Abstract

Background

The Institute of Medicine 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D specified higher intakes for all age groups compared to the 1997 report, but also cautioned against spurious claims about an epidemic of vitamin D deficiency and against advocates of higher intake requirements. Over 40 years, we have noted marked improvement in vitamin D status but we are concerned about hypervitaminosis D.

Objective

We sought to evaluate the 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) trend over 20 years.

Design

We retrieved all results of serum 25OHD from 1993 to 2013 (n=69 012) that was trimmed to one sample per person (n=43 782). We conducted a time series analysis of the monthly averages for 25OHD using a simple sequence chart and a running median smoothing function. We modelled the data using univariate auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) and forecast 25OHD levels up to 2016.

Results

The time series sequence chart and smoother function demonstrated a steady upward trend with seasonality. The yearly average 25OHD increased from 36.1 nmol/l in 1993 to 57.3 nmol/l in 2013. The ARIMA model was a good fit for the 25OHD time series; it forecasted monthly average 25OHD up to the end of 2016 with a positive stationary R 2 of 0.377.

Conclusions

Vitamin D status improved over the past 40 years, but there remains a dual problem: there are groups at risk of vitamin D deficiency who need public health preventative measures; on the other hand, random members of the population are taking unnecessarily high vitamin D intakes for unsubstantiated claims.

Keywords: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, trend, hypovitaminosis D, hypervitaminosis D

Introduction

Vitamin D supply is changeable, being sourced from skin synthesis following solar exposure, which is curtailed seasonally in high-latitude countries, and from oral intake of natural foodstuffs, fortified foodstuffs and supplements (1). Although sunlight exposure is the predominant natural source of vitamin D, the primacy of oral intake over sunlight exposure both in the prevention and correction of vitamin D deficiency has been known for some time (2). This is apposite to the concerns about sunlight exposure and skin cancer. For these reasons, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011 Report specified dietary reference vitamin D intakes for those with minimal or no sunlight exposure (3). Individuals with intentional or inadvertent sunlight exposure have lesser dependence on oral sources. The recommended daily allowances specified by IOM in 2011 are between 30% and threefold higher than the 1997 recommended allowances (4). Noting the trend for unsubstantiated claims regarding vitamin D, IOM cautioned against exceeding recommended intakes (3, 5).

The IOM gave guidance about the interpretation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) result. First and foremost, they concluded that 25OHD is a biomarker of exposure and not a biomarker of effect: 25OHD is not a validated clinical outcome nor is it a surrogate of a clinical outcome. According to the IOM, 25OHD is a measure of risk: a concentration below 30 nmol/l (12 ng/ml) indicates increased risk of vitamin D deficiency; a concentration of 40 nmol/l (16 ng/ml) corresponds to the estimated average requirement satisfying the needs of half the population; a concentration above 50 nmol/l (20 ng/ml) meets the requirements of 97.5% of the population; a concentration above 125 nmol/l (50 ng/ml) indicates risk of harm (5, 6, 7). Although some expert guidelines advocate higher thresholds and higher doses to achieve these thresholds (8), other recent systematic reviews support the IOM specifications with respect to skeletal and non-skeletal health (9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

We started measuring serum 25OHD in 1973 in clinical samples (14). We conducted a number of clinical studies up to the early 1980s, and noted an extremely high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in the elderly that was easily corrected by low-dose daily vitamin D supplementation (14, 15, 16, 17). Milk fortification with vitamin D started in Ireland in the mid-1980s, although it was not mandatory. This fortification ameliorated greatly the decline in 25OHD over the winter months (18). Over the past 20 years, supplements combining elemental calcium (500 mg) and vitamin D (10 μg) have become readily available, initially on a prescription-only basis but subsequently on an over-the-counter basis. Most recently, manufacturers of high-dose vitamin D supplements up to 125 μg are seeking marketing licences.

While it is gratifying to witness a marked improvement in vitamin D status following practices of fortification and supplementation, much attention is still needed in all countries to address at-risk groups. The counterfactual of spurious claims about an epidemic of vitamin D deficiency is causing an increase in the prevalence of hypervitaminosis D as a consequence of unnecessarily high intakes in excess of IOM specifications (19). For this reason, we sought to evaluate the trend in vitamin D status in Ireland over the past 20 years in order to forecast the future trend.

Methods

Samples and 25OHD methodology

Our hospital has kept a computerised record of all 25OHD results since May 1993. The database includes the following additional variables: date of sample, forename, surname, date of birth, hospital record number and gender. We obtained permission from the Ethics Committee at St Vincent's University Hospital to extract the information. We opted to have no exclusion criteria. The sole selection criterion was to ensure that only one sample per person was included in the database: if a person had more than one sample, then an average was taken for that person. The total number of results extracted was 69 012. Subsequent to trimming the database to one sample per person, the total number was 43 782.

Since 1974, we have measured serum 25OHD by four different techniques: Haddad and Chyu competitive protein binding radioassay from 1974 to 1994 (20); Incstar/Diasorin radioimmunoassay (Diasorin, Inc., Stillwater, UK) from 1994 to 2008; Immunodiagnostic Systems (IDS) radioimmunoassay (Immunodiagnostic Systems Limited, Boldon, Tyne & Wear, UK) from 2008 to 2011; and Elecsys Vitamin D Total (Roche Diagnostics GmBH) from 2011 to the present. Passing and Bablok method comparison and Bland–Altman test of method bias were performed on the comparative data. In addition, we performed a comparison between Elecsys Vitamin D Total and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Details of these assays and method comparisons are given in the Supplementary Methods and materials, see section on supplementary data given at the end of this article. Since April 1991, we have participated in vitamin D external quality assessment scheme (DEQAS) (21) a period covering all four techniques and have been awarded proficiency certification throughout these years. In view of the difference in defining the lower level of detectability (LLD) with the assays over time, we decided to censor 25OHD levels at a functional sensitivity of 10 nmol/l (4 ng/ml), which was the highest LLD concentration determined for each of the four 25OHD methods used.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean and s.d. or CI, and number and frequency. Differences in means were tested using independent t-test. The total group was divided into five ordered categories according to 25OHD levels in keeping with IOM specifications: <10 nmol/l (<4 ng/ml); 10–29.9 nmol/l (4–11.9 ng/ml); 30–50 nmol/l (12–20 ng/ml); >50–125 nmol/l (>20–50 ng/ml); >125 nmol/l (>50 ng/ml). The frequencies of 25OHD, according to these categories, were determined for the entire group, and for the first year and final year; regarding the latter two groups, the independence of row and column categories was tested using the χ 2 test.

Monthly averages for 25OHD were calculated from May 1993 to December 2013 (n=248), and yearly averages for 25OHD were calculated from 1993 to 2013 (n=21). In order to represent the moving average over the 20 years, a linear regression was fitted to the data with the dependent variable being time and the independent variable being monthly average 25OHD levels. The change in yearly average 25OHD compared to baseline year 1993 was calculated; a linear regression was fitted with the year being the dependent variable and change in yearly average being the independent variable.

We conducted a time series analysis of the monthly averages of 25OHD using a simple sequence chart. Then the same data was analyzed using a 4253H smoother, which is a running median smoothing function. Since we did not have independent predictors such as oral vitamin D intake or BMI, we used the univariate auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) for time series modelling. ARIMA decides what the amount of lag for the series should be for both series values and errors. The model seeks to explain the following: trend, which is defined as the long term direction of the time series; seasonality, which is defined as repeated behavior that occurs at regular intervals; cycles, which are defined as up or down patterns that are not seasonal; and, natural variation. The performance of the ARIMA model was assessed in four ways: first, the plot of the model against the historic series was inspected; secondly, the errors of the model were examined on a sequence chart to determine whether errors have a constant variance (homoscedastic) or a changing variance (heteroscedastic); thirdly, the distribution of the error terms both with and without outliers was tested for normality by Kolmogorov–Shapiro; fourthly, the model was rebuilt excluding the final 3 years, followed by comparison of the forecasted values with the actual values. Finally, we used the ARIMA model to forecast 25OHD levels up to 2016. The stationary R 2 was chosen as the model fit statistic, because it compares the stationary part of the model to the simple mean model, which is preferable to the usual R 2 when there is a trend or seasonal pattern. The stationary R 2 can be negative and has a range of negative infinity to +1; a negative value indicates that the forecasted model is worse than the baseline model, and a positive value means that the forecasted model is better than the baseline model. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 21.0 (Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The mean±s.d. for 25OHD was 54.6±31.4 nmol/l (22.1±12.8 ng/ml) with the range being <10 to 971 nmol/l (<4 to 395 ng/ml). The mean±s.d. for age was 49.8±25.6 (range: birth to 105) years; 66.7% were women and 32.3% were men. Women had higher 25OHD compared to men (56.2±31.2 vs 51.4±31.4 nmol/l, 22.8±12.7 vs 20.2±12.8 ng/ml, t=15.0, P<0.001). The yearly number of samples increased steadily from 741 in the first full year (May 1993 to April 1994) up to 7887 in 2013. Over the 20 years, sampling was evenly distributed throughout the 12 months of the year. The yearly mean±s.d. 25OHD increased from 36.1±24 nmol/l (14.4±9.6 ng/ml) in the first year to 57.3±37.7 nmol/l (23.0±15.1 ng/ml) in 2013.

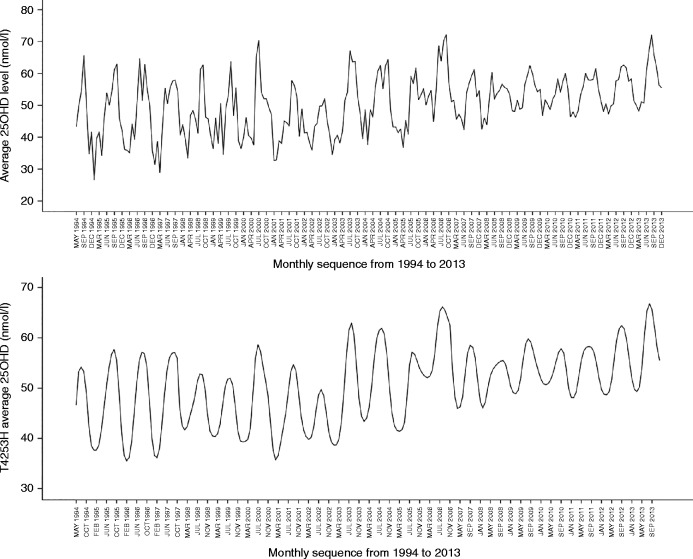

Prevalence of 25OHD categories

The frequencies, over the 20 years from 1993 to 2013, according to ordered 25OHD cut-points were as follows: 2.1% <10 nmol/l (4.0 ng/ml); 23.1% between 10 and 29.9 nmol/l (4.0–11.96 ng/ml); 26.7% between 30 and 50 nmol/l (12.0–20.0 ng/ml); 47.8% between >50 and 125 nmol/l (20–50 ng/ml); and 2.3% >125 nmol/l (50 ng/ml). In the first full year (May 1993 to April 1994), compared to the final year in 2013, the respective frequencies were as follows: 15.3% vs 2.7%; 32.3% vs 21.6%; 26.9% vs 23.7%; 24.9% vs 48.2%; and 0.7% vs 3.8% (χ 2=414, P<0.001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Histogram showing significant change in prevalence of 25OHD categories according to IOM specifications between the first year (May 1993 to April 1994) and the final year (2013) (χ 2=414, P<0.001).

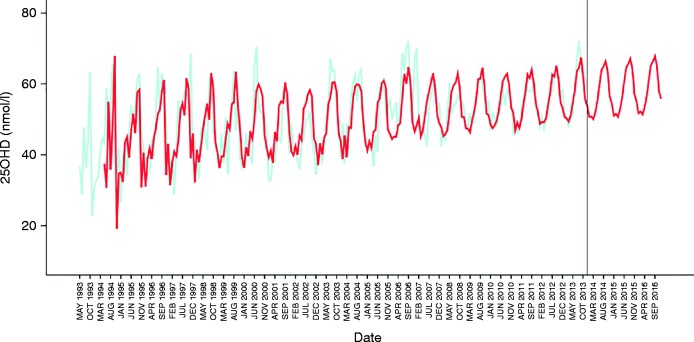

Linear regression analysis

The scattergrams of the monthly average 25OHD and the difference in yearly average 25OHD between 1993 and 2013 displayed an upward trend (Fig. 2). The regression line for monthly-average 25OHD was as follows: 25OHD (nmol/l)=month×0.057+43 (nmol/l), r=0.428, P<0.001. The increase in the average 25OHD level per 1 month was 0.057 nmol/l (0.023 ng/ml), implying an increase of 0.68 nmol/l (0.28 ng/ml) per year over the last 20 years. The regression line for the change in yearly-average 25OHD was as follows: Δ25OHD (nmol/l)=year×0.68 (nmol/l), r=0.825, P<0.001 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Scattergram of monthly average 25OHD since 1993 (n=248) (upper panel) and scattergram of change in yearly average 25OHD compared to baseline of 1993 (n=21) (lower panel).

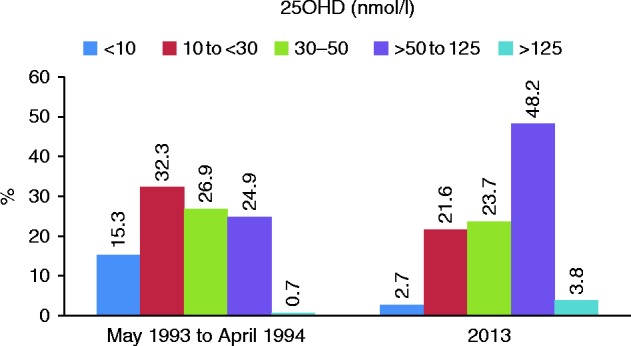

Time series analysis

Visual inspection of the sequence chart of the monthly average 25OHD time series demonstrated an upward trend, seasonality in the series and a reduced variation in the data over time (Fig. 3). The latter observation was consistent with an increase in sample size over time that narrows the CIs. In order to visualize better the pattern of the data, the natural variation was suppressed by smoothing the time series using a 4253H smoother; the seasonality of the data is more apparent as well as the upward trend (Fig. 3). The ARIMA model was superimposed on the original data (Fig. 4). The model does not attempt to fit the first 12 months of the data due to the fact that the model is seasonal and requires this initial information to begin the model. As can be seen in the sequence chart, it takes into account the seasonality of the data. It can be seen that the model fits the data. The residuals were plotted on a sequence chart (figure not shown). The mean value of the residuals was −0.39 (CI: −0.51 to 1.29) nmol/l but the distribution lacked normality (P=0.003). Following removal of the outliers, the mean value of the residuals was −0.03 (CI: −0.84 to 0.78) nmol/l and it passed the test of normality (P=0.200). The rebuilt model using data from 1993 to 2010 predicted accurately the monthly values through 2011, 2012, and 2013 (figure not shown).

Figure 3.

Sequence chart of monthly average 25OHD (upper panel) and sequence of same data after smoothing with 4253H smoothing function (lower panel).

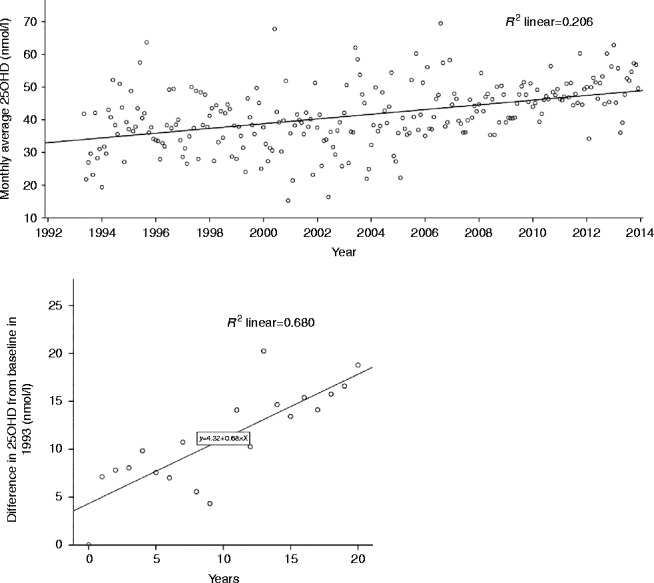

Figure 4.

Forecast of average monthly 25OHD levels for 2014–2016 based on the ARIMA model. Predicted 25OHD is depicted in red that is based on ARIMA modelling of monthly average 25OHD as depicted in light green.

In view of the above performance, the ARIMA model was used to forecast average monthly 25OHD through 2016 as shown in the sequence chart (Fig. 4). As expected, the forecasted values for 2014, 2015, and 2016 have the expected seasonality, trend and similar variance to the prior estimation period. The stationary R 2 was positive at 0.337, indicating that the forecast model was suitable. Table 1 contains the exact forecasts for 25OHD with upper and lower confidence limits for each month from 2014 to 2016.

Table 1.

Predicted monthly average 25OHD with confidence limits over 3 years from 2014 to 2016.

| Month | 25OHD nmol/l | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | LCL | UCL | |

| Jan-14 | 50.7 | 38.0 | 63.5 |

| Feb-14 | 50.8 | 37.8 | 63.9 |

| Mar-14 | 50.1 | 37.0 | 63.1 |

| Apr-14 | 52.1 | 39.0 | 65.2 |

| May-14 | 55.2 | 42.2 | 68.3 |

| Jun-14 | 59.8 | 46.8 | 72.9 |

| Jul-14 | 63.9 | 50.9 | 77.0 |

| Aug-14 | 65.0 | 51.9 | 78.0 |

| Sep-14 | 66.4 | 53.3 | 79.4 |

| Oct-14 | 63.6 | 50.5 | 76.6 |

| Nov-14 | 56.4 | 43.4 | 69.5 |

| Dec-14 | 54.5 | 41.4 | 67.5 |

| Jan-15 | 51.1 | 38.0 | 64.1 |

| Feb-15 | 51.5 | 38.4 | 64.6 |

| Mar-15 | 50.8 | 37.7 | 63.8 |

| Apr-15 | 52.8 | 39.7 | 65.9 |

| May-15 | 55.9 | 42.9 | 69.0 |

| Jun-15 | 60.5 | 47.4 | 73.6 |

| Jul-15 | 64.6 | 51.5 | 77.7 |

| Aug-15 | 65.7 | 52.6 | 78.7 |

| Sep-15 | 67.0 | 54.0 | 80.1 |

| Oct-15 | 64.3 | 51.2 | 77.3 |

| Nov-15 | 57.1 | 44.1 | 70.2 |

| Dec-15 | 55.1 | 42.1 | 68.2 |

| Jan-16 | 51.8 | 38.7 | 64.8 |

| Feb-16 | 52.2 | 39.1 | 65.3 |

| Mar-16 | 51.5 | 38.4 | 64.5 |

| Apr-16 | 53.5 | 40.4 | 66.6 |

| May-16 | 56.6 | 43.5 | 69.7 |

| Jun-16 | 61.2 | 48.1 | 74.3 |

| Jul-16 | 65.3 | 52.2 | 78.4 |

| Aug-16 | 66.3 | 53.3 | 79.4 |

| Sep-16 | 67.7 | 54.7 | 80.8 |

| Oct-16 | 65.0 | 51.9 | 78.0 |

| Nov-16 | 57.8 | 44.7 | 70.9 |

| Dec-16 | 55.8 | 42.7 | 68.9 |

LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit.

Discussion

Vitamin D status has improved immensely in Ireland over the past 40 years following the advent of fortification of foodstuffs and the ready availability of low-dose vitamin D supplements. Our earlier studies were conducted prior to the availability of fortified milk and vitamin D supplements. Milk fortification was initiated in the mid-1980s, and the range of vitamin D supplements have increased steadily starting in the early 1990s. In addition, inflated claims regarding the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency has led to undue public concern and has fuelled the practice of healthy individuals self-medicating with vitamin D supplements (3, 5). Our earlier studies showed that about 80% of infirm elderly had 25OHD levels below 30 nmol/l, but we still have a problem in 2013 with over 24% of the samples having 25OHD below 30 nmol/l (12 ng/ml). We now have a second concern with 3.8% individuals having 25OHD >125 nmol/l (50 ng/ml). A population-based survey in Ireland from 2008, as compared with our laboratory-based survey, reported that 6.7% had 25OHD below 30 nmol/l (12 ng/ml) and 1.3% had 25OHD >125 nmol/l (50 ng/ml) (22).

The simplest approach to quantifying the magnitude of the increase in 25OHD is to compare yearly averages; over 20 years, the yearly average 25OHD level rose by 21.2 nmol/l (8.6 ng/ml) from 36.1 nmol/l to 57.3 nmol/l (14.4 ng/ml to 23.0 ng/ml). The next level of complexity is the linear regression model of yearly and monthly averages; this suggested an average yearly rise of about 0.7 nmol/l (0.28 ng/ml). The regression model is a poor-fitting model for the historic data with respect to making specific monthly predictions; at best, it represents the moving average values over time. Extrapolation of these regression results into the future could lead to non-sensible results when extending far beyond the range of the data. By comparison, the time series analysis is best for forecasting the upward trend in vitamin D status because it takes account of seasonality. Although seasonal variation of 25OHD is very well documented and easily explained as a consequence of seasonal terrestrial ultraviolet radiation, seasonality in time series analysis is a generic term for describing change over any recurring time period such as a day, a week, a month, a quarter of a year or any other longer interval. Our ARIMA model performed well on the 1993–2013 dataset, indicating that the model should be accurate when forecasting future values. The model was extended to the end of 2016. There is no reason to believe that this trend will not be valid over the next 3 years.

Just as we previously highlighted two decades ago the primacy of oral intake over sunlight exposure in the correction and prevention of hypovitaminosis D (2), the only explanation for the inexorable rise in 25OHD levels is the increase in oral intake. Increased travel to regions at lower latitudes, though not recorded, would have been a minor contributory factor. This increase must be consequent on both fortification and supplementation. Fortification is a means to ensure that the vitamin D status of the population shifts upwards. Fortification is advantageous for all populations given the widespread concerns about hypovitaminosis D, regardless of latitude (23).

There has been much debate on vitamin D requirements in health and disease, especially following the publication of the IOM report. The Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) of the Endocrine Society advocated higher vitamin D intakes (8). The IOM Committee countered with a critique of the CPG and disagreed on three principal points: i) that 25OHD levels of 75 nmol/l (30 ng/ml) or higher compared with 50 nmol/l (20 ng/ml) provided increased health benefits; ii) that all persons are deficient if serum 25OHD levels are below 50 nmol/l (20 ng/ml); and iii) that the CPG incorrectly characterized several large at-risk subgroups, who are covered by the IOM specifications (24). A further weakness of the CPG is the method by which the vitamin D dose response was calculated that results in a twofold or higher underestimate of the dose response and thereby an overestimate of intake requirements (25, 26). According to CPG, the vitamin D dose response is linear and is defined heuristically: 25OHD is expected to increase by 2.5 nmol/l (1 ng/ml) for each 100 IU/day of vitamin D ingested. IOM noted a curvilinear response between vitamin D intake and 25OHD as follows: 25OHD nmol/l=9.9×ln (total vitamin D intake (IU/day)). The curvilinear response has been confirmed by the Vitamin D Supplementation in Older Subjects Study (27, 28). By adhering to IOM advice on interpretation of 25OHD and on specification about intake requirements, it is possible to avoid the trend towards overreplacement. Infants and children seem to be the group at most risk of hypercalcemia due to overreplacement (29, 30). For the elderly, meanwhile, a prudent approach to vitamin D supplementation is likely to yield benefits for bone health, (9, http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph56).

Three other studies have examined trends in 25OHD over time. In the Tromsø Study in the northern part of Norway, 2668 subjects were studied in 1994 and again in 2008. 25OHD increased by a small but significant degree from 53.7±16.3 to 55.3±18.2 nmol/l (21.5±6.5 ng/ml to 22.1±7.3 ng/ml) (P<0.01) (31). Scandinavian countries in early studies had better baseline vitamin D status compared to countries at lower latitudes as a consequence of higher oral intake of vitamin D (2). The Tromsø Study again noted the importance of supplemental intake on vitamin D status. The yearly average 25OHD in our study was much lower in 1993 compared to Tromsø in 1994, but is slightly higher in 2013 than in Tromsø in 2008. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) with data collected from 1988 through 1994 (n=18 883) was compared with NHANES 2001–2004 (n=13 369). An initial study reported considerable decline in average 25OHD from 75 nmol/l (28.0 ng/ml) during NHANESIII to 60 nmol/l (24.0 ng/ml) during NHANES 2001–2004 (32). This apparent decline was explained subsequently by assay drift; it was estimated that there was only a small decline of 1.0–1.6 nmol/l (0.4–0.64 ng/ml) between the two surveys (33, 34). Historically, vitamin D status has been better in the US than Ireland given the longstanding practice of milk fortification with vitamin D and location at a lower latitude (2). The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study, which is an ongoing prospective cohort study of 9423 community-dwelling subjects, measured 25OHD in varying numbers of women and men at three time points: 1995–1997; 2000–2002; and 2005–2007. Over the three surveys, they noted an increase in women from 59.5±20.7 nmol/l (23.8±8.3 ng/ml) to 64.4±23.2 nmol/l (25.8±9.4 ng/ml) to 70.7±24.7 nmol/l (28.3±9.9 ng/ml) and in men from 64.7±23.2 nmol/l (25.8±9.3 ng/ml) to 67.0±23.7 nmol/l (26.8±9.5 ng/ml) to 69.9±25.0 nmol/l (28.0±10.0 ng/ml) (35). Vitamin D supplemental intake increased by a greater amount in women than in men, again demonstrating the relative importance of oral vitamin D intake over sunlight exposure on vitamin D status (35).

Our study has a number of limitations: there was no information about health status, about the reason for sampling, about sunshine exposure, about ethnicity, about dietary intake of vitamin D or about vitamin D supplementation. This was not a population-based sample. It is possible that the reason for testing changed over time: in the early years, testing may have been requested in view of the concerns about vitamin D deficiency, and in later years testing may have been requested for casual reasons. This could have contributed to the 25OH trend. The strength of the study lies in the long duration of the study and the high standard of measurement, especially when initial assays were technically difficult to perform and highly variable (14). Over the past four decades, measuring 25OHD has become less arduous because of the availability of several commercial 25OHD assay manufacturers. This has led to several challenges, including technical competency of laboratorians and assay performance. Assay performance parameters are maximised by participation in an accuracy-based and commutable proficiency scheme such as the DEQAS, which uses the recently available standard reference materials by the American National Institute of Standards and Technology in order to objectively assess assay performance against assigned target values (21, 36, 37). The Vitamin D Standardization Program is advocating performance limits for both reference and routine laboratories (38).

Even though we were one of the early participants in DEQAS prior to May 1993, the time span of this study used four assays with differences as outlined in the Supplementary Methods and materials. Using different assays, Barake et al. (39) have reported that change in 25OHD assays can lead to differences in interpretation of vitamin D status. Prior to conducting the trend analysis, we considered the need to quantify the variability between the different methodologies in order to vindicate the increase in 25OHD observed. Positive and negative biases existed between methods as outlined in the comparative data in the Supplementary Methods and materials. Taking into account these biases, the Haddad method, which was used for the year 1 baseline data point, should correlate well with IDS and Roche, which were used in the latter years of the study. We therefore deduce that the increase in 25OHD over the 20 years is accurate. Any attempt at adjusting results between assays over the 20 years would likely have introduced further error.

Our clinical interpretation of vitamin D status, as judged by measurement of 25OHD, from the outset has been a probabilistic one (15, 40, 41, 42). The concept of 25OHD as a biomarker of nutrient supply and not as an outcome, which was the basis for the IOM report, is fundamental to the definition of inadequacy using a probabilistic method (43). This approach of describing the distribution of 25OHD and its subcomponents is being adopted for the comparison of diverse populations (44). The IOM report did not pursue an implementation strategy, but many experts have supported their position and societies such as the National Osteoporosis Society have drafted guidelines that incorporate the IOM positions (45).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a steady rise in vitamin D status since 1993 in Ireland, having already noted a substantive improvement from the early days of measuring 25OHD in the 1970s–1980s. This increasing trend has the potential to keep rising and to cause more harm than benefit. Individuals who are at risk of vitamin D deficiency need public health strategies of fortification and supplementation with vitamin D in order to achieve IOM-specified intakes. Meanwhile, the remainder of the population, who already have adequate vitamin D status, need to be cautioned against having intakes in excess of those advocated by IOM.

Supplementary data

This is linked to the online version of the paper at http://dx.doi.org/10.1530/EC-15-0037.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Bobby Reidy, Presidion, Dublin, for assistance with statistical analysis.

Declaration of interest

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

References

- 1.Bouillon R, Van Schoor NM, Gielen E, Boonen S, Mathieu C, Vanderschueren D, Lips P. Optimal vitamin D status: a critical analysis on the basis of evidence-based medicine. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:E1283–E1304. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna MJ. Differences in vitamin D status between countries in young adults and the elderly. American Journal of Medicine. 1992;93:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Eds AC Ross, CL Taylor, AL Yaktine, HB Del Valle. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 2011. (available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13050/dietary-reference-intakes-for-calcium-and-vitamin-d) [PubMed]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. In Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride, pp 250–287. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 1997. (available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/5776/dietary-reference-intakes-for-calcium-phosphorus-magnesium-vitamin-d-and-fluoride) [PubMed]

- 5.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:53–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aloia JF. The report on dietary reference intake for vitamin D: where do we go from here? Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:2987–2996. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durup D, Jorgensen HL, Christensen J, Schwarz P, Heegaard AM, Lind B. A reverse J-shaped association of all-cause mortality with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in general practice: the CopD study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:2644–2652. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, Murad MH, Weaver CM, Endocrine Society Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:1191–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Lyons RA, Flicker L, Wark J, Jackson RD, Cauley JA, et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:40–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:146–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on skeletal, vascular, or cancer outcomes: a trial sequential meta-analysis. Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2014;2:307–320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JPA. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g2035. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury R, Kunutsor S, Vitezova A, Oliver-Williams C, Chowdhury S, Kiefte-de-Jong JC. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g1903. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray B, Freaney R. Serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D in normal and osteomalacic subjects: a comparison of two assay techniques. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 1979;148:15–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02938042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenna M, Freaney R, Keating D, Muldowney FP. The prevalence and management of vitamin D deficiency in an acute geriatric unit. Irish Medical Journal. 1981;74:336–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna MJ, Freaney R, Meade A, Muldowney FP. Hypovitaminosis D and elevated serum alkaline phosphatase in elderly Irish people. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;41:101–109. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna MJ, Freaney R, Meade A, Muldowney FP. Prevention of hypovitaminosis D in the elderly. Calcified Tissue International. 1985;37:112–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02554828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenna MJ, Freaney R, Byrne P, McBrinn Y, Murray B, Kelly M, Donne B, O'Brien M. Safety and efficacy of increasing wintertime vitamin D and calcium intake by milk fortification. QJM : Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 1995;88:895–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilbane MT, O'Keane M, Morrin M, Flynn M, McKenna MJ. The double-edged sword of vitamin D in Ireland: the need for public health awareness about too much as well as too little. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2014;183:485–487. doi: 10.1007/s11845-014-1147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddad JG, Chyu KJ. Competitive protein-binding radioassay for 25-hydroxycholecalciferol. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1971;33:992–995. doi: 10.1210/jcem-33-6-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter GD. 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a difficult analyte. Clinical Chemistry. 2012;58:486–488. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.180562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cashman KD, Muldowney S, McNulty B, Nugent A, FitzGerald AP, Kiely M, Walton J, Gibney MJ, Flynn A. Vitamin D status of Irish adults: findings from the National Adult Nutrition Survey. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;109:1248–1256. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Schoor NM, Lips P. Worldwide vitamin D status. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011;25:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen CJ, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G, Kovacs CS, et al. IOM committee members respond to Endocrine Society Vitamin D Guideline. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:1146–1152. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna MJ, Murray BF. Vitamin D dose response is underestimated by Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guideline. Endocrine Connections. 2013;2:87–95. doi: 10.1530/EC-13-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting SJ, Bonjour JP, Payen FD, Rousseau B. Moderate amounts of vitamin D3 in supplements are effective in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D from low baseline levels in adults: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2015;7:2311–2323. doi: 10.3390/nu7042311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher JC, Sai A, Templin T, Smith L. Dose response to vitamin D supplementation in postmenopausal women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156:425–437. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-6-201203200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher JC, Peacock M, Yalamanchili V, Smith LM. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in older African American women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:1137–1146. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanstone MB, Oberfield SE, Shader L, Ardeshirpour L, Carpenter TO. Hypercalcemia in children receiving pharmacologic doses of vitamin D. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1060–e1063. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogiatzi MG, Jacobson-Dickman E, DeBoer MD. Vitamin D supplementation and risk of toxicity in pediatrics: a review of current literature. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99:1132–1141. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorde R, Sneve M, Hutchinson M, Emaus N, Figenschau Y, Grimnes G. Tracking of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during 14 years in a population-based study and during 12 months in an intervention study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171:903–908. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Lacher DA, Schleicher RL, Picciano MF, Yetley EA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988–1994 compared with 2000–2004. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;88:1519–1527. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yetley EA, Pfeiffer CM, Schleicher RL, Phinney KW, Lacher DA, Christakos S, Eckfeldt JH, Fleet JC, Howard G, Hoofnagle AN. NHANES monitoring of serum 25-hydroxyvitaminN D: a roundtable summary. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:2030S–2045S. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.121483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger C, Greene-Finestone LS, Langsetmo L, Kreiger N, Joseph L, Kovacs CS, Richards JB, Hidiroglou N, Sarafin K, Davison KS, et al. Temporal trends and determinants of longitudinal change in 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27:1381–1389. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter GD. Accuracy of 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays: confronting the issues. Current Drug Targets. 2011;12:19–28. doi: 10.2174/138945011793591608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binkley N, Sempos CT. Standardizing vitamin d assays: the way forward. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2014;29:1709–1714. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stockl D, Sluss PM, Thienpont LM. Specifications for trueness and precision of a reference measurement system for serum/plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D analysis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2009;408:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barake M, Daher RT, Salti I, Cortas NK, Al-Shaar L, Habib RH, Fuleihan Gel-H. 25-hydroxyvitamin D assay variations and impact on clinical decision making. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:835–843. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freaney R, McBrinn Y, McKenna MJ. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly people: combined effect of renal insufficiency and vitamin D deficiency. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1993;58:187–191. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenna MJ, Freaney R. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: means to defining hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporosis International. 1998;8(Suppl 2):S3–S6. doi: 10.1007/PL00022725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenna MJ & Murray BF. Vitamin D deficiency. In Endocrinology and Diabetes: A Problem-Oriented Approach, pp 293–304. Eds H Gharib & F Bandeira. New York, NY, USA. Springer, 2013. ( 10.1007/978-1-4614-8684-8) [DOI]

- 43.Taylor CL, Carriquiry AL, Bailey RL, Sempos CT, Yetley EA. Appropriateness of the probability approach with a nutrient status biomarker to assess population inadequacy: a study using vitamin D. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;97:72–78. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.046094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durazo-Arvizu RA, Camacho P, Bovet P, Forrester T, Lambert EV, Plange-Rhule J, Hoofnagle AN, Aloia J, Tayo B, Dugas LR, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D in African-origin populations at varying latitudes challenges the construct of a physiologic norm. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;100:908–914. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.066605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Francis RM, Aspray TJ, Bowring CE, Fraser WD, Gittoes NJ, Javaid MK, Macdonald HM, Patel S, Selby PL, Tanna N. National Osteoporosis Society practical clinical guideline on vitamin D and bone health. Maturitas. 2015;80:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a