachment relationship and/or provoke rumination about one's ex that interferes with moving on. Thus, the degree to which one finds having SWE distressing and the degree to which one remains attached to an ex-partner may operate together to predict psychological adjustment.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The literature on how people cope with and adjust to marital separations has, for the most part, neglected the social context of the separation experience (see Sbarra & Emery, 2008). The end of marriage is a fundamentally social experience—we fight with ex-partners, we discuss how our relationships with them deteriorated, and, if children are involved, we coordinate childcare and celebrate birthdays, holidays, and graduations. The absence of research regarding the interpersonal dynamics of marital separation is conspicuous. In the present study, we addressed this gap in the literature by examining the associations among CWE, SWE, separation acceptance, and psychological adjustment in 137 adults reporting a recent marital separation.

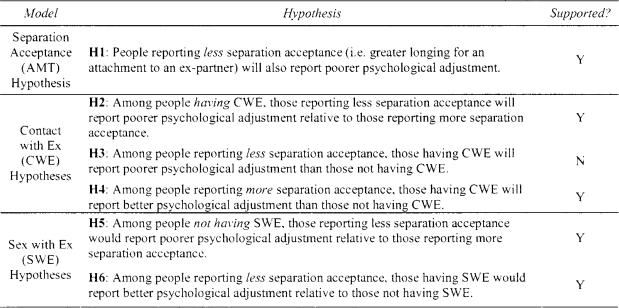

Figure 1 outlines the primary hypotheses of this study. We first predicted that less separation acceptance (i.e., greater longing for and attachment to an ex-partner) would be associated with poorer psychological adjustment (H1). Because our data are cross-sectional, we recognize that there is no way to disentangle the directionality of association between separation acceptance and global psychological adjustment. In considering how two related but conceptually distinct self-report variables function together following marital separation, our guiding theory (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007) suggests that longing/separation acceptance (and attachment to an ex-partner) would be a precursor to more global distress; therefore, we specify the models of interest with longing/separation acceptance as the predictor variable and global psychological adjustment as the outcome of interest, but recognize that our cross-sectional data cannot provide a precise picture of causal directionality.

FIGURE 1.

Hypotheses derived from attachment theory. (See Table 2 for model parameters.)

Second, we predicted that among people having CWE, those reporting less separation acceptance would report poorer psychological adjustment relative to those reporting more separation acceptance (H2). We based this prediction on the idea that CWE may reactivate the attachment system (Sbarra & Hazan, 2008) and leave people with unmet attachment needs, which can be highly distressing for people who long for reunion with an ex-partner. Along the same theoretical lines, we also predicted that among people reporting less separation acceptance, those having CWE would report poorer psychological adjustment than those not having CWE (H3). In contrast, we predicted that among people reporting more separation acceptance (i.e., less longing), those having CWE might benefit from maintaining contact—and potentially a continued friendship—with an ex-partner, and therefore report better adjustment than those not having CWE (H4).

Finally, given the special role of sexual behavior in the context of pair-bonding and the idea that sexual contact can fulfill an important attachment need, we predicted a different set of results when examining the interactive effects of SWE and separation acceptance on psychological adjustment. Among people not having SWE, less separation acceptance may result in a distressing unmet attachment need state. Hence, we predicted that among people not having SWE, those reporting less separation acceptance would report poorer adjustment relative to those reporting more separation acceptance (H5). In keeping with this idea, we predicted that among people reporting less separation acceptance, those having SWE would report better adjustment than those not having SWE (H6). We based this prediction on the idea that people reporting less separation acceptance have continued attachment needs that intimate contact with an ex-partner may fulfill.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were 137 (50 men) community-dwelling adults (mean age = 40.60 years, SD = 9.86 years) recruited through newspaper advertisements, divorce recovery groups, and the local family and conciliation court. Participants reported having experienced marital separations an average of 3.77 months before entering the study (SD = 1.92 months). One hundred and six participants (77.4%) described themselves as White (non-Hispanic), 18 (13.1%) as Hispanic, 3 (2.2%) as African-American, 2 (1.5%) as Asian, 2 (1.5%) as Native American, and 6 (4.5%) as other. On average, participants reported their previous relationship length to be 158.86 months (SD = 99.78 months), and the time since separating from their partners to be 3.77 months (SD = 1.91 months). Fifteen (10.9%) participants described themselves as being entirely responsible for ending the relationship and 42 (30.7%) described themselves as being mostly responsible, whereas 24 (17.5%) participants reported that their partners were entirely responsible and 53 (38.7%) reported that their partners were mostly responsible. Three (2.2%) did not answer. Participants reported spending an average of approximately 12.1 minutes per hour thinking about their ex-partner and the demise of their marriage (SD = 14.3 min; range = 0–60 min) during the two weeks prior to their laboratory visit.

PROCEDURE

Participants were mailed a packet that included demographic questions as well as the self-report items and questionnaires described below. Participants completed the packets and brought them to the laboratory.

MEASURES

Sexual Contact with an Ex-Partner (SWE)

Each participant answered the question, “Since the separation have you and your former partner engaged in sexual relations?” by indicating whether or not he or she had engaged in sexual relations with his or her partner. Of the 137 participants who participated in the study, 30 (21.9%) reported engaging in SWE.

Contact with an Ex-Partner (CWE)

Each participant answered the question, “Currently, do you have any contact with this person?” by indicating whether or not he or she was in contact with his or her ex-partner. Of the 137 participants who participated in the study, 113 (82.5%) reported having CWE.

Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES–R)

The 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1997) served as an index of psychological adjustment. Items were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Higher scores reflect greater emotional intrusion, somatic hyperarousal, and avoidance behaviors following the recent separation (M = 32.75, SD = 16.81). Items include “I have trouble concentrating,” and “I feel irritable and angry.” According to Creamer, Bell, and Failla (2003), the highest overall diagnostic power of this scale was achieved with a cutoff score of 33, and the IES-R may be sensitive to a more general construct of distress among people with lower symptom levels. Thus, in the current sample, those who scored one standard deviation above the mean on the IES-R reported considerable separation-related emotional intrusion, hyperarousal, and avoidance behaviors. The IESR’s internal consistency in the present sample was high (α = .93).

Acceptance of Marital Termination (AMT)

The AMT used here is a modified version of Kitson's (1982) Acceptance of Marital Termination scale, and assesses longing for, and degree of acceptance of the loss of, a specific former romantic partner. We henceforth refer to this construct as separation acceptance. The AMT score is calculated as the sum of 11 items (range = 14–44), and items are assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all my feelings) to 4 (very much my feelings). We reversed the item scores so that lower scores indicate less separation acceptance, or greater longing for one’s former partner (M = 29.62, SD = 8.82). Items include “I find myself thinking a lot about my former spouse,” and “sometimes I just can’t believe that we separated/divorced.” The internal consistency of the AMT scale in the present sample was high (α = .91).

Although the AMT contains some items that are similar to items in the IES-R, and the two measures are correlated (see Table 1), these composites assess fundamentally distinct constructs. The IES-R assesses global adjustment following a life event, and the content of its items is not interpersonally-focused. In contrast, the AMT assesses ongoing attachment to a former partner, an inherently interpersonal construct. We believe that this is an important distinction, and that it may explain why these variables operate differently and were not statistically interchangeable within our models.1

TABLE 1.

correlations Among predictor and outcome Variables

| parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Separate | X | ||||||||

| 2. Biol. Children | .04 | X | |||||||

| 3. Initiator Stat. | −.02 | .00 | X | ||||||

| 4. Rel. Length | .01 | .41** | .05 | X | |||||

| 5. Gender | .00 | −.09 | −.08 | −.06 | X | ||||

| 6. AMT | −.04 | .06 | −.43** | −.11 | .08 | X | |||

| 7. CWE | −.08 | .18* | −.14 | .17 | −.10 | −.12 | X | ||

| 8. SWE | .02 | .10 | .14 | −.03 | .07 | −.23** | .24** | X | |

| 9. IES | .08 | −.06 | .33** | −.04 | −.01 | −.63** | −.05 | .10 | X |

| M | 3.77 | .50 | 2.64 | 158.86 | .64 | 29.61 | .83 | .22 | 32.75 |

| SD | 1.92 | .50 | .90 | 99.78 | .48 | 8.82 | .38 | .42 | 16.81 |

Note. Separate = Time since separation (months); Biol. Children = Biological children with ex-partner (N, Y = −1, 1); Initiator Stat. = Who was responsible for ending relationship; Rel. Length = Length of relationship (months); Gender = Participant gender (M, F = −1, 1); AMT = Separation acceptance (Acceptance of Marital Termination scale); CWE = Self-reported general contact with ex-partner (not having CWE, having CWE = −1, 1); SWE = Self-reported sexual activity with ex-partner (not having SWE, having SWE = −1, 1); IES-R = Psychological adjustment (Impact of Event Scale-Revised). See Method for complete covariate descriptions.

p < .05

p < .01

Relationship-Specific Covariates

We assessed several previously-documented predictors of post-separation adjustment. Participants reported the length of their former relationship (e.g., Simpson, 1987); how long it had been since the relationship had ended (e.g., Sbarra & Emery, 2005); whether the end of their relationship was their choosing or their partner's on a 4-point scale: 1 (you were totally responsible); 2 (both you and your partner were responsible, but more so you); 3 (both you and your partner were responsible, but more so your partner); and 4 (your partner was totally responsible; e.g., Kitson & Holmes, 1992; Sbarra, 2006; Wang & Amato, 2000); and whether they had biological children with their ex-partners (e.g., Sbarra & Emery, 2008). These covariates, in addition to participant gender, were included in all analyses.

RESULTS

Zero-order correlations among all variables are presented in Table 1. Participants’ separation acceptance (AMT) was significantly correlated with psychological adjustment (IES-R) such that less separation acceptance was associated with poorer psychological adjustment (r = -.63). Contact with an ex-partner (CWE) and sexual contact with an ex-partner (SWE) were not significantly correlated with psychological adjustment. SWE (but not CWE) was negatively correlated with separation acceptance (r = -.23).

Figure 1 outlines all study hypotheses, which we examine in order. After accounting for relevant covariates, there was a significant main effect of separation acceptance on psychological adjustment, B = -1.25, β = -.65, t = -8.14, p < .0012,3 (Table 2, Model 1). As predicted (H1), those reporting less separation acceptance reported poorer adjustment than those reporting more separation acceptance. There were no main effects of SWE or CWE on adjustment.

TABLE 2.

Regressions of Non-sexual Ex-partner contact (CWE), sexual Ex-partner contact (SWE), Separation Acceptance (AMT), and their Interactions on Psychological Adjustment (IES-R)

| DV | parameter | B | SE B | β | t | Sig. | r2 (Adj. r2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Constant | 70.58 | 4.95 | 14.26 | .00 | ||

| Separate | .31 | .63 | .03 | .48 | .63 | ||

| Biol. Children | .58 | 1.33 | .03 | .44 | .66 | ||

| Initiator Status | .88 | 1.51 | .05 | .58 | .56 | ||

| Rel. Length | −.02 | .01 | −.10 | −1.34 | .18 | ||

| Gender | .23 | 1.27 | .01 | .18 | .86 | ||

| AMT | −1.25 | .15 | −.65 | −8.14 | .00 | ||

| CWE | −2.19 | 1.78 | −.09 | −1.23 | .22 | ||

| SWE | −1.12 | 1.59 | −.05 | −.70 | .48 | .43 (.39) | |

| Model 2 | Constant | 57.30 | 7.40 | 7.74 | .00 | ||

| Separate | .16 | .62 | .02 | .25 | .80 | ||

| Biol. Children | .29 | 1.31 | .02 | .22 | .83 | ||

| Initiator Status | .50 | 1.49 | .03 | .33 | .74 | ||

| Rel. Length | −.02 | .01 | −.10 | −1.27 | .21 | ||

| Gender | .06 | 1.25 | .00 | .05 | .96 | ||

| AMT | −.84 | .23 | −.44 | −3.65 | .00 | ||

| CWE | −1.32 | 1.79 | −.06 | −.74 | .46 | ||

| SWE | −1.33 | 1.56 | −.06 | −.85 | .40 | ||

| CWE × AMT | −.54 | .23 | −.28 | −2.37 | .02 | .46 (.42) | |

| Model 3 | Constant | 64.23 | 5.44 | 11.80 | .00 | ||

| Separate | .12 | .62 | .01 | .19 | .85 | ||

| Biol. Children | .38 | 1.30 | .02 | .29 | .77 | ||

| Initiator Status | 1.10 | 1.48 | .06 | .75 | .46 | ||

| Rel. Length | −.02 | .01 | −.09 | −1.24 | .22 | ||

| Gender | .65 | 1.25 | .04 | .52 | .61 | ||

| AMT | −.90 | .18 | −.51 | −5.32 | .00 | ||

| CWE | −2.22 | 1.74 | −.09 | −1.28 | .21 | ||

| SWE | .52 | 1.68 | .02 | .31 | .76 | ||

| SWE × AMT | .44 | .17 | .22 | 2.55 | .01 | .46 (.42) |

Note. CWE × AMT = Interaction of CWE and AMT; SWE × AMT = Interaction of SWE and AMT; see Table 2 for other variable descriptions. Model 2 maximum VIF = 3.1, Model 3 maximum VIF = 2.0.

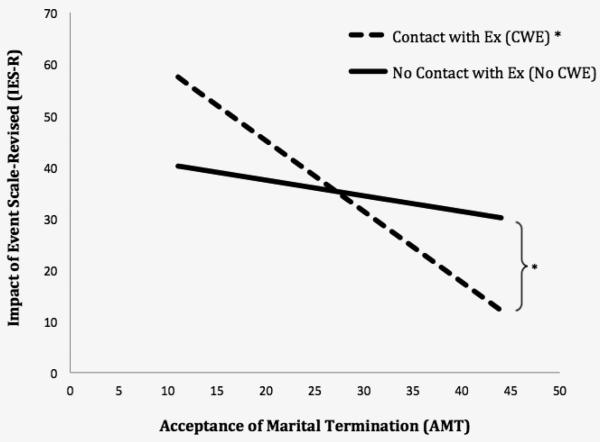

Second, we predicted that CWE and separation acceptance would interact to predict post-separation psychological adjustment. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed a significant interaction effect of CWE × AMT on adjustment, B = -.54, β = -.28, t = -2.37, p = .02, after accounting for both main effects and the main effect of SWE4 (Figure 2; Table 2, Model 2). We first deconstructed the interaction treating CWE as the moderator. As predicted (H2), among participants having CWE, those reporting less separation acceptance reported significantly poorer adjustment than those reporting more separation acceptance, B = -1.37, SE(B) = 0.16, t = -8.62, p < .001. Among participants not having CWE, there was no significant difference in adjustment across levels of separation acceptance, B = -0.31, SE(B) = 0.43, t = -0.72, p = .47. To assess whether participants reporting less/more separation acceptance reported poorer/better adjustment if they were having CWE (relative to not having CWE), we reversed the pairwise deconstruction, treating separation acceptance as the moderator. Data did not support our prediction (H3) that among participants reporting less (-1 SD) separation acceptance, those who were and those who were not having CWE would report significantly different adjustment, B = 3.68, SE(B) = 3.03, t = 1.22, p = .23. As predicted (H4), among participants reporting more (+1 SD) separation acceptance, those having CWE reported significantly better psychological adjustment than those not having CWE, B = -5.95, SE(B) = 2.35, t = -2.53, p = .01.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction of CWE × AMT revealing that CWE and AMT interact to predict psychological adjustment (IES-R). Symbols indicate significant differences. *p < .05.

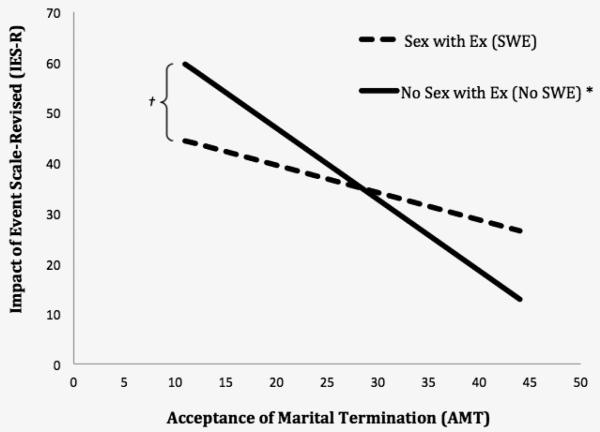

Fourth, we predicted that SWE and separation acceptance would interactively associate with post-separation psychological adjustment. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed a significant interaction effect of SWE × AMT on adjustment, B = 0.44, β = 0.22, t = 2.55, p < .015 (Figure 3; Table 2, Model 3). We first deconstructed the interaction treating SWE as the moderator. As predicted (H5), data revealed that among people not having SWE, those reporting less separation acceptance reported significantly poorer adjustment relative to those reporting more separation acceptance, B = -1.42, SE(B) = 0.16, t = -8.66, p < .001. Notably, less separation acceptance was again associated with worse adjustment, regardless of whether participants reported engaging in SWE. Among people having SWE, there was no effect of separation acceptance on adjustment, B = -0.54, SE(B) = 0.32, t = -1.72, p = .09. To assess whether participants reporting less separation acceptance reported better adjustment if they were having SWE (relative to not having SWE), we reversed the pairwise deconstruction, treating separation acceptance as the moderator. As predicted (H6), among participants reporting less (-1 SD) separation acceptance, those having SWE reported significantly better adjustment than those not having SWE, B = -3.56, SE(B) = 1.82, t = -1.96, p = .05. Among those reporting more (+1 SD) separation acceptance, there were no significant differences across those who were and who were not having SWE, B = 4.30, SE(B) = 2.63, t = 1.63, p = .11.

FIGURE 3.

Interaction of SWE × AMT revealing that SWE and AMT interact to predict psychological adjustment (IES-R). Symbols indicate significant differences. *p < .05, †p = .05.

DISCUSSION

This report explores the roles of nonsexual and sexual contact with an ex-partner (CWE and SWE, respectively) following marital separation, and represents the first study of how individual differences in separation acceptance interact with social context variables to predict post-separation psychological adjustment. Using attachment theory as a guiding framework, we predicted that participants’ separation acceptance (i.e., self-reported feelings of longing for and attachment to an ex-partner) and interpersonal contact with an ex-partner (CWE and SWE) would interact to predict post-separation psychological adjustment. Our primary hypotheses centered on potential mismatches between attachment needs and interpersonal behaviors. Overall, the findings supported several of our hypotheses, and provided a more nuanced account than previous research of how different forms of social contact may interact with ongoing attachment to an ex-partner to predict psychological outcomes.

First, data supported our hypothesis that less separation acceptance would be associated with poorer psychological adjustment (H1). Deconstructions of subsequent statistical models revealed that among people not having CWE and among people having SWE, there was no association between separation acceptance and post-separation psychological adjustment. Thus, the significant correlation between separation acceptance and psychological adjustment was largely driven by people having CWE and people not having SWE.

Data supported our hypothesis that among people having CWE, those reporting less separation acceptance would also report poorer psychological adjustment than those reporting more separation acceptance (H2). We based this prediction on the idea that non-sexual contact may reactivate the attachment system without any provision of felt security. However, we did not find support for our prediction that among people reporting less separation acceptance, those having CWE would report worse adjustment than those not having CWE (H3). As predicted, among people reporting more separation acceptance, those who were having CWE reported better adjustment than those not having CWE (H4).

Taken together, these findings suggest that non-sexual contact with an ex-partner is differentially correlated with psychological adjustment depending on the degree to which one has moved on from, or accepted, the end of a relationship. For some people, having nonsexual contact with an ex-partner is unrelated to post-separation psychological adjustment, whereas for others, having non-sexual contact with an ex-partner is associated with better or worse post-separation psychological adjustment. Indeed, our analyses revealed that the participants reporting the best adjustment of all were those reporting more acceptance and having CWE. Because these people are more accepting of their romantic separations, contact with their ex-partners may not threaten their sense of felt security—i.e., nonsexual contact may not activate an attachment need that is unlikely to be satisfied. Furthermore, for people reporting more separation acceptance, a friendly relationship with an ex-partner—someone in whom they have invested a great deal of time and emotional resources—may fulfill the same important social functions as other friendships, such as social support and rewarding social interactions.

These findings also highlight the importance of not assuming that more separation acceptance corresponds uniformly to better psychological adjustment following a marital separation. There are many situations in which a person may have accepted the end of his or her romantic relationship with an ex-partner, but may continue to struggle with the separation. Consider, for example, a person who leaves his partner following an extramarital affair. In this situation, such a person may report having accepted that the relationship is truly over and may avoid contact with his ex-partner, yet continue to experience intrusive thoughts about the separation experience and former relationship. Overall, the observed interaction between CWE and separation acceptance suggests that understanding why people do or do not have CWE is an important issue for future research.

In contrast to our ideas about nonsexual contact with an ex-partner, and based on the idea that sexual contact fulfills a basic attachment need that nonsexual contact (which may arouse an attachment need without fulfilling it) does not, we made a different set of hypotheses regarding sexual contact with an ex-partner (SWE). Data supported our hypothesis (H5) that among people not having SWE, those reporting less separation acceptance would report poorer adjustment than those reporting more acceptance. Also as predicted, among people reporting less separation acceptance, those having SWE reported better adjustment than those not having SWE (H6). This finding fits with our theoretical framework: People who have an attachment need (those lower in separation acceptance) reported better adjustment if they were having this need met (if they were having SWE). We did not hypothesize the converse (i.e., that among people reporting more separation acceptance, those having SWE would report poorer adjustment than those not having SWE), as our theoretical framework suggests that among people reporting more separation acceptance, sexual contact should not provoke or be a reflection of an unmet attachment need.

Why might it be the case that among people reporting less separation acceptance, those having SWE reported better post-separation psychological adjustment than those not having SWE? In addition, how can we explain the dissociation between CWE and SWE in this respect? One explanation is that having SWE—but not CWE—may allow people who remain highly attached to their ex-partners to achieve a state of felt security via attachment processes that are still operating (see Sbarra & Hazan, 2008). This is consistent with previous literature on self-reported motivations for having sex (Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, 2004), which suggests that people endorse attachment anxiety-reducing motivations (e.g., the enhancement of emotional closeness and self-esteem) as often as they endorse physical pleasure motivations for having sex. Thus, in the context of an overt attachment threat such as a romantic separation, having SWE may allow people who are struggling to accept their separations to reduce their anxiety (e.g., Hazan & Zeifman, 1994). For these same people, having CWE may leave an attachment need activated yet unfulfilled, resulting in distress (Sbarra & Emery, 2005). Indeed, our analyses revealed that the participants with the poorest adjustment of all were those reporting less acceptance and not having SWE.

These findings lead us to wonder whether mismatches across the attachment system—such as longing for an ex-partner yet being unable to have intimate contact with him or her—amplify separation-related distress. Indeed, people reporting less separation acceptance and not having SWE—that is, those reporting the largest mismatch between emotional attachment to and interpersonal behavior with an ex-partner—also reported the poorest psychological adjustment. In practical terms, this mismatch hypothesis sheds light on one reason why previous research has failed to reveal a single optimal way to get over a former relationship: Individual differences in attachment to one's former partner may dictate what constitutes a mismatch to begin with and how people respond to such a mismatch. This idea is consistent with previous work showing that among people in a state of elevated attachment anxiety, the degree of relationship dedication does not depend on the degree to which romantic partners help fulfill psychological needs. Slotter and Finkel (2009) found that people reporting more anxiety were likely to remain dedicated to their relationships even if their interactions with their partners were unfulfilling. These findings may help explain why SWE, but not CWE, seemed to benefit our less-accepting participants: Continuing to rely fruitlessly on an ex-partner for the fulfillment of needs is clearly maladaptive, yet less-accepting people may be more likely to persist in precisely this manner.

What are the practical implications of the findings we observed here? Among people having CWE, the difference in magnitude on the IES-R between those reporting more and less separation acceptance was 24.95 points: Those reporting more (+1 SD) separation acceptance reported significantly better psychological adjustment (IES-R = 18.87) than those reporting less (-1 SD) acceptance (IES-R = 43.82). In addition, among people not having SWE, the difference in magnitude on the IES-R between those reporting more and less acceptance was 25.73 points: Those reporting more (+1 SD) acceptance reported significantly better adjustment (IES-R = 19.85) than those reporting less (-1 SD) acceptance (IES-R = 45.58). These differences in IES-R scores allow us to describe the practical significance of the observed results: People with IES-R scores greater than 33 experience considerable functional impairment and considerable interruptions in their day to day life (see Creamer et al., 2003; Weiss & Marmar, 1997). Thus, we can conclude that the people reporting poorer adjustment in our sample were likely experiencing significantly greater impairment as a function of their separation relative to those reporting better adjustment.

The current study should be considered in light of its limitations. First, the modest proportion of the sample that reported engaging in SWE (~22%) is a relative weakness as it limits statistical power. Because SWE is an understudied topic among the recently divorced, future research will benefit from oversampling participants who report having SWE. Second, our index of SWE was a single item, but the construct is undoubtedly more complex than can be captured by a dichotomous yes/no response: A more detailed measure would assess aspects of SWE such as the frequency, type, and valence of sexual contact (e.g., Diamond, in press). Prospective research using multiple measurement methods would provide further insight into the phenomenon of SWE and its associations with psychological adjustment. Third, despite the fact that SWE is an inherently interpersonal construct, we did not collect information on the context in which these sexual encounters occurred. It would be reasonable to expect that how and when ex-partners choose to have sexual contact may be associated with their divorce-related psychological adjustment. Fourth, because the study is cross-sectional, it is impossible to determine the precise ordering of effects. Our theory dictates that relationship-specific variables would predict generalized psychological distress. Although we addressed the issue of bi-directionality to the degree possible given the limitations of these data, we recognize that general distress may also influence relationship-specific processes. Finally, because our sample included only people who had separated relatively recently, our data cannot speak to the longer-term effects of SWE and CWE on adjustment. It is possible that the benefits associated with SWE or CWE that we observed under some conditions could fade or even become detriments over time. For example, although SWE was associated with benefits among people reporting less acceptance in our sample, continuing to have SWE long after a separation might inhibit a person's ability to form new romantic attachments in the future.

CONCLUSION

The present study represents one of the first investigations of how individual differences in attachment to a former partner and social context variables interact to predict psychological adjustment following marital separation. This report extends prior research on interpersonal processes among ex-partners by showing that nonsexual and sexual contact with an ex-partner are not uniformly positively or negatively correlated with psychological adjustment; rather, examining the degree to which one still longs for an ex-partner allows for a more targeted understanding of these associations. Similarly, this report provides evidence that separation acceptance is not uniformly positively or negatively correlated with psychological adjustment, but rather that taking into account social contact with an ex-partner highlights for whom this correlation is meaningful.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging (AG 028454), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 074637), and the National Science Foundation (BCS 0919525) to David Sbarra.

Footnotes

To address the possibility of bi-directionality in the models testing the CWE × AMT and SWE × AMT interaction as predictors of the IES-R, we switched the IES-R and the AMT variables such that the AMT was the outcome variable and the IES-R was a focal and interactive predictor: The models predicting AMT from the SWE × IES-R and CWE × IES-R yielded nonsignificant interaction terms (SWE × IES-R: B = .07, p = .12; CWE × IES-R: B = -.10, p = .15).

See Footnote 1.

The patterns of significance and findings for all regression models do not change when we account for attachment style, as measured by the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Scale (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). The ECR-R is a reliable, widely used, 36-item self-report measure that taps attachment-related avoidance and anxiety in close relationships.

In all analyses in which CWE and its interaction with AMT are of focal interest, we statistically account for SWE, and vice versa. Hence, observed effects for CWE capture nonsexual aspects of ex-partner contact, and observed effects for SWE take into account nonsexual contact.

See Footnote 1.

REFERENCES

- Bogaert AF, Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call V, Sprecher S, Schwartz P. The incidence and frequency of marital sex in a national sample. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:639–652. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. An attachment theory perspective on closeness and intimacy. In: Mashek DJ, Aron A, editors. Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. pp. 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Shaver PR, Vernon ML. Physical, emotional, and behavioral reactions to breaking up: The roles of gender, age, emotional involvement, and attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:871–884. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029007006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Shaver PR, Vernon ML. Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1076–1090. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Morrone-Strupinsky JV. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: Implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:313–395. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Where's the sex in relationship research? Where are the relationships in sex research? In: Stewart S, editor. Let's talk about sex: Multidisciplinary approaches to sexuality. Cape Breton University Press; Sydney, Nova Scotia: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TFC, De Graaf PM, Kalmijn M. Friendly and antagonistic contact between former spouses after divorce: Patterns and determinants. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:1131–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Zeifman D. Sex and the psychological tether. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. Jessica Kingsley; London: 1994. pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science. 2010;330:932. doi: 10.1126/science.1192439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson GC. Attachment to the spouse in divorce: A scale and its application. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1982;44:379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson GC, Holmes WM. Portrait of divorce: Adjustment to marital breakdown. Guilford; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Masheter C. Postdivorce relationships between ex-spouses: The roles of attachment and interpersonal conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, Barber BL. A person-centered approach to the multifaceted nature of young adult sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47:301–313. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanley E. Eight ways to put your ex behind you. Glamour (Smitten Daily Sex and Relationships Blog). Retrieved May. 2010;2:2011. from http://www.glamour.com/sex-love-life/blogs/smitten/2010/10/8-ways-to-put-your-ex-behind-y.html. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA. Predicting the onset of emotional recovery following nonmarital relationship dissolution: Survival analyses of sadness and anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:298–312. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA, Emery RE. The emotional sequelae of nonmarital relationship dissolution: Analysis of change and intraindividual variability over time. Personal Relationships. 2005;12:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA, Emery RE. Deeper into divorce: Using actor-partner analyses to explore systemic differences in coparenting conflict following custody dispute resolution. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:144–152. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA, Hazan C. Coregulation, dysregulation, self-regulation: An integrative analysis and empirical agenda for understanding adult attachment, separation, loss, and recovery. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12:141–167. doi: 10.1177/1088868308315702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CS, Kenny DA. Cross-sex friends who were once romantic partners: Are they platonic friends now? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2000;17:451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Hazan C, Bradshaw D. Love as attachment: The integration of three behavioral systems. In: Sternberg RJ, Barnes M, editors. The Psychology of Love. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1988. pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. The dissolution of romantic relationships: Factors involved in relationship stability and emotional distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Slotter EB, Finkel EJ. The strange case of sustained dedication to an unfulfilling relationship: Predicting commitment and breakup from attachment anxiety and need fulfillment within relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:85–100. doi: 10.1177/0146167208325244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmann SS, MacDonald G, Wilson AE. On the rebound: Focusing on someone new helps anxiously attached people let go of their ex-partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:1382–1394. doi: 10.1177/0146167209341580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Amato PR. Predictors of divorce adjustment: Stressors, resources, and definitions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:655–668. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale-revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD: A handbook for practitioners. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]