Abstract

The relationship between renal salt handling and hypertension is intertwined historically. The discovery of WNK kinases (With No lysine = K) now offers new insight to this relationship because WNKs are a crucial molecular pathway connecting hormones such as angiotensin II and aldosterone to renal sodium and potassium transport. To fulfill this task, the WNKs also interact with other important kinases, including serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1, STE20/SPS1-related, proline alanine-rich kinase, and oxidative stress responsive protein type 1. Collectively, this kinase network regulates the activity of the major sodium and potassium transporters in the distal nephron, including thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporters and ROMK channels. Here we show how the WNKs modulate ion transport through two distinct regulatory pathways, trafficking and phosphorylation, and discuss the physiologic and clinical relevance of the WNKs in the kidney. This ranges from rare mutations in WNKs causing familial hyperkalemic hypertension to acquired forms of hypertension caused by salt sensitivity or diabetes mellitus. Although many questions remain unanswered, the WNKs hold promise for unraveling the link between salt and hypertension, potentially leading to more effective interventions to prevent cardiorenal damage.

In the last 10 years, a number of previously unrecognized kinases interacting in the distal nephron have been identified as playing important roles in sodium, potassium, and BP regulation. Among these are the WNKs (with no lysine = K), serine threonine kinases, which are atypical because the catalytic lysine crucial for binding to ATP is located in subdomain I instead of II. The WNK kinases were identified while searching for novel members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase family.1 The finding that mutations in WNK kinases cause the monogenetic disorder, familial hyperkalemic hypertension (FHHt, also known as pseudohypoaldosteronism type II or Gordon syndrome),2 sparked further interest in these regulatory proteins.3 Subsequent studies implicate WNK kinases in the direct or indirect regulation of the major sodium and potassium transporters in the distal nephron and in the pathogenesis of hypertension.

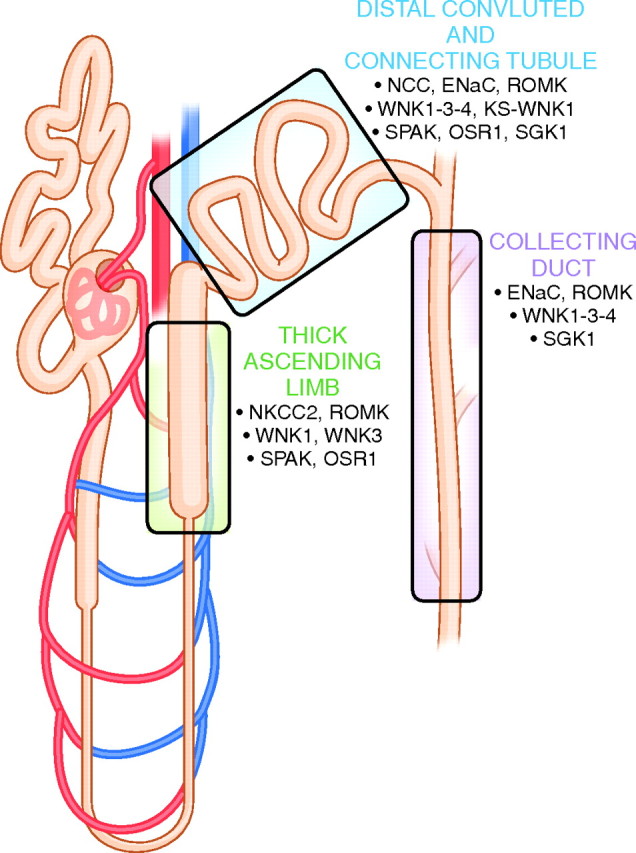

Based on the disease phenotype resulting from WNK kinase mutations, it is clear that WNKs play important roles in regulating ion channels and transporters. There is now abundant evidence, both in vitro and in vivo, that WNK kinases regulate the renal outer medullary potassium channel (ROMK),4 the sodium potassium chloride cotransporter type 2 (NKCC2),5 the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC),6 and the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) (Figure 1).7 WNK kinases modulate many other transport proteins as well.8.

Figure 1.

Expression of major sodium and potassium transport proteins in the distal nephron, including WNK kinases and associated regulatory proteins. See text for abbreviations.

Four WNK kinases are expressed in the kidney, WNK1, kidney-specific WNK1 (KS-WNK1), WNK3, and WNK4, where they are most abundant along the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron; this segment comprises the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), connecting tubule (CNT), and collecting duct (CD) (Figure 1).9 The protein structure of WNKs consists of a kinase domain, an autoinhibitory domain, an autophosphorylation site, coiled-coil domains, and proline-rich sequences.8 WNK kinases affect solute transporters by discrete, but probably related actions, which include modulating trafficking of proteins to or from the plasma membrane and modulating transport protein phosphorylation. Although effects mediated by phosphorylation events are important, most require intermediary kinases. Intermediary kinases include STE20/SPS1-related, proline alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress responsive protein type 1 (OSR1),10,11 two highly homologous kinases that are phosphorylated and activated by WNK kinases. SPAK and OSR1 act in the thick ascending limb (TAL) and DCT, where they phosphorylate NKCC2 and NCC (Figure 1).10,11 Additionally, WNKs interact with serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1).12 SGK1 is an important kinase for the transduction of aldosterone's effect and therefore acts in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (Figure 1).13

We will first review briefly what is known about mechanisms by which WNKs regulate NaCl and K+ transport. Second, we will review the physiologic and clinical relevance of renal WNKs and hypertension (Table 1). The focus of this review, therefore, is on the WNKs in the kidney, but it is important to emphasize that WNK kinases are not only expressed in the kidney, but also in brain, heart, lung, bone, testis, and the gastrointestinal tract. In these organs, a role for WNK kinases has been implicated for diseases as diverse as neuropathy, autism, cancer, and osteoporosis.8

Table 1.

Potential clinical relevance of WNK kinases in nephrology

| Mutations in WNK1 or WNK4 cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension |

| Salt retention caused by aldosterone or angiotensin II is mediated via WNK kinases |

| Polymorphisms in the WNK1 and WNK4 genes are associated with hypertension |

| A low potassium diet may predispose to hypertension because it increases the WNK1/KS-WNK1 ratio leading to more salt reabsorption |

| WNK4 mediates the antinatriuretic effects of insulin in diabetes mellitus |

| The WNKs are promising candidates for development of new anti-hypertensive drugs |

WNK KINASES: TRAFFICKING AND PHOSPHORYLATION

As stated eloquently by Bradbury and Bridges,14 “membrane transport falls into two fundamental categories: alteration in transport activities (i.e., transporter kinetics) of membrane resident proteins or alterations in the number of transport proteins per unit area.” The second category can again be divided into de novo synthesis of transport proteins, occurring in hours, and the rapid recruitment of preformed transporters residing in intracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane, occurring in minutes. The latter is often referred to as trafficking and constitutes a dynamic recycling process of endocytic retrieval and plasma membrane insertion of transport proteins. Phosphorylation, on the other hand, is one of the most important post-translational modifications that can activate or deactivate proteins through conformational changes. Because WNKs are kinases, it is not surprising that they modulate transporter function by affecting phosphorylation. It is unclear, however, if WNK kinases are capable of phosphorylating transporters directly.15,16 Instead, there is evidence that WNK1, WNK3, and WNK4 phosphorylate SPAK and OSR1, which in turn phosphorylate and activate NKCC2 and NCC.10,17–20 Both trafficking and phosphorylation are influenced by hormones to meet the requirements of the body and restore homeostasis. Although trafficking and phosphorylation are distinct and unique regulatory modalities, they are probably closely related under most physiologic conditions. At present, it is unknown whether WNK-regulated transport proteins are phosphorylated in the cytoplasm, thereby signaling movement to and insertion into the plasma membrane, or whether phosporylation takes place once the protein is located in the plasma membrane. We will examine the roles of trafficking and phoshorylation in the regulation of NKCC2, NCC, and ROMK. WNKs also seem to contribute to the regulation of ENaC primarily through SGK1,7,21 but the data are limited, and this subject is therefore not covered here.22

Regulation of the NCC

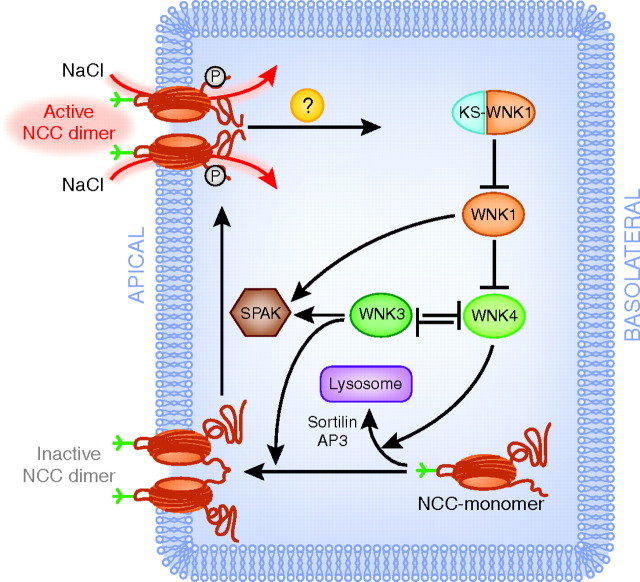

A great deal of attention has been focused on WNK regulation of NCC, because the clinical phenotype of FHHt is thiazide-sensitive. As shown in Figure 2, WNK4 is believed to inhibit NCC activity by reducing its plasma membrane abundance6; several investigators have also observed that WNK4 reduces the steady-state abundance of NCC.23 WNK4 does not seem to interfere with the endocytic retrieval of NCC, because studies in mammalian cells show that plasma membrane abundance of NCC is unaffected by wild-type or mutant dynamin, a GTPase responsible for clathrin-mediated endocytosis.24,25 Rather, WNK4 seems to affect the forward trafficking pathway by diverting post-Golgi NCC to lysosomal degradation, thereby preventing delivery to the plasma membrane (Figure 2).23 This concept was derived from cell studies in which brefeldin A was used to inhibit forward trafficking of NCC to the plasma membrane; brefeldin A was then washed out, and WNK4 was shown to reduce the rate of NCC recovery at the plasma membrane.26 Another protein involved in causing this detour of NCC to the lysosomes is sortilin, a receptor in the Golgi complex that helps routing of proteins to lysosomes.27 Further evidence for the WNK4-induced degradation of NCC in lysosomes was obtained by showing the reversal of this process by bafilomycin A1, which disturbs lysosomal function by inhibiting the vacuolar H+-ATPase.24

Figure 2.

Model of NCC regulation by WNK kinases. NCC is trafficked as a monomer from the cytosol to the apical plasma membrane to become an inactive dimer (lower half of figure). Activation of the NCC dimer is achieved by phosphorylation through SPAK, stimulating NaCl transport (left). This process is regulated by WNK kinases. WNK4 (green symbol) inhibits the trafficking step of NCC by diverting it to the lysosome, a process that is mediated by sortilin and adaptin 3 (AP3). Conversely, WNK3 (red symbol) stimulates trafficking. WNK3 and WNK4 inhibit each other's activities. WNK4 is inhibited by WNK1 (red symbol), which in turn is inhibited by KS-WNK1 (blue and red symbol). WNK1 and WNK3 are also thought to influence the activity of SPAK, thereby controlling the phosphorylation and thus activation step of NCC. At present, it is unknown how the endocytic retrieval of NCC is regulated (question mark symbol). See text for details and abbreviations.

There is less information about how other WNK kinases affect protein trafficking. In contrast with an initial model that postulated that WNK1 modulates NCC only through WNK4, recent evidence suggested that WNK1 regulates trafficking by facilitating the final steps of NCC insertion into the plasma membrane by interacting with the SNARE protein STX-3.28 The exact role of WNK3 in NCC regulation remains elusive, but oocyte and cell studies showed that WNK3 is a positive regulator of NCC and that the net effect on NCC is determined by antagonism between WNK3 and WNK4.5,15 When expressed in Xenopus oocytes, the effects of WNK3 to increase NCC activity can be dissociated from effects on phosphorylation.29

Besides trafficking, NCC is regulated by phosphorylation. A number of recent studies showed that both plasma membrane abundance and phosphorylation of NCC are increased by aldosterone,30–32 angiotensin II,30,32,33 and, surprisingly, vasopressin.34,35 SGK1, WNKs, and/or SPAK are identified as the main intracellular mediators of these receptor–transporter cascades.30–33,35 Although phosphorylation and trafficking can be dissociated in vitro, it remains to be determined whether trafficking and phosphorylation can occur independently in vivo and what their relative contributions are in the regulation of NCC.

Regulation of the NKCC2

NKCC2, the major sodium transporter in the TAL, is an interesting example of how trafficking and phosphorylation act in concert to regulate transporter activity. Using Xenopus oocytes, Giménez and Forbush36 showed that, under isotonic and hypotonic conditions, NKCC2 retained 50% of its activity in the absence of phosphorylation of three important threonines (99, 104, 117 in the rabbit sequence). Phosphorylation of these three residues, however, was necessary to stimulate NKCC2 activity during hypertonicity. Also in oocytes, Ponce-Coria et al.18 found that the activation of NKCC2 by low intracellular chloride also required phosphorylation of the three highly conserved threonines. In addition, they found that phosphorylation of NKCC2 also requires an interaction between WKN3 and SPAK, because elimination of WNK3's SPAK-binding motif, or catalytically inactive WNK3, prevents the activation of NKCC2. Based on these data, the investigators postulated WNK3 to be a chloride sensor. Recently, it was shown that NKCC2 phosphorylation also requires proper trafficking of SPAK by a trafficking protein called sorting protein-related receptor with A-type repeats (SORLA).37 SORLA is expressed in the TAL, and SORLA-deficient mice exhibit missorting of SPAK and an inability to phosphorylate NKCC2. The mice had a mild Bartter-like phenotype with lower BP, higher aldosterone, kaliuresis, and calciuresis, and an inability to conserve sodium during water deprivation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of phenotypes of genetically modified mouse models targeting WNK kinases or associated proteins

| Mouse Model | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Salt-sensitive hypotensive models | ||

| NKCC2−/− (indomethacin rescued) | Bartter-like | 54 |

| SORLA−/− | Bartter-like | 37 |

| NCC−/− | Gitelman-like | 56 |

| transgenic (WNK4WT) | Gitelman-like | 63 |

| “hypomorphic” WNK4 | Gitelman-like | 64 |

| SPAK−/− | Gitelman-like | 66 |

| SPAK243A/243A (kinase-dead knockin) | Gitelman-like | 67 |

| SGK−/− | Salt-sensitive hypotension, hyperkalemia | 60 |

| Salt-sensitive hypertensive models | ||

| transgenic (WNK4PHAII) | FHHt-like | 63 |

| WNK4D561A/+ (knockin) | FHHt-like | 70 |

| No phenotype | ||

| transgenic (NCC) | No phenotype | 71 |

| KS-WNK1−/− | No phenotype | 73 |

| collecting duct–specific ENaC−/− | No phenotype | 59 |

See text for abbreviations of protein names and explanations of the phenotypes. FHHt, familial hyperkalemic hypertension.

Regulation of the ROMK

WNK kinases also modulate ROMK by affecting clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The proof for this mainly comes from a study in mammalian cells by He et al.,38 showing that WNK1 and WNK4 interact with the endocytic scaffold protein intersectin. They showed that the proline-rich motifs of WNK1 and WNK4 bind to the SH3 domains of intersectin. This allows the formation of a complex consisting of ROMK interacting with WNK4 and WNK1–WNK4 interacting with intersectin.39 Intersectin is a crucial protein in orchestrating endocytosis by recruiting dynamin and synaptojanin, eventually leading to endocytosis in clathrin-coated vesicles. Recently, it was shown that the recruitment of ROMK to clathrin-coated vesicles is mediated by a protein called clathrin adaptor molecule in autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH).40 Functional data to support a role for ARH in ROMK and potassium regulation include an inverse correlation between ARH and ROMK expression during potassium depletion and the inability of ARH-deficient mice to downregulate ROMK during potassium depletion.40

PHYSIOLOGIC RELEVANCE

The Aldosterone Paradox

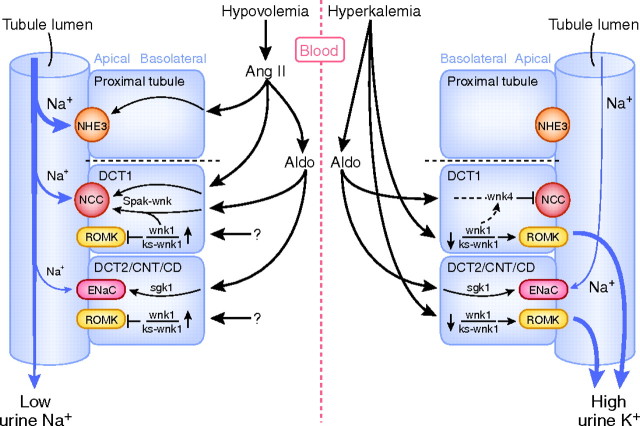

Contraction of the extracellular fluid volume is a threat to survival, and as a consequence, mammalian kidneys conserve sodium avidly. Hyperkalemia is equally threatening, and as a consequence, kidneys can secrete potassium rapidly. The ability of kidneys to conserve sodium and excrete potassium may reflect dietary composition in Paleolithic times; during that period, diets were sodium deplete but potassium replete.41,42 Aldosterone plays a central role in renal control of both sodium chloride reabsorption and potassium secretion. Indeed, major renal sodium and potassium transporters are regulated by aldosterone, including NCC,43 ENaC,44 and ROMK.45,46 However, the challenges of volume depletion and potassium overload are often dissociated, and aldosterone secretion is stimulated by either angiotensin II (in states of extracellular fluid volume depletion) or serum K+ concentration (in states of K+ excess; Figure 3). When aldosterone is secreted in response to angiotensin II, its primary effect is NaCl retentive; when it is stimulated in response to hyperkalemia, its primary effect is kaliuretic.47 The observation that aldosterone can serve distinct functions, depending on the secretory stimulus, has been termed the aldosterone paradox.42 Explanations hinge on the balance between NaCl transport and Na+/K+ exchange, but until recently, mechanisms have remained elusive.

Figure 3.

Model of the “aldosterone paradox.” Two pathophysiological settings are depicted: hypovolemia (left) and hyperkalemia (right). Aldosterone acts as a sodium retaining hormone during hypovolemia, leading to a low urinary Na+ excretion (left). Conversely, aldosterone acts as a K+-secreting hormone during hyperkalemia, leading to a high urinary K+ excretion (right). Hypovolemia stimulates angiotensin II (Ang II), which in turn increases aldosterone (Aldo). Both contribute to renal Na+ retention. Ang II stimulates Na+ transport in the proximal tubule by activating the NHE3. Ang II also increases the activity of the NCC in the early DCT1. Aldo activates both NCC and the ENaC in the late DCT (DCT2), CNT, and CD. Note that because Na+ transport is stimulated at three locations, the distal delivery of Na+ decreases, contributing to the low Na+ excretion. The effects of Ang II and Aldo are primarily mediated via a WNK–SPAK pathway, whereas the effects of Aldo on ENaC primarily involves SGK1. Unknown factors increase the WNK1–KS–WNK1 ratio, leading to inhibition of the ROMK, helping to conserve potassium during hypovolemia. In the setting of hyperkalemia, the opposite occurs, because direct effects of a high serum K+ level decrease the WNK1–KS-WNK1 ratio (right). This leads to an activation of ROMK, stimulating potassium secretion. The lower WNK1–KS-WNK1 ratio also increases WNK4, preventing Aldo from activating NCC (dashed line). However, Aldo is still capable of activating ENaC, which stimulates Na+ exchange for K+ in the collecting duct.

There are likely to be several factors involved in mediating the discrepant effects of aldosterone. As shown in Figure 3, angiotensin II, in the presence of aldosterone, shifts the balance of Na+ reabsorption proximally. This proximal shift favors NaCl reabsorption. In contrast, aldosterone secretion in a setting of low angiotensin II (as in hyperkalemia) shifts Na+ reabsorption distally, favoring K+ secretion. Many factors contribute to these effects, but the WNK kinase network seems to play a role, acting as a molecular switch in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (Figure 3).48 The evidence for a switching effect includes the observation that FHHt is a disease in which the ability to dissociate the kaliuretic from the NaCl retentive effects is lost.49,50 This model, suggesting that WNK regulation participates in determining the nature of aldosterone action, is also supported by the observation that dietary K+ intake has substantial effects on WNK kinase abundance. Both the KS-WNK1/WNK1 ratio and the abundance of WNK4 increase on high potassium diets (hyperkalemia), but not on a low sodium diet (hypovolemia).51,52 According to the current model, the increase in KS-WNK1 and WNK4 would favor electrogenic transport with potassium secretion (Figure 3).53 The WNK kinase network is also modulated by angiotensin II, which is elevated when aldosterone secretion is stimulated by hypovolemia but not when it is stimulated by hyperkalemia. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence that angiotensin II, through WNK4 and SPAK, activates NCC, favoring NaCl reabsorption during hypovolemia.32,33

Lessons from Animal Models

Although in vitro studies help unravel regulatory mechanisms, animal models, coupled with phenotypic analysis of human disease, provide physiologic context. Many lessons have been learned from the development of animals in which either the transport proteins themselves, or the novel regulatory factors, have been modified genetically (Table 2). We will discuss those genotypes that result in renal sodium loss and hypotension (salt-sensitive hypotension); the salt-sensitive hypertensive models are discussed in the next section. Although it is not the focus of this review, it is useful first to discuss animal models in which distal sodium transporters are deleted, because they provide comparison with effects of regulatory protein modification. These knockout animals typically resemble human diseases in which the human homologs of the transport proteins are defective. NKCC2 dysfunction in humans is one cause of Bartter syndrome; NKCC2 knockout mice die of dehydration before weaning, unless rescued by indomethacin, in which case they exhibit a Bartter-like phenotype, with salt wasting, hypokalemia, and hypercalciuria.54 NCC dysfunction in humans causes Gitelman syndrome, with hypokalemic alkalosis, hypocalciuria, and magnesium wasting; NCC knockout animals exhibit a milder phenotype with hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria, but no other electrolyte or BP abnormalities when consuming a normal diet.55,56 When challenged with a low salt diet, however, BP declines more in the NCC-null animals than in wild type56; when challenged with a potassium-deficient diet, hypokalemia ensues.57 ENaC dysfunction also causes pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 in humans with profound neonatal salt wasting58; ENaC deletion causes a similar syndrome in animals when rescued from perinatal death, although ENaC deletion from the collecting duct alone does not cause a substantial phenotype, even when challenged with salt restriction, water deprivation, or potassium loading.59

The transporter-knockout models discussed above provide comparative information to analyze effects of regulatory proteins. Several mouse models have been generated in which proteins known to regulate NCC have been modified genetically, including WNK4, SPAK, and SGK1 (Table 2). SGK1-null mice do not recapitulate the effects of ENaC deletion but do exhibit hyperaldosteronism, mild hyperkalemia, and salt-sensitive hypotension because of reduced ENaC activity.60 Under baseline conditions, NCC abundance is normal, but when stressed with a low salt diet, NCC does not increase as much in SGK1 knockout as in wild type,61,62 providing evidence for an effect of SGK1 on NCC in vivo.

Animals transgenic for wild-type WNK4 exhibit reduced abundance of NCC. The BP and urinary calcium excretion are low, compared with wild-type animals, and they have hypokalemia on low potassium diets,63 providing evidence that WNK4 exerts an inhibitory effect on NCC in vivo. Animals in which WNK4 has been deleted have not been reported, because it has been suggested that WNK4 deletion may be embryonic lethal.64 Instead, Ohta et al.64 generated WNK4 hypomorphic animals, by deleting one exon of the WNK4 gene outside the kinase domain. The animals exhibit salt-sensitive hypotension and a reduction in phosphorylated, but not total, NCC. SPAK and ROMK were unaltered, whereas the expression of all ENaC subunits was increased.64 The authors interpreted the results as indicating that wild-type WNK4 exhibits NCC-stimulating activity at baseline. This finding contrasts with the conclusions reached above, that WNK4 exhibits NCC-inhibiting activity.6,65 In view of the suggestion that it is the kinase activity of WNK4 that, through SPAK, stimulates NCC activity, it is unclear how deletion of a nonkinase WNK4 exon alters NCC activity; clearly, this is an area that requires further investigation.

The effects of SPAK in vivo have been analyzed using a knockout66 and knockin strategy, in which an essential T-loop threonine is mutated to alanine to prevent kinase activation.67 Resulting animals exhibit a Gitelman phenotype with reduced expression and phosphorylation of NCC.66,67 It is noteworthy that mice with absent or inactive SPAK but not NCC-null mice display a profoundly lower baseline BP.56,66,67 This suggests that SPAK's regulation of NCC is not the only mechanism by which SPAK regulates BP. Indeed, SPAK-null mice also have impaired vasoconstriction, likely because SPAK phosphorylates NKCC1 in vascular smooth muscle cells.66 Still unresolved, however, is how SPAK can differentially regulate NKCC2 and NCC and how different manipulations of SPAK can either result in a Bartter37 or a Gitelman phenotype.66,67

In summary, these in vivo studies showed that genetic inhibition of WNK4, SPAK, or SGK1 results in reduced NCC activity, leading to a reduced ability to retain sodium with hypotension, especially during salt depletion. The studies to date, however, are limited by the experimental approaches, leaving many questions unanswered.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Familial Hyperkalemic Hypertension

The most obvious clinical relevance of the WNK kinases is the insight in the molecular pathogenesis of FHHt. FHHt is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by hypertension, hyperkalemia, hypercalciuria, and metabolic acidosis, all of which can be corrected with thiazide diuretics.68 FHHt can occur by intronic deletions, causing overexpression of wild-type WNK1 or by missense mutations causing mutant WNK4. Although the mutations in WNK4 and WNK1 lead to largely (although perhaps not completely69) similar phenotypes, the mechanisms by which the mutations lead to disease may differ. Mice transgenic for genomic segments harboring mutant WNK4 faithfully recapitulate the FHHt phenotype described above (Table 2).63 The same is true for mutant WNK4 knockin mice in which increased total NCC, phosphorylation of NCC, SPAK, and OSR1 are observed.70 These observations suggest that WNK4 mutations cause the phenotype primarily, if not exclusively, by stimulating NCC activity. In preliminary work, however, we observe that mice transgenic for NCC do not reproduce the FHHt phenotype, suggesting the involvement of additional factors.71

The model shown in Figure 2, derived largely from work in vitro, suggests that WNK1 mutations lead to FHHt by altering the KS-WNK1/WNK1 ratio, thereby affecting NCC. This led investigators to generate mice in which intron 1 of the WNK1 gene was deleted. Surprisingly, this deletion caused overexpression of both WNK1 and KS-WNK1 in the DCT and other renal segments, whereas KS-WNK1 was also overexpressed in other tissues.72 The phenotype of these mice has not been reported. The same group also generated KS-WNK1–null mice; these did show a two-fold increase in NCC expression, confirming that KS-WNK1 acts as a WNK kinase network inhibitor in vivo.73 However, neither systolic hypertension nor hyperkalemia was observed, again illustrating that additional effects are required for the development of the complete FHHt phenotype.73 Conversely, mice overexpressing the KS-WNK1 amino terminus display hypokalemia and increased ROMK abundance, as well as hypotension and a decrease in NCC abundance.74 These data provide strong support for the model, originally postulated by Subramanya et al.,75 that KS-WNK1 acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of WNK1 in vivo (Figure 2).

Essential Hypertension

The fact that hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular and renal disease is well established. The true challenge is solving the hypertension paradox—more uncontrolled disease despite improved therapy.76 One contributor to this paradox could be that our understanding of molecular pathways that convey susceptibility to hypertension still lags behind therapeutic options. Interestingly, the majority of the identified hypertension susceptibility genes all point toward a role for the kidney,77 which is consistent with Guyton's prediction.78 The WNKs are a promising new link to hypertension.65,79 Indeed, several population studies now identify single nucleotide polymorphisms and haploptypes in the WNK1 and WNK4 genes that are not only associated with BP variation80 but also with hypertension severity,81 salt sensitivity,82 thiazide sensitivity,83 and urine potassium excretion.84 Interestingly, the WNK1 and WNK4 single nucleotide polymorphisms with the strongest associations were either located in or near the sites of the FHHt mutations.84,85 Although the effects of variants in a single gene may be modest, one study showed that when variants in the genes for WNK1, α-adducin (a cytoskeleton protein that also influences Na+-K+-ATPase activity), and Nedd4–2 (which ubiquinates ENaC) were combined, a significant effect was found on renal salt handling, the BP response to saline and thiazides, and nocturnal systolic BP.86

Except for polymorphisms, it would also be of interest to know whether heterozygosity for WNK, SPAK, or SGK kinases determines susceptibility to hypertension. The reverse was recently shown in the Framingham Heart Study population, where heterozygous inactivating mutations in NKCC2, NCC, and ROMK protected against hypertension.87 Similarly, mice heterozygous for the WNK1 mutation show a marked reduction in BP without other apparent side effects.88 This latter finding makes the WNKs obvious candidates as drug targets, and several screening strategies are already making progress.89 Although the development of isoform-specific inhibitors may be a challenge, there is substantial evidence that the WNK substrate specificity is not uniform, despite highly homologous kinase domains.17

Hypertension in Diabetes Mellitus

Besides the effects of angiotensin II and aldosterone, the effect of insulin on sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule is also becoming clearer.90 Hyperinsulinemia is a prominent feature of insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. Insulin receptors are expressed in the proximal tubule, DCT, and CD.90 Song et al.91 showed that the rise in BP in rats on chronic insulin treatment is likely caused by enhanced sodium reabsorption by NCC and ENaC, because treatment with hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride results in increased natriuresis. Interestingly, insulin also reduces renal cortical WNK4 expression, which contributes to activation of NCC and ENaC.91 NCC, the β-subunit of ENaC, and Na+-K+-ATPase also upregulate in the obese Zucker rat, a model of insulin resistance and obesity.92 More recently, the obese Zucker rat was shown to be more sensitive to thiazides than their lean counterparts, with a greater natriuresis, kaliuresis, and drop in BP on thiazides.93 Reduced renal cortical expression of WNK4 was also observed in this model. In addition to the possible regulation of NCC by insulin through WNK4, SGK1 is an established mediator of the effect of insulin on ENaC.13 Surprisingly, downregulation of insulin receptors also causes salt retention and hypertension, possibly through reduced renal nitric oxide production.94 Therefore, the contribution of insulin-induced anti-natriuresis relative to other anti-natriuretic factors in diabetes, such as higher plasma aldosterone levels, remains to be determined.95 Nevertheless, it is an interesting example of how the WNK kinase pathway may also play a role in acquired forms of hypertension.

CONCLUSIONS

Insights derived from the discovery of WNK kinases and the elucidation of their renal effects represent a new paradigm for the molecular physiology of renal sodium, potassium, and BP regulation. Despite startling progress in understanding their roles, however, many questions remain, including the precise mechanisms by which they regulate protein trafficking and phosphorylation, the exact pathogenesis of FHHt, and the role of WNKs in the development of hypertension. The current models, such as that shown in Figure 2, must be placed in the perspective of the methods used to obtain the data, which have often relied on cell systems. Although important, these studies should be complemented with physiologic studies in whole animals and genetic epidemiologic approaches in humans to establish an integrated model of this complex kinase network in health and disease.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

E.J.H. is supported by an Erasmus MC Fellowship 2008 (internal grant) and a Kolff Junior Postdoctoral grant (Dutch Kidney Foundation KJPB 08.004). DHE is supported by NIH R01 DK51496, by the Department of Veterans Affairs (merit Review) and by the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Xu B, English JM, Wilsbacher JL, Stippec S, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH: WNK1, a novel mammalian serine/threonine protein kinase lacking the catalytic lysine in subdomain II. J Biol Chem 275: 16795–16801, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furgeson S, Linas S: Mechanisms of type I and type II Pseudohypoaldosteronism. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1842–1845, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilson FH, Disse-Nicodeme S, Choate KA, Ishikawa K, Nelson-Williams C, Desitter I, Gunel M, Milford DV, Lipkin GW, Achard JM, Feely MP, Dussol B, Berland Y, Unwin RJ, Mayan H, Simon DB, Farfel Z, Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP: Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science 293: 1107–1112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lazrak A, Liu Z, Huang CL: Antagonistic regulation of ROMK by long and kidney-specific WNK1 isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1615–1620, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rinehart J, Kahle KT, de Los Heros P, Vazquez N, Meade P, Wilson FH, Hebert SC, Gimenez I, Gamba G, Lifton RP: WNK3 kinase is a positive regulator of NKCC2 and NCC, renal cation-Cl- cotransporters required for normal blood pressure homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16777–16782, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang CL, Angell J, Mitchell R, Ellison DH: WNK kinases regulate thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransport. J Clin Invest 111: 1039–1045, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Snyder PM, Fejes-Toth G: The kidney-specific WNK1 isoform is induced by aldosterone and stimulates epithelial sodium channel-mediated Na+ transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17434–17439, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCormick JA, Ellison DH: The WNKs: Atypical protein kinases with pleiotropic actions. Physiol Rev 9:177–219, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subramanya AR, Yang CL, McCormick JA, Ellison DH: WNK kinases regulate sodium chloride and potassium transport by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. Kidney Int 70: 630–634, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, Iemura S, Uchida S, Natsume T, Matsumoto K, Shibuya H: WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J Biol Chem 280: 42685–42693, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HK, Moleleki N, Vandewalle A, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Alessi DR: Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci 121: 675–684, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen SY, Bhargava A, Mastroberardino L, Meijer OC, Wang J, Buse P, Firestone GL, Verrey F, Pearce D: Epithelial sodium channel regulated by aldosterone-induced protein sgk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2514–2519, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang F, Bohmer C, Palmada M, Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Vallon V: (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol Rev 86: 1151–1178, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradbury NA, Bridges RJ: Role of membrane trafficking in plasma membrane solute transport. Am J Physiol 267: C1–C24, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang CL, Zhu X, Ellison DH: The thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter is regulated by a WNK kinase signaling complex. J Clin Invest 117: 3403–3411, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang CL, Zhu X, Wang Z, Subramanya AR, Ellison DH: Mechanisms of WNK1 and WNK4 interaction in the regulation of thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransport. J Clin Invest 115: 1379–1387, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anselmo AN, Earnest S, Chen W, Juang YC, Kim SC, Zhao Y, Cobb MH: WNK1 and OSR1 regulate the Na+, K+, 2Cl- cotransporter in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10883–10888, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ponce-Coria J, San-Cristobal P, Kahle KT, Vazquez N, Pacheco-Alvarez D, de Los Heros P, Juarez P, Munoz E, Michel G, Bobadilla NA, Gimenez I, Lifton RP, Hebert SC, Gamba G: Regulation of NKCC2 by a chloride-sensing mechanism involving the WNK3 and SPAK kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 8458–8463, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR: The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon's hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J 391: 17–24, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zagorska A, Pozo-Guisado E, Boudeau J, Vitari AC, Rafiqi FH, Thastrup J, Deak M, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Prescott AR, Alessi DR: Regulation of activity and localization of the WNK1 protein kinase by hyperosmotic stress. J Cell Biol 176: 89–100, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu BE, Stippec S, Chu PY, Lazrak A, Li XJ, Lee BH, English JM, Ortega B, Huang CL, Cobb MH: WNK1 activates SGK1 to regulate the epithelial sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 10315–10320, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butterworth MB: Regulation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by membrane trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 1166–1177, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Subramanya AR, Ellison DH: Sorting out lysosomal trafficking of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl Co-transporter. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 7–9, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai H, Cebotaru V, Wang YH, Zhang XM, Cebotaru L, Guggino SE, Guggino WB: WNK4 kinase regulates surface expression of the human sodium chloride cotransporter in mammalian cells. Kidney Int 69: 2162–2170, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Golbang AP, Cope G, Hamad A, Murthy M, Liu CH, Cuthbert AW, O'Shaughnessy KM: Regulation of the expression of the Na/Cl cotransporter by WNK4 and WNK1: Evidence that accelerated dynamin-dependent endocytosis is not involved. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1369–F1376, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Subramanya AR, Liu J, Ellison DH, Wade JB, Welling PA: WNK4 diverts the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter to the lysosome and stimulates AP-3 interaction. J Biol Chem 284: 18471–18480, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou B, Zhuang J, Gu D, Wang H, Cebotaru L, Guggino WB, Cai H: WNK4 enhances the degradation of NCC through a sortilin-mediated lysosomal pathway. J AM Soc Nephrol 21: 82–92, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ellison DH, Yang CL: WNK kinases interact with SNARE proteins to regulate NCC activity. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 66A, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glover M, Zuber AM, O'Shaughnessy KM: Renal and brain isoforms of WNK3 have opposite effects on NCCT expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1314–1322, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiga M, Rai T, Yang SS, Ohta A, Takizawa T, Sasaki S, Uchida S: Dietary salt regulates the phosphorylation of OSR1/SPAK kinases and the sodium chloride cotransporter through aldosterone. Kidney Int 74: 1403–1409, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rozansky DJ, Cornwall T, Subramanya AR, Rogers S, Yang YF, David LL, Zhu X, Yang CL, Ellison DH: Aldosterone mediates activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter through an SGK1 and WNK4 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest 119: 2601–2612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van der Lubbe N, Lim C, Meima M, Fenton RA, Danser AH, Zietse R, Hoorn EJ: Angiotensin II regulates the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter through SPAK independently of aldosterone. Kidney Int 79: 66–76, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. San-Cristobal P, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Richardson C, Ring AM, Vazquez N, Rafiqi FH, Chari D, Kahle KT, Leng Q, Bobadilla NA, Hebert SC, Alessi DR, Lifton RP, Gamba G: Angiotensin II signaling increases activity of the renal Na-Cl cotransporter through a WNK4-SPAK-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4384–4389, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mutig K, Saritas T, Uchida S, Kahl T, Borowski T, Paliege A, Bohlick A, Bleich M, Shan Q, Bachmann S: Short-term stimulation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F502–F509, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pedersen NB, Hofmeister MV, Rosenbaek LL, Nielsen J, Fenton RA: Vasopressin induces phosphorylation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule. Kidney Int 78: 160–169, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gimenez I, Forbush B: Regulatory phosphorylation sites in the NH2 terminus of the renal Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1341–F1345, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reiche J, Theilig F, Rafiqi FH, Militz D, Mutig K, Todiras M, Christensen EI, Ellison DH, Bader M, Nykjaer A, Bachmann S, Alessi D, Willnow TE: SORLA/SORL1 functionally interacts with SPAK to control renal activation of Na+-K+-Cl- cotransporter 2. Mol Cell Biol 30: 3027–3037, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. He G, Wang HR, Huang SK, Huang CL: Intersectin links WNK kinases to endocytosis of ROMK1. J Clin Invest 117: 1078–1087, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang CL, Yang SS, Lin SH: Mechanism of regulation of renal ion transport by WNK kinases. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 519–525, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fang L, Garuti R, Kim BY, Wade JB, Welling PA: The ARH adaptor protein regulates endocytosis of the ROMK potassium secretory channel in mouse kidney. J Clin Invest 119: 3278–3289, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adrogue HJ, Madias NE: Sodium and potassium in the pathogenesis of hypertension. N Engl J Med 356: 1966–1978, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halperin ML, Cheema-Dhadli S, Lin SH, Kamel KS: Control of potassium excretion: A Paleolithic perspective. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 430–436, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Masilamani S, Kim GH, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA: Aldosterone-mediated regulation of ENaC alpha, beta, and gamma subunit proteins in rat kidney. J Clin Invest 104: R19–R23, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim GH, Masilamani S, Turner R, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA: The thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter is an aldosterone-induced protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14552–14557, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beesley AH, Hornby D, White SJ: Regulation of distal nephron K+ channels (ROMK) mRNA expression by aldosterone in rat kidney. J Physiol 509:629–634, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wald H, Garty H, Palmer LG, Popovtzer MM: Differential regulation of ROMK expression in kidney cortex and medulla by aldosterone and potassium. Am J Physiol 275: F239–F245, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vasuvattakul S, Quaggin SE, Scheich AM, Bayoumi A, Goguen JM, Cheema-Dhadli S, Halperin ML: Kaliuretic response to aldosterone: influence of the content of potassium in the diet. Am J Kidney Dis 21: 152–160, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Lifton RP: Regulation of diverse ion transport pathways by WNK4 kinase: A novel molecular switch. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16: 98–103, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schambelan M, Sebastian A, Rector FC, Jr: Mineralocorticoid-resistant renal hyperkalemia without salt wasting (type II pseudohypoaldosteronism): Role of increased renal chloride reabsorption. Kidney Int 19: 716–727, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Take C, Ikeda K, Kurasawa T, Kurokawa K: Increased chloride reabsorption as an inherited renal tubular defect in familial type II pseudohypoaldosteronism. N Engl J Med 324: 472–476, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Reilly M, Marshall E, Macgillivray T, Mittal M, Xue W, Kenyon CJ, Brown RW: Dietary electrolyte-driven responses in the renal WNK kinase pathway in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2402–2413, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wade JB, Fang L, Liu J, Li D, Yang CL, Subramanya AR, Maouyo D, Mason A, Ellison DH, Welling PA: WNK1 kinase isoform switch regulates renal potassium excretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8558–8563, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McCormick JA, Yang CL, Ellison DH: WNK kinases and renal sodium transport in health and disease: An integrated view. Hypertension 51: 588–596, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takahashi N, Chernavvsky DR, Gomez RA, Igarashi P, Gitelman HJ, Smithies O: Uncompensated polyuria in a mouse model of Bartter's syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5434–5439, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Loffing J, Vallon V, Loffing-Cueni D, Aregger F, Richter K, Pietri L, Bloch-Faure M, Hoenderop JG, Shull GE, Meneton P, Kaissling B: Altered renal distal tubule structure and renal Na(+) and Ca(2+) handling in a mouse model for Gitelman's syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2276–2288, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schultheis PJ, Lorenz JN, Meneton P, Nieman ML, Riddle TM, Flagella M, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Miller ML, Shull GE: Phenotype resembling Gitelman's syndrome in mice lacking the apical Na+-Cl- cotransporter of the distal convoluted tubule. J Biol Chem 273: 29150–29155, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Morris RG, Hoorn EJ, Knepper MA: Hypokalemia in a mouse model of Gitelman's syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1416–F1420, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chang SS, Grunder S, Hanukoglu A, Rosler A, Mathew PM, Hanukoglu I, Schild L, Lu Y, Shimkets RA, Nelson-Williams C, Rossier BC, Lifton RP: Mutations in subunits of the epithelial sodium channel cause salt wasting with hyperkalaemic acidosis, pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1. Nat Genet 12: 248–253, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rubera I, Loffing J, Palmer LG, Frindt G, Fowler-Jaeger N, Sauter D, Carroll T, McMahon A, Hummler E, Rossier BC: Collecting duct-specific gene inactivation of alphaENaC in the mouse kidney does not impair sodium and potassium balance. J Clin Invest 112: 554–565, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wulff P, Vallon V, Huang DY, Volkl H, Yu F, Richter K, Jansen M, Schlunz M, Klingel K, Loffing J, Kauselmann G, Bosl MR, Lang F, Kuhl D: Impaired renal Na(+) retention in the sgk1-knockout mouse. J Clin Invest 110: 1263–1268, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vallon V, Schroth J, Lang F, Kuhl D, Uchida S: Expression and phosphorylation of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter NCC in vivo is regulated by dietary salt, potassium, and SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F704–F712, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fejes-Toth G, Frindt G, Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Palmer LG: Epithelial Na+ channel activation and processing in mice lacking SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1298–F1305, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lalioti MD, Zhang J, Volkman HM, Kahle KT, Hoffmann KE, Toka HR, Nelson-Williams C, Ellison DH, Flavell R, Booth CJ, Lu Y, Geller DS, Lifton RP: Wnk4 controls blood pressure and potassium homeostasis via regulation of mass and activity of the distal convoluted tubule. Nat Genet 38: 1124–1132, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ohta A, Rai T, Yui N, Chiga M, Yang SS, Lin SH, Sohara E, Sasaki S, Uchida S: Targeted disruption of the Wnk4 gene decreases phosphorylation of Na-Cl cotransporter, increases Na excretion and lowers blood pressure. Hum Mol Genet 18: 3978–3986, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Welling PA, Chang YP, Delpire E, Wade JB: Multigene kinase network, kidney transport, and salt in essential hypertension. Kidney Int 77: 1063–1069, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yang SS, Lo YF, Wu CC, Lin SW, Yeh CJ, Chu P, Sytwu HK, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Lin SH: SPAK-knockout mice manifest Gitelman syndrome and impaired vasoconstriction. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1812– 1814, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rafiqi FH, Zuber AM, Glover M, Richardson C, Fleming S, Jovanovic S, Jovanovic A, O'Shaughnessy KM, Alessi DR: Role of the WNK-activated SPAK kinase in regulating blood pressure. EMBO Mol Med 2: 63–75, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hadchouel J, Delaloy C, Faure S, Achard JM, Jeunemaitre X: Familial hyperkalemic hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 208–217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Achard JM, Warnock DG, Disse-Nicodeme S, Fiquet-Kempf B, Corvol P, Fournier A, Jeunemaitre X: Familial hyperkalemic hypertension: Phenotypic analysis in a large family with the WNK1 deletion mutation. Am J Med 114: 495–498, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang SS, Morimoto T, Rai T, Chiga M, Sohara E, Ohno M, Uchida K, Lin SH, Moriguchi T, Shibuya H, Kondo Y, Sasaki S, Uchida S: Molecular pathogenesis of pseudohypoaldosteronism type II: Generation and analysis of a Wnk4(D561A/+) knockin mouse model. Cell Metab 5: 331–344, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McCormick JA, Nelson JH, Ellison DH: Over-expression of the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) is not sufficient to cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Delaloy C, Elvira-Matelot E, Clemessy M, Zhou XO, Imbert-Teboul M, Houot AM, Jeunemaitre X, Hadchouel J: Deletion of WNK1 first intron results in misregulation of both isoforms in renal and extrarenal tissues. Hypertension 52: 1149–1154, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hadchouel J, Soukaseum C, Büsst C, Zhou XO, Baudrie V, Zürrer T, Cambillau M, Elghozi JL, Lifton RP, Loffing J, Jeunemaitre X: Decreased ENaC expression compensates the increased NCC activity following inactivation of the kidney-specific isoform of WNK1 and prevents hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18109–18114, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Liu Z, Wang HR, Huang CL: Regulation of ROMK channel and K+ homeostasis by kidney-specific WNK1 kinase. J Biol Chem 284: 12198–12206, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Subramanya AR, Yang CL, Zhu X, Ellison DH: Dominant-negative regulation of WNK1 by its kidney-specific kinase-defective isoform. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F619–F624, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chobanian AV: Shattuck Lecture. The hypertension paradox: More uncontrolled disease despite improved therapy. N Engl J Med 361: 878–887, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS: Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104: 545–556, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Guyton AC: Blood pressure control: Special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science 252: 1813–1816, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hoorn EJ, van der Lubbe N, Zietse R: The renal WNK kinase pathway: A new link to hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1074–1077, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tobin MD, Raleigh SM, Newhouse S, Braund P, Bodycote C, Ogleby J, Cross D, Gracey J, Hayes S, Smith T, Ridge C, Caulfield M, Sheehan NA, Munroe PB, Burton PR, Samani NJ: Association of WNK1 gene polymorphisms and haplotypes with ambulatory blood pressure in the general population. Circulation 112: 3423–3429, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Newhouse SJ, Wallace C, Dobson R, Mein C, Pembroke J, Farrall M, Clayton D, Brown M, Samani N, Dominiczak A, Connell JM, Webster J, Lathrop GM, Caulfield M, Munroe PB: Haplotypes of the WNK1 gene associate with blood pressure variation in a severely hypertensive population from the British Genetics of Hypertension study. Hum Mol Genet 14: 1805–1814, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Osada Y, Miyauchi R, Goda T, Kasezawa N, Horiike H, Iida M, Sasaki S, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K: Variations in the WNK1 gene modulates the effect of dietary intake of sodium and potassium on blood pressure determination. J Hum Genet 54: 474–478, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Turner ST, Schwartz GL, Chapman AB, Boerwinkle E: WNK1 kinase polymorphism and blood pressure response to a thiazide diuretic. Hypertension 46: 758–765, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Newhouse S, Farrall M, Wallace C, Hoti M, Burke B, Howard P, Onipinla A, Lee K, Shaw-Hawkins S, Dobson R, Brown M, Samani NJ, Dominiczak AF, Connell JM, Lathrop GM, Kooner J, Chambers J, Elliott P, Clarke R, Collins R, Laan M, Org E, Juhanson P, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Eyheramendy S, Cappuccio FP, Ji C, Iacone R, Strazzullo P, Kumari M, Marmot M, Brunner E, Caulfield M, Munroe PB: Polymorphisms in the WNK1 gene are associated with blood pressure variation and urinary potassium excretion. PLoS One 4: e5003, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sun ZJ, Li Y, Lu JY, Ding Q, Liang Y, Shi JP, Li-Ling J, Zhao YY: Association of Ala589Ser polymorphism of WNK4 gene with essential hypertension in a high-risk Chinese population. J Physiol Sci 59: 81–86, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Manunta P, Lavery G, Lanzani C, Braund PS, Simonini M, Bodycote C, Zagato L, Delli Carpini S, Tantardini C, Brioni E, Bianchi G, Samani NJ: Physiological interaction between alpha-adducin and WNK1-NEDD4L pathways on sodium-related blood pressure regulation. Hypertension 52: 366–372, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ji W, Foo JN, O'Roak BJ, Zhao H, Larson MG, Simon DB, Newton-Cheh C, State MW, Levy D, Lifton RP: Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet 40: 592–599, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zambrowicz BP, Abuin A, Ramirez-Solis R, Richter LJ, Piggott J, BeltrandelRio H, Buxton EC, Edwards J, Finch RA, Friddle CJ, Gupta A, Hansen G, Hu Y, Huang W, Jaing C, Key BW, Jr., Kipp P, Kohlhauff B, Ma ZQ, Markesich D, Payne R, Potter DG, Qian N, Shaw J, Schrick J, Shi ZZ, Sparks MJ, Van Sligtenhorst I, Vogel P, Walke W, Xu N, Zhu Q, Person C, Sands AT: Wnk1 kinase deficiency lowers blood pressure in mice: a gene-trap screen to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 14109–14114, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yagi YI, Abe K, Ikebukuro K, Sode K: Kinetic mechanism and inhibitor characterization of WNK1 kinase. Biochemistry 48: 10255–10266, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tiwari S, Riazi S, Ecelbarger CA: Insulin's impact on renal sodium transport and blood pressure in health, obesity, and diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F974–F984, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Song J, Hu X, Riazi S, Tiwari S, Wade JB, Ecelbarger CA: Regulation of blood pressure, the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), and other key renal sodium transporters by chronic insulin infusion in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1055–F1064, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bickel CA, Verbalis JG, Knepper MA, Ecelbarger CA: Increased renal Na-K-ATPase NCC, and beta-ENaC abundance in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F639–F648, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ellison DH, Oyama TT, Yang CL, Rogers S, Beard DR, Komers R: Altered WNK4/NCC signaling in a rat model of insulin resistance. J AM Soc Nephrol 20: 100A, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tiwari S, Sharma N, Gill PS, Igarashi P, Kahn CR, Wade JB, Ecelbarger CM: Impaired sodium excretion and increased blood pressure in mice with targeted deletion of renal epithelial insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6469–6474, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hollenberg NK, Stevanovic R, Agarwal A, Lansang MC, Price DA, Laffel LM, Williams GH, Fisher ND: Plasma aldosterone concentration in the patient with diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int 65: 1435–1439, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]