Mobility of single-file water molecules determined by H-bonds.

Keywords: water permeability; aquaporins; fluorescence correlation spectroscopy; high speed atomic force microscopy; stopped flow; light scattering; unstirred layer; proteoliposomes, protein reconstitution

Abstract

Channel geometry governs the unitary osmotic water channel permeability, pf, according to classical hydrodynamics. Yet, pf varies by several orders of magnitude for membrane channels with a constriction zone that is one water molecule in width and four to eight molecules in length. We show that both the pf of those channels and the diffusion coefficient of the single-file waters within them are determined by the number NH of residues in the channel wall that may form a hydrogen bond with the single-file waters. The logarithmic dependence of water diffusivity on NH is in line with the multiplicity of binding options at higher NH densities. We obtained high-precision pf values by (i) having measured the abundance of the reconstituted aquaporins in the vesicular membrane via fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and via high-speed atomic force microscopy, and (ii) having acquired the vesicular water efflux from scattered light intensities via our new adaptation of the Rayleigh-Gans-Debye equation.

Movement of water through very narrow membrane channels is different from Poiseuillian flow through macroscopic tubes (1). The diffusive nature of single-file transport (2) and the unaltered fluidity of confined water (3) suggest that the unitary osmotic water channel permeability pf may only vary within the narrow limits that are set by the small length deviations of the single-file region. This is in sharp contrast to the experimental observation that pf alterations stretch over three orders of magnitude (4).

Part of the pf scatter is likely to be caused by technical difficulties: reported pf values for correspondent aquaporins can vary by more than an order of magnitude. For example, pf for human aquaporin-1 (AQP1) ranges from 1 × 10−14 to 16 × 10−14 cm3 s−1 (5). The problem of obtaining correct pf values is also underscored by the differences in the in vitro and in silico order in which pf decreases among the members of the protein family. Three experimental groups reported that pf in AQPZ, the orthodox water channel of Escherichia coli, exceeds pf of the glycerol facilitator from E. coli, GlpF (6–8), whereas three other theoretical groups observed the exact opposite (table S1) (9–11).

Single-file water movement may be governed by interactions with the channel wall or limited by water dehydration at the channel entrance. The dehydration energy penalty arises because the single-file waters only have two of the four usual hydrogen bonds available when entering a channel, which does not provide a surrogate for the waters of hydration. In the presence of pore-lining residues that donate or accept hydrogen bonds, water movement should be limited by the time required for breaking H-bonds, reorientation of the molecules, and reforming H-bonds while traversing the channel. If so, the fastest flow should occur when the interaction between single-file waters and the channel wall is restricted to van der Waals interactions, and no hydrogen bonds are formed as is the case in carbon nanotubes (12).

Water mobility in these tubes and in membrane water channels is best compared to bulk water mobility by means of the diffusion constant DW of the single-file water molecules. DW can be calculated according to the Einstein relation (13, 14):

| 1 |

where z, k0, and vw indicate the average distance between two water molecules in the single-file region, the transport rate, and the molecular volume of one water molecule, respectively.

By inserting pf = 5.43 × 10−14 cm3 s−1 (15) of AQP1 and assuming z = 2.8 Å, we found that Dw ≈ 4 × 10−7 cm2 s−1. This result does not agree with previous estimates of Dw ≈ 4 × 10−6 to 8 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (5, 16) in aquaporins. They have been derived using the equation Dw = lc/AC × pf, where AC is the cross-sectional area of the channel (5, 17). Assuming that channel length lc = z × NW, where NW is the number of single-file waters and that lc × AC = NW × vw, we find that Dw was exaggerated by a factor of 2NW. Thus, the uncertainty in the experimental pf was amplified by the ambiguity in extracting Dw from it.

We now set out to obtain molecular insight into what determines Dw. To obtain precise pf values, we had to overcome the uncertainty in the number of channels per unit membrane area. Otherwise, osmotic channel water permeability Pf,c cannot be dissected from lipid water permeability Pf,l. Pf,l and Pf,c add up to osmotic membrane water permeability (18):

| 2 |

where n is the number of aquaporins per vesicle and dV is vesicle diameter. Previously, the uncertainty in n arose chiefly from the poor repeatability and the limited accuracy of channel abundance determination by Coomassie and silver staining of SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (19). Instead, we used both atomic force microscopy (AFM) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) to accurately measure membrane channel abundance. Therefore, the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was anchored to the N terminus of AQP1. AQPZ and GlpF were modified by site-directed mutagenesis to contain only one N-terminal or two C-terminal cysteine residues, respectively, thereby enabling covalent labeling with the fluorescent dye Atto 488 maleimide. We also had to render unstirred layer effects negligibly small. This was mainly achieved by reconstituting the purified aquaporins into vesicles that were only dV = 120 nm in diameter (7, 20, 21). Assuming that the width of the unstirred (stagnant water) layer wUL is comparable to vesicle size, and that the diffusion coefficient of bulk water DB is equal to 2.3 × 10–5 cm2 s–1, we find an unstirred layer water permeability PUL = DB/wUL ≈ 2 cm/s. Thus, even if Pf,c is 10 times larger than Pf,l = 20 μm/s, PUL exceeds Pf hundredfold. Because 1/Pa = 1/PUL + 1/Pf, the apparent (measured) water permeability Pa does not differ from Pf by more than 1%.

In the immediate membrane vicinity of bigger objects, wUL is so large in size that osmotic flow through them results in osmolyte dilution. If unaccounted for, the result is a severe underestimation of both Pf and pf (Eq. 2).

The small vesicle size led to the third problem: the assessment of changes in vesicle volume V from measurements of scattered light intensity I. Empirical approximations thus far used ranged from double logarithmic (22), over quadratic (23), to simple linear dependencies (24) of V from I. Here, we adopted the Rayleigh-Gans-Debye approximation and analytically solved the differential equation to calculate pf from the water efflux rate.

We determined the number n of aquaporin monomers per proteoliposome by FCS as previously described (25) and as exemplified in Fig. 1A (see also fig. S5). Depending on the preparation, n varied between 1 and 30. The reconstitution efficiency varied between 10 and 50% (fig. S6). At very low concentrations, AQP1 and GlpF reconstituted as functional monomers, dimers, or trimers. To enable comparison with AFM measurements, we calculated the expected number NO,FCS of oligomers per proteoliposome by assuming (i) a Poisson distribution of functional units among the proteoliposomes and (ii) that all units within one vesicle assembled into the smallest number of oligomers possible.

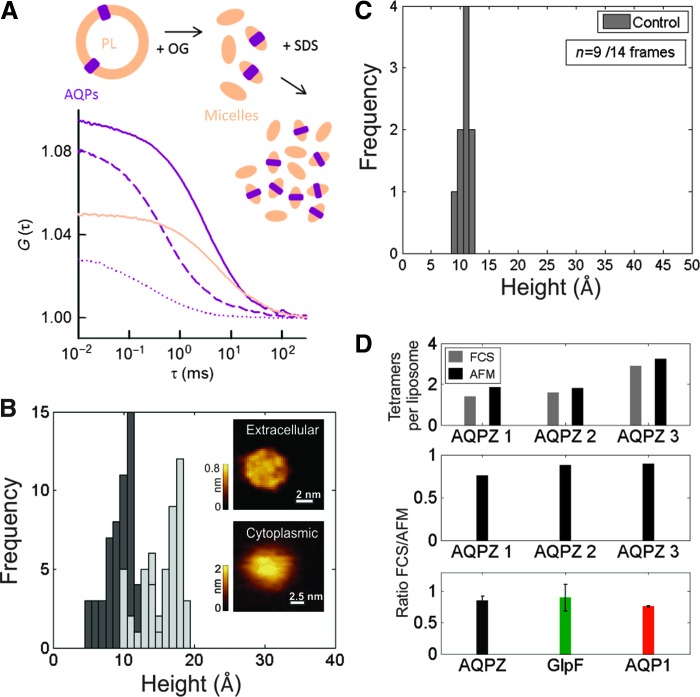

Fig. 1. Determination of reconstitution efficiency.

(A) FCS autocorrelation curves allowed us to obtain the number of (i) vesicles labeled with 0.004% (w/w) N-(lissamine-rhodamine-sulfonyl)phosphatidylethanolamine (sandy brown), (ii) AQP1-YFP–containing vesicles (purple), (iii) AQP1-YFP oligomers containing micelles that formed upon vesicle dissolution in mild detergent (dashed purple), and (iv) AQP1-YFP monomer containing micelles that formed upon further dissolution in harsh detergent (dotted purple) per confocal volume. The buffer (pH 7.4) contained 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Mops, and a protease inhibitor. (B and C) AFM imaging of solid-supported lipid bilayers that were prepared from AQPZ proteoliposomes (B) or empty vesicles (investigated area: 14 × 400 × 400nm2) (C) resulted in histograms of height values (n = 50). (B) Inset: The high-resolution raw data allowed differentiation of the extracellular and cytoplasmic AQPZ surfaces. (C) The density of unspecified features (0.218 per vesicle) served to correct the protein count (see also fig. S1). (D) Comparison of both the absolute AFM and FCS counts of AQPZ tetramers per liposome (at three different concentrations) (upper panel) and their ratio (middle panel). Average ratio of AFM and FCS counts per liposome for AQPZ, GlpF, and AQP1 oligomers (lower panel: compare also eqs. S9 and S10).

To confirm the FCS count, we performed additional measurements using high-speed AFM (HS-AFM) (26). In brief, we spread the vesicles on mica and imaged the resulting supported bilayers (Fig. 1, B to D). Initially, high-magnification raw data images were recorded and compared to the topography of the extracellular and cytoplasmic aquaporin surfaces known from previous studies of aquaporins reconstituted into two-dimensional crystals (27, 28). This enabled us to identify the extracellular and cytoplasmic surfaces of single aquaporins (Fig. 1B, inset) and to conclude that the aquaporins were reconstituted with random orientation (29). We generated a height histogram of the membrane-protruding parts with respect to the surrounding lipids by randomly taking 50 cross-sections of the protein surface. Subsequently, protein-free bilayers were spread on mica, and a second histogram of maximum height values (investigated area: 13 × 400 × 400 nm2) was constructed from the observed unspecified membrane-protruding features (Fig. 1C). Protein abundances per vesicle were determined for AQPZ, AQP1, and GlpF as exemplified for AQPZ in fig. S7. The comparison to NO,FCS was quite satisfactory. When repeating the procedure for at least three different protein concentrations of each of the aquaporins, HS-AFM always counted fc ≈ 1.2 times more particles than FCS (Fig. 1D).

Subsequently, we subjected the reconstituted vesicles to osmotic stress. V was determined by the vesicular water permeability Pf = Pf,l + Pf,c, which reflects the permeabilities Pf,c and Pf,l of all channels and the lipid bilayer, respectively:

| 3 |

where Vw, V0, A, , cs, and L are the molar volume of water, vesicle volume at time zero, surface area of the vesicle, the initial osmolyte concentration inside the vesicles, the incremental osmolyte concentration in the external solution due to sucrose addition, and the Lambert function L(x)eL(x) = x, respectively. V(t) is experimentally accessible by measuring I(t). To derive the corresponding expression, we exploited the Rayleigh-Gans-Debye relation (see the Supplementary Materials). We then substituted the dependence of the scattered light intensity on V for its Taylor series (figs. S1 and S2) and took into account the fraction α of bare vesicles, which does not contain any protein:

| 4 |

where VAQP(t) and Vbare(t) are the volumes of proteoliposomes and bare vesicles, respectively. The parameter a is calculated as follows: , where . The fitting parameters b and d can be found analytically (see the Supplementary Materials) so that Pf may remain as the sole fitting parameter. However, this rather laborious procedure returned the same Pf value as the simpler fitting approach, which simultaneously determined b, d, and Pf for all test cases. When fitting Eq. 4 to the stopped-flow data (Fig. 2A), we fixed Pf,l to its value in pure lipid vesicles.

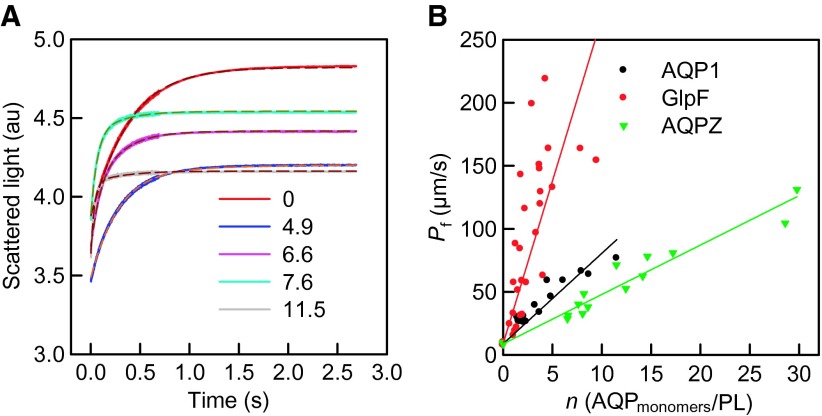

Fig. 2. The osmotic shrinkage of proteoliposomes.

(A) Representative stopped-flow raw data (spline lines) for AQPZ and the fit (dashed lines) according to Eq. 4. Equal volumes of vesicle suspension and hyperosmotic solution (300 mM sucrose) were mixed (5°C, same buffer as in Fig. 1). The number of reconstituted AQP monomers per proteoliposome is indicated. (B) Pf of reconstituted vesicles was calculated as shown in (A) for at least three independently purified and reconstituted batches for each protein and plotted as a function of the channel number per proteoliposome.

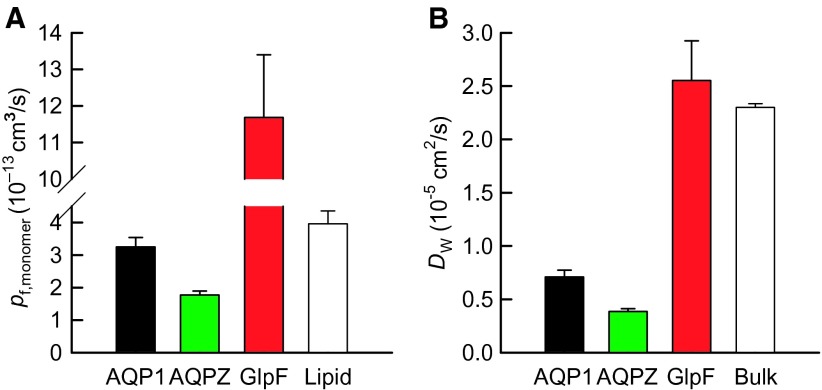

We performed the stopped-flow experiments for different numbers n of functional AQP units per vesicle (Fig. 2 and fig. S4) to determine pf (Fig. 3A) from the linear regression of Eq. 2. Because the measurements were made at 5°C, we used the known activation energy of ~4 kcal/mol (21, 30) to estimate pf at room temperature. DW (Eq. 1) decreased while NW increased from 4 in GlpF (10) to 7 in AQP1 and AQPZ (Fig. 3B). Our pf values exceeded previously reported ones, confirming that pf estimations from larger objects were subject to unstirred layer effects (15, 31) (see the Supplementary Materials). Our pf exceeds the in silico pf for AQPZ by a factor of 2 (11), that of AQP1 by a factor of 5 (32), and that of GlpF by a factor of 12 (9, 11).

Fig. 3. Water movement in aquaporins.

(A) pf (at 5°C) for AQPZ, GlpF, and AQP1 was taken from the slopes in Fig. 2B. The background water permeability of a single lipid vesicle was calculated by multiplying Pf,l by the surface area of the vesicle. (B) The diffusion coefficient DW (25°C) of water molecules inside the channel was calculated (Eq. 1). The bulk water diffusion coefficient is shown for comparison.

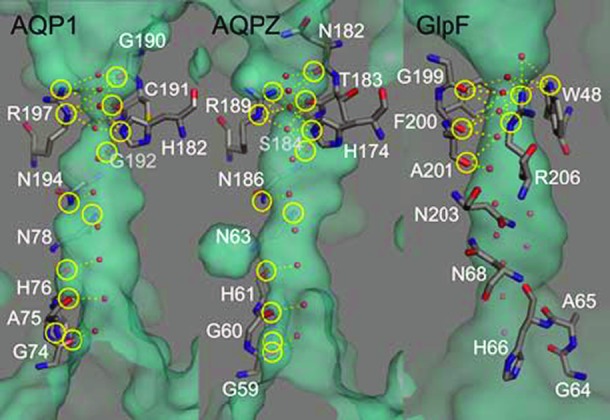

We took the 0.88-Å resolution structure of yeast AQP1 (33) as a template and used PyMol (34) to construct homology models for AQP1, AQPZ, and GlpF (fig. S8). We count NH = 12 possible hydrogen bonds between the single-file waters and pore-lining residues in the plot that shows the water-filled cavity (Fig. 4). The twofold lower pf of AQPZ may be caused by closings of AQPZ (35). To allow for the passage of the comparatively large glycerol molecules, the constriction site of GlpF is wider and shorter than that of the pure water channels AQP1 and AQPZ. In contrast to the glycerol-free crystal structure and its molecular dynamics simulation (16), more recent simulations found the length of the single-file region to be halved in GlpF (10, 11). In agreement with the more recent simulations, we find NH = 6 from the homology model (Fig. 4). Because the single-file region contains only a small number of binding places, it is not surprising that GlpF has the highest pf among the three aquaporins investigated.

Fig. 4. Number NH of pore-lining residues (in yellow circles) that may form hydrogen bonds (dotted lines) with single-file water molecules.

The 0.88-Å resolution structure of yeast AQP1 (33) [Protein Data Bank (PDB) #3Z0J] served as a template to find a model for the AQP1 (PDB #1J4N), AQPZ (PDB #1RC2), and GlpF (PDB #1FX8) structures via the PyMol’s “align” routine (34). The position of the water molecules (red spheres) is from the yeast AQP1 structure. The two water molecules below R206 have been added in the GlpF model to indicate that this region is wide enough to let the water molecules bypass each other within the pore.

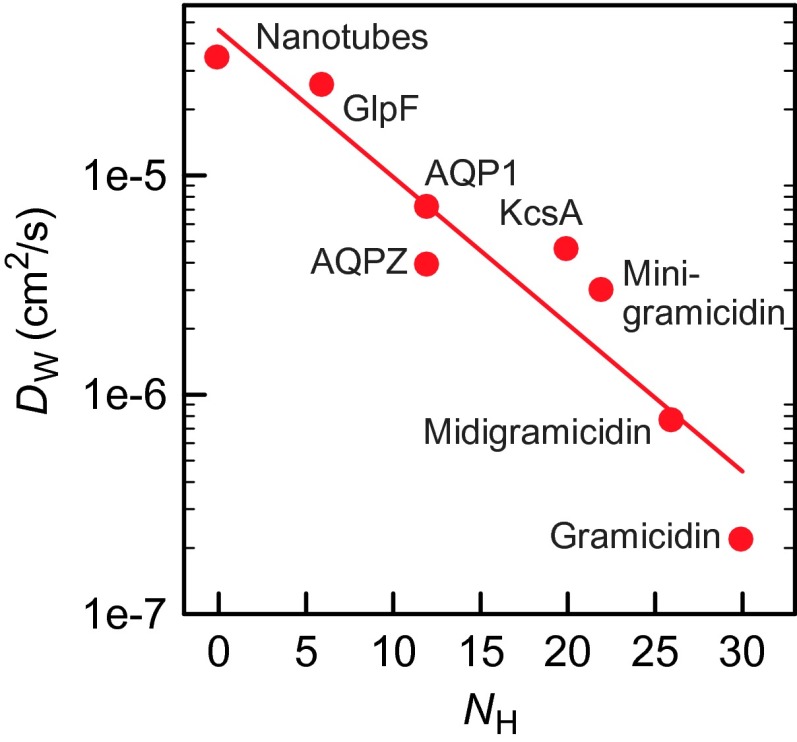

Plotting NH against DW reveals a logarithmic dependence (Fig. 5). This observation is reminiscent of the logarithmic length dependence described for gramicidin derivatives (17). Because gramicidin conducts the single-file waters within the helix, we assume that all 30 backbone carbonyls may form hydrogen bonds. Midigramicidin and minigramicidin are four and eight residues shorter, respectively, which reduce NH. Their DW (Eq. 1) fits into the logarithmic dependence (Fig. 4). Finally, we recalculated pf for the bacterial potassium channel KcsA by applying Eq. 4 to our previously published stopped-flow curves (18). The corresponding DW (Eq. 1) is in line with the assumption that all 20 filter carbonyls are capable of contributing to NH (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5. DW depends on the number NH of hydrogen bonds that single-file water molecules may form with pore-lining residues.

DW in nanotubes assumes z = 2.6 Å and k0 = 0.1 p s−1 (13). pf for the bacterial potassium channel KcsA was calculated by applying Eq. 4 to our previously published stopped-flow curves (18). Equation 1 served to compute DW from the pf values of gramicidin, midigramicidin, minigramicidin (17), and KcsA.

The logarithmic dependence reflects that the number of binding sites increases out of proportion to NH. A binding site in this sense represents a unique combination of the hydrogen bonds that any of the single-file water may form with pore-lining residues. If these residues are sparse, the binding sites are well-separated and their number coincides with NH. With increasing NH, there will be a spatial overlap between the binding sites. As a result, only a fraction of the available binding sites may be occupied simultaneously. This phenomenon has already been described for the yeast aquaporin: NH of its selectivity filter amounts to six. However, sterical hindrance prevents that the four resulting binding sites may accommodate more than two water molecules. Thus, the water molecules move pairwise through the filter (33), first occupying the first and third binding sites and then the second and fourth. In consequence, every water molecule must be released from a succession of two binding sites to traverse the distance that corresponds to its thickness.

Other single-file channels may have an even denser packing of binding sites. For example, gramicidin may accommodate only seven water molecules but its NH of 30 translates into a multitude of that number in terms of binding options. If all of them are satisfied with the same probability, and if each of the seven water molecules dwells at all binding sites for roughly the same time, a logarithmic increase of DW with NH is expected.

NH sets the limits for the maximal pf value of an open single-file pore. Thus, the functional relationship between pf and NH does not hold for channels that are capable of gating. For example, NH of AQP0 amounts to 16 (compare fig. S9) and not to 60, as may have been derived from its low pf ≈ 2.8 × 10−16 cm3 s−1 (36). The low pf may be due to the considerable amount of time that the AQP0 channel spends in its closed state: two Tyr residues (Y23 and Y149) may plug the channel [compare (37, 38) and fig. S9]. In addition, pf of AQP0 was reported to be increased by acidic pH (39, 40).

We conclude that in single-file transport, DW is not governed by channel geometry. Rather, the capability of the single-file waters to form hydrogen bonds to channel wall-lining residues causes the observed variability of two orders of magnitude. Other factors (for example, an increased penalty for entering the channel) may further reduce pf.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Hummer (Frankfurt, Germany) for a helpful discussion and Q. Beatty for editorial help. Funding: This work was supported by grants P23466 and P23679 of the Austrian Science Fund to P.P., the European Fund for Regional Development (Regio 13), and the Federal State of Upper Austria (to J.P.). S.A.A. gratefully acknowledges the financial support by both the Russian government (Goszadanie research project #3.2007.2014/K) and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation in the framework of MISiS Increase Competitiveness Program.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1400083/DC1

Fig. S1. The intensity I of scattered light for osmotically challenged vesicles as a function of vesicle radius R (A) and vesicle volume V (B).

Fig. S2. Comparison of the exact dependencies for I (red) with the approximate representations by their Taylor series (green) for R: I(t) = a + bR(t) + dR2(t) (A) or for V: I(t) = a + bV(t) + dV2(t) (B).

Fig. S3. Osmotically induced vesicle shrinkage was accompanied by an increase in I.

Fig. S4. Osmotic shrinkage of proteoliposomes.

Fig. S5. A typical FCS counting experiment of an AQP1-YFP reconstitution series.

Fig. S6. Reconstitution efficiency varied between 10 and 50%.

Fig. S7. Membrane protein detection by AFM.

Fig. S8. Alignments of aquaporin structures.

Fig. S9. Water-filled cavities in the open and closed structures of AQP0.

Table S1. Overview of published in vitro and in silico single-channel permeability values pf for AQP1, GlpF, and AQPZ as discussed in the main text.

References and Notes

- 1.A. Finkelstein, Water Movement Through Lipid Bilayers, Pores, and Plasma Membranes (Wiley & Sons, New York, 1987), pp. 1–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levitt D. G., Subramanian G., A new theory of transport for cell membrane pores. II. Exact results and computer simulation (molecular dynamics). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 373, 132–140 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raviv U., Laurat P., Klein J., Fluidity of water confined to subnanometre films. Nature 413, 51–54 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl P., Combined transport of water and ions through membrane channels. Biol. Chem. 385, 921–926 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heymann J. B., Engel A., Aquaporins: Phylogeny, structure, and physiology of water channels. News Physiol. Sci. 14, 187–193 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgnia M. J., Agre P., Reconstitution and functional comparison of purified GlpF and AqpZ, the glycerol and water channels from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2888–2893 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saparov S. M., Tsunoda S. P., Pohl P., Proton exclusion by an aquaglyceroprotein: A voltage clamp study. Biol. Cell 97, 545–550 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage D. F., O’Connell J. D. III, Miercke L. J. W., Finer-Moore J., Stroud R. M., Structural context shapes the aquaporin selectivity filter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17164–17169 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu F., Tajkhorshid E., Schulten K., Pressure-induced water transport in membrane channels studied by molecular dynamics. Biophys. J. 83, 154–160 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen M. Ø., Mouritsen O. G., Single-channel water permeabilities of Escherichia coli aquaporins AqpZ and GlpF. Biophys. J. 90, 2270–2284 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashido M., Kidera A., Ikeguchi M., Water transport in aquaporins: Osmotic permeability matrix analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 93, 373–385 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hummer G., Rasaiah J. C., Noworyta J. P., Water conduction through the hydrophobic channel of a carbon nanotube. Nature 414, 188–190 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berezhkovskii A., Hummer G., Single-file transport of water molecules through a carbon nanotube. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 064503 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu F. Q., Tajkhorshid E., Schulten K., Collective diffusion model for water permeation through microscopic channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 224501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walz T., Smith B. L., Zeidel M. L., Engel A., Agre P., Biologically active two-dimensional crystals of aquaporin CHIP. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 1583–1586 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tajkhorshid E., Nollert P., Jensen M. Ø., Miercke L. J., O’Connell J., Stroud R. M., Schulten K., Control of the selectivity of the aquaporin water channel family by global orientational tuning. Science 296, 525–530 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saparov S. M., Pfeifer J. R., Al-Momani L., Portella G., de Groot B. L., Koert U., Pohl P., Mobility of a one-dimensional confined file of water molecules as a function of file length. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 148101 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoomann T., Jahnke N., Horner A., Keller S., Pohl P., Filter gate closure inhibits ion but not water transport through potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10842–10847 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeidel M. L., Ambudkar S. V., Smith B. L., Agre P., Reconstitution of functional water channels in liposomes containing purified red cell CHIP28 protein. Biochemistry 31, 7436–7440 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saparov S. M., Kozono D., Rothe U., Agre P., Pohl P., Water and ion permeation of aquaporin-1 in planar lipid bilayers. Major differences in structural determinants and stoichiometry. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31515–31520 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pohl P., Saparov S. M., Borgnia M. J., Agre P., Highly selective water channel activity measured by voltage clamp: Analysis of planar lipid bilayers reconstituted with purified AqpZ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9624–9629 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Heeswijk M. P., van Os C. H., Osmotic water permeabilities of brush border and basolateral membrane vesicles from rat renal cortex and small intestine. J. Membr. Biol. 92, 183–193 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Illsley N. P., Verkman A. S., Serial permeability barriers to water transport in human placental vesicles. J. Membr. Biol. 94, 267–278 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Hoek A. N., Verkman A. S., Functional reconstitution of the isolated erythrocyte water channel CHIP28. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 18267–18269 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knyazev D. G., Lents A., Krause E., Ollinger N., Siligan C., Papinski D., Winter L., Horner A., Pohl P., The bacterial translocon SecYEG opens upon ribosome binding. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17941–17946 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preiner J., N. Kodera, J. Tang, A. Ebner, M. Brameshuber, D. Blaas, N. Gelbmann, H. J. Gruber, T. Ando, P. Hinterdorfer, IgGs are made for walking on bacterial and viral surfaces. Nat. Commun. 5, 4394 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheuring S., Ringler P., Borgnia M., Stahlberg H., Müller D. J., Agre P., Engel A., High resolution AFM topographs of the Escherichia coli water channel aquaporin Z. EMBO J. 18, 4981–4987 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Möller C., Fotiadis D., Suda K., Engel A., Kessler M., Müller D. J., Determining molecular forces that stabilize human aquaporin-1. J. Struct. Biol. 142, 369–378 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preiner J., A. Horner, A. Karner, N. Ollinger, C. Siligan, P. Pohl, P. Hinterdorfer, High-speed AFM images of thermal motion provide stiffness map of interfacial membrane protein moieties. Nano Lett. 15, 759–763 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathai J. C., Mori S., Smith B. L., Preston G. M., Mohandas N., Collins M., van Zijl P. C., Zeidel M. L., Agre P., Functional analysis of aquaporin-1 deficient red cells. The Colton-null phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1309–1313 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zampighi G. A., Kreman M., Boorer K. J., Loo D. D., Bezanilla F., Chandy G., Hall J. E., Wright E. M., A method for determining the unitary functional capacity of cloned channels and transporters expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 148, 65–78 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Groot B. L., Grubmuller H., Water permeation across biological membranes: Mechanism and dynamics of aquaporin-1 and GlpF. Science 294, 2353–2357 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosinska Eriksson U., Fischer G., Friemann R., Enkavi G., Tajkhorshid E., Neutze R., Subangstrom resolution X-ray structure details aquaporin-water interactions. Science 340, 1346–1349 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.W. L. DeLano, The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, 2002); www.pymol.org.

- 35.Jiang J., Daniels B. V., Fu D., Crystal structure of AqpZ tetramer reveals two distinct Arg-189 conformations associated with water permeation through the narrowest constriction of the water-conducting channel. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 454–460 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandy G., Zampighi G. A., Kreman M., Hall J. E., Comparison of the water transporting properties of MIP and AQP1. J. Membr. Biol. 159, 29–39 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonen T., Sliz P., Kistler J., Cheng Y. F., Walz T., Aquaporin-0 membrane junctions reveal the structure of a closed water pore. Nature 429, 193–197 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashido M., Ikeguchi M., Kidera A., Comparative simulations of aquaporin family: AQP1, AQPZ, AQP0 and GlpF. FEBS Lett. 579, 5549–5552 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nemeth-Cahalan K. L., Kalman K., Hall J. E., Molecular basis of pH and Ca2+ regulation of aquaporin water permeability. J. Gen. Physiol. 123, 573–580 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nemeth-Cahalan K. L., Clemens D. M., Hall J. E., Regulation of AQP0 water permeability is enhanced by cooperativity. J. Gen. Physiol. 141, 287–295 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1400083/DC1

Fig. S1. The intensity I of scattered light for osmotically challenged vesicles as a function of vesicle radius R (A) and vesicle volume V (B).

Fig. S2. Comparison of the exact dependencies for I (red) with the approximate representations by their Taylor series (green) for R: I(t) = a + bR(t) + dR2(t) (A) or for V: I(t) = a + bV(t) + dV2(t) (B).

Fig. S3. Osmotically induced vesicle shrinkage was accompanied by an increase in I.

Fig. S4. Osmotic shrinkage of proteoliposomes.

Fig. S5. A typical FCS counting experiment of an AQP1-YFP reconstitution series.

Fig. S6. Reconstitution efficiency varied between 10 and 50%.

Fig. S7. Membrane protein detection by AFM.

Fig. S8. Alignments of aquaporin structures.

Fig. S9. Water-filled cavities in the open and closed structures of AQP0.

Table S1. Overview of published in vitro and in silico single-channel permeability values pf for AQP1, GlpF, and AQPZ as discussed in the main text.