Abstract

Prior research has established that adolescents’ perceptions of family belonging are associated with a range of well-being indicators and that adolescents in stepfamilies report lower levels of family belonging than adolescents in two-biological-parent families. Yet, we know little regarding what factors are associated with adolescents’ perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies. Guided by family systems theory, the authors addressed this issue by using nationally representative data (Add Health) to examine the associations between family characteristics and adolescents’ perceptions of family belonging in stepfather families (N = 2,085). Results from structural equation models revealed that both the perceived quality of the stepfather–adolescent relationship, and in particular the perceived quality of the mother–adolescent relationship, were the factors most strongly associated with feelings of family belonging.

Keywords: family relations, stepfamilies, adolescence

Children are increasingly likely to spend at least part of their childhood in a stepfamily because of high rates of divorce, nonmarital childbearing, and remarriage. Although it is difficult to get precise counts of their prevalence (Pryor, 2014), estimates suggest that over 10% of all two-parent families in the United States are married or cohabiting stepfamilies (Kreider & Ellis, 2011; Teachman & Tedrow, 2008) and that approximately 25% of all U.S. children will spend at least some time in a married stepfamily (Bumpass, Raley, & Sweet, 1995). The implications of stepfamily formation for children’s well-being are of concern given research indicating that children in stepfamilies generally have lower well-being than children in two-biological-parent households and, on average, show little or no advantage over children in single-parent households (Amato, 2010). Studies comparing children in different family structures, however, tend to emphasize the deficits of stepfamilies rather than give attention to factors that promote positive stepfamily functioning (Coleman, Ganong, & Fine, 2000; Sweeney, 2010).

One aspect of stepfamily functioning that is receiving increased consideration is the quality of parent–child ties within stepfamilies (King, 2009; King, Thorsen, & Amato, 2014; Sweeney, 2010). Increased efforts to understand the factors that promote ties between children and their mothers and stepfathers is not surprising given that the quality of parent–child ties is associated with child well-being in both two-biological-parent families (Videon, 2005) and stepfamilies (King, 2006; Pryor & Rodgers, 2001). Studies suggest that the extent to which children feel they “belong” to the family is also associated with child well-being (e.g., Cavanagh, 2008), though we know little regarding what factors contribute to children’s perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies.

In the current study we used nationally representative data on adolescents in stepfather families from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth), with the primary aim of examining predictors of family belonging among children in stepfamilies. Guided by family systems theory, we paid particular attention to how perceptions of family belonging are related to the quality of ties between family members. We focused on stepfather families because the vast majority of children living in stepfamily households reside with a stepfather rather than a stepmother (Stewart, 2007). Families in which children reside with their father and a stepmother comprise a very select group whose members sometimes face financial, employment, and/or emotional difficulties, reflecting the fact that the route to father residence is very different from the more common occurrence of mother residence after separation (Greif, 1997). Our study was limited to married stepfathers because adolescents in the Add Health study living with mothers and cohabiting partners were not asked about their relationships with stepfathers. Stepfamilies in which the parents began as cohabiting partners but later married were included in the present study. Stepmother households and cohabiting stepfamilies likely differ in important ways from married stepfather families (King, 2007; Nock, 1995) and deserve attention in future research.

Our study focused on children during adolescence, a crucial point in the life course for accomplishing key developmental tasks and avoiding risky behaviors that can lead to poor outcomes that often persist well into adulthood. As children enter adolescence, many families experience declines in parental involvement, supervision, and control and increases in parent–child conflict (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2000). These processes may be exacerbated in stepfamilies, indicating a need to better understand the correlates of positive stepfamily functioning during this critical time period.

Background

As Maslow (1954/1970) long ago argued, individuals have a basic psychological need to feel they belong, in addition to needing love and affection from other individuals (see also Baumeister & Leary, 1995). For children, families—and parents in particular—can help meet this need by providing love and affection. In addition, family members can create a home environment that helps children feel like they belong to this larger family group. Alternatively, negative home environments and relationships can interfere with feelings of family belonging, with attendant negative consequences for children’s well-being.

Several studies have reported that children living in two-biological-parent families report higher levels of family belonging than children living in stepfamilies (Brown & Manning, 2009; Cavanagh, 2008), suggesting that family belonging might be especially challenging to attain in stepfamilies. In a traditional two-parent family, children are biologically related to both parents and all siblings, which likely fosters the feeling that one belongs to this family. Stepfamilies are formed when mothers (or fathers) choose new partners, with children having little say in the matter. The entrance of a stepfather might also be accompanied by the addition of stepsiblings to the household. Mothers and stepfathers need to make a special effort to ensure that children feel they belong to this unit, given that it is based on remarriage rather than biology. Although belonging may be more difficult to attain in stepfamilies, it may be especially important for stepchildren’s well-being and development, given the challenges facing these incompletely institutionalized family forms (Cherlin, 1978; Sweeney, 2010).

Family belonging (Leake, 2007), alternatively referred to as family cohesion/cohesiveness (Crosnoe & Elder, 2004; Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1994; Olson, Sprenkle, & Russell, 1979) family connectedness (Brown & Manning, 2009; Cavanagh, 2008; Resnick et al., 1997), or positive family environment (Amato & Kane, 2011), encompasses a child’s feelings of inclusion within their families: of being understood, having fun together, and of being paid attention to (Goodenow, 1992; Leake, 2005). Measurement of this construct in the extant literature has taken two different approaches. One approach (e.g., Cavanagh, 2008; Leake, 2007), and the approach taken here because it is consistent with our theoretical framework, is to measure family belonging as a construct that is distinct from parent–child relationship quality (the latter usually being indicated by measures of parental involvement and/or children’s feelings of closeness to parents). The second approach is to combine these dimensions of family relationships into a single scale (e.g., Crosnoe & Elder, 2004; Resnick et al., 1997). Critics of the latter approach argue that global measures of family relationships obscure the mechanisms by which family processes influence child well-being and provide evidence that perceptions of family belonging and parent–child relationship quality are separate constructs that are independently associated with child well-being (Cavanagh, 2008; Leake, 2005). As we discuss later in this article, empirical support for the approach we took in this study is provided by analyses indicating that measuring family relationships and belonging as distinct latent variables provided a better fit to our data than did one in which the two sets of measures were combined.

Despite some differences in how family belonging is measured, a growing literature suggests that it is protective against a wide range of negative child outcomes, including emotional distress; suicidal thoughts and behaviors; violence; early sexual debut; negative academic behaviors; and use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana (Cavanagh, 2008; Crosnoe & Elder, 2004; Resnick et al., 1997). Although these studies do not specifically focus on adolescents in stepfamilies, these negative outcomes tend to be more prevalent in stepfamilies (Amato, 2010), and therefore an adolescent’s feelings of family belonging may be even more protective for those living in stepfamilies. Unfortunately, we know little regarding what factors influence children’s perceptions of family belonging. To our knowledge, only Leake (2005, 2007) has specifically examined factors associated with adolescents’ feelings of belonging in stepfamilies, and these findings were based on a small sample (n = 60) of students from high schools and undergraduate university classes in a small Midwestern city.

What Factors Might Promote Perceptions of Family Belonging in Stepfamilies?

Family belonging is a family-level or holistic construct that refers to the entire family, not to any specific relationship. Of course, relationships contribute to people’s feelings of belonging. Thus, although we considered a variety of family characteristics, we paid particular attention to how perceptions of family belonging are related to, and presumably influenced by, relationships within the family. This conceptualization of family belonging and dyadic family relationships as distinct constructs is supported by family systems theory, which treats the family as a non-summative system with properties beyond those of the constituent interpersonal relationships (Broderick, 1993; Hill & Hansen, 1960). According to Becvar and Becvar (1999), “The total system has a unique coherence … adding the parts together will not produce the whole and members are not independent of one another” (p. 32). This alludes to a second key tenet of family systems theory: All parts of the family system are interconnected, and changes or problems in one subsystem affect other subsystems (e.g., Broderick, 1993).

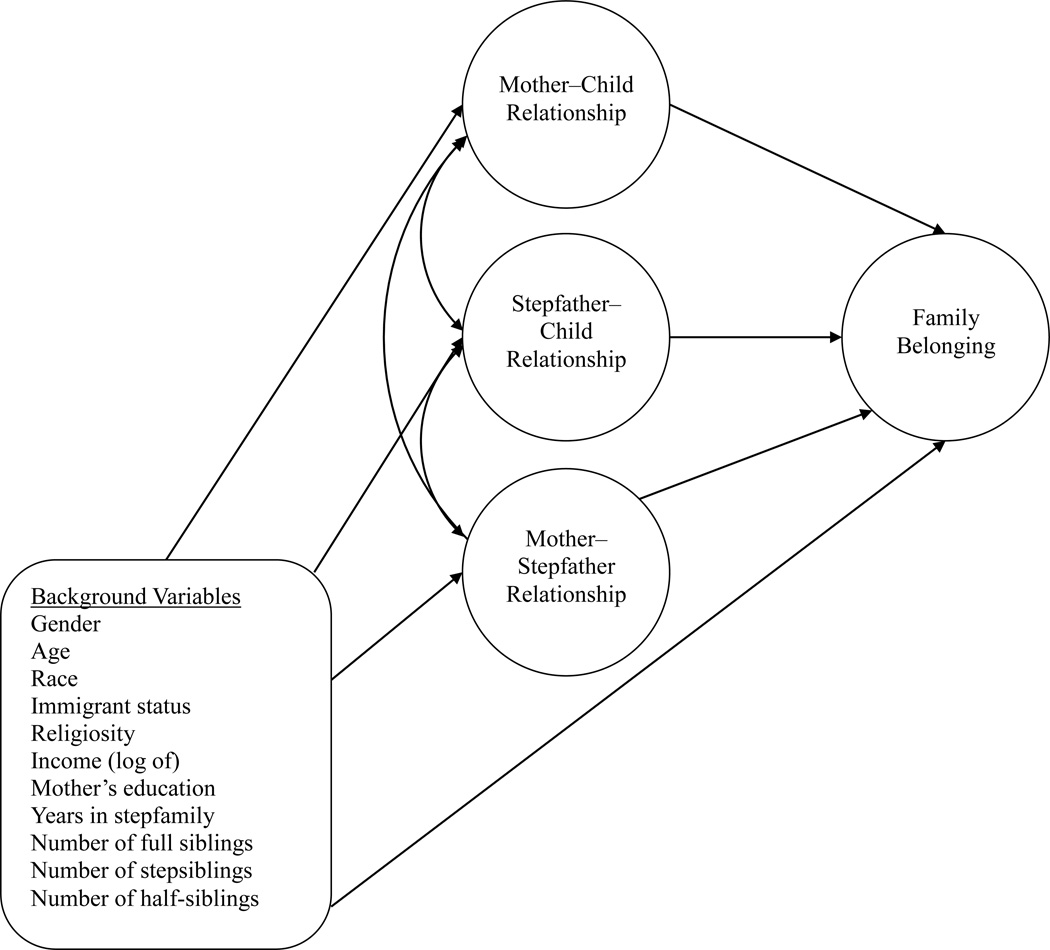

Family systems theory suggests that an adolescent’s perception of family belonging will be influenced by the quality of the relationships that exist between family members. As is shown in Figure 1, the conceptual model we tested reflects this supposition. Mother–child and stepfather–child relationship quality was defined in this study as adolescent’s perceptions of closeness and engagement with each parent in activities and communication. We tested the hypothesis that these relationships are the primary predictors of family belonging in stepfamilies. A positive marital relationship between the mother and stepfather may also enhance the home environment and contribute to feelings of family belonging.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

The influence of other family characteristics (referred to as background variables in Figure 1) is more distal. These variables (e.g., child age and race) may be associated with feelings of family belonging directly, or indirectly, through the more proximate relationship variables. An advantage of a structural equation modeling approach is that it allowed us to examine both the direct effects of family background characteristics and the indirect effects of these factors through other family relationships. By examining only direct effects, prior research has overlooked these potentially important indirect effects.

Leake’s (2007) study of 60 students found the following factors to be significantly associated with feelings of family belonging: a positive relationship with the biological parent, a positive relationship with the stepparent, younger (rather than older) adolescents, and the absence of stepsiblings. Feelings of family belonging were not significantly associated with the adolescent’s gender, age at stepfamily formation, nonresident parent contact, or gender of the resident stepparent. Using nationally representative data, we considered a wider range of factors that may be associated with family belonging in stepfamilies and whether these factors are the same for boys and girls.

Mother–Child Relationship

For adolescents living with their biological mothers and a stepfather, the quality of the mother–child relationship is likely to be a significant predictor of children’s feelings of family belonging. In such families, the mother–child bond is often the only enduring residential bond experienced across the child’s life. Mothers not only play a central role in providing the love and affection that promotes feelings of family belonging (Leake, 2007; Maslow, 1954/1970), but in many cases may also be pivotal in fostering child adjustment in stepfamilies (Smith, 2008). In addition, mothers with close ties to their children may work to ensure they develop positive relationships with the stepfather (Marsiglio, 1992) and other members of the stepfamily, helping to create a more cohesive family environment.

Stepfather–Child Relationship

The entrance of a stepfather into a household influences all other family members and their interaction with one another (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). During this transition, many children maintain close relationships with their mothers and develop close ties with their stepfathers, but others experience deteriorating relationships with their mothers and resist the entrance and authority of the stepfather (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2000; King, 2009). Close stepfather–stepchild relationships can contribute to positive stepfamily functioning and have the potential to enhance children’s feelings of family belonging. Alternatively, problematic relationships with stepfathers may lead adolescents to feel less supported by their family and contribute to a desire to leave home (Aquilino, 1991).

Although we hypothesized that both the mother–child and stepfather–child relationships will be associated with family belonging, which of these relationships will be more strongly associated with perceptions of belonging was less clear. On the one hand, the large variability in the quality of the stepfather–stepchild relationship (King et al., 2014), and the stress and tension experienced during the transition to stepfamily living, suggests that the quality of the stepfather–stepchild relationship may play a larger role in affecting an adolescent’s perception of family belonging. On the other hand, the pivotal role of mothers in enhancing, or detracting from, family functioning and child well-being (Smith, 2008) suggests that the quality of the mother–child relationship will have the most influence on feelings of family belonging. The quality of the stepfather–child relationship may also have less bearing on adolescent feelings of family belonging to the extent that adolescents do not consider the stepfather to be a member of their “family.” Children in stepfather families usually consider their biological mother to be a member of their family, but children vary with regard to whether, and how, they consider stepfathers to be family members (Fine, Coleman, & Ganong, 1998; Thorsen & King, 2014). Consistent with this premise, Leake (2007) found that adolescent perceptions of family belonging were more strongly associated with resident biological parent–child ties than with stepparent–child ties.

Mother–Stepfather Relationship

Many studies have reported a positive link between marital quality and the (step) parent–child relationship (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; King, 2006). A positive marital relationship between the mother and stepfather may also enhance the home environment and contribute to feelings of family cohesiveness. Parents in supportive marriages may be more available to respond to children’s needs and be more attuned to supporting each other’s relationships with the children. Conflict and marital disagreements, on the other hand, may interfere with family cohesiveness and contribute to an adolescent’s desire to leave home to escape an unpleasant environment.

Family and Child Characteristics

We considered a number of background variables that may be associated with feelings of family belonging, directly or indirectly, through the more proximate relationship variables. With respect to gender, several studies have reported that boys have better relationships with stepfathers than do girls (Jensen & Shafer, 2013) and that adolescent girls in stepfamilies are more likely than boys to disengage from their families (Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998). For exploratory purposes, we also assessed the moderating role of child gender, testing whether the factors that predict family belonging differ for boys and girls.

With respect to age, parental involvement and closeness to parents tend to decline during adolescence (King, 2009; Stewart, 2005). A few studies have examined racial/ethnic differences in stepfamily relationships, but these have yielded mixed findings. Some studies suggest that the stressful conditions and disadvantages often faced by racial/ethnic minorities create challenges to successful stepfamily functioning, which could hinder feelings of family belonging, but others suggest that stepfathers may be more easily integrated into the household in racial/ethnic minority families, thereby fostering family cohesiveness (Coleman, Ganong, & Rothrauff, 2006; King et al., 2014; Stewart, 2007). Little is known about stepfamily relationships in immigrant families. The process of migration and differences between parents born and reared in another country and their U.S.–born children can be a source of intergenerational conflict (Chilman, 1993), suggesting that family cohesion might be harder for these families to attain.

Most religions encourage parents to be actively involved in the lives of their children, and religious institutions sponsor activities that bring family members together, potentially fostering feelings of family belonging (King, 2010). Although we know of no research that has directly examined the role of religiosity in perceptions of family belonging, recent research has found that adolescent religiosity is associated with reporting more positive ties to both mothers and stepfathers (King et al., 2014).

Income and parental education are generally associated with higher levels of parental involvement (Amato, 1998), and greater economic resources may reduce stress and enhance feelings of family belonging. The length of time a stepfamily has been together has been found to be associated with closer stepfather–stepchild bonds (Sweeney, 2010), although it is negatively related to marital quality (King et al., 2014). A few studies suggest that the presence of full- and half-siblings, but the absence of stepsiblings, can enhance stepfather–stepchild relationships and stepfamily cohesion (Ganong, Coleman, & Jamison, 2011; King et al., 2014; Leake, 2007).

Method

We used data from the first wave of Add Health. The full sample includes 20,745 adolescents in Grades 7–12 during the 1994–1995 school year and is nationally representative when appropriate sample weights are used. Parent data (n = 17,670) were collected from one parent, usually the resident mother (see Harris et al., 2009, for a detailed description of the data). The analytic sample was confined to adolescents with valid sample weights who reported residing with their biological mother and a married stepfather (n = 2,085).

We relied on structural equation modeling techniques, a particularly appropriate approach for our study given the multiple pathways proposed and the underlying latent constructs outlined in the conceptual model. Analyses were conducted in Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Mplus used a full-information maximum-likelihood technique to deal with missing data. Results are based on weighted data, and all analyses took into account the Add Health sample design (i.e., clustering and stratification).

Measures

The dependent variable family belonging was measured with four observed indicators (α = .74) from the adolescent interview (with five response options, ranging from 1 = very little to 5 = very much): (a) “How much do you feel your family understands you?” (M = 3.53, SD = 1.04), (b) “How much do you feel you want to leave home?” (reverse-coded, M = 3.74, SD = 1.25), (c) “How much do you feel you and your family have fun together?” (M = 3.59, SD = 1.03), and (d) “To what extent do you feel your family pays attention to you?” (M = 3.82, SD = 0.92). (Unless otherwise noted, all variables were created using reports from the adolescent.) Although adolescents, on average, reported fairly high scores on the four indicators of family belonging, moderate variation existed in this measure. Approximately 14% of adolescents disagreed quite a bit or very much with both the statement that their families understand them and that they have fun together, and about 7% felt their families paid little or no attention to them. Sixteen percent of adolescents reported that they would like quite a bit or very much to leave home.

The latent construct mother–child relationship was measured with three scales: (a) mother–child closeness, (b) shared mother–child activities, and (c) mother–child communication. Mother–child closeness consisted of five items rated on a 5-point scale asking youth how close they feel to their mother, how much they feel she cares about them, how much they feel she is warm and loving, how satisfied they are with their communication, and how satisfied they are with their overall relationship (α = .85, M = 4.42, SD = 0.63). An index of activities that adolescents engaged in with their mothers during the previous 4 weeks was the sum of five dichotomous (1 = yes, 0 = no) items including shopping, playing a sport, attending church, seeing a movie, and working on a school project (M = 1.50, SD = 1.06). Communication was the sum of three dichotomous (1 = yes, 0 = no) items regarding whether adolescents talked with their mothers during the previous four weeks about grades, school, or dating or parties (M = 1.69, SD = 1.06). The factor loading for communication on the mother–child relationship latent variable was relatively low (standardized λ = .21). As a check, we ran the main model without communication, using only closeness and activities to create the mother–child relationship latent variable. Results and conclusions were similar to those from the model including communication. Therefore, communication was retained in the model to improve the content validity of the mother–child relationship latent variable.

The items and scales for the stepfather–child relationship latent construct were identical to those for the mother–child relationship: closeness (α = .90, M = 3.86, SD = 0.93), activities (M = 1.15, SD = 1.17), and communication (M = 1.35, SD = 1.03). In preliminary analyses we also created a latent construct for the child’s relationship with the nonresident biological father (identical scales for activities and communication, and one item for closeness), but it was unrelated to perceptions of family belonging and not retained in the final model.

The latent construct mother–stepfather relationship was measured with three observed indicators drawn from the mother interview: (a) current relationship happiness (measured on a 1-to-10 scale, M = 8.50, SD = 1.66), (b) whether the mother and stepfather had talked about separation in the previous year (1 = no, have not talked about separating, 0 = yes, have talked about separating; M = 0.80, SD = 0.40), and (c) how infrequently the mother and stepfather fight (1 = fight a lot, 4 = not at all; M = 2.83, SD = 0.78). Each variable was coded such that a higher score indicated better relationship quality.

The adolescent’s gender was a dichotomous variable with 1 = female (51%) and 0 = male. The adolescent’s age was measured in years (M = 15.39, SD = 1.78). Race/ethnicity was measured as a set of dummy variables for the mutually exclusive categories non-Hispanic White (69%; reference group), non-Hispanic Black (13%), Hispanic (12%), and “other race” (6%). Immigrant family status was categorized with a set of dummy variables: both the adolescent and stepfather were U.S. born (89.6%; reference group), only the adolescent was U.S. born (the stepfather was not; 5.8%), and the adolescent was not U.S. born (the stepfather may or may not have been; 4.6%). The adolescent’s religiosity was measured with a three-item scale incorporating measures of church attendance, the importance of religion to the individual, and participation in other church activities (α = .82, M = 2.46 on a 4-point scale, SD = 0.98).

Income was reported in the parent interview and was transformed using the natural log function (M = 3.50, SD = 1.37). The mother’s educational attainment was reported by mothers (or taken from the adolescent interview when mother reports were missing) and measured continuously with a range from 1 (did not graduate from high school) to 4 (college degree or more; M = 2.52, SD = 0.95). The length of time the adolescent had lived in the stepfamily was measured in years (M = 7.43, SD = 4.61). Three continuous variables indicated the number of full- (M = 0.72, SD = 0.88), step- (M = 0.17, SD = 0.59), and half-siblings (M = 0.63, SD = 0.92) in the household.

RESULTS

Measurement Model

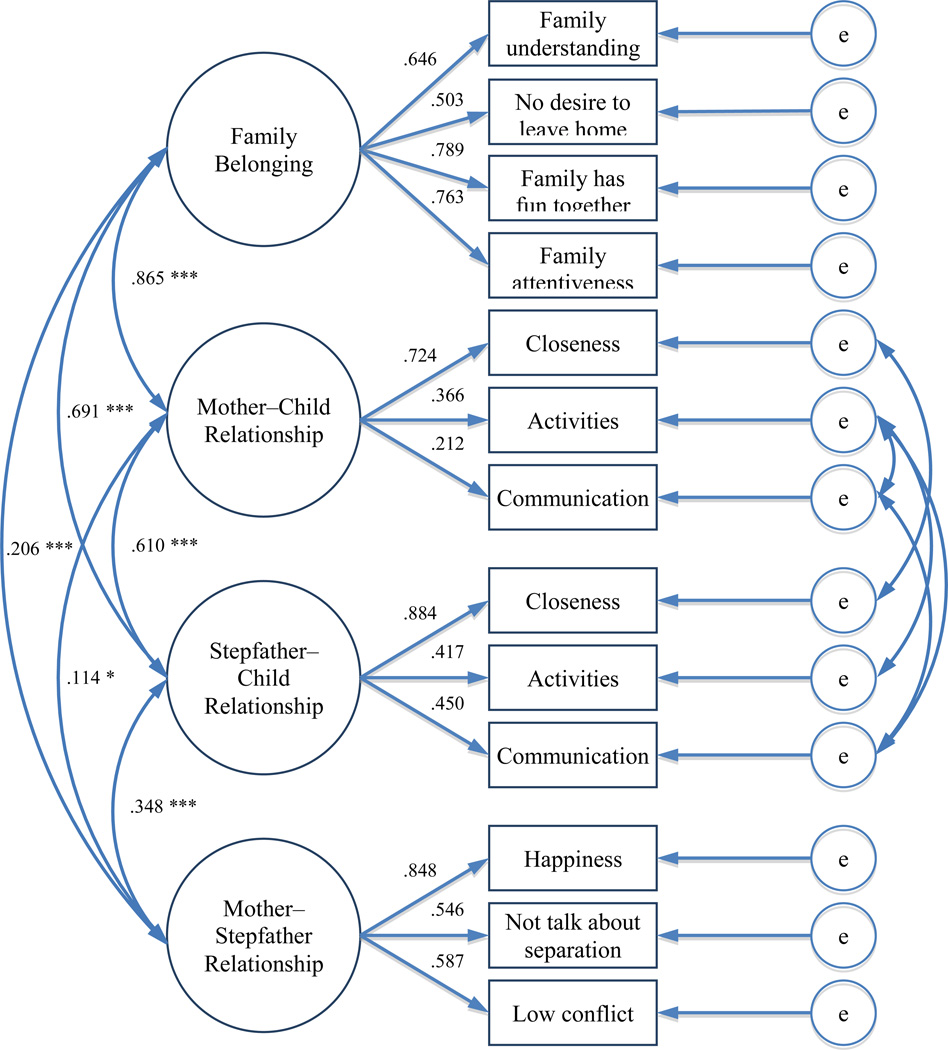

A confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the measurement model provided a good fit for the latent relationship variables, as presented in Figure 2. Examination of modification indices revealed that the fit of the final measurement model could be improved by including correlations between the residuals of several observed variables. The resulting chi-square (148.47, df = 54), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA, .03), and comparative fit index (CFI, .97) for the measurement model indicate good fit. In addition, standardized loadings for the observed indicators of the relationship and belonging variables and correlations between latent variables were generally high. The mother–child and stepfather–child relationships in particular were highly correlated with family belonging, as well as with each other, suggesting that the two may independently affect the adolescent’s feeling of family belonging. Sensitivity analyses (not shown) comparing our final measurement model (see Figure 2) to other models in which family relationship variables were combined with family belonging to create a single latent variable supported our approach to modeling these variables as distinct constructs. Each index of model fit we examined—including the Bayesian Information Criterion, RMSEA, and CFI—clearly indicated better fit for the models in which dyadic relationships and family belonging were treated as separate measures. The Bayesian Information Criterion and RMSEA rose substantially, and the CFI dropped markedly—signs of worsened fit—when the relationship and belonging variables were modeled as one variable. We concluded that our model was preferable to alternative, single-latent-variable models and that modeling parent–child relationships and belonging as a single latent construct was empirically untenable.

Figure 2.

Measurement Model.

Note. Correlations between residuals are as follows: mother closeness with stepfather (SF) closeness = .199, p < .05; mother activities with SF activities = .561, p < .001; mother activities with SF communication = .118, p < .001; mother activities with mother communication = .160, p < .001; mother communication with SF communication = .577, p < .001. χ2(54) = 148.47, p < .001; root-mean-square error of approximation = .03, comparative fit index = .97. All coefficients are fully standardized. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Structural Model

Consistent with the conceptual model (see Figure 1), the structural model posited that dyadic within-family relationships—namely, the mother–child, stepfather–child, and mother–stepfather relationships—directly influence the extent to which adolescents feel they belong to their stepfamilies. Additional background variables were also hypothesized to have direct effects on family belonging, as well as indirect effects through other family relationships. According to well-accepted fit indices, the model as proposed fit the data adequately: RMSEA = .03, CFI = .91.

Standardized regression coefficients for the structural model (see Table 1) indicated that two of the three family relationships in the model significantly predicted adolescents’ perceptions of family belonging when selected characteristics of the child and family were controlled for. The mother–child relationship was most strongly related to family belonging, with a coefficient of 0.774 (p < .001). The stepfather–child relationship was also a significant predictor of family belonging, but this association was smaller in magnitude (b = 0.230, p < .01). The quality of the mother–stepfather relationship appeared to have no association with adolescents’ feelings of family belonging.

Table 1.

Structural Model Predicting Family Belonging in Stepfamilies (N=2,085)

| Predictor | Family belonging | Mother–child relationship |

Stepfather– child relationship |

Mother– stepfather relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family relationships | ||||

| Mother–child relationship | 0.774*** | |||

| Stepfather–child relationship | 0.230** | |||

| Mother–stepfather relationship | 0.018 | |||

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Female | −0.003 | −0.084 | −0.066 | 0.003 |

| Age | 0.016 | −0.200*** | −0.177*** | 0.029 |

| Racea | ||||

| Black | −0.032 | 0.041 | 0.019 | −0.092* |

| Hispanic | 0.070* | −0.030 | −0.054 | 0.023 |

| Other race | −0.064* | 0.065 | −0.008 | −0.059 |

| Immigrant statusb | ||||

| Only adolescent born in United States | −0.029 | 0.022 | −0.060 | −0.067 |

| Adolescent not born in United States | 0.056 | −0.012 | 0.030 | 0.018 |

| Religiosity | −0.016 | 0.122** | 0.135*** | 0.043 |

| Family characteristics | ||||

| Income (log of) | −0.067** | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Mother’s education | −0.025 | 0.068 | −0.030 | −0.098** |

| Years in stepfamily | 0.001 | −0.010 | 0.039 | −0.174*** |

| Number of full siblings | −0.007 | 0.021 | 0.093** | 0.007 |

| Number of stepsiblings | −0.042 | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.017 |

| Number of half-siblings | −0.039 | −0.017 | −0.013 | 0.018 |

Note. Coefficients for the family relationship variables are fully standardized. Coefficients for all other variables are standardized on the dependent variable only. For all four latent variables, a high score indicates a positive relationship. χ2(180) = 579.08, p < .001; root-mean-square error of approximation = .03, comparative fit index = .91.

Reference group for race is White.

Reference group for immigrant status is Both born in the United States.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

With respect to other covariates, only two background variables had direct, and rather modest, effects on family belonging. Adolescents from stepfamilies with higher incomes reported lower belonging, on average (b = −0.067, p < .01), than adolescents from stepfamilies with lower incomes, and adolescents who identified as Hispanic reported stronger feelings of belonging relative to White adolescents (b = 0.07, p < .05). Additional analyses revealed that perceived family belonging among Hispanic adolescents was also significantly higher than among Black adolescents (b = 0.11, p < .05).

Several additional variables were associated with levels of family belonging indirectly, via either the mother–child or the stepfather–child relationship. Indirect effects were calculated using the Sobel (1982) test for mediation of significant pathways (results not shown; all indirect effects were calculated using fully or partially standardized coefficients, consistent with Table 1). This analysis revealed an indirect effect of respondent’s age on family belonging (indirect effect = −0.16, p < .001) by way of the mother–child relationship, reflecting the fact that older adolescents tend to have less close relationships with parents, which in turn contribute to lower levels of family belonging. We also found a significant indirect effect of religiosity on family belonging through the mother–child relationship (indirect effect = 0.09, p < .01) due to the fact that more religious adolescents report closer relationships with mothers.

Three additional covariates had indirect effects on family belonging through the stepfather–child relationship. Here again the analysis revealed a negative indirect effect of age (−0.04, p < .05), indicative of older adolescents’ less close relationships with parents. The indirect effects of religiosity (indirect effect = 0.03, p < .05) and number of full siblings in the household (indirect effect = 0.02, p < .05) were also significant. Adolescents who reported being more religious and having more full siblings also reported closer relationships with stepfathers, which contributed to a greater sense of family belonging.

We used a multigroup model to test for the possibility that gender moderates the associations between the independent variables and family belonging (results not shown). No evidence of moderation by gender was found. The factors that are associated with feelings of family belonging appear to be the same for boys and girls.

Discussion

The results from the present study point to a number of factors that are associated with perceptions of family belonging among adolescents in stepfather families. Consistent with our conceptual model, both the perceived quality of the relationship between adolescents and their mothers, and between adolescents and their stepfathers, were significantly associated with adolescents’ feelings of family belonging. The finding that the mother–child relationship was particularly influential is consistent with Leake’s (2007) findings and with the notion that mothers play a pivotal role in successful stepfamily functioning (Smith, 2008). Still, our findings suggest that stepfathers can also play an independent and important role in fostering feelings of family belonging.

Contrary to expectations, the quality of the mother–stepfather relationship was not associated with adolescent perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies. It appears that the quality of the relationship adolescents have with each of their parents is a more important factor influencing perceptions of family belonging than is the tenor of the mother–stepfather relationship. Of course, it should be kept in mind that some of the most conflicted and unhappy marriages are selected out of stepfamily samples over time through divorce, which may lead to an underestimation of the association between marital quality and feelings of family belonging.

Few other family or child characteristics were directly associated with family belonging, and the effect sizes were much more modest. The results did reveal that Hispanic adolescents reported significantly higher levels of family belonging than White and Black adolescents, despite the fact that they were not significantly more likely to report having more positive ties to mothers or stepfathers. Furthermore, immigrant status was not associated with family belonging; neither did it explain the difference between Hispanics and Whites or Blacks. The lack of racial/ethnic differences in the mother–child and stepfather–child relationship is consistent with a recent study that used Add Health and similar parent–child relationship measures (King et al., 2014), as well as other studies that suggest that there are more similarities between White and Hispanic stepfamily relationships than there are differences (Coltrane, Gutierrez, & Parke, 2008). The higher level of perceived family belonging reported by Hispanic adolescents may be related to familism and stronger beliefs about family obligations—regardless of relationship quality between individuals—noted by Coleman et al. (2006). These scholars suggested that the obligation to help family members extends to stepparents as well as parents and that marriage to a parent is sufficient to make the stepparent part of the kin network, regardless of generational status. They argued that White, African American, and Asian American stepparents do not obtain kin status as easily as do Latino stepparents. Further research is needed to shed light on the family processes underlying Hispanic adolescents’ higher levels of perceived family belonging.

Despite the potential for economic resources to reduce family stress, it was adolescents in lower income families who reported higher levels of family belonging. Perhaps this finding reflects the greater centrality of kin in lower income families (King & Elder, 1998; Lareau, 2003), but further research is needed to shed light on this issue.

Three additional characteristics were significantly, but only indirectly, associated with perceptions of family belonging via the mother–child and/or stepfather–child relationship: (a) number of full siblings, (b) adolescent age, and (c) religiosity. Despite the fact that many religions frown on divorce, this latter finding suggests that the protective effect of religiosity reported to sometimes benefit adolescents living with both biological parents (Holden & Williamson, 2014) can extend to adolescents in stepfamilies. As Cherlin (2009) noted, American religion has been transformed over the past several decades such that most religious groups have modified the way they respond to divorce, reaching out to help people recover from one, despite having formal positions against it.

Overall, our results are very consistent with a family systems perspective and provide evidence that family belonging is a construct that is distinct from dyadic family relationships. Relationships within the family are the most important predictors of adolescent perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies. Among within-family relationships, the mother–child relationship is key, suggesting that family belonging largely, albeit not exclusively, reflects the quality of this relationship. Less clear is how much the primacy of the mother–child relationship derives from the fact that this relationship is with the mother, a biological parent, or the primary caretaker or attachment figure. To gain leverage on this issue, future research should explore family belonging across the full diversity of family forms, such as two-biological-parent families, stepmother families, cohabiting stepfamilies, and gay and lesbian stepfamilies. Whether, and how, the predictors of family belonging are similar or different across family types remains to be seen. Although our study of married stepfather families examined a prevalent stepfamily form, it, and the Add Health data (collected in the mid-1990s), are limited by not being able to address the increasing diversity in stepfamily living.

Although this study identified a number of important factors associated with feelings of family belonging in stepfamilies, data limitations precluded an examination of other potentially important factors that should be examined in future research. For example, a better understanding of the influence of siblings requires more attention to the nature and quality of these relationships as well, but these data are unfortunately not available in Add Health. Future research would also benefit from examining how feelings of family belonging in stepfamilies change over time, ideally from the beginning of stepfamily formation.

Our use of structural equation methods with latent variables allowed us to create comprehensive measures of family relationships. For example, the measures of positive mother–child relationships and stepfather–stepchild relationships were based on multiple indicators, including adolescent perceptions of closeness, sharing a variety of activities with each parent, and engaging in multiple topics of communication, all of which contribute to building positive relationships in stepfamilies (Coleman, Ganong, & Russell, 2013). Many prior studies have relied on more limited measures, especially of the stepfather–stepchild relationship, including studies using Add Health that have employed a single question regarding perceived closeness to the stepfather (King, 2006, 2009). At the same time, however, it must be acknowledged that these measures also have limitations. The activity and communication items, for example, asked only about whether certain events occurred in the past 4 weeks without indicating the frequency of their occurrence or the full range of all possible events. Thus, these indicators are only a proxy of engagement with each parent in activities and communication and may underestimate the true extent of it, particularly when parents are engaging in few activities but at frequent rates.

Another limitation of the current study is the inability to determine whom adolescents were including in their definition of family when answering the questions about family belonging. How often are stepfathers included, and what difference does this make? Are nonresident fathers or others who live outside the mother’s household included? We found no evidence that the quality of the nonresident father–child relationship was associated with adolescent perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies, but whether this may be due to not including the nonresident father as a family member, or whether relationships outside the mother’s household simply exert less influence, is unclear. Whom adolescents include in their definition of family, or which relationships may influence feelings of family belonging in stepfamilies, may also be changing over time, in tandem with other family changes such as increases in joint custody, nonresident father involvement, family instability, and multipartner fertility. Perceptions of family belonging likely also differ depending on who is being asked about it (e.g., child, mother, stepfather, step-sibling).

Prior research suggests that feelings of family belonging protect adolescents from a wide range of negative outcomes, yet we know little regarding what factors influence these perceptions of family belonging. With a significant number of children growing up in stepfamilies it is important to better understand what factors aid in their adjustment and contribute to feelings of belonging within stepfamilies. The current study addressed this gap in the literature by using nationally representative data to examine the associations between an array of family characteristics and adolescent’s perceptions of family belonging in stepfamilies. The results suggest that both stepfathers and, perhaps especially, mothers can play an important role in helping children feel they belong.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to Valarie King, principal investigator (SES-1153189), and by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (R24 HD41025) and Family Demography Training (T-32HD007514). This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by Grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from Grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

References

- Amato PR. More than money? Men’s contributions to their children’s lives. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Men in families: When do they get involved? What differences does it make? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:650–666. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Kane JB. Parents’ marital distress, divorce, and remarriage: Links with daughters’ early family formation transitions. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32:1073–1103. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11404363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS. Family structure and home-leaving: A further specification of the relationship. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:999–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becvar DS, Becvar RJ. Systems theory and family therapy: A primer. Lanham, MD: University Press of America; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick CB. Understanding family process: Basics of family systems theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Manning WD. Family boundary ambiguity and the measurement of family structure: The significance of cohabitation. Demography. 2009;46:85–101. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Raley RK, Sweet JA. The changing character of stepfamilies: Implications of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing. Demography. 1995;32:425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE. Family structure history and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:944–980. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. Remarriage as an incomplete institution. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:634–650. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round. New York: Knopf; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chilman CS. Hispanic families in the United States: Research perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, Fine M. Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1288–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong LH, Rothrauff TC. Racial and ethnic similarities and differences in beliefs about intergenerational assistance to older adults after divorce and remarriage. Family Relations. 2006;55:576–587. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, Russell LT. Resilience in stepfamilies. In: Becvar DS, editor. Handbook of family resilience. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 85–103. doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3917-2_6. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Gutierrez E, Parke RD. Stepfathers in cultural context: Mexican American families in the United States. In: Pryor J, editor. The international handbook of stepfamilies: Policy and practice in legal, research, and clinical environments. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 100–124. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Elder GH. Family dynamics, supportive relationships, and educational resilience during adolescence. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:571–602. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The effects of family cohesiveness and peer encouragement on the development of adolescent alcohol use: A cohort-sequential approach to the analysis of longitudinal data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1994;55:588–599. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine MA, Coleman M, Ganong LH. Consistency in perceptions of the step-parent role among step-parents, parents and stepchildren. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:810–828. [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH, Coleman M, Jamison T. Patterns of stepchild–stepparent relationship development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:396–413. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. Strengthening the links between educational psychology and the study of social contexts. Educational Psychologist. 1992;27:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Greif GL. Out of touch: When parents and children lose contact after divorce. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. 2009 Retrieved from www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children’s adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53:167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3) Serial No. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Kelly J. For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: W. W. Norton; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Stanley-Hagan M. Diversity among stepfamilies. In: Demo DH, Allen KR, Fine MA, editors. Handbook of family diversity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Hansen DA. The identification of conceptual frameworks utilized in family study. Marriage and Family Living. 1960;22:299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Williamson PA. Religion and child well-being. In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frones I, Korbin JE, editors. Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 1137–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, Shafer K. Stepfamily functioning and closeness: Children’s views on second marriages and stepfather relationships. Social Work. 2013;58:127–136. doi: 10.1093/sw/swt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V. The antecedents and consequences of adolescents’ relationships with stepfathers and nonresident fathers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:910–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V. When children have two mothers: Relationships with nonresident mothers, stepmothers, and fathers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1178–1193. [Google Scholar]

- King V. Stepfamily formation: Implications for adolescent ties to mothers, nonresident fathers, and stepfathers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:954–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V. The influence of religion on ties between the generations. In: Ellison CG, Hummer RA, editors. Religion, families, and health: Population-based research in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2010. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- King V, Elder GH. Education and grandparenting roles. Research on Aging. 1998;20:450–474. [Google Scholar]

- King V, Thorsen ML, Amato PR. Factors associated with positive relationships between stepfathers and adolescent stepchildren. Social Science Research. 2014;47:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, Ellis R. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. Living arrangements of children: 2009; pp. 70–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Unequal childhoods. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leake VS. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. 2005. Steps between, steps within: Adolescents and stepfamily belonging. Publication No. 3231196. [Google Scholar]

- Leake VS. Personal, familial, and systemic factors associated with family belonging for stepfamily adolescents. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2007;47:135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W. Stepfathers with minor children living at home: Parenting perceptions and relationship quality. Journal of Family Issues. 1992;13:195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row; 1970. (Original work published 1954) [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Sprenkle DH, Russell CS. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Family Process. 1979;18:3–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1979.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor J. Stepfamilies: A global perspective on research, policy, and practice. New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor J, Rodgers B. Children in changing families: Life after parental separation. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. Resident mothers in stepfamilies. In: Pryor J, editor. The international handbook of stepfamilies: Policy and practice in legal, research, and clinical environments. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SD. How the birth of a child affects involvement with stepchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SD. Brave new stepfamilies: Diverse paths toward stepfamily living. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM. Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman J, Tedrow L. The demography of stepfamilies in the United States. In: Pryor J, editor. The international handbook of stepfamilies: Policy and practice in legal, research, and clinical environments. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen ML, King V. “My mother’s husband”: Factors associated with how adolescents label their stepfathers; Paper presented at the meeting of the Population Association of American; Boston, MA. 2014. May, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM. Parent–child relations and children’s psychological well-being: Do dads matter? Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:55–78. [Google Scholar]