Abstract

The recent publication of fetal growth and gestational age–specific growth standards by the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century Project and the previous publication by the WHO of infant and young child growth standards based on the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study enable evaluations of growth from ∼9 wk gestation to 5 y. The most important features of these projects are the prescriptive approach used for subject selection and the rigorous testing of the assertion that growth is very similar among geographically and ethnically diverse nonisolated populations when health, nutrition, and other care needs are met and the environment imposes minimal constraints on growth. Both studies documented that with adequate controls, the principal source of variability in growth during gestation and early childhood resides among individuals. Study sites contributed much less to observed variability. The agreement between anthropometric measurements common to both studies also is noteworthy. Jointly, these studies provide for the first time, to my knowledge, a conceptually consistent basis for worldwide and localized assessments and comparisons of growth performance in early life. This is an important contribution to improving the health care of children across key periods of growth and development, especially given the appropriate interest in pursuing “optimal” health in the “first 1000 d,” i.e., the period covering fertilization/implantation, gestation, and postnatal life to 2 y of age.

Keywords: fetal growth, infant growth, child growth, growth assessment, nutritional assessment, growth standards, growth monitoring

Introduction

The recent publication of fetal growth and gestational age–specific birth weight, length, and head circumference standards by the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st)3 Project and the previous publication by the WHO of infant and young child growth standards (the WHO Child Growth Standards) based on the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) enable growth monitoring from early pregnancy (∼9 wk) through 5 y of age (1–6). Similarities between the 2 studies’ prescriptive approaches, designs, and international sampling frames provide for the first time, to my knowledge, a conceptually consistent basis for worldwide and localized assessments and comparisons of growth performance in early life. These are important contributions to improve health care by harmonizing common criteria used in health screening, growth monitoring, and assessing the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve health across key periods of growth and development.

Two ongoing dynamics make the new standards particularly relevant to contemporary health policies and practices. These relate to a steadily improving understanding of the significance of health in preceding life stages to subsequent well-being and the growing robustness of assertions that health is a prerequisite for economic development, not just an important benefit that accompanies its attainment. The former has brought steadily greater interest in pursuing “optimal” health in the “first 1000 d,” i.e., the period covering fertilization/implantation and gestation through the postnatal age of 2 y (7). The second brings increasing urgency to the view that investments of human and financial resources to improve health yield substantial short- and long-term returns, rather than only costs unlikely to result in broad, realized gains (8, 9). Nonetheless, some correctly caution against uncritically linking anthropometric data to living standards (10).

The 2 most important features of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS are, first, that both were based on a prescriptive approach that broadened the definition of health beyond an-absence-of-disease criterion to include the adoption of recommended health practices and behaviors, parental education, and socioeconomic and environmental factors of significance to short- and long-term health (11, 12) and, second, that both rigorously tested the assertion that growth is very similar among geographically and ethnically diverse nonisolated populations when health, nutrition, and other care needs are met, and the environment imposes minimal constraints on growth. In effect, rather than describe how children grew at particular times and places, the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS collected data describing how fetuses/children should grow regardless of time and place, supporting a healthy start for all children. This article provides a brief summary of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS, identifies examples of policies supported by the results of both studies, and suggests selected research opportunities that arise from the findings of the 2 studies.

Design and Methods

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project included 3 studies conducted at 8 sites: Brazil, China, India, Italy, Kenya, Oman, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These studies included 1) a cross-sectional component (n = 59,137 women of whom 20,486 gave birth to eligible newborns) designed for the purpose of constructing newborn standards; 2) a longitudinal fetal growth component conducted in a cohort of healthy women (n = 4607) in whom fetal growth was monitored with ultrasound scans every 4–6 wk from 9 to 14 wk of gestation to birth and their progeny were followed to age 2 y to assess health, growth, and neurodevelopment; and 3) a postnatal longitudinal growth component that closely monitored infants in the longitudinal cohort who were born prematurely. In total, nearly 60,000 women, children, and their families participated in the project’s 3 components (13).

The MGRS obtained data on growth trajectories from birth to 5 y in children enrolled from 6 sites in Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States (14). It included 2 components, a longitudinal one (n = 1743) from 0 to 24 mo (that included 21 home visits) and a cross-sectional (n = 6697) one that included children aged 18–71 mo (15). In applying a prescriptive approach, both studies operationalized definitions for “optimal” nutrition, environments, and care with the goal of defining “optimal” growth, within the constraints of studies conducted in community-based settings.

Similarities between the 2 studies extended beyond a common prescriptive approach and their international reach. Other similarities were their community-based designs that avoided biases such as those likely to emerge from hospital-based sampling frames and extensive, real-time quality controls that contributed importantly to the high quality of their data. Those controls included the provision of uniform equipment across sites, strict standardization including training of research staff and multiple-blinded observer protocols for all key measurements, and regularly scheduled assessments of adherence to standardized procedures, regular testing of the standardized equipment’s functionality, and real-time monitoring of collected data for accuracy, precision, and integrity. These were described in detail in previous publications (13, 16).

Individual and site eligibility criteria used by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS were similar. Criteria in both studies were selected with the goal of identifying healthy populations seemingly free of disease, following current health recommendations, and living in environments unlikely to constrain growth. The specific contexts of healthy conditions, however, necessarily differed among study sites because individuals from very diverse countries were enrolled, e.g., India, Italy, Kenya, and Norway, but all contexts shared at least one common feature, i.e., each was assessed to be nongrowth constraining. Environmental criteria were of special concern to the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. The absence or sufficiently low levels of nonmicrobiological environmental contaminants that could adversely affect maternal and fetal health was documented for each candidate site, e.g., domestic smoke, unacceptable exposures to pollution, and/or radiation (17).

Some site, environmental, and population characteristics were controlled across all sites, e.g., altitude because of its documented impact on fetal and postnatal growth (18, 19). The INTERGROWTH-21st Project set its altitude limit at 1600 m in order to include a sub-Saharan malaria-free region (the Parkland area in Nairobi, Kenya); similarly, the MGRS limited its study populations to those living at <1500 m. The longitudinal aspects of both studies required low mobility populations. Site eligibility in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project was limited to urban communities where at least 80% of prenatal care and deliveries occurred within a manageable number of institutions. A similar criterion was used by the MGRS. The institutions, in turn, were judged to have the human and physical resources necessary to meet the 2 studies’ requirements. For individuals enrolled in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project, eligibility was restricted to those with no obstetric and/or gynecologic or other health histories and conditions likely to affect pregnancy adversely, those who initiated antenatal care before 14 wk gestation, and those who met other criteria consistent with good nutrition, health, and socioeconomic circumstances. Additionally, only singleton pregnancies achieved through natural conception were eligible. Detailed site and individual eligibility criteria have been published previously (13, 14, 20–25).

For the MGRS, in addition to the documentation of normal pregnancies, feeding criteria were particularly relevant in that enrollment was limited to women willing to try breastfeeding exclusively or predominantly for 4–6 mo with continued breastfeeding for at least 1 year. Nearly 75% of infants were exclusively or predominantly breastfed for at least 4 mo, 99.5% were started on complementary foods by 6 mo, and 68.3% were partially breastfed until at least 12 mo (26). Only children who were breastfed exclusively or predominantly for at least 4 mo with complementary feeding introduced by 6 mo and who continued breastfeeding for at least 1 y were included in the construction of the WHO standards. That success was due to, in large part, the selection of sites with existing breastfeeding support systems that the MGRS could strengthen (26). Other eligibility criteria were applied by the MGRS to avoid growth-constraining conditions. For example, only infants of women who did not smoke before or after delivery were included; as for the children, only singletons and those born at term and free of any noteworthy morbidity at birth were enrolled.

Results

Results published by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS are remarkably consistent notwithstanding the multiple year separation between the 2 studies’ data collection phases (1, 2, 6, 14, 27). Table 1 summarizes the standards that have been published by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS. The results that undergird those tools are of substantial importance to public health and clinical management. Of most interest are the 1) similarities in growth among geographically and ethnically diverse nonisolated populations enrolled by both studies notwithstanding intersite differences in parental anthropometry, 2) agreement between anthropometric measurements common to both studies at birth and 2 y, and 3) the high quality of the population-based, large data sets.

TABLE 1.

Anthropometric standards published by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS1

| Anthropometric measurement/index | Reference |

| Attained fetal growth (7–15 wk) | |

| CRL | Papageorghiou et al. (1) |

| Attained fetal growth (14 wk to birth) | |

| Head circumference for gestational age | Papageorghiou et al. (6) |

| Biparietal diameter for gestational age | Papageorghiou et al. (6) |

| Occipital parietal diameter for gestational age | Papageorghiou et al. (6) |

| Femur length for gestational age | Papageorghiou et al. (6) |

| Abdominal circumference for gestational age | Papageorghiou et al. (6) |

| Attained growth at birth | |

| Weight for gestational age at birth | Villar et al. (2) |

| Length for gestational age at birth | Villar et al. (2) |

| Head circumference for gestational age at birth | Villar et al. (2) |

| Attained postnatal growth | |

| Weight for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (3) |

| Length/height for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (3) |

| Weight-for-length/height | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (3) |

| BMI for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (3) |

| Midupper arm circumference for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (4) |

| Triceps skinfold for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (4) |

| Subscapular skinfold for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (4) |

| Head circumference for age | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (4) |

| Postnatal growth velocity | |

| Weight | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (5) |

| Length/height | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (5) |

| Head circumference | Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO (5) |

CRL, crown-rump length; INTERGROWTH-21st Project, International Fetal and newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century; MGRS, Multicentre Growth Reference Study.

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS applied 3 approaches jointly to assess the appropriateness of pooling growth data for the purpose of developing anthropometric standards: 1) estimating the relative contributions of intersite and interindividual variation to the total observed variation; 2) estimating differences between a site’s mean anthropometric measures and the corresponding “all-site” means relative to the corresponding “all site” SDs, i.e., “standardized size differences” (SSDs); and 3) sensitivity analyses that assessed the impact of deleting individual sites on the remaining data’s central tendencies (50th percentile) and values at the 3rd and 97th percentiles. For these purposes, both studies used measures of skeletal growth most likely to be normally distributed; i.e., crown-rump length (CRL; <14 wk gestation), fetal head circumference (FHC; 14–42 wk), and birth length (BL) were examined by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and length from birth to 2 y was used by the MGRS (1, 19–20). These were selected as the anthropometric characteristics least likely to be affected by recent trends related to overweight and obesity and, thus, the measures most reflective of inherent growth potentials.

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project found that 1.9%, 2.6%, and 3.5% of the total variability in CRL, FHC, and BL, respectively, were attributable to intersite differences. The contribution of interindividual differences in FHC to the total observed variation was 7-fold higher, i.e., ~19% of the total (27). Similar estimations were not made for CRL and BL because they were only measured cross-sectionally. The proportion of total variability in length attributable to intersite differences in the MGRS was 3.4%, a value similar to those reported by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. The proportion of total variability attributable to interindividual differences in the MGRS was 70%, or ~20 times the contribution of intersite differences (28). These findings are consistent with growth/stature being a complex quantitative genetic trait (29–31).

Both studies applied a cutoff of ≤0.5 for estimates of SSDs to pool data. This was considered a conservative cutoff because it is based on SDs derived from means of 3 highly standardized measures of the same subject at each study visit. That protocol resulted in relatively small SDs unlikely to be achieved in less-controlled settings/protocols. The low SDs, in turn, increased SSD estimates. One hundred twenty-eight SSDs were calculated for specified gestational age windows by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project in its examination of intersite heterogeneity/homogeneity. Only 1 of the 128 values was >0.5, i.e., 0.58. The MGRS made 54 analogous estimates for age-specific comparisons of length (birth to 2 y) and stature (2–5 y). None exceeded 0.5.

The results of sensitivity analyses were similarly consistent between the 2 studies. Impacts on the overall 3rd, 50th, and 97th percentile values after sequentially eliminating any one individual site’s values were minimal in both the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and the MGRS. The results of these 3 approaches for assessing the heterogeneity/homogeneity of the sites’ growth characteristics strongly support the universality of growth characteristics of nonisolated populations whose living conditions do not constrain growth.

The agreement between anthropometric measurements common to both studies also is noteworthy. Mean BL for the longitudinal and cross-sectional components of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project were strikingly similar, 49.4 ± 1.9 cm (mean ± SD) and 49.5 ± 1.9 cm, respectively, confirming the representativeness of the longitudinal sample, and even more striking was their similarity to that of the MGRS’ corresponding value, 49.5 ± 1.9 cm. The birth weights for the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS also were strikingly similar, 3.3 ± 0.4 kg and 3.3 ± 0.5 kg for the former’s longitudinal and cross-sectional components, respectively, and 3.3 ± 0.5 kg for the MGRS. Length and head circumference measurements for boys and girls at 1 y of age in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project corresponded to the MGRS’ 49th and 52nd percentiles and 49th and 50th percentiles, respectively.

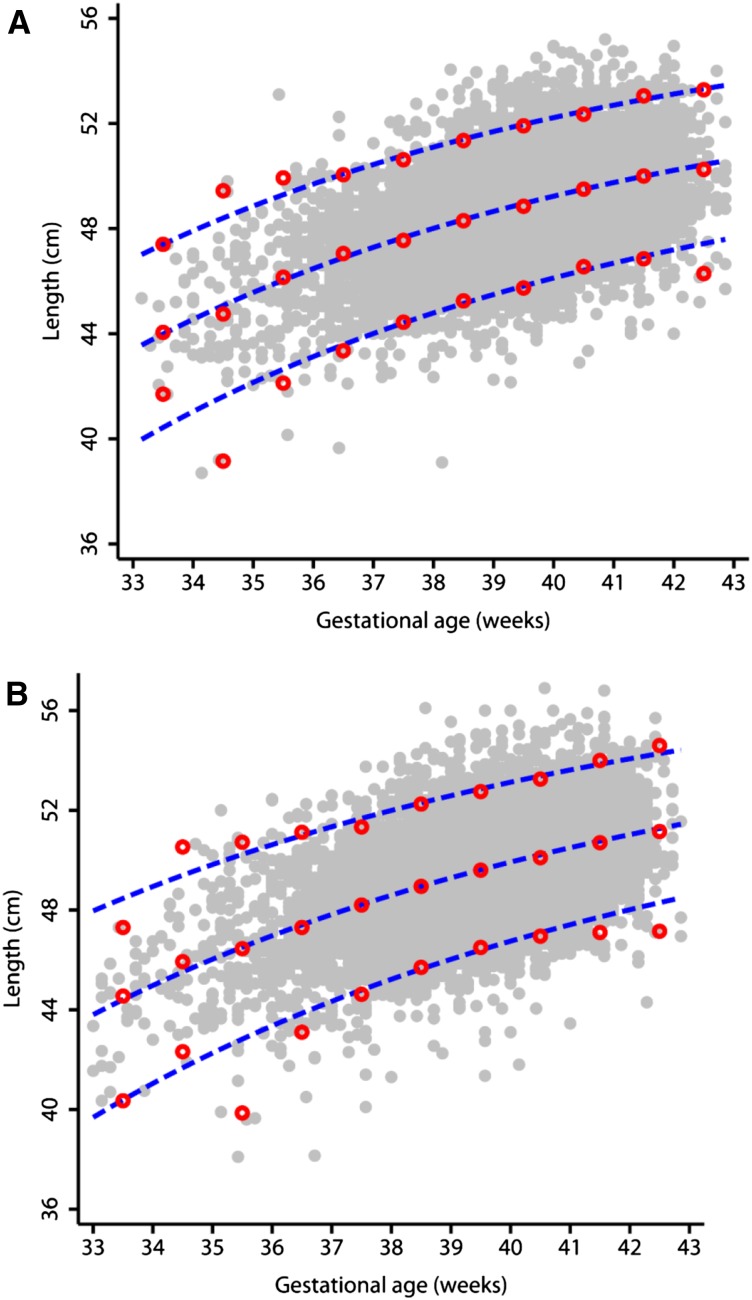

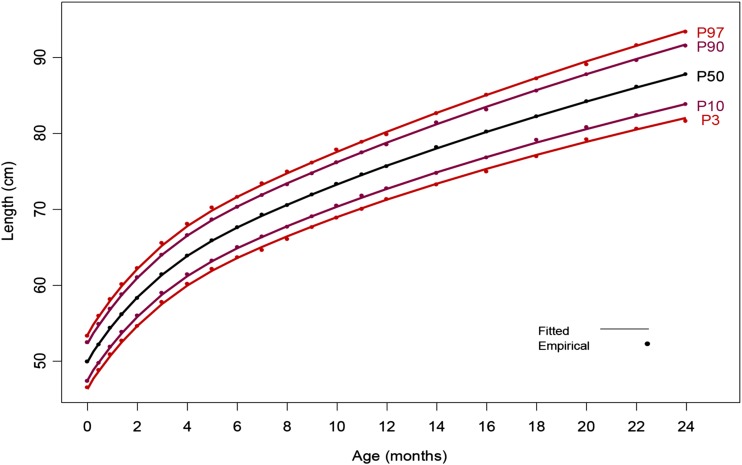

Examples of the resulting MGRS and INTERGROWTH-21st Project anthropometric data are found in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 illustrates smoothed curves for BL of infant girls and boys born at 33–43 wk gestation, respectively, and overlapping empirical values in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Figure 2 illustrates smoothed curves for the 3rd, 50th, and 97th percentiles for length from birth to 2 y of age with overlapping empirical values in the MGRS.

FIGURE 1.

Fitted 3rd, 50th, and 97th smoothed percentile curves (dashed blue lines) for BL according to gestational age showing empirical values for each week of gestation (open red circles) and the actual observations (closed gray circles). (A) Girls; (B) boys. BL, birth length. Reproduced from reference 2 with permission.

FIGURE 2.

Mean length from birth through 2 y illustrated as smoothed percentile curves and corresponding empirical observations. P3, 3rd percentile; P10, 10th percentile; P50, 50th percentile; P90, 90th percentile; P97, 97th percentile. Reproduced from reference 3 with permission.

Discussion

Results of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS, including similarities among study sites and agreement between the 2 studies, underscore the universality of the potential of physical growth from early gestation to at least 5 y of age in nonisolated, healthy human populations. Those findings were not unexpected given earlier work published by Habicht et al. (32) and others (33, 34). They also are consistent with knowledge regarding the genetic control of stature, the genetic underpinnings of complex quantitative traits, and anthropologic investigations of human migrations (29–31).

Beyond the findings’ conceptual importance, results from both studies provide a common international norm for early growth that is most consistent with a healthy start for all children and provide tools for applying those norms to both populations and individuals. Continuity of antenatal and postnatal care, using the same conceptual instruments from <9 wk of pregnancy (including pregnancy dating) to the neonatal period and beyond, harmonized across countries is a major step forward to improve quality of care in maternal and child health. The ease of use, relevance, and need for such tools was affirmed by the rapid global adoption of the WHO international growth standards (based on the findings of the MGRS) by >125 countries within 6 y of their release (35). A similar global acceptance and wide implementation are expected for the standards resulting from the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.

Affirming the universality of human physical growth potential and the availability of its operational counterpart, the first international “prescriptive” growth standards are particularly timely. Cumulative evidence supports that well-being in preceding life stages is key to maximizing health in subsequent periods and that early life stages have the most profound effect of all on health. This increasing awareness has led to a steadily growing interest in optimizing health in the first 1000 d (7, 36, 37). Arguably, the most evocative illustration of this perspective is the hypothesis proposed by Barker (36) ~20 y ago. The “early origins of adult disease” hypothesis is countered often by arguments that point to “continuity of circumstances” as alternative explanations for lifelong and transgenerational impacts of early life stages on adult chronic diseases (38, 39). On the other hand, animal studies have countered such arguments and explored mechanisms responsible for links between early health and adult disease and transgenerational effects of early life experiences (40, 41).

The 2 international sets of growth standards are appropriate for use in populations and individuals. That wide range of applications to health care is enabled by 2 key characteristics of growth. The first applies to growth generally and the second is a consequence of the high velocity of growth in early life stages. First, “much must go right” for growth to proceed normally at individual and population levels. This characteristic is particularly useful for screening purposes because growth is sensitive to a wide range of influences but is seldom diagnostic. Second, the high velocity of early growth enables relatively rapid evaluations of interventions and/or changing conditions (42).

In an extensive study that led to the MGRS and INTERGROWTH-21st Project, the WHO reviewed the “significance of anthropometric indicators and indices…(provided) guidance on the use and interpretation of anthropometric measures (in various life stages)…(and outlined) specific applications of anthropometry in individuals and populations for purposes of screening for targeting and evaluating interventions” (42). Importantly, the MGRS's and INTERGROWTH-21st Project’s community-based sampling frames, the inclusion of communities from diverse global regions, and the common prescriptive approach based on social and environmental conditions, in addition to an absence-of-disease criterion, also provide realistic targets for normalizing growth locally and globally.

There also are other pragmatic considerations that merit attention. The selection of references or standards matters to decision-making. Conflicting inferences derived from the application of the previous international growth reference for young children, the CDC 2000, the current WHO standards for infants and young children, and various fetal biometry references have been examined recently. These investigations illustrated disparate conclusions that resulted from their application to the same data, e.g., in assessments of breastfeeding adequacy (43), determination of rates of stunting (43, 44), rates of biparietal diameters below the fifth percentile (45), diagnosis of excess weight gain (43, 46), and assessments of mortality risk (47).

It is too early to assess whether standards derived from the INTERGROWTH-21st Project will be adopted as widely as those derived from the MGRS; the WHO standards have undergone close scrutiny and have been adopted by >125 countries. Nonetheless, the previous lack of fetal, neonatal, and preterm postnatal growth standards based on the same populations analogous to the WHO’s postnatal standards was viewed as problematic. The lack of international standards led to reliance on multiple references, each describing fetal growth in specific settings (mostly hospital based) and times and without the advantages of common standardization protocols. This has led, unnecessarily, to complications of various types, e.g., disparate interpretation of prevalence rates of small-for-gestational-age infants, and disparities in attributing country- or region-specific morbidity and mortality to that condition (1, 13, 48). The INTERGROWTH-21st Project offers solutions to those shortcomings.

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project’s gestational-age–specific newborn standards, its strict protocol for determining gestational age, and the availability of cross-sectional and longitudinal data for term and preterm infants across its diverse sites enable substantial improvements in regional and global prevalence estimates of diverse outcomes. They also provide relevant research opportunities, e.g., more robust explorations of relations among specific growth trajectories, attained growth characteristics, maternal characteristics, specific fetal and newborn outcomes, and specific phenotypes of prematurity. Each of them, in turn, represents prospects to better assess therapeutic responses of infants born small for gestational age or prematurely and to better understand maternal conditions that adversely affect the developing fetus (37, 49–52).

Notwithstanding the WHO standards’ initial successes and growing interest worldwide in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project’s early publications, 2 concerns are commonly expressed regarding the published international standards. These relate to the genetic dimensions of growth and to the relevance of prescriptive-based standards to populations that experience high rates of stunting.

The first common question is formulated as follows, “How is the observed similarity in growth possible given the enrolled populations’ perceived diverse genetic backgrounds, e.g., Norway and India?” The genetic regulation of growth is well documented: clearly, tall parents tend to have tall children and short parents tend to have short children. That common observation, however, is the consequence of interindividual genetic differences, and it is valid within both the Norwegian and the Indian populations, rather than interpopulation genetic variation. Indeed, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have found ~200 genes associated with stature (31). Those genes collectively explain ∼10% of observed variability in the stature of the GWAS’ populations. That small proportion of explained variation in stature likely reflects difficulties of detecting genes with yet weaker individual effects and/or the limited attention given, to date, to possible roles of other regulatory mechanisms, e.g., those based on structural variation and epistasis (53, 54). The low proportion of variation explained by GWAS also may reflect unaccounted-for differences in nutrition, care, and environmental conditions experienced by subjects enrolled in GWAS studies. The magnitude of this proportion is in agreement with the low percentage of the total variation attributable to interpopulation variance observed by the MGRS and the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium projects in which any of the aforementioned conditions were standardized.

The second common question is related to the appropriateness of using prescriptive-based standards in historically undernourished populations. This, in turn, stems from at least 2 concerns. One relates to possible adverse effects on adult health of promoting rapid growth in early life in those populations and the other to possible transgenerational constraints on growth in children of parents or possibly even grandparents who were undernourished as children (55, 56). Several reports support the possibility that rapid weight gain in early life leads to a higher risk of childhood obesity and chronic diseases of adult onset, but that failing to redress anthropometric shortcoming in early life may impede cognitive development (49, 57–59). Simultaneous changes in stature often are omitted in such analyses. On the other hand, there are data suggesting that rapid simultaneous and proportional gains in weight and stature do not present similar risks (60). Furthermore, I am unaware of any data suggesting that catch-up growth characterized by proportional gains in length and weight results in increased risk to either childhood obesity or chronic diseases of adult onset.

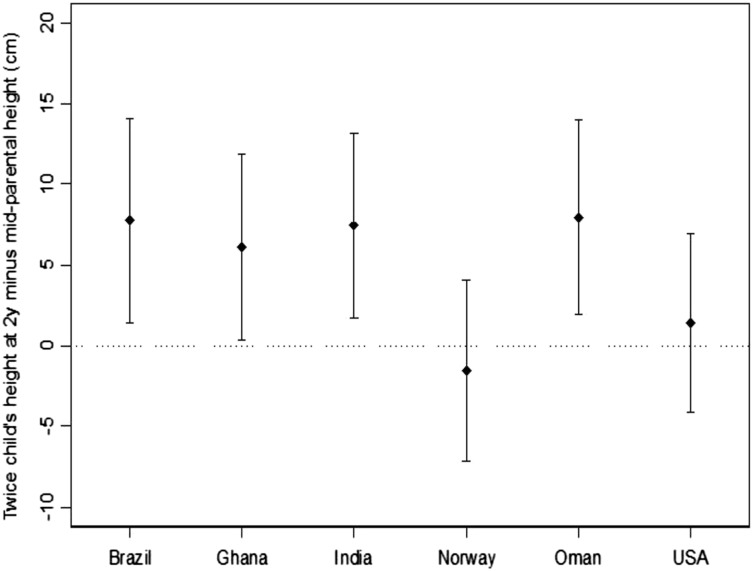

Colleagues and I (61) recently examined limited aspects of the second concern related to putative transgenerational constraints on growth in children of parents who were undernourished in childhood. That investigation compared the MGRS children’s predicted adult heights with the average of their parents’ heights. The children’s predicted adult height was estimated by doubling the children’s length measured at 2 y of age (with corrections for the conversion of lengths to heights). We predicted no differences would be observed between the children’s estimated adult heights and the corresponding mid–parental heights for the Norwegian and United States sites but significant differences in the children’s favor in the remaining 4 sites, i.e., in the sites more likely to include parents who were less adequately nourished as children: Brazil, Ghana, India, and Oman. The findings matched our predictions (Figure 3). The vertical axis shown in Figure 3 summarizes site-specific differences between the children’s predicted adult heights and the mean heights of the children’s mothers and fathers. As predicted, differences for Norway and the United States were zero but significantly positive in the remaining 4 sites. The substantial similarities in the children’s length across all sites at all ages examined were consistent with the conclusion that the children’s adult heights also will be similar. These findings support the expectation that stature can be normalized in one generation, at least in populations with degrees of parental short stature that are similar to those of communities enrolled in the MGRS. They also reinforce the likelihood that secular trends in growth reflect, in part, rates at which health and economic progress permeate impoverished populations rather than unavoidable biological constraints.

FIGURE 3.

Means (points) and SDs (bars) of the difference between 2 times the height of the child at 2 y and the mid–parental height by site. Reproduced from reference 61 with permission.

In conclusion, the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and MGRS present the world with clear norms that are based on what can be achieved in communities when growth needs are met. The community-based approach to sampling and the international framework used by the 2 studies support the view that their findings describe achievable goals that are within biological reach. The caveat is that needs for normal growth must be met from early gestation through at least 5 y of age. Additionally, it is important to recognize that normalized growth is not sufficient to assure desired levels of health and development. It is, nonetheless, a necessary and important goal given the short- and long-term consequences of constrained growth imposed by poor nutrition, environments, and/or care. “Universal norms” for assessing stature and other anthropometric characteristics, similar to most other areas of medicine, are now available, and holding ourselves accountable for attaining them is the responsible choice available to the global health community.

Acknowledgments

I thank José Villar and Stephen H. Kennedy of the Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Oxford Maternal & Perinatal Health Institute, Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, and Dr. Mercedes de Onis, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO, for their generous and careful review of the manuscript for accuracy. The sole author had responsibility for all parts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: BL, birth length; CRL, crown-rump length; FHC, fetal head circumference; GWAS, genome-wide association study; INTERGROWTH-21st, International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century; MGRS, Multicentre Growth Reference Study; SSD, standardized size difference.

References

- 1.Papageorghiou AT, Kennedy SH, Salomon LJ, Ohuma EO, Ismail L, Barros FC, Lambert A, Carvalho M, Jaffer YA, Bertino E, et al. . International standards for early fetal size and pregnancy dating based on ultrasound measurement of crown-rump length in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;44:641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Ismail L, Victora C, Ohuma E, Bertino E, Altman D, Lambert A, Papageorghiou A, Carvalho M, Jaffer Y, et al. . International standards for newborn weight, length and head circumference according to gestational age and sex. Lancet 2014;384:857–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards. Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, and body mass index-for-age. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards. Head circumference-for-age, arm circumference-for-age, triceps skinfold-for-age, and subscapular skinfold-for-age. Methods and development. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards. Growth velocity based on weight, length, and head circumference. Methods and development. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papageorghiou AT, Ohuma EO, Altman DG, Todros T, Ismail L, Lambert A, Jaffer YA, Bertino E, Gravett MG, Purwar M, et al. . International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements. Lancet 2014;384:869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.USAID Press Office. 1000 Days: change a life, change the future. USAID. 20010. [cited 2014 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/1000-days-change-life-change-future.

- 8.Fogel R. Economic growth, population theory, and physiology: the bearing of long-term processes on the making of economic policy. Nobel Prize Committee. 1993. [cited 2014 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1993/fogel-lecture.html.

- 9.Hoddinott J, Alderman H, Haddad L, Horton S. The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Penn Libraries, University of Pennsylvania. 2013. [cited 2013 Oct 30]. Available from: http://repository.upenn.edu/gcc_economic_returns/8/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Deaton A. Height, health, and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:13232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garza C, de Onis M. Rationale for developing a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uauy R, Casanello P, Krause B, Kuzanovic J, Corvalan C; International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 2st Century. Conceptual basis for prescriptive growth standards from conception to early childhood: present and future. BJOG 2013;120(Suppl 2):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villar J, Altman D, Purwar M, Noble J, Knight H, Ruyan P, Ismail L, Barros F, Lambert A, Papageorghiou A, et al. . The objectives, design, and implementation of the Intergrowth-21st Project. BJOG 2013;120(Suppl 2):9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango A, Martorell R, (Eds). WHO growth standards. Acta Pediatrica 2006;95(Supp 450):1–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study Group. Enrollment and baseline characteristics in the WHO Multicentre Growth Refeference Study. Acta Paediatr 2006;95(Suppl 450):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Van den Broeck J, Cameron WC, Martorell R. Measurement and standardization protocols for anthropometry used in the construction of a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eskenazi B, Bradman A, Finkton D, Purwar M, Noble J, Pang R, Burnham O, Cheikh Ismail L, Farhi F, Barros FC, et al. . A rapid questionnaire assessment of environmental exposures to pregnant women in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG 2013;120:(Suppl 2):129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Meer K, Heymans HSA, Zijlstra WG. Physical adaptation of children to life at high altitude. Eur J Pediatr 1995;154:263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen GM, Moore LG. The effect of high altitude and other risk factors on birthweight: independent or interactive effects? Am J Public Health 1997;87:1003–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Araújo CL, Albernaz E, Tomasi E, Victora CG. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in Brazil. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lartey A, Owusu WB, Sagoe-Moses I, Gomez V, Sagoe-Moses C. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in Ghana. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhandari N, Taneja S, Rongsen T, Chetia J, Sharma P, Bahl R, Kashyap DK, Bhan MK. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in India. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baerug A, Bjoerneboe GA, Tufte E, Norum KR. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in Norway. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakash NS, Mabry RM, Mohamed AJ, Alasfoor D. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in Oman. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ. Implementation of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study in the United States. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(1 Suppl):S84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. Breastfeeding in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr 2006;95(Supp 450):16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villar J, Papageorghiou A, Pang R, Ohuma E, Ismail L, Barros F, Lambert A, Carvalho M, Jaffer Y, Bertino E, et al. . The likeness of fetal growth and newborn size across non-isolated populations in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study and Newborn Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:781–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Group. Assessment of differences in linear growth among populations in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr 2006;95(Supp 450):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Ward R. Race and genomics. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorde LB, Wooding SP. Genetic variation, classification and 'race’. Nat Genet 2004;36(11 Suppl):S28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lettre G. Recent progress in the study of the genetics of height. Hum Genet 2011;129(5):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Habicht JP, Martorell R, Yarbrough C, Malina RM, Klein RE. Height and weight standards for preschool children. How relevant are ethnic differences in growth potential? Lancet 1974;1:611–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhandari N, Bahl R, Taneja S, de Onis M. Growth performance of affluent Indian children is similar to that in developed countries. Bull World Health Organ 2002;80:189–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owusu WB, Lartey A, de Onis M, Onyango AW, Frongillo EA. Factors associated with unconstrained growth among affluent Ghanaian children. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:1115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Onis M, Onyango A, Borghi E, Siyam A, Blossner M, Lutter C; WHO Multicenter Growth Study Group. Worldwide implementation of the WHO Child Growth Standards. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of well-being. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2004;359:1359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Maternal constraints of fetal growth and its consequences. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2004;9:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuhb D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waterland RA, Garza C. Potential mechanisms of metabolic imprinting that lead to chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:179–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Mitchell MD. Developmental origins of health and disease: reducing the burden of chronic disease in the next generation. Genome Med 2010;2:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JH, Stoffers DA, Nicholls RD, Simmons RA. Development of type 2 diabetes following intrauterine growth retardation in rats is associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1. J Clin Invest 2008;118:2316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango A, Borghi E. Comparison of the WHO Child Growth Standards and the CDC 2000 Growth Charts. J Nutr 2007;137:144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saha KK, Frongillo EA, Alam DS, Arifeen SE, Persson LÅ, Rasmussen KM. Use of the new World Health Organization child growth standards to describe longitudinal growth of breastfed rural Bangladeshi infants and young children. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salomon LJ, Bernard JP, Duyme M, Buvat I, Ville Y. The impact of choice of reference charts and equations on the assessment of fetal biometry. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005;25:559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dijk CE, Innis SM. Growth-curve standards and the assessment of early excess weight gain in infancy. Pediatrics 2009;123:102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lapidus N, Luquero FJ, Gaboulaud V, Shepherd S, Grais RF. Prognostic accuracy of WHO growth standards to predict mortality in a large-scale nutritional program in Niger. PLoS Med 2009;6:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ioannou C, Talbot K, Ohuma E, Sarris I, Villar J, . Conde-Agudelo A, Papageorghiou AT. Systematic review of methodology used in ultrasound studies aimed at creating charts of fetal size. BJOG 2012;119:1425–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown LD, Hay WW. The nutritional dilemma for preterm infants: how to promote neurocognitive development and linear growth, but reduce the risk of obesity. J Pediatr 2013;163:1543–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imdad A, Bhutta A. Nutritional management of the low birth weight/preterm infant in community settings: a perspective from the developing world. J Pediatr 2013;162:S107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2010;362:529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leon D. Commentary: the development of the Ounsteads’ theory of maternal constraint-a critical perspective. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frazer KA, Murray SS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 2009;10:241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lettre G. Genetic regulation of adult stature. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martorell R, Zongrone A. Intergenerational influences on child growth and undernutrition. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:302–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsen TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1802–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ekelund U, Ong KK, Linne Y, Neovius M, Brage S, Dunger DB, Wareham NJ, Rossner S. Association of weight gain in infancy and early childhood with metabolic risk in young adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115:1367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaquet D, Deghmoun S, Chevenne D, Collin D, Czernichow P, Levy-Marchal C. Dynamic change in adiposity from fetal to postnatal life is involved in the metabolic syndrome associated with reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 2005;48:849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garza C, Borghi E, Onyango AW, de Onis M; WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. Parental height and child growth from birth to two years in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference. Matern Child Nutr 2013;9(Suppl 2):58–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]