Abstract

Di-2-pyridylketone 4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT) demonstrates potent anti-cancer activity. We previously demonstrated that 14C-Dp44mT enters and targets cells through a carrier/receptor-mediated uptake process. Despite structural similarity, 2-benzoylpyridine 4-ethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Bp4eT) and pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone (PIH) enter cells via passive diffusion. Considering albumin alters the uptake of many drugs, we examined the effect of human serum albumin (HSA) on the cellular uptake of Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH. Chelator-HSA binding studies demonstrated the following order of relative affinity: Bp4eT≈PIH>Dp44mT. Interestingly, HSA decreased Bp4eT and PIH uptake, potentially due to its high affinity for the ligands. In contrast, HSA markedly stimulated Dp44mT uptake by cells, with two saturable uptake mechanisms identified. The first mechanism saturated at 5-10 μM (Bmax:1.20±0.04 × 107 molecules/cell; Kd:33±3 μM) and was consistent with a previously identified Dp44mT receptor/carrier. The second mechanism was of lower affinity, but higher capacity (Bmax:2.90±0.12 × 107 molecules/cell; Kd:65±6 μM), becoming saturated at 100 μM and was only evident in the presence of HSA. This second saturable Dp44mT uptake process was inhibited by excess HSA and had characteristics suggesting it was mediated by a specific binding site. Significantly, the HSA-mediated increase in the targeting of Dp44mT to cancer cells potentiated apoptosis and could be important for enhancing efficacy.

Keywords: Albumin, Dp44mT, Anti-tumor targeting, Human serum albumin

INTRODUCTION

Various exogenous compounds, including drugs such as warfarin [1], chlorpromazine [2], digitoxin [2] and ibuprofen [2], as well as endogenous molecules, such as fatty acids [3], steroids [4, 5] and inorganic ions [5, 6], bind extensively to albumin. In general, drug-protein interactions can adversely affect drug delivery by decreasing free drug levels available to traverse the plasma membrane to reach intracellular targets [7-9].

Conversely, albumin has also been demonstrated to aid the uptake and targeting of albumin-bound molecules, including fatty acids [5, 10, 11]. Studies have suggested that, upon binding to the cell membrane, albumin undergoes a conformational change, which subsequently results in the release of albumin-bound fatty acids [5, 11]. The release of the fatty acids in the vicinity of the membrane potentiates the delivery of these molecules to their receptor for cellular uptake [5, 11]. The subsequent reduced affinity of albumin for the cell surface then allows its release from the membrane [5, 11]. This mechanism has also been described for the cellular uptake of other albumin-bound molecules, such as testosterone and tryptophan, demonstrating the biological importance of albumin in the transport and delivery of a variety of ligands [5, 12-14].

Interestingly, albumin has been observed to accumulate within the interstitium of solid tumors [15-17]. This occurs due to the highly permeable tumor vasculature and the insufficient lymphatic drainage present in tumor tissue [15-17]. This characteristic is specifically known as the “enhanced permeability and retention effect” [15-17].

Thiosemicarbazone ligands are anti-cancer agents that bind metal ions and have shown anti-tumor activity in numerous investigations in vitro and in vivo, including many clinical trials [18-22]. As part of a specific strategy to generate selective and active anti-tumor agents, the di-2-pyridylketone thiosemicarbazones were developed [18, 19, 23-25]. In particular, the ligand, di-2-pyridylketone 4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT; Fig. 1A) and its analogs, were shown to have potent in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity [18, 24-26] and to possess marked anti-metastatic efficacy [27-29]. Additionally, the activity of Dp44mT was potentiated in drug-resistant cancer cells [24].

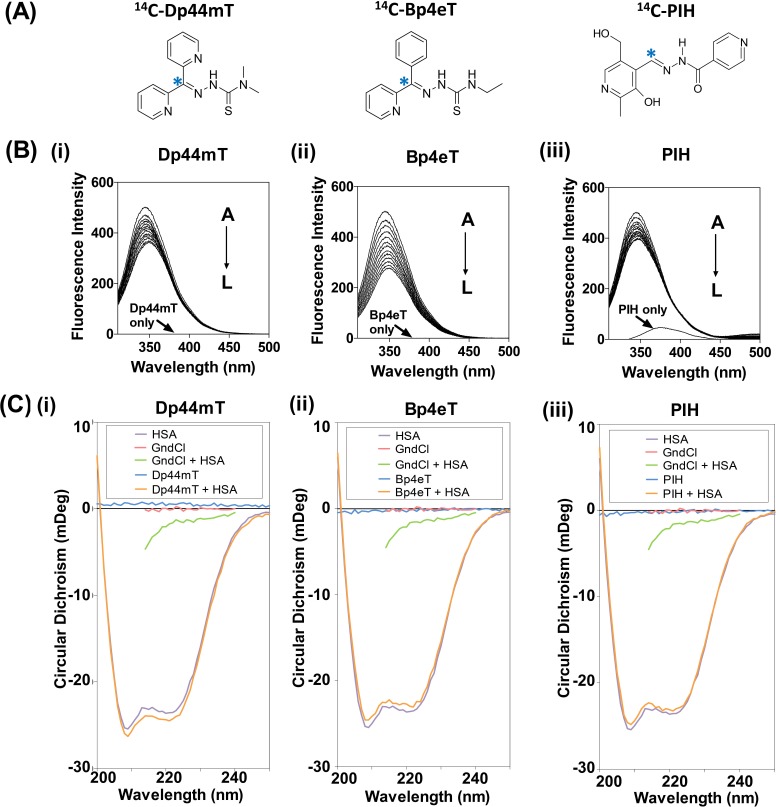

Figure 1. (A): Line drawings of the chemical structures of the iron chelators: di-2-pyridylketone 4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT), 2-benzoylpyridine 4-ethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Bp4eT) and pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone (PIH).

Asterisk (*) indicates position of the 14C-label. (B) Fluorescence emission spectrum of HSA (2 μM) excited at 295 nm in the presence of increasing concentrations (A→L; 0-3.67 μM) of: (i) Dp44mT; (ii) Bp4eT; or (iii) PIH in PBS at 37°C/pH 7.4. (C) Circular dichroism of HSA (2 μM) in the presence of: (i) Dp44mT, (ii) Bp4eT or (iii) PIH (10 μM) after a 2 h incubation at 37°C. Results shown are typical of 3 experiments performed.

In terms of its mechanism of action, Dp44mT accumulates within lysosomes, where it forms redox-active metal complexes [23, 25, 30] that mediate lysosomal membrane permeabilization to induce apoptosis [31]. Other modes of action include inhibition of the rate-limiting step of DNA synthesis that is catalyzed by ribonucleotide reductase [32] and up-regulation of N-myc downstream regulated gene 1 [33], resulting in inhibition of proliferation and metastasis, respectively [24, 26, 27].

Interestingly, it has been recently demonstrated that Dp44mT binds to a saturable receptor/carrier on a variety of cell-types [34]. Other structurally-related thiosemicarbazones, such as 2-benzoylpyridine 4-ethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Bp4eT; Fig. 1A), or aroylhydrazones (e.g., pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone, PIH; Fig. 1A), entered cells via a non-saturable mechanism consistent with passive diffusion [34, 35]. The role of this receptor/carrier in targeting Dp44mT to cancer cells could be important for explaining the marked anti-tumor and anti-metastatic activity, which markedly surpasses other similar agents [18, 24-29].

Considering the increased distribution of albumin in the tumor interstitium and the crucial role of this protein as a drug shuttle [36], it was critical to evaluate the interaction between Dp44mT and albumin. In order to understand the importance of key structural features of Dp44mT in its uptake, studies were performed in comparison to the related ligands, Bp4eT and PIH (Fig. 1A), which possess high and low anti-proliferative activity, respectively [37, 38].

Herein, for the first time, we describe a novel mechanism involved in the cellular uptake and targeting of Dp44mT that is markedly facilitated by human serum albumin (HSA). Intriguingly, this process is distinct from Dp44mT's structurally similar analogs, Bp4eT and PIH, whose cellular uptake was inhibited by HSA. Two saturable mechanisms of Dp44mT uptake by cells were identified. The first uptake mechanism saturated at 5-10 μM, and this observation was consistent with the previously identified Dp44mT receptor/carrier [34]. In contrast, the second mechanism of Dp44mT uptake was a low affinity, high capacity process which saturated at >100 μM and was only evident in the presence of HSA. The enhanced uptake of Dp44mT by HSA was identified in multiple neoplastic cell-types and a normal cell-type. Moreover, the HSA-mediated increase in Dp44mT uptake was specific for this protein and was inhibited by excess HSA. The enhanced cellular targeting of Dp44mT by HSA potentiated the anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of the agent, facilitating its anti-tumor efficacy.

RESULTS

Fluorescence Quenching of HSA by Chelators Indicates Direct Ligand-Binding

Fluorescence spectroscopy was initially used to examine the ability of the ligands to bind HSA (Fig. 1Bi-iii). It is well known that HSA contains a single tryptophan (Trp-214) situated in sub-domain IIA that fluoresces upon excitation at 295 nm [39, 40]. The conformational state of HSA can influence the exposure of this tryptophan residue, and thereby affect tryptophan fluorescence [39].

HSA alone had a pronounced fluorescence maximum at 345 nm (Fig. 1Bi-iii), due to Trp-214 [5]. No minimal intrinsic fluorescence was demonstrated for Dp44mT, Bp4eT, or PBS alone (Fig. 1Bi, ii). In contrast, some intrinsic fluorescence was observed for PIH (Fig. 1Biii). The fluorescence intensity of HSA decreased with increasing concentrations of all the ligands (i.e., A→L; 0-3.67 μM chelator concentrations; see Fig. 1Bi-iii), indicating the interaction of these agents with HSA.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy Demonstrated No Secondary Conformational Alteration in HSA after Incubation with Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH

To determine whether the ligands induce a change in the protein conformation of HSA, changes in protein secondary structure after incubation with Dp44mT, Bp4eT, or PIH, were examined using CD spectroscopy (Fig. 1Ci-iii). The CD spectrum of HSA exhibited two negative peaks at 208 and 222 nm that are characteristic of its predominantly α-helical structure (Fig. 1Ci-iii) [41]. In fact, analysis of the secondary structure revealed 67.73% α-helices (Table 1), which is in agreement with the X-ray crystal structure of HSA [42]. Importantly, no marked alterations in secondary structure were detected after incubation with these ligands (Fig. 1Ci-iii), resulting in similar levels of α-helical secondary structure content (66.86 – 67.84%; Table 1). Interestingly, minimal levels of β-sheet content (5.91%; Table 1) were detected and were not appreciably altered in the presence of the chelators (5.82-6.02%; Table 1). As previously observed [43], the chaotrope and positive control for protein folding, guanidine hydrochloride (GndCl), resulted in the denaturation of HSA (Fig. 1Ci-iii), as demonstrated by a decrease in α-helix content to 1.79%, and the simultaneous increase in β-sheet content to 34.84% (Table 1). Collectively, these results suggest the ligands, Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH, do not mediate significant changes in the secondary structure of HSA upon binding.

Table 1. The effect of the ligands, Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH, or the chaotropic agent, guanidine hydrochloride (GndCl), on α-helix and β-sheet content of HSA.

| % α-Helix | % β-Sheets | |

|---|---|---|

| HSA | 67.73% | 5.91% |

| HSA + Dp44mT | 67.84% | 5.89% |

| HSA + Bp4eT | 66.86% | 6.02% |

| HSA + PIH | 67.17% | 5.82% |

| HSA + GndCl* | 1.79% | 34.84% |

Note: GndCl is used as a positive control to induce alterations in HSA secondary structure.

14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH Bind to HSA More Avidly than 14C-Dp44mT

Further studies were then performed to characterize the binding of the ligands to HSA using the equilibrium dialysis technique [44]. In these experiments, a physiologically-relevant concentration of HSA in the plasma (40 mg/mL; [41, 45]) was pre-incubated with the 14C-chelators (25 μM) for 2 h/37°C to duplicate the incubation period used in subsequent experiments examining uptake of the 14C-ligands by cells. BSA (40 mg/mL) was chosen as a control protein since it possesses 75.6% sequence identity with HSA [5]. These solutions were then placed into dialysis sacs and the release of the 14C-chelators from the sac into the dialysate was then examined after 24 h/4°C to ensure equilibrium (Fig. 2A).

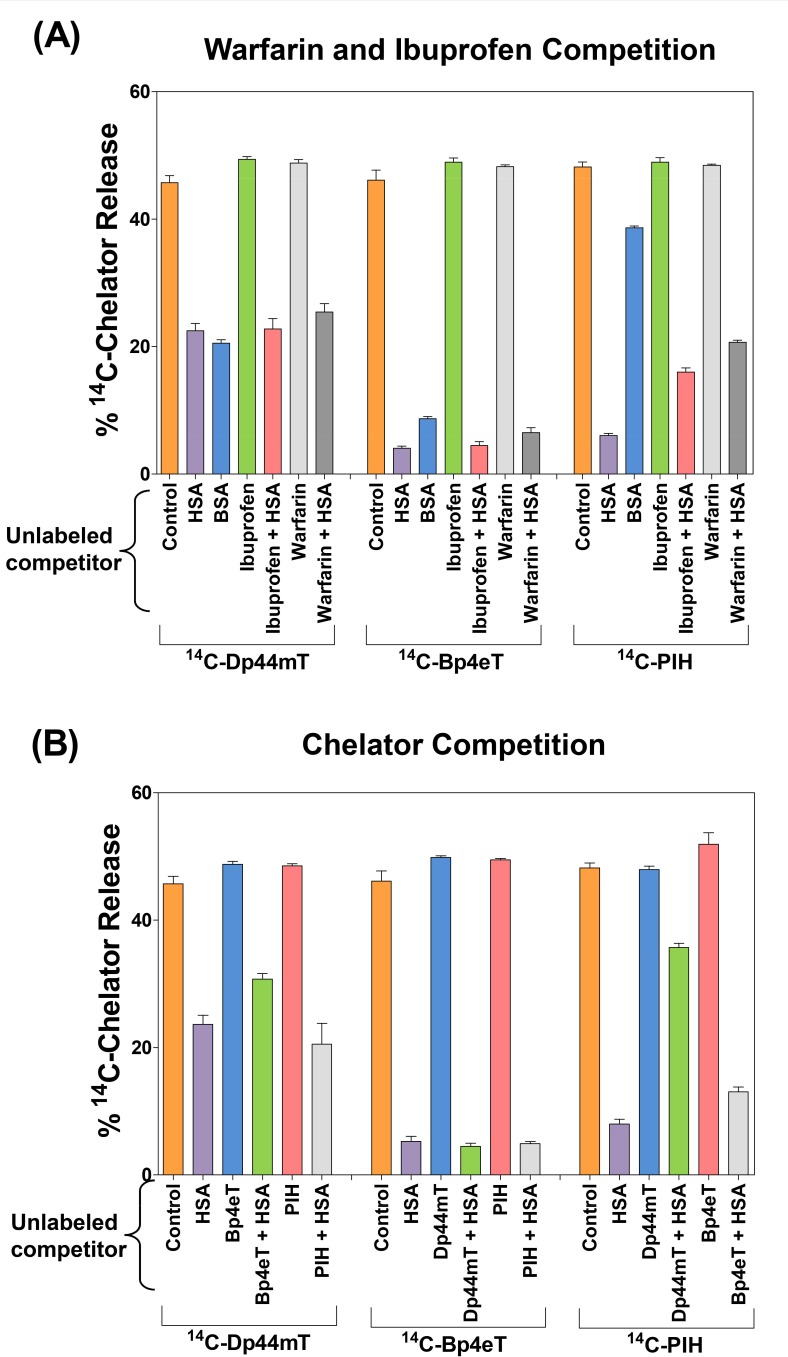

Figure 2. Equilibrium dialysis studies demonstrating the binding of Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH to albumin.

In these studies, HSA or BSA (40 mg/mL) was pre-incubated with the 14C-chelators (25 μM) for 2 h/37°C and placed into dialysis sacs and the release of the 14C-chelators from the dialysis sac into the dialysate was then examined after a 24 h/4°C equilibration period. For competition studies: (A) HSA (40 mg/mL) was pre-incubated for 2 h/37°C with a 200-fold excess of unlabeled warfarin or ibuprofen (5 mM), or (B) a 20-fold excess of unlabeled Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH (0.5 mM). Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of at least 3 experiments.

In the absence of protein (i.e., see “control” in Fig. 2A), dialysis of 14C-ligands was performed against the buffer-only control and led to the release of ≈ 50% of each of the 14C-ligands from the dialysis sac into the dialysate (Fig. 2A). This observation demonstrated that the incubation period was sufficient to establish the equilibrium of these low molecular weight ligands between the dialysis sac and dialysate.

The presence of HSA inside the dialysis sac resulted in a marked and significant (p<0.001) decrease in the release of 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH into the dialysate to 22.0 ± 1.0%, 4.0 ± 0.3% and 6.0 ± 0.3%, respectively, compared to the relative control (i.e., control sacs without HSA; Fig. 2A). These results demonstrated that the 14C-ligands were directly binding to HSA and being retained in the dialysis sac. Clearly, HSA retained the 14C-labeled ligands to different extents, with 14C-Dp44mT binding significantly (p<0.001) less avidly than either 14C-Bp4eT or 14C-PIH, which bound to HSA with approximately similar avidity (Fig. 2A). These findings indicate the relative binding affinity of the ligands for HSA to be in the following order: 14C-Bp4eT ≈14C-PIH > 14C-Dp44mT (Fig. 2A).

Moreover, BSA (40 mg/mL) also significantly (p<0.001) decreased the percentage of 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH released from the sac to 21 ± 0.5%, 9 ± 0.3% and 39 ± 0.3%, respectively, compared to control (i.e., control sacs without protein; Fig. 2A). Further, no significant difference (p>0.05) in the binding of Dp44mT to either HSA or BSA was evident (Fig. 2A). These data also demonstrate that Bp4eT and PIH bind BSA significantly (p<0.001) less avidly relative to HSA.

Considering the HSA-binding described above, we next examined if the 14C-ligands (25 μM) bind to the classical drug-binding sites of HSA, namely, Sudlow's site I and/or site II [5]. In these studies, a standard competition protocol was used, whereby HSA (40 mg/mL) was pre-incubated for 2 h/37°C with a 200-fold excess of unlabeled warfarin or ibuprofen (5 mM; Fig. 2A) that bind to Sudlow's sites I or II, respectively [5]. The 14C-chelators (25 μM) were then added and the samples further incubated for 2 h/37°C, followed by a 24 h/4°C dialysis period. As a control, in the absence of HSA, equilibrium dialysis of the 14C-ligands for 24 h/4°C was also performed in the presence of an excess of unlabeled ibuprofen or warfarin.

Irrespective of the excess warfarin or ibuprofen, the distribution of the 14C-ligands reached equilibrium (i.e., the 14C-ligand reached ≈50% in both the dialysis sac and dialysate) in the absence of HSA (Fig. 2A). In the presence of ibuprofen or warfarin and HSA, no significant (p>0.05) alteration in 14C-Dp44mT release from the dialysis sac occurred when compared to 14C-Dp44mT and HSA alone (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest that Dp44mT does not compete effectively with warfarin or ibuprofen at Sudlow's site I and II, respectively. Incubating HSA with a molar excess of warfarin, but not ibuprofen, led to a slight, albeit significant (p<0.01) increase in 14C-Bp4eT release from the dialysis sac when compared to HSA alone (Fig. 2A). This observation suggests that 14C-Bp4eT binds to a limited extent to Sudlow's site I, or in the vicinity of this site. More importantly, 14C-PIH release from the HSA-containing dialysis sac was markedly and significantly (p<0.001) increased in the presence of an excess of warfarin or ibuprofen, relative to the incubation of 14C-PIH with HSA alone (Fig. 2A).

Overall, these data suggest: (1) PIH either directly competes with warfarin and ibuprofen for Sudlow's sites I and II, respectively, or that PIH binds HSA at other sites that are allosterically modulated by warfarin- or ibuprofen-binding to HSA; (2) Bp4eT sparingly competes with warfarin at Sudlow's site I only; and (3) Dp44mT does not significantly (p>0.05) compete with warfarin or ibuprofen.

Competition Experiments Reveal HSA has Common and/or Interacting Binding Sites for the Ligands

Competition experiments using equilibrium dialysis were also used to evaluate if the three 14C-ligands became bound to a common, or different, site on HSA. Binding of 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT, or 14C-PIH (25 μM) to HSA was examined in competition with a 20-fold excess (0.5 mM) of the relevant unlabeled competitor ligand, namely Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH, which was pre-incubated with HSA for 2 h/37°C prior to adding the 14C-ligand (Fig. 2B). The unlabeled chelator could only be used at a 20-fold excess relative to the 14C-ligand due to their limited solubility. The solutions were then placed into dialysis sacs and the release of 14C-ligands from the dialysis sac into the dialysate examined after 24 h/4°C.

Incubation of HSA with an excess of unlabeled Bp4eT induced a slight, but significantly (p<0.05) increased release of 14C-Dp44mT from the dialysis sac relative to that found in the absence of this unlabeled ligand (Fig. 2B). This observation suggested competition between unlabeled Bp4eT and 14C-Dp44mT for a common HSA-binding region (Fig. 2B). However, no significant (p>0.05) change in the release of the 14C-label into the dialysate was evident when an excess of unlabeled PIH was incubated with 14C-Dp44mT and HSA relative to that found when 14C-Dp44mT and HSA were incubated together (Fig. 2B). Incubation of HSA with unlabeled Dp44mT or PIH had no significant effect on 14C-Bp4eT release from HSA (Fig. 2B). However, incubating HSA with an excess of unlabeled Dp44mT or Bp4eT significantly (p<0.001-0.05) increased the release of 14C-PIH from the HSA-containing dialysis sac relative to that found with HSA alone (Fig. 2B). This latter finding suggests these drugs possess common binding sites and inhibit PIH from binding to HSA, or alternatively, Dp44mT and Bp4eT bind at distant sites which may then allosterically influence 14C-PIH-binding. In conclusion, competition experiments revealed that HSA has some common and/or interacting sites for these ligands.

Computational Docking Studies

Molecular docking studies were then performed to further characterize the ligand-binding sites on HSA (Supplementary Fig. 1A-B). Warfarin (Supplementary Fig. 1Ai) and ibuprofen (Supplementary Fig. 1Bi) were also docked and complexed to HSA as relevant controls, considering that their binding to Sudlow's site I and II, respectively, are well established [5]. The best docking poses of warfarin and ibuprofen correctly reproduced the experimental bioactive conformations with a root mean squared deviation of less than 1 Å from that of the ligand pose present in the X-ray structure (PDB code: 2BXD and 2BXG, respectively).

Docking at Sudlow's Site I of HSA

These simulations docked warfarin, Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH at Sudlow's site I of HSA (Supplementary Fig. 1Ai-iv). Both warfarin and PIH made H-bonds with HSA (Supplementary Fig. 1Ai, iv), whereas Dp44mT and Bp4eT predominantly made hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions (Supplementary Fig. 1Aii-iii). The phenyl ring of warfarin resulted in π–π stacking with Phe211 and Trp214 and cation-π interactions with Lys199, which underlie its high binding affinity (Supplementary Fig. 1Ai). The docking of PIH (Supplementary Fig. 1Aiv) showed H-bonds with Tyr150, Arg222, Arg257 and Ala291. The hydrophobic groups of Dp44mT (Supplementary Fig. 1Aii) and Bp4eT (Supplementary Fig. 1Aiii) were favorably enclosed by the hydrophobic regions on HSA. Interestingly, the orientation of Bp4eT was flipped compared to Dp44mT when docked into Sudlow's site I, despite these two ligands having similar structures (Fig. 1A). This effect may due to the formation of a minimum energy conformation by Bp4eT under this pose [46].

As an approximation of the interaction of the ligand with the protein in terms of relative binding affinity, the GlideScore or GScore (GS; or docking score) was calculated from the docking simulations [46]. Docking of the agents at Sudlow's site I demonstrated the following GS order: warfarin (GS = −8.40 kcal/mol) > Bp4eT (GS = −8.15 kcal/mol) > PIH (GS = −8.03 kcal/mol) > Dp44mT (GS = −7.21 kcal/mol). These data suggest Dp44mT has the least affinity for Sudlow's site I. However, the GS indicates that Bp4eT and PIH have a similar affinity for Sudlow's site I. Notably, the GS parameter is an estimate only, and as the GS values are similar for Bp4eT and PIH, it should not be used to rank these ligands in terms of relative binding affinity.

Docking at Sudlow's Site II of HSA

Ibuprofen, Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH were also virtually docked at Sudlow's site II of HSA (Supplementary Fig. 1Bi-iv). In the X-ray structure of HSA and ibuprofen [47], ibuprofen interacts with Arg410, Tyr411 and Lys414 via H-bonds. These interactions were correctly modeled with an additional cation-π interaction between Arg410 and the phenyl ring of ibuprofen (Supplementary Fig. 1Bi). PIH formed H-bonds to Arg410 (2.07 Å) and Tyr411 (2.18 Å) through its hydroxymethyl and hydroxyl groups, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1Biv). The distal parts of the molecule were mainly located in a hydrophobic pocket, in a similar fashion to that of ibuprofen (cf. Supplementary Fig. 1Bi to 1Biv). Interestingly, while Dp44mT and Bp4eT both bind in the same putative binding pocket as PIH, a different ligand orientation was observed. The main interactions were H-bonds formed from the pyridyl nitrogen acceptor to Asn391 and cation-π interactions of the second pyridyl ring with Lys414 (Supplementary Fig. 1Bii-iii).

The GS obtained after docking the ligands at Sudlow's site II demonstrated the following order, namely: ibuprofen (GS = −8.50 kcal/mol) > PIH (GS = −6.0 kcal/mol) > Bp4eT (GS = −5.0 kcal/mol) > Dp44mT (GS = −4.9 kcal/mol). Again, Dp44mT showed the lowest interaction with Sudlow's site II, which was consistent with the lack of effect of this ligand in competition studies performed using equilibrium dialysis experiments (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, PIH showed the highest affinity for Sudlow's site II, relative to Bp4eT and Dp44mT, which was consistent with the dialysis studies assessing competition with ibuprofen (Fig. 2A).

In conclusion, molecular modeling indicated that 14C-PIH binds to HSA at both Sudlow's site I and II, potentially via H-bonds and this was consistent with the competition studies with warfarin and ibuprofen in dialysis experiments (Fig. 2A). Molecular modeling suggested that 14C-Bp4eT may share these HSA-binding sites, although in dialysis studies (Fig. 2A), limited competition was observed with warfarin only, presumably at Sudlow's site I. Dp44mT had the weakest interaction with Sudlow's site I and II, which was in agreement with its lack of effect in competition studies with warfarin and ibuprofen, respectively (Fig. 2A).

HSA Markedly Increases 14C-Dp44mT Uptake, But Decreases 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH Uptake

Considering that: (1) these ligands bind to albumin (Fig. 1B, 2A-B, Supplementary Fig. 1A-B); (2) the high levels of protein accumulation in the tumor interstitium due to the enhanced permeability and retention effect [15-17]; and (3) the potential influence of protein-drug binding on drug bioavailability [7], we examined the cellular targeting and uptake of 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH in the presence and absence of the serum proteins, HSA, BSA or Tf (Fig. 3A-C).

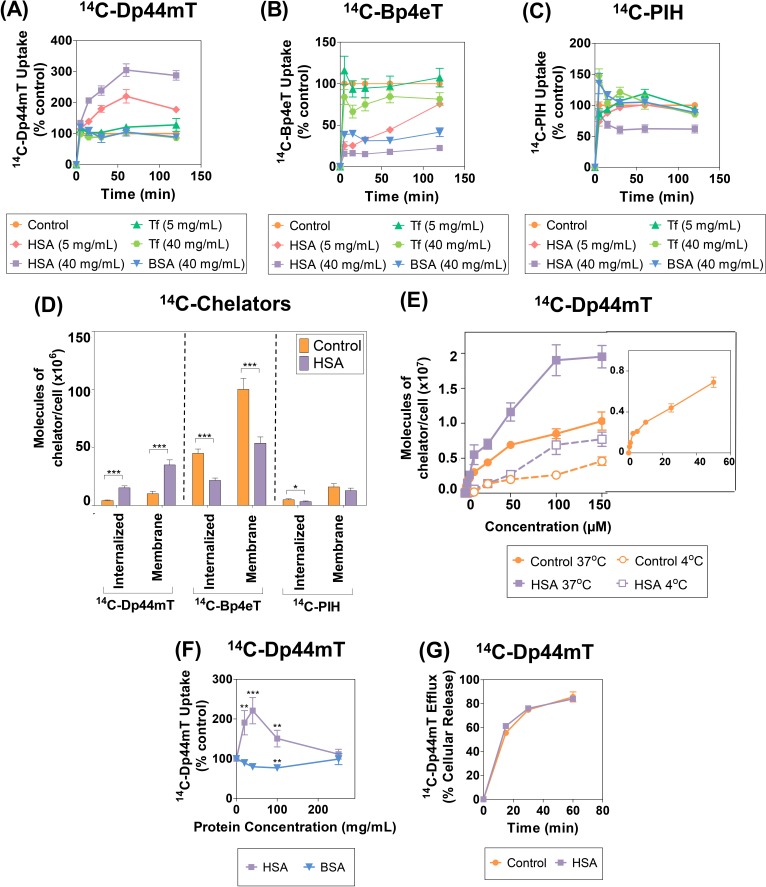

Figure 3. (A-C): Effect of human serum albumin (HSA), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and transferrin (Tf) on the uptake of: (A) 14C-Dp44mT; (B) 14C-Bp4eT; and (C) 14C-PIH by the human SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cell line at 37°C.

The cells were incubated in media containing the 14C-chelator (25 μM) in the presence and absence of HSA (5 or 40 mg/mL), BSA (40 mg/mL) or Tf (5 or 40 mg/mL) for 0-120 min at 37°C. The cells were then placed on ice, washed 4 times using ice-cold PBS, removed from the plates and the radioactivity was quantified. (D) HSA potentiates 14C-Dp44mT uptake in both the membrane and internalized compartments. SK-N-MC cells were incubated with 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT or 14C-PIH (25 μM) with or without HSA (40 mg/mL) for 2 h/37°C, washed in cold PBS, treated with Pronase (1 mg/mL) for 30 min/4°C and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm/1 min. The medium was collected to represent the Pronase-sensitive membrane-bound fraction and the cells were resuspended in PBS to represent the Pronase-insensitive internalized component. Radioactivity was quantified and results were expressed as described above. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001 relative to the corresponding control. (E) Stimulation of HSA uptake of 14C-Dp44mT is saturable. Uptake of 14C-Dp44mT uptake as a function of concentration in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) by SK-N-MC cells at 37°C. SK-N-MC cells were incubated with either HSA (40 mg/mL)-containing media or protein-free media with 14C-Dp44mT (0.1-150 μM) for 2 h at 4°C or 37°C. The cells were then placed on ice, washed 4 times using ice-cold PBS, removed from the plates and the radioactivity quantified. Inset shows the uptake of 14C-Dp44mT (0.1-50 μM) by SK-N-MC cells after a 2 h/37°C incubation. (F) 14C-Dp44mT uptake is competitively inhibited by excess HSA. 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of increasing concentrations of HSA or BSA at 37°C. SK-N-MC cells were incubated in media containing 14C-Dp44mT (25 μM) in the presence or absence of HSA or BSA (20-250 mg/mL) for 2 h/37°C. The remainder of the experiment was performed as described above in Fig. 3F. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001 relative to the control. (G) Efflux of 14C-Dp44mT from SK-N-MC cells. Cells were prelabeled with 14C-Dp44mT (25 μM) for 2 h/37°C in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL), washed 4 times on ice and then reincubated for 0-60 min in medium containing HSA (40 mg/mL) and the release of 14C-Dp44mT assessed. Results are expressed as a percentage of 14C-Dp44mT released (mean ± S.E.M.) of at least 3 experiments.

In these studies, concentrations of apo-Tf and HSA at 5 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL, respectively, were used to approximate their physiological concentrations in human plasma [5, 48]. 14C-Ligand uptake was also assessed relative to Tf at 40 mg/mL, as a direct comparison to HSA at this concentration. Similarly, HSA was used at 5 mg/mL as a comparison to physiological Tf levels (52). To examine species-specific differences in terms of the 14C-ligand interaction with albumin, BSA (40 mg/mL) was chosen as a control protein due to its homology with HSA [5]. Studies were initially performed using SK-N-MC cells that have been well characterized in terms of the uptake and biological activity of these ligands [24, 35, 37, 38].

Interestingly, 14C-Dp44mT uptake was significantly (p<0.001-0.05) increased in the presence of HSA (5 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL) relative to the control (i.e., ligand alone in control media) at all time points examined (Fig. 3A). In contrast, addition of Tf (5 or 40 mg/mL) or BSA (40 mg/mL) led to no significant (p>0.05) alteration in 14C-Dp44mT uptake relative to the control (i.e., protein-free media) after a 15-120 min incubation (Fig. 3A).

In contrast to the observations with 14C-Dp44mT, HSA (5 or 40 mg/mL), Tf (40 mg/mL), or BSA (40 mg/mL), markedly and significantly (p<0.001-0.05) reduced 14C-Bp4eT uptake by cells relative to the control (i.e., ligand alone) at all time points (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, Tf at 5 mg/mL had no significant (p>0.05) effect on 14C-Bp4eT uptake (Fig. 3B). As observed for Bp4eT, 14C-PIH uptake was also significantly (p<0.001-0.05) reduced by HSA (40 mg/mL) after a 15-120 min incubation (Fig. 3C). Moreover, 14C-PIH uptake was slightly (p<0.05) reduced by HSA (5 mg/mL), BSA (40 mg/mL) and Tf (40 mg/mL) after 120 min relative to the control. Conversely, no overall significant (p>0.05) difference was evident for 14C-PIH uptake in Tf- containing media (5 mg/mL) compared to the control (Fig. 3C).

Collectively, the cellular uptake of 14C-Dp44mT was markedly increased by HSA (40 mg/mL), in contrast to Tf or BSA at the same concentration. This observation indicated that HSA, rather than other plasma proteins or albumin from another species, specifically mediated an increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake. Conversely, 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake was reduced by HSA (40 mg/mL). These findings correlate with the appreciable binding affinity of 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH for HSA (Fig. 2A), resulting in a decrease in 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake by SK-N-MC cells. Overall, these results indicate HSA has pronounced differential effects on 14C-ligand uptake despite their structural similarities (Fig. 1A).

Membrane and Internalized Uptake of 14C-Dp44mT by Cells are Increased by HSA, while 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH Uptake are Decreased

To determine if HSA altered the cellular distribution of the 14C-chelators, uptake into the internalized and membrane (non-internalized) fractions were assessed after incubation with the general protease, Pronase, using standard procedures [49-52] (Fig. 3D). HSA significantly (p<0.001) increased internalized and membrane uptake of 14C-Dp44mT by cells relative to the control (Fig. 3D). In contrast, HSA significantly (p<0.001) decreased the internalized and membrane uptake of 14C-Bp4eT compared to the control (Fig. 3D). Similarly, incubation of cells with HSA significantly (p<0.05) decreased internalized 14C-PIH uptake, while membrane uptake of 14C-PIH was only slightly reduced (p>0.05). Collectively, HSA increased the internalized and membrane uptake of 14C-Dp44mT, while decreasing the internalized and membrane uptake of 14C-Bp4eT and to a slightly lesser extent 14C-PIH (Fig. 3D).

HSA Markedly Increases 14C-Dp44mT Uptake as a Function of Temperature and Ligand Concentration

To elucidate the mechanism involved in HSA-potentiated 14C-Dp44mT uptake, the temperature dependence of this process over a concentration range (0.1-150 μM) was examined during a 2 h incubation at 4°C or 37°C in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) using SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 3E). In the absence of HSA, 14C-Dp44mT uptake at 37°C saturated at approximately 5-10 μM (see inset Fig. 3E), as reported previously, suggesting the presence of a putative Dp44mT receptor/carrier [34]. The addition of HSA significantly (p<0.001-0.01) increased 14C-Dp44mT uptake at 37°C at ligand concentrations greater than ≥25 μM (Fig. 3E). Saturation of the HSA-stimulated uptake mechanism occurred at a Dp44mT concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 3E). These two saturation events suggest two different Dp44mT-binding sites in the presence or absence of HSA.

Examining 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA using non-linear regression analysis demonstrated a high correlation (r2 = 0.97) and resulted in a Bmax value of 2.92 ± 0.12 × 107 molecules/cell (n = 9) and a Kd value of 65 ± 6 μM (n = 9). In the absence of HSA, non-linear regression also indicated a high correlation (r2 = 0.96), but resulted in a lower Bmax value of 1.20 ± 0.04 × 107 molecules/cell (n = 9) and a lesser Kd value of 33 ± 3 μM (n = 9). Of relevance, in a previous study using SK-N-MC cells under different experimental conditions, a higher Bmax value (4.28 × 107 molecules of chelator/cell) and a lower Kd value (2.45 μM) were observed for Dp44mT uptake in the absence of HSA [34]. These dissimilar results are probably due to the presence of 10% (v/v) FCS in the earlier study [34], which is known to affect cellular metabolism, receptor dynamics and expression [49, 50, 53].

As demonstrated previously in the absence of HSA [34], 14C-Dp44mT uptake as a function of concentration was temperature-dependent, with a significant (p<0.001) decrease in cellular 14C-Dp44mT uptake being observed at 4°C relative to 37°C at all concentrations (Fig. 3E). At 37°C, the cell is metabolically active and results in receptor recycling [51, 54, 55]. Thus, the 14C-ligand can label receptors at both the plasma membrane and those cycling intracellularly [51, 54, 55]. In contrast, at 4°C, cells are metabolically inactive, inhibiting receptor cycling. Thus, only plasma membrane-bound receptors are labeled with the ligand, leading to a decrease in uptake relative to that found at 37°C [51, 54, 55].

Notably, 14C-Dp44mT uptake as a function of concentration in the presence of HSA was also temperature-dependent. In fact, a significant (p<0.001-0.01) decrease in 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA was observed at 4°C relative to 37°C at all Dp44mT concentrations (Fig. 3E). The saturable and temperature-dependent nature of 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA suggested a mechanism consistent with a carrier/receptor-mediated uptake process.

Excess Non-Physiological Levels of Unlabeled HSA Decrease Dp44mT Uptake by Cells

Next, the effect of increasing HSA and BSA concentrations (20-250 mg/mL) on 14C-Dp44mT uptake by SK-N-MC cells was examined after 2 h/37°C (Fig. 3F). These studies were performed to determine the ability of excess HSA levels to compete with and inhibit the enhanced HSA-mediated uptake of 14C-Dp44mT. Furthermore, considering BSA (40 mg/mL) did not increase 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 3A), relevant control studies were also performed using the same concentrations of BSA (20-250 mg/mL; Fig. 3F).

As evident in Fig. 3A, BSA did not significantly (p>0.05) increase 14C-Dp44mT uptake at all concentrations tested (Fig. 3F). In fact, BSA (100 mg/mL) significantly (p<0.01) decreased 14C-Dp44mT uptake to 77 ± 4% of the control (i.e., 14C-Dp44mT in the absence of protein; Fig. 3F). In contrast, as observed in Fig. 3A and E, 14C-Dp44mT uptake was significantly (p<0.001-0.01) increased in the presence of HSA (20-100 mg/mL) relative to the control (i.e., 14C-Dp44mT in the absence of protein; Fig. 3F). However, after the pronounced increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake up to the physiological HSA concentration in plasma (40 mg/mL), 14C-Dp44mT uptake then decreased as the HSA concentration increased up to 100 and 250 mg/mL (Fig. 3F). In fact, at this latter HSA concentration, a marked and significant (p<0.01) decrease in 14C-Dp44mT uptake was observed in comparison to physiological HSA levels (40 mg/mL; Fig. 3F). Thus, it can be speculated that the decrease in 14C-Dp44mT uptake at higher HSA concentrations relative to physiological levels may be due to the ability of excess HSA to compete with 14C-Dp44mT-bound HSA for the cellular HSA-binding site.

Effect of HSA on 14C-Dp44mT Efflux from Cells

We also investigated the effect of HSA on efflux of 14C-Dp44mT (Fig. 3G), as the stimulatory effects of HSA on intracellular uptake of 14C-Dp44mT (Fig. 3D) could also be due to its effect on the release of the ligand from the cell. For example, decreased efflux of 14C-Dp44mT from cells in the presence of HSA could lead to cellular accumulation of the ligand. To assess this hypothesis, SK-N-MC cells were pre-labeled with 14C-Dp44mT (25 μM) in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) for 2 h at 37°C. To replicate physiological conditions, the cellular efflux of 14C-Dp44mT was then assessed in the presence of HSA (40 mg/mL) as a function of time (0-60 min) at 37°C.

The cellular release of 14C-Dp44mT increased with time and reached a plateau at 30 min, where 74.8 ± 2.3% of 14C-Dp44mT was released (Fig. 3G). Importantly, the pre-labeling of cells with 14C-Dp44mT in the presence of HSA did not significantly (p>0.05) alter the efflux of 14C-Dp44mT at all time points (Fig. 3G). Performing the efflux incubation in the absence of HSA also demonstrated no difference in 14C-Dp44mT release when cells were labeled in the presence or absence of HSA (data not shown). In summary, these data indicate that other factors, besides the efflux of the ligand, were responsible for the enhanced cellular uptake of 14C-Dp44mT in the presence of HSA.

The Increase in 14C-Dp44mT Uptake Mediated by HSA is Observed in a Variety of Neoplastic and Normal Cell-Types

To understand if the increase of 14C-Dp44mT uptake or inhibition of 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake mediated by HSA were specific to certain cell-types, 14C-chelator uptake in the presence and absence of HSA was examined using a range of cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A-C). The uptake of the 14C-chelators was examined in a variety of immortal cancer/transformed cell-types (i.e., SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma, SK-Mel-28 melanoma, MCF-7 breast cancer, DMS-53 lung carcinoma, HepG2 hepatoma, HK-2 immortalized kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells) and normal, mortal cells (i.e., HUVECs and MRC-5 fibroblasts) in HSA-containing (40 mg/mL) or protein-free media for 2 h/37°C (Supplementary Fig. 2A-C).

As evident in Fig. 3A, in SK-N-MC cells, 14C-Dp44mT uptake was significantly (p<0.01) increased by HSA to 300 ± 10% of the control (i.e., ligand without HSA; Supplementary Fig. 2A). Additionally, HSA also significantly (p<0.01-0.001) increased 14C-Dp44mT uptake in SK-Mel-28, MCF-7, HUVEC and DMS-53 cells to 169-372% of the control, demonstrating that this effect was not specific to SK-N-MC cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Interestingly, HSA did not significantly (p>0.05) increase uptake of 14C-Dp44mT in MRC-5, HepG2 and HK-2 cells compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. 2A). In fact, HSA slightly, but significantly (p<0.01), decreased 14C-Dp44mT uptake by HK-2 cells versus the control (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

In contrast to 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT uptake was significantly (p<0.01-0.001) decreased in the presence of HSA (40 mg/mL) in all cell-types studied (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Similarly to 14C-Bp4eT, 14C-PIH uptake was also significantly (p<0.01-0.05) inhibited in the presence of HSA (40 mg/mL) in all cell-types examined, except for DMS-53, MRC-5 and HK-2 cells, where a non-significant (p>0.05) decrease was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Hence, in contrast to 14C-Dp44mT, these results indicated that the ability of HSA to inhibit 14C-Bp4eT or 14C-PIH uptake was independent of the cell-type assessed.

Collectively, these studies demonstrated that the HSA-mediated increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake and decrease in 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake was observed in a variety of normal and neoplastic cell-types. Considering this, albumin receptors/binding sites have been previously reported in a variety of cell-types [36]. Hence, we examined the expression of five known albumin receptors/binding proteins, namely: calreticulin [56], hnRNP [56], cubilin [57], SPARC [58] and FcRn [59] in the immortal and normal/mortal cell lines assessed above. However, no direct correlation was observed between the expression of these proteins (data not shown) and HSA-mediated 14C-Dp44mT uptake by these cell-types (Supplementary Fig. 2A). This observation suggested that HSA-mediated Dp44mT uptake was independent of these albumin-binding proteins.

HSA Specifically Binds to Cells, but Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH, do not Affect 125I-Labeled HSA Uptake

To further elucidate the mechanisms behind the potentiation of 14C-Dp44mT targeting by HSA, the cellular uptake of 125I-labeled HSA by SK-N-MC cells was examined in the presence and absence of unlabeled Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH (25 μM; Fig. 4A-B). It was hypothesized that cellular stress induced by Dp44mT may increase 125I-HSA-mediated uptake, and thus, potentiate the transport of the chelator into the cell. In these studies, the uptake of 125I-HSA (0.001-10 mg/mL) was performed as a function of concentration after a 2 h/37°C incubation with SK-N-MC cells in the presence and absence of Dp44mT (Fig. 4A).

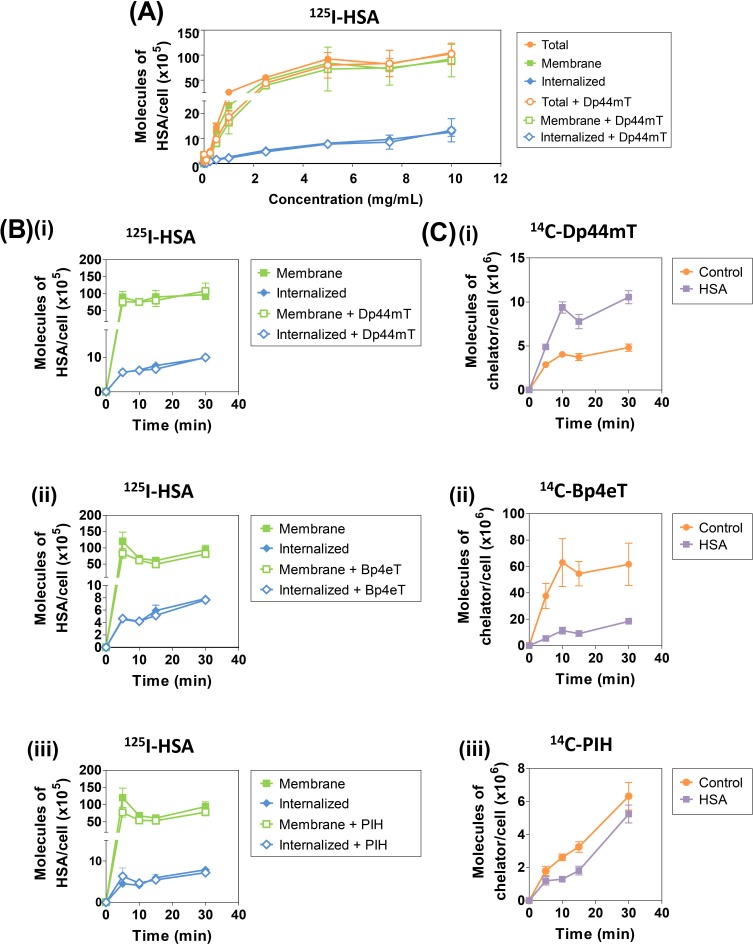

Figure 4. (A) Dp44mT has no effect on the uptake of 125I-HSA by human SK-N-MC cells as a function of concentration at 37°C.

SK-N-MC cells were incubated in media with 125I-HSA (0.001-10 mg/mL) in the presence and absence of unlabeled Dp44mT (25 μM) for 2 h/37°C. Cells were washed in cold PBS, treated with Pronase (1 mg/mL) for 30 min/4°C and radioactivity of the resulting Pronase-sensitive (membrane-bound) fraction and the Pronase-insensitive (cellular fraction) was assessed. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. from 3 experiments. (B) Effect of unlabeled (i) Dp44mT, (ii) Bp4eT, or (iii) PIH on the uptake of 125I-HSA by SK-N-MC cells as a function of time at 37°C. SK-N-MC cells were incubated with 125I-HSA (7.5 mg/mL) with or without unlabeled Dp44mT, Bp4eT, or PIH (25 μM) for 30 min/37°C. Subsequent steps were performed as above. (C) Effect of HSA (7.5 mg/mL) on (i) 14C-Dp44mT, (ii) 14C-Bp4eT or (iii) 14C-PIH (25 μM) uptake by SK-N-MC cells as a function of time at 37°C. Experiments were performed in parallel to those in Figure 6B, with the methodology being the same as that described in Figure 4A-C.

The total uptake of 125I-HSA by SK-N-MC cells plateaued at approximately 5-7.5 mg/mL and occurred by a single exponential process, suggesting a saturable binding site (Bmax: 1.46 ± 0.10 × 107 molecules/cell; Kd: 62 ± 11 μM; Fig. 4A). Of note, previous studies have identified Kd values for albumin-binding sites in the micomolar range (0.25 - 15.1 μM) in other cell-types [60, 61]. The internalized (Pronase-insensitive) and membrane (Pronase-sensitive) uptake of 125I-HSA also increased as a function of 125I-HSA concentration and again plateaued at approximately 5-7.5 mg/mL (Fig. 4A). These observations suggested a saturable membrane-binding site which became internalized, potentially by a process of receptor-mediated endocytosis, which has been described previously for HSA receptors [36, 62, 63]. Notably, only a fraction of 125I-HSA (7.5 mg/mL) was internalized, with approximately 90% remaining membrane-bound (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the internalized or membrane-bound 125I-HSA uptake was not significantly (p>0.05) altered in the presence of Dp44mT (Fig. 4A).

To further elucidate the differential effects of HSA on ligand uptake, 125I-HSA (7.5 mg/mL) uptake was examined in the presence of unlabeled Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH (25 μM) as a function of time (5-30 min; Fig. 4Bi-iii). This concentration of HSA was utilized as uptake became clearly saturated at this concentration (Fig. 4A). In parallel with these studies, the uptake of 14C-Dp44mT, 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH (25 μM) was performed as a function of time (5-30 min) in the presence or absence of HSA (7.5 mg/mL) to assess the effect of this protein on 14C-chelator uptake (Fig. 4Ci-iii). Irrespective of the presence or absence of the ligands, HSA uptake was biphasic, consisting of a rapid increase in internalized (Pronase-insensitive) and membrane-bound (Pronase-sensitive) 125I-HSA uptake followed by a plateau after 5 min of incubation (Fig. 4Bi-iii). These kinetics are consistent with the initial binding of 125I-HSA to its receptor, uptake by endocytosis, followed by release of the ligand by exocytosis, as described for other plasma proteins in other neoplastic cell-types [50]. As found for 125I-HSA uptake as function of concentration (Fig. 4A), membrane-bound 125I-HSA was markedly greater than the internalized 125I-HSA uptake, with approximately 10% of the total 125I-HSA being internalized (8.5 × 106 molecules of HSA/cell; Fig. 4Bi-iii). The internalized or membrane-bound 125I-HSA uptake was not significantly (p>0.05) altered in the presence of Dp44mT, Bp4eT, or PIH (Fig. 4Bi-iii).

As shown previously (Fig. 3A), 14C-Dp44mT uptake was significantly (p<0.001) increased in the presence of unlabeled HSA (7.5 mg/mL) at all time points examined (Fig. 4Ci). Moreover, as evident in Fig. 3B and C, unlabeled HSA significantly (p<0.05) decreased 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake relative to the control (Fig. 4Cii-iii). Collectively, these studies demonstrated the altered uptake of the 14C-chelators in the presence of HSA was not due to altered HSA uptake.

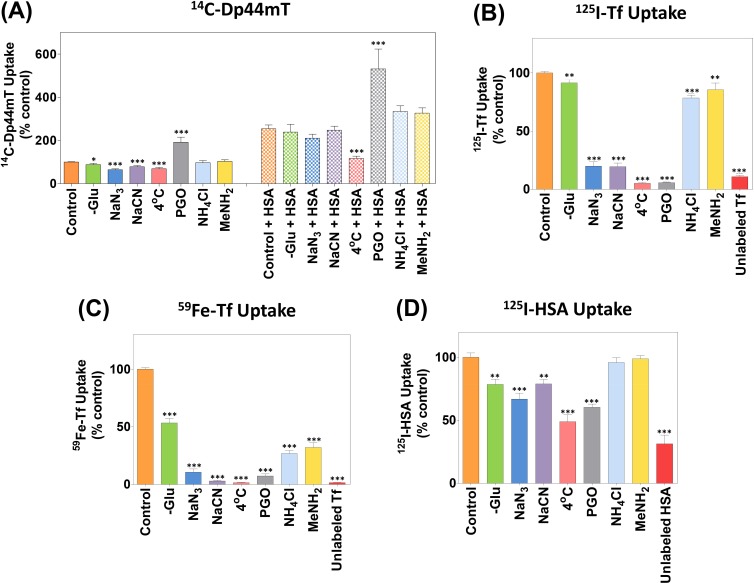

Effect of Glucose-Deprivation, Metabolic and Endocytosis Inhibitors, Temperature and Lysosomotropic Agents on Dp44mT Uptake in the Presence and Absence of HSA

To differentiate between the cellular mechanisms involved in 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence and absence of HSA, a series of conditions were utilized examining: (1) glucose-deprivation and several well characterized metabolic inhibitors [34, 35]; (2) incubation temperature; (3) an endocytosis inhibitor [64-67]; (4) and lysosomotropic agents [52, 65, 68]. The effects of these agents on 14C-Dp44mT uptake were compared to parallel experiments examining uptake of 125I-HSA or the positive control, 59Fe-125I-Tf. This comparison was performed as 59Fe-125I-Tf is well known to be internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis in SK-N-MC cells and many other cell-types [52, 69-71]. In terms of 59Fe-125I-Tf uptake, we have assessed both 59Fe bound to the specific binding sites of the protein (59Fe-Tf), as well as the protein itself (125I-Tf; [52, 69-71]).

(1) Effect of Glucose-Deprivation and Metabolic Inhibitors on 14C-Dp44mT Uptake

We previously demonstrated that 14C-Dp44mT uptake by SK-N-MC cells was dependent on ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation in the absence of HSA, as they could be partly inhibited using the metabolic inhibitors, sodium azide (30 mM), or sodium cyanide (5 mM) [34], which inhibit complex IV of the mitochondrial electron transport chain [72]. In this investigation, the same protocol was used as described in [34], in which cells were preincubated with inhibitors for 30 min/37°C, followed by the addition of 14C-Dp44mT or 14C-Dp44mT and HSA to these solutions, which were then incubated with the cells for 1 h/37°C. We previously demonstrated that these same incubation conditions with inhibitors markedly suppressed cellular ATP levels [34] that are vital for many cellular processes e.g., endocytosis [52, 70, 73].

Incubation of cells in the absence of glucose (−Glu) led to a slight, but significant (p<0.05) decrease in 14C-Dp44mT uptake relative to cells incubated with glucose-containing medium (i.e., control; Fig. 5A). Similarly to previous studies examining 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the absence of HSA [34], herein we also show that in glucose-free medium containing sodium azide or sodium cyanide, 14C-Dp44mT uptake was significantly (p<0.001) reduced to 65 ± 4% and 78 ± 6%, respectively, relative to glucose-containing control medium (Fig. 5A). In contrast, no significant (p>0.05) difference in 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA versus the control was shown using glucose-free medium (−Glu) or these inhibitors (Fig. 5A). These data suggest HSA-mediated 14C-Dp44mT uptake was less reliant on metabolic energy relative to 14C-Dp44mT uptake alone.

Figure 5. The effect of metabolic and endocytosis inhibitors, temperature, lysosomotropic agents or a 100-fold excess of protein on the uptake of 14C-Dp44mT in the presence and absence of HSA, or 59Fe-125I-Tf or 125I-HSA uptake.

SK-N-MC cells were pre-incubated with: (1) FCS-free media; (2) FCS- and glucose-free media (−Glu); (3) FCS- and Glu-free media containing the known metabolic inhibitors sodium azide (30 mM) or sodium cyanide (5 mM); (4) FCS-free media at 4°C; (5) FCS-free media containing the endocytosis inhibitor, phenylglyoxal (PGO; 5 mM); (6) FCS-free media containing the lysosomotropic agents, ammonium chloride (15 mM) or methylamine (15 mM); or (7) 100-fold excess unlabeled Fe-Tf or HSA (75 μM) for 30 min at 37°C unless otherwise stated. Following this, the uptake of (A) 14C-Dp44mT (25 μM) in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL), (B-C) 59Fe-125I-Tf (0.75 μM) or (D) 125I-HSA (0.75 μM) by cells was assessed under the continuation of these 7 incubation conditions for 1 h. The cells were then washed and processed for quantification. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (3 experiments). *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001 relative to the corresponding control.

(2) Effect Incubation Temperature on 14C-Dp44mT Uptake

Additional studies demonstrated that 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the absence of HSA was significantly (p<0.001) reduced at 4°C relative to 37°C (Fig. 5A). A similar and significant (p<0.001) inhibitory effect of incubation at 4°C was also observed on HSA-mediated 14C-Dp44mT uptake relative to uptake observed at 37°C (Fig. 5A). Hence, 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence and absence of HSA was dependent on incubation temperature.

(3 & 4) Effect of an Endocytosis Inhibitor and Lysosomotropic Agents on 14C-Dp44mT Uptake

Experiments then assessed the role of endocytosis and endosomal/lysosomal acidification on 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence and absence of HSA. In these studies, the well-characterized endo-/exocytosis inhibitor, phenylglyoxal (PGO; 5 mM; [64-66]), or the well known lysosomotropic agents, ammonium chloride (15 mM) or methylamine (15 mM), were assessed [52, 65, 68]. After incubation with PGO, there was a significant (p<0.001) increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake relative to the control in the presence or absence of HSA (Fig. 5A). Considering that PGO inhibits both endocytosis and exocytosis [64-66], it can be speculated that the PGO-enhanced accumulation of 14C-Dp44mT was due to the inhibition of exocytosis, thereby preventing efflux of this ligand.

In contrast, both lysosomotropic agents had no significant (p>0.05) effect on 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence or absence of HSA relative to the control (Fig. 5A). Considering the failure of PGO and lysosomotropic agents to inhibit 14C-Dp44mT uptake with or without HSA, and the fact that they significantly (p<0.001-0.01) inhibit 59Fe- and 125I-Tf uptake from 59Fe-125I-Tf (see Fig. 5B, C), these data suggest that 14C-Dp44mT uptake was independent of endocytosis and the acidification of the endosomal/lysosomal compartment.

Effect of Glucose-Deprivation, Metabolic and Endocytosis Inhibitors, Temperature and Lysosomotropic Agents on 59Fe-125I-Transferrin and 125I-HSA Uptake

In parallel studies implementing the same incubation conditions as the 14C-Dp44mT uptake experiments (Fig. 5A), the cellular uptake of 59Fe-125I-Tf (0.75 μM; Fig. 5B-C) or 125I-HSA (0.75 μM; Fig. 5D) were investigated, as uptake of these proteins are well characterized [52, 65, 70, 73]. The uptake of 59Fe-125I-Tf and 125I-HSA by cells was significantly (p<0.001-0.01) inhibited in the absence of glucose relative to media containing glucose (control; Fig. 5B-D). This effect of glucose-free medium was generally potentiated in the presence of sodium azide and sodium cyanide, decreasing 59Fe-Tf, 125I-Tf and 125I-HSA uptake to 4-14%, 23-24% and 67-79% of the control, respectively (Fig. 5B-D). Hence, similarly to 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 5A), 59Fe-125I-Tf and 125I-HSA uptake was dependent on mitochondrial electron transport chain activity (Fig. 5B-D). In contrast, this was markedly different to 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA (Fig. 5A), that was independent of the inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport chain.

Cells incubated at 4°C internalized significantly (p<0.001) less 59Fe-Tf, 125I-Tf, or 125I-HSA than those incubated at 37°C (Fig. 5B-D). Incubation of cells with the endo-/exocytosis inhibitor, PGO, or the lysosomotropic agents, ammonium chloride or methylamine, markedly and significantly (p<0.001-0.01) inhibited 125I-Tf (Fig. 5B) and 59Fe-Tf uptake (Fig. 5C). Similarly, the uptake of 125I-HSA was significantly (p<0.001) inhibited in the presence of PGO (Fig. 5D). This observation suggests that 14C-Dp44mT enters cells independently of 125I-HSA, as 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence or absence of HSA was significantly (p<0.001) increased upon incubation with PGO (Fig. 1A). In contrast to 59Fe-Tf or 125I-Tf uptake, 125I-HSA uptake was not significantly (p>0.05) altered in the presence of the lysosomotropic agents, ammonium chloride or methylamine (Fig. 5D). Importantly, 59Fe-Tf, 125I-Tf, or 125I-HSA uptake was significantly (p<0.001) inhibited upon the addition of a 100-fold excess of the unlabeled protein, namely Fe-Tf or HSA, respectively (Fig. 5B-D), suggesting competition between the unlabeled and labeled protein for the same binding sites. These results agree with previous studies demonstrating 59Fe-Tf, 125I-Tf and 125I-HSA uptake occur via energy- and temperature-sensitive endocytosis [69, 70, 74, 75].

Together, these data indicate in contrast to 59Fe-Tf, 125I-Tf and 125I-HSA uptake by cells, 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA was insensitive to glucose levels, inhibition of energy metabolism and the suppressive effects of lysosomotropic agents or an endo-/exocytosis inhibitor. These observations suggested the HSA-stimulated mechanism of 14C-Dp44mT uptake occurred by a different pathway to the uptake of either 125I-HSA or 59Fe-125I-Tf that occur by endocytosis or endocytosis requiring endosomal acidification, respectively [52, 69-71, 74, 75].

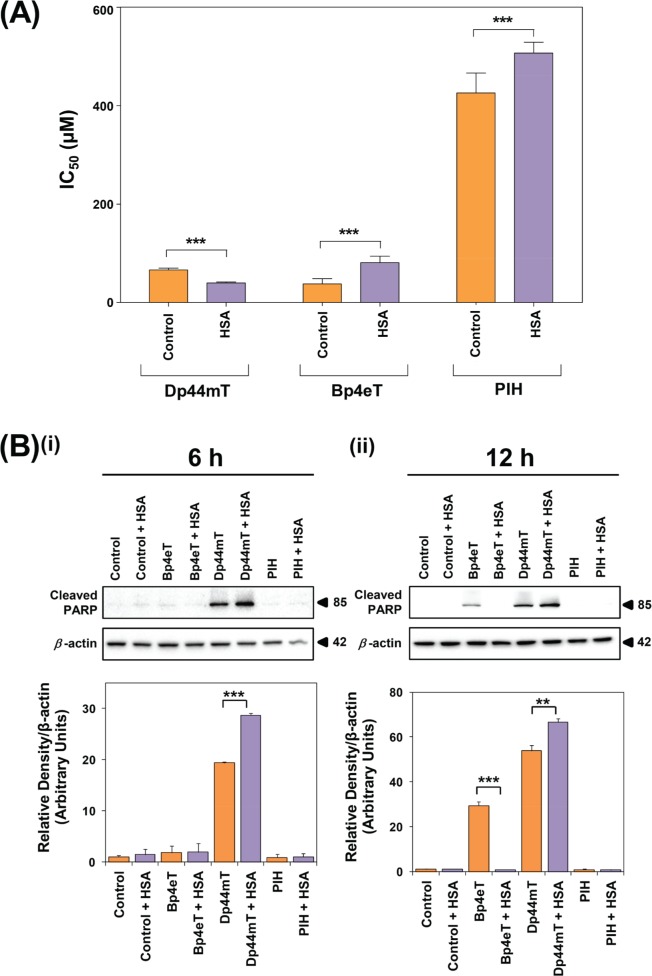

HSA Enhances the Anti-Proliferative Activity of Dp44mT and Inhibits that of Bp4eT and PIH

Considering the increased uptake of 14C-Dp44mT in the presence of HSA (Fig. 3A, D, E), the effect of HSA on the anti-proliferative activity of Dp44mT was examined in SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 6A). Additionally, the effect of HSA on the anti-proliferative activity of Bp4eT and PIH were also assessed (Fig. 6A), considering the inhibitory effects of HSA on 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake (Fig. 3B-C). In these experiments, cells were incubated with Dp44mT (30-120 μM), Bp4eT (30-120 μM), PIH (150-600 μM) or the vehicle alone (control) in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) for 24 h/37°C (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. The effect of HSA on the anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity of Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH.

(A) The anti-proliferative activity of Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH in the presence of HSA for 24 h/37°C. Cells were incubated with Dp44mT (30-120 μM), Bp4eT (30-120 μM), PIH (150-600 μM) or vehicle alone (control) in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) for 24 h/37°C. Trypan blue was used to obtain direct cell counts and to determine IC50 values. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (3 experiments). ***, p<0.001 relative to the corresponding control. (B) Levels of cleaved PARP following treatment of SK-N-MC cells with Bp4eT, Dp44mT or PIH (50 μM) in the presence and absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) after (i) 6 h or (ii) 12 h/37°C. Western blots are typical of 3 independent experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (3 experiments). **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

HSA significantly (p<0.001) increased the anti-proliferative activity of Dp44mT relative to Dp44mT alone, leading to a decrease in its IC50 (Fig. 6A). In fact, after a 24 h incubation, HSA decreased the IC50 of Dp44mT by ≈ 1.6-fold to 40 ± 2 μM in comparison to Dp44mT alone (66 ± 4 μM; Fig. 6A). As an additional control, the anti-proliferative activity of Dp44mT was also examined in the presence of BSA (40 mg/mL; data not shown). However, the IC50 of Dp44mT was not significantly (p>0.05) altered in the presence of BSA (IC50: 72 ± 2 μM) relative to the ligand alone. This observation is in agreement with our studies showing that BSA did not significantly (p>0.05) alter cellular 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 3A).

In contrast to Dp44mT, the anti-proliferative activity of Bp4eT was significantly (p<0.001) reduced by HSA, leading to an increase in the IC50 (81 ± 4 μM) relative to its activity in the absence of HSA (IC50: 38 ± 3 μM; Fig. 6A). Similarly, HSA significantly (p<0.001) increased the IC50 of PIH to 507 ± 7 μM compared to the ligand alone (IC50: 426 ± 14 μM; Fig. 6A). These data are in good agreement with our 14C-chelator uptake experiments and indicate that the HSA-mediated increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 3A) results in its enhanced anti-proliferative efficacy (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the ability of HSA to decrease cellular 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake (Fig. 3B-C) decreased anti-proliferative activity of both ligands (Fig. 6A).

HSA Enhances the Apoptotic Activity of Dp44mT and Inhibits that of Bp4eT

In contrast to PIH and Bp4eT, the cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of Dp44mT was enhanced in the presence of HSA (Figs. 3A, B, 6A). Thus, it was important to examine the effects of HSA on the ability of these ligands to induce apoptosis. In order to do this, the effects of Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH (50 μM) on the levels of the apoptotic marker, cleaved poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP; [76, 77]), were examined in SK-N-MC cells after a 6 or 12 h incubation at 37°C in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL; Fig. 6B).

After a 6 h incubation, Dp44mT resulted in a 19.4-fold increase in cleaved PARP levels relative to the control (Fig. 6Bi). This observation was in good agreement with the known ability of Dp44mT to induce apoptosis in vitro and in vivo [25, 78, 79]. The level of cleaved PARP upon co-incubation of Dp44mT and HSA for 6 h was significantly (p<0.001) increased relative to both the control and Dp44mT treatment alone (Fig. 6Bi). In fact, cleaved PARP levels were 1.3-fold greater in Dp44mT + HSA treated cells relative to Dp44mT alone. These results suggest HSA enhanced the ability of Dp44mT to induce apoptosis at this early time point. In contrast, a 6 h incubation with Bp4eT or PIH in the presence or absence of HSA did not result in significantly (p>0.05) increased cleaved PARP relative to their controls (Fig. 6Bi).

At the 12 h time point, Dp44mT alone and Dp44mT + HSA significantly (p<0.001) increased cleaved PARP relative to their controls (i.e., control medium and control medium + HSA, respectively; Fig. 6Bii). Cleaved PARP levels in cells co-treated with Dp44mT + HSA showed a significant (p<0.01) 1.2-fold increase relative to cells treated with Dp44mT alone. Cells treated with Bp4eT alone demonstrated significantly (p<0.001) increased cleaved PARP relative to the control (Fig. 6Bii). However, this effect was abolished upon incubating cells with Bp4eT in the presence of HSA, resulting in cleaved PARP levels that were significantly (p<0.001) decreased relative to Bp4eT alone and was comparable to the control (Fig. 6Bii). Thus, HSA inhibited the ability of Bp4eT to induce cleaved PARP. In contrast, cells incubated for 12 h with PIH in the presence or absence of HSA did not result in cleaved PARP and were comparable to their controls (Fig. 6Bii).

Collectively, these results demonstrated that HSA was able to significantly (p<0.001-0.01) enhance the apoptotic effects of Dp44mT at 6 and 12 h and this reflected its increased cellular uptake (Fig. 3A, D, E) and anti-proliferative activity (Fig. 6A) of Dp44mT upon HSA co-treatment. In contrast, the presence of HSA was able to inhibit the apoptotic activity of Bp4eT after 12 h, which probably results from the decreased 14C-Bp4eT uptake observed upon incubation with HSA (Fig. 3B, D). On the other hand, PIH did not induce marked levels of PARP cleavage and this reflects the poor anti-proliferative activity of this agent [37] relative to Dp44mT [24, 25] and Bp4eT [38] (Fig. 6A).

DISCUSSION

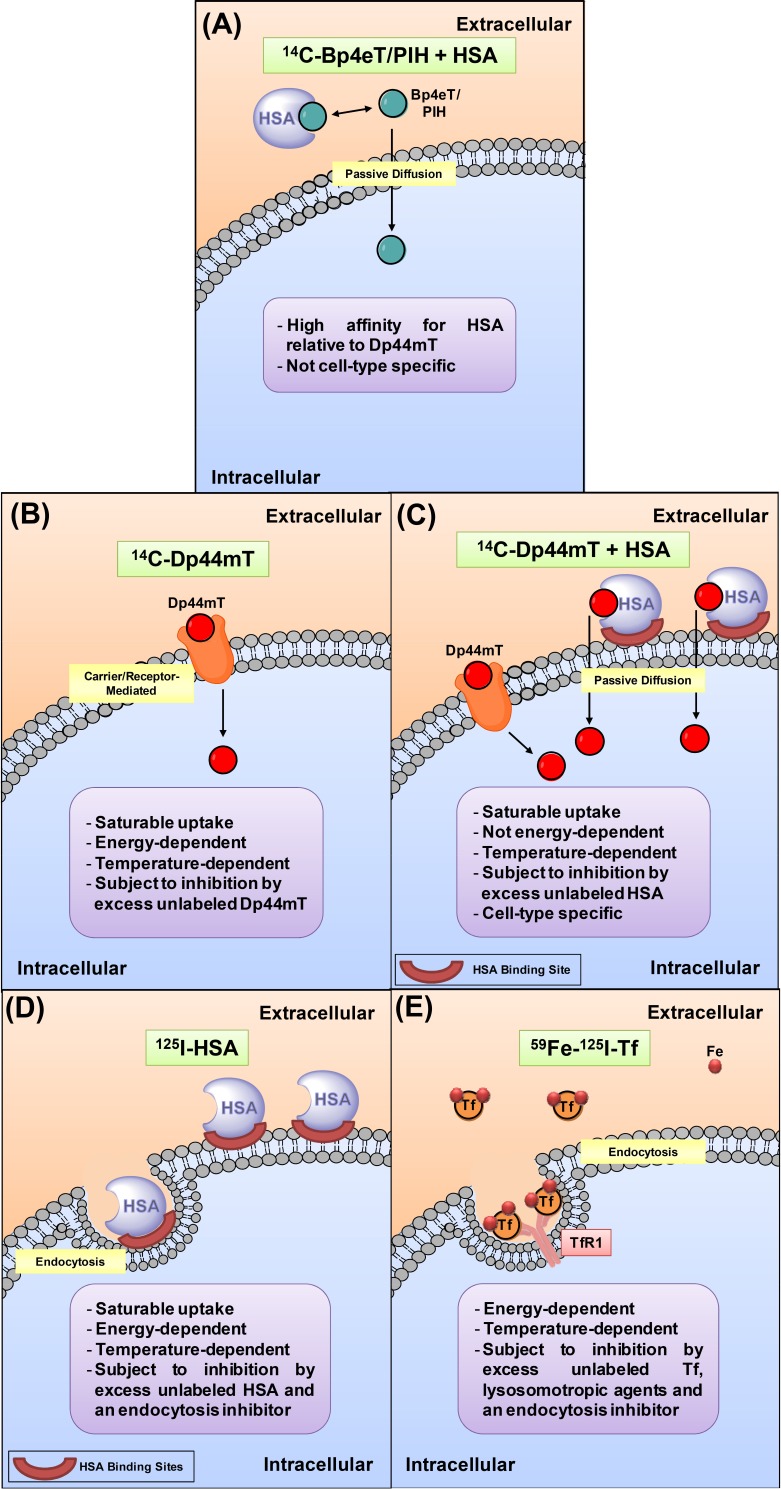

Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH Bind to HSA

In this investigation, studies were performed to determine whether Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH were able to directly bind to albumin using fluorescence spectroscopy and equilibrium dialysis studies. These experiments demonstrated that all the ligands bind to HSA, although with different avidities (Fig. 1-2). In fact, equilibrium dialysis experiments indicated that 14C-Bp4eT became bound to HSA with similar avidity to 14C-PIH, while 14C-Dp44mT was most weakly bound to the protein (Fig. 2A). Molecular docking studies also supported these conclusions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Importantly, these findings indicating the avid binding of Bp4eT and PIH to HSA could explain the decreased uptake of these agents by cells in the presence of this protein (Fig. 3B-D). In fact, in the absence of HSA, Bp4eT and PIH are known to enter cells via passive diffusion [35]. Considering this, HSA may act as an extracellular ‘sink’, preventing the passive diffusion of Bp4eT and PIH into cells (Fig. 7A). Consequently, HSA did not enhance 14C-Bp4eT or 14C-PIH uptake or anti-proliferative activity, but conversely, decreased it (Fig. 3B-D, 7A).

Figure 7. Schematic showing the internalization of 14C-Bp4eT/PIH or 14C-Dp44mT with or without HSA, 125I-HSA or 59Fe-125I-Tf into the cell.

(A) 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH are transported by diffusion in the absence of HSA [34]. In the presence of HSA, HSA-binding inhibits the uptake of 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH, irrespective of the cell-type. This is due to the high affinity of Bp4eT or PIH for HSA, relative to Dp44mT, reducing the levels of free drug available to diffuse into cells. (B) A different mechanism is demonstrated by the structurally similar ligand, Dp44mT. 14C-Dp44mT is taken up by cells via a receptor/carrier in the absence of HSA. This uptake process is saturable, energy- and temperature-dependent and subject to inhibition by excess unlabeled Dp44mT [34]. (C) In the presence of HSA, 14C-Dp44mT uptake occurs through a second, high capacity, saturable process that is cell-type specific and inhibited in the presence of excess unlabeled HSA. This process may be facilitated by: (i) a specific HSA-binding site; (ii) the fact most cellular HSA is bound to the cell membrane (rather than internalized); and (iii) the relatively low affinity of Dp44mT for HSA. These three properties facilitate Dp44mT delivery to cells and create a concentration gradient at the cell surface to enable enhanced uptake via dissociation and passive diffusion. The enhanced delivery of 14C-Dp44mT by HSA increases apoptosis and cytotoxicity. (D) 125I-HSA uptake by cells was saturable, temperature-dependent, inhibited by excess unlabeled HSA, and sensitive to glucose starvation and inhibitors of energy metabolism or endocytosis. Hence, this process was consistent with HSA endocytosis that is known to occur [74, 92]. (E) 59Fe-125I-Tf uptake occurs following the binding to its receptor, Tf receptor 1 (TfR1). This process was temperature- and energy-dependent, and subject to inhibition by excess unlabeled Tf, an endocytosis inhibitor, and in addition, lysosomotropic agents. Hence, 59Fe-125I-Tf uptake occurs through the well characterized process of receptor-mediated endocytosis that requires endosomal acidification [52, 68, 71, 93].

14C-Dp44mT Uptake is Specifically Enhanced by HSA

In contrast to Bp4eT and PIH (Fig. 3B-C), Dp44mT uptake is markedly increased in the presence of physiological concentrations of HSA in the plasma (40 mg/mL) as a function of time (Fig. 3A) and concentration (Fig. 3E). In comparison, HSA markedly decreased 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake (Fig. 3B-C). The enhanced 14C-Dp44mT uptake was specific for HSA and this observation was supported by two findings. First, this effect did not occur in the presence of the same concentration of Tf, suggesting a specific interaction between Dp44mT and HSA and not other plasma proteins (Fig. 3A). Second, stimulation of Dp44mT uptake did not occur with albumin from another species, namely BSA (75.6% sequence identity to HSA; [5]), demonstrating specificity (Fig. 3A).

Previous studies from our laboratory determined that the cellular uptake of 14C-Dp44mT occurred via a saturable carrier/receptor-mediated mechanism [34] (Fig. 7B). Evidence for this mechanism was also obtained in the current investigation in the absence of HSA, with 14C-Dp44mT uptake saturating at 5-10 μM (Fig. 3E inset). However, the addition of HSA led to a high-capacity, saturable, uptake process with saturation occurring at a Dp44mT concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 3E). Hence, in the presence of HSA, there was evidence of an important second saturable mechanism of Dp44mT uptake. Moreover, HSA-stimulated Dp44mT uptake was inhibited by an excess of unlabeled HSA (Fig. 3F), suggesting excess HSA competes with the Dp44mT-HSA complex for HSA membrane-binding sites (Fig. 7C).

14C-Dp44mT Uptake is Increased by HSA in a Variety of Cell-Types

14C-Dp44mT uptake was also augmented by HSA in a variety of cancer cell lines and a non-neoplastic, mortal cell-type (Supplementary Fig. 2A). These observations demonstrated that the HSA-mediated increase of 14C-Dp44mT uptake was a commonly observed mechanism that was not unique to one cell-type. However, there was some cell-type specificity, and the process was not present in some neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells. This finding suggested the differential expression of HSA receptors/binding sites between cell-types. The HSA-mediated Dp44mT uptake in a variety of normal and neoplastic cells did not correlate with the expression of a panel of well known HSA receptors [36], suggesting their lack of involvement in the augmented 14C-Dp44mT uptake mediated by HSA.

Mechanism of HSA-Mediated Dp44mT Uptake

Interestingly, 125I-HSA uptake studies indicated the presence of saturable HSA-binding sites on SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 4A), although Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH did not significantly affect 125I-HSA uptake (Fig. 4Bi-iii). Indeed, it was demonstrated that in the presence of HSA, 14C-Dp44mT uptake occurs through a second, high capacity, low affinity, saturable process (Fig. 3E) that is cell-type specific (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and was inhibited in the presence of excess unlabeled HSA (Fig. 3F). This uptake process had the following three features: (i) it was facilitated by a specific HSA-binding site (Fig. 3E, F); (ii) most cellular HSA was bound to the cell membrane, rather than internalized (Fig. 4A, Bi-iii); and (iii) the avidity of Dp44mT for HSA was relatively low (Fig. 2). Together, these three properties suggest Dp44mT is delivered to cells in a HSA-dependent manner that creates a concentration gradient at the cell surface that enhances subsequent uptake via dissociation and passive diffusion (Fig. 7C). Indeed, HSA-mediated 14C-Dp44mT uptake was not inhibited by glucose-deprivation, metabolic inhibitors, an endocytosis inhibitor, or lysosomotropic agents (Fig. 5A), indicating a passive uptake process (Fig. 7C), rather than active endocytosis which occurred for 125I-HSA (Fig. 5D, 7D) and 59Fe-125I-Tf (Fig. 5B, C, 7E).

In clear contrast to HSA-mediated 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 5A), 125I-HSA uptake by cells was reduced by glucose starvation and inhibitors of energy metabolism or endocytosis (Figs. 5D, 7D). Together, these data suggest augmentation of 14C-Dp44mT uptake in the presence of HSA was independent of HSA internalization. Moreover, in contrast to HSA-dependent and independent 14C-Dp44mT uptake (Fig. 5A), and 125I-HSA uptake (Fig. 5D), the uptake of 59Fe-125I-Tf occurred by the well characterized endocytic mechanism that required acidification [52, 69-71]. This was demonstrated by the inhibition of 59Fe-Tf uptake (Fig. 5C), and to a lesser extent 125I-Tf uptake (Fig. 5B), by lysosomotropic agents (Fig. 7E).

In terms of the mechanism of intracellular uptake of other molecules bound to HSA (e.g., fatty acids), it has been reported that after HSA-binding to the cell membrane, fatty acid-bound albumin undergoes a conformational change [5, 11]. This alteration then results in fatty acid release in the proximity of the membrane for cellular uptake [5, 11]. The subsequent reduced affinity of albumin for the cell surface then leads to its release from the membrane [5, 11]. Similar mechanisms of transport have also been proposed for albumin-bound testosterone and tryptophan [5, 12-14]. In an analogous way to Dp44mT, the low affinity of albumin for testosterone results in the transport of this hormone from the plasma for rapid release and delivery to tissues [5, 80]. Hence, the mechanism reported in this study for HSA-mediated Dp44mT uptake, shows similar characteristics to those described for fatty acids and testosterone.

Binding of Dp44mT to HSA had the lowest relative affinity relative to Bp4eT and PIH (Fig. 2A). Hence, the relatively low affinity of Dp44mT for HSA may facilitate the release of Dp44mT for uptake by passive diffusion (Fig. 7C). In contrast, the relatively higher affinity of Bp4eT and PIH may prevent this (Fig. 7A), and thus, this may explain the differential effects of HSA observed on ligand uptake demonstrated herein. Considering this, it is notable that the ability of HSA to inhibit Bp4eT or PIH uptake was irrespective of the cell-type assessed (Supplementary Fig. 2B-C), suggesting the inhibition was independent of the cell-type. In marked contrast, the stimulation of Dp44mT uptake by HSA was dependent on cell-type (Supplementary Fig. 2A), implicating the crucial role of the cell via the expression of HSA-binding sites in terms of the effect observed.

HSA Potentiates Dp44mT Targeting to Tumor Cells Resulting in Increased Anti-Proliferative and Apoptotic Activity

Significantly, HSA increased the anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of Dp44mT (Fig. 6). Hence, the HSA-mediated increase in 14C-Dp44mT uptake and targeting (Fig. 3A, D, E) enhanced the anti-tumor efficacy of this drug. Conversely, the addition of HSA decreased the anti-proliferative activity of Bp4eT and PIH (Fig. 6A) and inhibited the ability of Bp4eT to induce apoptosis (Fig. 6B). This can be attributed to the HSA-induced inhibition of 14C-Bp4eT and 14C-PIH uptake (Fig. 3B-D), resulting in reduced anti-cancer efficacy of these ligands. These observations could be important for designing new therapeutics based on Dp44mT that enhance its biological efficacy. For instance, albumin-containing nanoparticles have been utilized for improving the activity of standard chemotherapeutics [17, 81, 82]. These agents utilize the enhanced permeability and retention effect and cellular uptake pathways of albumin to enhance drug permeation into tumors [17, 81-83].

Albumin nanoparticles containing the established chemotherapeutic, paclitaxel (marketed under the name Abraxane®), have been approved for the treatment of breast cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer [84-86]. In fact, Abraxane® is less toxic and more effective than conventional paclitaxel [84-86]. Similarly, the development of albumin nanoparticles containing thiosemicarbazones, such as Dp44mT, may enhance the delivery, anti-tumor targeting, selectivity and toxicological profile of this agent. Other thiosemicarbazone-loaded nanoparticles (known as “nanochelators”) have been examined [87], although albumin was not utilized in their composition to enhance uptake. Hence, the development of novel albumin-containing nanoparticles represents an exciting therapeutic avenue.

In conclusion, physiological levels of HSA mediate the enhanced cellular uptake and targeting of Dp44mT, resulting in increased anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity. The uptake of Dp44mT in the presence of HSA could provide therapeutic benefits by delivering greater levels of drug to cancer cells, improving its anti-tumor efficacy and tolerability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

HSA (≥99% purity; Cat. #A8763), BSA (≥98% purity; Cat. #A7906), transferrin (Tf; ≥98% purity; Cat. #T4382), warfarin (Cat. #A2250) and ibuprofen (Cat. #I4883) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The non-radiolabeled ligands, Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH, were synthesized and characterized by established methods [23, 37, 38]. The 14C-labeled chelators, 14C-Bp4eT, 14C-Dp44mT and 14C-PIH, were synthesized by the Institute of Isotopes Ltd (Budapest, Hungary) and were purified and prepared as previously described [34, 35].

Fluorescence Quenching Studies

The fluorescence spectra of HSA (2 μM) was measured with increasing concentrations of the chelators, Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH (0-3.67 μM), after a 2 h incubation at 37°C on a LS-55 spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA) with a 1 cm path-length quartz cell using 15 nm/6 nm slit widths and a thermostat bath. The excitation and emission wavelengths for HSA were 295 nm and 310-450 nm, respectively, with scanning at 5 nm increments.

Circular Dichroism

Far-UV CD data were collected using a Jasco 815 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier- thermostated 6-chamber sample holder at 20°C (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) using a 1 mm path-length quartz cell. Stock solutions of the chelators (1 mM) were prepared in ethanol. Samples containing HSA (2 μM) in the presence and absence of the chelators, Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH (10 μM), or the chaotrope, GndCl (Sigma-Aldrich; 6 M), were prepared in PBS and incubated at 37°C for 2 h prior to measurement. Spectra were collected at 20 nm/min over the range of 200–250 nm, with a sensitivity of 100, step size of 1 nm, digital integration time of 1 s and are the average of five scans with buffer baseline correction and background subtraction. The percentage of α-helices and β-sheets was calculated using DichroCalc [88].

Equilibrium Dialysis Studies

Equilibrium dialysis experiments were performed using standard methods [44]. In these studies, HSA (40 mg/mL) was incubated with an excess of warfarin or ibuprofen (5 mM) or an excess of unlabeled Dp44mT, Bp4eT or PIH (0.5 mM) in PBS for 2 h/37°C in PBS to duplicate the experimental conditions utilized for uptake experiments with the 14C-labeled ligands (see below). The 14C-chelators (25 μM) were then added and the samples were further incubated for 2 h/37°C. The solutions were then placed in a dialysis membrane sac with a 12 kDa molecular weight cut-off (Sigma-Aldrich). These samples underwent dialysis in PBS and were allowed to equilibrate for 24 h/4°C on a rotating mixer. Experiments using the 14C-labeled ligands alone demonstrated that after this incubation period, an equilibrium was established with equal amounts of the label inside and outside of the dialysis sac. Then 1 mL aliquots were taken from the dialysate and the dialysis sac and were processed as previously described [34] using an oxidizer (Sample Oxidizer Model 307; Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences) to prevent quenching. The radioactivity in samples was measured using a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta TriLux β Counter (PerkinElmer) with appropriate calibration standards and background controls. The results were expressed as % of chelator released from the dialysis sack into the dialysate.

Computational Docking Studies

The 2-D structures of the HSA-binding ligands were built using the Schrödinger suite (Schrödinger Inc., New York, NY, USA). Geometry minimizations were performed on all ligand conformations, with all possible ionization states at pH 7.0 ± 2.0, using the OPLS_2005 force field in MacroModel v9.8 and the Truncated Newton Conjugate Gradient. Optimizations were converged to a gradient RMSD below 0.05 kJ/mol, or continued to a maximum of 5000 iterations, at which there were negligible changes in RMSD gradients. Glide v5.8 and the extra precision scoring function were used to estimate the affinities of protein–ligand binding [89].

Initially, warfarin, Dp44mT, Bp4eT and PIH, were docked into Sudlow's site I (warfarin site), where the docking grid was defined and generated based upon the ligand-binding domain of the crystal structure of HSA in complex with warfarin (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 2BXD; www.rcsb.org). Similarly, the binding site for Sudlow's site II (ibuprofen site) was obtained from the co-crystal structure of HSA with ibuprofen (PDB code: 2BXG), where ibuprofen defined the centroid of the docking grid. No constraints were fixed in the active site, allowing the ligands to bind in all possible orientations. Protein preparation and refinement protocols were performed on the structure (Protein Preparation Wizard, Schrödinger).

Cell Culture

The following human cell-types were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA), namely DMS-53 lung carcinoma cells, SK-N-MC neuroepithelioma cells, SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells, MRC-5 fibroblast cells, HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma and the papillomavirus 16 transformed kidney proximal tubule HK-2 cells. All of these cell-types, except DMS-53 lung carcinoma cells, were cultured as previously described [35] in minimum essential media (MEM; Life Technologies) at 37°C. The DMS-53 lung carcinoma cell line was cultured in a similar manner as above using Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI 1640; Life Technologies). These media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma-Aldrich) and the following additives from Life Technologies: 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate, 1% (v/v) 100× non-essential amino acids, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine and 0.28 μg/mL fungizone. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were kindly donated by Mr. P. Pisansarakit (Heart Research Institute, Sydney, Australia) and were cultured according to established techniques [35]. All cells were cultured in an atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air.

Cellular Uptake of 14C-Ligands

The cellular uptake of 14C-chelators was performed in accordance with previously established procedures [34, 35]. Briefly, cells in culture dishes were incubated with 25 μM of 14C-chelator in supplement- and FCS-free media in the presence and absence of HSA (5 or 40 mg/mL), BSA (40 mg/mL) or Tf (5 or 40 mg/mL) for 0-120 min at 37°C. The cellular uptake of 14C-Dp44mT (0.1-150 μM) was also examined as a function of concentration in the absence or presence of HSA (40 mg/mL) at 4 or 37°C over a 2 h incubation. In studies examining the effect of proteins on 14C-chelator uptake as a function of protein concentration, cells were incubated in medium containing HSA or BSA (0-250 mg/mL) for 120 min/37°C. Upon completion of uptake experiments, cells were placed on ice and washed four times with ice-cold PBS. The cells were then resuspended the cells in PBS (1 mL) and Ultima Gold™ scintillation fluid was added (2.5 mL; PerkinElmer). Radioactivity was measured using the β-counter, as described above.

Assay Examining Internalized and Membrane-Bound 14C-Ligand Uptake by Cells

In studies examining the internalized and membrane-bound uptake of the 14C-ligands, the general protease, “Pronase” (Sigma-Aldrich; Cat. #P8811) was used, implementing established methods [49, 52]. Briefly, cells were treated with 14C-chelators (25 μM), washed four times on ice with ice-cold PBS and then incubated on ice with Pronase (1 mg/mL) for 30 min/4°C. Subsequently, cells were removed from the plate on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm/1 min/4°C. The supernatant obtained represents the Pronase-sensitive membrane-bound fraction and the pellet was resuspended in PBS and represents the Pronase-insensitive internalized compartment. Radioactivity in each fraction was assessed as described above.

14C-Dp44mT Cellular Efflux

Examination of 14C-Dp44mT release from pre-labeled SK-N-MC cells was performed using standard techniques [34, 35]. Briefly, SK-N-MC cells were incubated in a similar manner to uptake studies and were pre-labeled with 14C-Dp44mT (25 μM) in the presence or absence of HSA (40 mg/mL) for 120 min/37°C. The cells were then placed on ice, the media removed and the cell monolayer washed four times with ice-cold PBS. Phenol red-free media containing HSA (40 mg/mL; 1 mL; 37°C) was then added to each plate and the cells were re-incubated at 37°C for up to 60 min/37°C. At the end of each reincubation period, the cells were placed on ice and the overlying media was placed into scintillation vials to estimate the level of extracellular 14C-chelator. Then PBS (1 mL) was added to the cells, which were subsequently removed from the plates using a plastic spatula. This suspension was placed into β-scintillation vials and represents cellular-associated 14C-chelator. Radioactivity was determined using a β-counter. Results were expressed as % of 14C-chelator released into the medium.

Western Blot Analysis