Abstract

Background

Extended spectrum betalactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms are a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) have been recovered from the hospital environment. These drug-resistant organisms have also been found to be present in humans as commensals. The present investigation intended to isolate ESBL-producing E. coli from the gut of already infected patients; to date, only a few studies have shown evidence of the gut microflora as a major source of infection.

Aims

This study aimed to detect the presence of ESBL genes in E.coli that are isolated from the gut of patients who have already been infected with the same organism.

Methods

A total of 70 non-repetitive faecal samples were collected from in-patients of our hospital. These in-patients were clinically diagnosed and were culture-positive for ESBL-producing E. coli either from blood, urine, or pus. Standard microbiological methods were used to detect ESBL from clinical and gut isolates. Genes coding for major betalactamase enzymes such as bla CTX-M , bla TEM, and bla SHV were investigated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Results

ESBL-producing E. coli was isolated from 15 (21 per cent) faecal samples of the 70 samples that were cultured. PCR revealed that out of these 15 isolates, the bla CTX-M gene was found in 13 (86.6 per cent) isolates, the bla TEM was present in 11 (73.3 per cent) isolates, and bla SHV only in eight (53.3 per cent) isolates. All 15 clinical and gut isolates had similar phenotypic characters and eight of the 15 patients had similar pattern of genes (bla TEM, bla CTX-M, and bla SHV) in their clinical and gut isolates.

Conclusion

Strains with multiple betalactamase genes that colonise the gut of hospitalised patients are a potential threat and it may be a potential source of infection.

Keywords: Stool, colonisation, ESBL E.coli

What this study adds:

-

What is known about this subject?

Drug-resistant organisms such as the ESBL-producing E.coli colonise the gut of healthy individuals and hospitalised patients. The rate of colonisation ranges from 7.4–17 per cent.

-

What new information is offered in this study?

Patients with an existing E.coli infection were found to be colonised with ESBL-producing E.coli in their gut as an endogenous microflora.

-

What are the implications for research, policy, or practice?

More specific typing methods would validate the genetic similarity of strains; however, as the endogenous microflora (gut) could be a source of infection, strict hygiene and infection control practices are therefore warranted.

Background

Extended spectrum betalactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms are a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. The ESBLs are betalactamases, which confer bacterial resistance to penicillin, the first-, second-, and third- generation cephalosporins, and aztreonam (but not the cephamycins and carbapenem) by hydrolysis of these antibiotics.1 These organisms are inhibited by betalactamase inhibitors like clavulanic acid and tazobactam.

Since its detection in 1983, various organisms have been known to produce these hydrolysing enzymes worldwide among which E.coli is the most common ESBL-producing organism.1,2 They are known to cause outbreaks of life-threatening infections in hospitalised patients.2 The common risk factors for acquiring infection with ESBL-producing organisms are exposure to prolonged antibiotic therapy, invasive procedures, intra-abdominal surgery, and prolonged hospital stay.3,4 The patient’s own microflora is thought to be a major contributing factor in advancing the infection.5 Faecal colonisation of ESBL-producing organisms among healthy individuals in the community is reported to be around 5.5–8 per cent, while colonisation among hospitalised patients was found to be higher; i.e., around 15 per cent.5 However, colonisation studies on patients who have already been infected with an ESBL-producing strain are limited. The present study was undertaken to detect the presence of some common betalactamase genes in E.coli that are isolated from the gut of patients who had recently been infected with the same organism.

Method

A prospective one-year study was conducted during 2010 in a tertiary care hospital. Non-repetitive faecal samples were collected from 70 in-patients who had laboratory-confirmed infection with an ESBL-producing E.coli cultured from their blood, urine, or pus. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Committee and an informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Definitions

The following definitions are used:

Clinical isolate: An isolate from an active site of infection confirmed by culture.

Gut isolate: An isolate from the faeces of a patient who has an active infection with ESBL-producing E. coli and who does not have diarrhoea/dysentery.

In brief, stool culture was performed with a loopful of the faeces sample inoculated onto a MacConkey agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) incorporated with ceftazidime [MacConkey agar was prepared by the addition of ceftazidime (2μg/ml) to the cooled agar before pouring].6 After overnight incubation at 37°C, 5–6 lactose-fermenting colonies were picked up for further processing. All the gut and clinical isolates were tested for their antibiotic susceptibility pattern according to the CLSI guidelines (CLSI, 2010).7 All the isolates were also screened for ESBL production (a zone size of ≤27mm for cefotaxime and ceftazidime ≤22mm were considered positive for ESBL production). Isolates were further confirmed as ESBL producers by the double disk diffusion method (CLSI 2010).7 Ceftazidime (30μg) disk with and without clavulanic acid (30μg/10μg) were used. A ≥5mm increase in the zone diameter for ceftazidime with clavulanic acid was considered positive for ESBL.7 Reference strains such as Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 were used as a negative and positive control, respectively.

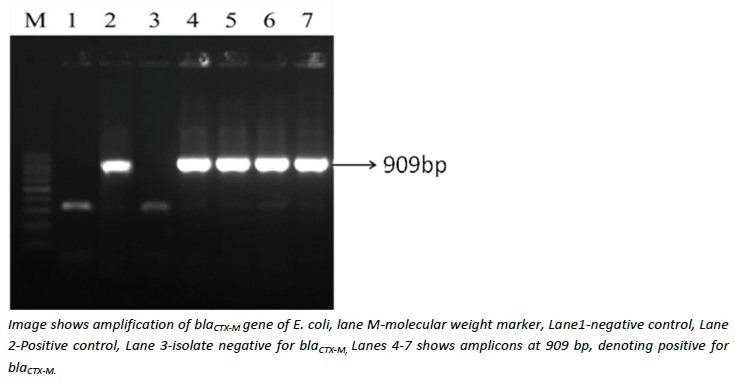

PCR was performed on all the 15 clinical and gut isolates to detect bla CTX-M, bla TEM, and bla SHV genes using specific primers and PCR conditions as described earlier.8 Primer sequences and their product sizes are given in Table 1.8 PCR reactions were carried out individually for detection of each of the genes. Briefly, the amplification was carried out in an Eppendorf thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with the following conditions: (1) Initial denaturation step for five minutes at 94°C; (2) 35 cycles of PCR were carried out with each cycle consisting of one minute at 94°C, 1 min at 54°C, and two minutes at 72°C; and (3) a final extension step was performed for five minutes at 72°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on one per cent agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and the bands were visualised under UV illumination (Bio-Rad, USA) (Figure 1).

Table 1: Details of primers used in this study and their amplicon sizes8.

| Target gene | Primer name | Primer sequence | Amplicon size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bla TEM | TEM-F | TCCGCTCATGAGACAATAACC | 931 | 8 |

| TEM-R | TTGGTCTGACAGTTACCAATGC | |||

| bla SHV | SHV-F | TGGTTATGCGTTATATTCGCC | 868 | 8 |

| SHV-R | GGTTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCT | |||

| bla CTX-M | CTX-F | TCTTCCAGAATAAGGAATCCC | 909 | 8 |

| CTX-R | CCGTTTCCGCTATTACAAAC |

Figure 1: Gel electrophoresis showing PCR amplification of blaCTX-M gene.

The comparative study of risk factors among colonisers and non-colonisers were statistically tested using Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Results

Out of the 70 stool samples tested, 15 (21 per cent) patients were found to be colonised with ESBL-producing E.coli in their gut. Out of the 15 colonised patients most (93 per cent) of them were adults and less than half (six patients) were admitted to the intensive care unit during the course of their hospital stay. Of these, 11 had urinary tract infection with an ESBL-producing E.coli, while two patients had blood stream infections, and two others had suppurative infections. In four patients, infection followed surgical procedures like hernioplasty, sigmoid colostomy, k-wiring, and abdominal hysterectomy. Central venous catheters were inserted in four patients, while 10 had urinary catheters.

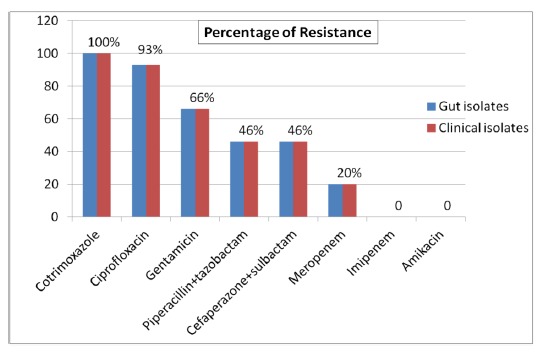

All ESBL-producing E.coli isolated from the gut microflora and the clinical isolates were sensitive to imipenem and amikacin, while gentamicin resistance was seen in 10 (66 per cent), ciprofloxacin in 14 (93 per cent), and meropenem in three (20 per cent) of the isolates. Resistance to betalactam with betalactamase inhibitor combination (cefaperazone + sulbactam and piperacillin + tazobactam) was noted in seven (46 per cent) isolates (Figure 2). The antibiogram profiles of the faecal and clinical isolates were identical for each patient (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Antimicrobial resistance profiles of 15 gut isolates in comparison to the clinical isolates.

Detection of betalactamase genes among gut and clinical isolates

Out of the 15 gut and clinical isolates, the bla CTX-M was found in 13 (86.6 per cent) isolates, and the bla TEM was present in 11 (73.3 per cent) isolates. The bla SHV types were present in eight (53.3 per cent) isolates. Two or more genes were present in 12 (80 per cent) of the stool isolates, the commonest combination was the presence of all three genes (bla TEM, bla CTX-M, and bla SHV types), which was present in six (40 per cent) gut isolates, followed by combination of bla TEM> + bla CTX-M in four (26.6 percent), and bla SHV + bla CTX-M < inline-formula/ one (6.6 per cent) isolate. Only two of the isolates had a single gene, one had bla CTX-M and the other had bla TEM (Table 2).

Table 2:Presence of different betalactamase genes in E.coli isolated from clinical and gut isolates of colonised patients.

| Genes | Clinical isolate n=15 (%) |

Gut isolate n=15 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| bla CTX-M | 13 (86.6) | 13 (86.6) |

| bla TEM | 11 (73.3) | 11 (73.3) |

| bla SHV | 8 (53.3) | 8 (53.3) |

| bla CTX-M + bla TEM+ bla SHV | 5 (33.3) | 6 (40) |

| bla CTX-M + bla TEM | 4 (26.6) | 4 (26.6) |

| bla CTX-M + bla SHV | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.6) |

The presence of bla CTX-M, bla TEM, and bla SHV genes in the gut isolates were of similar pattern as in clinical isolates in eight patients whose guts were colonised with ESBL strains (Table 3).

Table 3:Similarity in the presence of betalactamase genes between clinical and gut isolates.

| Patient ID | Clinical isolate | Gut isolate | Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | bla CTX-M, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | - |

| S2 | bla CTX-M | bla TEM, bla SHV | - |

| S3 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | bla CTX-M | - |

| S4 | bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | - |

| S7 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | + |

| S10 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | + |

| S14 | bla CTX-M | bla CTX-M | + |

| S18 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | + |

| S27 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | + |

| S34 | bla TEM | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | - |

| S38 | bla CTX-M, bla SHV | bla TEM | - |

| S45 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | bla CTX-M, bla SHV | - |

| S49 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | + |

| S59 | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV | + |

| S64 | bla CTX-M , bla TEM | bla CTX-M, bla TEM | + |

Discussion

ESBL-producing organisms are presently one of the major causes of hospital-acquired infections.9 Worldwide, the prevalence of ESBL production among E.coli isolates in a hospital setting was highest in Latin America (13.5 per cent), followed by Asia/Pacific Rim (12per cent), Europe (7.6 per cent), and North America (2.2 per cent).10 The prevalence of ESBL-producing gram-negative isolates in India is alarmingly high (19–69 per cent).11–13 In various studies conducted across India the prevalence rate of ESBL-producing E.coli was found to be 41–62 per cent.14–16

There is general consensus that gut colonisation in patients by these bacteria is an important reservoir and source of infection.17 Valverde et al. had reported that the rate of faecal carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae had increased significantly in hospitalised and outpatients from 0.3 and 0.7 per cent, respectively, in 1991, to 11.8 and 5.5 per cent, respectively, in 2003.18 Faecal carriage rates of ESBL-producing E.coli among children and women attending antenatal clinics in India was found to be 9 per cent and 15 per cent, respectively.19,20 There are several reports on the prevalence of faecal carriage of ESBL-producing organisms in both inpatients and outpatients ranging from 5.5–17 percent.21–23 Interestingly, the present study witnessed a higher percentage of colonisation (21 per cent) and this could be due to an already existing infection with an ESBL-producing E.coli. All the previous studies on gut microflora were done on either inpatients or outpatients randomly without evidence of an infection.18–24

Several studies have already revealed various risk factors associated with colonisation and infection with ESBL-producing organisms. Prolonged hospital stay, patients on medical devices like urinary catheters, central venous lines, etc., have been associated with infections by these organisms.25,26 Further, surgical procedures and indiscriminate use of antibiotics are added risk factors for the acquisition of ESBL-producing organisms.27–30 In this study a major risk factor for colonisation with ESBL producers appears to be invasive devices like urinary catheterisation (p value=0.04). The majority of the colonised patients (73 per cent) in the present study had urinary tract infection with ESBL-producing E. coli, which probably explains the association (Table 4). Although all the colonisers (100 per cent) were on antibiotic therapy, it did not appear to be a significant risk factor statistically since the number of colonisers were minimal (15 patients), however, antibiotic usage may act as a risk factor, as the antibiotic pressure is high in healthcare facilities.

Table 4:Comparative study of risk factors among colonisers and non-colonisers.

| Characteristics | Colonisers n=15 (%) |

Non-Colonisers n=55 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.21 | ||

| –Male | 9 (60%) | 23 (42%) | |

| –Female | 6 (40%) | 32 (58%) | |

| ICU Admission | 6 (40%) | 9 (16%) | 0.07* |

| Urinary catheter | 10 (67%) | 20 (36%) | 0.04 |

| Antibiotic usage | |||

| –Betalactams | 9 (60%) | 32 (58%) | 0.90 |

| –Fluoroquinolones | 7 (47%) | 21 (38%) | 0.55 |

| Surgical procedure | 4 (27%) | 9 (16%) | 0.45* |

Fisher’s Exact Test

With a limited choice of antibiotics, ESBL-producing isolates are reported to be susceptible to imipenem and meropenem, but resistant to a panel of antibiotics, including gentamicin, amikacin, and ciprofloxacin.31–33 Resistance pattern of E.coli isolated from the gut microflora in the present study is quite alarming as 46 per cent of isolates were resistant to the betalactamase inhibitors (cefaperazone + sulbactam) and (piperacillin + tazobactam). As normal microflora of the gut, these organisms could be a threat to the patients who have been colonised, and to the patients who are in the vicinity. This could also pose a challenge to hospital infection control practices.

The antibiogram of the gut isolates had identical susceptibility patterns in comparison to the clinical isolates of the same patient, even though antibiogram typing is a crude method it reiterates an association. However, prior isolation from the gut and a follow-up to see if these patients developed infection subsequently could be a better analytical tool. Molecular typing using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) or pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to determine the clonal relatedness of the isolates could have been a better tool to validate such observation. Not performing any of these methods is a limitation of our study.

Earlier studies on genotypic detection of ESBL-producing E. coli from the gut have shown CTX-M as the most common type with 75 per cent of the isolates followed by SHV (20 per cent).33,34 In the present study, CTX-M was found in 86 per cent (n=13), the TEM variety in 73 per cent (n=11) of gut isolates. The SHV type was present in only 53.3 per cent (n=8) of isolates. Sequencing of the bla TEM, and bla SHV genes were not performed to confirm it as ESBL genes. However, the presence bla CTX-M gene and the confirmation of all the isolates by phenotypic methods (disk diffusion) deem them as ESBL strains. The presence of one or more resistant genes in a normal coliform suggests that these strains could be a potential threat for causing a future infection elsewhere in the body.

Conclusion

Acquisition with an ESBL-producing organism might be due to dissemination of these resistant strains in the hospital environment, leading to transmission from a common source and/or person-to-person transmission.35 Our data suggest that colonisation with ESBL-producing organisms could be due to an active infection with an ESBL-producing E. coli. However, specific typing methods are required to support this evidence. The endogenous microflora of colonised patients could act as a reservoir for a future infection with a drug-resistant organism. Therefore, it is prudent to suggest that as a routine, patients admitted to critical care areas such as ICUs, may be screened for colonisation with ESBL-producing organisms. Strict adherence to patient hygiene and infection control practices may be enforced to curtail hospital-acquired infections. Rationalising antibiotic therapy would substantially decrease pressure on the gut microflora and thereby limit acquisition of resistance genes among these organisms.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

PIMS Ethical Review Committee Ref: PIMS/Ethics/2008-15

Please cite this paper as: Asir J, Nair S, Devi S, Prashanth K, Saranathan R, Kanungo R. Simultaneous gut colonisation and infection by ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in hospitalised patients. AMJ 2015;8(6):200–207 http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2015.2358

References

- 1.Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended spectrum betalactamases: A clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford PA. Extended spectrum betalactamases in the 21st century: Characterization, epidemiology and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:933–51. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.933-951.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osthoff M, Mcguinness SL, Wagen AZ. et al. Urinary tract infections due to extended-spectrum beta lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria: identification of risk factors and outcome predictors in an Australian tertiary-referral hospital. Int J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.03.006. 2015 Mar 10. pii: S1201-9712(15)00067-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhary U, Aggarwal R. Extended spectrum betalactamases-An emerging threat to clinical therapeutics. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Ami R, Schwaber MJ, Navon-Venezia S. et al. Influx of extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae into the hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:925–34. doi: 10.1086/500936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris AD, McGregor JC, Johnson JA. et al. Risk factors for colonization with ESBL producing bacteria and ICU admission. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1144–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1308.070071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twentieth Informational Supplement M100-S20. CLSI, Wayne, PA, USA, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiratisin P, Apinsarthanarak A, Laespira C. et al. Molecular Characterization and Epidemiology of Extended-Spectrum betalactamase Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Causing Health Care-Associated Infection in Thailand, Where the CTX-M Family is Endemic . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2818–24. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00171-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidler JA, Battegay M, Tschudin-Sutter S. et al. Enterococci, Clostridium difficile and EBSL-producing bacteria: epidemiology, clinical impact and prevention in ICU patients. Swiss Med Wkly. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.14009. 2014 Sep 24;144:w14009. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.14009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing organisms. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:345–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathak A, Marothi Y, Kekre V. et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing pathogens: results of a surveillance study in two hospitals in Ujjain, India. Infect Drug Resist. 2012;5:65–73. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S30043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhattacharya S. Is screening patients for antibiotic-resistant bacteria justified in the Indian context? Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:213–7. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.83902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur N, Sharma S, Malhotra S. et al. Urinary tract infection: aetiology and antimicrobial resistance pattern in infants from a tertiary care hospital in northern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:DC01–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8772.4919. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/8772.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babypadmini S, Appalaraju B. Extended spectrum–lactamases in urinary isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia–prevalence and susceptibility pattern in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:172–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umadevi S, Kandhakumari G, Joseph NM. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of ESBL producing gram negative bacilli. J Clin Diag Res. 2011;5:236–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhal S, Mathur T, Khan S. et al. Evaluation of methods for AmpC beta-lactamase in gram-negative clinical isolates from tertiary care hospitals. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23:120–4. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.16053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kammili N, Cherukuri N, Palvai S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary care hospital . Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32:205–7. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.129856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valverde A, Coque TM, Sanchez-Monreno MP. et al. Dramatic increase in prevalence of fecal carriage of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae during non outbreak situations in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4769–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4769-4775.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shakya P, Barrett P, Diwan V. et al. Antibiotic resistance among Escherichia coli isolates from stool samples of children aged 3 to 14 years from Ujjain, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:477. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-477. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pathak A, Chandran SP, Mahadik K. et al. Frequency and factors associated with carriage of multi-drug resistant commensal Escherichia coli among women attending antenatal clinics in Central India. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:199–208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jesus RB, Lorena LC, Maria DN. et al. Faecal carriage of extended spectrum betalactamase-producing Escherichia coli: Prevalence, risk factors and molecular epidemiology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1142–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villar HE, Baserni MN, Jugo MB. Faecal carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in community settings. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(8):630–4. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kader AA, Kumar A, Kamath KA. Fecal carriage of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients and symptomatic healthy individuals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1114–6. doi: 10.1086/519865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janvier F, Delacour H, Tesse S. et al. Faecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enterobacteria among soldiers at admission in a French military hospital after aeromedical evacuation from overseas. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;10:1719–23. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lautenbach E, Patel JB, Bilker WB. et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: risk factors for infection and impact of resistance on outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1162–71. doi: 10.1086/319757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neulier C, Birgand G, Ruppe E. et al. Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: risk factors for ESBLPE. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spadafino JT, Cohen B, Liu J. et al. Temporal trends and risk factors for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in adults with catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:39. doi: 10.1186/s13756-014-0039-y. doi:10.1186/s13756-014-0039-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayakawa K, Gattu S, Marchaim D. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Isolation of Escherichia coli Producing CTX-M-Type Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase in a Large U.S. Medical Center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8):4010–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02516-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bert F, Larroque B, Dondero F. et al. Risk factors associated with preoperative fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in liver [transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:84–9. doi: 10.1111/tid.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Bano J, Navarro MD. et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in Nonhospitalized Patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1089–94. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1089-1094.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar D, Singh AK, Ali MR. et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of Extended Spectrum β- Lactamase (ESBL) Producing Escherichia coli from Various Clinical Samples. Infect Dis (Auckl) 2014;7:1–8. doi: 10.4137/IDRT.S13820. doi: 10.4137/IDRT.S13820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husam SK, Khalid M, Bindayna. et al. Extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: trends in the hospital and community settings. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:295–9. doi: 10.3855/jidc.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerma M, Cebrian L, Gimenez M. et al. Beta-lactam susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infections exhibiting different resistance phenotypes. J Rev Esp Quimioter. 2008;21:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miro E, Mirelis B, Navarro F. et al. Surveillance of extended spectrum beta-lactamases from clinical and fecal carriers in Barcelona, Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:1152–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulzii O, Luvsansharav UO, Hirai I. et al. Fecal carriage of CTX-M beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in nursing homes in the Kinki region of Japan. Infect Drug Resist. 2013;6:67–70. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S43868. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S43868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]