Abstract

Background

About 17% of all children suffer from a mental disorder in early childhood, defined as the period up to the age of 6 years.

Methods

This review is based on publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed and the Web of Science, as well as on the authors’ clinical and scientific experience.

Results

In children up to age 2, disorders of emotional and motor regulation are common (ca. 7%), as are feeding problems (25%), which persist in 2% of children to meet the diagnostic criteria for a feeding disorder. Reactive attachment disorder, a serious mental illness, has a prevalence of about 1%: it is more common among children in situations of increased risk, e.g., orphanages and foster homes. Preschool children can develop anxiety disorder and depressive disorder, as well as hyperactivity and behavioral disorders (the latter two mainly in boys). Parent training and parent–child psychotherapy have been found to be effective treatments. There is no evidence that psychotropic drugs are effective in early childhood.

Conclusion

The diagnostician should act cautiously when assigning psychopathological significance to symptoms arising in early childhood but should still be able to recognize mental disorders early from the way they are embedded in the child’s interactive relationships with parents or significant others, and then to initiate the appropriate treatment. Psychotherapy in this age group is still in need of validation by efficacy studies and longitudinal studies of adequate quality.

Epidemiological studies reveal a 16–18% prevalence of mental disorders among children aged 1 to 5 years, with somewhat more than half being severely affected (1– 3). There is evidence that many disturbances occurring in the first year of life that are commonly thought to be transient, e.g., infantile colic (“screaming baby”), persist beyond the first year in about one-third of cases (e1) and constitute risk factors for further disturbances in the child’s later development (e2, e3).

It is currently debated whether disorders at such an early age merit examination and treatment by a child psychiatrist (2). In one American study, only 11% of affected children were referred to a specialist (2, e4). It is often unclear whether an early disorder is best interpreted as an expression of problematic interpersonal relationships or, alternatively, as a potential first sign of individual psychopathology. The uncertainty arises because children develop very rapidly, both biologically and mentally, from birth to age 6; during this time, both normal and pathological mental phenomena may be only fleetingly observed. Neuroscientific studies have made it clear that the quality of early relationships is reflected in the architecture of the brain and thus plays a key role in the development of the child’s personality (4, 5). Basic research on both rats and human beings has shown that pre- and post-natal experiences of deprivation lead to abnormal reactivity of the immature individual’s hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis, mediated by changes in the epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (6, 7).

Early disorders.

The quality of early relationships is vitally important for lifelong mental health.

The younger the child is, the more embedded his or her behavior and biopsychosocial equilibrium are in relationships with parents and other carers. The determination whether any putative manifestation of a mental disorder is truly pathological, or just an expression of normality, can only be made in reference to the child’s current stage of development and its characteristic features. The diagnostic nomenclature in German-speaking countries is not uniform: Cierpka (8) mainly takes a developmental point of view and attempts to describe disorders of development in terms of their embedding in interpersonal relationships, without applying psychiatric diagnoses at this early stage. In contrast, von Gontard (9) tries to follow the psychiatric disorders defined in the ICD-10 and DSM-V diagnostic manuals (10, e5, e6) backward in time, assessing the qualitative and quantitative aspects of their occurrence in early childhood. In the DC:0–3R classification (11), groups of clinical disorders and relationship disorders are defined on distinct diagnostic axes. In this article, we proceed from the point of view of early childhood development, describing typical relationship disorders in early childhood and giving examples of clinical syndromes that influence major biopsychological regulatory systems (food intake, motor function, affect). In a final section, we discuss diagnostic and therapeutic aspects.

Our discussion of these disorders and their treatment is based on articles retrieved by a selective literature search in the PubMed and Web of Science databases, with the search terms “reactive attachment disorder,” “feeding disorder,” “depression,” “anxiety disorder,” “ADHD,” “psychotherapy,” “age 0–6,” and on review articles.

Learning objectives

This article is intended to make readers familiar with:

changes over the course of mental development from birth to the age of 6 years

the conditions under which mental illnesses arise in this age group

the main types of disorder

the basic principles of treatment.

History.

The psychiatric evaluation of young children must take account not only of the symptoms, but also of their context, i.e., the patient’s developmental state and interpersonal relationships.

Concepts in developmental psychology

In recent decades, it has become increasingly clear from the empirical evidence that children, after having their earliest mental experiences in utero, develop from birth onward in a relationship with their primary caregivers and play an increasingly active role in the interaction (5, 12). For a classification by age, see also Box 1. Infants gradually develop a conception of themselves; this development of the self as subject starts from an inborn disposition to form social relationships and then proceeds to increasingly well-defined experiences of the self. Stern describes this as a trajectory that begins with an “emerging self” in the first weeks of life, proceeds to a gradually developing conception of a “core self,” involving a feeling of coherence, and then arrives at a “subjective self,” possessing an inherent theory of its own identity as distinct from others (e7). From the second year of life onward, development progresses to a “verbal self,” with acquisition of the capacity for symbolic use of language and for verbal exchange with other people. This, in turn, gives rise (for example) to the ability to frame the experience of the self, in relation to others, in a form that can be verbally recounted, i.e., a narrative organization of self-perception (e7). In parallel with this development of the infant into a self as subject, there develops an intuitive parental competence to form a relationship with the infant, which is just as much a matter of biological predisposition as the infant’s development. Parents usually behave in a sensitive and strongly expressive way toward their child, and this leads to increased attention on the infant’s part (e8). Thus, in the child’s first year, reciprocally regulated exchange processes take place, in which, over and over again, each party produces pleasurable expressions of affect and also attentively perceives the affect of the other. The infant manifests immediate responsive evaluation of the adult’s intention as expressed by communication. Such affective exchange processes, called “intersubjectivity” (13), provide a basis for the child’s ability to interpret its own or other people’s behavior by ascribing mental states to them (mentalization) (14).

Box 1. Age classification.

Infancy: 0 to 3 years

Toddlerhood: 2 to 3 years

Preschool age: 0 to 5 or 6 years

Active participants.

Children develop from birth onward in a relationship with their primary caregivers and play an increasingly active role in the interaction.

As biological maturation progresses, the child is required again and again to overcome established developmental equilibria in order to contend with new developmental tasks. A typical transitional phase (15) (“organizers of development”) (e9) takes place toward the end of the first year of life, when the child’s relationships become more specific and the child begins to take more interest in joint attention and cooperation with his/her primary caregivers (16). This phase is associated with anxiety, e.g., toward strangers and in situations of separation (e10). The child becomes more aware of being separated from the primary caregiver; this opens up new developmental perspectives but also introduces new, crisis-driven negative affects. Thereafter, increasing mobility and autonomy in the second year of life are associated with euphoria on the one hand, with anxiety and attempts to get close to the caregiver again on the other (e11). Linguistic ability and the development of a verbal self also open up major developmental opportunities but can be associated with sad affects, as the child must give up the illusion of being wordlessly understood and increasingly develops feelings of worry and guilt on perceiving his or her own aggressive affect toward the mother (“depressive position”) (e12). Parents, by dealing sensitively with the child’s urgent desires and needs, help the child cope with such developmental crises from infancy onward (17). In the preschool years, the child must deal with a wider social sphere and develops new forms of affect regulation (e13) and social relationships with peers (18).

Regulatory disorders in important developmental systems such as food intake, motor function, and affect usually have multiple determinants. On the child’s side, the immaturity of biopsychosocial functions, a difficult temperament, and organic risk factors (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux, atopy, brain diseases) can play a role (19). On the parents’ side, problematic internal representations of the child (e14) can be a risk. What results is often a disturbance of interactions involving reassurance, feeding, and/or going to sleep. The younger the child, the greater the extent to which the individual manifestations of disease are bound up with disturbances of intersubjectivity and interpersonal relationships. Thus, the diagnosis must include not only the pathology of the individual, but that of the relationship as well.

Types of disorder

Relationship disorders: reactive attachment disorder

Typical types of problematic parental relationship qualities, as described in DC:0–3, are listed in Box 2 (11). For example, the child’s development may suffer because of an overinvolved parental attitude, i.e., excessive domination and too little autonomy for the child, or, alternatively, from an underinvolved attitude, i.e., insensitivity or even neglect.

Between processes and crises.

Early development runs through a series of transitional processes and crises.

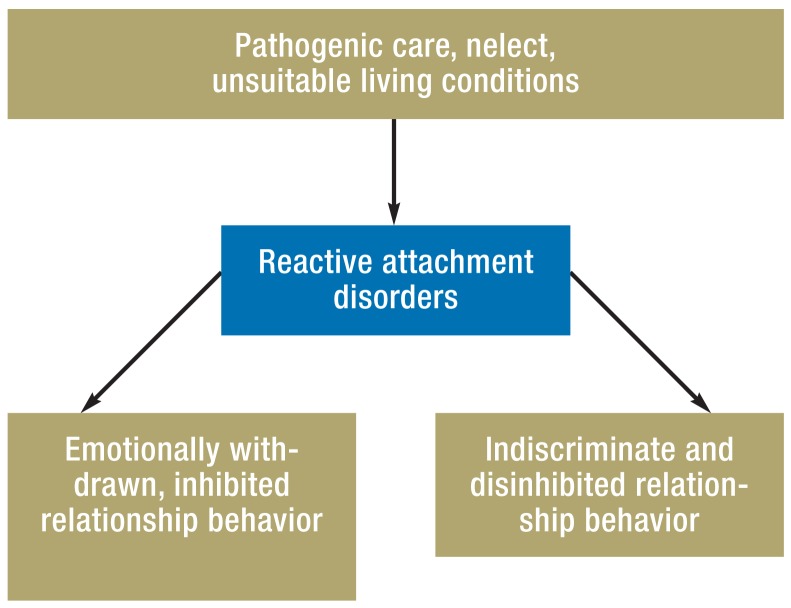

A hostile or abusive parental attitude toward a small child is highly pathogenic. It can lead to marked deficits in the child’s cognitive and emotional development, and in his or her physical development as well (e.g., stunted growth). Reactive attachment disorder (Figure) is the prototypical primary relationship disorder. All psychiatric classification systems agree that the etiologic factors for this disease entity include insufficient parental care, socio-emotional neglect, repeated changes of primary caregivers, and inadequately staffed infant-care facilities (20). Attachment disorder has a prevalence of about 1% in the general population (1) but is much more common in settings where the child is especially at risk, e.g., foster homes and orphanages (e15).

Figure.

Etiology and types of reactive attachment disorde

Joint development.

As the infant develops, so, too, does the intuitive competence of the parents, which is just as much a matter of biological predisposition as the infant’s development.

The key features for the diagnosis of an attachment disorder are persistent neglect as the characteristic etiology, combined with the typical behavior patterns of inhibition or disinhibition. This diagnosis should not be confused with attachment classifications (e17) that are based on the attachment theory of Bowlby (e16), which describe typical mother–child relationship patterns at the end of the child’s first year in relation to brief episodes of separation and reunification (secure, insecure avoidant, and insecure ambivalent/resistant pattern). These are not pathological; rather, they are normal variants of interactive behavior. No reliable data are available on the frequency of comorbid disorders. Hypervigilance and irritability in an infant, toddler, or preschool child should arouse the suspicion of a comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder (e18). In a preschool child, a post-traumatic stress disorder can also express itself in repetitive play with recurrent catastrophic themes (e18).

It is important to distinguish attachment disorders from other disorders, such as autism or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), even if empirically validated differential-diagnostic criteria are not always available. Nonetheless, clinical experience suggests that such distinctions often more closely reflect an idealized view of symptom clusters than they reflect reality: in fact, many complex disturbances can have multiple causes, and the patient’s behavior is often hard to classify unambiguously as either psychosocial-reactive on the one hand, or of primary biological origin on the other.

The origin of attachment disorders.

Reactive attachment disorders arise because of inadequate interpersonal relationships and are characterized by typical behavior patterns.

Unsurprisingly, in view of its etiology, reactive attachment disorder takes markedly different forms in different sociocultural contexts. In some countries, the disorder is common because many infants and small children live in qualitatively and quantitatively understaffed children’s homes/orphanages, owing to unfavorable socio-economic conditions (21). In contrast, in highly developed Western industrial countries, attachment disorder is more often due to intrafamilial deprivation arising from risk factors such as mental illness (particularly addiction) in the parents, disintegration of the family, teenage parenthood, poverty, and transgenerational traumatization (20, e12). Studies of deprived Romanian children adopted by healthy families after their orphanages were closed have shown that the two variants of the disorder are equally common, and that inhibited manifestations carry a more favorable prognosis than disinhibited ones (22). The age of the child upon adoption, the duration of the deprivation, and the quality of the new relationship are all prognostically significant.

Disorders of food intake: feeding disorders

Food intake is a basic, yet complex challenge for the infant. The development of oropharyngeal and general motor function, coordination, and especially interactive behavior while the child eats or is being fed are among the individual maturational steps that all infants must take. By the age of twelve months, infants become increasingly independent and start to explore the food that is offered them, functionally, through motor function, and through smell and taste, in a manner that is strongly culturally dependent (23). The development of autonomy is also constantly being recalibrated during meals (24), as are the child’s modes of dealing with new things and of expressing opposition (e19). The prevalence of diagnosed feeding disorders in 18-month-old infants is 2.5% (1). About 25% of parents subjectively report problems feeding their infant in the first six months of life (e20). Difficulties with food intake arise in up to 80% of developmentally delayed children (23). One-quarter of all very low birth weight preterm infants (weighing less than 1500 g at birth) have feeding problems in the first year of life, with persistence into the fourth year in 25% of cases (25).

Feeding disorders.

Difficulties with food intake can develop into feeding disorders because of biological immaturity of the swallowing process and/or a disturbance of the parent–child interaction.

Feeding disorders come in diverse types and have diverse causes (Box 3), including abnormal parent–child interactions and a wide variety of underlying somatic illnesses. The principal types to be mentioned here are functional dysphagia—often associated with brain injury, cerebral palsy, tracheostomy, preterm birth, and craniofacial malformations (e21)—and feeding disorders of preterm infants after hospital discharge, due to their still immature oral motor coordination (e5, e22). Developmental delay can be associated with difficulty accepting foods of a particular taste or consistency, lack of appetite, or a lack of interest in eating (e23). Children with early childhood anorexia do not show any feeling of hunger or interest in eating and use meals only to explore and interact, with marked failure to thrive as the result.

Box 3. Types of feeding disorder*.

-

Feeding disorder of state regulation

Stagnation or loss of weight is characteristic; the child has difficulty achieving and maintaining a calm, contented state while eating (too sleepy, agitated, or too distressed).

-

Feeding disorder of caregiver–infant reciprocity

Lack of age-appropriate reciprocity during feeding (no eye contact, smiling, or vocalization). Often, complex disturbance of mother–child relationship and failure to thrive.

-

Infantile anorexia

Refusal of food and failure to thrive. Hardly any sign of hunger or interest in food; mealtimes are used for exploration and interaction with caregivers, rather than for eating.

-

Sensory food aversions

Consistent avoidance of specific foods with a particular taste, structure, or smell (often on the introduction of semisolid food). Preferred foods are eaten without any problem. Possible consequences: nutrtitional deficits, impaired oral motor function.

-

Feeding disorder associated with a concurrent medical condition

Difficulty getting through meals, e.g., in heart or lung disease; danger of stagnation or loss of weight.

-

Feeding disorder associated with gastrointestinal insults

Food refusal after single or repeated aversive or distress-inducing stimulation of the upper gastrointestinal tract, e.g., gagging, vomiting, reflux, canulation, suction. Feeding induces post-traumatic stress.

*(modofied from [11])

The consequences of overestimation.

Overdiagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in toddlers and preschool children is often due to inappropriately high expectations of their ability to regulate motor function and attention.

With so many different etiologies, the diagnostic evaluation of early childhood feeding disorders clearly must be interdisciplinary. Important elements of the evaluation include a thorough history (key points: gestation, delivery, early childhood development, eating behavior, and any mental disorders of the parents, especially eating disorders), height and weight percentiles, standardized developmental assessment (e.g., on the Bayley or Griffith scale), and, if necessary, examination by a pediatric neurologist and pH measurement to rule out gastroesophageal reflux disorder. Dysphagia affecting any phase of the swallowing process can be classified in standardized fashion on the penetration-aspiration scale (e24); dysphagia can be associated with disturbed eating behavior and can lead to a feeding disorder. Video recordings of the home feeding and play situations can be a good start for the diagnostic evaluation of parent–child interactions.

Persistent feeding and eating difficulties can develop into broader disturbances of the parent–child interaction, especially when overchallenged parents react with intrusive behavior. Eating problems often persist: 48% of children with eating disturbances at 6 months still ate irregularly at 2–4 years of age (e25). Infants whose mothers have an eating disorder are at higher risk of a feeding disorder (e26), but there are no prospective studies on the putative association of feeding disorders in early childhood with eating disorders in adolescence and adulthood.

Multiple regulation disorders.

Disorders affecting multiple regulatory systems in early childhood are associated with the development of externalizing disorders when the child reaches school age.

Disorders of motor regulation/hyperactivity

In so-called disorders of regulation, the child has difficulty regulating his or her emotional, behavioral, and motor responses to sensory stimuli; this leads, in turn, to impaired development and impaired functioning (e.g., disturbed parent–child interactions because of excessive crying). These disorders are classified into hypersensitive types (fearful-cautious and negative-defiant types), hyposensitive types (abnormally low responsiveness), and stimulation-seeking, impulsive types (11).

Behavor and affect dysregulation.

Infants react to caregivers’ anxiety and depressive affects with marked behavioral and affective dysregulation.

It is unclear up to what age one should still speak of a hypersensitive motor regulation disorder that manifests itself primarily in the parent–child relationship, and from what age onward one should consider the problem to be the onset of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (26). 1738 mothers of children aged 3–6 years who were attending preschool in Germany, when asked by questionnaire, characterized 10.8% of their children as noticeably hyperactive or inattentive (27), but the rate of reported hyperactivity declined markedly one year after the children (especially girls) began the first grade. These figures suggest that parents and teachers often overestimate preschool children’s normal capacity for motor regulation and are therefore also too quick to consider a child hyperactive. The true prevalence of ADHD in the preschool years, as diagnosed by standardized interviews in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS), is 1.5% (e27). Hyperactive manifestations in the preschool years are “hard to distinguish from normal behavior, which is highly variable” (e5). A number of structured clinical interviews are now available for the diagnostic evaluation of preschool children, including the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment ([e28]; see also [e29]) and preschool-age questionnaires (e.g., the Connors Early Childhood Scales [e31] and, in German, Fremdbeurteilung für ADHS im Vorschulalter [e30]).

Post-partum depression.

Close monitoring of cognitive and emotional development is indicated for children whose mothers suffered from post-partum depression after they were born.

Simple disorders of regulation in infancy generally have a good prognosis (e32), but disorders affecting multiple regulatory systems are associated with the later development of externalizing and hyperkinetic disorders (28, 29). Preschool ADH manifestations persist into the school years in about 60–80% of cases (e33). The severity of manifestations, comorbidities, and the degree of impairment of executive function (e34), along with psychosocial risk factors (e2), are important predictors for persistent manifestations. Multiple efficacy studies have shown that parent training sessions aimed at improving pedagogical coping strategies with the child’s problem are effective and improve the long-term outcome (e35– e39). American trials of the treatment of preschool children with methylphenidate have shown that this is effective, but fraught with a high rate of side effects (e40, e41)

Affect disorders: anxiety and depression

Even in the first few months of life, children display various emotions, such as interest, satisfaction, or distress. By the end of the first year, the repertoire of emotional reactions is more finely grained, encompassing joy, satisfaction, annoyance, disgust, surprise, interest, and sadness (e42). At about the age of eight months, the infant begins to show anxiety more frequently. The regulation of affect, particularly in the first few months of life, is closely linked with the affects of the primary caregiver (usually the mother). Infants react to caregivers’ anxiety and depressive affects with marked behavioral and affective dysregulation (crying, protest, affective withdrawal) (30).

Children of mothers with post-partum depression often have cognitive and emotional deficits at an early age (e43). They often show a depressive affect in interactions with their mothers, and with other persons as well, which implies internalization of the depressive affect (31). Disturbed early relationships and a genetic predisposition to depression (e44) are causative factors for depression in later life. In a longitudinal study, Murray et al. showed that children of mothers with post-partum depression are more than three times as likely to suffer from depression themselves, with a 41.5% prevalence by age 16 (32).

Skovgaard et al. (2007) found some type of affective disorder (depressive mood, anxiety, or rage lasting at least two weeks) in 2.8% of a representative sample of 18-month-old Danish children (1). In an American epidemiological study, 10.5% of a sample of preschool children were found to be suffering from emotional disorders (anxiety and depression), and 2.1% met the diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder (2). Klein et al. (2014) studied 1034 German preschool children whose manifestations were rated by their mothers: 5.8% were found to have signs of internalization beyond the pathological threshold, which remained moderately stable into school age. The prevalence of diagnosable depressive disorders rises with age; unlike the externalization disorders, these are roughly equally common in boys and girls (33).

Irritability and inhibition while at play.

Irritability and inhibited behavior during play are typical signs of depression in preschool children.

Depression in preschool children is characterized by an irritable affect lasting more than two weeks. At this early age, affect disorders are only rarely persistent and uninterrupted, as they often are in adolescence and adulthood (Box 4). Special attention must be paid to play behavior: lack of desire to play, decision-making difficulties, and self-abasement can be early signs of depression (34). Subclinical depressive signs can also be significant even though they do not reach the threshold of a diagnosable depressive disorder, e.g., frequent tearfulness or irritability. Anxiety disorders in preschool children (prevalence, 7.7% [2]) are harder to distinguish from normal developmental anxiety; common varieties are separation anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobic disorders. The combination of anxiety that impairs the child in everyday life together with clinically diagnosable or subclinical depression has been found to be a particularly worrisome constellation in preschool children (35).

Box 4. Symptoms of depression in preschool children*.

Depressive or irritable mood

Lack of interest in, and pleasure from, play

Feelings of worthlessness and guilt associated with themes of play

Suicidal or self-destructive themes in play

Present for at least two weeks (not necessarily persistent and uninterrupted)

*(modified from [10)

Somatic developmental deficits.

Somatic developmental deficits and negligent child-care conditions must not be overlooked in the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of small children with mental disorders.

Diagnosis and treatment

As most of these disorders are highly complex, their diagnostic evaluation should be carried out by specialists (physicians, psychologists, etc.) and interdisciplinary teams that are experienced with patients in this age group (e45) (Boxes 5, 6). The evaluation should include an assessment of potential disorders along three axes—biological, social, and psychological. Once the evaluation has been concluded, a definite treatment plan should be developed, with the goal not only of treating the current problem but also of preventing its recurrence at a later age.

Box 5. Standards for psychiatric evaluation*.

Family interview

Observation of mother–father–child interactions

Assessment of cognitive, social, and emotional developmental functions

Assessment of parental sensitivity, affective responsiveness, and ability for self-regulation

Use of standardized observation instruments

Interdisciplinary findings

Diagnostic formulation including symptom diagnosis, relationship diagnosis, degree of severity, and prognosis

Multiple follow-up evaluations in the long term

*(modified from [e45])

Box 6. Methods of parent–child psychotherapy.

-

Interactional guidance (McDonough)

Parent–child interactions are recorded on video, and the parents are then instructed, with the aid of video feedback, on how to improve their interactive competence.

-

Child-centered psychotherapy (“watch, wait, and wonder”) (Cohen)

Mothers are helped, in non-directive fashion, to open themselves to the opportunities for forming a relationship with their children, and to establish an interaction with them.

-

Psychoanalytic-psychodynamic child–parent psychotherapy (multiple proponents, including Cramer, Cierpka, Salomonsson)

During the therapeutic sessions, parent–child interactions are observed, the observations are verbally described, and unconscious conflicts in the parents’internal world are discussed and interpreted.

Treatment planning.

Once the evaluation has been concluded, a definite treatment plan should be developed, with the goal not only of treating the current problem, but also of preventing its recurrence.

Extended treatment.

Motor abnormalities, linguistic deficits, and other specific developmental impairments must be recognized and treated appropriately, e.g., with speech therapy, physiotherapy, or ergotherapy.

Harmful substances.

Disorders of regulation may be caused or exacerbated by biological factors, such as intrauterine exposure to nicotine or other harmful substances.

Parent–child psychotherapy.

Parent training and parent–child psychotherapy are effective methods of treatment for early interaction disorders and mental disorders in early childhood.

Somatic factors, even if only mild, are highly relevant to the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in early childhood. Motor abnormalities, linguistic deficits, and other specific developmental impairments must be recognized and treated appropriately, e.g., with speech therapy, physiotherapy, or ergotherapy. Disorders of regulation, in particular, may be caused or exacerbated by biological factors such as intrauterine exposure to nicotine or other harmful substances, metabolic disorders, congenital malformations, etc. (Box 7). Severely impaired physical development (e.g., a child who is underweight because of a feeding disorder) necessitates hospitalization in a parent–child setting. There is no evidence for the efficacy of psychotropic drugs in very young children (e46), nor have their potential side effects and long-term effects on the brain been studied. The social context of the disorder must be taken into account in its diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Signs of neglect, emotional deprivation, or other types of child abuse must not be overlooked. Psychotherapeutic interventions can help only if the child’s psychosocial life situation provides an adequate basis for normal mental development. In some cases, the child’s problem is best dealt with in collaboration with the local child welfare and child protection authorities.

Box 7. Warning signs that call for psychiatric evaluation and (potentially) intervention.

-

Reactive attachment disorders

Watchful waiting on the physician’s part may be justified when a child with an attachment disorder is in a non-depriving living situation (e.g., a foster family) and mainy shows signs of inhibition.

Children who are persistently exposed to harmful influences (neglect, traumatizing environment), or who show signs of disinhibition or repeatedly negative contents of play, need timely intervention with consultation of a specialist in child psychiatry.

-

Feeding disorders

The physician is justified in playing a supportive and advisory role if the feeding problem has not led to stagnation of weight or linear growth, if the child’s cognitive and emotional development is proceeding normally, and if parent–child interactions are positive in other areas of everyday life.

In case of stagnation or slowing of the normal gains in height and weight, or a generalized interaction disturbance resulting in intense familial stress, a specialist in child psychiatry should be consulted for an interdisciplinary diagnostic evaluation and consideration of the treatment options.

-

Motor dysregulation/ADHD

Mild symptoms call for supportive parent counseling and reduction of psychosocial stress factors.

Accompanying symptoms of anxiety and depression, or marked and persistent hyperkinetic behavior, shold be evaluated and treated by a specialist. Psychotropic drugs should be given only when recommended for strict indications by a board-certified child psychiatrist.

-

Affect disorders

Watchful waiting and counseling of the parents are indicated if the child manifests transient mood disturbances or specific anxieties (such as separation anxiety) that do not severely hinder development—for example, making contact with other children or going to kindergarten.

Children who have a marked deficiency of pleasure during play and a persistently negative mood for two weeks or more, accompanied by symptoms of anxiety and depression, should undergo specialized evaluation and, if indicated, therapeutic intervention.

The German-Speaking Association for Infant Mental Health (GAIMH) has proposed standards for the treatment of infants and toddlers in collaboration with their parents and other caregivers (www.gaimh.org). While patient guidance and counseling mainly involve the utilization of available resources and short-term, developmentally appropriate support as a preventive measure, psychotherapy is a scientifically informed method of treating children in collaboration with their parents and/or other caregivers, with the goal of curing, or at least alleviating, mental illness.

The current state of the evidence on psychotherapeutic interventions is presented in the Table. There have been only a few trials of specific methods of parent–child psychotherapy for children up to their third birthday. The methods studied are diverse, including behavioral (e47), psychoanalytic (36, e48, e49), and non-directive techniques (e50, e51). A Cochrane analysis (37) of eight different trials of group parent-training programs revealed an overall improvement of emotional and behavioral adjustment among the children in the intervention groups (e52). Disorder-specific treatment is available for children aged 3–6 (Table), although only a few studies provide evidence of efficacy specifically for this age group. The children themselves can be therapeutically addressed according to their verbal abilities, e.g., in patent–child interaction therapy with elements of behavioral and play therapy in externalizing (e53) or internalizing (38) disorders, or in short-term psychoanalysis for children with anxiety or depressive disorders (39).

Table. Psychotherapeutic interventions in children up to age 6.

| Indication | Intervention | Age range | Study design | Effect | Authors/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) 0–3 years | |||||

| Problems relating to sleep, feeding, and behavior | Psychodynamic mother–child therapy (PMCT)/ interactional guidance (IG); 6 sessions | <30 months; average, 15 months | RCT: comparison of two treatments, no untreated control group (n = 75) | Improvement in sleep, feeding, and crying problems; improvement in maternal sensitivity (IG) and self-esteem(PMCT); effect strength not reported | Robert-Tissot et al. 1996 [e46] |

| Functional problems in the regulation of feeding and sleep behavior | “Watch, Wait, and Wonder” (WWW)/psychodynamic mother childt herapy(PMCT); ca. 10 sessions | 10–30 months | RCT (n = 67) | Lessened severity of problems (assessed by mother), more secure bonding (WWW) | Cohen et al.1999 [e49] |

| Post-partum depression (mother) | Non-directive (NDT), cognitive behavioral (CBT), psychodynamic therapy (PMCT); ca. 10 sessions | 25 months | RCT: 3 treatment groups and 1 untreted control group (n = 193) | Improvement of depression (PMCT) (transient, −2.6 EPDS points); alleviation of relationship problems with child | Cooper et al. 2003 [e54]Muir et al. 1999 [e55] |

| Post-partum depression (mother) | Mother–child therapyGroup interpersonal therapy; ca. 12 sessions | 6–12 months | RCT (n = 39) | Improvement in depressive symptoms and parental stress; improved maternal attitude to child | Clark et al. 2003 [e56] |

| Impaired mother–child relationship | Psychoanalytic mother–child therapy;average, 29 sessions | <18 months | RCT (n = 80): one treated group, one TAU group | Improved maternal depression (d = 0.39), maternal sensitivity (d = 0.42), and mother–child interaction (d = 0.58) | Salomonsson et al. 2011 [36] |

| B) 4 – 6 years | |||||

| Anxiety disorders | Cognitive behavioral therapy | 4–7 years | RCT: 1 treatment group, 1 untreated group (n = 64) | Significant improvement in symptoms of anxiety in the treated group | Hirshfeld-Becker et al. 2010 [40] |

| Anxiety disorders | Intervention based on parent group | 3–5 years | RCT: 1 treatment group, 1 untreated group (n = 146) | Significant improvement in symptoms of anxiety (effect strength not reported) | Rapee et al. 2010 [e57] |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | Trauma-oriented cognitive behavioral therapy | 3–6 years | RCT: 1 treatment group, 1 untreated group (n = 64) | Significant improvement of PTSD symptoms (mean, from 7.6 to 2.9 symptoms per child) | Scheeringa et al. 2011 [e58] |

| Depression | Parent–child interaction therapy | 3–7 years | RCT: 1 treatment group, 1 control group with psychoeducation (n = 54); 25 dropouts | Significant improvement in depression in both groups (effect of treatment on emotional perception and executive function, d= 0.11/0.83) | Luby et al. 2012 [38] |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TAU, treatment as usual

Prerequisites.

Psychotherapy can help only if the child’s psychosocial life situation provides an adequate basis for normal mental development.

Box 2. Problematic qualities of parental relationships*.

-

Overinvolved

Excessively dominant attitude

Inconsistent affect

Lack of limit setting

-

Underinvolved

Insensitivity to child’s needs

Affectively withdrawn

Neglectful

-

Angry/hostile

Attitude of rejection

Negative affect

Defensiveness

-

Anxious/tense

Excessive worry

Anxious affect

Misunderstanding of child’s behavior

-

Abusive

Proneness to attack the child

Reactivation of memories of own trauma

*(modified from [11])

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate. This CME unit can be accessed until 16 August 2015, and earlier CME units until the dates indicated:

“The Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Barrett’s Carcinoma” (Issue 13/2015) until 21 June 2015,

“De Novo Acute Heart Failure and Acutely Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure” (Issue 17/2015) until 19 July 2015

xzcscsxc. Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following is a risk factor for the development of a reactive attachment disorder?

More than 5 siblings

A multigenerational household

Same-sex parents

Inadequate parental care

A single parent

Question 2

What is the prevalence of attachment disorder in the general population?

12%

8%

5%

1%

0.1%

Question 3

Which of the following is a typical manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder in a small child?

Rigor

Hypervigilance

Repetitive doctor games

Pica

Onychophagia

Question 4

What percentage of parents subjectively experience protracted problems with the feeding of a child under the age of 6 months?

80%

60%

25%

10%

5%

Question 5

Which of the following is a common symptom of depression in preschool children?

Vivid dreams

Loss of interest in, and pleasure from, play

Onychophagia

Secondary enuresis

Self-injurious behavior, e.g., head-banging

Question 6

Which of the following is a standard component of the psychiatric evaluation of toddlers and preschool children?

MRI

Observation of parent–child interactions

Stress tests

A marshmallow test

Video evaluation of sibling interactions or play with friends

Question 7

What percentage of prematurely born children with a birth weight under 1500 g have a feeding disorder in their first year?

2%

5%

10%

25%

50%

Question 8

Which of the following parental qualities is unproblematic?

Overinvolved

Underinvolved

Angry/hostile

Abusive

Expressive/sensitive

Question 9

What feeding disorder of early childhood is characterized by a lack of interest in food, deficient signs of hunger ranging to total refusal of food, and the use of mealtimes for exploration and interaction, rather than for eating?

Feeding disorder of state regulation

Feeding disorder of caregiver–infant reciprocity

Infantile anorexia

Sensory food aversions

Feeding disorder associated with a concurrent medical condition

Question 10

Which of the following is a risk factor for intrafamilial deprivation in industrial countries?

Late parenthood

Above-average family income

Transgenerational traumatization

Triadic family constellation

Patchwork family.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

References

- 1.Skovgaard AM, Houmann T, Christiansen E, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in children 1,5 years of age? The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. 2007;48:62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichstrøm L, Berg-Nielsen TS, Angold A, Egger HL, Solheim E, Sveen TH. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:695–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. The timing and quality of early experiences combine to shape bain architecture. Working paper 5. www.developingchild.harvard.edu. (last accessed on 19 January 2015)

- 5.Roth G, Strüber N. Pränatale Entwicklung und neurobiologische Grundlagen der psychischen Entwicklunf. Frühe Kindheit 0-3. In: Cierpka M, editor. Beratung und Psychotherapie für Eltern mit Säuglingen und Kleinkindern. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2014;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cierpka M, editor. Beratung und Psychotherapie für Eltern mit Säuglingen und Kleinkindern. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. Frühe Kindheit 0-3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gontard Av. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2010. Säuglings- und Kleinkindpsychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria Infancy and Preschool. Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: the process and empirical support. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1504–1512. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000091504.46853.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zero toThree. Revised edition. Washington D. C.: Zero to Three Press; 2005. DC:0-3R: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emde R, Spicer P. Experience in the midst of variation: New horizons for development and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:313–331. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trevarthen C, Aitken KJ. Infant Intersubjectivity: Research, theory, and clinical applications. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. 2001;42:3–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist E, Target M. Stuttgart: Klett- Cotta; 2004. Affetregulierung, Mentalisierung und die Entwicklung des Selbst. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Largo RBC; Thun-Hohenstein. Übergänge: Wendepunkte und Zäsuren in der kindlichen Entwicklung. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht; 2005. Entwicklungsaufgaben und Krisen in den ersten Lebensjahren; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Liszkowski U. A new look at infant pointing. Child Dev. 2007;78:705–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klitzing K von, Burgin D. Parental capacities fro triadic relationships during pregnancy: Early predictors of children’s behavioral and representational functioning at preschool age. Inf Mental Hlth J. 2005;26:19–39. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perren S, Wyl A von, Stadelmann S, Burgin D, Klitzing K von. Associations between behavioral/emotional difficulties in kindergarten children and the quality of their peer relationships. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:867–876. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220853.71521.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papoušek M, Schieche M, Wurmser H, Barth R. Frühe Risiken und Hilfen im Entwicklungskontext der Eltern-Kind-Beziehungen. 2nd edition. Bern: Huber; 2010. Regulationsstörungen der frühen Kindheit. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klitzing K von. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. Reaktive Bindungsstörungen. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, et al. The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2007;48:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing foster care and institutional care for children with signs of reactive attachment disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:508–514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolten M, Möhler E, Gontard A von. Regulations-, Fütter- und Schlafstörungen. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2013. Psychische Störungen im Säuglings- und Kleinkindalter. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatoor I. Feeding disorders in infants and toddlers: diagnosis and treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:163–183. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(01)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zehetgruber N, Boedeker R, Kurth R, Faas D, Zimmer K, Heckmann M. Eating problems in very low birthweight children are highest during the first year and independent risk factors include duration of invasive ventilation. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103 doi: 10.1111/apa.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor DF. Preschool attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review of prevalence, diagnosis, neurobiology, and stimulant treatment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200202001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs S, Klein AM, Otto Y, Klitzing K. Prevalence of emotional and behavioral symptoms and their impact on daily life activities in a community sample of 3 to 5-year-old children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolke D, Rizzo P, Woods S. Persistent infant crying and hyperactivity problems in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1054–1060. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker K, Holtmann M, Laucht M, Schmidt MH. Are regulatory problems in infancy precursors of later hyperkinetic symptoms? Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:1463–1469. doi: 10.1080/08035250410015259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keren M, Tyano S. Depression in der frühen Kindheit. Kinderanalyse. 2007;15:305–326. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray L, Arteche A, Fearon P, Halligan S, Goodyer I, Cooper P. Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring Up to 16 years of age. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein AM, Otto Y, Fuchs S, Zenger M, Klitzing K von. Psychometric properties of the parent-rated SDQ in preschoolers. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2013;29:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luby J, Belden A. Depressive-symptom onset during toddlerhood in a sample of depressed preschoolers: Implications for future investigations of major depressive disorder in toddlers. Infant Ment Health J. 2012;33:139–147. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klitzing K von, White LO, Otto Y, Fuchs S, Egger HL, Klein AM. Depressive comorbidity in preschool anxiety disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2014;55:1107–1116. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salomonsson B, Sandell R. A randomized controlled trial of mother-infant psychoanalytic treatment: I. Outcomes on self-report questionnaires and external ratings. Infant Ment Health J. 2011;32:207–231. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barlow J, Smailagic N, Ferriter M, Bennett C, Jones H. Group-based parent-training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in children from birth to three years old: Cochran Review. The Cochran Library. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003680.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luby J, Lenze S, Tillman R. A novel early intervention for preschool depression: findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:313–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Göttken T, White LO, Klein AM, Klitzing K von. Short-term psychoanalytic child therapy for anxious children: A pilot study. Psychotherapy. 2014;51:148–158. doi: 10.1037/a0036026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:498–510. doi: 10.1037/a0019055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Wurmser H, Laubereau B, Hermann M, Papoušek M, Kries R von. Excessive infant crying: often not confined to the first three months of age. Early Human Development. 2001;64:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(01)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Becker K, Holtmann M, Laucht M, Schmidt MH. Are regulatory problems in infancy precursors of later hyperkinetic symptoms? Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:1463–1469. doi: 10.1080/08035250410015259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Angold A, Egger HL. Preschool psychopathology: lessons for the lifespan. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. 2007;48:961–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-retest eliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.American Psychiatric Association. 5th edition. Wahington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- e6.Remschmidt H, Schmidt M. 3rd ed. Bern: Huber; 1994. Multiaxiales Klassifikationsschema für psychische Störungen des Kindes- und Jugendalters nach ICD-10 der WHO. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Stern D. New York: Basic Books; 1985. The interpersonal world of the infant. [Google Scholar]

- e8.Papousek H, Papousek M. Biological basis of social interactions: Implications of research for understanding of behavioural deviance. J Child Psychol Psyc. 1983;24:117–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1983.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Spitz R. The first year of life. International Universities Press. 1965 [Google Scholar]

- e10.Largo RH. München: Piper; 2010. Die frühkindliche Entwicklung aus biologischer Sicht. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Mahler M. New York: International Universities Press; 1968. On human symbiosis and the vicissitudes of individuation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Klein M. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 1962. Das Seelenleben des Kleinkindes und andere Beiträge zur Psychoanalyse. [Google Scholar]

- e13.Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Seguin JR, et al. Physical aggression during early childhood: trajectories and predictors. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2005;14:3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery. A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975;14:387–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2005;44:1206–1219. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177056.41655.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Bowlby J. I: Attachment. Dt.: Bindung. New York: Basic Books; 1969. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- e17.Ainsworth M, Blehard M, Waters E, Wall S. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1978. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. [Google Scholar]

- e18.Scheeringa M, Zeanah C, Drell M, Larrieu J. Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:191–200. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Shipton D, Drewett RF. How do toddler eating problems relate to their eating behavior, food preferences, and growth? Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1069–e1075. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Lindberg L, Bohlin G, Hagekull B. Early feeding problems in a normal population. Int J Eat Disord. 1991;10:395–405. [Google Scholar]

- e21.Prasse JE, Kikano GE. An overview of pediatric dysphagia. Clinical Pediatrics. 2009;48:247–251. doi: 10.1177/0009922808327323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Crapnell TL, Rogers CE, Neil JJ, Inder TE, Woodward LJ, Pineda RG. Factors associated with feeding difficulties in the very preterm infant. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102 doi: 10.1111/apa.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Bryant-Waugh R, Markham L, Kreipe RE, Walsh BT. Feeding and eating disorders in childhood. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:98–111. doi: 10.1002/eat.20795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Robbins J, Coyle J, Rosenbek J, Roecker E, Wood J. Differentiation of normal and abnormal airway protection during swallowing using the penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1999;14:228–232. doi: 10.1007/PL00009610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Lindberg L, Ostberg M, Isacson I, Dannaeus M. Feeding disorders related to nutrition. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:425–429. doi: 10.1080/08035250500440410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Micali N, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Infant feeding and weight in the first year of life in babies of women with eating disorders. J Pediatr. 2009;154:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Schlack R, Hölling H, Kurth B, Huss M. Die Prävalenz der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Egger HL, Angold A. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): A structured parent interview for The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): A structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant and toddler mental assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- e29.Mingebach T, Roller A, Dalir S, Becker K, Pauli-Pott U. Spezifische und gemeinsame neuropsychologische Basisdefizite bei ADHS- und ODD-Symptomen im Vorschulalter. Kindheit und Entwicklung. 2013;22:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- e30.Döpfner M, Lehmkuhl G, Steinhausen H. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2006. Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit- und Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) [Google Scholar]

- e31.Conners C. New York: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 2009. Conners early childhood scales. [Google Scholar]

- e32.Stifter CA, Braungart J. Infant Colic: a transient condition with no apparent effects. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1992;13:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- e33.Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Lee SS, Willcutt E. Instability of the DSM-IV Subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:896–902. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Berlin L, Bohlin G, Rydell A. Relations between inhibition, executive functioning, and ADHD symptoms: a longitudinal study from age 5 to 8(1/2) years. Child Neuropsychol. 2003;9:255–266. doi: 10.1076/chin.9.4.255.23519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Koerting J, Smith E, McCann DC, Thompson M. Early detection and intervention for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:557–563. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Charach A, Carson P, Fox S, Ali MU, Beckett J, Lim CG. Interventions for preschool children at high risk for ADHD: a comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1584–e1604. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Daley D, Jones K, Hutchings J, Thompson M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in pre-school children: current findings, recommended interventions and future directions. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35:754–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Laforett DR, Murray DW, Kollins SH. Psychosocial treatments for preschool-aged children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14:300–310. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Murray DW. Treatment of preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:374–381. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Ghuman JK, Arnold LE, Anthony BJ. Psychopharmacological and other treatments in preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: current evidence and practice. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:413–447. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1284–1293. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000235077.32661.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Izard CE, Huebner RR, Risser D, Dougherty L. The young infant’s ability to produce discrete emotion expressions. Developmental Psychology. 1980;16:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- e43.Field T. Maternal depression effects on infants and early interventions. Prev Med. 1998;27:200–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.Apter-Levy Y, Feldman M, Vakart A, Ebstein RP, Feldman R. Impact of maternal depression across the first 6 years of life on the child’s mental health, social engagement, and empathy: The moderating role of oxytocin. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1161–1168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of infants and toddlers (0-36 Months) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e46.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie PuP (Behandlung von depressiven Störungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/028-043.html. AWMF Leitlinie (S3): 028-043. (last accessed on 1 July 2015) [Google Scholar]

- e47.McDonough S. Interaction guidance: Understanding and treating early infant- caregiver relationship disorders. In: Zeahnah C, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- e48.Robert-Tissot C, Cramer B, Stern D, et al. Outcome evaluation in brief mother-infant psychotherapies: report on 75 cases. Inf Mental Hlth J. 1996;17:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- e49.Baradon T. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 2011. Psychoanalytische Psychotherapie mit Eltern und Säuglingen. [Google Scholar]

- e50.Cohen N, Muir E, Lojkasek M. watch, wait and wonder: Ein kindzentriertes Psychotherapieprogramm zur Behandlung gestörter Mutter-Kind-Beziehungen. Kinderanalyse. 2003;11:58–79. [Google Scholar]

- e51.Cohen N, Muir E, Parker CJ, et al. Watch, wait and wonder: Testing the effectiveness of a new approach to mother-infant psychotherapy. Inf Mental Hlth J. 1999;20:429–451. [Google Scholar]

- e52.Barlow J, Parsons J, Stewart-Brown S. Preventing emotional and behavioural problems: the effectiveness of parenting programmes with children less than 3 years of age. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e53.Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy and triple P-positive parenting program: a review and meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:475–495. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e54.Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression - 1 impact on maternal mood. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e55.Muir E, Lojkasek M, Cohen N. Watch, wait, and wonder. Toronto: Hincks-Dellcrest Denter. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- e56.Clark R, Tluczek A, Wenzel A. Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A preliminary report. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73:441–454. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e57.Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Ingram M, Edwards SL, Sweeney L. Altering the trajectory of anxiety in at-risk young children. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1518–1525. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e58.Scheeringa MS, Weems CF, Cohen JA, Amaya-Jackson L, Guthrie D. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]