Abstract

The activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines has led to the long-standing belief that these neuronal compartments are the subcellular sites of learning and memory. Of relevance to human health, central neurons in several neuropsychiatric illnesses, including autism related disorders, have atypical numbers and morphologies of dendritic spines. These so-called dendritic spine dysgeneses found in individuals with autism related disorders are consistently replicated in experimental mouse models. Dendritic spine dysgenesis reflects the underlying synaptopathology that drives clinically relevant behavioral deficits in experimental mouse models, providing a platform for testing new therapeutic approaches. By examining molecular signaling pathways, synaptic deficits, and spine dysgenesis in experimental mouse models of autism related disorders we find strong evidence for mTOR to be a critical point of convergence and promising therapeutic target.

Keywords: mTOR, mGluR, TrkB, Fragile X, Rett syndrome, MeCP2, intellectual disability

Introduction

As Santiago Ramón y Cajal began his work describing the fine structure of nervous cells in the late nineteenth century, he noticed that many of the cells "appear bristling with thorns [puntas] or short spines [espinas]" [1], and he envisioned that these protrusions provided a source of functional connectivity between neurons [2, 3]. Though Sherrington provided the concept of the synapse soon thereafter [4], it was not until the development of electron microscopy in the 1950’s and confocal fluorescence microscopy in the 1980’s that spines were confirmed as an important structural component of the synapse. The functional connectivity envisioned by Cajal has been validated and it is now well-established that spines, located on the dendrites of most neurons, are the postsynaptic sites of the majority of excitatory synapses in the brain where they receive input from glutamatergic axons [5]. The ability of the dendrite to add new spines, change spine morphology, and remove spines in response to synaptic activity has led to the wide-held belief that dendritic spines are the center for synaptic plasticity, and therefore a cellular correlate to learning and memory [6]. In support of this view, many neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism with the high comorbidity of intellectual disability (ID) [7–9], present with atypical numbers and structure of dendritic spines, a cellular pathology termed “spine dysgenesis” [10]. We will first briefly describe the development, structure, and function of typical dendritic spines, and progress to detail evidence for spine dysgenesis in autism related disorders (ARDs), tracing the commonalities in dysgenesis from disorders involving entire chromosomes to those caused by single gene mutations.

Dendritic spines: history, functions, structural types, and development

In the developing brain, dendrites first develop devoid of spines and synapses. Dynamic, finger-like protrusions called filopodia begin to project from dendrites during the synaptogenesis period and have the ability to form nascent synapses with nearby axons [11]. Filopodia are highly mobile, extending and retracting to form synapses on the dendritic shaft or on spine-like protrusions that may develop into fully functioning spines [12, 13]. One leading hypothesis is that filopodia recruit axons to form synapses, though the exact mechanism of synaptogenesis during development is still under investigation and may include multiple modalities. As development continues, filopodia give way to dendritic spines, though increased densities of filopodia-like structures are seen in some ARDs, as will be discussed below [14]. Dendritic spines formed during early postnatal life undergo pruning, which eliminates roughly 50% of the synapses/spines [15, 16]. Therefore, the density of dendritic spines is dynamic and determined by neurodevelopmental stage (Figure 1).

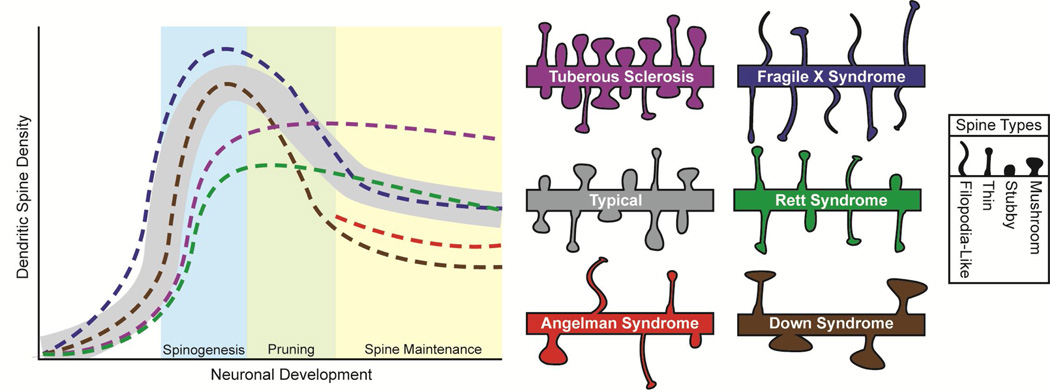

Figure 1. Characterization of dendritic spines in autism related disorders.

Numerical density of dendritic spines during neurodevelopmental stages, and morphologies of mature spines in different ARDs. In typical subjects (grey shading), spines and synapses are formed during early development with the excess or weaker connections being selectively pruned in adolescence, after which spines are maintained during adulthood. Morphological types of spines include thin, mushroom, and stubby, filopodia-like spines are uncommon in the mature brain. Tuberous Sclerosis (purple) has a lower density during spinogenesis, is within typical levels in the pruning stage, and higher densities during maturity with normal morphology. Fragile Xsyndrome (blue) has higher densities until the maintenance stage has been reached, when the density lowers to typical levels and have spines that are morphologically more immature, including a higher proportion of thin and filopodia-like spines. Rett syndrome (green) has a lower density until the maintenance phase with a lower proportion of mushroom spines. There is a lack of density data in Angelman syndrome (red) for both the spinogenesis and pruning stages, but mouse models have lowered densities in the maintenance phase with more variable spine morphology. Down syndrome (brown) has lower densities after the spinogenesis phase with remaining spines having larger heads and longer necks.

Dendritic spines in the mature brain are typically less than 3µm in length, consist of a spherical head (0.5–1.5µm) that serves as a biochemical compartment and is connected to the parent dendrite by a thin neck (<0.5µm in diameter) thought to function as a diffusional barrier for intracellular organelles, as well as signaling ions and molecules. Excitatory synapses form on the head of the spine where the postsynaptic density acts as scaffolding for neurotransmitter receptors and signaling proteins, which includes α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors. The morphology of the spines can vary in overall length, shape of the head, and length of the neck as well as in receptor ratios and diffusional properties. In frozen snapshots of a likely dynamic morphology, three main classes of spines have been described: stubby spines without an obvious neck, mushroom spines with a large head and a thin neck, and thin spines with a small head connected to the dendritic shaft by a long thin neck (Figure 1) [17]. Spine morphology has been demonstrated to contribute or be related to synaptic transmission [18], synapse formation, spine stability [19], and Ca2+ diffusion from the spine head to the parent dendrite [20, 21]. In addition, a positive correlation has been found between spine head size, the ratio of AMPA/NMDA receptors [22], and synaptic strength [23, 24]. These correlations provide strong evidence that the morphology of dendritic spines relates closely to the function of the synapses they belong to.

Even in a mature brain, the structure of spines is plastic and able to change both in size and shape in response to synaptic activity, and these changes can persist for prolonged periods of time. The induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) causes spine enlargement in the hippocampus [25–27] and the cortex [28]. In addition to increasing spine head volume, LTP-inducing stimuli also increase the width of the spine neck and decreases its length [29]. Conversely, the induction of long-term depression (LTD) causes a decrease in spine head volume in the hippocampus [30, 31]. Using two-photon uncaging of glutamate in combination with time-lapse two-photon imaging, Matsuzaki and colleagues showed enlargement of spines in response to induction of LTP, as well as higher levels of AMPA receptors in the postsynaptic density of potentiated spines, and that these changes depend on initial pre-LTP spine morphology. Though transient increases in size were similar in most spines, long-term changes were sustained more often in the smaller spines, leading the authors to interpret that the structure of the smaller spines led to a elevated intrinsic propensity for LTP [32]. These results support previous studies that observed individual spines in vivo over lengthy time spans (weeks to months) and found that smaller spines are particularly more labile [33], while larger spines may be more dominant functionally, but markedly less plastic and may remain morphologically resilient for the animal’s entire adult life [34]. Further work demonstrated that both small and large spines had similar initial increases in [Ca2+]i following stimulation, but larger spines with thicker necks allowed Ca2+ to diffuse to the parent dendrite with less diffusional delay. Ca2+ in smaller spines became trapped in the head, resulting in a prolonged increase in [Ca2+]i localized to the head both in vitro [21] and in vivo [28]. While these studies suggest that morphological differences contribute to a spine’s response to LTP-inducing stimuli through diffusional properties, it should be noted that other groups have found neck diffusion to be greatly influenced by pre- and post-synaptic activity and depolarization [35, 36]. Though the exact relationship between spine morphology and activity-induced plasticity is still under debate, colloquially the larger, more stable, mushroom and stubby spines are referred to as “memory spines” [33], where as thin spines have been dubbed the “learning spines” for their enhanced ability to undergo structural changes [19, 33, 37]. The plastic nature of dendritic spines and the role of spine morphology in synaptic signaling have led to the hypothesis that dendritic spines are a fundamental component of learning and memory.

Spine dysgenesis in autism related disorders

Spine dysgenesis has been described in autopsy brains of several ARDs, their genetic causes ranging from hundreds of affected genes to one, with their pervasiveness relating to both severity and number of clinical symptoms. By examining common clinical phenotypes correlated to spine and synaptic abnormalities between the disorders, we can work to recognize causalities in dysgenesis and identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Down syndrome

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common genetic disorder associated with ID affecting 500,000 Americans. Cognitive defects in those afflicted with DS include delayed speech and language development, and impairments in spatial and long-term memory. Roughly 5–10% of individuals with DS meet the diagnosis criteria for autism spectrum disorder [38–40], though diagnosis can be difficult in patients with severe ID. Most cases of the disorder are caused by a complete trisomy of chromosome 21 (HSA21), though there are rare cases of DS caused by partial trisomies in the long arm of HSA21, deemed the DS critical region (DSCR) [41]. Cognitive development tends to slow in children with DS and the brain undergoes a progressive postnatal degenerative process. Gross neuroanatomical phenotypes associated with DS include slightly reduced brain size and weight at birth, decreased neuronal density, aberrant neuronal morphology, and altered dendritic arborization and spines.

Dysgenesis in dendritic spines of DS patients has been found consistently in the cortex and hippocampus [10, 42–46], with the spines having atypically large heads [42]. With all previous studies having been conducted on brain samples from adults, Takashima and colleagues undertook a large-scale study comparing spine densities from patients collected during different stages of development. They provided evidence that the number of dendritic spines were typical in DS human fetuses, but that after 4 months of age spine number dipped below typical levels in the neocortex [44, 47], and that the remaining spines are morphologically longer than unaffected individuals [46]. These data suggest that dendritic spine dysgenesis in DS results from impaired spine maturation, and that synaptic pruning may be excessive [48].

The sequencing of HSA21 allowed the generation of experimental mouse models to characterize the pathophysiology of DS [49]. Of these models, Ts65Dn is most widely used and consists of a genomic fragment with 49% syntenic regions and 55% of the HSA21 gene orthologs triplicated [50, 51]. These mice have lower dendritic density, enlarged spine heads, as well as impaired hippocampal-dependent learning and memory, tested using the Morris water maze, as well as impaired LTP at excitatory hippocampal synapses [52–55], yet enhanced LTD [56, 57]. Ongoing research in DS has focused on creating mouse models with smaller selections of trisomic genes included in the DS critical region. While these models may not recapitulate all clinical features of DS individuals, they have the potential to identify the pathological role of specific genes. Located in the DSCR, regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1), also known as DSCR1 [58], and Dyrk1a [59] are both implicated in DS spine phenotypes, though we will focus on RCAN1 in this review. Both knockout (KO) [60] and trisomic mouse models of RCAN1 show learning and memory deficits [61] with over-expression resulting in decreased spine density [62]. RCAN1 is a regulator of FMRP [63, 64], a protein that regulates local protein synthesis in dendrites [65–67] and transcriptionally repressed in Fragile Xsyndrome (FXS), a disorder characterized by spine dysgenesis [67–69] which will be discussed in further detail below.

Angelman syndrome

Angelman syndrome (AS) occurs in one out of every 12,000 births and is characterized by ID, speech impairments, ataxia, stereotypical movements, epilepsy and socialization deficits that meet the criteria for autism diagnosis [70]. The vast majority of individuals afflicted with AS have deletions in the long arm of chromosome 15 within the 15q11–13 region encoding for the UBe3a gene [71, 72]. UBe3a is genomically imprinted, causing the paternal allele to be epigenetically silenced selectively in neurons [73–79]. This portion of the genome appears to be especially important in ARDs, as most genetic cases of autism are caused by maternal duplications of 15q11–13 [80–82], paternal deletions cause Prader-Willi syndrome (a disorder with autism comorbidity) [83], and maternal deletions cause AS which has been reported as having a comorbidity as high as ~81% for autism spectrum diagnosis [84].

Of the several mouse models of AS, the best characterized strain is the UBe3a KO generated by including a deletion mutation in exon 2 of the UBE3A gene [85–87]. The maternal deficient heterozygous mice UBE3Am−/p+ recapitulate many AS symptoms including ataxia, motor impairment, hippocampal-dependent learning and memory impairment, and about 20–30% exhibit audiogenic seizures [85, 88–90]. UBE3Am−/p+ mice also display deficiencies in hippocampal LTP [85, 91, 92] and increased metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) dependent LTD [93], which correlate with lower dendritic spine density and shorter spine lengths both in the UBE3Am−/p+ mouse model [89] and an AS individual [94]. A most marked deficit in the UBE3Am−/p+ mice is the impairment in experience-dependent synaptic plasticity, revealed through monocular deprivation studies [90, 95]. These studies led to the hypothesis that the absence of UBE3A leads to the inability to modify or rearrange synapses. Recently, it has been found that UBE3A is a regulator of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (ARC) [96], a protein instrumental in removing AMPA receptors from the postsynaptic density [97], a process required for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity [96]. Abnormal levels of ARC have also been found in Fragile X syndrome (FXS) and Tuberous Sclerosis (TS), and current research is focused on ARC’s role in autism and ID [96, 98].

Rett syndrome

Rett syndrome (RTT) is an X-linked autism spectrum disorder afflicting 1 in 15,000 girls and women and is characterized by typical perinatal development until symptoms develop at 6–18 months of age [99, 100]. These symptoms include motor impairment, stereotypical movements, lack of spoken language, seizures and ID [101]. Eighty percent of RTT individuals carry mutations in MECP2, a gene encoding a global transcriptional regulator that binds to methylated CpG sites in the promoter regions of DNA [102–104]. Brain pathology includes reduced neuronal size but increased cell density in several brain regions [105, 106] as well as reduced dendritic arborization [107] and spine dysgenesis [108–110].

Dendritic spine dysgenesis in individuals with RTT includes not only lower spine density, but also atypical morphology resulting in a decreased proportion of mushroom-type spines in the cortex and hippocampus [107, 109, 110]. Mouse models of RTT are widely used and recapitulate many of the behavioral and anatomical abnormalities associated with the human disorder [111, 112] and additionally show impairments in both LTP and LTD [113, 114]. Commonly used strains of Mecp2 KO mice have impaired dendritic complexity [115, 116] and lower dendritic spine density [117–120] as well as a lack of mushroom spines in cortical and hippocampal neurons [121, 122].

Interestingly, pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus of Mecp2 KO have fewer dendritic spines only before postnatal day 15 [118, 123], suggesting that MeCP2 is necessary for dendritic spine formation during early postnatal development, but a compensatory mechanism takes place after this period in Mecp2 KOs. Potential mechanisms include enhanced hippocampal network activity promoting dendritic spine formation [123], deranged homeostatic plasticity stimulating spinogenesis while affecting pyramidal neuron function [124, 125], or lack of developmental synaptic pruning. Among the many genes regulated by MeCP2, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be the most prominent in RTT spine dysgenesis due to its role in neuronal growth, synapse formation and activity-dependent plasticity through the activation of tropomyosin-related kinase B(TrkB) receptors [100, 126–129] and has been shown to be lowered in RTT [112, 130–132]. Additionally, mutations in MeCP2 lead to lower expression of mGluR [133]. The combination of deficiencies in both TrkB and mGluR signaling in the dendrite may lead to insufficient activity-dependent protein translation, the potential implications of which will be discussed in further detail below.

Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is the most common single-gene cause of autism and ID, afflicting approximately 1 in 4,000 males and 1 in 7,000 females [134]. Those afflicted with FXS have mild-to-severe ID, social anxiety and autistic disorders, increased incidence of epilepsy, attention problems, stereotypical movements, and sensory hypersensitivity [135–138]. The syndrome is typically caused by an expansion of ≥200 CGG-repeats in the FMR1 gene that encodes the Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), which inhibits protein translation through RNA-binding. FMRP is a negative regulator of protein translation [139], many of which are localized to dendrites and dendritic spines [66, 67, 139]. Autopsies of FXS patients have shown atypical spine morphology [140–142], leading to the current hypothesis that FMRP is a key regulator of specific dendritic mRNAs and subsequently controls their translation during growth and plasticity, modulating spine morphology [7].

Reports on dendritic spine density both in human cases and in Fmr1 KO mice are inconsistent, with some studies reporting typical density [141, 143] and others higher density [144–146], though these inconsistencies may arise from the use of animals of different ages, different brain regions, and staining and imaging methods [147]. Interestingly, Nimchinsky and colleagues described that spine density was significantly higher in Fmr1 KO mice at 1 week of age, but this difference did not persist after the 2nd postnatal week [148]. Several live imaging studies provide evidence that the density may be within the typical range in animals older than postnatal-day 7 [149, 150]. If dendritic density is indeed elevated in younger animals, and then returns to levels comparable to those in WT mice, it may suggest that spinogenesis is increased in FXS, with excess spines being properly pruned later in development.

In contrast to the seemingly inconsistent observations on dendritic spine density, a long and tortuous spine morphology is consistently reported and considered the neuropathologic hallmark of FXS [66, 140–146, 148, 151–154]. The types of spines seen in FXS appear similar to filopodia, and many groups have described the spine morphology as ‘immature’ [66, 140–146, 148, 151–155]. In support of the hypothesis that FXS spines may exist in an immature developmentally stalled state well into adulthood, an in vivo 2-photon imaging study demonstrated that dendritic spines in Fmr1 KO mice have a higher turnover rate than those in wild type mice [156]. These atypical features of FXS spines translate to deficits in activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in Fmr1 KO mice. Several studies reported a complete lack of LTP in the neocortex of Fmr1 KO mice, including the visual, prefrontal and somatosensory cortices [149, 157–160]. Mixed reports regarding the state of LTP in the hippocampus can be explained by the induction protocols used: those studies using trains to elicit maximal levels of LTP reported no deficits [157, 161–163], while studies using “threshold” stimulation trains show a deficit in LTP maintenance [164, 165]. On the other hand, Fmr1 KO mice show elevated mGluR-dependent LTD [151, 166, 167], which led to the mGluR theory of Fragile X: the primary defect in FXS is a functional deficiency in circuit plasticity explained by elevated mGluR signaling that influences structural and functional plasticity [168, 169].

Tuberous Sclerosis

Tuberous Sclerosis (TS) is a genetic ARD characterized by the formation of hamartomas in multiple organ systems, and affects 1 in 6,000 individuals [170]. Eighty five percent of those with TS have central nervous system complications including epilepsy, cognitive impairment, and behavioral problems [171]. The comorbidity of autism diagnosis and TS is 29% [172, 173], though more than 50% of TS patients report some autism-like features [174]. TS results from inactivating mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 encoding for either hamartin or tuberin, respectively [175, 176]. These proteins bind together to form a functional heterodimer [177], working in concert as an inhibitor of the small G-protein Rheb, the key activator of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [178–181]. Thus, a mutation in either gene causes the same result: increased activity of mTOR. The discovery that the mTOR pathway is heightened in TS and the tumors TS patients develop led to the implication of the TSC2:TSC1 complex as a tumor suppressor and mTOR as a key player in tumorigenesis [182]. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that this pathway may also be considerably involved in neuronal synaptic plasticity [183–188].

Mouse models of TS have all consistently shown impairments in hippocampal-dependent behavior and synaptic plasticity, such as impaired early-phase LTP [189, 190], and impaired mGluR-dependent LTD [191–194]. Behavioral studies have demonstrated impaired hippocampal-dependent learning in assays such as the Morris water maze, radial maze, and contextual fear conditioning [189, 190, 192, 193, 195–197], as well as impaired social interactions [198]. While these data suggest that dysgenesis of dendritic spines may occur in TS, the study of dendritic spines in TS mouse models has provided somewhat conflicting results. Either Cre-mediated Tsc1 or Tsc2 gene deletion in dissociated neuronal cultures from immature mice (embryonic-day 20 or postnatal-day 3) resulted in fewer dendritic spines, and most of them had an immature filopodia-like morphology [183, 199]. However, dendritic spine density was not affected when Tsc1 was deleted in vivo by virus-induced Cre expression in floxed Tsc1 mice between the 2nd and 3rd postnatal week [192]. Consistently, dendritic spine density and morphology were not affected in 3-week old Tsc2 heterozygous mice, and after conditional deletion of Tsc1 mice, though spine density is higher at 1-month of age [200]. Since overproduced dendritic spines are pruned between the 2nd and 3rd postnatal week of life [201], the seemingly conflicting results above could reflect an initial deficit in spinogenesis followed by impaired spine pruning, which results in higher spine densities in 1-month old mice. In support of potential pharmacological therapies, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin normalizes dendritic spine density in 3-week old Tsc2 heterozygous mice [200]. Rapamycin did not affect dendritic spine density in younger Tsc2 heterozygous mice [199], which further supports the notion intact mTOR signaling is required for dendritic spine maturation after the initial spinogenic period, i.e. during activity-dependent pruning and/or morphological maturation.

mTOR: a convergence point of spine dysgenesis and synaptopathologies in ASD

Dysgenesis of dendritic spines occurs in the majority of individuals afflicted with ARDs, as well as in most experimental mouse models of these syndromes. It would therefore follow that there must be a converging deregulated molecular pathway downstream of the affected genes and upstream of dendritic spine formation and maturation. Identifying this pathway will not only define a causal common denominator in autism-spectrum disorders, but also open new therapeutic opportunities for these devastating conditions.

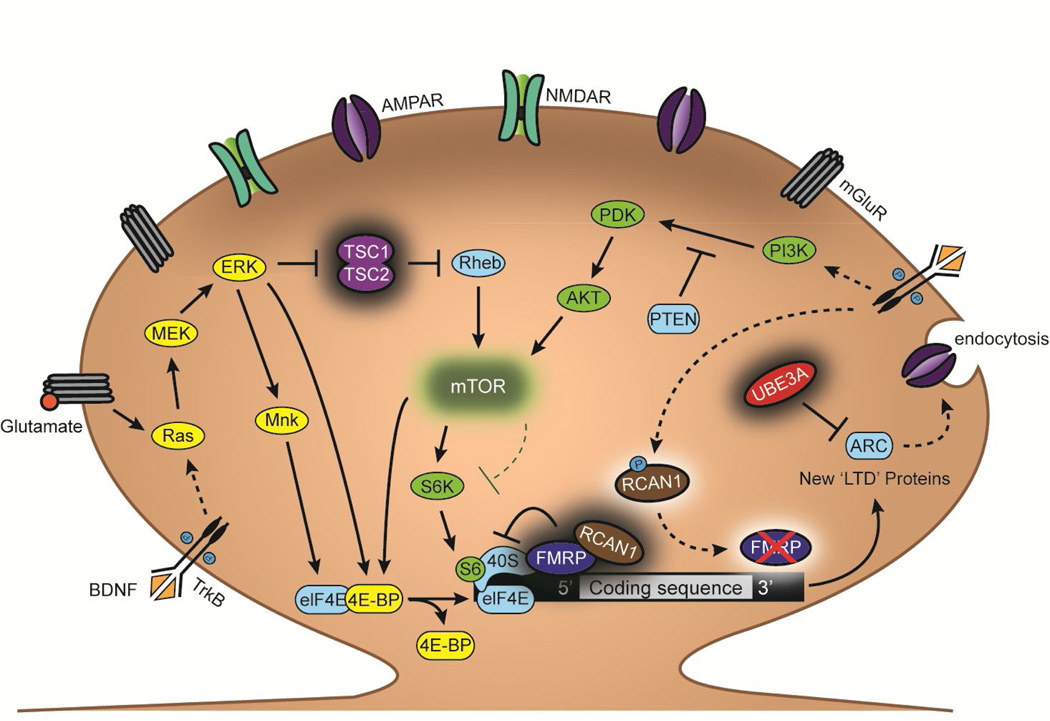

The Ras/ERK and PI3K/mTOR pathways, which regulate protein translation in dendrites near excitatory synapses, have received the most attention as such candidate convergence points [202–205]. Together with the developmental profile of dendritic spine density and similar synaptic plasticity impairments after their experimental manipulation, the roles of Ras/ERK and PI3K/mTOR in all those processes support this hypothesis. The first indications were the realization that FMRP is a repressor of dendritic protein translation, localizes to dendrites near spine synapses, and modulates elements directly downstream of the Ras/ERK and PI3K/mTOR pathways [165]. Extensive work has demonstrated that key components of these signaling pathways are affected in all the ARDs discussed above (Figure 2). For example, RCAN1 (located in the DS critical region) interacts with FMRP, and their deregulation leads to comparable deficits in dendritic protein translation [63, 64]. The TS-affected proteins TSC1 and TSC2 are regulators of Rheb, and loss-of-function mutations in their genes result in higher activity of mTOR. ARC is translated in dendrites through the activation of the Ras/ERK pathway downstream of mGluR, and is the most affected protein by Ube3a deficiency in AS [96], although it is also deregulated in FXS [206] and TS [207]. The levels of mGluR and BDNF are lower in mouse models of RTT [130–132, 208, 209], which are upstream in both the Ras/ERK [210] and PI3K/mTOR pathways [211], and result in lower levels of the serine/threonine kinase Akt and mTOR in MeCP2-deficient mice [212]. Phosphatase and tens in homolog (PTEN), a protein often mutated in autistic patients [213–218], inhibits the activation of PDK by PI3K [219, 220].

Figure 2. Pathways involved in the translational regulation of “LTD proteins”.

ARDs share molecular pathologies affecting a common signaling pathway involved in activity-dependent protein synthesis in distal dendrites near spine synapses. The Ras/ERK and PI3K/mTOR signaling pathways couple synaptic activation of mGluR and the BDNF TrkB receptors to protein translation that is essential to the maintenance of LTD. Mutations in several regulators of these pathways, including the genes encoding the proteins TSC1/2, FMRP, DSCR1, UBE3A, and PTEN are responsible for ARDs. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the nuclear protein MeCP2, which causes RTT, result in lower levels of mGluR and BDNF, lowering the activation of those signaling pathways in response to glutamatergic synaptic activity and activity-dependent BDNF release. While mTOR is typically an activator of protein translation through 4E-BP and S6K, pathological increases in mTOR levels repress translation of LTD-specific proteins, though the exact mechanism(s) is unknown. Selective inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin alleviates autism-related deficits in FXS and TS, providing evidence that this pathway is causal in the pathological mechanisms leading to autism.

Abbreviations: Glu: glutamate; Ras: rat sarcoma proto-oncogenic G-protein; MEK: MAPK kinase; ERK: extracellular signal-related kinase; Rheb: RAS homolog enriched in brain; Mnk: MAP kinases phosphorylate; elF4E: Eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; 4E-BP: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein; S6: ribosomal protein S6; S6K: S6 kinase; 40S: eukaryotic small ribosomal subunit; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PDK: phosphoinositide-dependent kinase; P: phosphate.

Though many of the discussed ARDs affect multiple signaling pathways, the significant overlap on mTOR strongly suggests it is a critical convergence point. While mTOR activity usually increases dendritic protein translation, heightened mTOR activity in TS inhibits the synthesis of proteins necessary for stabilization of mGluR-dependent LTD [191]. These data, together with previous reports of lower mTOR levels resulting in reduced protein translation, suggest that mTOR activity levels need to be within a proper range to support activity-dependent synaptic plasticity [221]. Intriguingly, those ARDs with impaired mTOR-dependent translation (TS and RTT) show impaired LTD, whereas those with heightened dendritic protein translation (DS, AS and FXS) display elevated LTD [56, 63, 222, 223]. In addition, there is a correlation between the magnitude of dendritic spine pruning, LTD, and dendritic protein translation: ARDs with excessive pruning (DS, FXS and perhaps AS) show heightened dendritic protein translation and LTD, whereas those with impaired pruning display lower protein translation and LTD (TS and RTT). Indeed, LTD in the hippocampus leads to dendritic spine shrinkage and subsequent spine synapse pruning [30, 31, 224, 225], and deficiencies in mGluR-LTD disrupt the elimination of spine synapses in the cerebellum [226]. Though there are many factors and pathways involved in the pruning of dendritic spines and their excitatory synapses, these correlations suggest that mTOR is a potential site of therapeutic intervention for autism-related disorders. In support of this notion, studies in both FXS and TS show alleviation of both synaptic and behavioral phenotypes after treatment of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin [227, 228]. It is tempting to speculate that similar treatments will be effective to alleviate synaptopathologies and autistic behaviors in other ARDs.

Conclusion

Cajal once postulated, "the future will prove the great physiological role played by the dendritic spines” [229]. And indeed, it is now widely accepted that dendritic spines are the site of neuronal plasticity of excitatory synapses and the focal point for synaptopathophysiologies of ARDs. Individuals and mouse models of ARDs all display spine dysgenesis, with mTOR-regulated protein translation being a critical point of convergence. Deviations from optimal levels of protein synthesis correlate with the magnitude of dendritic spine pruning and LTD in ARDs. Alleviation of heightened mTOR activity rescues both synaptic and behavioral phenotypes in FXS and TS animals. Correcting mTOR signaling levels also reversed ARD phenotypes in adult fully symptomatic mice, challenging the traditional view that genetic defects caused irreversible developmental defects [230]. More excitingly, these observations demonstrate the potential of pharmacological therapies for neurodevelopmental disorders. The list of ARDs that have been reversed in adult symptomatic mice continues to grow, and also includes RTT [231], DS [232, 233], and AS [92]. Together, these findings demonstrate the remarkable plastic nature of the brain and imply that if the causal denominator of ARDs could be found and therapeutically targeted, we may be able to allow the ARD brain to rewire itself and relieve clinical symptoms once believed to be irreversible. The analysis of correlative physiological and behavioral phenotypes and identification of the common mTOR pathway will hopefully provide such potential targets.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH grants NS-065027 and NS-40593 (to LP-M). We thank Drs. Xin Xu, Eric Miller, and Wei Li for thoughtful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors do not have competing financial interests

References

- 1.Ramon Y Cajal S. Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves. [accessed September 18, 2014];Rev. Tri. Hist. Norm. Pat. 1888 :1–10. http://www.thescientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/37954/title/The-Neuron-Doctrine--circa-1894/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramón y Cajal S. Significación fisiológica de las expansiones protoplásmicas y nerviosas de la sustancia gris. Rev. Cienc. Med. Barc. 1891;22:23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramón y Cajal S. La fine structure des centres nerveaux. the Croonian Lecture. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1894;55:443–468. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherrington CS, Laslett EE. Observations on some spinal reflexes and the interconnection of spinal segments. [accessed September 22, 2014];J. Physiol. 1903 29:58–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1903.sp000946. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1540608&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt DH, Zhang S, Gan W-B. Dendritic spine dynamics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009;71:261–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuste R, Bonhoeffer T. Morphological changes in dendrritic spines associated with long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001:1071–1089. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dierssen M, Ramakers GJA. Dendritic pathology in mental retardation: from molecular genetics to neurobiology. Genes. Brain. Behav. 2006;5(Suppl 2):48–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufmann WE, Moser HW. Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb. Cortex. 2000;10:981–991. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.981. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11007549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penzes P, Cahill ME, a Jones K, VanLeeuwen J-E, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purpura DP. Spine “Dysgenesis” and Mental Retardation. Science (80-. ) 1974;186:1126–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4169.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziv NE, Smith SJ. Evidence for a Role of Dendritic Filopodia in Synaptogenesis and Spine Formation. Neuron. 1996;17:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dailey ME, Smith SJ. The Dynamics of Dendritic Structure in Developing Hippocampal Slices. J. Neurosci. 1996;76:2983–2994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-02983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiala JC, Feinberg M, Popov V, Harris KM. Synaptogenesis Via Dendritic Filopodia in Developing Hippocampal Area CA1. [accessed September 15, 2014];J. Neurosci. 1998 18:8900–8911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08900.1998. http://www.jneurosci.org/content/18/21/8900.long. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuo Y, Lin A, Chang P, Gan W-B. Development of long-term dendritic spine stability in diverse regions of cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2005;46:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Felipe J, Marco P, a Fairén, Jones EG. Inhibitory synaptogenesis in mouse somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1997;7:619–634. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.7.619. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9373018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huttenlocher PR. Morphometric study of human cerebral cortex development. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:517–527. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90031-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters A, Kaiserman-Abramof IR. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex. The perikaryon, dendrites and spines. Am. J. Anat. 1970;127:321–355. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001270402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GCR, Nemoto T, Miyashita Y, Iino M, Kasai H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtmaat AJGD, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, et al. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korkotian E, Holcman D, Segal M. Dynamic regulation of spine-dendrite coupling in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:2649–2663. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguchi J, Masanori M, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Spine-neck geometry determines NMDA receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling in dendrites. Neuron. 2005;46:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takumi Y, Ramírez-León V, Laake P, Rinvik E, Ottersen OP. Different modes of expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors in hippocampal synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:618–624. doi: 10.1038/10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levenga J, Willemsen R. Perturbation of dendritic protrusions in intellectual disability. Prog. Brain Res. 2012;197:153–168. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-54299-1.00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KFH, Soares C, Béïque J-C. Examining form and function of dendritic spines. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/704103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Harreveld A, Fifkova E. Swelling of dendritic spines in the fascia dentata after stimulation of the perforant fibers as a mechanism of post-tetanic potentiation. Exp. Neurol. 1975;49:736–749. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fifková E, Van Harreveld A. Long-lasting morphological changes in dendritic spines of dentate granular cells following stimulation of the entorhinal area. J. Neurocytol. 1977;6:211–230. doi: 10.1007/BF01261506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park M, Salgado JM, Ostroff L, Helton TD, Robinson CG, Harris KM, et al. Plasticity-induced growth of dendritic spines by exocytic trafficking from recycling endosomes. Neuron. 2006;52:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noguchi J, Nagaoka A, Watanabe S, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kitamura K, Kano M, et al. In vivo two-photon uncaging of glutamate revealing the structure-function relationships of dendritic spines in the neocortex of adult mice. J. Physiol. 2011;589:2447–2457. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.207100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fifková E, Anderson CL. Stimulation-induced changes in dimensions of stalks of dendritic spines in the dentate molecular layer. Exp. Neurol. 1981;74:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamoto K-I, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Hayashi Y. Rapid and persistent modulation of actin dynamics regulates postsynaptic reorganization underlying bidirectional plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1104–1112. doi: 10.1038/nn1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Q, Homma KJ, Poo M. Shrinkage of dendritic spines associated with long-term depression of hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2004;44:749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trachtenberg JT, Chen BE, Knott GW, Feng G, Sanes JR, Welker E, et al. Long-term in vivo imaging of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in adult cortex. Nature. 2002;420:788–794. doi: 10.1038/nature01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grutzendler J, Kasthuri N, Gan W-B. Long-term dendritic spine stability in the adult cortex. Nature. 2002;420:812–816. doi: 10.1038/nature01276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunditz A, Holbro N, Tian L, Zuo Y, Oertner TG. Spine neck plasticity controls postsynaptic calcium signals through electrical compartmentalization. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13457–13466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2702-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Neuronal activity regulates diffusion across the neck of dendritic spines. Science. 2005;310:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1114816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasai H, Matsuzaki M, Noguchi J, Yasumatsu N, Nakahara H. Structure-stability-function relationships of dendritic spines. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:360–368. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghaziuddin M, Tsai L, Ghaziuddin N. Autism in Down’s syndrome: presentation and diagnosis. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1992;36:449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1992.tb00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kent L, Evans J, Paul M, Sharp M. Comorbidity of autistic spectrum disorders in children with Down syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1999;41:153–158. doi: 10.1017/s001216229900033x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10210247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.York A, von Fraunhofer N, Turk J, Sedgwick P. Fragile-X syndrome, Down’s syndrome and autism: awareness and knowledge amongst special educators. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1999;43:314–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonarakis SE, Lyle R, Dermitzakis ET, Reymond A, Deutsch S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: from genomics to pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nrg1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin-Padilla M. Pyramidal cell abnormalities in the motor cortex of a child with Down’s syndrome. A Golgi study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1976;167:63–81. doi: 10.1002/cne.901670105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suetsugu M, Mehraein P. Spine distribution along the apical dendrites of the pyramidal neurons in Down’s syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;50:207–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00688755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takashima S, Becker LE, Armstrong DL, Chan F. Abnormal neuronal development in the visual cortex of the human fetus and infant with down’s syndrome. A quantitative and qualitative golgi study. Brain Res. 1981;225:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrer I, Gullotta F. Down’s syndrome and Alzheimer's disease: dendritic spine counts in the hippocampus. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;79:680–685. doi: 10.1007/BF00294247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takashima S, Iida K, Mito T, Arima M. Dendritic and histochemical development and ageing in patients with Down’s syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1994 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1994.tb00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takashima S, Ieshima A, Nakamura H, Becker LE. Dendrites, dementia and the down syndrome. Brain Dev. 1989;11:131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(89)80082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benavides-Piccione R, Ballesteros-Yáñez I, de Lagrán MM, Elston G, Estivill X, Fillat C, et al. On dendrites in Down syndrome and DS murine models: a spiny way to learn. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004;74:111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu C, Belichenko PV, Zhang L, Fu D, Kleschevnikov AM, Baldini A, et al. Mouse models for Down syndrome-associated developmental cognitive disabilities. Dev. Neurosci. 2011;33:404–413. doi: 10.1159/000329422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davisson MT, Schmidt C, Akeson EC. Segmental trisomy of murine chromosome 16: a new model system for studying Down syndrome. [accessed September 17, 2014];Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1990 360:263–280. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/2147289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reeves RH, Irving NG, Moran TH, Wohn A, Kitt C, Sisodia SS, et al. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhbits learning and behavior deficits. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:177–184. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleschevnikov AM, Belichenko PV, Villar AJ, Epstein CJ, Malenka RC, Mobley WC. Hippocampal long-term potentiation suppressed by increased inhibition in the Ts65Dn mouse, a genetic model of Down syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8153–8160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belichenko PV, Kleschevnikov AM, Salehi A, Epstein CJ, Mobley WC. Synaptic and cognitive abnormalities in mouse models of Down syndrome: exploring genotype-phenotype relationships. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;504:329–345. doi: 10.1002/cne.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belichenko NP, Belichenko PV, Kleschevnikov AM, Salehi A, Reeves RH, Mobley WC. The “Down syndrome critical region” is sufficient in the mouse model to confer behavioral, neurophysiological, and synaptic phenotypes characteristic of Down syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:5938–5948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1547-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Popov VI, Kleschevnikov AM, Klimenko OA, Stewart MG, Belichenko PV. Three-dimensional synaptic ultrastructure in the dentate gyrus and hippocampal area CA3 in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011;519:1338–1354. doi: 10.1002/cne.22573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siarey RJ, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, a Balbo, Rapoport SI, Galdzicki Z. Increased synaptic depression in the Ts65Dn mouse, a model for mental retardation in Down syndrome. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1917–1920. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00083-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10608287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott-McKean JJ, Costa ACS. Exaggerated NMDA mediated LTD in a mouse model of Down syndrome and pharmacological rescuing by memantine. Learn. Mem. 2011;18:774–778. doi: 10.1101/lm.024182.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies KJA, Ermak G, Rothermel BA, Pritchard M, Heitman J, Ahnn J, et al. Renaming the DSCR1/Adapt78 gene family as RCAN: regulators of calcineurin. FASEB J. 2007;21:3023–3028. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7246com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomazeau A, Lassalle O, Iafrati J, Souchet B, Guedj F, Janel N, et al. Prefrontal deficits in a murine model overexpressing the down syndrome candidate gene dyrk1a. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:1138–1147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2852-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoeffer CA, Dey A, Sachan N, Wong H, Patterson RJ, Shelton JM, et al. The Down syndrome critical region protein RCAN1 regulates long-term potentiation and memory via inhibition of phosphatase signaling. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:13161–13172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3974-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dierssen M, Arqué G, McDonald J, Andreu N, Martínez-Cué C, Flórez J, et al. Behavioral characterization of a mouse model overexpressing DSCR1/RCAN1. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin KR, Corlett A, Dubach D, Mustafa T, Coleman HA, Parkington HC, et al. Over-expression of RCAN1 causes Down syndrome-like hippocampal deficits that alter learning and memory. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3025–3041. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang W, Zhu JZ, Chang KT, Min K-T. DSCR1 interacts with FMRP and is required for spine morphogenesis and local protein synthesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3655–3666. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang KT, Ro H, Wang W, Min K-T. Meeting at the crossroads: common mechanisms in Fragile X and Down Syndrome. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weiler IJ, Irwin SA, Klintsova AY, Spencer CM, Brazelton AD, Miyashiro K, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein is translated near synapses in response to neurotransmitter activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:5395–5400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Irwin SA, Galvez R, Greenough WT. Dendritic Spine Structural Anomalies in Fragile-X Mental Retardation Syndrome. Cereb. Cortex. 2000;10:1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waung MW, Huber KM. Protein translation in synaptic plasticity: mGluR-LTD, Fragile X. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009;19:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bagni C, Greenough WT. From mRNP trafficking to spine dysmorphogenesis: the roots of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:376–387. doi: 10.1038/nrn1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clayton-Smith J. Angelman syndrome: a review of the clinical and genetic aspects. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:87–95. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.2.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaplan LC, Wharton R, Elias E, Mandell F, Donlon T, Latt SA. Clinical heterogeneity associated with deletions in the long arm of chromosome 15: report of 3 new cases and their possible genetic significance. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1987;28:45–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320280107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams CA, Driscoll DJ, Dagli AI. Clinical and genetic aspects of Angelman syndrome. Genet. Med. 2010;12:385–395. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181def138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Albrecht U, Sutcliffe JS, Cattanach BM, Beechey CV, Armstrong D, Eichele G, et al. Imprinted expression of the murine Angelman syndrome gene, Ube3a, in hippocampal and Purkinje neurons. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:75–78. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang Y-H, Tsai T-F, Bressler J, Beaudet AL. Imprinting in Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1998;8:334–342. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rougeulle C, Cardoso C, Fontés M, Colleaux L, Lalande M. An imprinted antisense RNA overlaps UBE3A and a second maternally expressed transcript. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:15–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Runte M, Huttenhofer A, Gross S, Kiefmann M, Horsthemke B, Buiting K. The IC-SNURF-SNRPN transcript serves as a host for multiple small nucleolar RNA species and as an antisense RNA for UBE3A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2687–2700. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamasaki K. Neurons but not glial cells show reciprocal imprinting of sense and antisense transcripts of Ube3a. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:837–847. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Runte M, Kroisel PM, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Varon R, Horn D, Cohen MY, et al. SNURF-SNRPN and UBE3A transcript levels in patients with Angelman syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2004;114:553–561. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1104-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Landers M, Bancescu DL, Le Meur E, Rougeulle C, Glatt-Deeley H, Brannan C, et al. Regulation of the large (approximately 1000 kb) imprinted murine Ube3a antisense transcript by alternative exons upstream of Snurf/Snrpn. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3480–3492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Browne CE, Dennis NR, Maher E, Long FL, Nicholson JC, Sillibourne J, et al. Inherited interstitial duplications of proximal 15q: genotype-phenotype correlations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:1342–1352. doi: 10.1086/301624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cook EH, Lindgren V, Leventhal BL, Courchesne R, Lincoln A, Shulman C, et al. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. [accessed September 17, 2014];Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997 60:928–934. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1712464&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mao R, Jalal SM, Snow K, Michels VV, Szabo SM, Babovic-Vuksanovic D. Characteristics of two cases with dup(15) (q 11.2-q 12): one of maternal and one of paternal origin. Genet. Med. 2000;2:131–135. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dykens EM, Lee E, Roof E. Prader-Willi syndrome and autism spectrum disorders: an evolving story. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2011;3:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trillingsgaard A, ØStergaard JR. Autism in Angelman syndrome: an exploration of comorbidity. Autism. 2004;8:163–174. doi: 10.1177/1362361304042720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiang Y-H, Armstrong D, Albrecht U, Atkins C, Sweatt JD, Beaudet AL. Mutation of the Angelman Ubiquitin Ligase in Mice Causes Increased Cytoplasmic p53 and Deficits of Contextual Learning and Long-Term Potentiation. Neuron. 1998;21:799–811. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mabb AM, Judson MC, Zylka MJ, Philpot BD. Angelman Syndrome: Insights into Genomic Imprinting and Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jana NR. Understanding the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome through animal models. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:710943. doi: 10.1155/2012/710943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miura K, Kishino T, Li E, Webber H, Dikkes P, Holmes GL, et al. Neurobehavioral and electroencephalographic abnormalities in Ube3a maternal-deficient mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:149–159. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dindot SV, Antalffy BA, Bhattacharjee MB, Beaudet AL. The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:111–118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yashiro K, Riday TT, Condon KH, Roberts AC, Bernardo DR, Prakash R, et al. Ube3a is required for experience-dependent maturation of the neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:777–783. doi: 10.1038/nn.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weeber EJ, Jiang Y-H, Elgersma Y, Varga AW, Carrasquillo Y, Brown SE, et al. Derangements of Hippocampal Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II in a Mouse Model for Angelman Mental Retardation Syndrome. [accessed September 18, 2014];J. Neurosci. 2003 23:2634–2644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02634.2003. http://www.jneurosci.org/content/23/7/2634.long. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van Woerden GM, Harris KD, Hojjati MR, Gustin RM, Qiu S, de Avila Freire R, et al. Rescue of neurological deficits in a mouse model for Angelman syndrome by reduction of alphaCaMKII inhibitory phosphorylation. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:280–282. doi: 10.1038/nn1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pignatelli M, Piccinin S, Molinaro G, Di Menna L, Riozzi B, Cannella M, et al. Changes in mGlu5 receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity and coupling to homer proteins in the hippocampus of Ube3A hemizygous mice modeling angelman syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:4558–4566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1846-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jay V, Becker LE, Chan F-W, Perry TL. Puppet-like syndrome of Angelman: A pathologic and neurochemical study. Neurology. 1991;41:416–416. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sato M, Stryker MP. Genomic imprinting of experience-dependent cortical plasticity by the ubiquitin ligase gene Ube3a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:5611–5616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001281107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Greer PL, Hanayama R, Bloodgood BL, Mardinly AR, Lipton DM, Flavell SW, et al. The Angelman Syndrome protein Ube3A regulates synapse development by ubiquitinating arc. Cell. 2010;140:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shepherd JD, Bear MF. New views of Arc, a master regulator of synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KYS, Mele A, Fraser CE, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Neul JL, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome: a prototypical neurodevelopmental disorder. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:118–128. doi: 10.1177/1073858403260995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chapleau C, Larimore JL, Theibert A, Pozzo-Miller L. Modulation of dendritic spine development and plasticity by BDNF and vesicular trafficking: fundamental roles in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with mental retardation and autism. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2009;1:185–196. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Percy AK, Lane JB. Rett syndrome: clinical and molecular update. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2004;16:670–677. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000143693.59408.ce. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15548931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bauman ML, Kemper TL, Arin DM. Pervasive neuroanatomic abnormalities of the brain in three cases of Rett ’ s syndrome. Neurology. 1995;45:1581–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bauman ML, Kemper TL, Arin DM. Microscopic observations of the brain in Rett syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:105–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Armstrong D, Dunn JK, Antalffy B, Trivedi R. Selective Dendritic Alterations in the Cortex of Rett Syndrome. [accessed September 18, 2014];J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1995 54:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199503000-00006. http://journals.lww.com/jneuropath/Abstract/1995/03000/Selective_Dendritic_Alterations_in_the_Cortex_of.6.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kaufmann WE, Taylor CV, Hohmann CF, Sanwal IB, Naidu S. Abnormalities in neuronal maturation in Rett syndrome neocortex: preliminary molecular correlates. [accessed September 18, 2014];Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 6 Suppl. 1997 1:75–77. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/9452926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Belichenko PV, Oldfors A, Hagberg B, Dahlström A. Rett syndrome: 3-D confocal microscopy of cortical pyramidal dendrites and afferents. [accessed September 18, 2014];Neuroreport. 1994 5:1509–1513. http://journals.lww.com/neuroreport/Abstract/1994/07000/Rett_syndrome__3_D_confocal_microscopy_of_cortical.25.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chapleau C, Calfa GD, Lane MC, Albertson AJ, Larimore JL, Kudo S, et al. Dendritic spine pathologies in hippocampal pyramidal neurons from Rett syndrome brain and after expression of Rett-associated MECP2 mutations. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;35:219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li W, Pozzo-Miller L. Beyond Widespread Mecp2 Deletions to Model Rett Syndrome: Conditional Spatio-Temporal Knockout, Single-Point Mutations and Transgenic Rescue Mice. Autism Open Access. 2012;2012:1–20. doi: 10.4172/2165-7890.S1-005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu X, Miller EC, Pozzo-Miller L. Dendritic spine dysgenesis in Rett syndrome. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Moretti P, Levenson JM, Battaglia F, Atkinson R, Teague R, Antalffy B, et al. Learning and memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:319–327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Asaka Y, Jugloff DGM, Zhang L, Eubanks JH, Fitzsimonds RM. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity is impaired in the Mecp2-null mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;21:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fukuda T, Itoh M, Ichikawa T, Washiyama K, Goto Y. Delayed maturation of neuronal architecture and synaptogenesis in cerebral cortex of Mecp2-deficient mice. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005;64:537–544. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.537. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15977646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nguyen MVC, Du F, Felice CA, Shan X, Nigam A, Mandel G, et al. MeCP2 is critical for maintaining mature neuronal networks and global brain anatomy during late stages of postnatal brain development and in the mature adult brain. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:10021–10034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1316-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tropea D, Giacometti E, Wilson NR, Beard C, McCurry C, Fu DD, et al. Partial reversal of Rett Syndrome-like symptoms in MeCP2 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:2029–2034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812394106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chapleau C, Boggio EM, Calfa G, Percy AK, Giustetto M, Pozzo-Miller L. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of Mecp2 mutant mice show a dendritic spine phenotype only in the presymptomatic stage. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:976164. doi: 10.1155/2012/976164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Landi S, Putignano E, Boggio EM, Giustetto M, Pizzorusso T, Ratto GM. The short-time structural plasticity of dendritic spines is altered in a model of Rett syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:45. doi: 10.1038/srep00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Castro J, Garcia RI, Kwok S, Banerjee A, Petravicz J, Woodson J, et al. Functional recovery with recombinant human IGF1 treatment in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:9941–9946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311685111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chao H-T, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Baj G, Patrizio A, Montalbano A, Sciancalepore M, Tongiorgi E. Developmental and maintenance defects in Rett syndrome neurons identified by a new mouse staging system in vitro. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:18. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Calfa G, Percy AK, Pozzo-Miller L. Experimental models of Rett syndrome based on Mecp2 dysfunction. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2011;236:3–19. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Blackman MP, Djukic B, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. A critical and cellautonomous role for MeCP2 in synaptic scaling up. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:13529–13536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3077-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Qiu Z, Sylwestrak EL, Lieberman DN, Zhang Y, Liu X-Y, Ghosh A. The Rett syndrome protein MeCP2 regulates synaptic scaling. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:989–994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0175-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Poo MM. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ohira K, Hayashi M. A new aspect of the TrkB signaling pathway in neural plasticity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:276–285. doi: 10.2174/157015909790031210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chapleau C, Pozzo-Miller L. Divergent roles of p75NTR and Trk receptors in BDNF’s effects on dendritic spine density and morphology. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:578057. doi: 10.1155/2012/578057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Panja D, Bramham CR. BDNF mechanisms in late LTP formation: A synthesis and breakdown. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt C):664–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chang Q, Khare G, Dani V, Nelson S, Jaenisch R. The disease progression of Mecp2 mutant mice is affected by the level of BDNF expression. Neuron. 2006;49:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang H, Chan S, Ogier M, Hellard D, Wang Q, Smith C, et al. Dysregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and neurosecretory function in Mecp2 null mice. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10911–10915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1810-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Li W, Calfa G, Larimore J, Pozzo-Miller L. Activity-dependent BDNF release and TRPC signaling is impaired in hippocampal neurons of Mecp2 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:17087–17092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205271109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhong X, Li H, Chang Q. MeCP2 phosphorylation is required for modulating synaptic scaling through mGluR5. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:12841–12847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2784-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Willemsen R, Levenga J, Oostra BA. CGG repeat in the FMR1 gene: size matters. Clin. Genet. 2011;80:214–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sabaratnam M, Vroegop PG, Gangadharan SK. Epilepsy and EEG findings in 18 males with fragile X syndrome. Seizure. 2001;10:60–63. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Berry-Kravis E. Epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007;44:724–728. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hagerman R, Berry-Kravis E, Kaufmann WE, Ono MY, Tartaglia N, Lachiewicz A, et al. Advances in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:378–390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hagerman P, Stafstrom CE. Origins of epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Epilepsy Curr. 2009;9:108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2009.01309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Santoro MR, Bray SM, Warren ST. Molecular mechanisms of fragile X syndrome: a twenty-year perspective. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2012;7:219–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rudelli RD, Brown WT, Wisniewski K, Jenkins EC, Laure-Kamionowska M, Connell F, et al. Adult fragile X syndrome. Clinico-neuropathologic findings. [accessed September 19, 2014];Acta Neuropathol. 1985 67:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00687814. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hinton VJ, Brown WT, Wisniewski K, Rudelli RD. Analysis of neocortex in three males with the fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1991;41:289–294. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Irwin SA, Patel B, Idupulapati M, Harris JB, Crisostomo RA, Larsen BP, et al. Abnormal dendritic spine characteristics in the temporal and visual cortices of patients with fragile-X syndrome: a quantitative examination. [accessed September 03, 2014];Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001 98:161–167. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010115)98:2<161::aid-ajmg1025>3.0.co;2-b. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11223852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Irwin SA, Idupulapati M, Gilbert ME, Harris JB, Chakravarti AB, Rogers EJ, et al. Dendritic spine and dendritic field characteristics of layer V pyramidal neurons in the visual cortex of fragile-X knockout mice. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;111:140–146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Comery TA, Harris JB, Willems PJ, Oostra BA, Irwin SA, Weiler IJ, et al. Abnormal dendritic spines in fragile X knockout mice: Maturation and pruning deficits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:5401–5404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Galvez R, Greenough WT. Sequence of abnormal dendritic spine development in primary somatosensory cortex of a mouse model of the fragile X mental retardation syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;135:155–160. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.McKinney BC, Grossman AW, Elisseou NM, Greenough WT. Dendritic spine abnormalities in the occipital cortex of C57BL/6 Fmr1 knockout mice. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005;136B:98–102. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Portera-Cailliau C. Which comes first in fragile X syndrome, dendritic spine dysgenesis or defects in circuit plasticity? Neuroscientist. 2012;18:28–44. doi: 10.1177/1073858410395322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Nimchinsky EA, Oberlander AM, Svoboda K. Abnormal development of dendritic spines in FMR1 knock-out mice. [accessed September 19, 2014];J. Neurosci. 2001 21:5139–5146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05139.2001. http://www.jneurosci.org/content/21/14/5139.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Meredith RM, Holmgren CD, Weidum M, Burnashev N, Mansvelder HD. Increased threshold for spike-timing-dependent plasticity is caused by unreliable calcium signaling in mice lacking fragile X gene FMR1. Neuron. 2007;54:627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Cruz-Martín A, Crespo M, Portera-Cailliau C. Delayed stabilization of dendritic spines in fragile X mice. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:7793–7803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0577-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Koekkoek SKE, Yamaguchi K, Milojkovic BA, Dortland BR, Ruigrok TJH, Maex R, et al. Deletion of FMR1 in Purkinje cells enhances parallel fiber LTD, enlarges spines, and attenuates cerebellar eyelid conditioning in Fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2005;47:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Restivo L, Ferrari F, Passino E, Sgobio C, Bock J, Oostra BA, et al. Enriched environment promotes behavioral and morphological recovery in a mouse model for the fragile X syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:11557–11562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Antar LN, Li C, Zhang H, Carroll RC, Bassell GJ. Local functions for FMRP in axon growth cone motility and activity-dependent regulation of filopodia and spine synapses. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006;32:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bilousova TV, Dansie L, Ngo M, Aye J, Charles JR, Ethell DW, et al. Minocycline promotes dendritic spine maturation and improves behavioural performance in the fragile X mouse model. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46:94–102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.061796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Pop AS, Levenga J, de Esch CEF, Buijsen RAM, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Li T, et al. Rescue of dendritic spine phenotype in Fmr1 KO mice with the mGluR5 antagonist AFQ056/Mavoglurant. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:1227–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Pan F, Aldridge GM, Greenough WT, Gan W-B. Dendritic spine instability and insensitivity to modulation by sensory experience in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:17768–17773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Li J, Pelletier MR, Perez Velazquez J-L, Carlen PL. Reduced cortical synaptic plasticity and GluR1 expression associated with fragile X mental retardation protein deficiency. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;19:138–151. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Zhao M-G, Toyoda H, Ko SW, Ding H-K, Wu L-J, Zhuo M. Deficits in trace fear memory and long-term potentiation in a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7385–7392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1520-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Desai NS, Casimiro TM, Gruber SM, Vanderklish PW. Early postnatal plasticity in neocortex of Fmr1 knockout mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1734–1745. doi: 10.1152/jn.00221.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Wilson BM, Cox CL. Absence of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated plasticity in the neocortex of fragile X mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2454–2459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610875104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Godfraind JM, Reyniers E, De Boulle K, D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP, Bakker CE, et al. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of fragile X knockout mice. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;64:246–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<246::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Paradee W, Melikian HE, Rasmussen DL, Kenneson A, Conn PJ, Warren ST. Fragile X mouse: strain effects of knockout phenotype and evidence suggesting deficient amygdala function. Neuroscience. 1999;94:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Larson J, Jessen RE, Kim D, Fine A-KS, du Hoffmann J. Age-dependent and selective impairment of long-term potentiation in the anterior piriform cortex of mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9460–9469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2638-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Lauterborn JC, Rex CS, Kramár E, Chen LY, Pandyarajan V, Lynch G, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10685–10694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hu H, Qin Y, Bochorishvili G, Zhu Y, van Aelst L, Zhu JJ. Ras signaling mechanisms underlying impaired GluR1-dependent plasticity associated with fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7847–7862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1496-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7746–7750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Hou L, Antion MD, Hu D, Spencer CM, Paylor R, Klann E. Dynamic translational and proteasomal regulation of fragile X mental retardation protein controls mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Neuron. 2006;51:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Dölen G, Bear MF. Role for metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in the pathogenesis of fragile X syndrome. J. Physiol. 2008;586:1503–1508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. [accessed September 23, 2014];Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991 615:125–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37754.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2039137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:657–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Gutierrez GC, Smalley SL, Tanguay PE. Autism in tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1998;28:97–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1026032413811. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9586771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Curatolo P, Napolioni V, Moavero R. Autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis: pathogenetic pathways and implications for treatment. J. Child Neurol. 2010;25:873–880. doi: 10.1177/0883073810361789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Hunt A, Dennis J. PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER AMONG CHILDREN WITH TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008;29:190–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1987.tb02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. [accessed September 23, 2014];Science. 1997 277:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.805. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9242607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Kandt RS, Haines JL, Smith M, Northrup H, Gardner RJ, Short MP, et al. Linkage of an important gene locus for tuberous sclerosis to a chromosome 16 marker for polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 1992;2:37–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]