Abstract

Brown adipocytes help to maintain body temperature by the expression of a unique set of genes that facilitate cellular metabolic events including uncoupling protein 1-dependent thermogenesis. The dissipation of energy in brown adipose tissue (BAT) is in stark contrast to white adipose tissue (WAT) which is the body's primary site of energy storage. However, adipose tissue is highly dynamic and upon cold exposure profound changes occur in WAT resulting in a BAT-like phenotype due to the presence of brown-in-white (BRITE) adipocytes. In our recent report, transcription profiling was used to identify the gene expression changes that underlie the browning process as well as the intrinsic differences between BAT and WAT. Neuregulin 4 was categorized as a cold-induced BAT gene encoding an adipokine that signals between adipocytes and nerve cells and likely to have a role in increasing adipose tissue innervation in response to cold.

Keywords: adipokine, adipocyte, Brown fat, BRITE adipocyte, beige adipocyte, metabolism, neuregulin, Nrg4, thermogenesis, white fat

Adipose tissue is a remarkably dynamic organ that responds to the external and internal environment. It is composed of discrete subcutaneous and visceral depots that contain different amounts of white adipocytes, specialized cells for energy storage, and brown adipocytes that serve to generate heat by thermogenesis. Some white adipose tissue (WAT) depots undergo profound changes, following acclimatization to cold temperatures that result in a phenotype characteristic of brown adipose tissue (BAT). The adipocytes within the white fat that display brown fat features, such as multilocular lipid droplets and inducible uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression, are termed “brown-in-white” (BRITE) or beige adipocytes.1 There has been a recent resurgence in the study of brown fat following the identification of functional deposits in adult humans.2 With obesity becoming an increasingly important global health issue due to its associated risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and various cancers, it is imperative that medical researchers identify novel approaches to improve metabolic health. As BAT contributes to energy expenditure, recruitment and activation brown fat has great potential as a therapeutic target to combat weight gain.

Differential Gene Expression in BAT and WAT

The fundamental histological and functional differences between adipose tissues including the multilocular and unilocular adipocyte morphology of BAT and WAT, respectively, and the site of thermogenesis in BAT have been known for many decades.3 The differential gene expression that underpins the key morphological and functional differences is yet to be fully elucidated. In a recent report, we utilized microarray technology to investigate intrinsic depot-specific differences in gene expression as well as the changes in response to environmental temperature.4 Thus, we profiled gene expression of interscapular BAT, inguinal subcutaneous WAT and the visceral mesenteric WAT depots from animals acclimatized for 10 d to either warm (28°C) or cold temperatures (6°C). The warm temperature is near thermoneutrality for the mouse so BAT activity is minimal whereas BAT is fully activated in the cold to maintain body temperature. It is clear that the discrete white fat depots respond very differently to the cold treatment with subcutaneous being highly responsive and the mesenteric being largely unresponsive. From our analysis were identified key depot-specific gene expression as well as cold-induced and genes that define the BRITE fat.

Adipose tissue gene profiling studies have been undertaken by other researchers although there are several inter-study design differences such as mouse strain, gender, temperature, and duration of acclimatization. To distil the congruent gene expression differences between BAT and WAT or induced by cold in WAT the gene lists from our work and other studies5,6 were compared and the top common hits are listed in Table 1. This post hoc analysis reveals the transcriptional adaptations, in response to cold, and intrinsic differences between mouse depots that are similarly modulated despite differing experimental paradigms.

Table 1.

Cross-study consistent gene expression changes in response to cold in WAT and enriched in BAT compared to WAT. Cold-regulated genes: Genes that were induced after cold acclimatization in WAT, in both GSE510804 and GSE134325 microarray studies. The data were accessed from NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus26 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). BAT genes: Genes listed are more highly expressed in BAT vs Subcut WAT, in both GSE51080 and GSE440596 The top 25 genes common to 2 datasets are presented following comparison of significantly differentially expressed genes ranked by fold change

| Cold-regulated genes* | Function | BAT genes† | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elovl3 | fatty acid biosynthetic process27 | Zic1 | regulation of transcription, DNA-templated28 |

| 2 | Ucp1 | oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler activity29 | Ucp1 | oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler activity29 |

| 3 | Slc27a2 | long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity30 | Cpn2 | enzyme regulator activity31 |

| 4 | Fabp3 | long-chain fatty acid transporter activity32 | Fabp3 | long-chain fatty acid transporter activity32 |

| 5 | S100b | calcium-dependent protein binding33 | Slc27a2 | long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity30 |

| 6 | Acot11 | fatty acid metabolic process34 | 9130214F15Rik | — |

| 7 | Cpt1b | carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase activity35 | Kng1 | negative regulation of peptidase activity36 |

| 8 | Cox7a1 | oxidation-reduction process37 | Ppara | sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity38 |

| 9 | Gyk | glycerol-3-phosphate biosynthetic process39 | Pank1 | coenzyme A biosynthetic process40 |

| 10 | Kng1 | negative regulation of peptidase activity36 | Cpt1b | carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase activity35 |

| 11 | Otop1 | Anti-inflammatory activity41 | Me3 | oxidation-reduction process42 |

| 12 | PPARa | sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity38 | Plet1os (2310014F07Rik) | Non-coding RNA highly expressed in BAT, heart and skeletal muscle |

| 13 | Cpn2 | enzyme regulator activity31 | Cox7a1 | oxidation-reduction process37 |

| 14 | Pdk4 | regulation of fatty acid biosynthetic process7 | Gnas | G-protein β/gamma-subunit complex binding9 |

| 15 | Cyp2b10 | oxidation-reduction process | Gmpr | oxidation-reduction process43 |

| 16 | Dio2 | thyroid hormone metabolic process44 | Myo5b | regulation of protein localization45 |

| 17 | Pank1 | coenzyme A biosynthetic process40 | Acot11 | fatty acid metabolic process34 |

| 18 | Naglt1a (AI317395) | sodium-dependent glucose transporter (predicted) | Mapt | regulation of microtubule-based movement |

| 19 | Fbp2 | gluconeogenesis46 | Dio2 | thyroid hormone metabolic process44 |

| 20 | Aspg | lipid catabolic process47 | S100b | calcium-dependent protein binding33 |

| 21 | Esrrg | sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity48 | Ntrk3 | transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway49 |

| 22 | Idh3a | oxidation-reduction process50 | Esrrg | sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity48 |

| 23 | Slc25a20 | Mitochondrial substrate/solute carrier51 | Fbp2 | gluconeogenesis46 |

| 24 | 4931406C07Rik | ester hydrolase activity | Tspan18 | — |

| 25 | Cidea | Lipid metabolic process13 | Otop1 | Anti-inflammatory activity41 |

*The subcutaneous WAT gene lists were generated from data sets GSE51080 which used 10 week old female 129Sv mice acclimatized to either 28°C or 6°C for 10 d and GSE13432 which used 6–8 week old male C57BL/6 mice acclimatized to either 30°C or 4°C for 5 weeks. †For GSE51080, interscapular BAT and subcutaneous WAT was taken from 10 week old female 129Sv mice acclimatized to 28°C for 10 d For GSE44059 adipocytes were purified from interscapular BAT or subcutaneous WAT of young adult male C57BL/6 housed at 23°C.

For the genes induced following cold exposure the classical BAT genes were present including Ucp1, Cidea, Cpt1b, and PPARα. The majority of the transcripts on this list are important for fatty acid metabolism with the most highly regulated being Elovl3, Slc27a2, and Fabp3. It is noteworthy that the genes identified are involved in both anabolic and catabolic processes. In addition, there are high levels of Pdk4, which phosphorylates and inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes, leading to decreases in the formation of acetyl-CoA and a greater flux of pyruvate toward oxaloacetate and the glyceroneogenic pathway.7 This could be important at times when rates of lipolysis are high to maintain levels of glycerol-3-phosphate for fatty acid resterification to prevent depletion of the intracellular triglyceride pool.

Transcriptomic studies often identify expressed genes that have yet to been fully annotated or ascribed functions. One such cold-induced transcript is AI317395 which may have an important role in brown and BRITE adipocytes as analysis indicates it encodes a protein that is predicted to be a glucose transporter containing a major facilitator superfamily domain, general substrate transporter and is therefore termed sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1A (Naglt1a). High levels of glucose are taken up by BAT as illustrated by the application of positron emission tomography using fluorine-18 fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose to visualize this depot in humans.2 The elevated expression of the Naglt1a transcript raises the possibility that it could contribute to glucose uptake by BAT.

Examination of the genes more highly expressed in interscapular BAT compared to subcutaneous WAT in both our study4 and that of the Wolfrum group6 reveals a considerable overlap with the cold-regulated genes (14 out of 25 genes) including the enrichment of transcripts associated with fatty acid metabolism (Table 1). The transcriptional regulator zinc finger protein of the cerebellum (Zic1) is the top differentially expressed gene suggesting a potential role in the differential gene expression profile. It may be pertinent that Gnas is among the transcripts most enriched in BAT. This is in agreement with a recent RNA-seq study that identified this transcript as having the highest number of reads of any mRNA in BAT of the 13-lined ground squirrel.8 The gene encodes the stimulatory G-protein α subunit Gs-α. As β adrenergic receptors are the central mediators of BAT activation and coupled to Gs-α, the high expression of this G protein subunit may be integral to signal transduction in response to cold. Gnas is an imprinted gene9 and it is noteworthy that several other imprinted genes are linked with adipose biology. For example, Dlk1 is key regulator of the transition from preadipocyte to mature adipocyte10 and we found neuronatin to be one of the few genes more highly expressed in WAT compared to BAT.4 Other relevant genes that are predicted to be imprinted include Prdm16, Zic1, and Bmp8b.11

In our study, we undertook a strategy to define the “BRITE” transcriptome. For this, we determined the genes that were enriched in both BAT versus subcutaneous WAT, and BAT vs. mesenteric WAT (comparisons at 28°C) as well as increased in subcutaneous WAT by cold exposure. This analysis confirmed the association of Ucp1, Cidea, PGC-1α, Plin5, PPARα, and Otop1 with the “browning” of adipose tissue and also reveals additional genes that are part of the brown/”BRITE” transcription fingerprint including the fatty acid receptor Gpr120, the regulator of G protein signaling Rgs7, the mitochondrial membrane Ca2+/H+ antiporter Letm1, and signaling factor Nrg4.

Neuregulin 4 (Nrg4) an Adipokine Secreted by Brown Adipocytes

There is increasing evidence for an endocrine role of BAT. The secretion of factors including FGF21, VEGF-A, RBP4, FGF2, IL-1α, IL-6, IGF-1, BMP8B, and prostaglandins (reviewed in12) by BAT highlights its signaling capacity through endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine actions. We reported that NRG4 is a novel adipose tissue signaling factor that could have a key role in adipocyte-neuronal cross-talk.4 This epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like factor was identified as a member of the group of genes that define the “BRITE” transcription signature. Importantly, although visceral mesenteric WAT gene expression was largely unresponsive to cold, Nrg4 was one of only 5 genes identified by microarray as increased at 6°C vs 28°C (the others being Ucp1, Orm3, Cabc1, and Acsf2). BAT is the tissue that expresses the highest level of Nrg4 mRNA although significant amounts are detectable in gonadal and subcutaneous WAT as well as mammary gland. This pattern is remarkably similar to the more extensively studied BAT genes such as Cidea, which encodes a lipid droplet-associated protein.13 Furthermore, the expression of Cidea and Nrg4 is largely restricted to mature adipocytes with very low levels present in preadipocytes. The production of NRG4 by adipocytes is in contrast to other neurotrophic factors that primarily affect adipose tissue biology primarily through hypothalamic outflow pathways. Nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) are examples of factors produced by the central nervous system that affect energy balance (Reviewed in 14). NGF is however also produced by cultured brown adipocytes15 with a potential role in adipocyte-neuronal communication. A neurotrophic role for NRG4 is supported by studies of the related NRG1 that found it affected the development of neuronal progenitor stem cells.16

Like the other members of the neuregulin family (NRG 1–4), NRG4 contains a transmembrane domain with an adjacent extracellular EGF-like domain at the NH2-terminal.17 This region contains proteolytic cleavage-sensitive sites that allow the release of the biologically active EGF-like domain. To date, Nrg4 has been studied predominantly in cancers and is reported to be overexpressed in advanced-stage prostate cancer18 as well as a facilitating a survival signal in colon epithelial cells.19 It has been demonstrated previously that NRG4, in conditioned medium from transfected Cos7 cells or a chemically synthesized and refolded peptide, can elicit neuronal outgrowth in PC12-HER4 cells (a cell line derived from a rat adrenal medullary pheochromocytoma and stably expressing the receptor for NRG4, ERBB4).20 We found NRG4 protein was secreted by mature brown adipocytes, but not by brown preadipocytes.4 One of the key differences between brown and white adipose tissue is the degree of sympathetic innervation.21 Thus, NRG4 can be proposed as an important signaling factor that facilitates the innervation of adipose tissue. This is supported by the ability of brown adipocyte conditioned medium to promote neurite outgrowth by PC12-HER4 cells.4 The effect was specific for NRG4, as neurite outgrowth was prevented in conditioned media from adipocytes in which it was knocked down by shRNA interference.

Other growth factors such vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are reported to have important actions in brown adipose tissue. VEGF-A causes an increase in BAT thermogenesis and promotes the browning of WAT.5 It has multiple actions to affect adipocyte biology including vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, control of vascular permeability, and the recruitment of M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages.22 Of course the action of NRG4 is not necessarily restricted to adipocyte-nerve cell signaling and it may have other functions including autocrine actions particularly as Erbb4 is expressed in BAT and cultured brown adipocytes (MC unpublished observations). Dissection of the metabolic role of NRG4 has not been undertaken, but clues to its potential functions may be provided by studies in muscle where, for example, neuregulins are important for metabolism including glucose uptake.17 In addition, NRG4 signaling may modulate a central coregulator of brown fat gene expression, in manner similar to NRG1 that leads to phosphorylation of PGC-1α and its activation in muscle cells.23 As NRG4 is a growth factor, it may have paracrine effects to increase or maintain cell number during the cell turnover that may occur during adipose tissue remodeling from cold exposure. Alternatively, it could act to affect differentiation of preadipocytes as NRG1 acts to promote myoblast differentiation.24,25 Additional studies including in vivo investigations are required to fully delineate the roles of NRG4 in BAT and determine its ability to control sympathetic nerve innervation of adipose tissues. It is noteworthy that a recent investigation identified adipose tissue-derived NRG4 as a key regulator of hepatic lipolysis.52

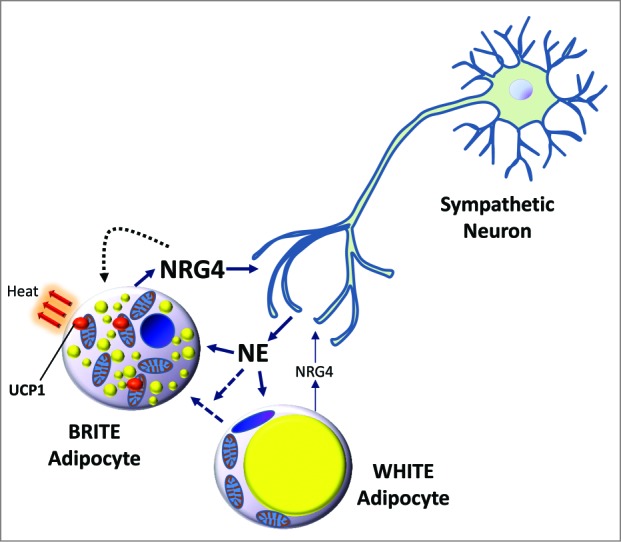

Following our analysis of mRNA expression in discrete adipose tissue depots we identified NRG4 as an adipokine primarily expressed by brown adipocytes that promotes neurite growth (Fig. 1) and therefore has the capacity to affect BAT sympathetic tone and facilitate thermogenic functions. As adult humans possess functional BAT NRG4 could be a new therapeutic target with the potential to increase BAT and BRITE adipocyte sensitivity to adrenergic signaling. The regulation of Nrg4 expression is only one example of the transcriptional events that underpin the WAT to BAT transition. Future investigations of the genes associated with the BRITE transcription signature could help develop new strategies to modulate energy balance for the treatment of metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

NRG4 is brown adipocyte adipokine that promotes neurite outgrowth. Neuregulin 4 (Nrg4) is more highly expressed in brown adipocytes compared to white adipocytes. Upon cold exposure, norepinephrine (NE) is secreted and activates brown fat as well as initiating the “browning” of white fat resulting in upregulated Nrg4 mRNA. NRG4 is secreted by brown adipocytes and can signal to neurons to promote neurite outgrowth. Thus, NRG4 is a brown/brown-in-white (BRITE) adipokine that has a potential role in enhancing sympathetic innervation of adipose tissues needed to activate thermogenic functions.

Funding

This work was supported by the BBSRC grant BB/H020233/1, the EU FP7 project DIABAT (HEALTH-F2–2011–278373), Wellcome Trust grant WT093082MA, and the Genesis Research Trust.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1. Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 2012; 150:366-76; PMID:22796012; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1509-17; PMID:19357406; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev 2004; 84:277-359; PMID:14715917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosell M, Kaforou M, Frontini A, Okolo A, Chan YW, Nikolopoulou E, Millership S, Fenech ME, MacIntyre D, Turner JO, et al. Brown and white adipose tissues: intrinsic differences in gene expression and response to cold exposure in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014; 306:E945-64; PMID:24549398; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00473.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xue Y, Petrovic N, Cao R, Larsson O, Lim S, Chen S, Feldmann HM, Liang Z, Zhu Z, Nedergaard J, et al. Hypoxia-independent angiogenesis in adipose tissues during cold acclimation. Cell Metab 2009; 9:99-109; PMID:19117550; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rulicke T, Wolfrum C. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:659-67; PMID:23624403; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cadoudal T, Distel E, Durant S, Fouque F, Blouin JM, Collinet M, Bortoli S, Forest C, Benelli C. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4: regulation by thiazolidinediones and implication in glyceroneogenesis in adipose tissue. Diabetes 2008; 57:2272-9; PMID:18519799; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db08-0477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hampton M, Melvin RG, Andrews MT. Transcriptomic analysis of brown adipose tissue across the physiological extremes of natural hibernation. PLoS One 2013; 8:e85157; PMID:24386461; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0085157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu S, Gavrilova O, Chen H, Lee R, Liu J, Pacak K, Parlow AF, Quon MJ, Reitman ML, Weinstein LS. Paternal versus maternal transmission of a stimulatory G-protein alpha subunit knockout produces opposite effects on energy metabolism. J Clin Invest 2000; 105:615-23; PMID:10712433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI8437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hudak CS, Sul HS. Pref-1, a gatekeeper of adipogenesis. Front Endocrinol 2013; 4:79; PMID:23840193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fendo.2013.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luedi PP, Dietrich FS, Weidman JR, Bosko JM, Jirtle RL, Hartemink AJ. Computational and experimental identification of novel human imprinted genes. Genome Res 2007; 17:1723-30; PMID:18055845; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.6584707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villarroya J, Cereijo R, Villarroya F. An endocrine role for brown adipose tissue? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013; 305:E567-72; PMID:23839524; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00250.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallberg M, Morganstein DL, Kiskinis E, Shah K, Kralli A, Dilworth SM, White R, Parker MG, Christian M. A functional interaction between RIP140 and PGC-1alpha regulates the expression of the lipid droplet protein CIDEA. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28:6785-95; PMID:18794372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.00504-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fargali S, Sadahiro M, Jiang C, Frick AL, Indall T, Cogliani V, Welagen J, Lin WJ, Salton SR. Role of neurotrophins in the development and function of neural circuits that regulate energy homeostasis. J Mol Neurosci 2012; 48:654-9; PMID:22581449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12031-012-9790-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nisoli E, Tonello C, Benarese M, Liberini P, Carruba MO. Expression of nerve growth factor in brown adipose tissue: implications for thermogenesis and obesity. Endocrinology 1996; 137:495-503; PMID:8593794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu Y, Ford BD, Mann MA, Fischbach GD. Neuregulin-1 increases the proliferation of neuronal progenitors from embryonic neural stem cells. Dev Biol 2005; 283:437-45; PMID:15949792; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guma A, Martinez-Redondo V, Lopez-Soldado I, Canto C, Zorzano A. Emerging role of neuregulin as a modulator of muscle metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010; 298:E742-50; PMID:20028964; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpendo.00541.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayes NV, Blackburn E, Smart LV, Boyle MM, Russell GA, Frost TM, Morgan BJ, Baines AJ, Gullick WJ. Identification and characterization of novel spliced variants of neuregulin 4 in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:3147-55; PMID:17545517; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernard JK, McCann SP, Bhardwaj V, Washington MK, Frey MR. Neuregulin-4 is a survival factor for colon epithelial cells both in culture and in vivo. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:39850-8; PMID:23033483; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.400846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayes NV, Newsam RJ, Baines AJ, Gullick WJ. Characterization of the cell membrane-associated products of the Neuregulin 4 gene. Oncogene 2008; 27:715-20; PMID:17684490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1210689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trayhurn P, Ashwell M. Control of white and brown adipose tissues by the autonomic nervous system. Proc Nutr Soc 1987; 46:135-42; PMID:3554253; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1079/PNS19870017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elias I, Franckhauser S, Bosch F. New insights into adipose tissue VEGF-A actions in the control of obesity and insulin resistance. Adipocyte 2013; 2:109-12; PMID:23805408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/adip.22880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Canto C, Pich S, Paz JC, Sanches R, Martinez V, Orpinell M, Palacín M, Zorzano A, Gumà A. Neuregulins increase mitochondrial oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle cells. Diabetes 2007; 56:2185-93; PMID:17563068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db06-1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ford BD, Han B, Fischbach GD. Differentiation-dependent regulation of skeletal myogenesis by neuregulin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 306:276-81; PMID:12788100; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00964-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim D, Chi S, Lee KH, Rhee S, Kwon YK, Chung CH, Kwon H, Kang MS. Neuregulin stimulates myogenic differentiation in an autocrine manner. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:15395-400; PMID:10336427; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 2002; 30:207-10; PMID:11752295; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/30.1.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zadravec D, Brolinson A, Fisher RM, Carneheim C, Csikasz RI, Bertrand-Michel J, Borén J, Guillou H, Rudling M, Jacobsson A. Ablation of the very-long-chain fatty acid elongase ELOVL3 in mice leads to constrained lipid storage and resistance to diet-induced obesity. FASEB J 2010; 24:4366-77; PMID:20605947; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.09-152298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ali RG, Bellchambers HM, Arkell RM. Zinc fingers of the cerebellum (Zic): transcription factors and co-factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012; 44:2065-8; PMID:22964024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicholls DG, Bernson VS, Heaton GM. The identification of the component in the inner membrane of brown adipose tissue mitochondria responsible for regulating energy dissipation. Experientia Supplementum 1978; 32:89-93; PMID:348493; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-0348-5559-4_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jia Z, Pei Z, Maiguel D, Toomer CJ, Watkins PA. The fatty acid transport protein (FATP) family: very long chain acyl-CoA synthetases or solute carriers? J Mol Neurosci 2007; 33:25-31; PMID:17901542; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12031-007-0038-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matthews KW, Mueller-Ortiz SL, Wetsel RA. Carboxypeptidase N: a pleiotropic regulator of inflammation. Mol Immunol 2004; 40:785-93; PMID:14687935; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vergnes L, Chin R, Young SG, Reue K. Heart-type fatty acid-binding protein is essential for efficient brown adipose tissue fatty acid oxidation and cold tolerance. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:380-90; PMID:21044951; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.184754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goncalves CA, Leite MC, Guerra MC. Adipocytes as an Important Source of Serum S100B and Possible Roles of This Protein in Adipose Tissue. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2010; 2010:790431; PMID:20672003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2010/790431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adams SH, Chui C, Schilbach SL, Yu XX, Goddard AD, Grimaldi JC, Lee J, Dowd P, Colman S, Lewin DA. BFIT, a unique acyl-CoA thioesterase induced in thermogenic brown adipose tissue: cloning, organization of the human gene and assessment of a potential link to obesity. Biochem J 2001; 360:135-42; PMID:11696000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/0264-6021:3600135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van der Leij FR, Cox KB, Jackson VN, Huijkman NC, Bartelds B, Kuipers JR, Dijkhuizen T, Terpstra P, Wood PA, Zammit VA, et al. Structural and functional genomics of the CPT1B gene for muscle-type carnitine palmitoyltransferase I in mammals. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:26994-7005; PMID:12015320; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M203189200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Merkulov S, Zhang WM, Komar AA, Schmaier AH, Barnes E, Zhou Y, Lu X, Iwaki T, Castellino FJ, Luo G, et al. Deletion of murine kininogen gene 1 (mKng1) causes loss of plasma kininogen and delays thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:1274-81; PMID:18000168; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2007-06-092338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee I, Huttemann M, Liu J, Grossman LI, Malek MH. Deletion of heart-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7a1 impairs skeletal muscle angiogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation. J Physiol 2012; 590:5231-43; PMID:22869013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology 1996; 137:354-66; PMID:8536636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kiskinis E, Chatzeli L, Curry E, Kaforou M, Frontini A, Cinti S, Montana G, Parker MG, Christian M. RIP140 represses the "brown-in-white" adipocyte program including a futile cycle of triacyclglycerol breakdown and synthesis. Mol Endocrinol 2014; 28:me20131254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rock CO, Karim MA, Zhang YM, Jackowski S. The murine pantothenate kinase (Pank1) gene encodes two differentially regulated pantothenate kinase isozymes. Gene 2002; 291:35-43; PMID:12095677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00564-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang GX, Cho KW, Uhm M, Hu CR, Li S, Cozacov Z, Xu AE, Cheng JX, Saltiel AR, Lumeng CN, et al. Otopetrin 1 protects mice from obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction through attenuating adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes 2014; 63:1340-52; PMID:24379350; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Loeber G, Maurer-Fogy I, Schwendenwein R. Purification, cDNA cloning and heterologous expression of the human mitochondrial NADP(+)-dependent malic enzyme. Biochem J 1994; 304 (Pt 3):687-92; PMID:7818469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salvatore D, Bartha T, Larsen PR. The guanosine monophosphate reductase gene is conserved in rats and its expression increases rapidly in brown adipose tissue during cold exposure. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:31092-6; PMID:9813009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Croteau W, Davey JC, Galton VA, St Germain DL. Cloning of the mammalian type II iodothyronine deiodinase. A selenoprotein differentially expressed and regulated in human and rat brain and other tissues. J Clin Invest 1996; 98:405-17; PMID:8755651; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI118806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roland JT, Bryant DM, Datta A, Itzen A, Mostov KE, Goldenring JR. Rab GTPase-Myo5B complexes control membrane recycling and epithelial polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2789-94; PMID:21282656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1010754108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gizak A, Maciaszczyk E, Dzugaj A, Eschrich K, Rakus D. Evolutionary conserved N-terminal region of human muscle fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase regulates its activity and the interaction with aldolase. Proteins 2008; 72:209-16; PMID:18214967; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.21909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karamitros CS, Konrad M. Human 60-kDa lysophospholipase contains an N-terminal L-asparaginase domain that is allosterically regulated by L-asparagine. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:12962-75; PMID:24657844; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.545038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dixen K, Basse AL, Murholm M, Isidor MS, Hansen LH, Petersen MC, Madsen L, Petrovic N, Nedergaard J, Quistorff B, et al. ERRgamma enhances UCP1 expression and fatty acid oxidation in brown adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21:516-24; PMID:23404793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/oby.20067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McGregor LM, Baylin SB, Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Nelkin BD. Molecular cloning of the cDNA for human TrkC (NTRK3), chromosomal assignment, and evidence for a splice variant. Genomics 1994; 22:267-72; PMID:7806211; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/geno.1994.1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huh TL, Kim YO, Oh IU, Song BJ, Inazawa J. Assignment of the human mitochondrial NAD+ -specific isocitrate dehydrogenase alpha subunit (IDH3A) gene to 15q25.1–>q25.2by in situ hybridization. Genomics 1996; 32:295-6; PMID:8833160; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/geno.1996.0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Bakker JA, Waterham HR, Wanders RJ. Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency, clinical, biochemical and genetic aspects. Mol Aspects Med 2004; 25:521-32; PMID:15363639; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mam.2004.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang GX, Zhao XY, Meng ZX, Kern M, Dietrich A, Chen Z, Cozacov Z, Zhou D, Okunade AL, Su X, Li S, Blüher M, Lin JD. The brown fat-enriched secreted factor Nrg4 preserves metabolic homeostasis through attenuation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nat Med 2014; 20:1436-43; PMID: 25401691; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]