Summary

Background

quadriceps tendon (QT) ruptures are significant injuries that are relatively uncommon. The diagnosis of QT ruptures is frequently missed or delayed. An association between the presence of a patella spur and QT ruptures has been suggested in the literature.

Patients and methods

the Hospital Inpatient Enquiry system was used to gather data on all patients who sustained a QT rupture over a six year period from 2008 to 2014. A retrospective review of the medical notes as well as radiographs was undertaken. We reviewed 200 knee radiographs of patients without QT ruptures to establish the incidence of patella spurs in our normal population. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 11.5 for Windows®.

Results

the records of 20 consecutive patients with 21 QT ruptures were reviewed. The mean age was 60.9 yrs (range 44.9–82.1 yrs) and the majority were male (n=17; 85%). There was one bilateral QT ruptures. Patella spurs were noted in 13 cases (62%) which were significantly higher than in patients without QT rupture 19% (P≤0.05).

Conclusion

we noted a significantly higher incidence of patella spurs in patients with QT ruptures compared to those without. The presence of a QT rupture should be ruled out in patients with a knee injury and a patella spur on the knee radiographs.

Keywords: quadriceps tendon, ruptures, patella spur, knee, injury

Introduction

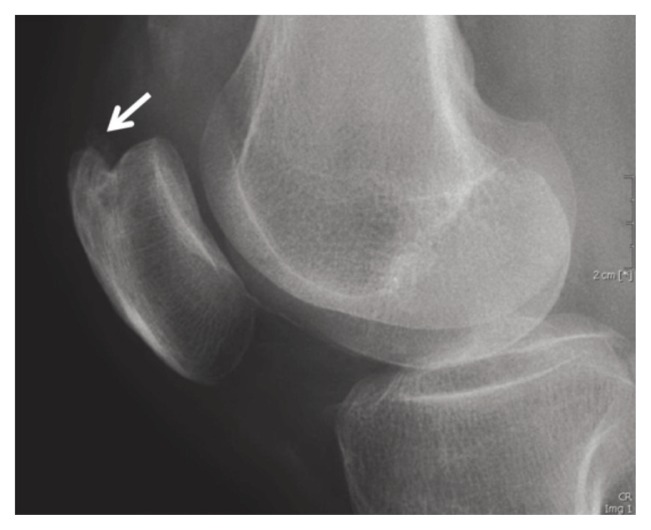

Quadriceps tendon (QT) ruptures are uncommon injuries that predominantly affect middle-aged men1. Ruptures most commonly occur from a powerful, eccentric contraction of the quadriceps muscle, when the knee is partially flexed and the foot is planted on the floor. This injury is most frequently caused by falls, however other mechanisms include direct trauma, lacerations and iatrogenic causes2. Degenerative changes associated with ageing and calcific tendinopathy have also been shown to be a factor with QT ruptures3,4. Spontaneous QT ruptures have been shown to be associated with predisposing conditions such as diabetes, chronic renal failure5, gout6, and quinolone antibiotic use7 amongst others. It has also been suggested that the presence of a patella spur, a bony prominence at the QT tendon insertion point of the proximal pole may be associated with ruptures (Fig. 1)8. We examined a series of QT ruptures to see if such an association existed among our patients.

Figure 1.

Lateral radiograph of a knee demonstrating a proximal patellar pole spur (white arrow).

Patients and methods

All patients with a QT rupture who had undergone repair over a six year period (from July 2008 to July 2014) were reviewed. Data were collected retrospectively using the Hospital In-Patient Enquiry (HIPE) system and patient’s medical notes. The study meets the ethical standards of the Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal9. Details include patient demographics, surgical details, mechanism and side of injury and knee radiographs. Twenty-four patients were identified. We excluded one patient who had under-gone exploration of an open muscolotendinous tear from a penetrating injury and two patients with patella tendon ruptures who had been miscoded. The patient’s radiographs were reviewed to confirm the presence or absence of a patella spur. The Insall-Salvati index of <0.8 was used on preoperative radiographs when no other radiographic features of a QT rupture were present. The lateral radiographs of 200 consecutive non-injured knees were collected from the emergency department and examined to ascertain the incidence of patella spurs in the population without QT ruptures. Statistical analysis was performed with the Chi-Squared test using SPSS version 11.5 for Windows®, with a P value ≤0.05 considered significant.

Results

Of the 20 patients identified, 19 had unilateral ruptures while one patient had asynchronous ruptures to both QT’s approximately one year apart. The QT ruptures were predominantly in males (85%) with a mean age of 68.6 years. Indirect trauma was the most frequent mechanism of injury in our series (Tab. 1). A lateral radiograph was included for review in all patients in the series (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics comparing the patient’s with QT-ruptures to those without.

| Non-QT rupture | QT rupture | |

|---|---|---|

| Total = n | 200 | 21 |

| Age = years (range) | 67.1 (45.1–80.7) | 68.9 (44.9–82.1) |

| Gender = n (%) | Male = 166 (83%) | Male = 17 (85%) Female = 3 (15%) |

| Side = n (%) | Left = 95 (47.5%) Right = 105 (52.5%) |

Left = 12 (57%) Right = 9 (43%) |

| Mechanism = n (%) | N/A | Direct = 4 (19%) Indirect = 16 (76%) Unknown = 1 (5%) |

| Spur Present = n (%) | Yes = 38 (19%) No = 162 (81%) |

Yes = 13 (62%) No = 8 (38%) |

The majority of QT ruptures (90.5%) were identified clinically with having a loss of the normal extensor mechanism of the knee and a palpable suprapatellar gap. The remaining two patients had large haemarthroses making clinical examination equivocal: the diagnosis was in these cases confirmed by ultrasonography. One patient had rupture both QT’s about 1 year apart. While six patients had mild renal impairment at the time of admission none had a history of chronic renal failure, gout, steroid or quinolone use. Analysis of the 200 lateral radiographs of normal, non-QT ruptured knees had an incidental finding of 38 (19%) patellar spurs. The patient characteristics of both cohorts were similar for age and gender and shown in Table 1. Statistical analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between the presence of patella tendon spurs and QT ruptures (P ≤0.05).

Discussion

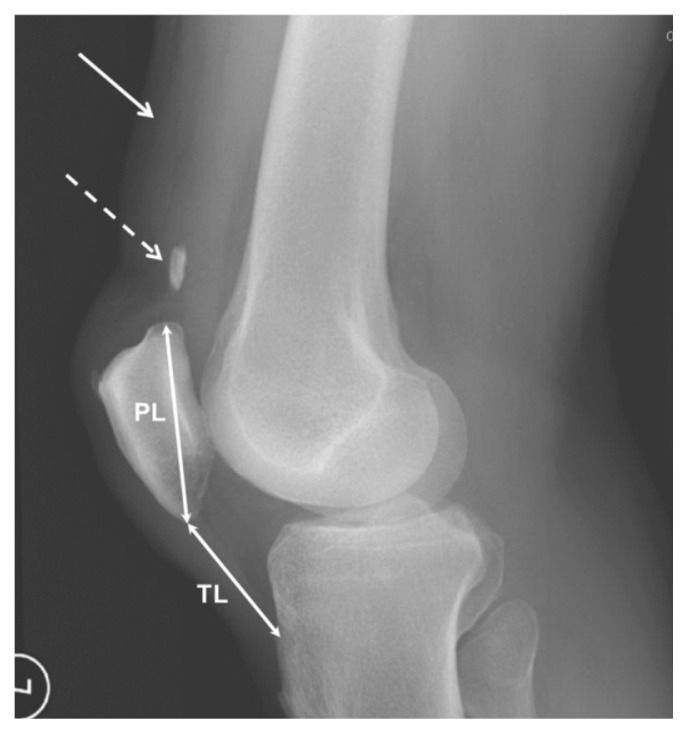

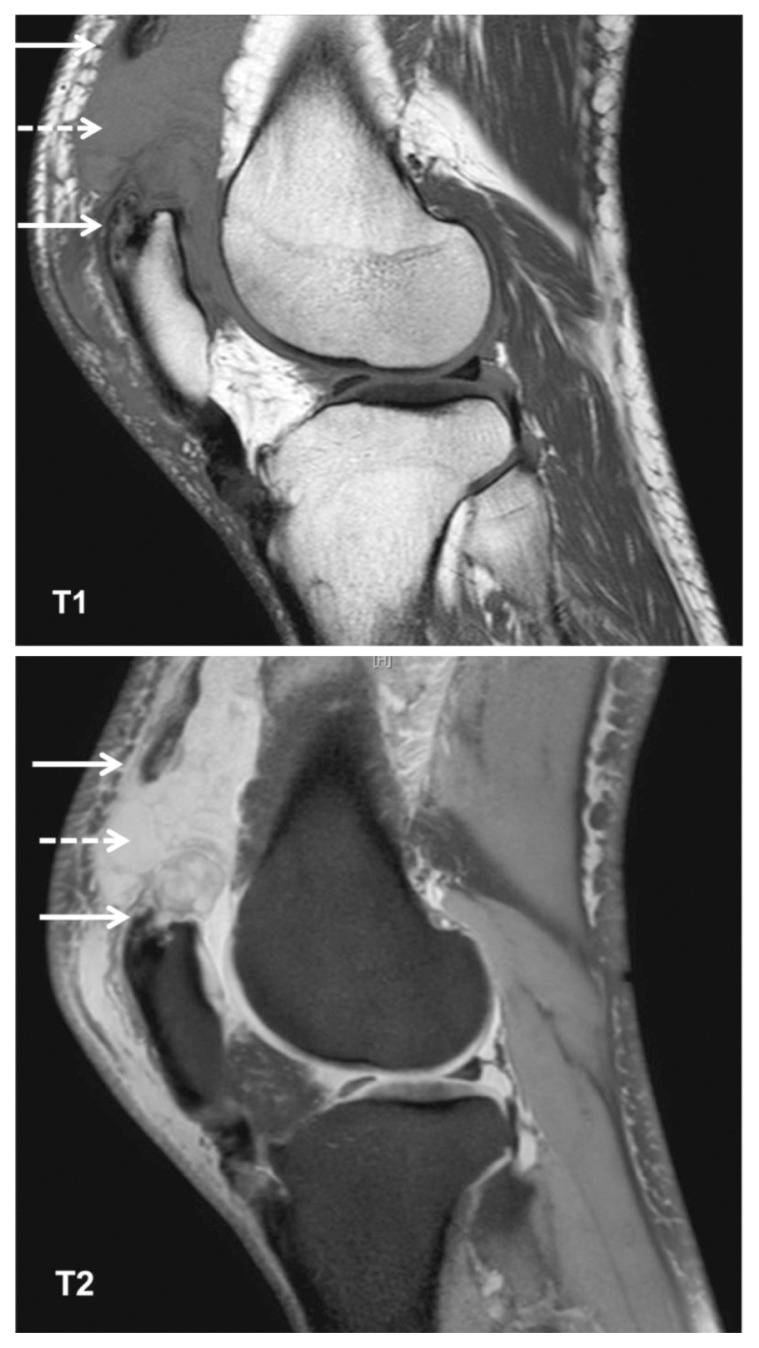

QT ruptures are infrequent injuries and relatively rare when all types of knee injuries are factored1. They most often occur in men over 40 years of age and are more common than patellar tendon ruptures10. Unilateral ruptures are more common than bilateral. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical repair have been shown to have good outcomes in QT ruptures, aided in part by the technical simplicity of the operation11,12. Patellar tendinopathy and ruptures have been studied in more detail and it is believed that eccentric exercises and even surgical interventions may be beneficial in tendinopathies which may avoid their progression and subsequent tendon ruptures13–15. Clinical features of QT ruptures include the triad of pain, loss of extension and a suprapatellar gap. However, clinical examination may be limited by both pain and swelling leading to a high rate of misdiagnosis, estimated between 10–50%16,17. Radiographic features include the obliteration of the quadriceps shadow, a visible suprapatellar soft tissue mass (due to the retracted tendon), an osseous avulsion fragment (from the proximal pole) and patella baja (low riding patella)18. The Insall-Salvati index which is a ratio of the patella tendon length to the patella length on the lateral radiograph is useful in detecting a low riding patella or patella baja when the index is <0.8 (Fig. 2)19. Ultrasonography (US) has proven to be a better modality than radiographs for the diagnosis of QT ruptures and can further differentiate between partial and complete tears as well as the tear location10,20. Magnetic resonance has greater sensitivity and specificity than US, however it is more expensive, time consuming and limited by its availability (Fig. 3)21.

Figure 2.

Lateral radiograph of a knee with a quadriceps tendon rupture demonstrating a low lying patella (patella baja), suprapatella calcific density (dashed arrow) and obliteration of the quadriceps tendon shadow and haematoma (solid arrow).

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging (T1 and T2 weighted sagittal views) of the knee illustrating a ruptured QT (solid arrows) and a large haematoma (dashed arrow).

Bony spurs are most commonly caused by osteoarthritis, with a higher incidence found in the elderly population. The presence of a patellar spur has been associated with anterior knee pain22. Studies have hypothesized an association between patella spurs found on lateral knee radiographs and QT ruptures8. To date we have found one study that looked at the presence of patella spurs and extensor mechanism ruptures in patients with patella fractures, patella tendon ruptures and QT ruptures8. They noted the presence of patella spurs in 27% of the patella tendon group, and 15% of the patella fracture group. In the QT rupture group 23 of 29 (79%) had a patella spur, however they did not have radiographs available for 7 (19%) patients and therefore were excluded from analysis. They did not examine the incidence of patella spurs within the non-QT rupture population. Our study confirms the high incidence of patella spurs amongst those with QT ruptures (62%), however less than the previously reported 79% incidence of patella spurs. We excluded patients with partial tears who were treated conservatively and discharged.

The study is limited mainly by its retrospective nature and the small sample size of 20 patients with QT ruptures due to the relative infrequency of the injury. Another limitation of the study was that our cohort only included patients who underwent surgical intervention and had complete tears. Patients with partial tears or those who were managed non-operatively were not analyzed. The study accounted for the most common patient risk factors associated with QT ruptures however this was limited to the patient’s medical notes and there may be non-documented risk factors present.

This retrospective study identified a significantly higher incidence of patella spurs amongst patients with QT ruptures compared to those without. Based on our findings, we would recommend in the clinical setting of a knee injury with a patellar spur on the lateral radiograph, the clinician should consider the presence of a QT rupture.

References

- 1.Clayton RA, Court-Brown CM. The epidemiology of musculoskeletal tendinous and ligamentous injuries. Injury. 2008;39:1338–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scuderi C. Rupture of the quadriceps tendon: study of twenty tendon ruptures. American Journal of Surgery. 1958;95:626–635. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(58)90444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidil A, Ouaknine M, Anract P, Tomeno B. Trauma-induced tears of the quadriceps tendon: 47 cases. Rev Chir Orthop. 2004;90:40–48. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(04)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliva F, Giai Via A, Maffulli N. Physiopathology of intratendinous calcific deposition. BMC Med. 2012;10:95. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah MK. Simultaneous bilateral rupture of quadriceps tendons: analysis of risk factors and associations. Southern Medical Journal. 2002;95:860–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy M, Seelenfreund M, Maor P, Fried A, Lurie M. Bilateral spontaneous and simultaneous rupture of the quadriceps tendons in gout. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53(3):510–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalid Y, Zhanel GG. Musculoskeletal injury associated with fluoroquinolones antibiotics. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy JR, Chimutengwende-Gordon M, Bakar I. Rupture of the quadriceps tendon: an association with a patellar spur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1361–1363. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B10.16624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La S, Fessell DP, Femino JE, Jacobson JA, Jamadar D, Hayes C. Sonography of partial-thickness quadriceps tendon tears with surgical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:1323–1329. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.12.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rougraff BT, Reeck CC, Essenmacher J. Complete quadriceps tendon ruptures. Orthopedics. 1996;19:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdano MA, Zanelli M, Aliani D, Corsini T, Pellegrini A, Ceccarelli F. Quadriceps tendon rupture in healthy patients treated with patellar drilling holes: clinical and ultrasonographic analysis after 36 months of follow-up. MLTJ. 2014;4(2):194–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maffulli N, Oliva F, Maffulli G, King JB, Del Buono A. Surgery for unilateral and bilateral patellar tendinopathy: a seven year comparative study. Int Orthop. 2014;38(8):1717–1722. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2390-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frizziero A, Trainito S, Oliva F, Nicoli Aldini N, Masiero S, Maffulli N. The role of eccentric exercise in sport injuries rehabilitation. Br Med Bull. 2014;110(1):47–75. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldu006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaseirlis DA, Konstantinidis GA, Malliaropoulos N, Nakou LS, Korompilias A, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy in high-level athletes. MLTJ. 2013;2(4):267–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilan DI, Tejwani N, Keschner M, Leibman M. Quadriceps tendon rupture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:192–200. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaRocco BG, Zulpko G, Sierzenski P. Ultrasound diagnosis of quadriceps tendon rupture. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko K, DeMouy EH, Brunet ME, Benzian J. Radiographic diagnosis of quadriceps tendon rupture: Analysis of diagnostic failure. J Emerg Med. 1994;12:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)90703-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insall J, Salvati E. Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology. 1971;101:101–104. doi: 10.1148/101.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi S, Zwass A, Abdelwahab IF, Banderali A. Diagnosis of tears of the quadriceps tendon of the knee: Value of sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:1137–1140. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.5.8165998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swamy GN1, Nanjayan SK, Yallappa S, Bishnoi A, Pickering SA. Is ultrasound diagnosis reliable in acute extensor tendon injuries of the knee? Acta Orthop Belg. 2012;78(6):764–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adekoya-Cole TO, Enweluzo GO, Akinmokun OI, Olugbemi OO. Anterior knee pain associated with an anterior superior patellar bony spur: a case report. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2013;23(1):27–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]