Abstract

Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is a newly described tumour suppressor that inhibits oncogenesis by suppressing gene transcription and translation. Loss of PDCD4 expression has been found in several types of human cancers including the most common cancer of the brain, the gliomas. However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for PDCD4 gene silencing in tumour cells remain unclear. Here we report the identification of 5′CpG island methylation as the predominant cause of PDCD4 mRNA silencing in gliomas. The methylation of the PDCD4 5′CpG island was found in 47% (14/30) of glioma tissues, which was significantly associated with the loss of PDCD4 mRNA expression (γ=−1.000, P < 0.0001). Blocking methylation in glioma cells using a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, restored the PDCD4 gene expression, inhibited their proliferation and reduced their colony formation capacity. Longitudinal studies of a cohort of 84 patients with gliomas revealed that poor prognosis of patients with high-grade tumours were significantly associated with loss of PDCD4 expression. Thus, our current study suggests, for the first time, that PDCD4 5′CpG island methylation blocks PDCD4 expression at mRNA levels in gliomas. These results also indicate that PDCD4 reactivation might be an effective new strategy for the treatment of gliomas.

Keywords: PDCD4, tumour suppressor gene, glioma, methylation

Introduction

Human gliomas are the most frequent primary tumours of the central nervous system. Because nearly half of them are malignant, their treatment represents one of the most formidable challenges in clinical medicine. Over the past two decades, the overall survival rate of patients with gliomas has hardly improved, with only ∼2% of patients aged 65 years or older survived for more than 2 years [1, 2]. Therefore, new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies are needed to control this devastating disease.

Recently, considerable progress has been made in understanding the genetic alterations that are associated with gliomas, which involve both oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes [3]. We previously reported that one of the newly described tumour suppressor genes, designated programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), was silenced in the vast majority of human gliomas, 77% at protein level and 47% at mRNA level [4]. PDCD4, or MA3, was first cloned as a gene whose expression was elevated in mouse cell lines undergoing apoptosis [5]. Its homologues of human (H731; TIS), chicken and rat (DUG) were soon described [6–8]. Previous studies have shown that PDCD4 directly interacts with the eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4A complex to inhibit protein translation. It prevents tumour transformation in the mouse JB6 model system through inhibiting activating protein 1 (AP-1) function [9–11]. Consequently, PDCD4-deficient mice develop spontaneous tumours of the lymphoid origin [12], and PDCD4 transgenic mice showed significant resistance to tumour induction [13]. Furthermore, PDCD4 exerted its anti-tumour roles via regulating signal transduction pathways [14, 15].

Human PDCD4 was first cloned from a human glioma library, which is highly homologous to the mouse PDCD4[16]. PDCD4 is expressed ubiquitously in normal tissues, but its loss or reduction was found in several types of human cancer cell lines [17], and some primary tumours such as human gliomas [4], lung cancer [18], hepatocellular carcinomas [19] and pancreatic cancer [20]. Asangani et al. indicate that MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) may post-transcriptionally regulate PDCD4 expression in colorectal cancer [21]. Dorrello et al. find that S6K1 and betaTRCP may control the levels of PDCD4 protein through an ubiquitination-dependent mechanism [22]. However, the mechanisms of PDCD4 silencing at the transcriptional level are unknown.

In recent years, epigenetic studies have revealed that DNA modifications, e.g. 5′CpG island hypermethylation, can cause tumour suppressor gene inactivation and therefore, the development of cancer [23–25]. We therefore reasoned that epigenetic changes of the PDCD4 gene may be involved in the development of human primary gliomas. We report here that PDCD4 gene silencing in gliomas was associated with 5′CpG island methylation and unfavourable prognosis of patients.

Materials and methods

Tumour specimens and cell lines

A total of 84 glioma specimens including 30 frozen [4] and 54 paraffin-embedded tissues were obtained from patients aged between 30 and 60 years (median = 40 years) who underwent operations at the Department of Neurosurgery in Qilu Hospital of Shandong University from October 2003 to March 2006. The pathological diagnoses were carried out according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for gliomas. The patients’ profiles are presented in Table 1. None of the patients studied had received adjuvant immunosuppressive treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to surgery in order to eliminate their effects on gene expression. Three non-tumour brain tissue samples were excised from tumour-adjacent sites. U251 and U87 cell lines derived from gliomas were purchased from Shanghai Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). They were respectively cultured and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% foetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL). This study is in full compliance with the national legislation and the ethical standards of the Chinese Medical Association.

Table 1.

PDCD4 expression in human glioma tissues

| Parameters | PDCD4 – | PDCD4 + | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 68 | 16 | ||

| Gender | Male | 39 | 14 | 0.0245* |

| Female | 29 | 2 | ||

| Age (years) | >40 | 38 | 10 | 0.6303 |

| ≤40 | 30 | 6 | ||

| Histological types | Astrocytoma | 39 | 8 | 0.8557 |

| Glioblastoma | 19 | 5 | ||

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 10 | 3 | ||

| Grade | Low grade (I, II) | 28 | 5 | 0.4645 |

| High grade (III, IV) | 40 | 11 |

P < 0.05.

PDCD4 expression in human glioma tissues. The clinical parameters include gender, age, histological types and grade.

PDCD4 expression: loss, PDCD4−; expression, PDCD4−.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from 30 frozen glioma specimens, 3 frozen non-tumour brain tissue samples and 2 glioma cell lines (U251 and U87) using a modified TRIzol® one-step extraction method (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) [26, 27]. cDNA was synthesized using the Reverse-Transcribe Kit (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed with PDCD4 specific primers (sense 5′-CCAAAGAAAGGTGGTGCA-3′, and anti-sense 5′-TGA GGTACTTCCAGTTCC-3′) for 35 cycles (95°C for 90 sec., 66°C for 90 sec. and 72°C for 90 sec.). Human β-actin was amplified as an internal control. The RT-PCR was performed at least twice for each sample.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot

The proteins were extracted from tissue samples and glioma cell lines using a modified TRIzol® one-step extraction method [26, 27]. The protein extract was dissolved in loading buffer (1 mM Tris Cl, 3% SDS, 60% glycerol, 75 mM DTT), and each sample was analysed by SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel. The nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with rabbit anti-human PDCD4 polyclonal (1:10,000) or rabbit anti-human β-actin polyclonal (1:1000) at 4°C overnight. The antibodies separately were from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA) and Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The concentration of protein was determined by Bradford analysis.

DNA bisulphite modification and bisulphite sequencing

To differentiate methylated CpGs from unmethylated CpGs, 2 μg of purified genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulphite in a CpGenome™ Fast DNA Modification kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) at 50°C for 16–20 hrs according to manufacturer’s instructions. The position of CpG island was predicted and primers for bisulphite genomic sequencing PCR (BSP) were designed by the CpG software provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/emboss/cpgplot/index.html) and by MethPrimer software [28]. PCR was done using the following primers: 5′-TTTTTATTTTTTAGTATTGTTTTTTTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTATTTATTTTTATTTTCTTCTACCCAATA-3′ (anti-sense). PCR mixture contained 12.5 μl of 2× Master Mix (0.1 U Taq DNA polymerase, 500 μM dNTP, 3 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl), 0.5 μl of forward primer (5 μM), 0.5 μl of reverse primer (5 μM), 1 μl of the bisulphite-modified DNA sample and 10.5 μl of H2O. For bisulphite sequencing, PCR products were gel-extracted and cloned into the PMD18-T Vector (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China), and 10 clones for each sample were sequenced using M13F or M13R primer by the Boya Biotechnology Sequencing Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cytosines in CpG dinucleotides that remained unconverted after bisulphite treatment were considered to be methylated.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

The bisulphite modificated genomic DNAs were used as templates for MSP. PCR amplification was done using HotStar DNA polymerase (Takara Biotechnology) under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min. (hot start), 40 cycles of 30 sec. at 95°C, 1 min. at 58°C and 1 min. at 72°C, and 5 min. of final extension at 72°C. DNA from adjacent normal glial tissues was used as negative controls. Five groups of primers for methylation and unmethylation were designed using MethPrimer software. One group of PDCD4 primers which worked best was 5′-TTTAGTTTCGGTTTCGTCGTTAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAAAAATCTCTAACCCTTCTCGC-3′ (anti-sense) for the methylated sequence, and 5′-TTTAGTTTTGGTTTTGTTGTTATGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAAAAAATCTCTAACCCTTCTCACT-3′ (anti-sense) for the unmethylated sequence. The DNA methylation status of the PDCD4 CpG island was determined in glioma samples and cell lines by bisulphite conversion of unmethylated, but not methylated, cytosine to uracil as previously described [29].

5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment

The glioma cell lines, U251 and U87, were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in culture medium and allowed to attach over a 24-hr period. 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was then added to final concentrations of 0, 2, 5, 10 μM and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 hrs. At the end of the treatment, the medium was removed; and the RNA, DNA and protein were extracted for RT-PCR, methylation analysis, and protein analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (5 μm) were stained with anti-PDCD4 antibody (Cat. 3975, ProSci Incorporated, Poway, CA, USA) by incubating overnight at 4°C. Secondary staining with biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and tertiary staining with HRP-conjugated streptoavidin, were performed with an ABC kit and DAB Peroxidase Substrate kit (Maixin Co., Fuzhou, China). The nuclei were counterstained with the haematoxylin. Negative controls for the specificity of immunohistochemical reactions were performed by replacing the primary antibody with phosphate-buffered saline. All slides were independently analysed by two pathologists. Cells were cultured in the Lab-Tek chamber glass slide (Nalgen Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA), fixed by incubating with 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer for 10 min. and then followed by treatment for 1 min. with cold acetone. The fixed cells were stained in the same way as the paraffin sections described above.

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

U251 and U87 cell lines were transfected with pDsRed2-N1 and pDsRed2-N1-PDCD4 for 24–72 hrs. Cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and/or propidium iodide (Jingmei Biotech Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Apoptosis and cell cycle progression were analysed by flow cytometry using the Beckman Coulter Cytomics™ FC 500 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Colony formation assay

U251 (1.25 × 105 cells) cells and U87 (1.1 × 105 cells) were plated in 24-well plates for 24 hrs and transfected with pDsRed2-N1 and pDsRed2-N1-PDCD4 vector using Lipofectin (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 24 hrs, cells were reseeded in six-well plates with a density of 5000 cells per plate in the presence of G418 (400 μg/ml) for 2–3 weeks. The colonies were fixed with 20% methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s coefficient test was used to analyse the correlation between the hypermethylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island and the loss of PDCD4 expression. The ×2 test was used to compare the expression of PDCD4 with clinicopathological parameters. Cumulative survival time was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method and analysed only for 84 gliomas by the log-rank test. Multivariate survival analysis was performed with the Cox regression model for all 84 gliomas. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed with the SPSS statistical software.

Results

Methylation of the PDCD4 5′CpG island is common in glioma cell lines and primary gliomas

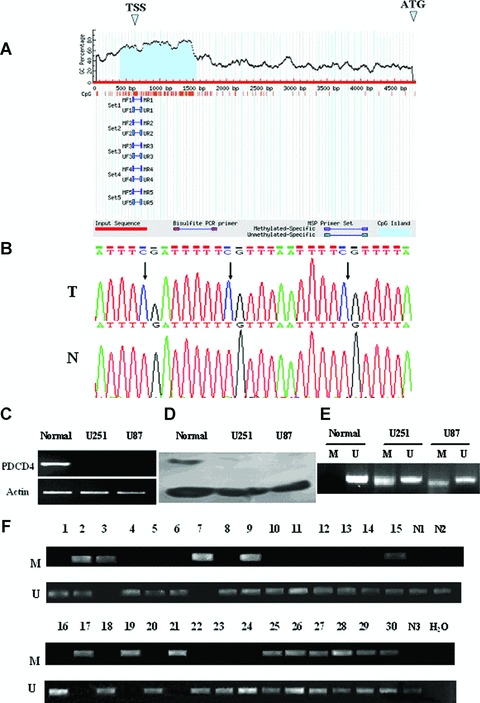

Of the 30 frozen glioma samples examined previously, 47% (14/30) of them lacked the PDCD4 mRNA expression [4]. However, the mechanisms of the PDCD4 silencing at mRNA levels are unclear. 5′CpG island methylation is a common epigenetic mechanism implicated in the silencing of tumour suppressor genes in human cancers [24]. To determine whether 5′CpG island methylation is responsible for PDCD4 silencing in gliomas, we first searched for 5′CpG islands in the PDCD4 gene as described in the section ‘Materials and methods’. A typical CpG island (−251 to +918 bp) was found around the transcription start site of the PDCD4 gene including the first exon and part of the upstream transcription start site sequence (Fig. 1A). This suggests that PDCD4 may be vulnerable to methylation-mediated silencing. To test this theory, genomic DNAs from glioma cell lines and primary gliomas as well non-tumour brain specimens were purified and used as templates for BSP and PCR (MSP) after bisulphite modification. As shown in Fig. 1B–F and Table 2, the methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island was detected in both PDCD4– cell lines (U251 and U87) and 14 specimens of PDCD4 mRNA– primary gliomas whereas no methylation was found in non-tumour brain tissues. Among methylated glioma samples, 5 (nos. 3, 7, 17, 19, 21) showed complete methylation (M: + and U: −) and the rest (nos. 2, 9, 15, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30) as well as two cell lines, showed incomplete methylation (M: + and U: +). Both complete and incomplete methylations of 5′CpG island were able to cause the silencing of PDCD4 at mRNA level.

Fig 1.

Methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island in glioma cell lines, non-tumour brain and glioma tissues. (A) Schematic representation of the CpG island of human PDCD4 gene. (B) Representative figure of methylation. T: tumour tissue; N: non-tumour brain tissue. Arrows, the methylated CpGs. (C)–(F). PDCD4 mRNA (C) and protein (D) expression and PDCD4 gene methylation (E) as determined by RT-PCR, Western blot and methylation-specific PCR, respectively. U251 and U87, two glioma cell lines; normal, non-tumour brain tissue; M, methylated; U, unmethylated. (F) Methylation status of the PDCD4 cytosine island in non-tumour brain and primary glioma tissues. 1–30, primary glioma tissues from 30 patients; N, non-tumour brain tissues; H2O, untransfected control

Table 2.

Expression and methylation status of PDCD4 in cell lines and tissues

| mRNA | Methylation | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lines | U251 | − | + | |

| U87 | − | + | ||

| Non-tumour brain tissues | 1 | ++++ | − | |

| 2 | ++++ | − | ||

| 3 | ++++ | − | ||

| Gliomas | 1 | ++++ | − | IV |

| 2 | − | + | IV | |

| 3 | − | + | IV | |

| 4 | + | − | IV | |

| 5 | + | − | III | |

| 6 | + | − | III | |

| 7 | − | + | III | |

| 8 | +++ | − | III | |

| 9 | − | + | IV | |

| 10 | + | − | III | |

| 11 | ++++ | − | IV | |

| 12 | ++ | − | IV | |

| 13 | + | − | III | |

| 14 | + | − | IV | |

| 15 | − | + | IV | |

| 16 | + | − | IV | |

| 17 | − | + | III | |

| 18 | + | − | II | |

| 19 | − | + | II | |

| 20 | +++ | − | IV | |

| 21 | − | + | IV | |

| 22 | ++ | − | III | |

| 23 | + | − | IV | |

| 24 | + | − | III | |

| 25 | − | + | III | |

| 26 | − | + | III | |

| 27 | − | + | IV | |

| 28 | − | + | III | |

| 29 | − | + | IV | |

| 30 | − | + | III |

Expression and methylation status of PDCD4 in cell lines and tissues. The pathological grades were assigned according to the new 2007 WHO criteria for gliomas. The PDCD4 mRNA levels were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, and normalized against the levels of β-actin in the same sample: −, not detectable; +, 0.01 to 0.49; ++, 0.5 to 0.99; +++, 1.0 to 1.99; ++++, ≥2.00. Methylation was detected by methylation-specific PCR: +, methylated; −, unmethylated.

5′CpG island methylation is associated with loss of PDCD4 expression at mRNA level in the glioma cell lines and primary glioma tissues

We next examined the relationship between PDCD4 5′CpG island methylation and PDCD4 gene silencing at mRNA level. Normal brain tissues and several PDCD4-expressing gliomas showed no methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island. In contrast, glioma cell lines and all of the PDCD4– glioma tissues showed clear PDCD4 5′CpG island methylation (Table 2). The correlation between 5′CpG island methylation and PDCD4 gene silencing at mRNA level was statistically significant (Pearson’s correlation coefficient is −1.000, P < 0.0001). These results indicated that CpG island methylation is significantly associated with the loss of PDCD4 expression at mRNA levels.

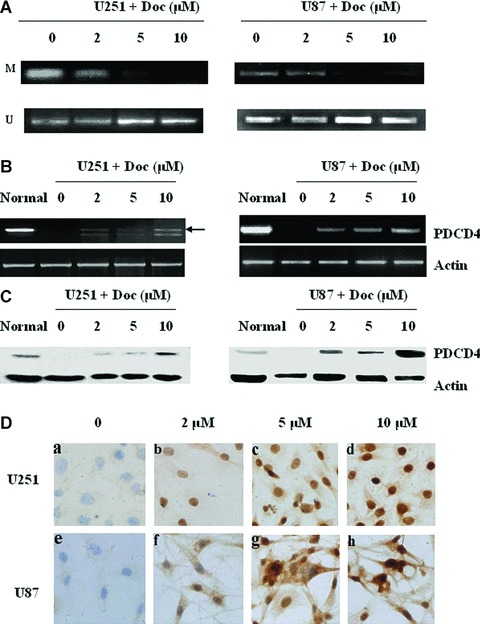

Blocking methylation in glioma cells effectively restores PDCD4 expression

To determine whether CpG island methylation of the PDCD4 5′CpG island causes the loss of PDCD4 expression, glioma cell lines which had the PDCD4 5′CpG island methylation (U251 and U87) were exposed to increasing concentrations of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. After 48 hrs treatment, the methyltransferase inhibitor had no effect on the viability of the glioma cells (data not shown) but significantly decreased the methylation (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the status of demethylation, the PCR products were also sequenced after the treatment of high concentration 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. The methylated sites disappeared in both glioma cell lines (data not shown). Remarkably, blocking methylation resulted in a substantial restoration of PDCD4 expression at both mRNA (Fig. 2B) and protein levels (Fig. 2C and D). Of note is that although two bands appeared in the PDCD4 PCR products of treated U251 cell line, only the upper band was PDCD4 specific as confirmed by sequencing. These results indicated that PDCD4 silencing at mRNA level in glioma cells was predominantly caused by 5′CpG island methylation.

Fig 2.

Demethylation of PDCD4 gene restored the PDCD4 expression in glioma cells. Glioma cells (U251 and U87) were cultured with 0, 2, 5, or 10 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Doc) for 48 hrs. De-methylation status of the PDCD4 CpG island was detected by methylation-specific PCR; M, methylated; U, unmethylated (A). The expression of PDCD4 at 48 hrs was examined by RT-PCR (B), Western blot (C) and immunocytochemistry (D). Normal brain tissue (normal) not treated with Doc was used as a control.

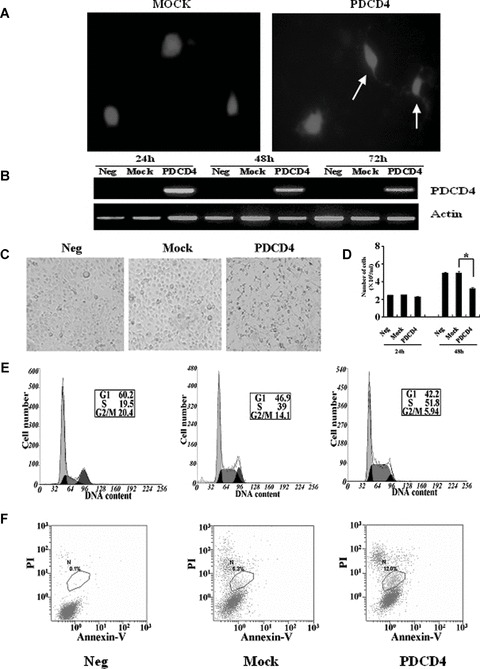

Restoration of PDCD4 expression in glioma cells inhibited their proliferation, induced their apoptosis and prevented their colony formation

The frequent loss of PDCD4 expression in glioma cells suggests that PDCD4 may inhibit the proliferation of gliomas. To determine the effect of PDCD4 on the growth and survival of glioma cells, a recombinant pDsRed plasmid carrying the full-length PDCD4 cDNA was transfected into PDCD4– U251 and U87 glioma cells. Forty-eight hours later, both the fluorescent marker and PDCD4 were detected in the glioma cells (Fig. 3A and B). Importantly, PDCD4 expression in these cells significantly inhibited their growth, compared with untransfected control and mock-transfected groups (Fig. 3C and D). Cell cycle analysis further revealed that PDCD4 expression significantly increased the number of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycles (38.47%± 1.39 in mock versus 50.83%± 2.27 in the PDCD4 group) (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, annexin V-FITC/PI analysis clearly showed that PDCD4-transfected glioma cells underwent more apoptosis than the controls (4.96%± 1.04 in mock versus 11.62%± 0.95 in the PDCD4 group) (Fig. 3F).

Fig 3.

Re-constitution of PDCD4– glioma cells with PDCD4 inhibited their growth and induced their apoptosis. (A) After transient transfection with PDCD4 for 48 hrs, the U251 cells were examined by fluorescent microscopy. Transfected cells express the red fluorescent protein, DsRed2, which are shown in red. (B) PDCD4 expression in U251 glioma cells was examined by RT-PCR after transient transfection (24, 48 and 72 hrs) with PDCD4 plasmids (PDCD4), or empty vector (Mock). Untransfected PDCD4– glioma cells were used as a control. (C) The morphology of U251 cells with or without PDCD4 expression. (D) Total number of U251 cells per millilitre of culture medium 24 and 48 hrs after the transfection. *, P < 0.05. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Cell cycle analysis. (F) Apoptosis analysis. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

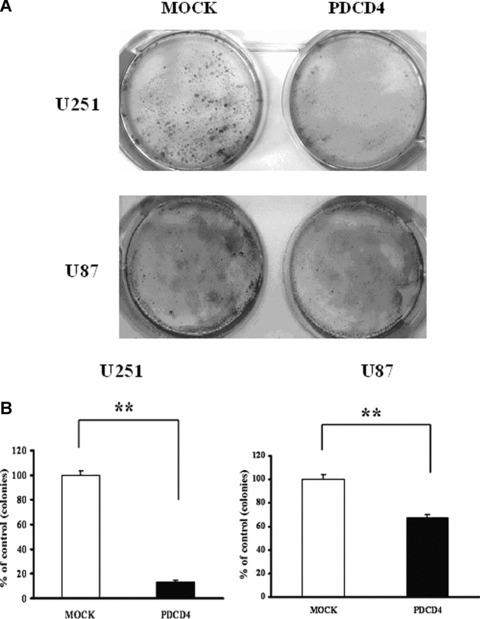

Glioma cells, unlike normal glia cells, have the tendency to form colonies in the culture (Fig. 4). Remarkably, PDCD4-transfection significantly diminished the capacity of these cells to form colonies. Specifically, compared with the mock control, the expression of PDCD4 caused 86.47%± 1.10 and 32.68%± 0.34 reductions in the number of colonies formed by U251 cells and U87 cells, respectively (P < 0.01). Thus, PDCD4 expression reduces the growth and colony forming capacity of glioma cells.

Fig 4.

Re-constitution of PDCD4– glioma cells with PDCD4 reduced their colony-forming capacity. The U251 and U87 glioma cells were transfected with PDCD4 plasmids or empty vector (Mock) and selected with G418 for 2–3 weeks. The number of colonies formed on the plates was counted. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01.

PDCD4 expression in human primary glioma tissues improved the prognosis of patients with high-grade gliomas

The above results showed that restoration of PDCD4 expression inhibited proliferation and prevented colony formation of cell lines in vitro. To determine whether PDCD4 expression in primary gliomas also affects tumorigenesis, we examined firstly the PDCD4 expression in paraffin-embedded glioma tissues of an additional 54 patients by immunohistochemistry [4]. We found that the vast majority of these tissues (45 of 54) expressed no detectable PDCD4 protein whereas the other nine glioma tissues showed decreased PDCD4 expression compared with normal brain tissues adjacent to the tumour, which showed strong PDCD4 expression. Collectively, 81% (68 of 84) of glioma tissues we examined lacked detectable PDCD4 protein expression (Table 1), indicating that loss of PDCD4 expression is a frequent event in primary gliomas. Consistent with this view, Jansen et al. reported that all of five tumour cell lines derived from central nerve system lacked PDCD4 expression [17].

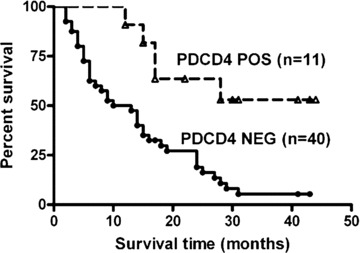

Furthermore, to assess the association of PDCD4 expression with patient survival, the survival data from 84 patients with gliomas (33 low grade and 51 high grade) were generated by a 3-year follow-up. We analysed the relationship between PDCD4 expression at protein level and clinicopathological characteristics in primary gliomas. The results showed that no significant correlation between PDCD4 expression and age, histological type or pathological grade existed (Table 1). The expression of PDCD4 was neither significantly associated with the survival rate of patients with a low grade of gliomas (n= 33) (data not shown). However, among 51 patients with high-grade gliomas, the expression of PDCD4 significantly correlated with the long-term survival rate of patients. The survival rate of patients with PDCD4-expressing gliomas was significantly higher than that of patients with PDCD4– gliomas (P= 0.0013) (Fig. 5). To examine whether the PDCD4 silencing was an independent unfavourable prognostic factor for patients, we performed a multivariant Cox regression analysis, including gender, age, histological types, grade and PDCD4 expression (Supporting Table S1). The level of PDCD4 expression could significantly predict the patient outcome independent of other clinicopathological variables for disease-specific survival (relative risk, 0.063; 95% confidence interval, 0.014–0.276, P < 0.0001). Thus, PDCD4 expression in primary gliomas can serve as an important factor for prognosis of high-grade gliomas. In addition, there appeared to be a tendency for PDCD4 expression to be associated with gender (see Table 1). The expression of PDCD4 in gliomas from male patients was significantly higher than that from female patients (P= 0.0245).

Fig 5.

Prognostic value of PDCD4 expression for patients with gliomas. The survival times of 51 patients with high-grade gliomas were analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The difference in survival time between patients with PDCD4+ gliomas and patients with PDCD4– gliomas is statistically significant (P < 0.05) as determined by the log-rank test.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that the tumour suppressor PDCD4 was frequently silenced in primary gliomas and glioma cell lines, and that this silencing may be caused by 5′ CpG island methylation. By analysing a large cohort of patients with gliomas, we further concluded that PDCD4 expression might serve as a prognostic factor in patients with high-grade gliomas. Although our current study focused only on gliomas, the findings reported here may also apply to other tumours as well. It has been reported that PDCD4 expression showed a progressive decrease in several human tumour cell lines [17, 30]. Furthermore, loss or reduction of PDCD4 expression was detected in human primary tumour tissues including lung cancer [18], hepatocellular carcinomas [19] and pancreatic cancer [20]. However, to date, the mechanism of PDCD4 silence in tumours is unclear.

Hypermethylation in 5′CpG island has been found in many tumours, which is often associated with the inactivation of cancer-related genes such as p16[31, 32], PTEN[33] and EMP3[34]. In the present study, we provide evidence to demonstrate, for the first time, that 5′CpG island methylation contributes to PDCD4 silencing at mRNA levels in gliomas. Non-tumour brain tissues and gliomas with PDCD4 expression showed undetectable methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island. In contrast, both glioma cell lines and all of glioma tissues without PDCD4 mRNA expression showed clear PDCD4 5′CpG island methylation (Fig. 1 and Table 2). PDCD4 gene silencing at mRNA levels was significantly associated with 5′CpG island methylation. Importantly, this silencing could be reversed by treating glioma cells with the methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Fig. 2). Consistent with this view, Fan et al. reported that DNA methyltransferase 1 knockdown induced re-expression of many genes including PDCD4 by demethylation of methylated CpG in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line SMMC-7721 [35]. These data demonstrate that 5′CpG island methylation of PDCD4 is significantly associated with the silencing of gene expression in gliomas at mRNA levels. Is the methylation of the 5′CpG island of PDCD4 also responsible for gene silencing in other tumours? Our preliminary studies indicate that methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island was detected in the ovarian cancers with no PDCD4 expression (data not shown). The study by Fan et al. also suggests that methylation of the PDCD4 may exit in human hepatocellular carcinoma [35]. However, methylation status of PDCD4 5′CpG island in other cancer cells remains to be determined.

Our results indicate that methylation of PDCD4 5′CpG island only involves in silencing of PDCD4 mRNA but do not affect the expression of PDCD4 protein. Dorrello et al. find that degradation of PDCD4 protein in response to stimulation, such as mitogens, may decrease levels of PDCD4 protein [22]. Some recent reports showed that MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) may post-transcriptionally down-regulate PDCD4 expression in human tumours, such as colorectal cancer and breast cancer [21, 36]. It has been known that microRNA (miR-21) is also overexpressed in gliomas, suggesting that microRNA (miR-21) may influence PDCD4 protein levels in gliomas. However, further investigation should be done in future.

We demonstrated that restoration of PDCD4 expression in glioma cell lines inhibited their proliferation and prevented their colony formation in vitro. To clarify whether PDCD4 expression in primary gliomas also affects tumorigenesis, we divided patients with gliomas into two groups: low-grade group (grades I and II) and high-grade group (grade III and IV) according to the WHO classification system, and then analysed the association of PDCD4 expression (detected by immunohistochemistry) with clinicopathological characteristics and patient survival over a period of 3 years. Our data indicated that PDCD4 expression was associated with long-term survival of patients with high-grade gliomas and was an independent favourable prognostic factor for patients while it had no relationship with grade or stage in gliomas. This result is not entirely consistent with a report about human primary lung cancer in which down-regulation of PDCD4 protein was significantly associated with the grade and stage of the cancer [18]. These results indicate that the role of PDCD4 in carcinogenesis may be tissue specific. The mechanisms through which PDCD4 expression affects tumorigenesis may vary in different tumours. PDCD4 might induce apoptosis of human breast cancer cell line T-47D [30], human hepatocellular carcinoma-derived cell line Huh7 [19]in vitro and enhance the apoptosis of murine lung cancer cells and control their cell cycles in K-ras null mice or AP-1 luciferase reporter mice [37, 38]. We found that reintroduction of PDCD4 in glioma cell lines could also induce their apoptosis and block cell cycle progression (see Fig. 3E and F). However, PDCD4 expression does not affect cell cycle or apoptosis in colon carcinoma cells [39]. Other researchers demonstrated that overexpression of PDCD4 could enhance the sensitivity of renal cancer cell lines to geldanamycin [17]. Our studies showed that overexpression of PDCD4 could enhance the sensitivity of ovary cancer-derived cell lines to cisplatin (data not shown). It suggested that PDCD4 might prolong the survival of patients through enhancing the sensitivity of tumour cells to chemotherapy. In addition, our analysis of the 5′CpG island of PDCD4 using genomatix promoter database (http://www.genomatix.de/products/index.html), indicates that PDCD4 may be an important target for other tumour suppressor genes. Many genes including some oncogenes or tumour suppressor genes, such as p53 could bind to 5′CpG island of PDCD4. Therefore, these genes might inhibit the cell proliferation by down-regulating or up-regulating expression of PDCD4. So the different status of other related genes among various tumours may affect the effect of PDCD4.

Unexpectedly, our data indicate that PDCD4 expression was significantly higher in gliomas of male patients than in that of female (see Table 1), suggesting that male hormones might up-regulate the PDCD4 expression. The previous report demonstrated that sex hormones and/or genetic differences between males and females may play a role in the pathogenesis of gliomas [40]. We noticed that sex-determining region Y (SRY), a transcription factor that initiates male sex determination, could bind to the regulatory region of PDCD4 5′CpG island. It suggests that the male hormones may up-regulate PDCD4 expression by SRY. However, the mechanisms by which that male hormone regulates PDCD4 expression remained to be clarified.

In summary, the frequent inactivation of PDCD4 at mRNA level in gliomas was significantly associated with 5′CpG island methylation. The restoration of PDCD4 expression in glioma cell lines inhibited their proliferation and prevented their colony formation. Furthermore, PDCD4 expression in primary glioma tissues is associated with better prognosis of patients with high-grade gliomas. Therefore, PDCD4 reactivation might be an effective new strategy for the treatment of gliomas.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30628015) and (No. 30671976) and National ‘973’ program (No. 2006CB503803). We thank greatly Dr. N. H. Colburn (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA) for kindly providing the anti-PDCD4 antibody and Dr. Ozaki (Department of Internal Medicine, Saga Medical School, Saga University, Saga, Japan) for the PDCD4 expression plasmids.

References

- 1.Bansal K, Liang ML, Rutka JT. Molecular biology of human gliomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2006;5:185–94. doi: 10.1177/153303460600500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakabayashi H, Hara M, Shimuzu K. Clinicopathologic significance of cystatin C expression in gliomas. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, et al. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6892–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao F, Zhang P, Zhou C, et al. Frequent loss of PDCD4 expression in human glioma: possible role in the tumorigenesis of glioma. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibahara K, Asano M, Ishida Y, et al. Isolation of a novel mouse gene MA-3 that is induced upon programmed cell death. Gene. 1995;166:297–301. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuhashi S, Yoshinaga H, Yatsuki H, et al. Isolation of a novel gene from a human cell line with Pr-28 Mab which recognizes a nuclear antigen involved in the cell cycle. Res Commun Biochem Cell Mol Biol. 1997;1:109–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlichter U, Burk O, Worpenberg S, et al. The chicken Pdcd4 is regulated by v-Myb. Oncogene. 2001;20:231–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Göke A, Göke R, Knolle A, et al. DUG is a novel homologue of translation initiation factor 4G that binds eIF4A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cmarik JL, Min H, Hegamyer G, et al. Differentially expressed protein Pdcd4 inhibits tumor promoter-induced neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14037–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhar A, Young MR, Colburn NH. The role of AP-1, NF-kappaB and ROS/NOS in skin carcinogenesis: the JB6 model is predictive. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002:234–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang HS, Knies JL, Stark C, et al. PDCD4 suppresses tumor phenotype in JB6 cells by inhibiting AP-1 transactivation. Oncogene. 2003;22:3712–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilliard A, Hilliard B, Zheng SJ, et al. Translational regulation of autoimmune inflammation and lymphoma genesis by programmed cell death 4. J Immunol. 2006;177:8095–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen AP, Camalier CE, Colburn NH. Epidermal expression of the translation inhibitor programmed cell death 4 suppresses tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6034–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bitomsky N, Bohm M, Klempnauer KH. Transformation suppressor protein PDCD4 interferes with JNK-mediated phosphorylation of c-Jun and recruitment of the coactivator p300 by c-Jun. Oncogene. 2004;23:7484–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang HS, Matthews CP, Clair T, et al. Tumorigenesis suppressor PDCD4 down-regulates mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 1 expression to suppress colon carcinoma cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1297–306. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1297-1306.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang HS, Jansen AP, Komar AA, et al. The transformation suppressor Pdcd4 is a novel eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A binding protein that inhibits translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:26–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.26-37.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen AP, Camalier CE, Stark C, et al. Characterization of programmed cell death 4 in multiple human cancers reveals a novel enhancer of drug sensitivity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:103–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Knösel T, Kristiansen G, et al. Loss of PDCD4 expression in human lung cancer correlates with tumour progression and prognosis. J Pathol. 2003;200:640–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, Ozaki I, Mizuta T, et al. Involvement of programmed cell death 4 in transforming growth factor-beta1-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:6101–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma G, Guo KJ, Zhang H, et al. Expression of programmed cell death 4 and its clinicopathological significance in human pancreatic cancer. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2005;27:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asangani IA, Rasheed SA, Nikolova DA, et al. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2128–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorrello NV, Peschiaroli A, Guardavaccaro D, et al. S6K1- and betaTRCP-mediated degradation of PDCD4 promotes protein translation and cell growth. Science. 2006;314:428–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1130276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteller M. CpG island hypermethylation and tumor suppressor genes: a booming present, a brighter future. Oncogene. 2002;21:5427–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baylin SB, Herman JG. DNA hypermethylation in tumorigenesis: epigenetics joins genetics. Trends Genet. 2000;16:168–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chadderton T, Wilson C, Bewick M, et al. Evaluation of three rapid RNA extraction reagents: relevance for use in RT-PCR’s and measurement of low level gene expression in clinical samples. Cell Mol Biol. 1997;43:1227–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culley DE, Kovacik WP, Jr, Brockman FJ, et al. Optimization of RNA isolation from the archaebacterium Methanosarcina barkeri and validation for oligonucleotide microarray analysis. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;67:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1427–31. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myöhänen S, et al. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afonja O, Juste D, Das S, et al. Induction of PDCD4 tumor suppressor gene expression by RAR agonists, antiestrogen and HER-2/neu antagonist in breast cancer cells. Evidence for a role in apoptosis. Oncogene. 2004;23:8135–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, et al. 5′ CpG islands methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumour suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nat Med. 1995;1:686–92. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SH, Jung KC, Ro JY, et al. 5′ CpG islands methylation of p16 is associated with absence of p16 expression in glioblastomas. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:555–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.5.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baeza N, Weller M, Yonekawa Y, et al. PTEN methylation and expression in glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;106:479–5. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alaminos M, Dávalos V, Ropero S, et al. EMP3, a myelin-related gene located in the critical 19q13.3 region, is epigenetically silenced and exhibits features of a candidate tumor suppressor in glioma and neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2565–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan H, Zhao Z, Quan Y, et al. DNA methyltransferase 1 knockdown induces silenced CDH1 gene reexpression by demethylation of methylated CpG in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line SMMC-7721. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:952–61. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282c3a89e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankel LB, Christoffersen NR, Jacobsen A, et al. Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1026–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin H, Kim TH, Hwang SK, et al. Aerosol delivery of urocanic acid-modified chitosan/programmed cell death 4 complex regulated apoptosis, cell cycle, and angiogenesis in lungs of K-ras null mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1041–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang SK, Jin H, Kwon JT, et al. Aerosol-delivered programmed cell death 4 enhanced apoptosis, controlled cell cycle and suppressed AP-1 activity in the lungs of AP-1 luciferase reporter mice. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1353–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q, Sun Z, Yang HS. Downregulation of tumor suppressor Pdcd4 promotes invasion and activates both beta-catenin/Tcf and AP-1-dependent transcription in colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:1527–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKinley BP, Michalek AM, Fenstermaker RA, et al. The impact of age and sex on the incidence of glial tumors in New York state from 1976 to 1995. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:932–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]