Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1)-specific dendritic cell (DC) vaccines have been used in clinical trials. However, they have been found to only induce some degree of immune responses in these studies. We previously demonstrated that the HIV-1 Gag-specific Gag-Texo vaccine stimulated Gag-specific effector CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses, leading to completely protective, but very limited, therapeutic immunity. In this study, we constructed a recombinant adenoviral vector, adenovirus (AdV)4-1BBL, which expressed mouse 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL), and generated transgenic 4-1BBL-engineered OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccines by transfecting ovalbumin (OVA)-Texo and Gag-Texo cells with AdV4-1BBL, respectively. We demonstrate that the OVA-specific OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates more efficient OVA-specific CTL responses (3.26%) compared to OVA-Texo-activated responses (1.98%) in wild-type C57BL/6 mice and the control OVA-Texo/Null vaccine without transgenic 4-1BBL expression, leading to enhanced therapeutic immunity against 6-day established OVA-expressing B16 melanoma BL6-10OVA cells. OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs, which have a CD44+CD62Lhigh IL-7R+ phenotype, are likely memory CTL precursors, demonstrating prolonged survival and enhanced differentiation into memory CTLs with functional recall responses and long-term immunity against BL6-10OVA melanoma. In addition, we demonstrate that OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs up- and downregulate the expression of anti-apoptosis (Bcl2l10, Naip1, Nol3, Pak7 and Tnfrsf11b) and pro-apoptosis (Casp12, Trp63 and Trp73) genes, respectively, by RT2 Profiler PCR array analysis. Importantly, the Gag-specific Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine also stimulates more efficient Gag-specific therapeutic and long-term immunity against HLA-A2/Gag-expressing B16 melanoma BL6-10Gag/A2 cells than the control Gag-Texo/Null vaccine in transgenic HLA-A2 mice. Taken together, our novel Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine, which is capable of stimulating potent Gag-specific therapeutic and long-term immunity, may represent a new immunotherapeutic vaccine for controlling HIV-1 infection.

Keywords: 4-1BBL, Gag, HLA-A2 mice, T cell-based vaccine, therapeutic immunity

Introduction

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are considered an important immune component for effective immunity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), and the induction of such responses using vaccines has become a major objective in the strategy to halt the pandemic.1,2 Dendritic cells (DCs), the most potent antigen-presenting cells, which express the HIV-1 structure proteins gp120 and Gag, have been used as vaccines and have been shown to stimulate HIV-1-specific CTL responses in animal models.3,4,5,6 However, HIV-1-specific DC vaccines have been found to only induce some degree of immune responses in clinical trials,7 warranting the search for other more efficient vaccine strategies.

We previously developed a novel T cell-based vaccine (ovalbumin (OVA)-Texo) using ConA-stimulated CD4+ T cells with the uptake of OVA-specific DC-released exosomes (EXOs).8,9,10 We demonstrated that the OVA-Texo vaccine induces more efficient immunity than the DC vaccine and is capable of stimulating potent CD4+ T cell-independent CTL responses and long-term antitumor immunity via IL-2/CD80 and CD40L signaling, counteracting regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression.8,9,10 In addition, we also developed HIV-1 gp120- and Gag-specific T cell-based (gp120-Texo and Gag-Texo) vaccines using ConA-stimulated mouse CD8+ T cells for the uptake of gp120- and Gag-specific DC-released EXOs.11,12,13 We demonstrated that gp120-Texo- and Gag-Texo-stimulated gp120- or Gag-specific CTL responses developed in transgenic HLA-A2 mice.11,12,13 However, the therapeutic efficacy of these vaccines was still very limited. For example, the gp120-Texo vaccine only cured 2/8 transgenic HLA-A2 mice bearing 6-day-established HLA-A2/gp120-expressing BL6-10Gp120/A2 B16 melanoma, although the vaccine cured 8/8 HLA-A2 mice bearing a 3-day-established tumor.11,12,13 The Gag-Texo vaccine could only induce some degree of therapeutic immunity, resulting in a decreased number and size of 6-day-established HLA-A2/Gag-expressing BL6-10Gag/A2 B16 melanomas in transgenic HLA-A2 mice.13

4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor family.14 It is inducible on activated antigen-presenting cells and can provide a CD28-independent signal leading to cell division, the induction of effector function and the enhancement of CD8+ T-cell survival and memory development.15,16,17,18,19 4-1BBL synergizes with CD80 and PD-1 blockade to re-activate anergic T cells20 and to augment CTL responses during chronic viral infection.21 In addition, 4-1BBL signaling is also a critical component in the costimulation-dependent rescue of exhausted HIV-specific CTLs,22 and the combination of 4-1BBL and CD40L signaling enhances the stimulation of HIV-1-specific CTLs.23 Therefore, 4-1BBL becomes an attractive candidate signaling molecule to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy.19 We assume that the incorporation of 4-1BBL into our Gag-Texo vaccine may enhance its therapeutic effect against Gag-expressing tumor cell challenge.

In this study, we generated transgenic 4-1BBL-engineered OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccines and assessed the OVA- and Gag-specific CTL responses and therapeutic and long-term immunity against OVA- and Gag-expressing B16 melanoma cells in vaccinated wild-type C57BL/6 and -transgenic HLA-A2 mice, respectively.

Materials and methods

Reagents, cell lines and animals

Biotin-labeled or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled antibodies (Abs) were obtained from BD Biosciences (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The Gag/HLA-A2-expressing BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cell line was generated by transfecting BL6-10 tumor cells with two expression vectors, pcDNANeoGag and pcDNAHygroHLA-A2, that express Gag and HLA-A2, respectively.13 Female C57BL/6 and transgenic (Tg) HLA-A2 mice (#003475) carrying the transgene Tg(HLA-A2.1)1Enge were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA, USA). All mice were treated according to the animal care committee guidelines of the University of Saskatchewan.

Recombinant adenovirus construction

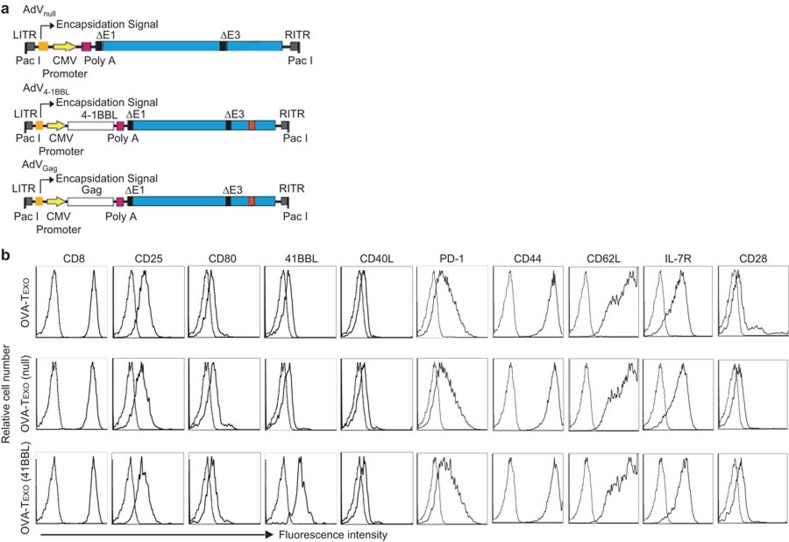

The construction of recombinant adenovirus (AdV) that expresses 4-1BBL (AdV4-1BBL) was performed by inserting the mouse 4-1BBL gene cloned from bone-marrow-derived DCs into a pShuttle vector (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), using the cloned 4-1BBL cDNA to form pLpA4-1BBL that expresses the 4-1BBL gene. The PmeI-digested shuttle vector was then co-transformed into BJ5183 Escherichia. coli cells already containing the backbone vector for homologous recombination to form the recombinant vector AdV4-1BBL, as described previously (Figure 1a).13 The adenoviral vector AdVGag, which expresses HIV-1 Gag, and the control AdVNull, without any transgenic expression, were previously constructed in our laboratory (Figure 1a).13

Figure 1.

Phenotypic analysis of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL. (a) Schematic representation of the AdV vectors AdVNull, AdVGag and AdV4-1BBL. The E1/E3-depleted, replication-deficient AdV is under the regulation of the CMV early/immediate promoter/enhancer. (b) The engineered OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo cells were stained with a panel of Abs (solid lines) or isotype-matched irrelevant Abs (dotted lines) and then analyzed by flow cytometry. One representative experiment of two is shown. Ab, antibody; AdV, adenoviral; 4-1BBL, 4-1BB ligand; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; OVA, ovalbumin.

Preparation of engineered OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccines

OVA- and Gag-specific OVA-Texo and Gag-Texo vaccines were generated by incubating ConA-activated CD8+ T (ConA-T) cells with OVA protein-pulsed bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCOVA)- and AdVGag-transfected DC (DCGag)-released exosomes (EXOOVA and EXOGag), as previously described.13 CD8± OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL or the control CD8± OVA-Texo/Null and Gag-Texo/Null vaccines were then generated by transfecting CD8± OVA-Texo and Gag-Texo cells with AdV4-1BBL or the control AdVNull, as previously described.13

Flow cytometry analysis

To assess CTL responses, blood samples from C57BL/6 mice i.v. immunized with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL or OVA-Texo/Null cells (2×106 cells/mouse) were taken 6 or 10 days after the immunization and were doubly stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 Ab (FITC-CD8) and PE-conjugated H-2Kb/OVA257–264 tetramer (PE-Tetramer) or triply stained with FITC-CD8 Ab, PE-tetramer and PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD44, CD62L and IL-7R Abs, respectively, and then analyzed by flow cytometry.8,9,10 To assess the intracellular expression of granzyme B and IFN-γ, splenocytes from immunized mice were stimulated with 2 µM OVAI (SIINFEKL) peptide in vitro in the presence of 2 µM monensin (GolgiStop, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for 4 h and then stained with a FITC-anti-CD8 antibody. The cells were then fixed, and the cell membranes were permeabilized in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and stained with a PE-anti-granzyme B antibody or a PE-anti-IFN-γ antibody for flow cytometry analysis.24 To assess recall responses, immunized mice were i.v. boosted with DCOVA (1×106 cells/mouse) 30 days after immunization. CTL responses were analyzed by flow cytometry. The absolute numbers of OVA-specific tetramer-positive CD8± T cells in each spleen of the immunized mice during the primary and recall responses were calculated as previously described.24

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed in immunized mice with the transfer of both OVA-specific CFSEhigh-labeled (H) and the control irrelevant CFSElow-labeled (L) target splenocytes at a ratio of 1∶1 (each 1×106 cells), as previously described.13 Sixteen hours after cell transfer, the residual CFSEhigh and CFSElow target cells remaining in the recipients' spleens were analyzed by flow cytometry.

RT2 profiler PCR array analysis

T cells were enriched from splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice immunized with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and OVA-Texo/Null vaccines using a nylon wool-column.8,9,10 OVA-specific CTLs were then purified from the enriched T-cell population using PE-tetramer staining followed by anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).25 A highly purified population of OVA-specific CTLs was obtained by passing the anti-PE microbeads-bound cell sample through a MACS column. The expression of a pathway-focused panel of 84 genes related to apoptosis in the above two groups of CTLs was examined using RT2 Profiler PCR Array Mouse Apoptosis (SuperArray Bioscience, Betheoda, MD).25

Animal studies

To examine the therapeutic antitumor immunity conferred by the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine, the wild-type C57BL/6 and transgenic HLA-A2 mice (n=8) were first injected i.v. with 0.5×106 BL6-10OVA and BL6-10Gag/A2 cells. Six days after tumor cell inoculation, C57BL/6 and HLA-A2 mice were then injected i.v. with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL cells (2×106 cells/mouse), respectively. OVA-Texo/Null and Gag-Texo/Null cells (2×106 cells/mouse) were used as vaccine controls. To assess the long-term antitumor immunity, C57BL/6 mice immunized with the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine and HLA-A2 mice immunized with the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine were i.v. challenged with a large dose of BL6-10OVA cells (1×106 cells/mouse) and a regular dose of BL6-10Gag/A2 cells (0.5×106 cells/mouse), respectively, 30 days after immunization. The mice were killed 3 weeks after tumor cell injection, and the lung metastatic tumor colonies were counted in a blind fashion. Metastases on freshly isolated lungs appeared as discrete black-pigmented foci that were easily distinguishable from normal lung tissues and confirmed by histological examination. Metastatic foci too numerous to count were assigned an arbitrary value of >300.9

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test for the comparison of variables from different groups. A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.10

Results

Generation of AdV4-1BBL-infected OVA-Texo (OVA-Texo/4-1BBL) vaccine expressing transgenic 4-1BBL

We first constructed a recombinant 4-1BBL-expressing adenoviral vector, AdV4-1BBL, by recombinant DNA technology (Figure 1a). We generated the OVA-Texo vaccine using ConA-stimulated CD8+ T cells to take up OVA-pulsed DC (DCOVA)-released EXOs (EXOOVA).11 We then generated the transgenic 4-1BBL-engineered and control OVA-Texo vaccines (OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and OVA-Texo/Null) by transfecting OVA-Texo cells with AdV4-1BBL and the control AdVNull, respectively, followed by a phenotypic assessment of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and OVA-Texo/Null by flow cytometry. We demonstrated that OVA-Texo/4-1BBL cells expressed a comparable amount of T-cell CD8, CD25, CD28, CD44, CD40L, CD62L, IL-7R, inhibitory PD-1 and exosomal costimulatory CD80, but an enhanced amount of costimulatory 4-1BBL compared to the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo cells (Figure 1b), indicating that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL cells express the transgene-encoded cell-surface 4-1BBL.

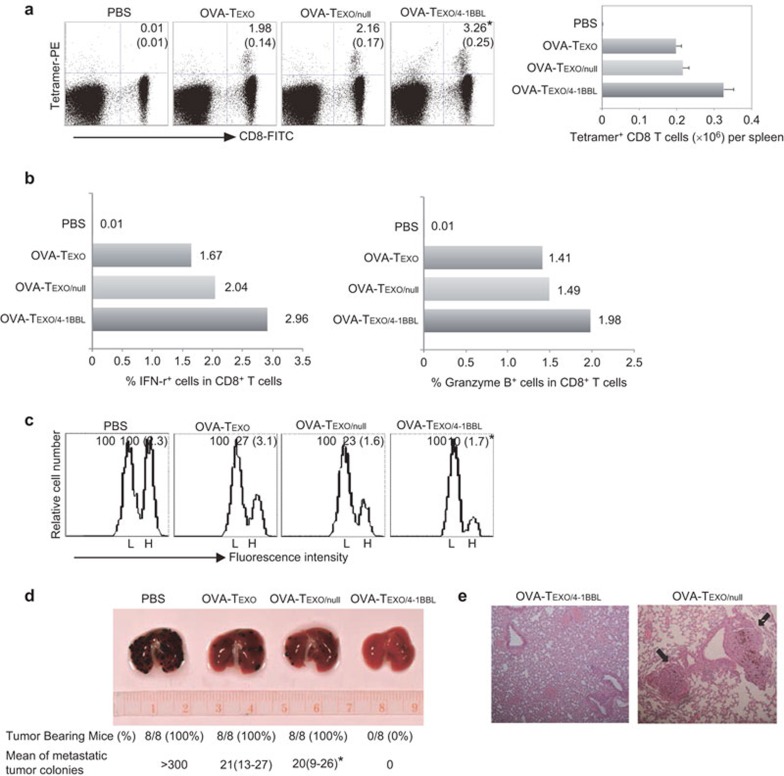

OVA-Texo/4-1BBL stimulates enhanced OVA-specific CD8+ effector CTL responses in wild-type C57BL/6 mice

To assess whether the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates enhanced CTL responses, we immunized wild-type C57BL/6 mice with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL and then assessed the OVA-specific CTL responses using FITC-CD8 and PE-tetramer antibody staining by flow cytometry. We demonstrated that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine was able to more efficiently stimulate OVA-specific CTL responses (3.26%, equivalent to 0.33×106 cells per spleen24) than the OVA-Texo vaccine (1.98%, equivalent to 0.20×106 cells per spleen) (P<0.05) (Figure 2a). To assess their phenotypes, the splenocytes of immunized mice were stimulated in vitro with OVAI peptide, and the CD8± T cells were examined for intracellular IFN-γ and Granzyme B expression using flow cytometry. We demonstrated that 2.69% and 1.98% of IFN-γ- and Granzyme B-expressing CD8± T cells, respectively, were found in the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-immunized mice (Figure 2b), which are more than those in either the OVA-Texo- or the OVA-Texo/Null-immunized mice. Next, we assessed the ability of the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine to induce the differentiation of stimulated CD8+ T cells into effector CTLs. We adoptively transferred OVA257–264 peptide-pulsed splenocytes that had been strongly labeled with CSFE (CFSEhigh), as well as the control peptide Mut1-pulsed splenocytes that had been weakly labeled with CFSE (CFSElow), into recipient mice that had been vaccinated with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL or OVA-Texo/Null. Thus, the loss of CFSEhigh target cells represents the killing activity of CTLs in immunized mice. As expected, there was substantial loss (90%) of the CFSEhigh (OVA peptide-pulsed) cells in the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-immunized mice, whereas significantly less cytotoxicity (77%) was induced in mice immunized with the control OVA-Texo/Null vaccine (P<0.05) (Figure 2c), indicating that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine efficiently stimulates OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell differentiation into functional effector CTLs with OVA-specific cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.

OVA-Texo/4-1BBL stimulates potent OVA-specific effector CTL responses and therapeutic immunity. (a) C57BL/6 mice (3–4 per group) were immunized with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL, OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo. Six days after immunization, tail blood samples from the immunized mice were stained with FITC-anti-CD8 Ab and PE-tetramer and then analyzed by flow cytometry. The value in each panel represents the percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T-cell population. The value in parentheses represents the s.d. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo groups (Student's t-test). (b) Intracellular staining. To assess the intracellular expression of granzyme B and IFN-γ, splenocytes from immunized mice were stimulated with OVAI peptide in vitro in the presence of monensin, followed by FITC-anti-CD8 antibody staining. After permeabilization, the cells were further stained with a PE-anti-granzyme B antibody or a PE-anti-IFN-γ antibody. CD8-positive T cells were gated for the assessment of granzyme B and IFN-γ expression by flow cytometry. (c) In vivo cytotoxicity assay. Six days after immunization, the immunized mice (3–4 per group) were i.v. injected with a mixture of CFSEhigh- and CFSElow-labeled splenocytes (at a 1∶1 ratio) that had been pulsed with OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL) peptide and the control Mut1 (FEQNTAQP) peptide of an irrelevant 3LL lung carcinoma antigen, respectively. After 16 h, the spleens of immunized mice were removed, and the percentages of the residual CFSEhigh (H) and CFSElow (L) target cells remaining in the recipients' spleens were analyzed by flow cytometry. The value in each panel represents the percentage of CFSEhigh vs. CFSElow target cells remaining in the spleen. The value in parentheses represents the s.d. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo groups (Student's t-test). (c) C57BL/6 mice (eight per group) were first i.v. injected with BL6-10OVA tumor cells (0.5×106 cells/mouse) followed by immunization of the mice with OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo/4-1BBL (2×106 cells/mouse) for the assessment of therapeutic immunity against 6-day-established tumors. The mice were killed 3 weeks after tumor cell challenge. The numbers of black lung metastatic tumor colonies were counted. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL group (Mann–Whitney U test). (d) H&E staining of the lung tissues. The lung tissues of immunized mice were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with H&E and examined by microscopy. Tumor colonies are marked with arrows. Magnification, ×150. One representative experiment of two is shown. Ab, antibody; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; OVA, ovalbumin; s.d., standard deviation.

The OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates enhanced therapeutic immunity against OVA-expressing BL6-10OVA melanoma in wild-type C57BL/6 mice

To assess the potential therapeutic effect of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL, we first challenged wild-type C57BL/6 mice with BL6-10OVA tumor cells. Six days after tumor cell challenge, mice bearing 6-day-established tumors were then immunized with OVA-Texo/4-1BBL. We demonstrated that both the OVA-Texo/Null and the OVA-Texo vaccines were able to significantly reduce the average number of lung tumor metastatic colonies (P<0.05) compared to the control mice with PBS injection, although they failed at curing any mice bearing 6-day-established tumors (Figure 2d). However, the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine was able to cure 8/8 mice (Figure 2d), indicating that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine induces an excellent therapeutic immunity against 6-day-established lung tumor metastasis in C57BL/6 mice. The presence and absence of lung tumor metastatic colonies in OVA-Texo/Null- and OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-immunized mouse lungs were confirmed by histopathologic analysis (Figure 2e).

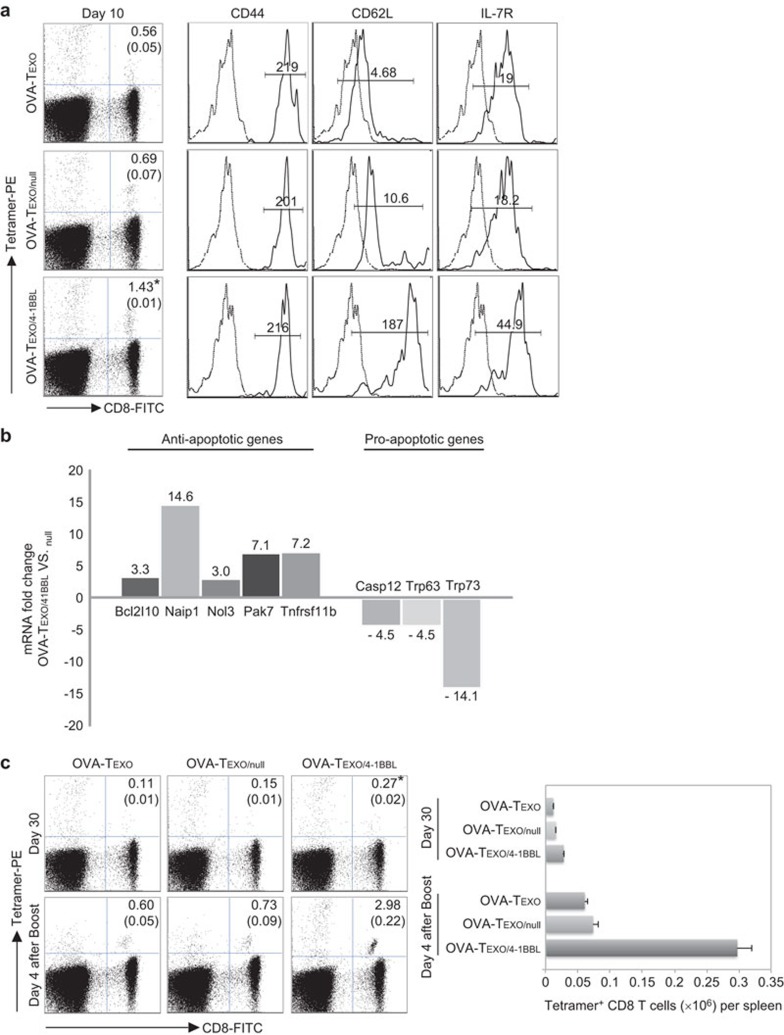

OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CD8+ T cells are likely CD62LhighIL-7R+ memory CTL precursors

To assess the phenotypic characteristics of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CD8+ T cells, we first gated OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-, OVA-Texo/Null- or OVA-Texo-stimulated CD8+ T cells for further analysis of the expression of CD44, CD62L and IL-7R 10 days after immunization. We demonstrated that all vaccine-stimulated CD8+ T cells expressed these molecules 10 days after immunization (Figure 3a). However, OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CD8+ T cells had a higher amount of CD62L and IL-7R expression than OVA-Texo/Null- or OVA-Texo-stimulated CD8+ T cells, indicating that they are likely CD62LhighIL-7R+ memory CTL precursors.26

Figure 3.

Characterization of OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs. (a) The tail blood samples were harvested from the immunized C57BL/6 mice 10 days after immunization and triply stained with FITC-anti-CD8 and PE-tetramer and PE-Cy5-anti-CD44, CD62L and IL-7RAb for flow cytometric analysis. The value in each panel represents the percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T-cell population. The value in parentheses represents thes.d. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo groups (Student's t-test). OVA-specific CD8+tetramer+ CTLs were sorted for the assessment of CD44, CD62L and IL-7R expression by flow cytometry (solid lines). Irrelevant isotype-matched Abs were used as controls (dotted lines). (b) An apoptosis RT-PCR array was performed to compare apoptosis-related gene expression differences between OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated and OVA-Texo/Null-stimulated CTLs. Total RNA was isolated from purified OVA-specific CTLs using an RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Missisauga, Ontario, Canada) and reversely transcribed using an RT2 First Strand kit (SuperArray Bioscience). The mRNA expression of each gene in the array system was performed using a StepOnePlus thermocycler (Applied Biosystem, BioRad, Missisauga, Ontario, Canada) and analyzed using Hprt1, Gapdh and β-actin as internal controls in web-based software per the manufacturer's instructions. Only genes with mRNA changes greater than threefold are shown. (c) Recall responses. The tail blood samples were harvested from the immunized C57BL/6 mice 30 days after immunization or 4 days after the boost and then doubly stained with FITC-anti-CD8 and PE-tetramer for flow cytometric analysis. The value in each panel represents the percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T-cell population. The value in parentheses represents the s.d. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo groups on day 30 after immunization or day 4 after the boost (Student's t-test). One representative experiment of two is shown. Ab, antibody; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; OVA, ovalbumin; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; s.d., standard deviation.

OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CD8+ T cells display up- and downregulation of anti- and pro-apoptosis genes, respectively

To assess the expression of anti- and pro-apoptosis genes, we extracted RNA from mouse OVA-specific CTLs purified from the immunized mouse splenic T-cell population, using an RNeasy extraction kit, 10 days after immunization. Apoptosis real-time PCR arrays were then performed to compare apoptosis-related gene expression between OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated and OVA-Texo/Null-stimulated CTLs using their RNA samples and the RT2 Profiler PCR Array Mouse Apoptosis kit. We demonstrated that anti-apoptosis-related genes, such as Bcl2l10 (3.3-fold), Naip1 (14.6-fold), Nol3 (3.0-fold), Pak7 (7.1-fold) and Tnfrsf11b (7.2-fold), were found to be upregulated in OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs compared to OVA-Texo/Null-stimulated CTLs (Figure 3b). In contrast, pro-apoptosis-related genes, such as Casp12 (−4.5-fold), Trp63 (−4.5-fold) and Trp73 (−14.1-fold), were found to be down-regulated in OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs (Figure 3b). Our results indicate that compared to OVA-Texo/Null-stimulated CTLs, OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs up- and downregulate the expression of anti- and pro-apoptosis related genes, respectively.

The OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates enhanced long-term immunity against OVA-expressing BL6-10OVA melanoma in wild-type C57BL/6 mice

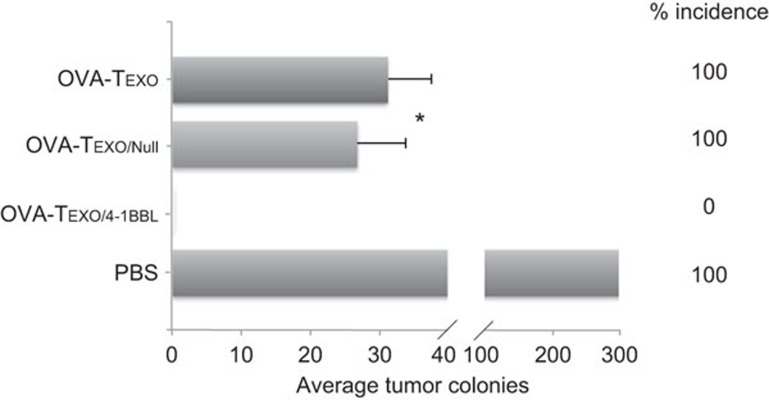

To assess whether OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CD8+ T cells differentiate into memory CD8+ T cells, we harvested blood samples from immunized C57BL/6 mice 30 days after the primary immunization, when OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated effector CD8+ T cells should become memory CD8+ T cells. We then stained the blood samples with a FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 Ab and PE-conjugated H-2Kb/OVA257–264 tetramer and then analyzed the cells by flow cytometry. We demonstrated that CD8+ T cells (0.27%) in the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-vaccinated group became memory CD8+ T cells, which are significantly more than those in the OVA-Texo/Null-vaccinated group (0.15%) (P<0.05) (Figure 3c). To assess whether these memory CD8+ T cells are functional, we then i.v. boosted the immunized mice with DCOVA cells 30 days after the primary immunization. Four days after the boost, we assessed the OVA-specific CTL responses by flow cytometry. We demonstrated that more recall responses (2.98%, equivalent to 0.30×106 cells per spleen) were observed in the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-vaccinated group than in the OVA-Texo/Null-immunized group (0.73%, equivalent to 0.07×106 cells per spleen) (P<0.05) (Figure 3c), indicating that OVA-specific CTLs in the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-vaccinated group increase by fourfold compared with those in the OVA-Texo/Null-vaccinated group after the boost stimulation. To assess the potential long-term protective immunity, we also i.v. challenged the immunized mice with BL6-10OVA tumor cells 30 days after the primary immunization, when vaccine-stimulated CTLs should have become memory CTLs. We demonstrated that OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-immunized, but not OVA-Texo/Null- or OVA-Texo-immunized, C57BL/6 mice obtained long-term immunity efficiently against challenge with a large dose of BL6-10OVA tumor cells (1×106/mouse) in 8/8 mice (Figure 4), indicating that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine also induces enhanced long-term immunity against OVA-expressing BL6-10OVA tumors in C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 4.

The OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates efficient long-term immunity in C57BL/6 mice. To assess long-term immunity, C57BL/6 mice (eight per group) were first i.v. immunized with OVA-Texo, OVA-Texo/Null and OVA-Texo/4-1BBL (2×106 cells/mouse). Thirty days after vaccination, mice were then i.v. injected with a large dose of OVA-expressing BL6-10OVA tumor cells (1×106 cells/mouse). The mice were killed 3 weeks after tumor cell challenge. The numbers of black lung metastatic tumor colonies were counted. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control PBS group (Mann–Whitney U test). One representative experiment of two is shown.

The Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine induces enhanced preventive, therapeutic and long-term immunity against Gag/HLA-A2-expressing BL6-10Gag/A2 melanoma in transgenic HLA-A2 mice

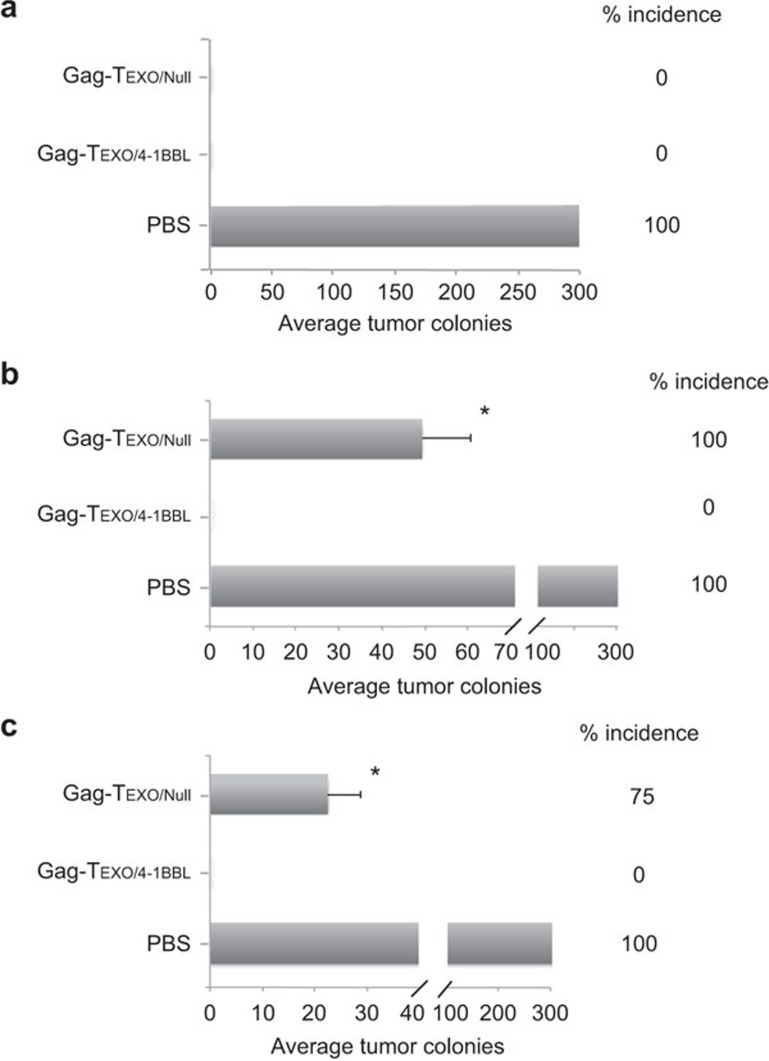

To assess preventive immunity, we first immunized transgenic HLA-A2 mice with Gag-Texo/4-1BBL or Gag-Texo/Null followed by challenging the immunized mice with HLA-A2/Gag-expressing BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells 6 days after immunization. We demonstrated that both the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL and the Gag-Texo/Null vaccines were able to protect all 8/8 mice from tumor challenge (Figure 5a), indicating that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates potent preventive immunity. To assess the potential therapeutic effect of Gag-Texo/4-1BBL, we first challenged transgenic HLA-A2 mice with BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells. Six days after tumor cell challenge, the mice were then immunized with Gag-Texo/4-1BBL or Gag-Texo/Null. We demonstrated that the Gag-Texo/Null vaccine was able to significantly reduce the average number of lung tumor metastatic colonies (P<0.05) compared to the control mice with PBS injection, but it failed at curing any mice bearing 6-day-established tumors (Figure 5b). However, the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine was still able to cure 8/8 mice (Figure 5b), indicating that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates potent therapeutic immunity. Next, we assessed long-term immunity by challenging immunized mice with a regular dose of BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells (0.5×106/mouse) 30 days after immunization. We demonstrated that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine but not the Gag-Texo/Null vaccine was able to protect all 8/8 mice from tumor challenge 30 days after immunization, although the Gag-Texo/Null vaccine significantly reduced the average number of lung tumor metastatic colonies (P<0.05) compared to the control mice with PBS injection (Figure 5c), indicating that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine also stimulates efficient long-term immunity in HLA-A2 mice.

Figure 5.

The Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates potent immunity in transgenic HLA-A2 mice. (a) Transgenic HLA-A2 mice (eight per group) were first i.v. immunized with Gag-Texo/Null and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL (2×106 cells/mouse) followed by the i.v. injection of HLA-A2/Gag-expressing BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells (0.5×106 cells/mouse) 6 days after immunization for the assessment of preventive immunity. (b) Transgenic HLA-A2 mice (eight per group) were first i.v. injected with BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells (0.5×106 cells/mouse) followed by the immunization of the mice with Gag-Texo/Null and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL (2×106 cells/mouse) for the assessment of therapeutic immunity against 6-day-established tumors. (c) HLA-A2 mice (eight per group) were first i.v. immunized with Gag-Texo/Null and Gag-Texo/4-1BBL (2×106 cells/mouse) followed by the i.v. injection of BL6-10Gag/A2 tumor cells (0.5×106 cells/mouse) 30 days after immunization for the assessment of long-term immunity. The mice were killed 3 weeks after tumor cell challenge. The numbers of black lung metastatic tumor colonies were counted. *P<0.05 versus cohorts of the control PBS group (Mann–Whitney U test). One representative experiment of two is shown.

Discussion

We previously developed a novel OVA-specific T cell-based vaccine (OVA-Texo) capable of stimulating efficient CTL responses and protective immunity by counteracting regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression and by inducing long-term antitumor immunity via IL-2/CD80 and CD40L signaling.8,9,10 To assess its therapeutic effect, C57BL/6 mice bearing 6-day-established OVA-expressing B16 melanoma BL6-10OVA tumors were immunized with OVA-Texo in this study. We demonstrate that the OVA-Texo vaccine is unable to cure any mice bearing 6-day tumors, although OVA-Texo vaccination significantly reduces the average number of lung tumor colonies compared to the PBS control. To improve its therapeutic efficacy, we generated an engineered OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine that expresses transgenic 4-1BBL. We demonstrate that the OVA-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates more efficient OVA-specific effector CTL responses, leading to potent therapeutic immunity and curing 8/8 C57BL/6 mice bearing 6-day-established BL6-10OVA melanoma. In addition, we also demonstrate that OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated CTLs are more likely to be memory CTL precursors, with preferential differentiation into CD44±CD62LhighIL-7R± central memory CTLs.26 Furthermore, OVA-Texo/4-1BBL-stimulated mice demonstrated enhanced recall responses and more efficient long-term immunity against a large dose challenge of OVA-expressing B16 melanoma BL6-10OVA cells.

Several apoptosis-related molecules that play key roles in regulating apoptosis in T cells have been identified,27,28 including the Bcl-2 family, with either anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic effects. It has been reported that 4-1BBL signaling promotes the survival of CD8+ T cells via 4-1BB-mediated NF-κB activation, leading to the upregulation of Bcl-XL and Bfl-1,17 and inhibits T-cell apoptosis via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–AKT/protein kinase B-mediated upregulation of Bcl-XL and c-FLIPshort.29 Recently, it has been shown that 41BB signaling enhances T-cell survival via the cooperation of tumor-necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-1 (TNFR1) and leukocyte-specific protein-1, leading to the activation of ERK and Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell-death.30 In this study, we demonstrated that 4-1BBL signaling up- and downregulated the expression of anti-apoptosis (Bcl2l10, Naip1, Nol3, Pak7 and Tnfrsf11b) and pro-apoptosis (Casp12, Trp63 and Trp73) genes, respectively, in CD8+ CTLs with prolonged survival. It has also been reported that 4-1BBL can interact with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to sustain TNF production.31 Active CD8+ T cells express TLRs, and TLR signaling has been shown to play a role in T-cell survival independently of antigen-presenting cells.32,33,34 TNF receptor-2 (TNFR2) is also present on active CD8+ T cells, and the TNF/TNFR2 interaction is important for sustaining their survival.35,36 Therefore, it is possible that the transgenic 4-1BBL expression on OVA-Texo/4-1BBL cells interacts with the TLRs of CD8+ T cells, leading to the enhanced TNF production and prolonged survival of activated CD8+ T cells via TLR signaling. Enhanced TNF production may also induce the prolonged survival of activated CD8+ T cells via its autocrine TNF/TNFR2 loop.35,36

The Gag vaccine has been shown to stimulate persistent and broader HIV-1-specific CTL responses against conserved Gag epitopes in animal models.37,38,39,40 HLA-B57 HIV-1-infected individuals have been found to have autologous CTL responses against four conserved Gag epitopes, leading to reduced virus replication and viral control.41 In addition, clinically, effective CTL responses against Gag, but not other viral antigens, have been found to correlate with a significant suppression of HIV-1 replication in patients.42,43,44,45 We have recently generated a Gag-specific, exosome-targeted Gag-Texo vaccine and demonstrated that Gag-Texo could stimulate Gag-specific CTL responses, but only induced some degree of therapeutic immunity against Gag/HLA-A2-expressing B16 melanoma BL6-10Gag/A2 cells in transgenic HLA-A2 mice.13 To improve its vaccination efficacy, we incorporated 4-1BBL into the Gag-Texo vaccine to generate an engineered Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine that expresses transgene 4-1BBL. We demonstrate that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine stimulates potent preventive immunity, leading to the protection of 8/8 transgenic HLA-A2 mice from challenge with BL6-10Gag/A2, and induces potent therapeutic immunity, leading to curing 8/8 transgenic HLA-A2 mice bearing 6-day-established BL6-10Gag/A2 tumors. In addition, the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine also induces an enhanced long-term immunity against BL6-10Gag/A2 challenge in transgenic HLA-A2 mice. Because HIV-1-specific CTLs are essential for effective immunity against HIV-1,1,2 Gag-Texo-stimulated Gag-specific CTLs, which have cytolytic effects against Gag-expressing tumor cells in HLA-A2 mice in this study, should also play important roles in controlling HIV-1 infection by their cytolytic effects against virus-infected T cells or DCs in HIV-1 patients. The assessment of Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccination efficacy at controlling Gag-specific viral infection in wild-type C57BL/6 mice infected by a recombinant replication-competent poxvirus rTTV-luc-gag expressing Gag 46 is underway in our laboratory.

In this study, we also demonstrated that the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL-vaccinated cells express PD-1, which was originally reported to be a T-cell activation antigen 47 and was later found to be an inhibitory regulator, promoting immune exhaustion48 and suppressing T-cell responses.49,50 PD-1 blockade with its antibody could restore T-cell function.51 It has been reported that the HIV-1 early regulatory protein Tat can broaden T-cell responses to HIV-1 envelope proteins.52,53 To enhance the therapeutic efficacy of the Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine, the construction and the assessment of a Gag-Tat-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine expressing both late HIV-1 Gag and early HIV-1 Tat proteins and the examination of Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccinated cells with PD-1 blocked by anti-PD-1 antibody in our transgenic HLA-A2 mouse model are also underway in our laboratory.

Taken together, our novel engineered Gag-Texo/4-1BBL vaccine, which is capable of stimulating potent therapeutic and long-term immunity, may represent a new immunotherapeutic vaccine for controlling HIV-1 infection.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grants (OCH 126276) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Beijing Science and Technology Foundation (5121002).

References

- McMichael A, Hanke T. The quest for an AIDS vaccine: is the CD8+ T-cell approach feasible. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:283–291. doi: 10.1038/nri779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd PA, Martins MA, Ericsen AJ, Tully DC, Power KA, Bean AT, et al. Vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells control AIDS virus replication. Nature. 2012;491:129–133. doi: 10.1038/nature11443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenta C, Santini SM, Logozzi M, Spada M, Andreotti M, Di Pucchio T, et al. Potent immune response against HIV-1 and protection from virus challenge in hu-PBL-SCID mice immunized with inactivated virus-pulsed dendritic cells generated in the presence of IFN-alpha. J Exp Med. 2003;198:361–367. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Tanaka R, Murakami T, Takahashi Y, Koyanagi Y, Nakamura M, et al. Induction of protective immune responses against R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice by intrasplenic immunization with HIV-1-pulsed dendritic cells: possible involvement of a novel factor of human CD4+ T-cell origin. J Virol. 2003;77:8719–8728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8719-8728.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villamide-Herrera L, Ignatius R, Eller MA, Wilkinson K, Griffin C, Mehlhop E, et al. Macaque dendritic cells infected with SIV-recombinant canarypox ex vivo induce SIV-specific immune responses in vivo. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:871–884. doi: 10.1089/0889222041725136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneil C, Aouba A, Burgard M, Cardinaud S, Rouzioux C, Langlade-Demoyen P, et al. Dendritic cells generated in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and IFN-alpha are potent inducers of HIV-specific CD8 T cells. AIDS. 2003;17:1731–1740. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200308150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia F, Routy JP. Challenges in dendritic cells-based therapeutic vaccination in HIV-1 infection Workshop in dendritic cell-based vaccine clinical trials in HIV-1. Vaccine. 2011;29:6454–6463. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Liu Y, Yuan J, Zhang X, He T, Wu X, et al. Novel exosome-targeted CD4+ T cell vaccine counteracting CD4+25+ regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression and stimulating efficient central memory CD8+ CTL responses. J Immunol. 2007;179:2731–2740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Yuan J, Xiang J. Nonspecific CD4+ T cells with uptake of antigen-specific dendritic cell-released exosomes stimulate antigen-specific CD8+ CTL responses and long-term T cell memory. J Leuk Biol. 2007;82:829–838. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Wang L, Freywald A, Qureshi M, Chen Y, Xiang J. A novel T cell-based vaccine capable of stimulating long-term functional CTL memory against B16 melanoma via CD40L signaling. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:72–77. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundappa RH, Wang R, Xie Y, Umeshappa CS, Chibbar R, Wei Y, et al. GP120-specific exosome-targeted T cell-based vaccine capable of stimulating DC- and CD4+ T-independent CTL responses. Vaccine. 2011;29:3538–3547. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundappa RH, Wang R, Xie Y, Umeshappa CS, Xiang J. Novel CD8+ T cell-based vaccine stimulates Gp120-specific CTL responses leading to therapeutic and long-term immunity in transgenic HLA-A2 mice. Vaccine. 2012;30:3519–3525. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Xie Y, Zhao T, Tan X, Xu J, Xiang J. HIV-1 Gag-specific exosome-targeted T cell-based vaccine stimulates effector CTL responses leading to therapeutic and long-term immunity against Gag/HLA-A2-expressing B16 melanoma in transgenic HLA-A2 mice. Trials Vaccinol. 2014;3:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Lin GH, McPherson AJ, Watts TH. Immune regulation by 4-1BB and 4-1BBL: complexities and challenges. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:192–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi C, Mittler RS, Vella AT. Cutting edge: 4-1BB is a bona fide CD8 T cell survival signal. J Immunol. 1999;162:5037–5040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EM, Lau P, Watts TH. Temporal segregation of 4-1BB versus CD28-mediated costimulation: 4-1BB ligand influences T cell numbers late in the primary response and regulates the size of the T cell memory response following influenza infection. J Immunol. 2002;168:3777–3785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Park SJ, Choi BK, Kim HH, Nam KO, Kwon BS. 4-1BB promotes the survival of CD8+ T lymphocytes by increasing expression of Bcl-xL and Bfl-1. J Immunol. 2002;169:4882–4888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulle G, Vidric M, Watts TH. IL-15-dependent induction of 4-1BB promotes antigen-independent CD8 memory T cell survival. J Immunol. 2006;176:2739–2748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes TJ, Lin GH, Wen T, Watts TH. Incorporation of 4-1BB ligand into an adenovirus vaccine vector increases the number of functional antigen-specific CD8 T cells and enhances the duration of protection against influenza-induced respiratory disease. Vaccine. 2011;29:6301–6312. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib-Agahi M, Phan TT, Searle PF. Co-stimulation with 4-1BB ligand allows extended T-cell proliferation, synergizes with CD80/CD86 and can reactivate anergic T cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19:1383–1394. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezys V, Penaloza-MacMaster P, Barber DL, Ha SJ, Konieczny B, Freeman GJ, et al. 4-1BB signaling synergizes with programmed death ligand 1 blockade to augment CD8 T cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:1634–1642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wen T, Routy JP, Bernard NF, Sekaly RP, Watts TH. 4-1BBL induces TNF receptor-associated factor 1-dependent Bim modulation in human T cells and is a critical component in the costimulation-dependent rescue of functionally impaired HIV-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:8252–8263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keersmaecker B, Heirman C, Corthals J, Empsen C, van Grunsven LA, Allard SD, et al. The combination of 4-1BBL and CD40L strongly enhances the capacity of dendritic cells to stimulate HIV-specific T cell responses. J Leuk Biol. 2011;89:989–999. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0810466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Hao S, Chan T, Xiang J. CD4+ T cells stimulate memory CD8+ T cell expansion via acquired pMHC I complexes and costimulatory molecules, and IL-2 secretion. J Leuk Biol. 2006;80:1354–1363. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeshappa CS, Xie Y, Xu S, Nanjundappa RH, Freywald A, Deng Y, et al. Th cells promote CTL survival and memory via acquired pMHC-I and endogenous IL-2 and CD40L signaling and by modulating apoptosis-controlling pathways. PloS One. 2013;8:e64787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois L, Obar JJ. Once a killer, always a killer: from cytotoxic T cell to memory cell. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:206–218. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmell JC, Thompson CB. The central effectors of cell death in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:781–828. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SY, Garban HJ. Regulation of apoptosis-related genes by nitric oxide in cancer. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starck L, Scholz C, Dorken B, Daniel PT. Costimulation by CD137/4-1BB inhibits T cell apoptosis and induces Bcl-xL and c-FLIP(short) via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and AKT/protein kinase B. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1257–1266. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh L, Andreeva D, Laramee GD, Oussa NA, Lew D, Bisson N, et al. Leukocyte-specific protein 1 links TNF receptor-associated factor 1 to survival signaling downstream of 4-1BB in T cells. J Leuk Biol. 2013;93:713–721. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Kim SO, Shimada S, Otsuka M, Seit-Nebi A, Kwon BS, et al. Cell surface 4-1BBL mediates sequential signaling pathways ‘downstream' of TLR and is required for sustained TNF production in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:601–609. doi: 10.1038/ni1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman AE, Zhang J, Choi Y, Turka LA. Toll-like receptor ligands directly promote activated CD4+ T cell survival. J Immunol. 2004;172:6065–6073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottalorda A, Verschelde C, Marcais A, Tomkowiak M, Musette P, Uematsu S, et al. TLR2 engagement on CD8 T cells lowers the threshold for optimal antigen-induced T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1684–1693. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley M, Martinez J, Huang X, Yang Y. A critical role for direct TLR2–MyD88 signaling in CD8 T-cell clonal expansion and memory formation following vaccinia viral infection. Blood. 2009;113:2256–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzascia T, Pellegrini M, Hall H, Sabbagh L, Ono N, Elford AR, et al. TNF-alpha is critical for antitumor but not antiviral T cell immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3833–3845. doi: 10.1172/JCI32567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Priatel JJ, Teh SJ, Teh HS. TNF receptor type 2 (p75) functions as a costimulator for antigen-driven T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;176:1026–1035. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SD, Rottinghaus ST, Zajac AJ, Yue L, Hunter E, Whitley RJ, et al. HIV-1(89.6) Gag expressed from a replication competent HSV-1 vector elicits persistent cellular immune responses in mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:6764–6773. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li S, Hu Y, Tang B, Cui L, He W. Efficient augmentation of a long-lasting immune responses in HIV-1 gag DNA vaccination by IL-15 plasmid boosting. Vaccine. 2008;26:3282–3290. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu L, Termini JM, Kanagavelu SK, Gupta S, Rolland MM, Kulkarni V, et al. Preclinical evaluation of HIV-1 therapeutic ex vivo dendritic cell vaccines expressing consensus Gag antigens and conserved Gag epitopes. Vaccine. 2011;29:2110–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li F, Liu Y, Hong K, Meng X, Chen J, et al. HIV fragment gag vaccine induces broader T cell response in mice. Vaccine. 2011;29:2582–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Brockman MA, Schneidewind A, Lobritz M, Pereyra F, Rathod A, et al. HLA-B57/B*5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte [corrected] recognition. J Virol. 2009;83:2743–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02265-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga R, Lucchetti A, Galvan P, Sanchez S, Sanchez C, Hernandez A, et al. Relative dominance of Gag p24-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is associated with human immunodeficiency virus control. J Virol. 2006;80:3122–3125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3122-3125.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiepiela P, Ngumbela K, Thobakgale C, Ramduth D, Honeyborne I, Moodley E, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat Med. 2007;13:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland M, Heckerman D, Deng W, Rousseau CM, Coovadia H, Bishop K, et al. Broad and Gag-biased HIV-1 epitope repertoires are associated with lower viral loads. PloS One. 2008;3:e1424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julg B, Williams KL, Reddy S, Bishop K, Qi Y, Carrington M, et al. Enhanced anti-HIV functional activity associated with Gag-specific CD8 T-cell responses. J Virol. 2010;84:5540–5549. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Qiu C, Liu LX, Feng YM, Zhu T, Xu JQ. A mouse model based on replication-competent Tiantan vaccinia expressing luciferase/HIV-1 Gag fusion protein for the evaluation of protective efficacy of HIV vaccine. Chin Med J. 2009;122:1655–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H, Ishida Y, Tsubata T, Yagita H, et al. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:765–772. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinselmeyer BH, Heydari S, Sacristan C, Nayak D, Cammer M, Herz J, et al. PD-1 promotes immune exhaustion by inducing antiviral T cell motility paralysis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:757–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikuma S, Terawaki S, Hayashi T, Nabeshima R, Yoshida T, Shibayama S, et al. PD-1-mediated suppression of IL-2 production induces CD8+ T cell anergy in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:6682–6689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Wan N, Zhang S, Moore Y, Wan F, Dai Z. Cutting edge: programmed death-1 defines CD8+CD122+ T cells as regulatory versus memory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:803–807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavioli R, Cellini S, Castaldello A, Voltan R, Gallerani E, Gagliardoni F, et al. The Tat protein broadens T cell responses directed to the HIV-1 antigens Gag and Env: implications for the design of new vaccination strategies against AIDS. Vaccine. 2008;26:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrantelli F, Maggiorella MT, Schiavoni I, Sernicola L, Olivieri E, Farcomeni S, et al. A combination HIV vaccine based on Tat and Env proteins was immunogenic and protected macaques from mucosal SHIV challenge in a pilot study. Vaccine. 2011;29:2918–2932. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]