To the Editor,

Imatinib mesylate (IM) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets protein kinase, such as BCR-ABL, KIT, and platelet derived growth factor receptor- A and B. The efficacy and safety of IM in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) have been demonstrated in several clinical studies. In the studies using IM, it has been associated with variable adverse events, such as nausea, diarrhea, periorbital edema, fluid retention, and muscle cramp. But, such adverse events were mild and IM therapy was generally well tolerated. Pulmonary complications may occur during IM therapy and most of pulmonary complications have been related to pleural effusion or pulmonary edema due to fluid retention. However, interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with IM therapy has been rarely reported [1,2,3]. Here, we describe a patient, who had a prior treatment history of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, with histopathologically proven ILD after IM therapy for the treatment of recurrent GIST and improved by discontinuation of IM.

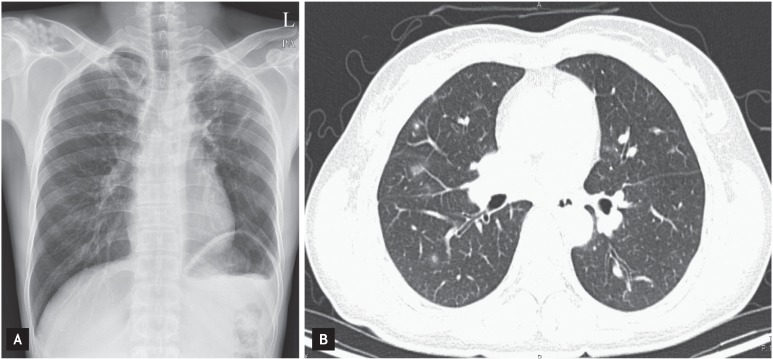

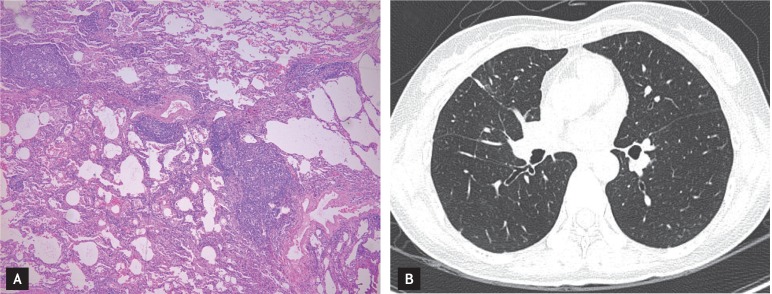

A 41-year-old woman with recurrent GIST in the distal rectum was visited to the clinic because of progressing nonproductive cough. She has been treated with IM at a dose of 400 mg/day for 8 months after complete surgical resection of recurrent rectal GIST. Her medical history was unremarkable, but she had a history of previous treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis 18 years ago. She has been well tolerated during the period of IM therapy. A complete blood count at clinic visit revealed a white-cell count of 4,690/mm3 with an absolute eosinophil count of 310/mm3, a hemoglobin level of 9.7 g/dL, and a platelet count of 260,000/mm3. On examination, blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, body temperature was 37.5℃, pulse rate was 90 beats per minute, and respiration rate was 20 breaths per minute. Physical examination and laboratory tests for infection and collagen vascular disease were unremarkable. A chest radiograph showed decreased lung volume with fibrotic scar lesions in the left upper lung field associated with the previous pulmonary tuberculosis, and a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest revealed multiple areas of ground-glass opacity (GGO) and nodular lesions with irregular margin predominantly in both lower lung fields (Fig. 1). To identify the nature of the nodular lesions, we performed video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection in the right lower lung. Histopathologic findings showed chronic interstitial inflammation with lymphoid hyperplasia and histiocyte aggregation, which were compatible with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 2A). IM therapy was discontinued at once because a causal relationship between ILD and IM could not be excluded. After the discontinuation of IM, a remarkable improvement of cough was seen within the next few weeks. One month later, HRCT was repeated and showed that the multiple GGO lesions were completely disappeared (Fig. 2B). IM has not been rechallenged to patient after the recovery of ILD and she is currently doing well without the recurrence of GIST.

Figure 1. (A) A chest radiograph revealed nodular opacity with fibrotic scar and pleural thickening at the left upper lung, associated with the previous infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. (B) A high-resolution computed tomographic scan demonstrated bilateral patchy and nodular lesions with areas of ground glass opacities predominantly in both lower lungs.

Figure 2. (A) A histopathologic examination revealed non-specific, chronic interstitial inflammation and the formation of lymphoid follicles, which was compatible with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (H&E, ×100). (B) A high-resolution computed tomography performed 1 month after the discontinuation of imatinib mesylate showed the complete resolution of previous lung lesions.

ILD is a rare adverse event associated with IM therapy. Until recently, several cases of IM-induced ILD have just been reported [1,2,3]. The incidence in the largest study from Japan was estimated approximately 0.5% [1]. A diagnosis of IM-induced ILD is made when there is a history of IM use and compatible radiologic and clinical findings [1,2,3]. Clinical manifestations of IM-induced ILD could vary from asymptomatic patients to those with severe symptoms [1]. Radiologic findings were also quite variable, including hypersensitivity reaction, interstitial pneumonitis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, nodular, peribronchovascular bundle, and diffuse alveolar damage patterns [1]. A histopathologic examination of the drug-induced pulmonary reactions are often non-specific, but could characterize the histopathologic pattern such as organizing pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and to excluded other processes [4]. However, it was not always possible to perform the histopathologic examination, which was frequently delayed or omitted owing to the severity of patient's symptoms. Thus, improvement of the radiologic findings after discontinuation of IM and, in some cases, accompanying corticosteroid therapy might aid the diagnosis of IM-induced ILD [1]. In the present case, typical pulmonary nodular pattern on radiologic study would raise the possibility of IM-induced ILD in a patient treated with IM and having pulmonary symptoms, and the idea was more supported by the histopathologic findings. Furthermore, other etiologic factors for ILD such as infection, collagen vascular diseases and drugs were not identified. Finally, multiple pulmonary nodules were completely disappeared within one month after the discontinuation of IM therapy. Therefore, the present case could be diagnosed as IM-induced ILD. Until recently, there has been lack of data for specific risk factors to the development of IM-induced ILD.

However, the Japanese study (n = 27) [1], which was the largest case series to date, revealed that preexisting lung disease, such as interstitial pneumonitis and chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), was present in more than 40% of patients with IM-induced ILD. Thus, they suggested that previous lung injuries might be associated with an increased risk of IM-induced ILD [1]. Pulmonary tuberculosis has been known to be associated with chronic airway inflammation and fibrosis, which are characteristics of COPD [5]. In the present case, she had findings of nodular opacity with fibrotic change and pleural thickening at the left upper lung associated with previous infection of M. tuberculosis. Although causal relationship between prior tuberculosis and IM-induced ILD might be unclear in our case, M. tuberculosis infection could be related with airway structural injury. Although the degree of airway injuries was correlated with the extent of disease assessed by imaging study, the history of M. tuberculosis infection itself was the strongest predictor of COPD [5]. Thus, our case raises the possibility of the association between IM-induced ILD and the airway injury related with prior infection of M. tuberculosis. Korea is the endemic area of M. tuberculosis infection. As described above, symptoms of IM-induced ILD varies from asymptomatic to fatal states. However, true incidence of IM-induced ILD has not been yet established in Korea. Thus, further studies are needed to investigate the incidence of IM-induced ILD and to evaluate the possibility of lung injury associated with prior pulmonary tuberculosis as a risk factor for the development of ILD.

In conclusion, we presented a rare case of ILD associated with IM therapy in a patient with GIST. It is important to have a high index of suspicion for this rare pulmonary toxicity when patients, in particular with preexisting lung disease, have unexplained lung infiltrates regardless of pulmonary symptoms if they are receiving the IM. The early evaluation with chest computed tomography and prompt withdrawal of IM with or without the use of corticosteroid is needed to avoid further detrimental effects of the drug. Furthermore, prospective study is needed to investigate the incidence of IM-induced ILD in patients with prior history of M. tuberculosis infection.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Ohnishi K, Sakai F, Kudoh S, Ohno R. Twenty-seven cases of drug-induced interstitial lung disease associated with imatinib mesylate. Leukemia. 2006;20:1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma CX, Hobday TJ, Jett JR. Imatinib mesylate-induced interstitial pneumonitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1578–1579. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosado MF, Donna E, Ahn YS. Challenging problems in advanced malignancy: case 3. Imatinib mesylate-induced interstitial pneumonitis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3171–3173. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camus P, Bonniaud P, Fanton A, Camus C, Baudaun N, Foucher P. Drug-induced and iatrogenic infiltrative lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:479–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]