Abstract

A 35-year-old previously healthy man presented with orogenital ulcerations, high fever, weight loss and leg thrombosis. Antibiotics were ineffective. His symptoms persisted and 3 years later he suffered from exertional dyspnoea. Inflammatory markers were elevated and all cultures were negative. CT of the thorax showed bilateral pulmonary embolism and a mass attached to the septum of the right ventricle, as well as an occluded vena cava inferior. Histology of the cardiac mass revealed a thrombus. The pulmonary embolisation progressed despite treatment with full-dose dalteparin. After being diagnosed with Behçet's disease, a multisystemic large-vessel vasculitis, and treated with high-dose prednisolone and cyclophosphamide, his ulcerations and his symptoms of dyspnoea disappeared.

Background

This case of a rare manifestation of Behçet's disease was very informative and showed that early diagnosis is essential to prevent adverse outcome. The cardiologists, imaging specialists and rheumatologists involved in the care of the patient had previously never come across this cardiac manifestation of the disease.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old previously healthy Syrian man was incarcerated and tortured for 6 months in Syria. After being released, he presented with orogenital ulcerations, high fever, weight loss and suspected leg thrombosis. He received medical care in Jordan. Antibiotics were ineffective and supply of warfarin was insufficient for continuous anticoagulation. Three years later he was granted asylum to Sweden. He had recurrent orogenital ulcerations, poor appetite (due to the oral ulcerations) and had, furthermore, developed exertional dyspnoea.

Investigations

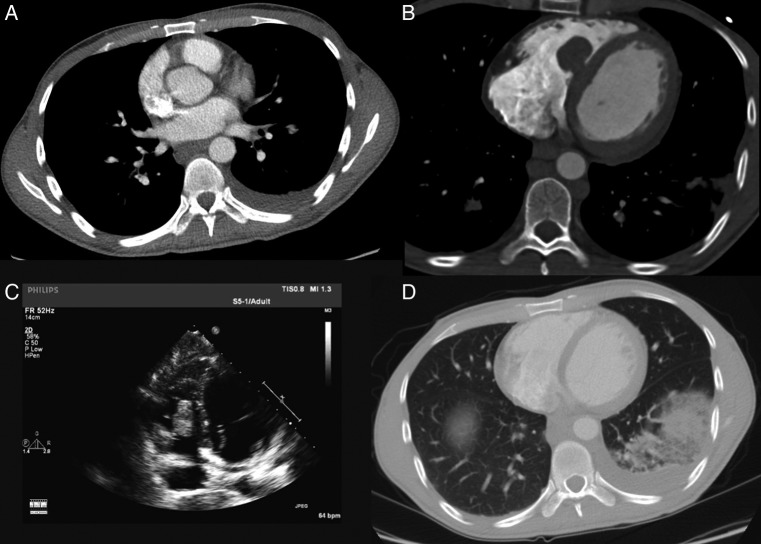

Physical examination revealed signs of cachexia, leg discolourations due to thrombophlebitis (figure 1A) and oral mucosal ulcerations (figure 1B), but was otherwise unremarkable. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated and all cultures were negative (table 1). CT angiography (figure 2A) showed bilateral pulmonary embolism. CT of the thorax (figure 2B) showed discrete pericardial fluid, a mass in the right ventricle (RV), left-sided pleural effusion and an occluded vena cava inferior with collaterals to the gastrointestinal tract. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed no hypertrophy, normal systolic function of the RV and left ventricle, no significant valve afflictions and no signs of pulmonary hypertension. A large 6×2 cm mass was attached to the septum of the RV below the tricuspid valve (figure 2C and video 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Thrombophlebitis and (B) mucosal ulcerations.

Table 1.

Laboratory tests and cultures on admission

| Laboratory tests | Values | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | 109 mg/L | <5 |

| Haemoglobin | 118 g/L | 130–170 |

| Leucocytes | 6.7×109/L | 3.5–9.0 |

| Thrombocytes | 261×109/L | 150–350 |

| Sodium | 137 mmol/L | 137–145 |

| Potassium | 4.1 mmol/L | 3.5–5.0 |

| Creatinine | 58 μmol/L | 60–105 |

| Troponin I | <2.0 ng/L | <35 |

| ESR | 76 mm | 2–13 |

| NT-proBNP | 185 ng/L | <90 |

| Further testing | Result |

|---|---|

| Blood culture | Negative |

| Skin culture from ulceration on scrotum | Negative |

| Faeces culture | No Camphylobacter, Salmonella or parasites |

| Hepatitis A, B and C | Negative |

| HIV | Negative |

| HSV 1 and 2 | Negative |

| Tularaemia | Negative |

| Lupus antibodies | Positive |

| Other phospholipid antibodies | Negative |

| Biopsies from ulcerations | Negative |

| BAL from bronchoscopy | No Mycobacterium, Aspergillus or Candida |

| IGRA-test | Negative |

| Brucellosis | Negative |

| Q-fever | Negative |

| Rickettsia | Negative |

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IGRA, interferon γ release assays; NT-proBNP, N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2.

(A) Bilateral pulmonary embolism and left-sided pleural fluid. (B) Mass in the right ventricle (RV) seen by CT of the thorax. (C) Mass in the RV seen by transthoracic echocardiography. (D) Decreased mass in the RV and lung infarction.

Video 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography showing intracardiac mass at diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

The large mass in the RV was first believed to be a tumour, but the localisation was unusual for a myxoma; sarcoma and lymphoma were also discussed. The possibility that it could be a thrombus was considered, as was vasculitis.

Treatment

The patient was treated with antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam) and full-dose dalteparin. A biopsy from the RV mass was obtained through right heart catheterisation, and histology showed a thrombus and no malignancy. Two weeks later, the patient suffered from chest pain. A new CT of the thorax and TTE showed that the RV mass had decreased in size but progression of pulmonary embolism and lung infarction were present (figure 2D and video 2).

Video 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography after further pulmonary embolisation.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was diagnosed with Behçet’s disease, a multisystemic large-vessel vasculitis. High-dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg) was administered daily for 1 month and he received proton-pump inhibitors and vitamin D substitution. Four days later, the oral ulcerations had disappeared, he gained 4 kg and ESR and C reactive protein (CRP) both normalised. Further, he was treated with colchicine, bactrim (prophylactic), continued with full-dose dalteparin and once a month for 6 months received cyclophosphamide.

Discussion

Behçet's disease is characterised by a wide clinical spectrum including recurrent orogenital ulcerations and uveitis, with vascular, neurological, articular, renal and gastrointestinal manifestations.1 The diagnosis is based on criteria proposed by the International Study Group for Behçet’s disease in 1990.2 Behçet’s disease is especially frequent along the ancient Silk Road, which extends from the Mediterranean region, through the Middle East, and all the way to eastern Asia.1 It is associated with the prevalence of certain human leucocyte antigens (HLAs), for example, HLA-B5 and HLA-B51.3 Up to one-third of patients have arterial or venous involvement.4 Our patient was tested and did not have HLA-B5 nor HLA-B51.

Cardiac manifestations include pancarditis, intracardiac thrombosis, endomyocardial fibrosis, coronary arteritis with or without myocardial infarction, and aneurysms of the coronary arteries or sinus of Valsalva.5 Arterial and venous involvement can both be present in a patient with Behçet’s disease, although the latter is more common.6 Behçet’s disease complicated by intracardiac thrombus most commonly occurs in young men from the Mediterranean region and the Middle East, and occurs most commonly in the right heart.7 Inflammatory markers, for example, ESR and CRP, are elevated in the majority of cases.8 Common abnormalities are superficial or deep thrombophlebitis of the lower extremities and thrombosis of the vena cava.6

A report on Behçet’s disease cases in one Turkish study, showed a clear male dominance (87% men), where 39% had vascular involvement, most commonly venous thrombosis, but approximately 8% had arterial lesions.9

Learning points.

Behçet’s disease has a higher incidence in Japan, the Mediterranean region and the Middle East.

The diagnosis of Behçet’s disease requires recurrent oral ulcerations at least three times in one year as well as 2/4 of the following criteria; recurrent genital ulcerations, ocular involvement, skin lesions and positive pathergy test.

Intracardial thrombus formation is an uncommon but serious manifestation.

Treatment consists of corticosteroids, azatioprin or methotrexate. Posterior uveitis or recurrent ulcerations may require cyclosporine, infliximab/adalimumab, cyclophosphamide, rituximab or mycophenolate mofetile.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N et al. Behcet's disease. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1284–91. 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.[No authors listed] Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. International Study Group for Behçet's disease. Lancet 1990;335:1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuki N, Inoko H, Ohno S. Pathogenic gene responsible for the predisposition to Behçet's disease. Int Rev Immunol 1997;14:33–48. 10.3109/08830189709116843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koc Y, Gullu I, Akpek G et al. Vascular involvement in Behçet's disease. J Rheumatol 1992;19:402–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geri G, Wechsler B, Huong DLT et al. Spectrum of cardiac lesions in Behçet disease: a series of 52 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91:25–34. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182428f49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calamia KT, Schirmer M, Melikoglu M. Major vessel involvement in Behçet's disease: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:24–31. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283410088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aksu T, Tufekcioglu O. Intracardiac thrombus in Behçet's disease: four new cases and a comprehensive literature review. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:1269–79. 9 Nov 2014 (Epub ahead of print) 10.1007/s00296-014-3174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saadoun D, Asli B, Wechsler B et al. Long-term outcome of arterial lesions in Behçet disease: a series of 101 patients. Medicine 2012;91:18–24. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182428126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duzgun N, Ates A, Aydintug OT et al. Characteristics of vascular involvement in Behçet's disease. Scand J Rheumatol 2006;35:65–8. 10.1080/03009740500255761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]