Abstract

Basophil-derived IL-4 is involved in the alternative activation of mouse monocytes, as recently shown in vivo. Whether this applies to human basophils and monocytes has not been established yet. Here, we sought to characterize the interaction between basophils and monocytes and identify the molecular determinants. A basophil-monocyte co-culture model revealed that IL-3 and basophil-derived IL-4 and IL-13 induced monocyte production of CCL17, a marker of alternative activation. Critically, IL-3 and IL-4 acted directly on monocytes to induce CCL17 production through histone H3 acetylation, but did not increase the recruitment of STAT5 or STAT6. Although freshly isolated monocytes did not express the IL-3 receptor α chain (CD123), and did not respond to IL-3 (as assessed by STAT5 phosphorylation), the overnight incubation with IL-4 (especially if associated with IL-3) upregulated CD123 expression. IL-3-activated JAK2-STAT5 pathway inhibitors reduced the CCL17 production in response to IL-3 and IL-4, but not to IL-4 alone. Interestingly, monocytes isolated from allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients exhibited a higher expression of CD123. Taken together, our data show that the JAK2-STAT5 pathway modulates both basophil and monocyte effector responses. The coordinated activation of STAT5 and STAT6 may have a major impact on monocyte alternative activation in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Allergy, Basophils, CCL17, Monocytes, JAK-STAT

Introduction

Type 2 immune responses are involved in conditions as diverse as allergy, tissue remodelling, parasitic infections [1, 2] and defence against animal venoms [3-5]. They are marked by the coordinated expression of Th2 cytokines (e.g. IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5) produced by several immune cell subsets (e.g. basophils, mast cells, innate lymphoid cells, NKT cells, and T lymphocytes). Interestingly, some in vivo models have uncovered a non-redundant role for basophils as a unique source of these cytokines [6].

Basophils are circulating granulocytes that account for less than 1% of blood leukocytes. Both human and mouse basophils express the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI). In response to IgE-dependent stimulation, they release a variety of preformed and de novo synthesized mediators, namely histamine, LTC4 and the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 that are hallmarks in allergic disease. In addition, circulating basophils express the IL-3 receptor α chain (IL-3Rα or CD123) for which binding of IL-3 is known to enhance every function of these cells, let alone its capacity to act on precursor cells to promote basopoiesis [7, 8]. Notwithstanding their rarity, basophils infiltrate inflamed tissue in several human diseases [9-12] and play a unique role in the development of some in vivo models of type 2 inflammation [6, 13, 14]. In a murine model of IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation (IgE-CAI) [15] as well as in the context of skin infestation by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis larvae [16], basophil-derived IL-4 induces the alternative (M2) activation of tissue-infiltrating inflammatory monocytes. Recently, it was shown that human basophils modulate LPS-induced proinflammatory activation of human monocytes [17]. It is currently unknown whether and how human basophils could modulate human monocyte/macrophage alternative activation.

Inflammatory monocytes (expressing Ly6C in mice and CD14 in humans) and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) are highly versatile effector cells owing to their ability to polarize in response to a wide spectrum of stimuli [18, 19]. Specifically, IL-4-induced STAT6 activation mediates the alternative activation of monocytes/macrophages which is characterized by increased expression of phagocytic receptors (e.g. the mannose receptor CD206) and the CCR4-binding chemokines CCL17/Thymus and activation regulated chemokine (TARC) and CCL22/Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC) [18, 20]. These two chemokines have been linked to type 2 immune disorders such as bronchial asthma [21-24] and atopic dermatitis [25-28] owing to their ability to recruit CCR4-expressing Th2 lymphocytes. Thus, identifying the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate human monocyte/macrophage alternative activation may be relevant for understanding their basic biology as well as type 2 immune disorders.

Using a human basophil-monocyte co-culture model, we found that IL-3 and basophil-derived IL-4/IL-13 induced CCL17 production by human monocytes. We provide evidence that the IL-3-JAK2-STAT5 pathway is directly involved in monocyte alternative activation and synergizes with IL-4-activated STAT6 in inducing CCL17 expression and chromatin remodelling at the CCL17 locus. The translational relevance of these findings was evaluated by showing that monocytes isolated from allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients express higher levels of CD123 compared to monocytes isolated from healthy controls.

Results

CCL17 production in human basophil-monocyte co-culture

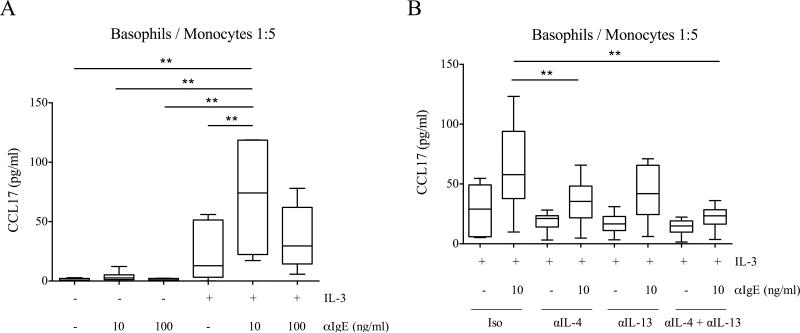

To investigate the hypothesis that human basophils can modulate monocyte alternative activation, we purified the two cell types from the same donor and co-cultured them at basophil:monocyte ratios of 1:5, 1:20 and 1:50. Cells were stimulated with different combinations of IL-3 and anti-IgE, the latter used at two different concentrations known to preferentially induce the release of IL-4 or histamine (i.e. 10 and 100 ng/ml, respectively) [29]. Although anti-IgE alone was insufficient to stimulate detectable CCL17 production, its combination with IL-3 resulted in relatively high levels of CCL17 (Fig. 1A). Although not shown herein, we also tested for induced expression of CD206 as a marker of monocyte alternative activation. However, IL-3 alone (in the absence of basophils) upregulated CD206 on monocytes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

CCL17 production in basophil-monocyte co-cultures. (A, B) Basophils and monocytes were co-cultured at a 1:5 ratio and stimulated with αIgE (10 or 100 ng/ml) and IL-3 (5 ng/ml) for 24 hours. CCL17 levels were measured by ELISA in cell-free supernatants. (B) Co-cultures were pretreated with IgG isotype control (Iso), αIL-4, αIL-13 or αIL-4 + αIL-13 15 minutes before adding stimuli. Data are shown as the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes) and the 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers) of 6 independent experiments. ** p < 0.01 determined by repeated measure one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

Importantly, purified basophils stimulated with IL-3 and anti-IgE did not release CCL17 (Supporting Information Fig. 1A), thus indicating monocytes as the source of this chemokine. IL-3 and anti-IgE induced low to no production of CCL17 by purified monocytes, implying the requirements for basophils in the co-cultures (Supporting Information Fig. 1B). Interestingly, CCL17 production was highest at an anti-IgE concentration of 10 ng/ml, which is the optimal dose for inducing cytokines from basophils [29]. This effect was evident at every basophil to monocyte ratio tested, suggesting the involvement of IL-4/IL-13 in mediating this monocyte response (Fig. 1A and Supporting Information Fig. 2). To test this hypothesis, we duplicated these conditions but in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-4, anti-IL-13, a combination of both or an isotype control. The concurrent blocking of IL-4 and IL-13 completely abolished the effect of anti-IgE and resulted in a marked reduction of CCL17 production (Fig. 1B).

IL-3 and IL-4 synergistically modulate monocyte CCL17 expression

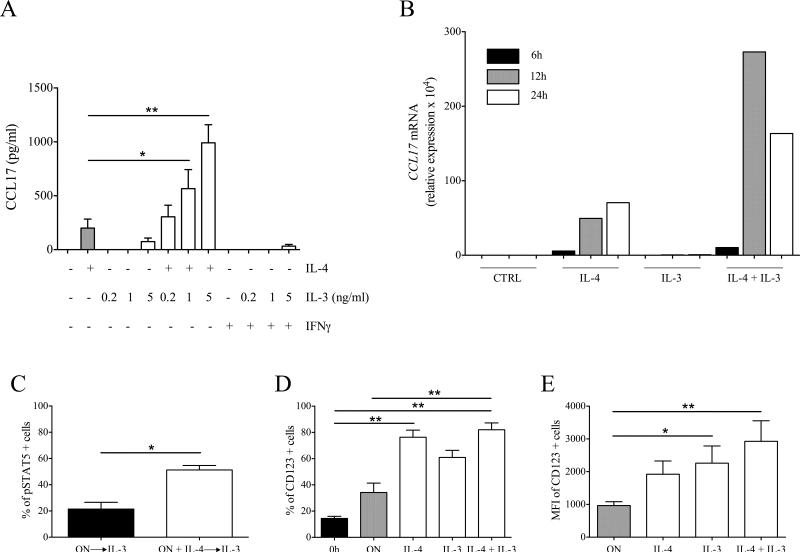

The results obtained with the co-culture model suggested that IL-3 and anti-IgE acted on basophils to induce IL-4 and IL-13 release, which in turn promoted CCL17 production by monocytes. Nonetheless, we reasoned that IL-3 may also be directly modulating the monocyte response and therefore proceeded to investigate this hypothesis. We stimulated monocytes with different combination of recombinant cytokines (i.e. IL-3, IL-4, IL-13 and IFN-γ). IL-4 but not IFN-γ induced CCL17 production from monocytes. Surprisingly, although IL-3 alone induced low to no production of CCL17, the combination of IL-3 and IL-4 markedly increased CCL17 expression (Fig. 2A). The same pattern of response was observed with MDM (Supporting Information Fig. 3) or when IL-13 was used instead of IL-4, although IL-13 was less potent in inducing CCL17 and it did not increase CCL17 production when added to monocytes stimulated with IL-3 and IL-4 (data not shown). A time-course analysis of CCL17 mRNA expression in monocytes stimulated with IL-3 and IL-4 showed a maximal expression at 12 hours and a decrease at 24 hours (Fig. 2B). We also tested the expression of CD206. Although IL-3 and IL-4 independently increased CD206 mRNA expression, their combination markedly upregulated CD206 (Supporting Information Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Monocyte responsiveness to IL-3. (A) Monocytes were stimulated with IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-3 (0.2, 1 or 5 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 24 hours. CCL17 levels were measured by ELISA in cell-free supernatants. (B) Monocytes were stimulated with IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-3 (1 ng/ml) and a combination of both. CCL17 mRNA levels are expressed as relative expression (normalized to GAPDH) × 104. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) Monocytes were cultured overnight with (ON + IL-4) or without (ON) IL-4 (10 ng/ml). Then, monocytes were stimulated with IL-3 (1 ng/ml). STAT5 phosphorylation was assessed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percentage of pSTAT5 positive cells. (D, E) Monocytes were cultured overnight without (ON) or with IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-3 (1 ng/ml), or both. CD123 expression was assessed by flow cytometry on cultured as well as freshly isolated (0h) monocytes. Results are expressed as (D) percentage and (E) MFI of CD123 positive cells. (A, C-E) Data are shown as mean + SEM of 4 (A), 6 (C) or 9 (D, E) independent experiments. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 determined by repeated measure one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (A, E), Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (C) and Friedman test with Dunn's post hoc test (D).

IL-3 belongs to a cytokine family that comprise also GM-CSF and IL-5 [30]. When these cytokines were used instead of IL-3, we observed that GM-CSF but not IL-5 increased CCL17 production when combined with IL-4 (Supporting Information Fig. 5). Furthermore, no production of IL-10 or IL-12p70 was observed in any of these cultures (Supporting Information Fig. 6), implying that the synergism between IL-3 (or GM-CSF) and IL-4 is specific for CCL17, a marker of monocyte/macrophage alternative activation.

Modulation of monocyte responsiveness to IL-3

The IL-3 receptor consists of a common β subunit (shared with GM-CSF and IL-5) and an IL-3 specific α subunit (CD123). The binding of IL-3 induces receptor heterodimerization and activation of the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway [30]. To identify the molecular basis of the synergism between IL-3 and IL-4, we performed short-term stimulations of freshly isolated monocytes with IL-3 and/or IL-4 and assessed STAT5 and STAT6 phosphorylation. Surprisingly, we did not identify relevant phosphorylation of STAT5 in any of the tested conditions (Supporting Information Fig. 7A). Furthermore, IL-3 did not modulate IL-4-induced STAT6 phosphorylation (Supporting Information Fig. 7B and C). Thus, we reasoned that long-term incubation with IL-4 could modulate monocyte responsiveness to IL-3. Accordingly, IL-3 stimulation of monocytes preincubated overnight (12 hours) with IL-4 induced STAT5 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). On the contrary, overnight preincubation with IL-3 did not modify the response to IL-4 (Supporting Information Fig. 8).

Confirming previous reported data [31], freshly isolated monocytes weakly expressed CD123, which in turn was markedly upregulated by overnight treatment with IL-4 (particularly in combination with IL-3) (Fig. 2D and E). These results were paralleled by STAT5 phosphorylation induced by IL-3 stimulation in monocytes preincubated overnight with IL-4, IL-3, or a combination of both (Supporting Information Fig. 9). No upregulation of CD123 was observed when IFN-γ, IL-10 or M-CSF were used instead of IL-4 and IL-3 (Supporting Information Fig. 10).

The JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway is required for CCL17 production

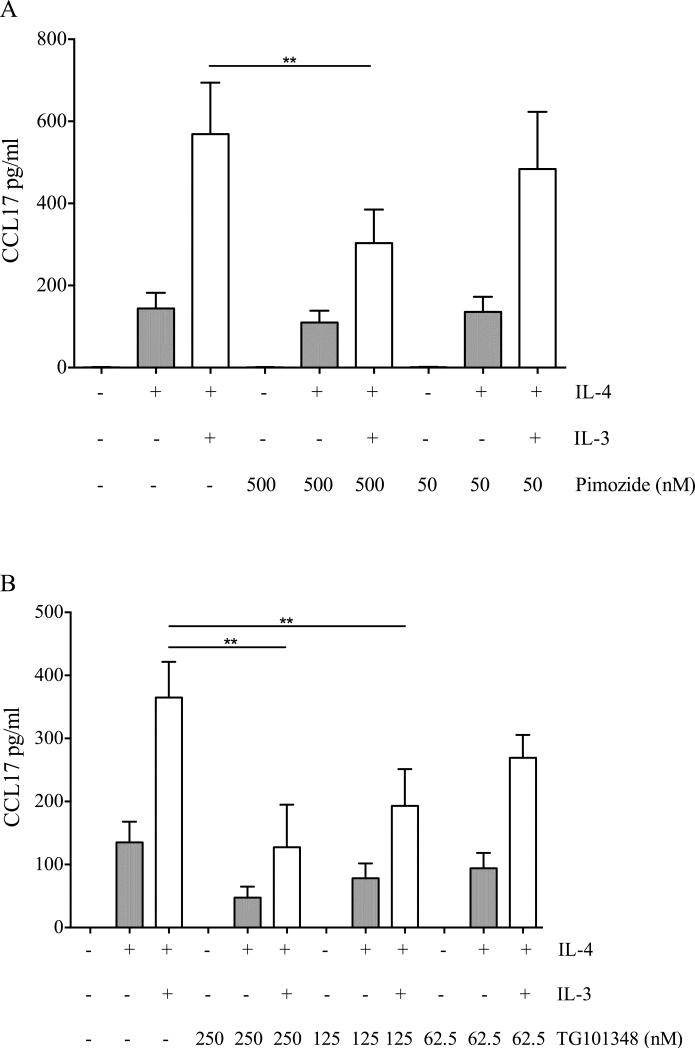

To assess the specific contribution of the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway to CCL17 production, we stimulated monocytes with IL-3 and IL-4 in the presence of different concentrations of pimozide (a STAT5 inhibitor) or TG101348 (a JAK2 inhibitor). To ascertain the specificity of these inhibitors, we stimulated monocytes also with IL-4 alone to identify those concentrations that do not affect CCL17 production in response to IL-4. Concurrently, we assessed the phosphorylation of STAT5 and STAT6 respectively in response to IL-3 and IL-4 in the presence of these inhibitors. Pimozide reduced CCL17 production in response to IL-3 and IL-4 (Fig. 3A). Although pimozide was reported to reduce STAT5 constitutive phosphorylation of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells [32], in our model it did not modulate IL-3- or IL-4-induced STAT5 and STAT6 phosphorylation, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. 11A-D). TG101348 also reduced CCL17 production in a dose-dependent manner. However, at a concentration of 250 nM it reduced the response to IL-4 (Fig. 3B). Consistently, at this concentration it reduced the phosphorylation of both STAT5 and STAT6, while at lower concentrations it preferentially modulated STAT5 (Supporting Information Fig. 11E-H). Interestingly, the specificity of TG101348 is concentration-dependent, with IC50s for JAK1, JAK2 and JAK3 being respectively 105, 3 and 1002 nM. As IL-4-induced STAT6 phosphorylation is mediated by JAK1 in human monocytes [33], it is conceivable that TG101348 at 250 nM inhibits both JAK2 and JAK1, while at lower concentrations is more specific for JAK2.

Figure 3.

Effect of the inhibition of the JAK2-STAT5 pathway on CCL17 production. Monocytes were preincubated with different concentrations of (A) pimozide (500 or 50 nM) or (B) TG101348 (250, 125 or 62.5 nM) and then stimulated with IL-4 (10 ng/ml) and IL-3 (1 ng/ml) for 24 hours. CCL17 levels were measured by ELISA in cell-free supernatants. (A, B) Data are shown as mean + SEM of 5 independent experiments. ** p < 0.01 determined by repeated measure one-way ANOVA with Sidak's post hoc test.

IL-3 and IL-4 modulate histone acetylation and transcription factor binding at the CCL17 locus

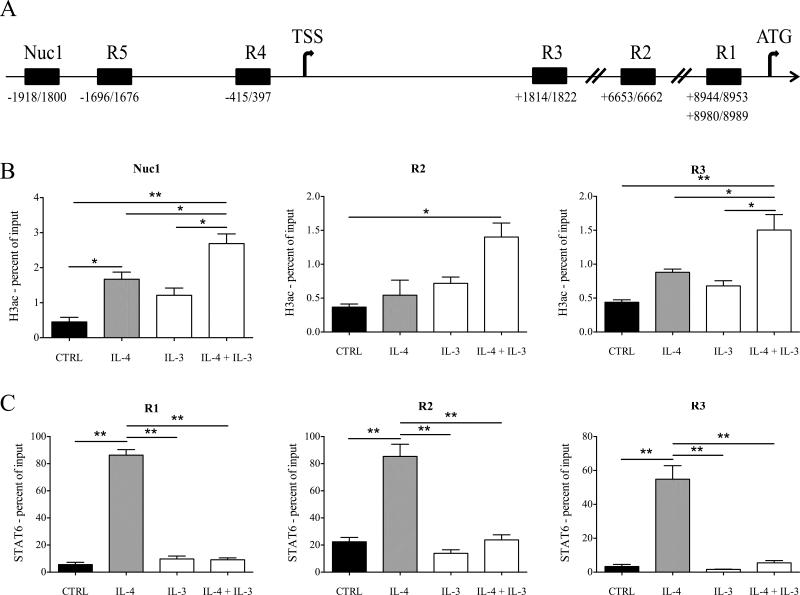

IL-4-induced CCL17 transcription is associated with STAT6 binding at three genomic regions in the first intron: two of them located ≈200 bp [34] and another one located ≈2500 bp [35] upstream of the translational start site (respectively R1 and R2, Fig. 4A). In addition, we identified 2 putative STAT5 binding sites within 2000 bp of the CCL17 transcriptional start site (TSS) (R4 and R5, Fig. 4A) by MatInspector software analysis, and another putative STAT binding site located ≈1800 bp downstream of CCL17 TSS by visual inspection of the first intron (R3, Fig. 4A). Thus, we asked whether IL-3 and IL-4 could modulate STAT5 and STAT6 binding and histone H3 acetylation (H3ac), which is a marker of actively transcribed genes [36], in these regions. Furthermore, we assessed H3ac in an additional region (Nuc1, Fig. 4A) located between 1800 and 1918 bp upstream of the CCL17 TSS. Consistent with gene expression data, IL-3 and IL-4 treatment increased H3ac both downstream (R2 and R3) and upstream (Nuc1) of the CCL17 TSS (Fig. 4B). IL-4 stimulation correlated with the recruitment of STAT6 at R1, R2 and also R3. Surprisingly, the combination of IL-3 and IL-4 reduced STAT6 binding at these regions (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, no association of STAT5 with any of the tested regions (R1-R5) was observed (data not shown).

Figure 4.

H3ac and STAT6 binding at the CCL17 locus. (A) Schematic representation of the CCL17 locus, including the transcriptional start site (TSS, chr16:57438679) and the translational start site (ATG, chr16:57447845). The positions of the tested regions (R1-R5, Nuc1) are indicated as relative to TSS. (B, C) Monocytes were cultured overnight without (CTRL) or with IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-3 (1 ng/ml) and a combination of both. H3ac and STAT6 binding was assessed by ChIP at Nuc1, R2, R3 (B) and R1, R2, R3 (C), respectively, and expressed as percent of input (B, C). Data are shown as mean + SEM of 3 independent experiments. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 determined by repeated measure one-way ANOVA with Sidak's post hoc test.

Monocytes isolated from asthmatic patients express higher levels of CD123

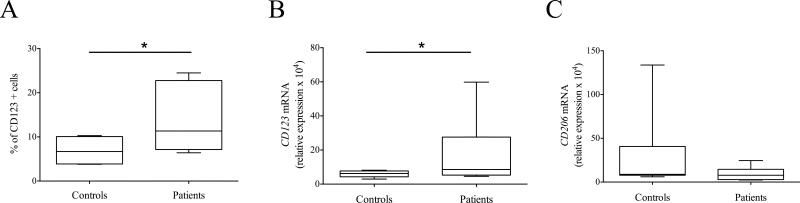

Our results suggest that the IL-3-JAK2-STAT5 pathway modulates monocyte alternative activation in vitro. To verify the in vivo relevance of this finding, we recruited allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients and age- and sex-matched healthy controls (Supporting Information Table 1). Monocytes were isolated from both groups and their expression of CD123, CD206 and CCL17 was assessed. CCL17 mRNA was increased only in one patient (interestingly the one with the highest eosinophil blood count and serum IgE levels), while it was undetectable in others (data not shown). Critically, monocytes isolated from asthmatic patients expressed higher levels of CD123 as assessed by flow cytometry and real time RT-PCR (Fig. 5, respectively A and B). No significant differences in CD206 mRNA expression were observed (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

CD123 and CD206 expression in monocytes isolated from asthmatic patients. CD123 and CD206 expression was assessed in monocytes isolated from 6 allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients (Patients) and 6 healthy controls (Controls) by means of flow cytometry (A) and real time RT-PCR (B, C). Results are expressed as (A) percentage of CD123 positive cells and (B, C) relative expression of CD123 and CD206 mRNA (normalized to GAPDH) × 104. (A-C) Data are shown as the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes) and the 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers) of 6 Patients and 6 Controls. * p < 0.05 determined by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that human basophils activated with IL-3 and anti-IgE induce CCL17 production by human monocytes. This effect is mediated by basophil-derived IL-4 and IL-13. In addition, IL-3 (as well as GM-CSF) acts on monocytes and synergizes with IL-4 to increase CCL17 production. Freshly isolated monocytes do not express CD123 or respond to IL-3 (as assessed by STAT5 phosphorylation). However, overnight incubation with IL-4 (especially if associated with IL-3) upregulates CD123 and makes monocytes responsive to IL-3. Although the IL-3-activated JAK2-STAT5 pathway is required for modulating CCL17 production, IL-3 reduces IL-4-induced STAT6 binding at the CCL17 locus without inducing STAT5 binding. The clinical relevance of these findings is supported by the observation that monocytes isolated from allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients express higher levels of CD123 compared to healthy donors.

In our co-culture model basophil-derived IL-4 and IL-13 were both required for maximal production of CCL17, while the addition of IL-13 to purified monocytes stimulated with IL-3 and IL-4 did not greatly improved CCL17 production. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by considering that IL-4 receptor α associates with common cytokine receptor γ chain to form the type I receptor complex and also couples with IL-13 receptor α1 to form the type II receptor complex. While IL-13 binds only the latter, IL-4 binds both [37]. Thus, it is conceivable that in the co-cultures IL-4 reached submaximal concentrations and IL-13 could bind its receptor complex. Instead, when purified monocytes were stimulated with supramaximal concentrations of IL-4, both receptor complexes were occupied and no additional effect of IL-13 could be observed.

IL-3 and its related family members GM-CSF and IL-5 modulate not only the production but also the effector functions of several hematopoietic cells [30]. For example, IL-3 acts on precursor cells to stimulate basopoiesis, but also on mature basophils to modulate mediator release and cytokine secretion [7, 8]. Murine bone marrow precursors treated with IL-3 differentiate into macrophages and basophils. The latter, especially in the absence SHIP, secrete high levels of IL-4, which in turn induces the alternative activation of macrophages [38]. Recently, it was shown that IL-3 upregulates CD206 expression on MDM [39]. Although previous studies reported that IL-3 modulates some functions of monocytes [40, 41], IL-3 and GM-CSF have been used mainly in combination with IL-4 to differentiate human monocytes into dendritic cells (DCs) after 5-7 days in culture [42, 43]. As the role of monocytes as effector cells has been recently revaluated [44], our analysis focused on the short-term (less than 24 hours) effects of IL-3 and IL-4 on monocytes. We aimed also to characterize the role of the IL-3-JAK2-STAT5 pathway in the context of monocyte/macrophage polarization. Specifically, we demonstrate that the concurrent activation of STAT5 (mediated by IL-3 or GM-CSF) and STAT6 (mediated by IL-4) potentiates the production of CCL17, a chemokine relevant to allergic inflammation [21-28]. Although we focused on a small set of cytokines and surface receptors, it will be interesting to perform a genome-wide analysis to evaluate in depth the contribution of STAT5 and STAT6 to monocyte/macrophage activation.

Both IL-3 and GM-CSF induce human monocyte differentiation into DCs in association with IL-4 [42, 43]. However, some differences exist between these two cytokines. IL-3-differentiated DCs have a greater ability than GM-CSF-differentiated DCs to polarize CD4 T lymphocytes toward a Th2 phenotype [42]. It is tempting to speculate that IL-3 and IL-4 mediate monocyte/macrophage alternative activation in the short-term and monocyte differentiation toward Th2-inducing DCs in the long-term. Thus, it will be interesting to assess whether basophils can modulate monocyte differentiation into DCs in a long-term co-culture model. Although several lines of evidence suggest that basophils are not major APCs in vitro and in vivo [6, 13], basophils activated by IL-3 and anti-IgE may provide essential mediators (e.g. IL-4 and IL-13) for differentiating monocytes into Th2-inducing DCs. These experiments will give a comprehensive picture of human basophil-monocyte interaction.

In this study we focused on cytokines that signal through the common β chain and activate the JAK2-STAT5 pathway. Another cytokine that activates STAT5 is thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) [45]. TSLP is produced by epithelial cells following stimulation with microbial and inflammatory stimuli and acts on cells expressing the TSLP receptor complex (a heterodimer composed of TSLP receptor [TSLPR] and IL-7 receptor α [IL-7Rα]) [37]. Several immune cell subsets are responsive to TSLP. In particular, TSLP-activated DCs induce Th2 differentiation and type 2 immunity in vitro and in vivo [46, 47]. Interestingly, TSLP and IL-4 or IL-13 synergize to induce CCL17 production by mouse macrophages [48]. These results strengthen our model according to which the combined action of STAT5- and STAT6-activating cytokines modulates monocyte/macrophage alternative activation. Nonetheless, in our experience freshly isolated human monocytes do not express TSLPR nor do they phosphorylate STAT5 in response to TSLP (unpublished observations). Further studies are required to define human monocyte responsiveness to TSLP.

Monocyte/macrophage activation is ultimately linked to the binding of transcription factors to responsive elements and the subsequent chromatin remodelling that modulates gene expression [49]. Although STAT6 binds at CCL17 locus and induces its expression [34, 35], IL-3 and IL-4 increased H3ac but unexpectedly reduced STAT6 binding. In addition, we could not identify STAT5 binding at the CCL17 locus. A hypothesis that may explain these discrepancies takes into consideration the nuclear localization of JAK2. Indeed, hematopoietic cells express JAK2 also in the nucleus where it mediates the phosphorylation of tyrosine 41 of histone H3 (H3Y41ph). This event, in turn, mediates the displacement of the heterochromatin protein HP1α and induces gene expression [50]. Interestingly, H3Y41ph has been mapped at a subset of active promoters in the absence of STAT5 binding [51]. It is tempting to speculate that the addition of IL-3 to IL-4 switches CCL17 regulation from STAT6-dependent to JAK2-dependent. However, we could not detect JAK2 in nuclear extracts of freshly isolated monocytes or monocytes stimulated overnight with IL-4 and/or IL-3 (Supporting Information Fig. 12). Further studies are required to define the global profiles of STAT5 and STAT6 binding sites and how they relate to chromatin regulatory elements in human monocytes.

Akin to many studies focused on human immune cells, ours do not provide mechanistic evidence in vivo that the IL-3-JAK2-STAT5 pathway is involved in monocyte alternative activation, nor that basophils interacts with monocytes. Nevertheless, we show that monocytes isolated from allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients express higher levels of CD123 but not CD206, a marker of alternative activation. Thus, it is unlikely that increased expression of CD123 reflects in vivo exposure of monocytes to IL-4 and/or IL-3. Rather, it may suggest increased mobilization of CD14+ bone marrow monocytes, which have been shown to express CD123 [52]. Indeed, increased mobilization of bone marrow precursors has been observed in several inflammatory conditions [53-57]. Further studies are required to investigate this hypothesis.

Taken together, our results confirm and extend those obtained in mouse models of type 2 inflammation according to which basophils induce monocyte alternative activation. We provide evidence that the IL-3-JAK2-STAT5 pathway is involved not only in basophil activation, but also in monocyte alternative activation. We also demonstrate that monocyte expression of CD123 is upregulated in allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients. Although the reasons for increased CD123 expression are unclear at present, it suggests that a “monocyte gene signature” might exist in atopic asthma and perhaps other allergic diseases. The definition of a “monocyte gene signature” will require a translational approach in which data arising from in vitro studies are tested in appropriate cohorts of patients, an approach that already led to the characterization of the molecular phenotypes of asthma [58]. Thus, studying how monocyte alternative activation is shaped by STAT5 and STAT6 signaling pathways may give new insights into both monocyte biology and the molecular signatures of allergic diseases.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study protocol involving the use of human blood cells was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Naples Federico II and by the Western Institutional Review Board (Seattle, Wash). Written informed consent was obtained from blood donors.

Cells were isolated from buffy coats of healthy donors. In selected experiments, monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood of asthmatic patients and age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Six allergen-sensitized asthmatic patients were enrolled in this study (Supporting Information Table 1), 5 of them were treatment-naïve and 1 was taking inhaled steroid and β2 agonists at the time of blood draw. Asthma severity was assessed by clinical examination and spirometry (FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio [% of predicted values]). Atopy was assessed by skin prick testing to common aeroallergens, eosinophil blood count and serum IgE levels. Both patients and healthy controls were nonsmokers and had no respiratory tract infections in the 6 weeks before the study.

Cell isolation and culture

Basophils and monocytes were enriched as previously described [59]. Alternatively, blood was layered onto Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich) and mononuclear cells were collected at the interface. Basophils and monocytes were further purified with Basophil Isolation Kit II and CD14 Microbeads, respectively (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity of cell preparations was > 98% as assessed by alcian blue staining (basophils) or flow cytometry (monocytes).

Cells were cultured in cIMDM-5 (IMDM, 5% FCS, 1x non essential amino acids, 1x UltraGlutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 5 μ/ml gentamicin [Lonza]) in 96-well flat-bottom plates in a final volume of 250 μl. Monocytes (2 × 105) were added to each well and cultured alone and with basophils added at the indicated basophil to monocyte ratio. For experiments involving flow cytometry, cells were cultured in 1.5 ml tubes, then spun down and collected for the subsequent staining protocols. For monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), monocytes were cultured (5 × 104 cells/well in 96 well flat bottom plates) for 7 days in cRPMI-10 (RPMI, 10% FCS, 1x UltraGlutamine, 5 μ/ml gentamicin [Lonza]) + M-CSF 50 ng/ml (Miltenyi). Cells were treated with different combinations of: IL-3, IFN-γ, IL-10 (Peprotech), IL-4, IL-13, GM-CSF, IL-5 (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-human IL-4, anti-human IL-13, rat IgG1 κ isotype control (Biolegend), pimozide (Merck Millipore), and TG101348 (Selleck Chemicals). Polyclonal anti-IgE was kindly provided by Robert G. Hamilton (Johns Hopkins Asthma & Allergy Center, Baltimore, USA).

ELISA

Cytokine concentrations were measured in cell-free supernatants using commercially available ELISA kits for CCL17 (R&D Systems), and IL-10 and IL-12p70 (eBioscience). Standard curves were generated with a Four Parametric Logistic curve fit and data were analysed using MyAssays Analysis Software Solutions (www.myassays.com).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry experiments were performed with purified monocytes. For surface staining, cells were stained (20 minutes at 4°C) in PBS + 10% human AB serum (Lonza) + 0.05% NaN3 (Staining buffer, SB). For phosphoprotein staining, cells were rested in cIMDM-5 for 1 hour and stimulated with the indicated cytokines for 15 minutes. Then, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (EM-grade, Electron Microscopy Sciences) (final concentration 1.5%) and permeabilized with absolute ice-cold methanol as previously described [60]. Cells were stained (30 minutes at room temperature) in SB. The following antibodies were used: anti-CD123 FITC (clone AC145, dilution 1:20), anti-CD206 FITC (clone DCN228, dilution 1:20) (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-phospho-STAT5 AlexaFluor 647 (clone 47, dilution 1:20) and anti-phospho-STAT6 AlexaFluor 647 (clone 18, dilution 1:20) (BD Biosciences). Samples were acquired on a BD LSRFortessa and analyzed using FACSDiva Software. Data are expressed as percentage of positive cells and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of positive cells. Gating strategies for surface staining and phosphoprotein staining are shown in Supporting Information Fig. 13 and Fig. 14, respectively.

RNA isolation and real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA was performed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. Real time RT-PCR was performed in triplicate by using iQ SYBR Green Supermix on iCycler real time detection system (Bio-Rad). Relative quantification of gene expression was calculated by the ΔCt (relative expression × 104) method. Each Ct value was normalized to the respective glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Ct value. The following primer pairs were used: CCL17 forward 5’-tccagggatgccatcgttttt-3’; CCL17 reverse 5’-tccctcactgtggctcttct-3’; CD123 forward 5’-ggtgcggagaatctgacctg-3’; CD123 reverse 5’-gtactgttgacgcctgttgg-3’; CD206 forward 5’-cgatccgacccttccttgac-3’; CD206 reverse 5’-tgtctccgcttcatgccatt-3’; GAPDH forward 5’-cgctctctgctcctcctgttc-3’; GAPDH reverse 5’-ttgactccgaccttcaccttcc-3’.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

Upon protein-DNA cross-linking, cells were lysed and sonicated to achieve chromatin fragments ranging between 200 and 1000 bp in size. The lysates were incubated with anti-H3Ac (Millipore), anti-STAT5 (Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-STAT6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or isotype controls, and then complexes were isolated using Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen). Immunoprecipitates were extensively washed and then eluted with freshly prepared 1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer. After reversion of cross-linking and deproteinization, DNA was purified with QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) followed by real time PCR analysis. The following primer pairs were used: R1 forward 5’-cagctgtgcgtggaggcttttca-3’; R1 reverse 5’-tccttccctagaccagtgaagttcgaaga-3’; R2 forward 5’-tgcaccagccttgaactgaaccag-3’; R2 reverse 5’-gctacacaactgcaagggacagctgatta-3’; R3 forward 5’-ccaccccagcctatagtgag-3’; R3 reverse 5’-tagtctccagctggctcagg-3’; R4 forward 5’-cgttctgaacacgggagat-3’; R4 reverse 5’-tgggtgagctcatgtctctg-3’; R5 forward 5’-gcctaccatgtgccgagata-3’; R5 reverse 5’-agattacatctttcagtgaagtcaa-3’; Nuc1 forward 5’-gcctaccatgtgccgagata-3’; Nuc1 reverse 5’-tgtttactatctgtctcccacctg-3’.

Western blot analysis

For pSTAT5 detection, cells were lysed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared by using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific). 10 μg of protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with the following antibodies: anti-phospho-STAT5 (#9351, dilution 1:1000), anti-STAT5 (#4459, dilution 1:1000), anti-JAK2 (#3230, dilution 1:1000) (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-α-tubulin (#T9026, dilution 1:5000) (Sigma) and anti-lamin A/C (#sc-6215, dilution 1:500).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). p values were calculated with paired t test or repeated measure one-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons unless otherwise indicated. Flow cytometry percentage data were analysed by using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or Friedman test corrected for multiple comparisons. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca (MIUR) and Regione Campania CISI-Lab Project, CRÈME Project and TIMING Project (G.M.), grants from the Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca (MIUR) PRIN, FIRB-MERIT, PON 01_02460, and Regione Campania CRÈME Project (F.Be.), and grants R56 AI091631 and R01 AI115703 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, USA (J.T.S.).

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- DCs

dendritic cells

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in the 1st second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- H3ac

acetyl-histone H3

- JAK

just another kinase

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- pSTAT

phospho-STAT

- TSS

transcriptional start site

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gause WC, Wynn TA, Allen JE. Type 2 immunity and wound healing: evolutionary refinement of adaptive immunity by helminths. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nri3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulendran B, Artis D. New paradigms in type 2 immunity. Science. 2012;337:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1221064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Medzhitov R. Allergic host defences. Nature. 2012;484:465–472. doi: 10.1038/nature11047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Yu S, Schenten DD, Florsheim E, Medzhitov R. Bee venom phospholipase A2 induces a primary type 2 response that is dependent on the receptor ST2 and confers protective immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marichal T, Starkl P, Reber LL, Kalesnikoff J, Oettgen HC, Tsai M, Metz M, et al. A beneficial role for immunoglobulin E in host defense against honeybee venom. Immunity. 2013;39:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karasuyama H, Yamanishi Y. Basophils have emerged as a key player in immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014;31C:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voehringer D. Basophil modulation by cytokine instruction. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012;42:2544–2550. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder JT. Basophils: emerging roles in the pathogenesis of allergic disease. Immunol. Rev. 2011;242:144–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito Y, Satoh T, Takayama K, Miyagishi C, Walls AF, Yokozeki H. Basophil recruitment and activation in inflammatory skin diseases. Allergy. 2011;66:1107–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouri-Aria KT, Irani AM, Jacobson MR, O'Brien F, Varga EM, Till SJ, Durham SR, et al. Basophil recruitment and IL-4 production during human allergen-induced late asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108:205–211. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Paulis A, Prevete N, Fiorentino I, Rossi FW, Staibano S, Montuori N, Ragno P, et al. Expression and functions of the vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors in human basophils. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7322–7331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Paulis A, Prevete N, Fiorentino I, Walls AF, Curto M, Petraroli A, Castaldo V, et al. Basophils infiltrate human gastric mucosa at sites of Helicobacter pylori infection, and exhibit chemotaxis in response to H. pylori- derived peptide Hp(2-20). J. Immunol. 2004;172:7734–7743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borriello F, Granata F, Marone G. Basophils and skin disorders. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134:1202–1210. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siracusa MC, Kim BS, Spergel JM, Artis D. Basophils and allergic inflammation. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.046. quiz 788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egawa M, Mukai K, Yoshikawa S, Iki M, Mukaida N, Kawano Y, Minegishi Y, et al. Inflammatory monocytes recruited to allergic skin acquire an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype via basophil-derived interleukin-4. Immunity. 2013;38:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obata-Ninomiya K, Ishiwata K, Tsutsui H, Nei Y, Yoshikawa S, Kawano Y, Minegishi Y, et al. The skin is an important bulwark of acquired immunity against intestinal helminths. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2583–2595. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivellese F, Suurmond J, de Paulis A, Marone G, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. IgE and IL-33-mediated triggering of human basophils inhibits TLR4-induced monocyte activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:3045–3055. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue J, Schmidt SV, Sander J, Draffehn A, Krebs W, Quester I, De Nardo D, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. 2014;40:274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikhak Z, Fukui M, Farsidjani A, Medoff BD, Tager AM, Luster AD. Contribution of CCR4 and CCR8 to antigen-specific T(H)2 cell trafficking in allergic pulmonary inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;123:67–73 e63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijayanand P, Durkin K, Hartmann G, Morjaria J, Seumois G, Staples KJ, Hall D, et al. Chemokine receptor 4 plays a key role in T cell recruitment into the airways of asthmatic patients. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4568–4574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perros F, Hoogsteden HC, Coyle AJ, Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Blockade of CCR4 in a humanized model of asthma reveals a critical role for DC-derived CCL17 and CCL22 in attracting Th2 cells and inducing airway inflammation. Allergy. 2009;64:995–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panina-Bordignon P, Papi A, Mariani M, Lucia PD, Casoni G, Bellettato C, Buonsanti C, et al. The C-C chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 identify airway T cells of allergen-challenged atopic asthmatics. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:1357–1364. doi: 10.1172/JCI12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vestergaard C, Yoneyama H, Murai M, Nakamura K, Tamaki K, Terashima Y, Imai T, et al. Overproduction of Th2-specific chemokines in NC/Nga mice exhibiting atopic dermatitis-like lesions. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:1097–1105. doi: 10.1172/JCI7613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng X, Nakamura K, Furukawa H, Nishibu A, Takahashi M, Tojo M, Kaneko F, et al. Demonstration of TARC and CCR4 mRNA expression and distribution using in situ RT-PCR in the lesional skin of atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. 2003;30:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsunemi Y, Saeki H, Nakamura K, Nagakubo D, Nakayama T, Yoshie O, Kagami S, et al. CCL17 transgenic mice show an enhanced Th2- type response to both allergic and non-allergic stimuli. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:2116–2127. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakinuma T, Nakamura K, Wakugawa M, Mitsui H, Tada Y, Saeki H, Torii H, et al. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine in atopic dermatitis: Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine level is closely related with disease activity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;107:535–541. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.113237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder JT, MacGlashan DW, Jr., Kagey-Sobotka A, White JM, Lichtenstein LM. IgE-dependent IL-4 secretion by human basophils. The relationship between cytokine production and histamine release in mixed leukocyte cultures. J. Immunol. 1994;153:1808–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broughton SE, Dhagat U, Hercus TR, Nero TL, Grimbaldeston MA, Bonder CS, Lopez AF, et al. The GM-CSF/IL-3/IL-5 cytokine receptor family: from ligand recognition to initiation of signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2012;250:277–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leveque C, Grafte S, Paysant J, Soutif A, Lenormand B, Vasse M, Soria C, et al. Regulation of interleukin 3 receptor alpha chain (IL-3R alpha) on human monocytes by interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, IL-13, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta). Cytokine. 1998;10:487–494. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson EA, Walker SR, Weisberg E, Bar-Natan M, Barrett R, Gashin LB, Terrell S, et al. The STAT5 inhibitor pimozide decreases survival of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells resistant to kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2011;117:3421–3429. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharjee A, Shukla M, Yakubenko VP, Mulya A, Kundu S, Cathcart MK. IL-4 and IL-13 employ discrete signaling pathways for target gene expression in alternatively activated monocytes/macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;54:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirnsberger G, Hebenstreit D, Posselt G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A. IL-4 induces expression of TARC/CCL17 via two STAT6 binding sites. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:1882–1891. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier E, Wirnsberger G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A, Hebenstreit D. Identification of a distal tandem STAT6 element within the CCL17 locus. Hum. Immunol. 2007;68:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northrup DL, Zhao K. Application of ChIP-Seq and related techniques to the study of immune function. Immunity. 2011;34:830–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romeo MJ, Agrawal R, Pomés A, Woodfolk JA. A molecular perspective on TH2-promoting cytokine receptors in patients with allergic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;133:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuroda E, Ho V, Ruschmann J, Antignano F, Hamilton M, Rauh MJ, Antov A, et al. SHIP represses the generation of IL-3-induced M2 macrophages by inhibiting IL-4 production from basophils. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3652–3660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cardone M, Ikeda KN, Varano B, Belardelli F, Millefiorini E, Gessani S, Conti L. Opposite regulatory effects of IFN-β and IL-3 on C-type lectin receptors, antigen uptake, and phagocytosis in human macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014;95:161–168. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alderson MR, Armitage RJ, Tough TW, Ziegler SF. Synergistic effects of IL-4 and either GM-CSF or IL-3 on the induction of CD23 expression by human monocytes: regulatory effects of IFN-alpha and IFN-gamma. Cytokine. 1994;6:407–413. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomssen H, Kahan M, Londei M. IL-3 in combination with IL-4, induces the expression of functional CD1 molecules on monocytes. Cytokine. 1996;8:476–481. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebner S, Hofer S, Nguyen VA, Furhapter C, Herold M, Fritsch P, Heufler C, et al. A novel role for IL-3: human monocytes cultured in the presence of IL-3 and IL-4 differentiate into dendritic cells that produce less IL- 12 and shift Th cell responses toward a Th2 cytokine pattern. J. Immunol. 2002;168:6199–6207. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and allergic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;130:845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell BD, Kitajima M, Larson RP, Stoklasek TA, Dang K, Sakamoto K, Wagner KU, et al. The transcription factor STAT5 is critical in dendritic cells for the development of TH2 but not TH1 responses. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:364–371. doi: 10.1038/ni.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arima K, Watanabe N, Hanabuchi S, Chang M, Sun SC, Liu YJ. Distinct signal codes generate dendritic cell functional plasticity. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han H, Headley MB, Xu W, Comeau MR, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin amplifies the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013;190:904–912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson MA, Bannister AJ, Gottgens B, Foster SD, Bartke T, Green AR, Kouzarides T. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature. 2009;461:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dawson MA, Foster SD, Bannister AJ, Robson SC, Hannah R, Wang X, Xhemalce B, et al. Three distinct patterns of histone H3Y41 phosphorylation mark active genes. Cell. Rep. 2012;2:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silbermann R, Bolzoni M, Storti P, Guasco D, Bonomini S, Zhou D, Wu J, et al. Bone marrow monocyte-/macrophage-derived activin A mediates the osteoclastogenic effect of IL-3 in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2014;28:951–954. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griseri T, McKenzie BS, Schiering C, Powrie F. Dysregulated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell activity promotes interleukin-23-driven chronic intestinal inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:1116–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, Kollnberger M, Tubo N, Moseman EA, Huff IV, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Perrigoue JG, Spencer SP, Urban JF, Jr., Tocker JE, Budelsky AL, et al. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature. 2010;464:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/nature08901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Osborne LC, Ziegler CG, Benitez AJ, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated extramedullary hematopoiesis promotes allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2013;39:1158–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allakhverdi Z, Comeau MR, Smith DE, Toy D, Endam LM, Desrosiers M, Liu YJ, et al. CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells are potent effectors of allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;123:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 2012;18:716–725. doi: 10.1038/nm.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Schroeder JT. Cellular immune response parameters that influence IgE sensitization. J. Immunol. Methods. 2012;383:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schulz KR, Danna EA, Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Single-cell phospho-protein analysis by flow cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter. 2012;8:20. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0817s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.