Abstract

Background

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an important cause for diarrhea in children in developing countries and foodborne outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in industrialized nations. To improve understanding of the basic biology of Cyclospora spp. and development of molecular diagnostic tools and therapeutics, we sequenced the complete apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis.

Methods

The genome of one Chinese C. cayetanensis isolate was sequenced using Roche 454 and Illumina technologies. The assembled genomes of the apicoplast and mitochondrion were retrieved, annotated, and compared with reference genomes for other apicomplexans to infer genome organizations and phylogenetic relationships. Sequence variations in the mitochondrial genome were identified by comparison of two C. cayetanensis nucleotide sequences from this study and a recent publication.

Results

The apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis are 34,155 and 6,229 bp in size and code for 65 and 5 genes, respectively. Comparative genomic analysis showed high similarities between C. cayetanensis and Eimeria tenella in both genomes; they have 85.6 % and 90.4 % nucleotide sequence similarities, respectively, and complete synteny in gene organization. Phylogenetic analysis of the genomic sequences confirmed the genetic similarities between cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. and C. cayetanensis. Like in other coccidia, both genomes of C. cayetanensis are transcribed bi-directionally. The apicoplast genome is circular, codes for the complete machinery for protein biosynthesis, and contains two inverted repeats that differ slightly in LSU rRNA gene sequences. In contrast, the mitochondrial genome has a linear concatemer or circular mapping topology. Eight single-nucleotide and one 7-bp multiple-nucleotide variants were detected between the mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis from this and recent studies.

Conclusions

The apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis are highly similar to those of cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. in both genome organization and sequences. The availability of sequence data beyond rRNA and heat shock protein genes could facilitate studies of C. cayetanensis biology and development of genotyping tools for investigations of cyclosporiasis outbreaks.

Keywords: Cyclospora, Genomics, Genome, Apicoplast, Mitochondria, Molecular diagnosis

Background

Human cyclosporiasis is caused by Cyclospora cayetanensis. It is endemic in many developing countries, responsible for significant morbidity in children and AIDS patients [1, 2]. It is also a major cause of foodborne diarrheal illnesses in industrialized nations, especially in North America. Since the mid-1990s, numerous outbreaks of cyclosporiasis have occurred in the United States and Canada, mostly associated with fresh produce imported from Mexico and Central America [2, 3]. The lack of molecular diagnostic tools for case-linkage and trace-back investigations of outbreaks has hampered responses from public health and regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This was exemplified in two recent large multistate outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in 2013 and 2014 in the United States [4] (http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/index.html).

One major reason for the lack of molecular diagnostic tools and poor understanding of the basic biology of C. cayetanensis is the limited availability of nucleotide sequences from the parasite. At the end of 2014, among the ~500 entries of Cyclospora sequences in GenBank, almost all of them were from the rRNA (SSU rRNA, 5.8S rRNA, ITS-1, and ITS-2) and 70 kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) genes. The conserved sequence nature of rRNA and HSP70 genes and intra-isolate variations among different copies of ITS-1 and ITS-2 make the development of genotyping tools for the parasite difficult [5–9]. There is a need for genomic sequencing to identify polymorphic markers and promote biologic studies of C. cayetanensis [10].

Apicoplasts and mitochondria are two important intracellular organelles of apicomplexan parasites [11]. The apicoplast is the result of secondary endosymbiosis by ancient apicomplexan parasites, and harbors metabolic pathways that are necessary for the survival of parasites but are very distinct from those of host species [12]. Likewise, mitochondria play key roles in energy metabolism in apicomplexan parasites [11]. Most apicomplexan parasites, with the notable exception of Cryptosporidium spp., have both apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes. Because of the prokaryotic origins and biological importance of both apicoplasts and mitochondria, they have been widely used as drug targets against apicomplexan parasites [12–15]. The non-recombining and co-inherited nature of apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes has recently been used in the development of barcoding tools for tracking worldwide migration of Plasmodium spp. [16–18]. Even at the species level, a recent barcoding study of Eimeria spp. has shown that partial mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) sequences are more reliable species-specific markers than complete nucleic SSU rRNA sequences, as they provide more synapomorphic characters [19]. The near complete genome of C. cayetanensis has been published recently [20].

As there are no data on the apicoplast genome and only partial data on the mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis, we have characterized in this study the complete apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of an isolate from China. Data generated have shown a close relatedness in apicoplast and mitochondrial genomic sequences between C. cayetanensis and cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. and nucleotide sequence polymorphism in mitochondrial genomes between the isolate in this study and the one in the recent publication. These sequence data should be useful in improving our understanding of the biology of C. cayetanensis and developing advanced molecular detection tools.

Methods

DNA preparation, sequencing and de novo assembly

DNA was extracted from a C. cayetanensis specimen collected in July 2011 from a patient in Kaifeng, Henan, China. The identification of C. cayetanensis was done by acid-fast microscopy and confirmed by PCR and sequence analyses of the SSU rRNA gene as previously described [5]. DNA was extracted from sucrose and cesium chloride gradient-purified oocysts using the QIAamp®DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The genome of C. cayetanensis was sequenced using the Roche 454 GS-FLX Titanium (Roche, Branford, CT), with average read lengths of 400–450 bp. Supplemental 100 × 100 bp paired-end sequencing was completed using the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA). After sequencing, 454 sequence reads were assembled using Roche Newbler (gsAssembler 2.3). Illumina reads were trimmed using clc_quality_trim within the CLC Assembly Cell v 4.1.0 (http://www.clcbio.com/) with minimum quality score of 20 and minimum read length of 70. Trimmed reads were assembled de novo with the clc_assembler of the CLC Assembly Cell. Contigs for C. cayetanensis apicoplast and mitochondrion genes were identified by blasting the assemblies against the GenBank database.

PCR confirmation

PCR amplification and sequencing of the amplicons were used to confirm the inverted repeats in the plastid genome. Two pairs of primers were used to amplify the regions that join the inverted repeat to the main body of the apicoplast. The primer sets were F1: 5′-AGT CGC TAA GTA GCC AAG TTT-3′ and R1: 5′-TTG TCT TGC CTG TGC TAT AGT AAT-3′, and F2: 5′- ACT ACA TCA ACG GCT AAC T-3′ and R2: 5′-GTA CGA GAG GAC CAA AGA AA-3′, which targeted a 634 (between rps4 and LSU rRNA genes) and 743 bp fragment (between ycf24 and LSU rRNA genes), respectively. The reactions contained 1 μl of DNA, 1× GeneAmp PCR buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 1.5U of GoTaq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), 250 μM dNTPs (Promega), 3 mM MgCl2, 250 nM of each primer, and 400 ng/μl of non-acetylated bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The amplification was performed on a GeneAmp PCR 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems), consisting of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The secondary PCR products were detected by 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis, and sequenced in both directions using the BigDye Terminator V3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Genome annotation and comparison

As the apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis were in complete synteny with those of Eimeria spp., we used the Rapid Annotation Transfer Tool (RATT) [21] to transfer the annotations from the E. tenella apicoplast genome (AY217738) and E. dispersa mitochondrion genome (KJ608416). Potential genes and open reading frames (ORFs) were also identified using GeneMark [22]. The annotation was then manually improved by comparing the predicted ORFs and RATT annotations.

Detection of sequence variations

The 454 and Illumina sequence reads were mapped to reference genomes and assembled sequence contigs using the CLC Genomics Workbench 7.0.3 (http://www.clcbio.com/). The probabilistic variant detection tool in the software package was used to detect single nucleotide variations (SNVs) among mapped reads, using the parameters of min coverage 10, probability 90, required variant count 2, and all other filters unchecked. In-house perl scripts were developed to generate SNV data for display. The assembled apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes were further compared with the corresponding reference genomes using Nucmer within the MUMmer package [23].

Phylogenetic analysis

Full genome sequences for apicoplasts and mitochondria of other apicomplexans were extracted from GenBank and aligned with C. cayetanensis sequences by using the sequence alignment function within the CLC Genomics Workbench 7 (http://www.clcbio.com/). Poorly aligned positions in the alignments were eliminated by using Gblocks [24]. The maximum likelihood phylogenies of these sequences were inferred from the data using the CLC Genomics Workbench under the general time reversible model of nucleotide substitution. The confidence of the cluster formation was assessed by using bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

Nucleotide sequence data from the whole genome sequencing, including the SRA data and assembled contigs, were submitted to NCBI BioProject PRJNA256967. Sequences of the annotated apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KP866208 and KP796149.

Results

Genome coverage and copy numbers

Altogether, 46.8 Mb of nucleotides in 4,811 assembled contigs (N50 = 55,741 bp) were obtained from the whole genome sequencing by 454 and Illumina technologies. Blast analysis of the sequences identified sequences of the complete apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis. Results of contig assembly and read mapping indicated the ratio of the copy numbers of nucleic and apicoplast genomes was 1.00:1.08 (average coverage = 205.03 and 220.62 folds for nucleic and apicoplast genomes, respectively). In contrast, the copy number ratio for nucleic and mitochondrial genomes was 1.00:513.25 (average coverage = 205.03 and 10,5231.79 folds for nucleic and mitochondrial genomes, respectively).

Apicoplast genome

Genome organization

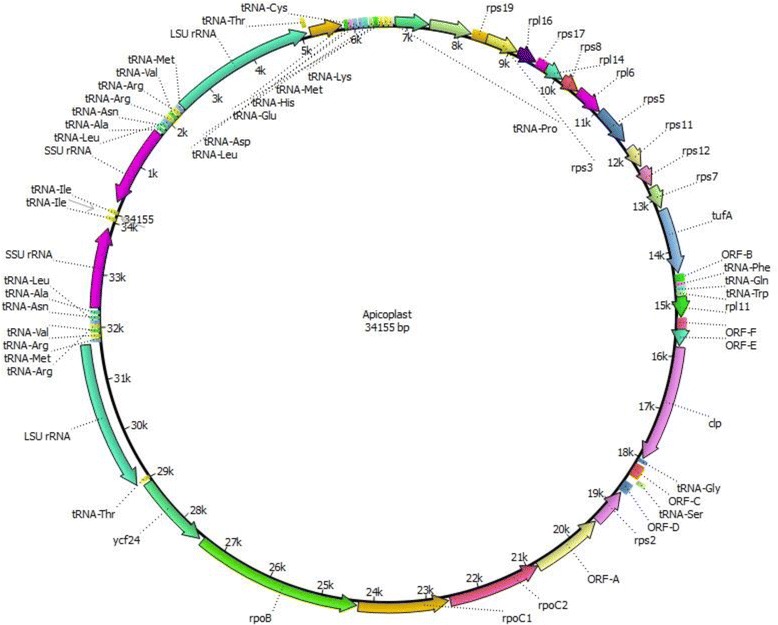

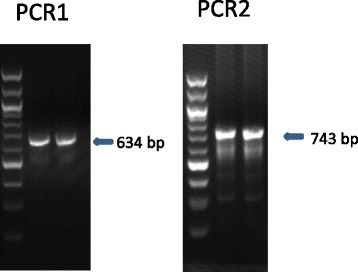

The apicoplast genome is 34,155 bp in size with the following base composition: A (40.28 %), T (37.76 %), C (10.79 %) and G (11.16 %), with an overall AT content of 78.04 %. It contained two inverted repeats (IR). Each IR unit is 5,244 bp in length and contains genes coding for an SSU rRNA, an LSU rRNA, and nine tRNAs (Fig. 1). PCR with one primer in the repeat and the other primer in the non-repeat part of the apicoplast sequence amplified the two regions joining the IR to the main body of the apicoplast (Fig. 2). The joint sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing, which yielded sequences identical to those from the whole genome sequencing. PCR amplification of the sequence between the closer ends of the two IRs was not successful probably because of the inverted nature of the repeat units. However, a search of reads from Roche 454 sequencing revealed that there are 33 bp between the closer ends of the two IRs. This allowed the construction of the full circular apicoplast genome of C. cayetanensis. The presence of two IRs was also confirmed by mapping of sequence reads to the assembled contigs, as the two IRs differed by eight nucleotides in a 58-bp region of the LSU rRNA gene (Table 1). The relative placement of the two slightly different IR units in the circular apicoplast genome was not clear.

Fig. 1.

Map of the apicoplast genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis

Fig. 2.

PCR analysis of the regions joining the inverted repeat (IR) and the remainder of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast. A 634 bp and a 743 bp fragment covering the joints of the IR and the remainder of the apicoplast were amplified by using PCR with the one primer in the repeat and the other primer in the other part of the apicoplast. The molecular weight marker is a100bp DNA ladder

Table 1.

Sequence differences between two inverted repeats (IR) of the apicoplast genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis a

| Reference position | Reference | Alleleb | Count | Coverage (fold) | Allele frequency (%) | Mean read quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4096 | C | - | 272 | 413 | 65.86 | 28.94 |

| 4098 | A | C | 265 | 414 | 64.01 | 30.84 |

| 4100 | A | G | 271 | 420 | 64.52 | 30.46 |

| 4117 | G | A | 300 | 462 | 64.94 | 30.19 |

| 4136 | G | A | 276 | 417 | 66.19 | 31.3 |

| 4142 | A | T | 241 | 380 | 63.42 | 27.8 |

| 4149 | C | T | 210 | 340 | 61.76 | 30.39 |

| 4153 | A | T | 198 | 324 | 61.11 | 29.71 |

| 29970 | T | A | 171 | 302 | 56.62 | 30.46 |

| 29974 | G | A | 180 | 320 | 56.25 | 31.23 |

| 29981 | T | A | 218 | 358 | 60.89 | 28.16 |

| 29987 | C | T | 249 | 390 | 63.85 | 30.38 |

| 30006 | C | T | 275 | 418 | 65.79 | 30.59 |

| 30023 | T | C | 241 | 388 | 62.11 | 30.16 |

| 30025 | T | G | 240 | 387 | 62.02 | 30.48 |

| 30027 | G | - | 246 | 385 | 63.90 | 28.14 |

aThe variable fragment is located in a 58-bp region (5′- CTATAACGGTCCAAAGGTAGCGAAATTCCTTGTCGGGTAAGTTCCGACCTGCACGAA-3′) of the LSU rRNA gene of each IR

bDash indicates a nucleotide deletion

Gene organization

The annotation of the sequences indicated that there are 65 genes coded by the apicoplast genome, including 4 rRNA genes, 28 protein-coding genes, and 33 tRNA genes for all 20 amino acids. The protein-coding genes include 6 genes for ribosomal protein large subunit (rpl), 10 genes for ribosomal protein small subunit (rps), 3 genes for RNA polymerase (rpo), 6 genes for hypothetical proteins, and 1 gene each for elongation factor Tu (tufA), ATP-dependent Clp protease (clpC) and putative ABC transporter (ycf24). The C. cayetanensis apicoplast has almost all the genes encoded in the E. tenella apicoplast genome except rpl36, which is truncated. Similarly, the orf-D gene of C. cayetanensis codes for only 70 amino acids in length, which is 29 amino acids shorter than that of E. tenella. orf-A codes for a protein similar to the DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit. The organization of these genes is shown in Fig. 1.

Usage of start and stop codons

Rpl2, rps11 start with the codon ATT and rpl11 starts with codon ATA. The start codon for rpoC1 is unclear. By comparing the same gene in E. tenella, the corresponding start codon of rpoC1 in Cyclospora is TTT. The start codon for all remaining genes is ATG. A total of 20 in-frame TGAs coding for tryptophan (W) are present in 14 genes in the apicoplast genome. Because of the unavailability of TGA as a stop codon, most apicoplast genes in C. cayetanensis end with the codon TAA, with three genes (rpl2, orf-C, and rpoB) using TAG (data not shown).

Genetic similarity to other apicomplexans

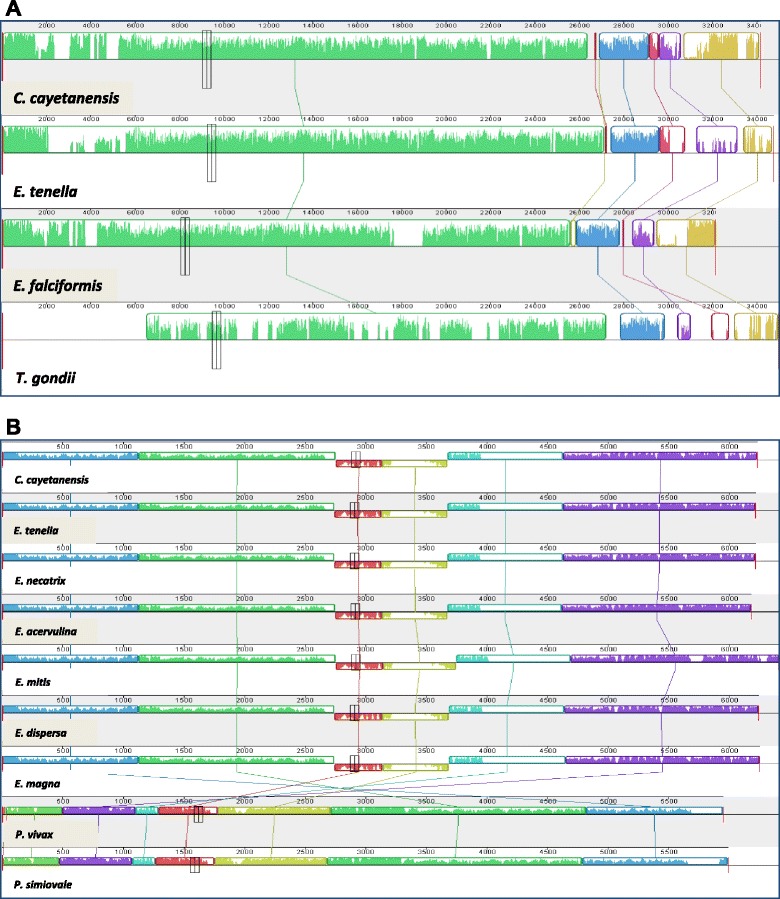

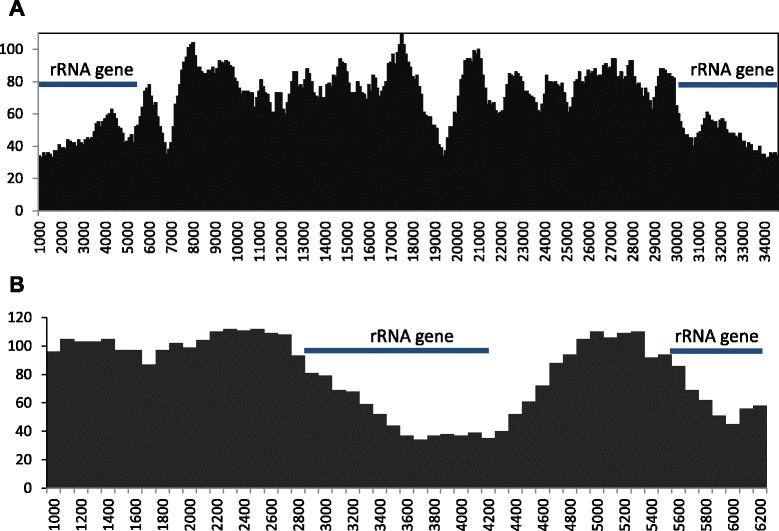

A Blast search of the NCBI database with the C. cayetanensis apicoplast sequence showed that the sequence was most similar to the apicoplast genome of E. tenella (access no. AY217738.1). Genome sequence alignments showed that the C. cayetanensis apicoplast genome has complete gene synteny to the apicoplast genome of E. tenella and other Eimeria spp. and good synteny to the genome of T. gondii (Fig. 3a). Aligning the assembled apicoplast genome sequence to that of the E. tenella apicoplast genome with NUCmer resulted in a single alignment that covers 99.85 % of the apicoplast genome, confirming the synteny between the two genomes. The identity between the two genomes in the aligned regions was 85.6 %. The sequence divergence between the two genomes was mostly 8–10 % as calculated in a sliding window of 1,000 bp in sequence read mapping. However, much lower sequence differences were seen in rRNA genes within the two IR units (Fig. 4a). SNV analysis by read mapping did not identify any intra-isolate sequence polymorphism beyond what was described between the two IRs.

Fig. 3.

Synteny in gene organizations between Cyclospora cayetanensis and Eimeria spp. in the apicoplast (a) and mitochondrial (b) genomes. The color blocks are conserved segments of sequences internally free from genome rearrangements, whereas the inverted white peaks within each block are sequence divergence between the C. cayetanensis genome and other genomes under analysis

Fig. 4.

Distribution of SNVs along apicoplast (a) and mitochondrial (b) genomes in comparison with those of Eimeria tenella. The number of SNVs was calculated by mapping of sequence reads to the reference E. tenella genome in a sliding window of 1,000 bp with 100-bp steps

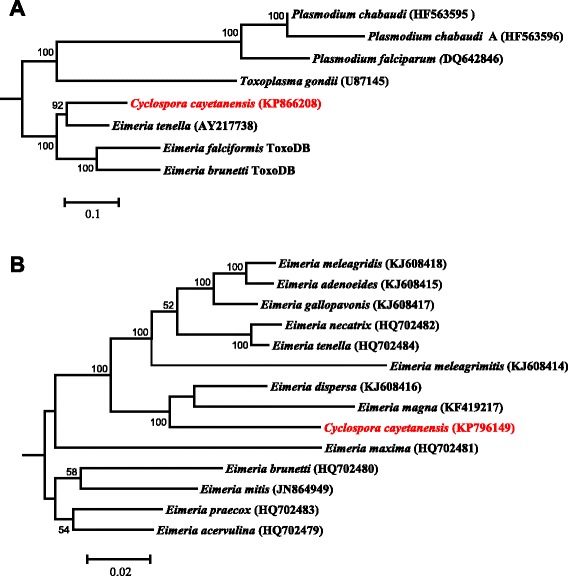

In a maximum likelihood analysis of apicoplast genome sequences from apicomplexans, C. cayetanensis, E. tenella, E. falciformis, and E. brunetti formed one clade that was divergent from T. gondii and Plasmodium spp. Within the clade formed by Cyclospora and Eimeria, C. cayetanensis clustered together with E. tenella, confirming the genetic similarity between the two species based on direct sequence comparison and gene annotations (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of apicoplast (a) and mitochondrial (b) genomes. The phylogeny was inferred under the general time reversible model of nucleotide substitution in the CLC Genomics Workbench with the Gblocks-processed aligned regions. The numbers at nodes indicate bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates. The scale bars indicate the estimated substitutions per site

Mitochondrial genome

Genome organization and gene content

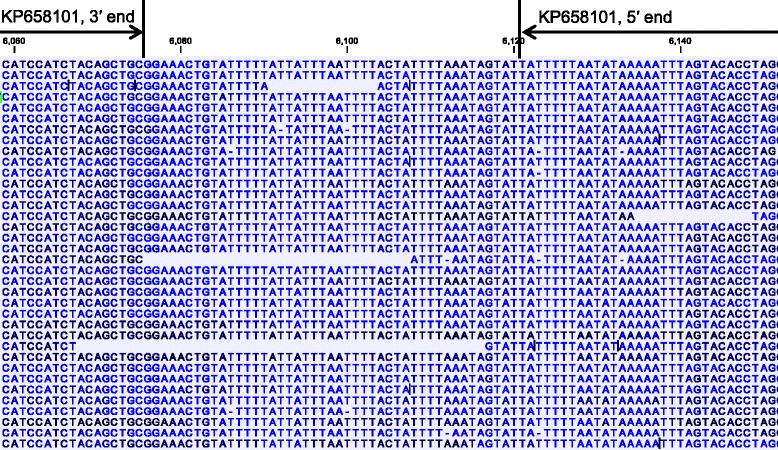

Single contigs containing the complete mitochondrion genome were identified by Blast analysis of the assembly of sequences from the whole genome sequencing project. The overlapped ends of the contigs generated in different genome assembly efforts indicated that the mitochondrion genome was either circular or concatemeric. This was supported by read mapping at the joint region between two mitochondrial genome units (Fig. 6). Each mitochondrial genome unit is 6,229 bp in length with an AT content of 66.59 %. It codes the complete genes for cytb, cox1, and cox3, and fragments of the SSU rRNA and LSU rRNA, and has the same organization reported recently [20]. The full mitochondrial genomic sequence is 45 nucleotides longer than the published genome KP658101 (Fig. 6). Among the 45 nucleotides, 30 align with the 3′ terminus sequences from Eimeria spp. proposed by Ogedengbe and colleagues [20], with the conserved palindromic sequence ‘CTGTTATTTTGTC’ replaced by the sequence ‘CTGTATTTTTATTATTTAATTTTAC’. The remaining 15 nucleotides ‘TATTTTAAATAGTAT’ is upstream of the 21-bp A/T-only region in C. cayetanensis, which was suggested to be the beginning of the linear monomeric genome of mitochondria in C. cayetanensis [20]. They align better to the conserved 5′-terminus sequences of Eimeria spp. than the 21-bp A/T-only region. Thus, the published mitochondrial genome KP658101 has 15 and 30 nucleotides missing at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Nucleotide sequences at the joint region of the concatenated mitochondrial genomes of Cyclospora cayetanensis as shown by the result of sequence read mapping. Roche 454 sequence reads were mapped to the assembled C. cayetanensis mitochondrial genome from CHN_HEN01 (KP796149). Altogether, 62,397 of 951,428 reads were mapped to the mitochondrial genome, with the average mapped read length = 516.6 bp and average genome coverage = 5,061.5. Only the partial mapping result at the joint region is shown. Blank spaces between sequences denote borders of sequence reads, whereas colors of nucleotides indicate quality scores (dark nucleotides have higher quality score; minimum score = 30.0). The numbers above nucleotide sequences are positions in the mitochondrial genome (KP796149) from this study. The 3′ and 5′ ends of the mitochondrial genome of Cyclo_CDC_2013 (KP658101) are marked

Genetic similarity to other apicomplexans

Blast analysis indicated that C. cayetanensis has 87–92 % sequence similarities to the mitochondrial genomes of various Eimeria spp. in GenBank, with the highest similarity to the genome in E. dispersa (KJ608416). This was confirmed by direct comparison of the assembled C. cayetanensis and E. tenella genomes by using NUCmer, which showed an overall sequence identity of 90.4 %. Comparison of the mitochondrial genomes of apicomplexans indicated that the C. cayetanensis genome has complete synteny with genomes of Eimeria spp. (Fig. 3b). Analysis of SNV distribution by read mapping along the genome of E. tenella showed that the most conserved regions are nucleotide positions 2,800 to 4,900 and positions 5,400 to the end of the genome, where the rRNA gene fragments are located (Fig. 4b). Phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial genome sequences demonstrated that C. cayetanensis formed a clade with E. dispersa from turkeys and quails and E. magna from rabbits, sister to a clade formed by cecum-infecting Eimeria spp. from chickens and turkeys (Fig. 5b).

Sequence polymorphism in C. cayetanensis genomes

Eight single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and one 7-bp multiple-nucleotide variant (MNV) were detected between the mitochondrial genomes of the C. cayetanensis isolate from this study (CHN_HEN01) and the isolate (Cyclo_CDC_2013 (KP658101) in the published study (Table 2). They are dispersed over the entire mitochondrial genome, including both coding and noncoding regions. Both cox1 and cox 3 genes have two SNVs. The 7-bp MNV near and within SSU9 is reverse-complemental in sequence between the two isolates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequence differences in the mitochondrial genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis between the Chinese isolate CHN_HEN01 (KP796149) and US isolate Cyclo_CDC_2013 (KP658101)

| Nucleotide positiona | Gene or region | Nucleotide in Cyclo_CDC_2013 | Nucleotide in CHN_HEN01 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | SSU/8 | T | A |

| 2007 | cox1 | G | A |

| 2253 | cox1 | G | A |

| 3131 | Intergenic between LSU/12 & SSU/1 | T | A |

| 3964 | Intergenic between LSU/8 & SSU/5 | C | A |

| 4282 | LSU/1 | A | T |

| 4703 | cox3 | C | T |

| 4937 | cox3 | C | T |

| 6085–6091 | Intergenic between SSU/11 & SSU9 and within SSU9 | TAATAAC | GTTATTA |

aAccording to GenBank sequence KP658101

Discussion

In this study, the complete apicoplast genome of C. cayetanensis has been sequenced for the first time. We have also obtained the last 45-bp sequence to complete the mitochondrial genome published recently [20]. The apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis are both highly similar to those of Eimeria spp. in genome sizes and gene contents, with a complete synteny in genome organization. As seen in Eimeria spp. and other apicomplexans, the relatively large apicoplast genome of C. cayetanensis codes for the entire array of machinery needed for the expression of the apicoplast genome, including two copies of SSU rRNA and LSU rRNA, various ribosomal proteins, three RNA polymerases, and tRNAs for all 20 amino acids. Thus, C. cayetanensis should have a functional apicoplast organelle, which as in other apicomplexans likely plays key roles in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, isoprenoids, iron-suffer clusters and heme [12, 25]. Like in other coccidian parasites [26], the TGA codon for tryptophan is common in the apicoplast genome of C. cayetanensis. In contrast, hemosporidians such as Plasmodium spp., Theileria spp., Babesia spp., and Leucocytozoon spp. do not have any in-frame TGA codons in their apicoplast genomes [25, 27]. One in-frame TGA codon was also seen in the mitochondrial cox3 gene in C. cayetanensis.

Phylogenetic analysis of both apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes from a diverse group of apicomplexans supports the close relationship between C. cayetanensis and avian Eimeria spp., thus confirming the results of direct comparison of organelle genome organization and those from previous phylogenetic analyses of the partial nucleic SSU rRNA and HSP70 genes [28–31]. However, some minor differences in results among phylogenetic studies have been observed. In the present study, phylogenetic analyses of the complete apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes both suggest that C. cayetanensis is more closely related to the cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. such as E. tenella and E. necatrix than to the small intestine-infecting avian Eimeria spp. such as E. brunetti. This is in agreement with the results of an analysis of the partial SSU RNA gene [30]. Other analyses of the SSU rRNA gene, however, have shown that C. cayetanensis formed a sister cluster with avian Eimeria spp. [29, 32]. Like in this study, most phylogenetic analyses of the SSU rRNA gene have shown a clear separation of the cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. from the small intestine-infecting Eimeria spp. [19, 29, 30, 32]. A recent analysis of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Eimeria spp. has also shown the formation of separate clusters by the cecum-infecting and small intestine-infecting avian Eimeria spp. [33]. Comparisons of the nucleic genomes of these parasites are needed to better understand the evolutionary position of Cyclospora spp. and the biologic significance of the relatedness between C. cayetanensis and cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp.

The structure of the mitochondrial genome of C. cayetanensis in this study is different from the one proposed recently. Based largely on amplification failures using primers that have worked reliably for various Eimeria spp. and new primers designed based on the assumption of a circular or linear concatenated genome, Ogedengbe and colleagues have suggested recently that C. cayetanensis likely has a linear monomeric genome [20]. This is very differently from the linear concatenated genome of E. tenella identified based on restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis [34]. Results of our genome assembly and sequence mapping indicate that C. cayetanensis probably has the same mitochondrial genome structure as E. tenella. In the published study, the high sequence divergence between Cyclospora and Eimeria near the joint of two mitochondrial genome units was probably responsible for the amplification failures in the analysis of the sequence at the joint for C. cayetanensis.

Some sequence differences have been observed between mitochondrial genomes of this and the published studies. Altogether, there are eight SNVs and one MNV between genomes of the Chinese isolate examined in this study and the 2013 Texas outbreak isolate in the previous report [20]. Four of the SNVs are in the cox1 and cox3 genes. Previously, analysis of the full cox1 and cox3 genes showed no sequence differences among five C. cayetanensis isolates from limited areas (Southeast Asia and United States) [20]. Comparative analysis of the apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes has been used in tracking the spread of P. falciparum and P. vivax [16–18]. With further verifications, this approach can be potentially used in geographic tracking of C. cayetanensis during investigations of cyclosporiasis outbreaks in North America.

With the whole apicoplast and mitochondrial genome sequences available, better intervention measures and diagnostic tools can potentially be developed for C. cayetanensis. The close relatedness between avian Eimeria spp. and Cyclospora spp. indicates that avian Eimeria spp., especially those infecting the cecum, may serve as an alternative model for studying Cyclospora spp. Thus far, there are no feasible animal models for C. cayetanensis [35], and feeding sporulated C. cayetanensis oocysts to human volunteers did not produce any infection [36]. The genetic similarity between avian Cyclospora spp. and Eimeria spp. suggests that many of the drugs used in the treatment of poultry coccidiosis may be effective against C. cayetanensis infection. Other therapeutics specifically targeting the mitochondrial and apicoplast metabolism can be developed [13, 14, 37].

Conclusions

In conclusion, data on the complete apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes of C. cayetanensis have been obtained for the first time. Both genomes are highly similar to those of cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp., and sequence variations in the mitochondrial genome between two Chinese and US C. cayetanensis isolates have been identified. The availability of whole apicoplast and mitochondrial genome sequences would improve our understanding of the biology of C. cayetanensis and facilitate the development of new intervention tools. Further characterization of the genomes of other Cyclospora species and additional C. cayetanensis isolates is needed to improve our understanding of the taxonomic position of Cyclospora spp. and the development of genotyping tools for case linkage and infection/contamination source tracking in outbreak investigations.

Ethics statement

The study was done under Human Subjects Protocol No. 990115 “Use of residual human specimens for the determination of frequency of genotypes or sub-types of pathogenic parasites,” which was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). No personal identifier was associated with the C. cayetanensis specimen at the time of submission for diagnostic service at CDC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31425025 and 31110103901) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Kevin Tang and Yaqiong Guo contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YF and LX conceived and designed the experiments; KT, YG, LZ, LAR, DMR, MAF and NL performed the experiments; KT, YG, SL, and LX analyzed the data; KT, YG, YF and LX wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kevin Tang, Email: kht7@cdc.gov.

Yaqiong Guo, Email: guoyaqiong1987@sina.com.

Longxian Zhang, Email: zhanglongxian8999@foxmail.com.

Lori A. Rowe, Email: ioy0@cdc.gov

Dawn M. Roellig, Email: iyd4@cdc.gov

Michael A. Frace, Email: mff3@cdc.gov

Na Li, Email: nli@ecust.edu.cn.

Shiyou Liu, Email: xgu6@cdc.gov.

Yaoyu Feng, Email: yyfeng@ecust.edu.cn.

Lihua Xiao, Email: lxiao@cdc.gov.

References

- 1.Deodhar L, Maniar JK, Saple DG. Cyclospora infection in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(4):404–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortega YR, Sanchez R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):218–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legua P, Seas C. Cystoisospora and cyclospora. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(5):479–83. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000433320.90241.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abanyie F, Harvey RR, Harris JR, Wiegand RE, Gaul L, Desvignes-Kendrick M, et al. 2013 multistate outbreaks of Cyclospora cayetanensis infections associated with fresh produce: focus on the Texas investigations. Epidemiol Infect. 2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Zhou Y, Lv B, Wang Q, Wang R, Jian F, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cyclospora cayetanensis, Henan, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(10):1887–90. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.101296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulaiman IM, Ortega Y, Simpson S, Kerdahi K. Genetic characterization of human-pathogenic Cyclospora cayetanensis parasites from three endemic regions at the 18S ribosomal RNA locus. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;22:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulaiman IM, Torres P, Simpson S, Kerdahi K, Ortega Y. Sequence characterization of heat shock protein gene of Cyclospora cayetanensis isolates from Nepal, Mexico, and Peru. J Parasitol. 2013;99(2):379–82. doi: 10.1645/GE-3114.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivier C, van de Pas S, Lepp PW, Yoder K, Relman DA. Sequence variability in the first internal transcribed spacer region within and among Cyclospora species is consistent with polyparasitism. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31(13):1475–87. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riner DK, Nichols T, Lucas SY, Mullin AS, Cross JH, Lindquist HD. Intragenomic sequence variation of the ITS-1 region within a single flow-cytometry-counted Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts. J Parasitol. 2010;96(5):914–9. doi: 10.1645/GE-2505.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark EL, Blake DP. Genetic mapping and coccidial parasites: past achievements and future prospects. J Biosci. 2012;37(5):879–86. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinger CM, Nisbet RE, Ouologuem DT, Roos DS, Dacks JB. Cryptic organelle homology in apicomplexan parasites: insights from evolutionary cell biology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16(4):424–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dooren GG, Striepen B. The algal past and parasite present of the apicoplast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:271–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman CD, McFadden GI. Targeting apicoplasts in malaria parasites. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17(2):167–77. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.739158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stocks PA, Barton V, Antoine T, Biagini GA, Ward SA, O’Neill PM. Novel inhibitors of the Plasmodium falciparum electron transport chain. Parasitology. 2014;141(1):50–65. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013001571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nixon GL, Pidathala C, Shone AE, Antoine T, Fisher N, O’Neill PM, et al. Targeting the mitochondrial electron transport chain of Plasmodium falciparum: new strategies towards the development of improved antimalarials for the elimination era. Future Med Chem. 2013;5(13):1573–91. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preston MD, Campino S, Assefa SA, Echeverry DF, Ocholla H, Amambua-Ngwa A, et al. A barcode of organellar genome polymorphisms identifies the geographic origin of Plasmodium falciparum strains. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4052. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigues PT, Alves JM, Santamaria AM, Calzada JE, Xayavong M, Parise M, et al. Using mitochondrial genome sequences to track the origin of imported Plasmodium vivax infections diagnosed in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(6):1102–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyagi S, Pande V, Das A. New insights into the evolutionary history of Plasmodium falciparum from mitochondrial genome sequence analyses of Indian isolates. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(12):2975–87. doi: 10.1111/mec.12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogedengbe JD, Hanner RH, Barta JR. DNA barcoding identifies Eimeria species and contributes to the phylogenetics of coccidian parasites (Eimeriorina, Apicomplexa, Alveolata) Int J Parasitol. 2011;41(8):843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogedengbe ME, Qvarnstrom Y, da Silva AJ, Arrowood MJ, Barta JR. A linear mitochondrial genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis (Eimeriidae, Eucoccidiorida, Coccidiasina, Apicomplexa) suggests the ancestral start position within mitochondrial genomes of eimeriid coccidia. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45(6):361–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otto TD, Dillon GP, Degrave WS, Berriman M. RATT: rapid annotation transfer tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(9) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besemer J, Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W451–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5(2):R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(4):540–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeber F, Feagin JE, Parsons M. The apicoplast and mitochondrion of Toxoplasma gondii. In: Weiss LM, editor. Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan - perspectives and methods. 2nd ed.: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2014. p. 297–350.

- 26.Lang-Unnasch N, Aiello DP. Sequence evidence for an altered genetic code in the Neospora caninum plastid. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29(10):1557–62. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imura T, Sato S, Sato Y, Sakamoto D, Isobe T, Murata K, et al. The apicoplast genome of Leucocytozoon caulleryi, a pathogenic apicomplexan parasite of the chicken. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(3):823–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3712-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Relman DA, Schmidt TM, Gajadhar A, Sogin M, Cross J, Yoder K, et al. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Cyclospora, the human intestinal pathogen, suggests that it is closely related to Eimeria species. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(2):440–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberhard ML, da Silva AJ, Lilley BG, Pieniazek NJ. Morphologic and molecular characterization of new Cyclospora species from Ethiopian monkeys: C. cercopitheci sp.n., C. colobi sp.n., and C. papionis sp.n. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(5):651–8. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye J, Xiao L, Li J, Huang W, Amer SE, Guo Y, et al. Occurrence of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium genotypes in laboratory macaques in Guangxi, China. Parasitol Int. 2014;63(1):132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monteiro RM, Richtzenhain LJ, Pena HF, Souza SL, Funada MR, Gennari SM, et al. Molecular phylogenetic analysis in Hammondia-like organisms based on partial Hsp70 coding sequences. Parasitology. 2007;134(Pt 9):1195–203. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao GH, Cong MM, Bian QQ, Cheng WY, Wang RJ, Qi M, et al. Molecular characterization of Cyclospora-like organisms from golden snub-nosed monkeys in Qinling Mountain in Shaanxi province, northwestern China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogedengbe ME, El-Sherry S, Whale J, Barta JR. Complete mitochondrial genome sequences from five Eimeria species (Apicomplexa; Coccidia; Eimeriidae) infecting domestic turkeys. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:335. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hikosaka K, Nakai Y, Watanabe Y, Tachibana S, Arisue N, Palacpac NM, et al. Concatenated mitochondrial DNA of the coccidian parasite Eimeria tenella. Mitochondrion. 2011;11(2):273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eberhard ML, Ortega YR, Hanes DE, Nace EK, Do RQ, Robl MG, et al. Attempts to establish experimental Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in laboratory animals. J Parasitol. 2000;86(3):577–82. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0577:ATEECC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alfano-Sobsey EM, Eberhard ML, Seed JR, Weber DJ, Won KY, Nace EK, et al. Human challenge pilot study with Cyclospora cayetanensis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(4):726–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saremy S, Boroujeni ME, Bhattacharjee B, Mittal V, Chatterjee J. Identification of potential apicoplast associated therapeutic targets in human and animal pathogen Toxoplasma gondii ME49. Bioinformation. 2011;7(8):379–83. doi: 10.6026/97320630007379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]