Abstract

Background

A significant fraction of OPSCCA cases is associated with traditional carcinogens; in these patients treatment response and clinical outcomes remain poor.

Methods

We evaluated patient, tumor and treatment characteristics for 200 veterans with OPSCCA treated at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) between 2000 and 2012.

Results

Most patients (77%) were white and heavy smokers. Twenty seven patients required tracheostomy and 63 required gastrostomy placement during treatment. Overall survival at 5 years was 40%.. Survival was impacted by T stage, treatment intensity, completion of treatment and p16 tumor status. Almost 30% of patients were unable to complete a treatment regimen consistent with NCCN guidelines.

Conclusions

OPSCCA in veterans is associated with traditional carcinogens and poor clinical outcomes. Despite heavy smoking exposure, p16 tumor status significantly impacts survival. Careful consideration must be given to improving treatment paradigms for this cohort given their limited tolerance for treatment escalation.

Keywords: oropharyngeal cancer, smoking, veteran, tracheostomy, gastrostomy

INTRODUCTION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx (OPSCCA) affects nearly 20,000 patients annually in the US alone.(1) Over the last two decades, the number of new diagnoses of OPSCCA has increased at an alarming rate.(1, 2) Partially alleviating this increase is mounting evidence that clinical outcomes for patients with OPSCCA overall are improving.(2–6) In large part, improved outcomes appear to be driven by the underlying biology of OPSCCA, specifically, the role of human papilloma virus (HPV). Approximately two thirds to three quarters of new OPSCCA diagnoses are associated with HPV(2). For these patients, 5 year survival rates of 70 to 90% are observed.(7) Because of improved clinical outcomes, current efforts are underway to test the viability of de-escalation of treatment regimens.(8)

Despite improvements in clinical outcomes for patients with HPV driven OPSCCA, a significant proportion of new OPSCCA diagnoses appear to be associated with traditional carcinogen exposure such as tobacco and alcohol.(2) Clinical outcomes for this group of patients have remained largely unchanged over the last 40 years, despite advances in treatment strategies.(2) We have recently completed a detailed analysis of patients diagnosed with laryngeal SCCA at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC).(9) Our analysis demonstrated that veterans with laryngeal SCCA are older and have a more extensive carcinogen exposure than is encountered in the general population.(9) Based on these data and our clinical experience, we hypothesized that veterans with a diagnosis of OPSCCA would reflect the traditional characteristics of non-HPV related disease, resulting in substantially poorer clinical outcomes compared to the population at large. To test this hypothesis we completed a retrospective analysis of new diagnoses of OPSCCA at MEDVAMC over a 12 year time period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Following approval by the Baylor College of Medicine and the MEDVAMC institutional review boards, we reviewed the medical records of all patients with previously untreated oropharyngeal SCCA treated at the MEDVAMC between January 1, 2000 and April 1, 2012. Exclusion criteria included previous treatment of disease. Demographic information was recorded, including age, gender, marital status, race, smoking history, and alcohol consumption. Clinical pathologic features were collected including clinical stage according to the American Joint Commission on Cancer staging system and tumor grade of initial biopsy specimens. Results of diagnostic procedures, including imaging results, biopsies and fine-needle aspirations, were recorded as well as the treatments rendered and the associated dates. Operative notes were reviewed and the extent of surgical intervention was recorded.

Treatment

A multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board consisting of head and neck surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists determines the treatment plan for all head and neck cancer patients. Tumor board recommendations are intended to be compliant with current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, but they are also guided by the patient’s ability to tolerate the proposed treatment in light of existing comorbidities and treatment for previous or co-existing malignancies.

P16 testing

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy tissue blocks were retrieved from the archive maintained at the MEDVAMC Department of Pathology. Two contiguous 5 μm sections were cut from each FFPE block. One section was stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin and reviewed by a surgical pathologist (SL) to confirm the original histopathological diagnosis and to ensure tumor adequacy. The paraffin sections were mounted on positively charged slides, deparaffinized in Bond Dewax Solution (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, United Kingdom) and rehydrogenized in descending grades (100–70%) of ethanol. Endogenous peroxide activity was blocked by pretreatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, and antigen recovery was achieved by 20 minutes heat-induced epitope retrival. Immunostains were performed using an automated tissue-staining system (Bond Polymer Refine Detection System -Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, United Kingdom). Tissue sections were stained with p16 antibody following manufacturer’s instruction (Vantana, Tucson, Arizona). Bound p16 antibody was detected using the 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) Chromogen Kit (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, United Kingdom). Appropriate positive and negative controls were performed. Each slide was evaluated by a trained head and neck clinical pathologist (SL) who was blinded to the clinical data associated with each specimen. P16 positivity was ascertained according to current institutional standards.

Study End Points and Statistical Analysis

End points included time to recurrence and death. Imaging was used as a surrogate in the absence of a pathological report documenting recurrence. DFS (date of primary diagnosis to date of recurrence or death) and OS (date of recurrence to last documented hospital note) were also recorded. Patients suspected of recurrence were restaged using clinical exam, imaging and when possible, biopsy. Actuarial survival rates were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between groups were made using log-rank statistics. Univariate analysis was performed using Chi square analysis for risk factors associated with tracheostomy and gastrostomy. Multivariate Cox regression was used for DFS and OS using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Of those patients undergoing primary surgery, patients treated with XRT or chemo-XRT were included as such in their respective treatment groups for the multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 200 patients were evaluated with a mean age of 60.8 years (Table 1). All patients were male. Almost a quarter of patients were African American (23%). Mean and median follow up for this cohort were 2.8 and 1.8 years, respectively. A majority of patients were single at the time of diagnosis. Patients demonstrated high rates of exposure to known carcinogens; the average pack year history for the cohort was 52, with an average alcohol consumption of 5 drinks per day. Of patients who smoked, 92% had a lifetime smoking history of >10 pack years; of patients who consumed alcohol, 42% consumed an average of more than 5 drinks per day.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patients | 200 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean age (yr) | 60.8 | |

|

| ||

| Number | % | |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| married | 79 | 40 |

| single | 121 | 60 |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| male | 200 | 100 |

| female | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| white | 154 | 77 |

| black | 45 | 23 |

| other | 1 | 0.5 |

|

| ||

| Risk factors | ||

| tobacco use | 178 | 89 |

| alcohol use | 174 | 88 |

Tumor stage at presentation was fairly evenly distributed among various T stages (Table 2), although the most common presenting N stage was N2 and approximately 70% of all patients exhibited greater than N1 disease burden in the neck. The most common subsites for the primary tumor were tonsil and base of tongue, and most tumors were either moderately (40%) or poorly (55%) differentiated at the time of presentation. Fifty one patients (25%) had a history of second malignancy. Of these, 19 had a history of second upper aero-digestive tract (UAEDT) malignancy with the most common histology being squamous cell carcinoma. The presence of a concurrent second malignancy or previous UAEDT malignancy restricted the available treatment options in these patients.

Table 2.

Tumor characteristics

| Patients | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| T stage | ||

| 1 | 28 | 14 |

| 2 | 58 | 29 |

| 3 | 53 | 27 |

| 4 | 58 | 29 |

|

| ||

| N stage | ||

| 0 | 49 | 25 |

| 1 | 16 | 8 |

| 2 | 120 | 60 |

| 3 | 15 | 8 |

|

| ||

| M stage | ||

| 0 | 190 | 95 |

| 1 | 10 | 5 |

|

| ||

| SUBSITE | ||

| tonsil | 93 | 47 |

| base of tongue | 62 | 31 |

| palate | 30 | 15 |

| other | 15 | 8 |

|

| ||

| Differentiation | ||

| well | 8 | 5 |

| moderate | 64 | 40 |

| poor | 90 | 55 |

Treatment characteristics

As at most institutions, treatment for OPSCCA at the MEDVAMC consists primarily of radiotherapy (XRT) with or without concomitant chemotherapy based on disease stage. A total of 17 patients underwent surgical treatment. Of these patients, 5 underwent tonsillectomy, 6 underwent excision of a soft palate lesion, 2 underwent pre-irradiation neck dissections and 1 underwent a composite resection (glossectomy, palatectomy, mandibulectomy). Because the group of patients who were treated surgically was small, it was not included as a separate category in our basic survival or multivariate analysis. Five patients received induction chemotherapy. Patients with stage III–IV disease were treated with multimodality therapy unless contraindicated due to existing comorbidities or unless the patient refused the recommended treatment course. For patients treated with curative intent radiotherapy, the median dose delivered to the primary tumor was 70Gy with a median time to completion of 51 days. A total of 161 patients (80%) completed curative intent treatment (Table 3). Fifteen patients were slated for palliative treatment based on their disease stage and existing co-morbidities and 24 patients received no treatment, primarily due to patient refusal. Of patients who underwent curative treatment, 118 completed treatment (incomplete treatment was defined as: no chemotherapy despite being indicated according to NCCN guidelines, early cessation of treatment or missing 10 or more XRT sessions). Among patients which underwent curative treatment, 123 were treated with concurrent chemo-XRT, 30 received XRT alone and 14 were treated with surgery alone or followed by adjuvant XRT when indicated. A total of 169 patients were treated with XRT, of which 154 received curative intent, primary treatment. A total of 134 patients were treated with concurrent chemotherapy, of which 124 received curative intent, primary treatment. The most commonly utilized chemotherapeutic agent was cisplatin, followed by carboplatin. Of patients who were treated with curative intent, 70% were able to complete the recommended treatment in a manner consistent with NCCN guidelines.

Table 3.

Treatment characteristics.

| Patients | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Treatment | ||

| curative | 161 | 80 |

| Palliative/none | 39 | 20 |

|

| ||

| Radiation | ||

| primary | 154 | 77 |

| adjuvant | 7 | 3.5 |

| palliative | 8 | 4 |

| None | 31 | 15.5 |

|

| ||

| Chemotherapy | ||

| primary | 124 | 62 |

| adjuvant | 0 | 0 |

| palliative | 10 | 5 |

| none | 66 | 33 |

Functional outcomes

A significant portion of patients presented with advanced disease at the primary site, resulting in substantial loss of pharyngeal function. As a result, 27 patients required tracheostomy at some point during their treatment, of which 23 were performed prior to treatment initiation. Of these, 18 were performed in patients with T4 tumors. A total of 63 patients required PEG placement for nutritional support, of which 47 were placed prior to treatment initiation. Of these, almost half (23) were performed in patients with T4 tumors. At last follow up, 63 patients had a current PEG and 23 patients still required a tracheostomy to maintain adequate ventilation. Gastrostomy and tracheostomy placement was associated with advanced T stage (T3–4, p<0.01) but not N stage (N>0); current gastrostomy and tracheostomy was associated with advanced T stage (T3–4, p<0.01) but not N stage (N>0). No other patient, tumor or treatment characteristics were associated with PEG or tracheostomy placement. PEG placement was also associated with treatment selection (p<0.01); 41% of patients treated with chemo-XRT required PEG placement compared to 16% of patients treated with XRT alone. Only 2 patients experienced documented osteo-radionecrosis of the mandible as a sequelae of treatment.

Recurrence and disease free survival

Within the entire patient cohort, a total of 108 patients experienced disease recurrence or progression; of these, recurrence/progression occurred locoregionally in 98 patients (91%) and distantly in 21 patients (11 patients recurred/progressed at both sites). Among the 161 patients treated with curative intent, 75 patients experienced recurrence/progression; 69 events occurred locoregionally (92%), and 13 occurred distantly (7 occurred both locoregionally and distally). Disease progression or recurrence was addressed primarily either via palliative treatment or supportive care. Fourteen patients were treated surgically for recurrence, while 14 were treated with XRT.

Survival

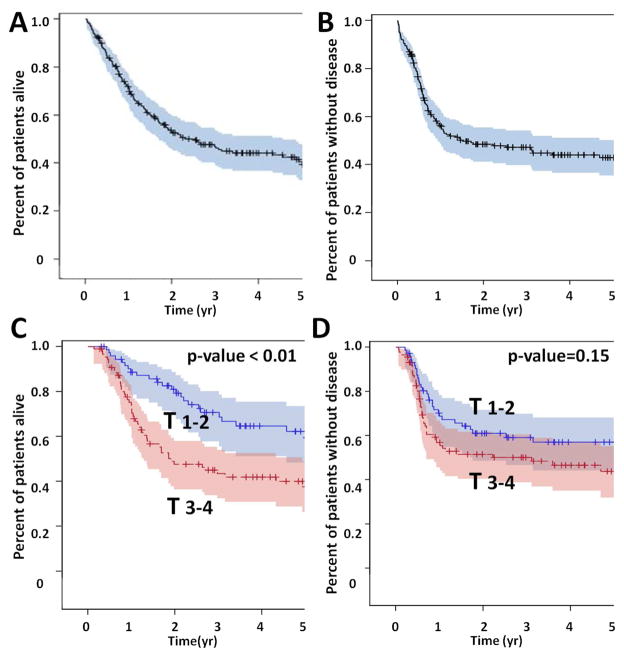

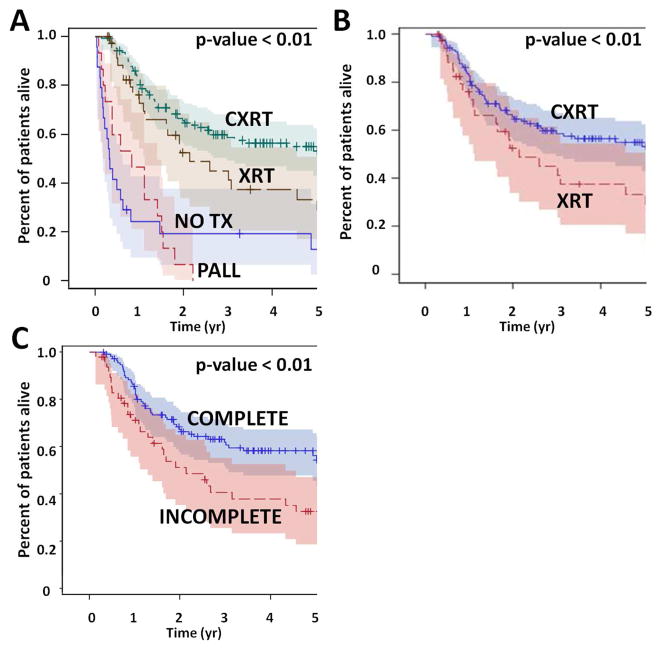

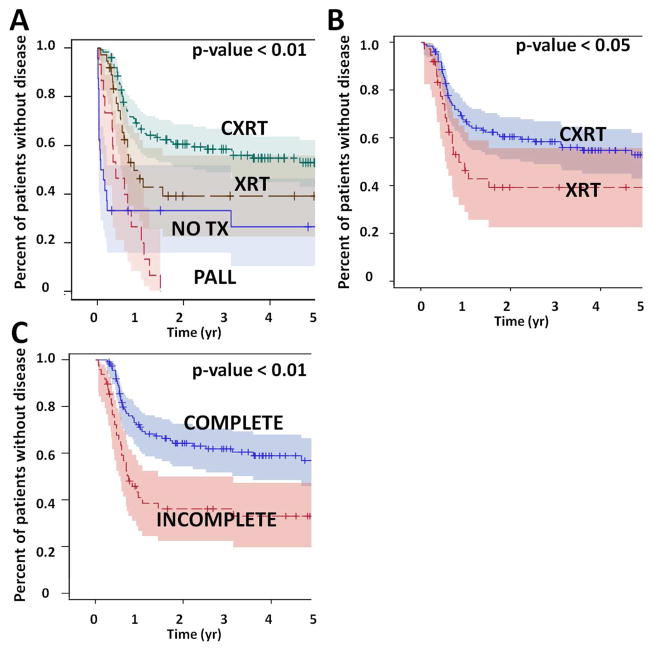

Overall survival (OS) for the entire patient cohort was 52% at 2 years and 40% at 5 years. Disease free survival (DFS) at 2 and 5 years was 48% and 43% respectively (Figure 1). Overall survival, but not disease free survival was impacted significantly by T stage; there was no statistically significant effect for N stage. Overall survival was also impacted significantly by treatment selection (Figure 2). Patients treated with concurrent chemo-XRT did significantly better compared to patients treated with XRT alone (53% OS at 5 years vs 29%), despite the fact that patients treated with chemo-XRT generally presented with more advanced disease. Patients which completed treatment had better OS (54% at 5 years) compared to those which did not (29%). Curative intent treatment, the addition of chemotherapy and completion of treatment were also significantly associated with improved disease free survival (Figure 3). On multivariate analysis, T stage (HR=2.3; 95%CI: 1.51–3.439) and treatment selection (XRT vs no tx HR=0.354; 95%CI: 0.186–0.673) significantly affected overall survival among all patients, as well as among those treated with curative intent (Table 4). Disease free survival was significantly affected by T stage (HR=1.687; 95%CI: 1.099–2.589) and N stage (HR=2.458; 95%CI: 1.362–4.438) as well as treatment selection (XRT vs no tx HR=0.322; 95%CI: 0.158–0.658) among all patients, and by treatment completion (HR=0.482; 95%CI: 0.283–0.818) among patients treated with curative intent.

Figure 1. Patient survival.

OPSCCA overall survival (OS) (A) and disease free survival (DFS) (B). Effect of T stage on OS (C) and DFS (D).

Figure 2. Treatment effect (overall survival).

Patients which received curative intent treatment had better survival compared to patients which did not (A). The addition of chemotherapy (B) and completion of the entire treatment regimen (C) was also associated with improved overall survival.

Figure 3. Treatment effect (disease free survival).

Patients which received curative intent treatment had better survival compared to patients which did not (A). The addition of chemotherapy (B) and completion of the entire treatment regimen (C) was also associated with improved disease free survival.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis.

A) Among all patients, T stage, p16 status and treatment selection had a significant impact on OS and DFS; DFS was also affected by N stage. B) Among patients treated with curative intent, T stage, p16 status and chemotherapy had a significant impact on OS, while completion of treatment and −16 status had a significant impact on DFS. (HR= hazard ration, CL= confidence limit)

| A

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Variable | Comparison group | HazardRatio | HRLowerCL | HRUpperCL | χ2 p-value |

| 70 and above | 40–49 | 2.143 | 0.894 | 5.137 | 0.087 |

| 60–69 | 40–49 | 1.120 | 0.471 | 2.664 | 0.798 |

| 50–59 | 40–49 | 0.737 | 0.320 | 1.701 | 0.475 |

| N > 0 | N = 0 | 1.676 | 0.981 | 2.866 | 0.059 |

| T 3–4 | T 1–2 | 2.279 | 1.510 | 3.439 | <0.0001 |

| Palliative tx | No tx | 0.863 | 0.389 | 1.916 | 0.717 |

| Chemo-XRT | No tx | 0.154 | 0.081 | 0.292 | <0.0001 |

| XRT | No tx | 0.354 | 0.186 | 0.673 | 0.002 |

| tobacco (yes) | tobacco (no) | 1.329 | 0.663 | 2.667 | 0.423 |

| P16unknown | P16− | 0.765 | 0.461 | 1.270 | 0.301 |

| P16+ | P16− | 0.521 | 0.328 | 0.829 | 0.006 |

|

| |||||

| Disease Free Survival | |||||

| Variable | Comparison group | HazardRatio | HRLowerCL | HRUpperCL | χ2 p-value |

|

| |||||

| 70 and above | 40–49 | 1.612 | 0.685 | 3.793 | 0.274 |

| 60–69 | 40–49 | 1.012 | 0.445 | 2.303 | 0.978 |

| 50–59 | 40–49 | 0.618 | 0.277 | 1.378 | 0.239 |

| N > 0 | N = 0 | 2.458 | 1.362 | 4.438 | 0.003 |

| T 3–4 | T 1–2 | 1.687 | 1.099 | 2.589 | 0.017 |

| Palliative tx | No tx | 0.700 | 0.301 | 1.625 | 0.406 |

| Chemo-XRT | No tx | 0.166 | 0.083 | 0.334 | <0.0001 |

| XRT | No tx | 0.322 | 0.158 | 0.658 | 0.002 |

| tobacco (yes) | tobacco (no) | 1.554 | 0.675 | 3.578 | 0.300 |

| P16unknown | P16− | 0.533 | 0.300 | 0.948 | 0.032 |

| P16+ | P16− | 0.457 | 0.283 | 0.738 | 0.001 |

| B

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Variable | Comparison group | HazardRatio | HRLowerCL | HRUpperCL | χ2 |

| 70 and above | 40–49 | 1.198 | 0.452 | 3.177 | 0.717 |

| 60–69 | 40–49 | 0.984 | 0.396 | 2.446 | 0.972 |

| 50–59 | 40–49 | 0.736 | 0.313 | 1.735 | 0.484 |

| N > 0 | N = 0 | 1.622 | 0.856 | 3.076 | 0.138 |

| T 3–4 | T 1–2 | 2.043 | 1.243 | 3.358 | 0.005 |

| Chemo-XRT | XRT only | 0.529 | 0.283 | 0.991 | 0.047 |

| tobacco (yes) | tobacco (no) | 1.412 | 0.663 | 3.020 | 0.369 |

| Complete tx | Incomplete tx | 0.654 | 0.386 | 1.107 | 0.114 |

| P16unknown | P16− | 0.550 | 0.282 | 1.076 | 0.081 |

| P16+ | P16− | 0.364 | 0.212 | 0.624 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Disease Free Survival | |||||

| Variable | Comparison group | HazardRatio | HRLowerCL | HRUpperCL | χ2 |

|

| |||||

| 70 and above | 40–49 | 0.523 | 0.190 | 1.441 | 0.210 |

| 60–69 | 40–49 | 0.636 | 0.268 | 1.511 | 0.305 |

| 50–59 | 40–49 | 0.589 | 0.261 | 1.333 | 0.204 |

| N > 0 | N = 0 | 1.940 | 0.995 | 3.780 | 0.052 |

| T 3–4 | T 1–2 | 1.184 | 0.716 | 1.958 | 0.511 |

| Chemo-XRT | XRT only | 0.741 | 0.392 | 1.401 | 0.357 |

| tobacco (yes) | tobacco (no) | 1.458 | 0.584 | 3.642 | 0.420 |

| Complete tx | Incomplete tx | 0.482 | 0.283 | 0.818 | 0.007 |

| P16unknown | P16− | 0.249 | 0.109 | 0.567 | 0.001 |

| P16+ | P16− | 0.284 | 0.161 | 0.500 | <0.001 |

Impact of p16 tumor status on survival

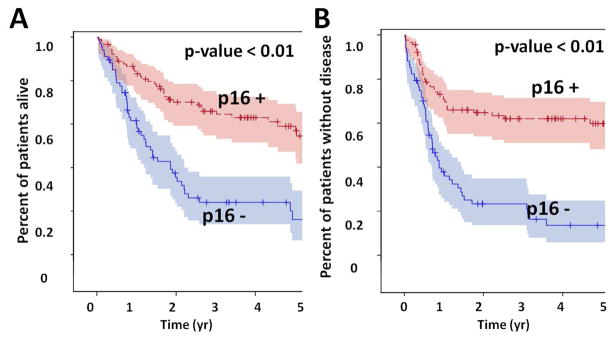

Of the 200 patients in this cohort p16 data was available for 159. Among these patients, 91 were p16 positive (57%) and 68 were p16 negative (43%). Within the entire group, p16 status had a statistically significant impact on overall survival as well as disease free survival (Figure 4). Initial analysis demonstrated that unknown p16 status was in fact protective for survival, likely secondary to the presence of p16+ patients within this cohort. As such, it was included as an additional group in the p16 variable category on final multivariate analysis. A shown in Table 4, p16− patients had significantly worse overall and disease free survival compared to p16+ patients.

Figure 4. p16 effect. All patients with p16 data were analyzed.

P16 positive tumors were associated with significantly improved overall (A) and disease free survival (B).

DISCUSSION

Completion and subsequent analysis of RTOG0129 demonstrated conclusively the existence of multiple OPSCCA patient subsets, likely defined by distinct oncologic drivers (i.e. HPV).(3) Ang and colleagues demonstrated the existence of several OPSCC patient subsets: low risk (HPV+ non smoker), high risk (HPV− smoker) and intermediate risk (HPV+ smoker).(3) The differences in overall and progression free survival were stark: hazard ratios for death and relapse or death were 0.29 and 0.33 respectively for patients in the low risk group compared to the high risk group.(3) The profound effect of HPV on OPSCC outcomes has been confirmed in multiple retrospective single institution and nationwide database analyses.(2–4, 6, 8, 10–13) Together, these data have led to increased optimism regarding the future of clinical outcomes for patients with OPSCCA.

Somewhat lost in the observed improved outcomes for HPV+ OPSCCA is the reality that 25–33% of new OPSCCA diagnoses continue to be related to traditional carcinogens such as alcohol and tobacco.(2) For these patients, survival outcomes have remained stable over the last four decades.(2) The cohort of patients analyzed in the current manuscript highlights some of the challenges associated with OPSCCA driven by traditional carcinogens. By way of comparison with RTOG0129, our patient cohort was approximately 5 years older; the racial breakdown resembled the HPV− arm of RTOG0129 (75% white, 25% black). Smokers constituted 60–70% of the RTOG patients (depending on the arm) but composed over 90% of the veterans we evaluated. Average pack year history of the RTOG0129 HPV+ cohort was 12 pack years while for the HPV− cohort it was 35 pack years. The average pack year history for our cohort was 52.(3) Overall, p16 positive tumors represented only slightly more than half of all analyzed tumors. Although present in a smaller percentage of patients compared to contemporary cohorts, p16 positivity had a significant impact on overall and disease free survival on both univariate and multivariate analysis. That this marked effect is maintained in the presence of an extensive smoking history as that documented in this cohort is somewhat remarkable. Taken together, these data raise interesting questions regarding the precise molecular interaction between tobacco and HPV in this patient population and the primary drivers of carcinogenesis in these tumors.

Veterans with OPSCCA do not present with particularly advanced disease; in fact, all clinical stages are well represented. Despite this, the clinical outcomes for this patient population are dismal. More than 50% of all patients experienced disease progression or recurrence. Among those patients that received curative intent treatment, almost half (47%) experienced disease progression or recurrence. Particularly troubling is the fact that the overwhelming majority of recurrence/progression occurred locoregionally. This poses a significant challenge as we consider means of escalating treatment in order to achieve improved disease control. Chemotherapy has been shown to improve survival by improving locoregional control and decreasing distant metastasis.(14–16) A likely contributor to decreased locoregional and distant control in our patient population is the rate of treatment de-escalation, interruption or early cessation. Approximately 30% of patients were unable to complete the entire curative treatment regimen. One particular concern is the degree to which this patient population requires de-escalation of the chemotherapeutic regimen either through dose reduction, change to less toxic agents (carboplatin) or early cessation of treatment (data not shown). A parallel manuscript demonstrates that tolerance for systemic chemotherapy in our patient population is limited, and additional escalation is unlikely to be tolerable. This represents an unfortunate reality, which has been highlighted by other investigators.(8, 17) In the absence of robust locoregional control, long term survival is severely compromised since salvage options are limited.(18)

An additional difficulty within this patient population is the presence of extensive field cancerization. A substantial proportion of this cohort experienced second primaries in the UAEDT either prior to or following treatment for their OPSCCA. This highlights the importance of traditional carcinogens and also further complicates the therapeutic dilemma. For example, a patient who has been previously treated for laryngeal SCCA using organ preservation modalities is presented with very limited treatment options for a new stage III–IV OPSCCA. We have recently published data from a cohort of veterans with laryngeal cancer and showed that the vast majority of these patients, particularly those with early stage disease are treated with curative intent XRT.(9) Although second primary rates are low among low risk HPV+ OPSCCA patients, smokers with OPSCCA are at increased risk.(19) In our patient population, which reflects the extreme tail of the smoking population at large, field cancerization, manifested through second UAEDT lesion presents a significant clinical concern.

A small portion of our patient cohort was treated with surgery as the primary modality. Since most of these patients received adjuvant XRT or chemo-XRT, we did not conduct a separate survival analysis for this patient group. Surgery has been discussed in the context of both HPV+ and HPV− OPSCCA as means of escalation or de-escalation depending on disease biology.(6, 12, 20–22) There are currently 2 separate clinical trials which address the role of surgical resection in OPSCCA based on HPV status (RTOG Randomized Phase II p16− trial, ECOG 3311 p16+ trial) which should provide us with some guidance as to whether the addition of surgery can successfully improve locoregional control for aggressive OPSCCA. Unfortunately, although surgery might be utilized in select T1–2 OPSCCA tumors to escalate treatment, it is unlikely to address the broader problem of field cancerization.

This is a retrospective analysis that contains several traditional limitations of such studies. Our analysis does not include HPV in situ hybridization data, but rather p16 data which has been used in the past as an adequate surrogate.(3) The patient cohort spans a substantial period of time. Given that the epidemiology of OPSCC has demonstrated a marked shift over the last two decades, it is quite possible that our patient cohort represents a shifting patient population; this may significantly affect the hypothesized interaction between HPV and smoking. Conducting a dynamic analysis on this patient cohort population is not possible due to limited sample size. A parallel project is examining changes in the epidemiology of OPSCC in the national VA cancer database and will provide important additional insight regarding this issue. Despite the limitations of this retrospective analysis we believe that it highlights an important treatment dilemma and identifies a population of patients with OPSCCA which is in dire need of improvements in treatment paradigms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Earlie Thorn RN for her assistance with data collection and her tireless dedication to veterans with head and neck cancer.

Footnotes

Funding sources: Department of Veteran’s Affairs VISN 16 Pilot Project Grant (JPZ). There are no financial disclosures from any authors.

None of the authors have any relationships that they believe could be construed as resulting in an actual, potential, or perceived conflict of interest with regard to the manuscript submitted for review.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlstrom KR, Calzada G, Hanby JD, et al. An evolution in demographics, treatment, and outcomes of oropharyngeal cancer at a major cancer center: a staging system in need of repair. Cancer. 2013;119(1):81–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehanna H, Jones TM, Gregoire V, Ang KK. Oropharyngeal carcinoma related to human papillomavirus. BMJ. 2010;340:c1439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiation therapy, or both. Cancer. 2002;94(11):2967–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pytynia KB, Dahlstrom KR, Sturgis EM. Clinical management of squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: how does this differ for HPV-related tumors? Future Oncol. 2013;9(10):1413–6. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garden AS, Kies MS, Morrison WH, et al. Outcomes and patterns of care of patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma treated in the early 21st century. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudell JJ, Hamilton RD, Otto KJ, Jennelle RL, Pitman KT, Vijayakumar S. Induction Docetaxel, Cisplatin, and 5-Fluorouracil Precludes Definitive Chemoradiotherapy in a Substantial Proportion of Patients With Head and Neck Cancer in a Low Socioeconomic Status Population. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31827a7cff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puthiyaveetil AG, Reilly CM, Pardee TS, Caudell DL. Non-homologous end joining mediated DNA repair is impaired in the NUP98-HOXD13 mouse model for myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2013;37(1):112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews G, Lango M, Cohen R, et al. Nonsurgical management of oropharyngeal, laryngeal, and hypopharyngeal cancer: the Fox Chase Cancer Center experience. Head Neck. 2011;33(10):1433–40. doi: 10.1002/hed.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broglie MA, Soltermann A, Rohrbach D, et al. Impact of p16, p53, smoking, and alcohol on survival in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with primary intensity-modulated chemoradiation. Head Neck. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hed.23231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MA, Weinstein GS, O’Malley BW, Jr, Feldman M, Quon H. Transoral robotic surgery and human papillomavirus status: Oncologic results. Head Neck. 2011;33(4):573–80. doi: 10.1002/hed.21500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granata R, Miceli R, Orlandi E, et al. Tumor stage, human papillomavirus and smoking status affect the survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer: an Italian validation study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1832–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet. 2000;355(9208):949–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Maillard E, Bourhis J. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billan S, Kaidar-Person O, Atrash F, et al. Toxicity of induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for advanced head and neck cancer. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15(5):231–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafereo ME, Hanasono MM, Rosenthal DI, et al. The role of salvage surgery in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5723–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gan SJ, Dahlstrom KR, Peck BW, et al. Incidence and pattern of second primary malignancies in patients with index oropharyngeal cancers versus index nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancers. Cancer. 2013;119(14):2593–601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genden EM, Kotz T, Tong CC, et al. Transoral robotic resection and reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(8):1668–74. doi: 10.1002/lary.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gourin CG, Johnson JT. Surgical treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue. Head Neck. 2001;23(8):653–60. doi: 10.1002/hed.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haughey BH, Hinni ML, Salassa JR, et al. Transoral laser microsurgery as primary treatment for advanced-stage oropharyngeal cancer: a United States multicenter study. Head Neck. 2011;33(12):1683–94. doi: 10.1002/hed.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]