Abstract

Objective

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a rare cause of acute diffuse blistering in the adult patient. It commonly presents with subepidermal blistering, epidermal necrosis, and symptoms of mucosal irritation, such as conjunctivitis and vaginal ulceration. Because of its rarity, it is frequently misdiagnosed as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. Here, we will describe clinical and histologic manifestations of paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Methods

This case report describes a 45 year old female with paraneoplastic pemphigus who was admitted to and treated in a burn intensive care unit.

Results

Although initially diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the patient had progression of desquamation when potentially offending medications were discontinued. Diffuse adenopathy was noted on examination and biopsy confirmed a low grade lymphoma.

Conclusions

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a rare but important cause of acute diffuse blistering in adults. This disorder should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with diffuse blistering.

Keywords: Paraneoplastic pemphigus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Toxic epidermal necrolysis

CASE PRESENTATION

A 45 year old previously healthy female presented with a chief complaint of a skin rash and mucosal ulcers unresponsive to treatment. Six weeks prior to admission, the patient had noted eye irritation with dry eye sensation followed by bronchitis symptoms. She was prescribed a three day course of azithromycin and levofloxacin followed by doxycycline for persistent symptoms. She subsequently developed mouth sores and a progressive rash extending to her entire body; all medications were discontinued due to suspicion of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). She was admitted to an outside hospital where a skin biopsy demonstrated epidermal necrosis consistent with erythema multiforme. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed non-specific immunoglobulin deposition. Intravenous steroids were administered for nine days with improvement in symptoms and the patient was discharged on an oral steroid taper. At home, she noted progression of her rash with worsening eye irritation, vaginal ulceration, and a twenty-two pound weight loss. As a result, she was referred to our institution, a tertiary referral academic burn center.

On admission, the patient’s skin had diffuse erythematous patches with patchy areas of superficial desquamation. Additionally, there were several superficial erosions on her back and extremities. Erythematous to violaceous macules and patches were noted on the palms and soles bilaterally. A single unruptured blister measuring less than 1 cm in diameter was present on the left upper extremity; Nikolsky sign was negative. These skin changes collectively involved approximately 90% of her total body surface area. Less than 20% of involved skin demonstrated superficial desquamation. There were crusted, hemorrhagic erosions on the lips with extension onto the vermillion. Intraoral examination revealed superficial oral ulcerations which involved her tongue, hard palate, buccal mucosa, and gums. The external genitals had mild erythema with superficial erosion on the labia minora. Figure 1 demonstrates the patient’s appearance on hospital day five at our institution.

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation of patient with acute, diffuse blistering. Images were obtained on hospital day five at our institution.

The patient was admitted to the Burn Intensive Care Unit for fluid and electrolyte resuscitation, topical antimicrobials, and dressing changes. Acticoat (Smith & Nephew, Hull, England) was applied to raw skin surfaces while mineral oil and bacitracin were applied to dry skin. The wounds remained clean without signs of infection during the patient’s hospitalization. Methylprednisolone was administered for suspected autoimmune blistering disorder, replacing the previously prescribed oral prednisone taper.

After intravenous steroid administration, the patient noted improvement of her bronchitis symptoms. She did not exhibit signs or symptoms consistent with esophageal slough and tolerated a soft mechanical diet with adequate caloric intake. While on steroids, she developed ulcerative lesions along her labia minora and vaginal mucosa which were treated with petroleum jelly with lidocaine for symptomatic relief. Ophthalmology consultation showed the presence of filamentary keratitis which was treated with erythromycin drops, lacrilube and prednisolone drops.

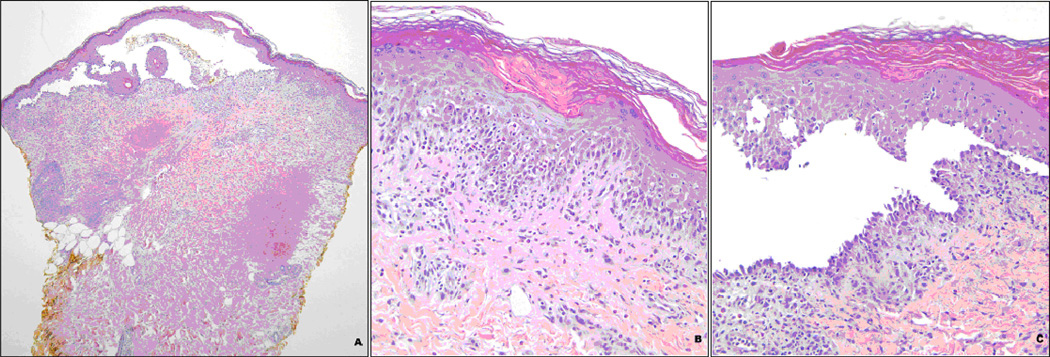

Two punch biopsies of the left thigh skin were performed and sent for DIF and hematoxlyn and eosin staining. Routine histology showed florid interface dermatitis, with frequent dyskeratotic keratinocytes, as well as suprabasilar clefting and focal acantholysis. Numerous eosinophils were present in the dermis and epidermis as well as in the cleft cavity. DIF studies revealed linear basement zone deposition of IgG, patchy intercellular deposition of IgG, and cytoid bodies composed of various immunoreactants. While the interface changes and cytoid bodies suggested a process such as erythema multiforme, the suprabasilar clefting, acantholysis, and intercellular deposition of IgG were more in keeping with pemphigus. Together, the overlapping features suggested paraneoplastic pemphigus. Serologic studies were positive for antibodies against both desmoglein 1 and 3, supporting the diagnosis. Selected histologic images are demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Histology of Skin Biopsy

a. Skin biopsy demonstrating suprabasilar bulla (H&E, 40×).

b. Interface reaction reminiscent of erythema multiforme with infiltration by eosinophils (H&E, 200×).

c. Suprabasilar cleft with some acantholysis (H&E, 200×).

Subsequent targeted physical examination disclosed extensive diffuse lymphadenopathy, with particular prominence in the left axilla; computed tomography revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen and pelvis, and a large soft tissue mass infiltrating the mesentery, compatible with lymphoma. Biopsy of the left sided axillary lymph nodes demonstrated grade I follicular lymphoma.

Based on the diagnosis of PNP secondary to low grade follicular lymphoma, chemotherapy with rituxan was initiated. A bone marrow biopsy was ordered for pre-treatment evaluation. PET scan demonstrated 2-deoxy-2-(F-18) fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) avid thoracic, abdominal, pelvic and mesenteric disease concerning for neoplasm. An additional intensely avid focus of FDG uptake was noted in the left thyroid lobe corresponding to a thyroid lesion with rim like calcification.

The patient was discharged eight days later for outpatient management of her lymphoma.

DISCUSSION

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

PNP is a life-threatening autoimmune disease associated with lymphoproliferative neoplasms and characterized by mucosal and skin lesions. The differential diagnosis includes SJS, TEN, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus folaceus, bullous pemphigoid, acute graft versus host disease, and linear IgA dermatosis.1 The course of the disease may involve multiple organ failure, sepsis, or respiratory complications; the associated mortality rate is reported as approximately 90 percent in the literature.2 This syndrome was originally described in 1990 by Anhalt and colleagues in a case series of five patients. The following diagnostic criteria were established: intractable stomatitis and polymorphous skin lesions; epidermal acantholysis with associated keratinocyte necrosis; deposition of IgG and complement in the epidermal intracellular spaces and granular/linear complement deposition in the basement membrane zone; the presence of serum autoantibodies against skin and transitional epithelium; and immunoprecipitation of several plakin proteins, a group of proteins that mediate attachment of cytoskeletal filaments to transmembrane adhesion molecules.2–3

The pathophysiology of PNP is related to an autoimmune attack by tumor-derived autoantibodies against multiple antigens in the epithelial tissues.4 One of the characteristic features in PNP is the presence of serum autoantibodies which recognize proteins in stratified squamous epithelia as well as transitional columnar and simple epithelia.5

Clinical presentation of paraneoplastic pemphigus

The hallmark clinical feature of PNP is early mucosal involvement, usually affecting the entire oral cavity, tongue, and lips, or other mucosal surfaces. These painful lesions are usually poorly responsive to treatment. Skin lesions generally present later and take on a wider variety of appearances. Blisters tend to erupt on the trunk, head and neck, and proximal extremities; these lesions generally present as erosions. Lesions on distal extremities are more likely to develop as tense blisters. Lichenoid skin lesions are also commonly seen on the trunk and extremities,6 which may resemble SJS or graft-versus-host disease. In addition, these skin findings frequently change throughout the course of illness.4 Blistering of stratified squamous epithelium results from acantholysis, the loss of cell–cell adhesion, induced by pathogenic antibodies against the desmogleins.7

Diagnosis and management of paraneoplastic pemphigus

The critical steps to diagnosis and management of PNP include high clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, complete tumor resection, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) administration. Tumors associated with PNP include non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Castleman’s tumor, chronic lymphocytic leukemia,2,4 or less commonly solid tumors such as squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina, tongue, or skin.8–10 Due to the hematogenous spread of autoantibodies derived from the tumor, vascular exclusion should be performed during the surgery. Intra-operative tumor manipulation should be minimized. Administration of IVIG before, during and after the operation is recommended to block the circulating autoantibodies released from the tumor.4

Skin lesions should be initially treated using topical antimicrobials. Mucosal lesions often require subspecialist consultation, including ophthamology, obstetrics-gynecology, urology, and/or pulmonary. Skin lesions usually improve markedly within six to twelve weeks, but mucosal lesions tend to persist and several months may be required for recovery. Up to one third of patients with this syndrome will develop the clinical features of bronchiolitis obliterans. This presentation is frequently fatal. The possible causes include infection, the toxic effects of chemotherapy, or autoantibody-mediated pulmonary injury.2

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Clinical presentation of SJS/TEN

The initial presentation of SJS and TEN can be nonspecific, including fever, headache, and chills. Symptoms of mucosal irritation, such as conjunctivitis, dysuria, and dysphagia can also be present. After a two or three day prodrome, both mucosal and cutaneous lesions appear. Two or more mucous membranes, including vaginal, urinary, respiratory, gastrointestinal, oral, and conjunctival, are typically involved.1 Cutaneous lesions are classically described as diffuse erythematous macules with purpuric, necrotic centers. Blisters coalesce and demonstrate a positive Nikolsky’s sign, though often flaccid on presentation.12, 13 TEN can also present with subepidermal blistering associated with full thickness epidermal necrosis.13 Table 1 describes the SJS/TEN classification spectrum.

Table 1.

Consensus classification of the SJS/TENS spectrum 22

| SJS | Detachment less than 10% TBSA with widespread erythematous or purpuric macules or flat atypical targets. |

| Overlap SJS-TEN | Detachment 10–30% TBSA with widespreal purpuric macules or flat atypical targets. |

| TEN with spots | Detachment of greater than 30% TBSA with widespread purpuric macules or flat atypical targets. |

| TEN without spots | Detachment of greater than 10% TBSA with large epidermal sheets and without purpuric macules or targets. |

A single offending agent or drug is identified in less than 50% of cases,14 although sulfonamides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, carbamazepine, oxican NSAIDS, and chlormezanone are the most common.14, 15 A rash associated with a new drug administration is not specific to SJS/TEN; it can also be secondary to drug-induced pemphigus or IgA dermatosis.16 Antibiotic-associated SJS/TEN typically presents one week after drug administration as compared to two months in cases associated with anti-convulsant medications.1

Diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN

Initial treatment involves discontinuation of all potentially offending drugs and transfer to a burn center.12 Burn ICU admission for temperature regulation, dressing changes, and fluid and electrolyte resuscitation is recommended. Flaccid bullae should undergo debridement with placement of temporary coverage when large wounds are present. Empiric systemic antibiotics are not indicated as they have been associated with increased mortality,14 although topical antimicrobials are appropriate. Hemodialysis to remove potentially offending drugs with long half lives should be considered. Ophthalmologic consultation is warranted as over fifty percent of SJS/TEN patients develop serious ocular complications such as symblepharon or entropion.16

Microscopically, SJS demonstrates vacuolization of the basal layer keratinocytes with lymphocyte deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. Necrotic spinous layer keratinocytes and an absence of IgA deposition are also seen.13

The controversy of treatment regimens involving steroids, immuno-suppression, and immuno-modulation are beyond the scope of this article and are well reviewed elsewhere.1, 12–13, 17, 18 The immunology of SJS/TEN has similarly been well reviewed elsewhere.17 Briefly, TEN is known to have increased expression of the FAS ligand which promotes keratinocyte apoptosis by binding to the FAS (CD95) death receptor. The mechanism of IVIG treatment is blockade of CD95, and IVIG has been associated with rapid reversal and favorable recovery in small series of TEN patients.19 Although IVIG data is controversial,21, 22 it has minimal toxicities and should be considered in appropriate patients.1 SJS mortality has been estimated at 1 – 5% and TEN mortality at 25 – 44%.1, 12, 14

CONCLUSIONS

In our case report, a patient with paraneoplastic pemphigus misdiagnosed as SJS was successfully diagnosed and treated in a burn ICU. While the initial presentation and management of PNP may be similar to that of SJS/TEN, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, or lichen planus, there is no response to cessation of medications in patients with PNP. This necessitates further workup for an alternative etiology which will then permit the correct diagnosis and ultimately the appropriate therapy. We have reviewed the pathophysiology and comparative treatment approaches for these two conditions which can be easily confused in the critical care setting. Managing such patients in a verified Burn center allows for the greatest utility of resources available for resuscitation and administering multidisciplinary wound and patient care within a single setting with critical care capabilities.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support

Dr. Pannucci received salary support through NIH grant T32 GM-08616.

Contributor Information

Dr. Awori J Hayanga, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

Timothy M Lee, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

Christopher John Pannucci, Section of Plastic Surgery, University of Michigan.

Brian S Knipp, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

Stephen H Olsen, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan.

Stewart C Wang, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

Lena M Napolitano, Division of Acute Care Surgery, University of Michigan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2007;26:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nousari HC, Deterding R, Wojtczack H, Aho S, Uitto J, Hashimoto T, Anhalt GJ. The mechanism of respiratory failure in paraneoplastic pemphigus. N Engl J. Med. 1999 May 6;340(18):1406–1410. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JR, Korman NJ, Jabs DA, Kory M, Izumi H, Ratrie H, 3rd, Mutasim D, Ariss-Abdo L, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. An autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J. Med. 1990 Dec 20;323(25):1729–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012203232503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu X, Zhang B. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Dermatol. 2007 Aug;34(8):503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anhalt GJ. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004 Jan;9(1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsiao CJ, Hsu MM, Lee JY, Chen WC, Hsieh WC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in association with a retroperitoneal Castleman's disease presenting with a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. A case report and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2001 Feb;144(2):372–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amagai M, Nishikawa T, Nousari HC, Anhalt GJ, Hashimoto T. Antibodies against desmoglein 3 (pemphigus vulgaris antigen) are present in sera from patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus and cause acantholysis in vivo in neonatal mice. J Clin Invest. 1998 Aug 15;102(4):775–782. doi: 10.1172/JCI3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perniciaro C, Kuechle MK, Colón-Otero G, Raymond MG, Spear KL, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a case of prolonged survival. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994 Sep;69(9):851–855. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rongioletti F, Truchetet F, Rebora A. Paraneoplastic pemphigoid-pemphigus? Subepidermal bullous disease with pemphigus-like direct immunofluorescence. Int J Dermatol. 1993 Jan;32(1):48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong KC, Ho KK. Pemphigus with pemphigoid-like presentation, associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Australas J Dermatol. 2000 Aug;41(3):178–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2000.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Zhu X, Li R, Tu P, Wang R, Zhang L, Li T, Chen X, Wang A, Yang S, Wu Y, Yang H, Ji S. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor: a commonly reported subtype of paraneoplastic pemphigus in China. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Oct;141(10):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotliar J. Approach to the patient with a suspected drug eruption. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2007;26:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazin R, Ibrahimi OA, Hazin MI, et al. Stevens-johnson syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann. Med. 2008;40:129–138. doi: 10.1080/07853890701753664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz JT, Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, et al. A 10-year experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21:199–204. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200021030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al. Medication use and the risk of stevens-johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1600–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain W, Craven NM. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and stevens-johnson syndrome. Clin. Med. 2005;5:555–558. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.5-6-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chave TA, Mortimer NJ, Sladden MJ, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Current evidence, practical management and future directions. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005;153:241–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalili B, Bahna SL. Pathogenesis and recent therapeutic trends in stevens-johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:272–280. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60789-2. quiz 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science. 1998;282:490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittmann N, Chan B, Knowles S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin use in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis and stevens-johnson syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2006;7:359–368. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faye O, Roujeau JC. Treatment of epidermal necrolysis with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (IV ig): Clinical experience to date. Drugs. 2005;65:2085–2090. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, stevens-johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch. Dermatol. 1993;129:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]