Abstract

Cholinergic signaling plays an important role in regulating the growth and regeneration of axons in the nervous system. The α7 nicotinic receptor (α7) can drive synaptic development and plasticity in the hippocampus. Here we show that activation of α7 significantly reduces axon growth in hippocampal neurons by coupling to G protein regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth 1 (Gprin1), which targets it to the growth cone (GC). Knockdown of Gprin1 expression using RNAi is found sufficient to abolish the localization and calcium signaling of α7 at the GC. In particular, α7/Gprin1 interaction appears intimately linked to a Gαo, GAP-43, and CDC42 cytoskeletal regulatory pathway within the developing axon. These findings demonstrate that α7 regulates axon growth in hippocampal neurons, thereby likely contributing to synaptic formation in the developing brain.

Keywords: Choline, axon growth, G protein regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth, hippocampus, synaptic maturation, cytoskeleton

Introduction

In the adult nervous system, neurotransmitters play a central role in driving communication between neurons. In the developing nervous system, neurotransmitters such as serotonin and acetylcholine (ACh) contribute to various phases of development including neurogenesis, cell differentiation, and the formation of synapses (Erskine & McCaig 1995, Rudiger & Bolz 2008). The cerebral cortex and hippocampus receive acetylcholine (ACh) innervation from the basal forebrain, medial septum, and vertical diagonal band (Bruel-Jungerman et al. 2011). Beginning prenatally and continuing through early adulthood, the cholinergic signal informs neural connectivity by modulating the growth and retraction of axons (Elsas et al. 1995, Luo & O'Leary 2005) and the formation of local dendritic fields within hippocampal neurons (Campbell et al. 2010, Lozada et al. 2012).

Cholinergic signaling is dependent on the activation of the G protein coupled muscarinic receptor and nAChRs (Jones et al. 2012). In the adult hippocampus, α7 is expressed pre and post synaptically, contributing to GABA and glutamate neurotransmission (Lozada et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2006). While studies show that α7 regulates neural development in the cortex and hippocampus (Lozada et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2006, Coronas et al. 2000), its mechanism of action is ill defined.

Several nAChRs have also been found to interact with G proteins and contribute to intracellular signaling in neurons (Fischer et al. 2005, Kabbani 2007, Paulo et al. 2009, Nordman & Kabbani 2012). Recently, we have shown that coupling to a G protein complex (GPC) consisting of Gprin1, the heterotrimeric GTP binding subunit Gαo, and growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43) enables α7 to regulate neurite growth (Nordman & Kabbani 2012). To determine the role of α7 in brain development, we have examined the effect of α7/Gprin1 interaction in cultured hippocampal neurons. We find that α7 activation contributes to calcium signaling and inhibition of axon growth via a Gprin1 pathway.

Materials and methods

Neuronal cultures, transfection, and drug treatment

Primary hippocampal neurons were obtained from postnatal day 1 (P1) male/female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) as described (Nunez 2008) according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and ARRIVE regulations. Neuronal cultures were grown in Neurobasal media with B27 supplement and 1% Penstrep. Serum was withdrawn 12 hrs after plating in order to minimize glial growth. A knockdown in α7 expression (α7-) was obtained by transducing high-titer lentiviral stocks of short hairpin RNAs representing α7 RNAi (Lozada et al. 2012) into hippocampal neurons. A scrambled α7 RNAi was used as a transduction control (Lozada et al. 2012). Knockdown in Gprin1 expression (Gprin1-) was obtained by transfecting Gprin1 siRNA in pRNAT H1.1 into hippocampal neurons. Gprin1 vectors have been described previously (Ge et al. 2009, Nordman & Kabbani 2012). Neurons were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Unless otherwise stated, an empty plasmid corresponding to the transfected protein vector was used as a control in the assay.

Drug concentrations were determined based on published studies (Khiroug et al. 2002, Chan & Quik 1993, El Kouhen et al. 2009, Strittmatter et al. 1994, Swarzenski et al. 1996): α-Bungarotoxin (Bgtx) (50 nM, Sigma); PNU282987 (PNU) (1–10 µM, Sigma); pertussis toxin (Ptx) (1 µM, Calbiochem); mastoparan (30 µM, Tocris); choline (1 mM, Acros). Drug treatment experiments were performed in triplicate and the data presented represents the average for each condition. Prior to initiation of the assay, the effect of drug concentration on cell viability and health was pre-established using trypan blue (EMD).

Immunochemical detection of proteins in brain slices and cultured cells

Hippocampal brain slice preparation and immunohistochemistry was preformed as described (Lozada et al. 2012). Briefly, P5 and P30 rats were anesthetized using 5% isofluorane and then perfused using 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.2. Brains were dissected and submerged in the paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours before being transferred to 30% sucrose for cryoprotection. The tissue was then embedded in 5% agarose and sectioned into 30 µm slices using a vibrating blade microtome (Thermo Scientific). For immunohistochemistry, brain slices were permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 and quenched by 50 mM ammonium chloride for 30 min at room temp. Tissue was blocked in 10% goat serum prior to being probed with the α7 ligand fluorescein-conjugated Bgtx (fBgtx) (Molecular Probes), a polyclonal rabbit anti-Gprin1 antibody (Ab) (Abcam), and a polyclonal mouse anti-Tau-1 Ab (Millipore) overnight at 4°C. Tissue was reblocked in 10% goat serum followed by a Dylight 560 secondary anti-rabbit Ab and an Alexafluor 647 secondary anti-mouse Ab for Gprin1 and Tau-1 detection respectively (Jackson-ImmunoResearch). Background autofluorescence was accounted for using the secondary Ab alone.

Cellular immunostaining was carried out as described in (He et al. 2005). Briefly, cultured neurons were fixed in 1× PEM (80 mM PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 6.8) containing 0.3 % glutaraldehyde and then permeabilized at room temperature in 0.05% Triton-X 100 prior to glutaraldehyde quenching with 10 mg/ml sodium borohydride. Cells were blocked in 10 mg/ml BSA + 10% goat serum prior to being immunostained overnight at 4°C with the following primary Abs: mouse anti-Tau-1; anti-Gprin1; pGAP-43; GTP-CDC42 (New East). Secondary Abs used (all purchased from Jackson-ImmunoResearch): carbocyanine (Cy) 2/3; Dylight 488; Dylight 560; and AlexaFluor 647. α7 were visualized using fBgtx. F-actin was visualized using Rhodamine Phalloidin (Cytoskeleton). All staining was visualized using a Nikon Eclipse 80i confocal microscope fitted with a Nikon C1 CCD camera and images captured using AxioVision and EZ-C1 software.

For protein distribution analysis in immunostainings, brain slices and cells in culture were analyzed for colocalization and distribution of α7 and Gprin1 by first threshholding the individual signals to reduce background (Lozada et al. 2012) and then merging the two signals using ImageJ (NIH). For brain slices, the colocalized α7/Gprin1 signal was measured in various compartments according to overlap with DIC. Distribution analysis was conducted by measuring the signal within a 1 µm2 area for neurons or a 25 µm2 area for brain slices sufficient for analysis at the single neuron level. Analysis was conducted in Tau-1 positive (Tau-1+) cultured hippocampal neurons. All data is based on averages from three separate independent experiments.

Protein isolation and detection

Solubilized membrane protein fractions (membrane proteins) of hippocampal cells were obtained using a published protocol optimized for nAChRs (Kabbani et al. 2007). Immunoprecipitation (IP) of receptor-protein complexes for α7 was optimized and described previously (Nordman & Kabbani 2012). In brief, proteins were solubilized overnight at 4°C using a solution of 1% Triton X-100, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 8) with a 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete) and a 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Protein concentrations were obtained using the Coomassie Protein Assay reagent (Thermo). IP experiments were performed by first incubating membrane proteins with an anti-α7 monoclonal Ab (mAb306, (Lindstrom et al. 1990)) or an anti-Gprin1 rabbit polyclonal Ab (Abcam) followed by extraction using protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen). Control IP experiments were performed by incubating the same amount of membrane proteins (MP, 100 µg) with an equal amount of a pure polyclonal rabbit IgG Ab (5 µg) (Cell Signaling).

Western blot detection was obtained using nitrocellulose membranes blocked with 5% nonfat milk (or 1% BSA for biotinylation experiments). Membranes were probed with the following primary Abs overnight at 4°C: α7 nAChR (SC); Gprin1; HCN1 (SC); GAP-43 (Abcam); pGAP-43; CDC42 (SC); GTP-CDC42; GAPDH (Cell Signaling). Species-specific peroxidase conjugated secondary Abs were purchased from (Jackson- Immunoresearch). Signals were detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) with SeeBlue and MagicMark (Invitrogen) as molecular weight standards. Blots were imaged using the Gel Doc Imaging system (Bio-Rad). Band density analysis was performed using ImageJ version 10.2 (NIH). Western blot values are based on averages from three separate independent experiments.

Growth cone purification

Isolation of growth cone (GC) compartments was performed as described (Lohse et al. 1996). In brief, hippocampi pooled from a litter of P0 rat pups were homogenized in 1 mM TES buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 51 mM NaCl) supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, 0.32 M sucrose, and protease (Complete) and phosphatase (Sigma) inhibitors. The homogenate was spun at low speed centrifugation (1660 × g) and the supernatant was collected then layered over a sucrose gradient of 0.83 M and 1.0 M. Layered sample was then centrifuged at 242000 × g for 40–60 min at 4°C. The GC fraction was found at the 0.83 M interface while the cell fraction (CF) was found at the 0.83–1.0 M fraction. GC proteins were solubilized for membrane protein enrichment using the method described above.

Biotinylation of cell surface receptors

The quantification of proteins at the cell surface was conducted using a biotinylation protocol (Kabbani et al. 2002, Hannan et al. 2008). In these experiments 300 µg/mL EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) was used to label cell surface proteins in living cells for 30 min at 4°C. The biotin reaction was quenched using Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS) and membrane proteins were prepared as described previously (Kabbani et al. 2007). A neutravidin agarose bead matrix (Pierce) was used to pulldown biotinylated proteins over a 30 µm pore size Snap Cap spin column (Pierce). Proteins were detected using western blot as described above. Biotin labeling was detected using HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Cell Signaling). Experiments were performed in triplicate and the data presented is the group averages.

Morphological and statistical analysis

Morphological reconstruction was performed using Neuromantic software (Myatt & Nasuto 2008). Tau-1+ axons were measured for surface area (SA) and branch number to assess size and complexity under various conditions. Only the primary axon was analyzed in each neuron. Neurons were readily visualized by Tau-1+ staining, and GCs were visualized by reactivity to rhodamine phalloidin. Group averages were derived from three separate experiments with 20–30 cells represented in each. Statistical analysis was conducted on raw data of image tracing using Neuromantic. Statistical values have been obtained using a Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. Asterisks indicate statistical significance in a paired Student’s t test, two tailed P value, *<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

EB3 comet imaging

End binding protein 3 (EB3) is a microtubule capping protein that binds to the plus end of polymerized microtubules during periods of assembly (Stepanova et al. 2003). Hippocampal neuronal cultures were transfected with RFP-EB3 and the indicated cDNA plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 at 60 hours after plating (Liu et al. 2010). EB3 comet imaging was performed 24 hours later. Images were captured 1 frame per sec for 2 min at 2 × 2 binning using Axiovision 4.6. The images were quantified for the velocity of the comets that enter the growth cone filopodia (Nadar et al. 2008). Cells were treated with PNU (1–10 µM), a combination of PNU 10 µM and 50 nM Bgtx, 0.1% DMSO as vehicle control, or an empty vector as a transfection control. The comet trajectories were traced in these experiments using ImageJ software (NIH). Experiments were performed in triplicate and the data presented is the group averages.

Calcium imaging

Calcium imaging was carried out as described previously (Del Negro et al. 2011) with minor modifications. P0 hippocampal neurons were cultured for 3 DIV before loading with the calcium dye Fluo-8 AM (SC). Cultures were washed with HBSS and then incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature in a dye-loading solution containing HBSS with 10mM HEPES, 2.5 µM Fluo-8 AM, and 0.2% Pluronic acid F-127. Following incubation, the cultures were again washed in fresh HBSS and then immediately placed into a recording chamber perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at a rate of 1 ml/min. We imaged Fluo-8 AM-labeled neurons using a fixed-stage Zeiss Axio Examiner A.1 with a 63×/1.0 NA objective and a Rolera EMC2 camera (Q-Imaging) imaged at 10Hz. Phototoxicity was minimized through the use of low-wavelength polarized light filters. Image stacks were acquired at 70 Hz using a CCD camera (Andor Technology). The following drugs and their concentrations were diluted in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) and administered via a perfusion system at 1 ml/min: PNU (10 µM); PNU and Bgtx (50 nM); choline (1 mM); choline and Bgtx. 0.1% DMSO was used as a vehicle control. An empty RFP-vector was used as a transfection control. Regions of interest (ROIs) were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) and normalized as ΔF/F0. ROIs were averaged over conditions. The data presented has been normalized to controls.

Mass spectrometry

Protein analysis was conducted using Liquid Chromatography Electro Spray Ionization (LC-ESI) mass spectrometry (MS). Protein complexes were prepared as described (Kaiser et al. 2008) and mass spectrometry was carried out using a published protocol (de Luca et al. 2009). Tandem mass spectra collected by Xcalibur (version2.0.2) were searched against the NCBI rat protein database using SEQUEST (Bioworks software from ThermoFisher, version 3.3.1). The SEQUEST search results were filtered using the following criteria: minimum X correlation (XC) of 1.9, 2.2, and 3.5 for 1+, 2+, and 3+ ions, respectively, and ΔCn > 0.1. The Protein Score (PS) represents the XC where scores <0.1 were excluded from the analysis and does not reflect the quantity of a protein in the sample.

Results

α7 and Gprin1 interact in the developing hippocampus

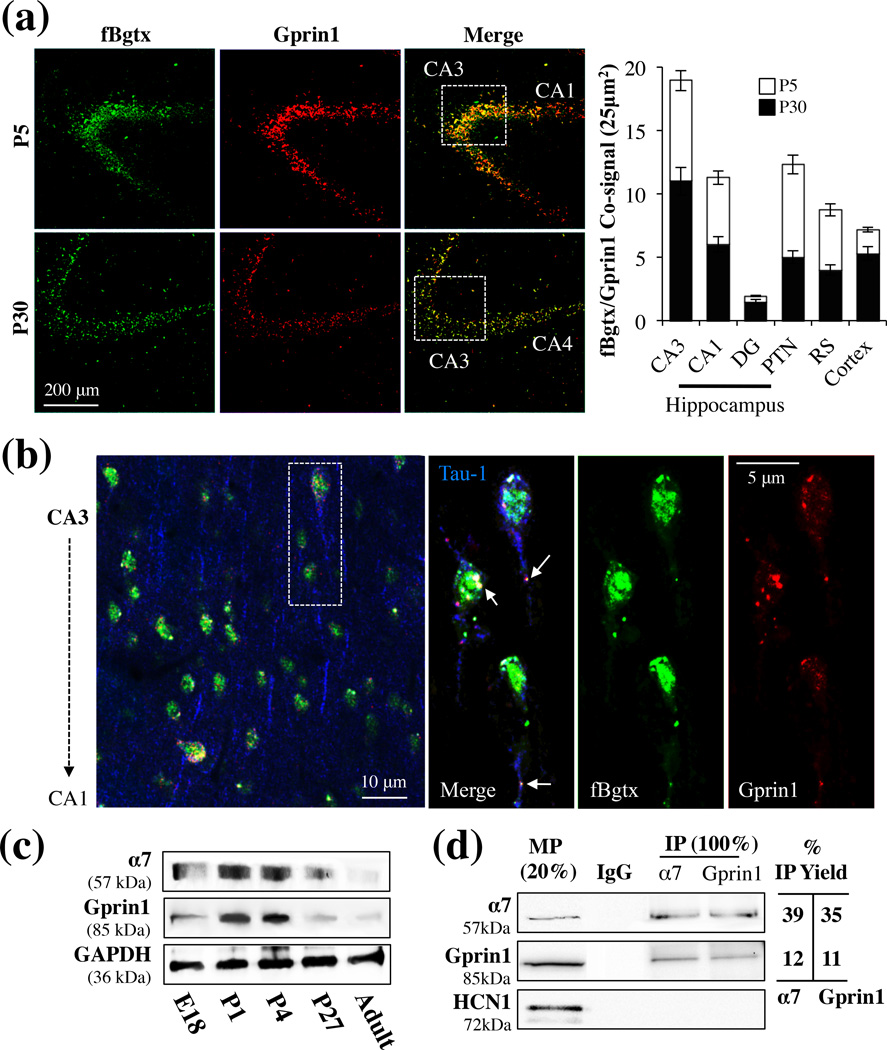

α7 is expressed in the adult hippocampus where it can modulate the activity of excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Albuquerque et al. 1996, Albuquerque et al. 1998). In hippocampal development however less is know about the expression and role of α7. We examined the distribution of α7 in the hippocampus at various stages of growth. Brains from postnatal day (P) 5 and 30 rats were probed for α7 expression using fluorescent conjugated α-bungarotoxin (fBgtx). Additionally, we co-immunolabeled the brain slices with an anti-Gprin1 Ab, which selectively recognizes Gprin1 (Nordman & Kabbani 2012). As shown in Fig. 1a, co-expression of fBgtx and Gprin1 was detected in the developing hippocampus. This expression, while widespread, was not ubiquitous. In particular, the Gprin1 signal was found in cells that were immunoreactive for the axon specific marker Tau-1 while fBgtx labeling was detected in Tau-1+ cells (Fig. 1b) as well as those that exhibited immunoreactivity to the astrocytic marker GFAP (data not shown). These findings imply that while α7 expression in not limited to neurons, Gprin1 expression is predominantly neuronal.

Fig. 1.

α7 and Gprin1 interact in the developing hippocampus. (a) Coronal slices of brains obtained from P5 and P30 rats. Slices were co-labeled with fBgtx and anti-Gprin1 Abs and visualized throughout the hippocampus, with prominent expression found in the CA3 region. Quantification of the co-signal in various brain regions is shown in the histogram. (b) Triple labeling for Tau-1 (blue), fBgtx (green), and Gprin1 (red) in CA3 at P5. Arrows point to colocalization of fBgtx and Gprin1 in soma and axons. (c) Western blot detection of α7 and Gprin1 in membrane protein (MP) fractions of the hippocampus. The same blot was used to probe for α7, Gprin1, and GAPDH as a loading control. (d) Western blot detection of α7 and Gprin1 interactions from P0 pups within IP experiments. In-gel digest confirms the identity of α7 and Gprin1 in the IP (Table S1). Top blot: α7; middle blot: Gprin1; bottom blot: HCN1. MP 20%: membrane protein as 20% of IP load (100 µg). IgG: IP control. IP Yield: amount of IP protein obtained as determined by the equation: optical density (O.D.) of IP bands/OD of 100% MP×100.

We compared the expression of the two proteins during development. A fluorescence double signal (co-signal) for fBgtx and anti-Gprin1 within the cell was measured as previously described (Nordman & Kabbani 2012). In preliminary experiments, the fBgtx signal was diminished by the addition of PNU (1 and 10 µM), confirming the specificity of the ligands on the α7 (Fig. S1). As shown in Fig.1a, the co-signal was of greater abundance during the early P5 stage of development. A quantitative assessment of the fluorescence co-signal was used to determine α7/Gprin1 coexpression in the hippocampus. As shown in Fig. 1a, anoticeable α7/Gprin1 co-signal was detected in CA3 and CA1 regions at P5. Immunolabeling with an anti-Tau-1 Ab confirmed that over 95% of the cells that displayed an α7/Gprin1 co-signal are neurons (Fig. 1b). Hippocampal neurons are known to undergo apoptosis, maturation, and synaptic pruning during early postnatal development (Jordan et al. 1997, Riccomagno et al. 2012). α7/Gprin1 coexpression was also detected in other regions of the hippocampus as well as the cortex and striatum (Fig. 1a). Single labeling experiments using fBgtx, anti-Tau-1, or anti-Gprin1 antibodies produced a signal consistent with the double and triple labeling results (data not shown).

Immunofluorescent findings indicate that α7/Gprin1 expression is highest after birth. To explore this, we examined the levels of the two proteins in hippocampal tissue by western blot. As indicted in Fig. 1c, the expression of α7, within membrane fractions of the developing hippocampus, appeared to peak at 1 and 4 days after birth. Similarly, the expression of Gprin1 displayed a consistent expression profile, i.e. peaking after birth then sharply declining to barely detectable levels in adulthood (Fig. 1c). These results suggest a role for the two proteins in hippocampal development.

Immunounoprecipitation was used to validate interactions between α7 and Gprin1 during hippocampal development. Membrane proteins (MP) derived from P5 rat pups were used to immunoprecipitate Gprin1 and α7 proteins. α7 specific Ab mAb306 and an anti-Gprin1 Ab was then used to immunoprobe for Gprin1 and α7 in the IP, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1d, immunoreactive bands for α7 and Gprin1 proteins were detected in the IP experiments. The identity of the proteins within the IP assay was also confirmed in parallel experiments utilizing MS analysis (Table. S1) and previously (Nordman & Kabbani 2012). An hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel type 1 (HCN1) specific Ab was used as a negative control in the IP experiment. As shown, neither of the two IP Abs were found to co-IP the HCN1 in the assay (Fig. 1d) thus supporting the specificity of the interaction between α7 and Gprin1 at the plasma membrane.

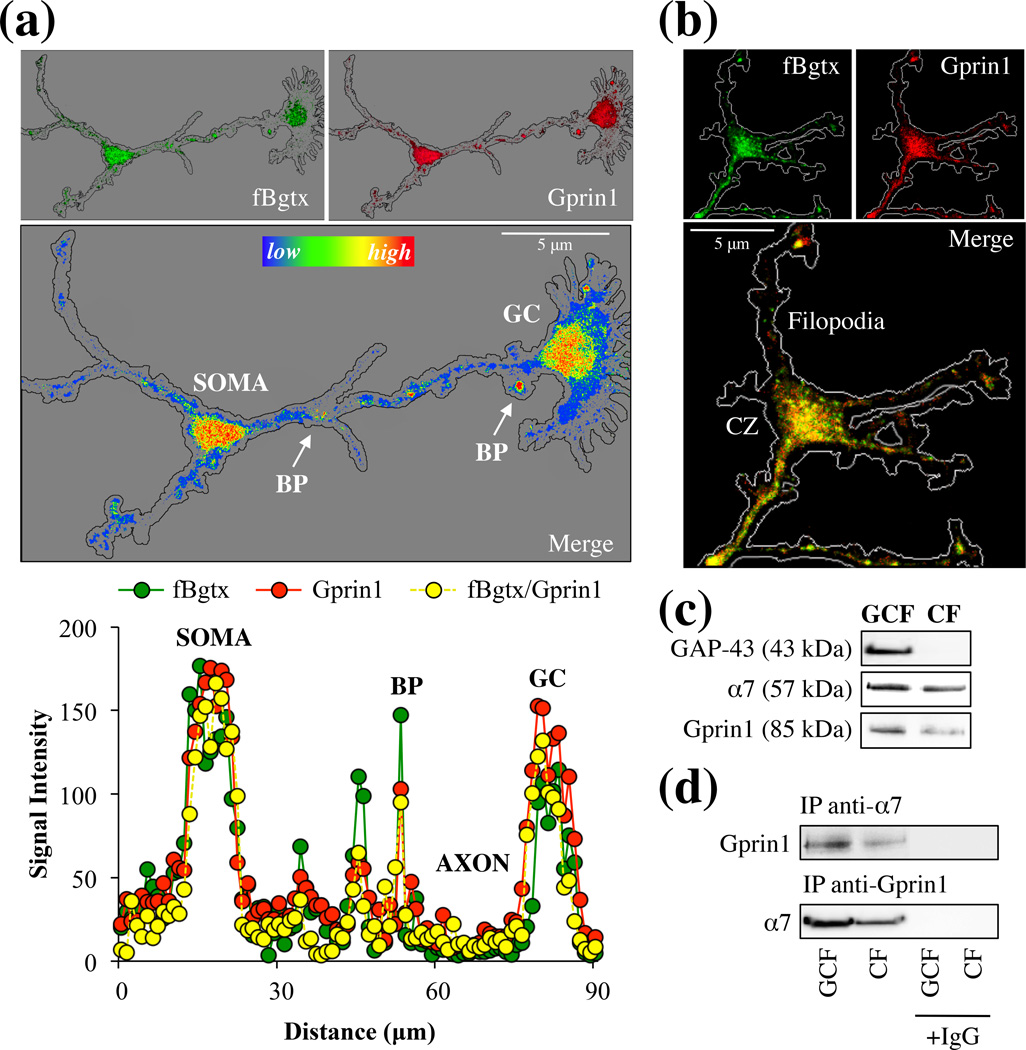

Localization of α7 and Gprin1 in axons and growth cones

We examined expression of endogenous α7 and Gprin1 proteins in developing hippocampal neurons. At 3 days in vitro (DIV) hippocampal neurons extend axons capable of detecting and reacting to various external growth signals (Kater & Mills 1991). As shown in Fig. 2, α7 and Gprin1 proteins were detected within developing hippocampal neurons using fBgtx and anti-Gprin1 Abs, respectively. The specificity of the Gprin1 Ab was verified in preliminary studies that showed a proportional decrease in the Gprin1 Ab signal following transfection with Gprin1 siRNA (data not shown). In particular, strong levels of α7 and Gprin1 coexpression were observed in the soma, at neurite branch points, and in the growth cone (GC) (Fig. 2a). Growth cones and branch points are known to be active regions of growth and retraction (Lowery & Van Vactor 2009). We find that α7/Gprin1 colocalization is highest at these regions of active growth suggestive of a role for the interaction in cytoskeletal remodeling and axon development.

Fig. 2.

α7 and Gprin1 associate in the growth cone. (a) Hippocampal neurons from P0 pups was cultured for 3 DIV. Neurons were probed with fBgtx (green) and anti-Gprin1 Abs (red) (top images). A heat-map measure of the co-signal (bottom image) shows the distribution and co-localization of the two proteins in the growing axon and GC. Colocalization was highest in the soma, growth cone (GC), and branch points (BP) (arrows). (b) Localization of the fBgtx and Gprin1 signals in the GC. CZ: central zone. (c) Protein detection of α7 and Gprin1 within GC fraction (GCF) obtained from P0 pups as described in Materials and Methods. GAP-43 is used as a marker for the GCF. Cell fraction (CF). (d) An anti-α7 and anti-Gprin1 Ab was used to IP α7 and Gprin1 proteins from the GCF. Western blot detection confirms interaction of the two proteins. Protein identity was also determined by in-gel digest mass spectrometry (Table S2). IgG was used as an antibody control.

The axon growth cone consists of 3 main zones: peripheral, transitional, and central. The central zone (CZ) is located at the base of the GC, nearest to the axon, and is composed of microtubules as well as various receptors and organelles (Lowery & Van Vactor 2009). We find strong colocalization of α7 and Gprin1 within the CZ and in some cases, the two proteins were detected in the filopodia of the GC (Fig. 2b). A GC purification strategy (described in Materials and Methods) (Lohse et al. 1996) was utilized to confirm expression and interaction of α7 and Gprin1 in the GC of the developing hippocampus. As shown in Fig. 2c, an anti-GAP-43 Ab was used to confirm the isolation of the GC compartment from hippocampal tissue. A Western blot analysis reveals that α7 as well as Gprin1 are present within the GC consistent with our immunocytochemical finding. The interaction between the two proteins within the IP was also confirmed in parallel using MS analysis (Table S2). The above experiments demonstrate an α7/Gprin1 interaction within the GC of developing hippocampal neurons.

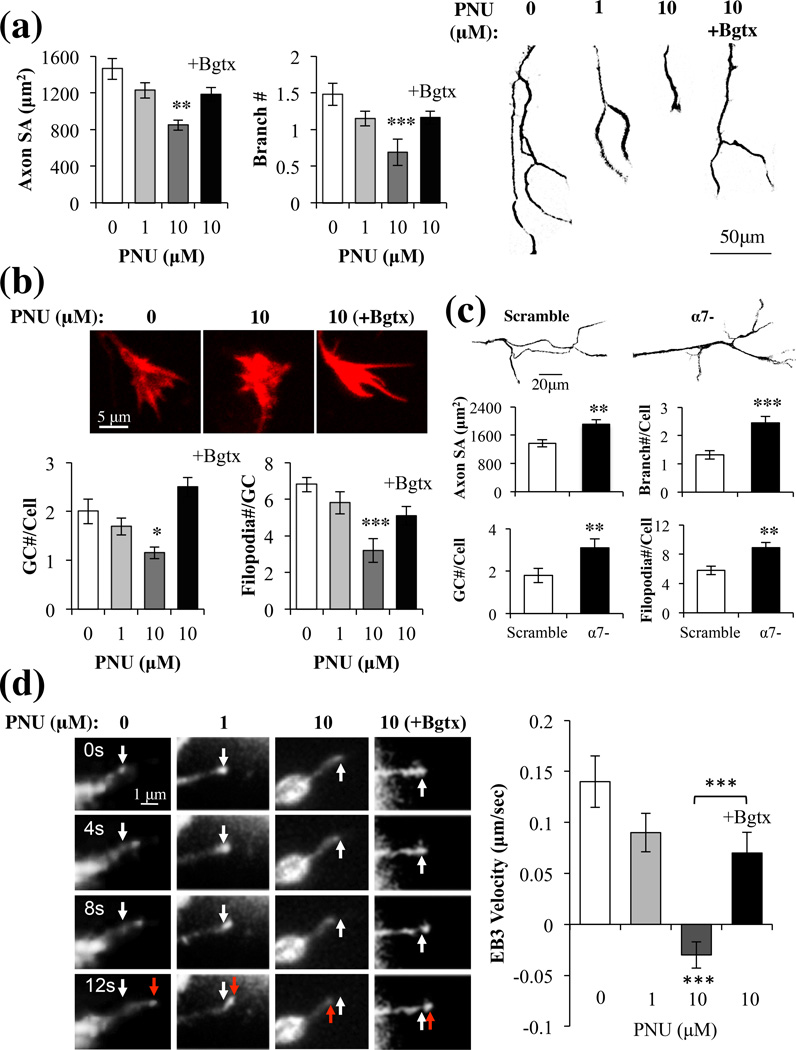

α7 regulates the structure of the growth cone and axon

α7 has been shown to regulate neurogenesis and dendritic as well as axonal synaptic formation in the nervous system (Bromberg et al. 2008b, Lozada et al. 2012). To examine the role of this receptor in early axon growth of hippocampal neurons, we examined the effect of the α7 specific agonist PNU282987 (PNU) on axon size and structure in hippocampal neurons. PNU is a known agonist at the α7 receptor site found to bind other nAChR ligands including Bgtx (El Kouhen et al. 2009). The stability of PNU and its resistance to neurotransmitter reuptake mechanisms make it an ideal experimental tool when attempting to selectively target α7. Newly formed axons were visualized using an antibody for the axon specific microtubule protein Tau-1. We assessed the effects of PNU (1–10 µM) or a combination of PNU (10 µM) and the α7 specific antagonist α-Bungarotoxin (Bgtx) (50 nM) on axon growth. PNU treatment was associated with a significant, dose-dependent (10 µM) reduction in axon growth (−42% (+/− 6%)), measured as total surface area (SA)) and branching number (47% (+/− 7%)) (Fig. 3a). In the presence of Bgtx however, PNU did not significantly alter the growth and complexity of the primary axon relative to control treated cells (Fig. 3a). Group significance was observed between controls and PNU doses (1–10 µM) (SA: F(2,30) = 4.85, p < 0.01; Branch: F(2,30) = 6.12, p < 0.01). These results reveal that pharmacological activation of α7 reduces axon growth and branching in hippocampal neurons.

Fig. 3.

Activation of α7 inhibits axon growth. Hippocampal neurons were treated with multiple doses of PNU or a 0.1% DMSO control (PNU=0). (a) Analysis of surface area (SA) and branch number of Tau-1+ axons (left) represented as phase contrast images (right). (b) Images: GCs stained with rhodamine phalloidin. Histogram: an analysis of the GC. (c) Morphometric analysis of axons and GCs in α7- or scramble cells in the absence of drug treatment. (d) Images: RFP-EB3 comet movement (red arrow) from the starting position (white arrow) within the GC filopodia. Histogram: Changes in EB3 comet velocity with drug treatment. Bgtx (50 nM); Control (0.1% DMSO).

GC dynamics are instrumental in guiding the developing axon towards its final destination and have been shown to be a useful measure of real time growth (Zheng & Poo 2007). In particular the actions of filopodia correlate with the directionality of axonal growth (Lowery & Van Vactor 2009). We find high levels of α7 expression in the GC formation at the end of the primary axon branch (Fig. 2a). We hypothesize a role for α7 in regulating axon growth via the GC. To test this we analyzed the structure of the GC in hippocampal neurons treated with the α7 agonist PNU (1–10 µM). We find a dose dependent reduction in the number of GCs for each neuron (−44% (+/− 10%)) and a reduction in filopodia number and size in each GC (−53% (+/− 11%)) following PNU treatment and compared to vehicle treated controls (Fig. 3b). Group significance was observed between controls and PNU doses (1–10 µM) (GC#/cell: F(2,30) = 5.13, p < 0.01; Filopodia#/GC: F(2,30) = 6.95, p < 0.01). In PNU (10 µM) treated cells, GC and axon morphology were highly correlated (Table S3), suggesting that α7 activation inhibits growth uniformly throughout the cell. Similar to axon growth, Bgtx was found to abolish the effects of PNU (10 µM) on GC structure and number in a highly correlative manner (Fig. 3b, Table S3), underscoring the specificity of the α7 signal in these developmental effects.

To confirm the role of α7 in axon growth, hippocampal neurons were transduced with α7 RNAi or a scramble vector then analyzed for morphology of axon growth in the absence of drug treatment. As shown in Fig. 3c, cells expressing α7 RNAi (α7-) displayed significantly enhanced growth of axons (SA: +39.5% (+/− 9%); Branch number: +85.6% (+/− 10%)) and growth cones (GC number/cell: +72.2% (+/− 16%); Filopodia number/cell: 53.4% (+/− 11%)) compared to both the scramble controls and non-transfected cells (Fig. 3a–c). The scramble vector was found to have no effect on axon growth. Similar findings were observed in hippocampal neurons treated with 50 nM Bgtx showing that inhibition of α7 promotes axon growth (data not shown). In light of earlier findings on PNU mediated inhibition of axon growth, the current data supports the hypothesis that inactivation of α7 can augment neurite growth (Nordman & Kabbani 2012).

We observed the effects of PNU treatment on cytoskeletal growth using the microtubule + end capping protein RFP-EB3 (EB3 comets), which has been utilized in analyzing real time axon growth (Liu et al. 2010, Stepanova et al. 2003). As shown in Fig. 3d, at 1 µM of PNU treatment, EB3 comets velocity was noticeably diminished relative to controls. At 10 µM of PNU however, the velocity of the EB3 comets was not only significantly attenuated but also moved in a retrograde direction suggestive of growth cone collapse. Group significance was observed between controls and PNU doses (1–10 µM) (F(2,30) = 5.80, p < 0.01).The addition of Bgtx was found to significantly attenuate the effects of PNU treatment (10 µM) on EB3 comet velocity, and restored the directionality of comet movement to anterograde (Fig. 3d).

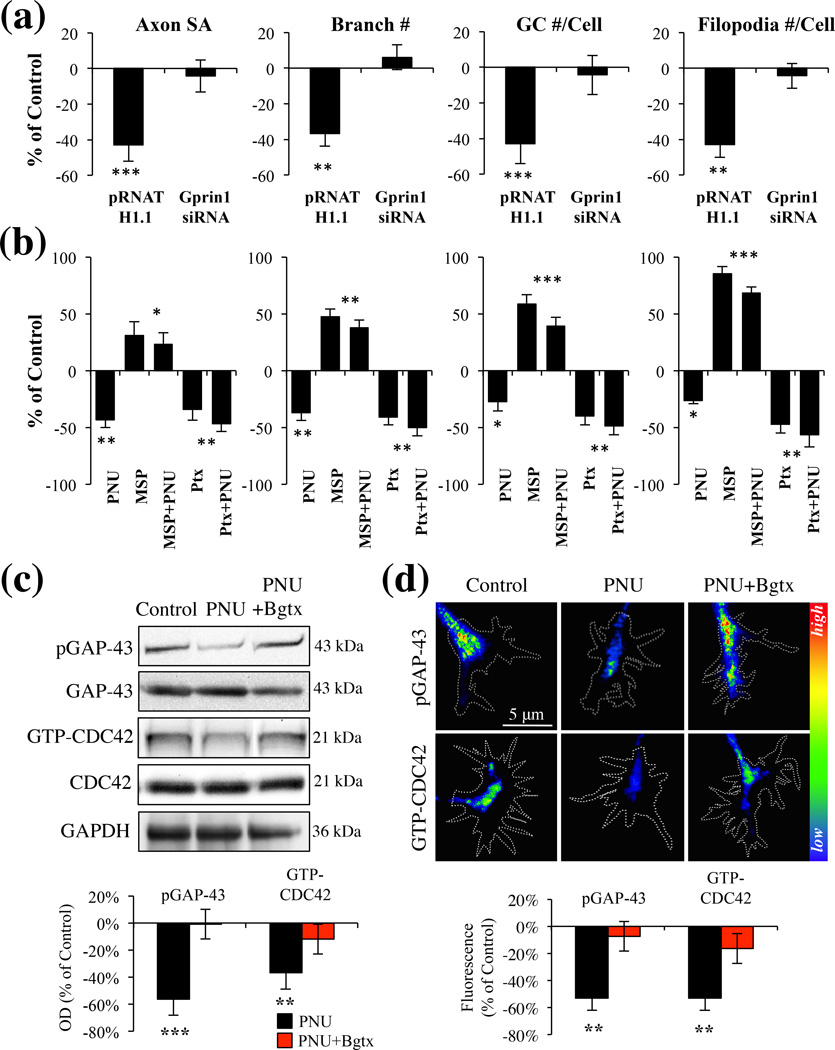

Gprin1 is critical for α7-mediated growth

Gprin1 can regulate neurite growth via its ability to bind and regulate large G proteins such as Gαo, as well as small G proteins such as CDC42 (Chen et al. 1999, Nakata & Kozasa 2005). We determined a role for Gprin1 in α7 mediated axon growth in hippocampal neurons by transfecting neurons with plasmids encoding short interfering RNA (siRNA) (Gprin1-), which has been shown to reduce Gprin1 expression in neural cells (Ge et al. 2009). Consistent with earlier findings reduction in Gprin1 expression was associated with an overall decrease in neurite growth (Ge et al. 2009). When examining the effects of PNU on axon growth, we found that PNU has no effect on the axon morphology in Gprin1- cells (Fig. 4a), suggesting that Gprin1 expression is necessary for α7 function. We confirmed the involvement of Gαo in the α7/Gprin1 pathway. As shown in Fig. 4b, treatment of cells with the Gαo activator mastoparan (MSP) was found to significantly enhance axon growth (axon SA: 31% (+/−11%); branch #: 47% (+/−4%); GC #/cell: 58% (+/−5%); filopodia #/cell: 45% (+/−4%)). The effect of MSP was found sufficient to over-ride PNU mediated inhibition of axon growth suggesting that Gαo operates downstream of α7. We confirmed this by also examining the role of the Gαi/o inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX) on axon development. Ptx exposure was associated with a significant reduction in axon growth (axon SA: −34% (+/−10%); branch #: −41% (+/−7%); GC #/cell: −40% (+/−6%); filopodia #/cell: −47% (+/−8%)) and this effect was not enhanced by PNU. Group significance was observed between controls, MSP, MSP+PNU, Ptx, and Ptx+PNU treated cells (SA: F(4,50) = 5.37, p < 0.01; Branch#: F(4,50) = 12.36, p < 0.001; GC#/Cell: F(4,50) = 12.79, p < 0.001; Filopodia#/Cell: F(4,50) = 14.01, p < 0.001), suggesting that α7 operates in a Gαi/o pathway.

Fig. 4.

α7 mediated inhibition of axon growth is dependent on a Gprin1 pathway. (a) An analysis of axon and GC morphology in cells treated with 10 µM PNU. Values are based on average percent change in axon growth from control cells (cells transfected with the same plasmid but treated with 0.1% DMSO). (b) An analysis of axon and GC morphology in cells treated with: PNU (10 µM); Ptx (1 µM), mastoparan (30 µM) Values are based on average change in axon growth from control cells which were treated with 0.1% DMSO alone. (c–d) Analysis of pGAP-43 and GTP-CDC42 expression within hippocampal neurons treated with PNU (10 µM), PNU+Bgtx (50 nM), or Control (0.1% DMSO) for 60 min in MP (c) and GCs (d). Immunofluoresecence signal in d represented as a heat map.

α7 signaling at the GC regulates GAP-43 and CDC42

A number of signaling pathways have been shown to regulate axon growth or direct its retraction by directing the assembly of the cytoskeleton (Lowery & Van Vactor 2009). Studies demonstrate that activation of GAP-43 via its phosphorylation at Ser41 is critical for axon growth and branching (Leu et al. 2010, Dent & Meiri 1998, Kozma et al. 1997). Similarly the GTP-activation of CDC42 (GTP-CDC42) functions as an important indicator of GC function (Kozma et al. 1997). Recently we have demonstrated that α7 activation regulates GAP-43 phosphorylation in neurites (Nordman & Kabbani 2012), while other studies have shown a role for Gprin1/Gαo in the activation of CDC42 in the growth cone (Nakata & Kozasa 2005). To test the role of α7 signaling in GAP-43 and CDC42 activation, we examined the effect of PNU (60 min treatment) on the phosphorylation of GAP-43 and the levels of GTP-CDC42 in hippocampal neurons. We find a significant reduction in phospho-GAP-43 (pGAP-43) (Zakharov & Mosevitsky 2007) and active (GTP bound) CDC42 (Elbediwy et al. 2012) levels in PNU treated cells (Fig. 4c). Decrease in pGAP-43 and GTP-CDC42 expression was especially pronounced in the GC (Fig. 4d). The effect of PNU on GAP-43 phosphorylation and CDC42 activation was abolished in the presence of Bgtx, suggesting that α7 can inhibit the function of these two growth regulatory proteins.

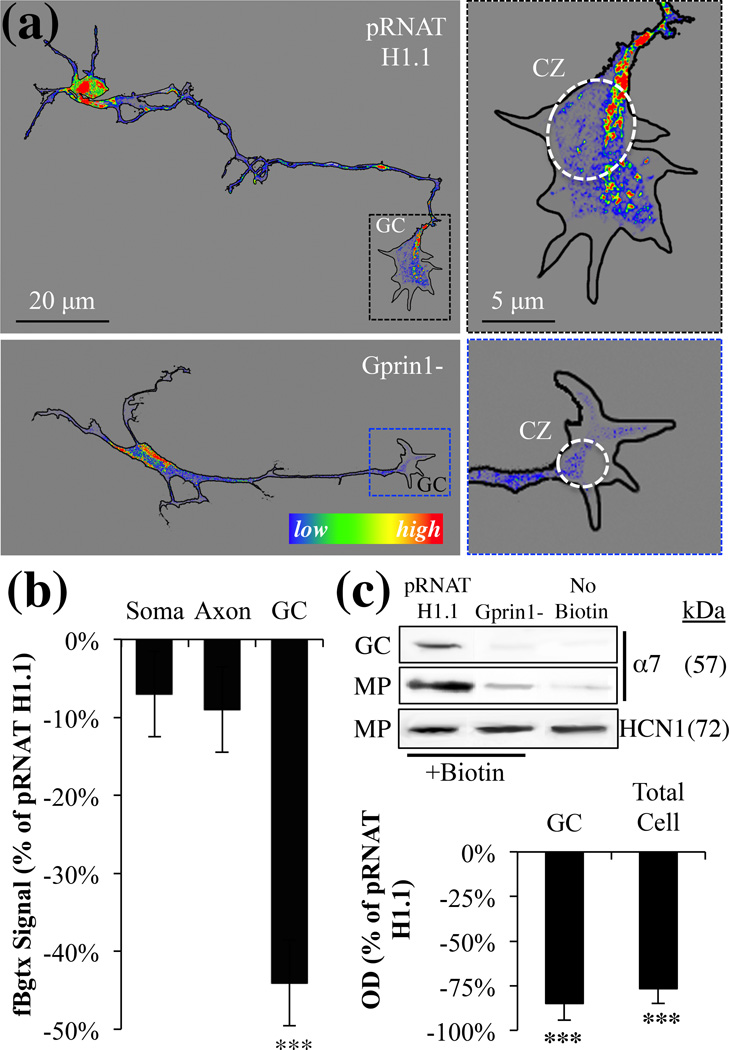

Gprin1 localizes α7 to the growth cone

Gprin1 is a membrane anchored signaling protein that localizes to regions where cytoskeletal remodeling demands are high. In neural cells, Gprin1 can direct the formation of neurites by regulating the function of CDC42 in the growth cone (Nakata & Kozasa 2005). Because recent studies suggest that Gprin1 can also contribute to receptor localization at the cell surface (Ge et al. 2009, Nordman & Kabbani 2012), we examined role of Gprin1 in trafficking and targeting α7 to plasma membrane of the GC. As shown in Fig. 5a–b, Gprin1- cells displayed a significant reduction in the axonal structure, which was accompanied by a noticeable reduction in fBgtx labeling in the GC. To determine the role of Gprin1 in directing α7 to the plasma membrane, cell surface biotinylation experiments were performed in Gprin1- cells and empty vector (pRNAT H1.1) transfected controls. As shown in Fig. 5c, based on the detection of biotinylated α7 proteins, we find a significant reduction in α7 at the cell surface in Gprin1- relative to controls. In both the GC and the membrane protein (MP) fraction, levels of biotinylated α7 proteins was reduced in Gprin1- cells suggesting that Gprin1 plays an essential role in localizing α7 to sites important for axon growth. In these experiments, HCN1 cell surface expression was found unaffected.

Fig. 5.

Gprin1 directs the localization of α7 to the cell surface of the growth cone. (a) pRNAT H1.1/Gprin1- cells were labeled with fBgtx for the visualization of α7 expression. Right panels: magnified images of the GC showing changes in α7 expression within the central zone and filipodia between the two conditions. The fBgtx signal is shown as heat map. (b) A quantification of the fBgtx signal in Gprin1- cells relative to empty pRNAT H1.1 controls. (c) Cell surface biotinylation was used to determine α7 expression at the cell surface in the GC and MP fraction. HCN1 was used as a negative control.

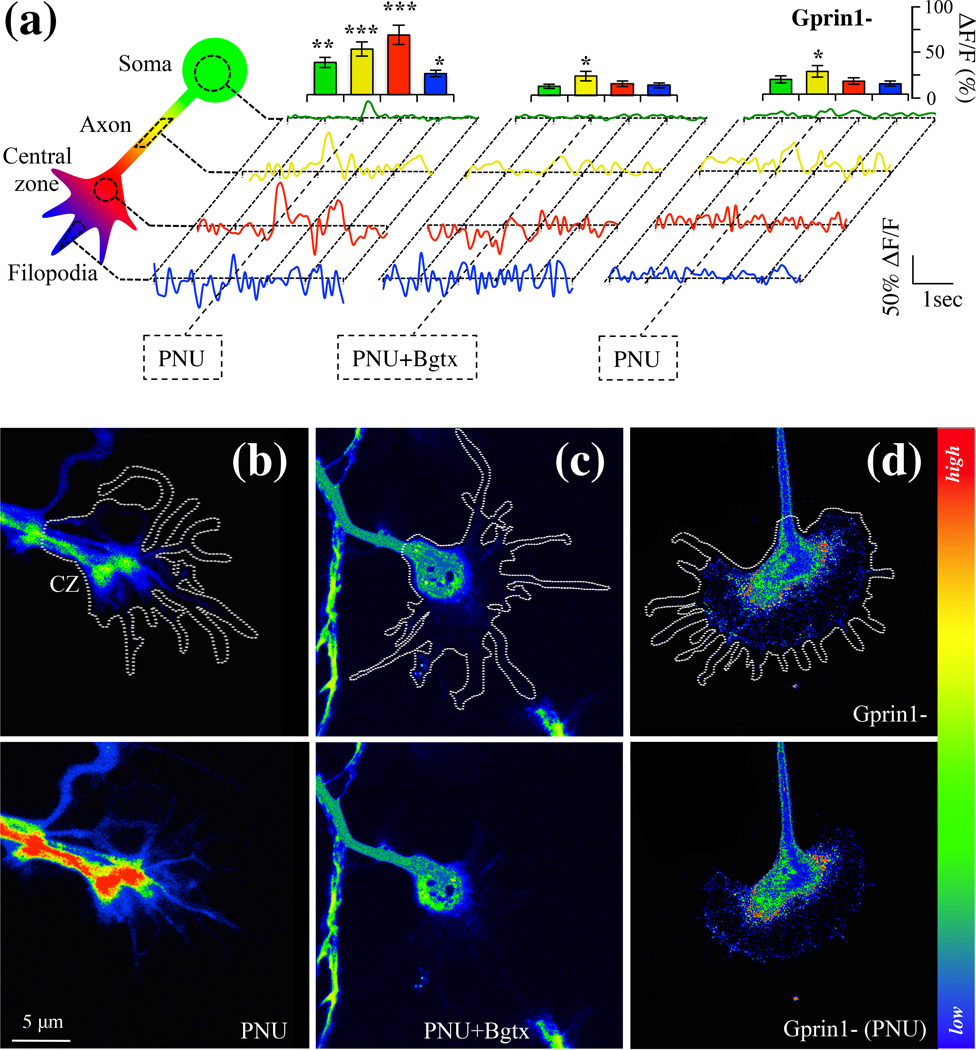

Detection of an α7 calcium signal in the growth cone

Multiple ion channels and receptors contribute to calcium entry and signaling within the GC (Zheng & Poo 2007). The temporal and spatial dynamics of calcium within the GC contributes to the elongation, retraction, and turning of the axon via the actions of molecules such as GAP-43 and Gprin1, which regulate the cytoskeleton (Nakata & Kozasa 2005, Zheng & Poo 2007). We hypothesize that α7/Gprin1 interaction enables calcium signaling leading to cytoskeletal remodeling in the developing axon. To test this we analyzed α7 mediated calcium changes in hippocampal neurons using the calcium indicator Fluo-8 (Hayes et al. 2012). 0.1% DMSO was used as a vehicle control. The control by itself did not appear to impact calcium levels in the cell (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6, PNU treatment was found to promote an overall increase in calcium relative to the control within the soma (+37% (+/− 11%)), the axon (+52% (+/− 14%)), and the central zone of the GC (+68% (+/− 17%)). In particular, the intracellular calcium rise was strongest within the CZ of the GC, a region that expresses an abundant amount of α7 and Gprin1 (Fig. 2). In filopodia, PNU treatment was also found to augment calcium levels by 24% (+/− 7%). The effect of PNU on intracellular calcium levels recovered to baseline at ~0.5 sec. consistent with data on α7 channel kinetics (Fayuk & Yakel 2004) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Detection an α7 calcium current in the growth cone. Cells were analyzed for intracellular calcium changes using Fluo-8AM. (a) Calcium detection in soma, axon, central zone, and filopodia of hippocampal neurons. Normalized traces were obtained from calcium reading in 10 cells (n=10) where 0.1% DMSO alone was used as a vehicle control. An empty pRNAT H1.1 vector was used as a transfection control for Gprin1-traces. Histograms showing relative changes in calcium peaks at time of drug treatment. (b–d) Drug induced calcium changes in the GC (white trace). Top row: before drug application; bottom row: after drug application. Central zone (CZ); PNU (10 µM); Bgtx (50 nM).

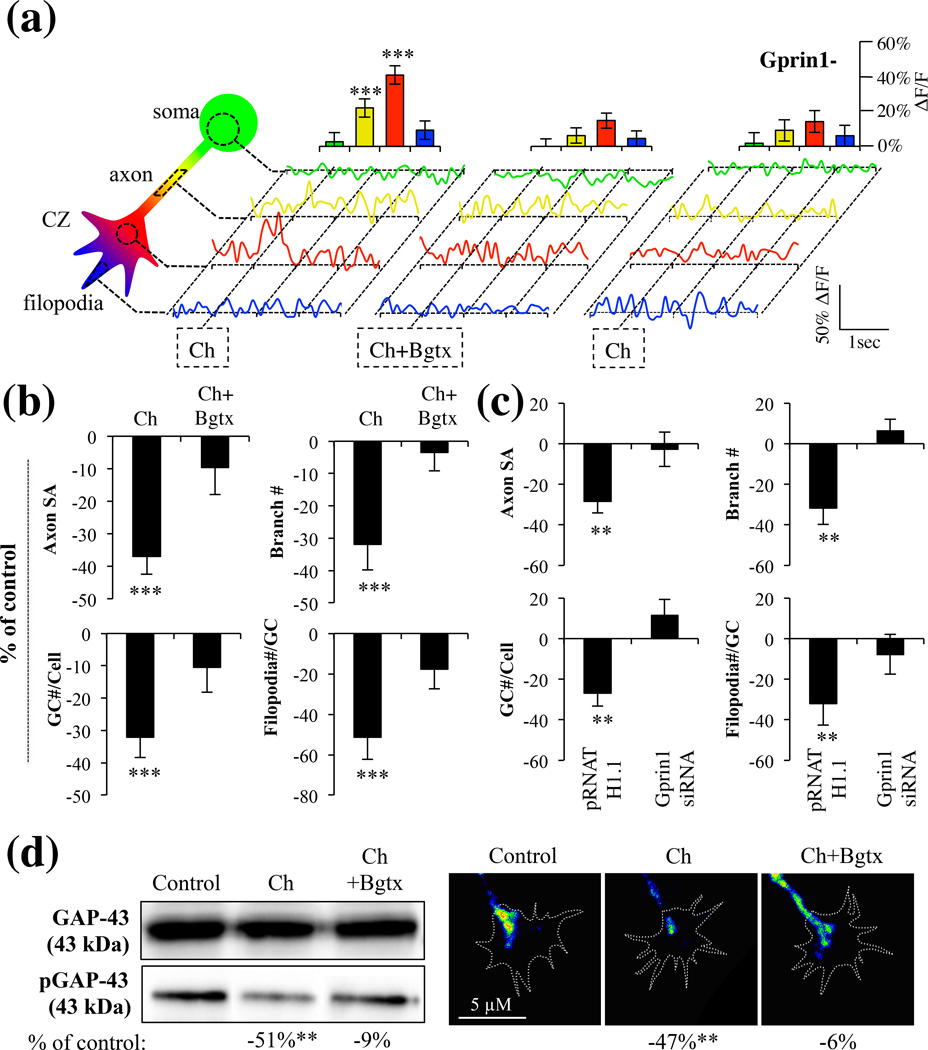

Choline can endogenously activate α7, thereby critically contributing to brain development (Khiroug et al. 2002). We confirmed the effects of α7 activation in hippocampal neurons using (1mM) choline, a concentration previously found to physiologically activate the receptor (Khiroug et al. 2002). We found that choline increased intracellular calcium levels but most significantly in the GC of the neuron (Fig. 7). The effect of choline was blocked by Bgtx underscoring the specificity of this transmitter for α7. Interestingly choline was found to have little to no effect on calcium levels in the soma (Fig. 7a). The findings suggest that the effects of choline on α7 may be altered by differential mechanisms of transmitter re-uptake in various neuronal compartments (Guermonprez et al. 2002). To confirm that choline and PNU produce similar effects on axon growth, an analysis of axon morphology and pGAP-43 levels was also determined in response to choline. Axon development, GC branching and pGAP-43 levels were all significantly attenuated by choline and this effect was also blocked by the addition of Bgtx (Fig. 7). Taken together, the findings indicate that α7 activation mediates intracellular calcium signaling leading to an inhibition in axon development.

Fig. 7.

Choline activation of α7 in the growth cone. Cells were analyzed for intracellular calcium changes using Fluo-8AM in response to Choline (Ch) treatment. Ch=1 mM; Bgtx=50 µM. (a) Calcium detection in soma, axon, central zone, and filopodia of hippocampal neurons. Traces were averaged from 7 cells (n=7). Histograms show the relative change in calcium of peaks at the time of drug treatment. Water was used as a vehicle control. (b) Morphometric analysis of growth in choline treated cells. The data is contiguous with analysis presented in Fig. 3 confirming the effect of α7 on axon growth. Water was used as a vehicle control. (c) Morphometric analysis in Gprin1- cells treated with choline. The data is contiguous with analysis presented in Fig. 4 supporting the role of Gprin1 in α7-mediated inhibition of growth. Values are based on average percent change in axon growth from control cells (cells transfected with the same plasmid but treated with 0.1% DMSO). (d) Detection of GAP-43 and pGAP-43 in neurons following 60 min treatment with choline or choline and Bgtx. Changes in pGAP-43 expression were detected in the GC. Water was used as a vehicle control.

To confirm the contribution of Gprin1 in α7 mediated calcium entry into the growing hippocampal neurons, Gprin1- cells were analyzed for the effect of PNU (Fig. 6) and choline (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 6, knockdown of Gprin1 expression is associated with a significant reduction in the cell’s calcium responsiveness to PNU treatment (−19% (+/− 9%) in the soma; −25% (+/− 11%) in the axon, and −53% (+/− 8%) in the CZ) relative to an empty plasmid (pRNAT H1.1) control. Similar data was obtained with choline treatment (Fig. 7), confirming the role of Gprin1 in α7 mediated calcium signaling in the developing axon. The findings also present a first ever demonstration of an α7 calcium signal in the GC, and suggest that this cholinergic signal contributes to the maturation of the axon.

Discussion

A new role for α7 in axon growth

In this study we define an interaction between α7 and Gprin1 and demonstrate that this interaction regulates axon growth in hippocampal neurons. We present evidence on the localization and signaling of α7 in GCs as supported by histochemical and western blot detection of the receptor and its interacting protein Gprin1 in developing hippocampal neurons. By interacting with Gprin1, the localization of α7 in the GC appears to enable cholinergic signals to direct the growth of the axon. Based on this evidence, the interaction of the two proteins and their coupling to a downstream G protein-signaling pathway is proposed to contribute to brain development.

Interestingly, while this study demonstrates a role for α7 in axon development, earlier work has shown that knockdown of the α7 can decrease dendritic length and branching in newborn neurons of the dentate gyrus (Campbell et al. 2010, Liu et al. 2010). This suggests that α7 may differentially contribute to axon and dendrite development by interacting with scaffolding proteins such as Gprin1, which can guide the expression and mediate the function of the receptor in specific neuronal compartment. In this regard, the function of Gprin1 in localizing α7 activity in the developing axon, may be paralleled by another, still unknown, protein that can direct the receptor to dendrites (Campbell et al. 2010). In future studies, it will be important to examine the proteomic interactions of α7 in maturing dendrites.

Activation of α7 causes local calcium elevation and a collapse of the GC

The synaptic localization and high calcium permeability of α7 enables it to influence diverse events, ranging from modulation of transmitter release to synaptic plasticity (McGehee et al. 1995, Gu & Yakel 2011). The expression and function of α7 in the GC during axon maturation appears dependent on interaction with Gprin1, which directs the trafficking of the receptor to the cell surface and the central zone. This positions α7 at sites where developmental demands are high, and enables it to influence cytoskeletal mechanisms of growth (Lowery & Van Vactor 2009). As a consequence, α7 mediated elevations in intracellular calcium can arrest axon growth as shown previously for other calcium channels (Kater & Mills 1991, Henley & Poo 2004). The α7 mediated calcium rise in the GC communicates a “stop” signal for the growing axon, which is made possible by association with Gprin1 and modulation of the Gαo, GAP-43, and CDC42 pathway (Nakata & Kozasa 2005, Frey et al. 2000). This hypothesis is supported by our observation that activation by α7 (by PNU or choline) promotes dephosphorylation of GAP-43, GTP hydrolysis of CDC42, and negatively influences EB3 microtubule comet velocity in the GC leading to its collapse. Mechanistically this may be achieved via α7-mediated calcium elevations into the GC which can inactivate GAP-43 via calcium sensitive proteins such as calpain (Zakharov & Mosevitsky 2007) and PP2B (Lyons et al. 1994), leading to inhibition of Gα fo and CDC42 in the axon (Bromberg et al. 2008a). It is interesting to consider the possible effects of α7 on other downstream Rho-GTPases involved in growth. RhoA has previously been shown to inhibit axon growth and GC collapse while Gαo can regulate of RhoA activity (Bromberg et al. 2008a). Thus the ability of α7 to inhibit axon growth may involve the regulation of other possible RhoGTPases through interaction with the GPC. In the long-term, activation of α7 is associated with a dramatic reduction in axon length and branching complexity.

A functional α7 signal in the growing axon can play an important role in early-life synaptic development (Luo & O'Leary 2005). Defects in processes such as neurogenesis and axon pruning can lead to pernicious axon growth implicated in a number of developmental brain disorders such as autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia (Saugstad 2011, Zhou et al. 2012). Recent findings linking the expression of the α7 gene CHRNA7 to developmental disorders (Yasui et al. 2011, Adams et al. 2012), supports the role of this receptor in proper brain development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Wings for Life Spinal Cord Research Foundation Grant to NK and an R01-HL104127 grant to CDN.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams CE, Yonchek JC, Schulz KM, Graw SL, Stitzel J, Teschke PU, Stevens KE. Reduced Chrna7 expression in mice is associated with decreases in hippocampal markers of inhibitory function: implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Neuroscience. 2012;207:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Bonfante-Cabarcas R, Marchioro M, Matsubayashi H, Alkondon M, Maelicke A. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on hippocampal neurons: cell compartment-specific expression and modulatory control of channel activity. Prog Brain Res. 1996;109:111–124. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Braga MF, Matsubayashi H, Alkondon M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors modulate synaptic function in the hippocampus and are sensitive to blockade by the convulsant strychnine and by the anti-Parkinson drug amantadine. Toxicol Lett. 1998;102–103:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg KD, Iyengar R, He JC. Regulation of neurite outgrowth by G(i/o) signaling pathways. Front Biosci. 2008a;13:4544–4557. doi: 10.2741/3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg KD, Ma'ayan A, Neves SR, Iyengar R. Design logic of a cannabinoid receptor signaling network that triggers neurite outgrowth. Science. 2008b;320:903–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1152662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel-Jungerman E, Lucassen PJ, Francis F. Cholinergic influences on cortical development and adult neurogenesis. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NR, Fernandes CC, Halff AW, Berg DK. Endogenous signaling through alpha7-containing nicotinic receptors promotes maturation and integration of adult-born neurons in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8734–8744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0931-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Quik M. A role for the nicotinic alpha-bungarotoxin receptor in neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Neuroscience. 1993;56:441–451. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90344-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LT, Gilman AG, Kozasa T. A candidate target for G protein action in brain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26931–26938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronas V, Durand M, Chabot JG, Jourdan F, Quirion R. Acetylcholine induces neuritic outgrowth in rat primary olfactory bulb cultures. Neuroscience. 2000;98:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luca A, Vassallo S, Benitez-Temino B, Menichetti G, Rossi F, Buffo A. Distinct modes of neuritic growth in purkinje neurons at different developmental stages: axonal morphogenesis and cellular regulatory mechanisms. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Hayes JA, Rekling JC. Dendritic calcium activity precedes inspiratory bursts in preBotzinger complex neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1017–1022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4731-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Meiri KF. Distribution of phosphorylated GAP-43 (neuromodulin) in growth cones directly reflects growth cone behavior. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:287–299. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980605)35:3<287::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Kouhen R, Hu M, Anderson DJ, Li J, Gopalakrishnan M. Pharmacology of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase signalling in PC12 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbediwy A, Zihni C, Terry SJ, Clark P, Matter K, Balda MS. Epithelial junction formation requires confinement of Cdc42 activity by a novel SH3BP1 complex. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:677–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsas SM, Kwak EM, Stent GS. Acetylcholine-induced retraction of an identified axon in the developing leech embryo. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1419–1436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01419.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine L, McCaig CD. Growth cone neurotransmitter receptor activation modulates electric field-guided nerve growth. Dev Biol. 1995;171:330–339. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayuk D, Yakel JL. Regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel function by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in rat hippocampal CA1 interneurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:658–666. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Liu DM, Lee A, Harries JC, Adams DJ. Selective modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel subunits by Goprotein subunits. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3571–3577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4971-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey D, Laux T, Xu L, Schneider C, Caroni P. Shared and unique roles of CAP23 and GAP43 in actin regulation, neurite outgrowth, and anatomical plasticity. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1443–1454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Qiu Y, Loh HH, Law PY. GRIN1 regulates micro-opioid receptor activities by tethering the receptor and G protein in the lipid raft. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36521–36534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Yakel JL. Timing-dependent septal cholinergic induction of dynamic hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2011;71:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermonprez L, O'Regan S, Meunier FM, Morot-Gaudry-Talarmain Y. The neuronal choline transporter CHT1 is regulated by immunosuppressor-sensitive pathways. J Neurochem. 2002;82:874–884. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan MA, Kabbani N, Paspalas CD, Levenson R. Interaction with dopamine D2 receptor enhances expression of transient receptor potential channel 1 at the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:974–982. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JA, Wang X, Del Negro CA. Cumulative lesioning of respiratory interneurons disrupts and precludes motor rhythms in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8286–8291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200912109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Francis F, Myers KA, Yu W, Black MM, Baas PW. Role of cytoplasmic dynein in the axonal transport of microtubules and neurofilaments. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;168:697–703. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley J, Poo MM. Guiding neuronal growth cones using Ca2+ signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CK, Byun N, Bubser M. Muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists and allosteric modulators for the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:16–42. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J, Galindo MF, Prehn JH, Weichselbaum RR, Beckett M, Ghadge GD, Roos RP, Leiden JM, Miller RJ. p53 expression induces apoptosis in hippocampal pyramidal neuron cultures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1397–1405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N. Intracellular complexes of the beta2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in brain identified by proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710314104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N, Negyessy L, Lin R, Goldman-Rakic P, Levenson R. Interaction with neuronal calcium sensor NCS-1 mediates desensitization of the D2 dopamine receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8476–8486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08476.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N, Woll MP, Levenson R, Lindstrom JM, Changeux JP. Intracellular complexes of the beta2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in brain identified by proteomics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20570–20575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710314104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Akerboom T, Molnar P, Reinauer H. Modified HPLC-electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry method for HbA1c based on IFCC reference measurement procedure. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1018–1022. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.100875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater SB, Mills LR. Regulation of growth cone behavior by calcium. J Neurosci. 1991;11:891–899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00891.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khiroug SS, Harkness PC, Lamb PW, Sudweeks SN, Khiroug L, Millar NS, Yakel JL. Rat nicotinic ACh receptor alpha7 and beta2 subunits coassemble to form functional heteromeric nicotinic receptor channels. J Physiol. 2002;540:425–434. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma R, Sarner S, Ahmed S, Lim L. Rho family GTPases and neuronal growth cone remodelling: relationship between increased complexity induced by Cdc42Hs, Rac1, and acetylcholine and collapse induced by RhoA and lysophosphatidic acid. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1201–1211. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu B, Koch E, Schmidt JT. GAP43 phosphorylation is critical for growth and branching of retinotectal arbors in zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:897–911. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J, Schoepfer R, Conroy WG, Whiting P. Structural and functional heterogeneity of nicotinic receptors. Ciba Found Symp. 1990;152:23–42. doi: 10.1002/9780470513965.ch3. discussion 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Nadar VC, Kozielski F, Kozlowska M, Yu W, Baas PW. Kinesin-12, a mitotic microtubule-associated motor protein, impacts axonal growth, navigation, and branching. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14896–14906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3739-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Neff RA, Berg DK. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science. 2006;314:1610–1613. doi: 10.1126/science.1134246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse K, Helmke SM, Wood MR, Quiroga S, de la Houssaye BA, Miller VE, Negre-Aminou P, Pfenninger KH. Axonal origin and purity of growth cones isolated from fetal rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;96:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery LA, Van Vactor D. The trip of the tip: understanding the growth cone machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:332–343. doi: 10.1038/nrm2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozada AF, Wang X, Gounko NV, Massey KA, Duan J, Liu Z, Berg DK. Glutamatergic synapse formation is promoted by alpha7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7651–7661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6246-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, O'Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons WE, George EB, Dawson TM, Steiner JP, Snyder SH. Immunosuppressant FK506 promotes neurite outgrowth in cultures of PC12 cells and sensory ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3191–3195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myatt DR, Nasuto SJ. Improved automatic midline tracing of neurites with Neuromantic. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl I) [Google Scholar]

- Nadar VC, Ketschek A, Myers KA, Gallo G, Baas PW. Kinesin-5 is essential for growth-cone turning. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1972–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata H, Kozasa T. Functional characterization of Galphao signaling through G protein-regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:695–702. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordman JC, Kabbani N. An alpha7 nicotinic receptor-G protein pathway complex regulates neurite growth in neural cells. J Cell Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.110379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. Primary Culture of Hippocampal Neurons from P0 Newborn Rats. J Vis Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulo JA, Brucker WJ, Hawrot E. Proteomic analysis of an alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor interactome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1849–1858. doi: 10.1021/pr800731z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccomagno MM, Hurtado A, Wang H, Macopson JG, Griner EM, Betz A, Brose N, Kazanietz MG, Kolodkin AL. The RacGAP beta2-Chimaerin selectively mediates axonal pruning in the hippocampus. Cell. 2012;149:1594–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudiger T, Bolz J. Acetylcholine influences growth cone motility and morphology of developing thalamic axons. Cell Adh Migr. 2008;2:30–37. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.1.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad LF. Infantile autism: a chronic psychosis since infancy due to synaptic pruning of the supplementary motor area. Nutr Health. 2011;20:171–182. doi: 10.1177/026010601102000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova T, Slemmer J, Hoogenraad CC, et al. Visualization of microtubule growth in cultured neurons via the use of EB3-GFP (end-binding protein 3-green fluorescent protein) J Neurosci. 2003;23:2655–2664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter SM, Fishman MC, Zhu XP. Activated mutants of the alpha subunit of G(o) promote an increased number of neurites per cell. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2327–2338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02327.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarzenski BC, O'Malley KL, Todd RD. PTX-sensitive regulation of neurite outgrowth by the dopamine D3 receptor. Neuroreport. 1996;7:573–576. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui DH, Scoles HA, Horike S, Meguro-Horike M, Dunaway KW, Schroeder DI, Lasalle JM. 15q11.2-13.3 chromatin analysis reveals epigenetic regulation of CHRNA7 with deficiencies in Rett and autism brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4311–4323. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov VV, Mosevitsky MI. M-calpain-mediated cleavage of GAP-43 near Ser41 is negatively regulated by protein kinase C, calmodulin and calpain-inhibiting fragment GAP-43-3. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1539–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JQ, Poo MM. Calcium signaling in neuronal motility. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YD, Zhang D, Ozkaynak E, Wang X, Kasper EM, Leguern E, Baulac S, Anderson MP. Epilepsy gene LGI1 regulates postnatal developmental remodeling of retinogeniculate synapses. J Neurosci. 2012;32:903–910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5191-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.