Abstract

Background

Nurses are expected to empower their clients, but they cannot do so if they themselves feel powerless. They must become empowered before they can empower others. Some researchers have emphasized that understanding the concept of power is an important prerequisite of any empowerment program. While many authors have tried to define the concept of power, there is no comprehensive definition. This paper is an attempt to clarify the concept of power in nursing. It also would present a model describing the factors affecting nurse empowerment.

Methods

We chose the grounded-theory approach for analysis of the participants' experiences and their viewpoints regarding the concept of professional power in nursing. Semi-structured interviews and participant observation methods were used to gather the data. Forty-four participants were interviewed and 12 sessions of observation were carried out. The constant comparative analysis method was used.

Results

Six main themes emerged from the data: "Application of knowledge and skills", "Having authority", "Being self-confident", "Unification and solidarity", "Being supported" and "Organizational culture and structure". According to the participants, nurses' power is influenced by these six variables. A theoretical model was designed to represent the interrelationships between these six variables.

Conclusions

Nurses' power depends on gaining and applying professional knowledge and skills. Delegating authority and enhancing self-confidence of the nurses also help them to apply their knowledge in practice. Unification of the nurses and their mutual support play the key roles in development of their collective power and provide a base for better working conditions, professional independence and self-regulation.

Background

Nurses are the largest professional group within health service organizations [1]. They are expected to provide good-quality care by diagnosing and treating human responses to health and illness [2] and empower their clients [3] by moving them toward an independent, self-regulated, healthy life. But whether and how nurses can provide such care has been identified as being dependent on their professional power [4]. Tomey (2000) and Ellis and Hartley (1999) have also emphasized that no profession can provide suitable and qualified services unless its members feel power and have control over their own functions [5,6]. Thus, nurses need to be empowered themselves before embarking on a process of empowering others [7]. Considering the importance of nursing services in any health system, the 54th World Health Assembly recommended that programs be designed to strengthen and promote nurses [8]. Some authors believe that success in empowerment programs depends on understanding the concept of power. They emphasized that to empower nurses, the first step in the process is to determine their definition of power [9,10].

Power is an essentially contested concept [11], in that its meaning and people's perception of it vary greatly from person to person depending on their values, situations and experiences. It has been defined and analyzed in several ways by authors from different disciplines, including nursing [12].

The classical social psychologists have defined power interpersonally as influencing others' behavior by controlling the resources [13]. Lukes (1974) has considered power as an essentially unobservable force for controlling others' decisions. Functionalists view power as a resource held by individuals and groups in relation to the importance of their activities to society's goals. According to postmodernists, knowledge is power and these two do not exist in isolation from one another [4]. Feminists relate power to gender, but there is little consensus among them about the definition and dimensions of power [13].

A range of viewpoints concerning power also is discussed in the health literature. Griffin (2001) has discussed the concept from three popular perspectives in the health literature, including approaches to professionalization, the medical dominance perspective and the view of health care workplaces as organizations [14]. Based on her results, the power of nursing as a profession is linked to a number of factors including its status as a profession, the fact that the majority of its members are women and the extent to which nurses have knowledge and skills necessary to working with other disciplines. While Leksell et al. (2001) have defined power as conscious choosing and doing intentionally [15], some authors believe that the source of power in the health system is authority. However, Kuokkanen (2001) has stipulated that power is more than controlling actions; it is the manipulation of thoughts, attitudes and social relations [16].

The concept of power generally is not associated with nursing. Many members of the public perceive nursing as powerless and this belief is reinforced by nurses' perceptions of themselves as powerless [17]. Some authors have identified characteristics in the nursing profession that reflect a powerless and oppressed group during the last two decades [10,18]. Some researchers have also reported the same distinctive characteristics in their studies on Iranian nurses. They reported that Iranian nurses are not satisfied with their work setting. Nurses in these studies have expressed strong emotion concerning the lack of recognition in the workplace. They have also complained of lack of power and authority for controlling their practice and that doctors and managers do not respect their decisions [19-21]. According to Watson (1999), although the nurses try to gain power and status, they don't uniformly agree on the concept and the ways of reaching power [22].

In the recent years, the public and the government have criticized Iranian nurses because of the poor quality of patient care. They are searching for strategies to more appropriately use the workforce, such as decentralization and privatization [1]. However, the nurses' views about the factors that affect their clinical functions have rarely been investigated. It appears that the critics have forgotten that nurses cannot empower others if they feel powerless.

Thus, an important area for research is to obtain nurses' perspectives on professional power. It could be the first essential step for administrators and educators, when designing programs for empowering nurses. To this end a qualitative study was conducted on "Iranian nurses' understanding and experiences of professional power". The purpose was to clarify how Iranian nurses understand power, as well as the process and factors affecting their professional power.

Methods

Data were collected and analyzed using a grounded-theory approach [23]. The term grounded theory reflects the concept that theory emerging from this type of work is grounded in the data [24]. The grounded-theory approach has been used in nursing research since 1970. The studies have focused especially on nursing practice and nursing education [25]. Gaining and using power is clearly a process rather than static factors, which could suggest a grounded-theory approach. This approach was also selected because nurses' practice takes place in a multidisciplinary team and grounded theory focuses on identification, description and explanation of interactional process between and among individuals or groups within a given social context [23,26]. Data were collected by individual interviews, which were audiotaped, and through observations recorded in field notes.

Sampling and data collection

We used purposeful sampling at first and continued with theoretical sampling according to the codes and categories as they emerged. All nurses with more than five years of nursing experience who were currently working full-time in four large hospitals covered by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Tehran, Iran, were considered as potential participants. Sampling started from the surgical ward of the first hospital and was then extended to the other wards and hospitals. Data collection began with staff nurses. After interviewing three nurses and coding the transcripts, the codes and categories related to managerial support, organizational variables and nursing education led the researcher toward conducting interviews with head nurses, supervisors and a few key informants among higher-level managers, doctors, and nurse educators for the purpose of filling the gaps.

A total of 44 participants were interviewed, including 12 nurses, 12 head nurses, two supervisors, three nursing managers (matrons), three nurse educators, three senior nursing directors, two doctors (who were the executives of two hospitals) and seven members of the newly established Iranian Nursing Organization (INO). Each interview session lasted between 20 minutes and three hours, or 115 minutes on average.

The participants were representative for all four hospitals. Because there is a centralized outline in nursing education in Iran, all nurses presented with the same educational preparation. Also there is no system of recruitment in each hospital. Universities employ nurses and distribute them randomly to hospitals based on the number of nurses each hospital requires. Data were collected and analyzed during a six-month period in 2003.

Interviews

One of the researchers contacted each of the potential participants to explain the objectives and the research questions of the study. If the participant agreed to take part in the research, an appointment was made for the time of interview. Based on the participants' request, interviews were carried out two to three hours after starting their shifts because the workload was lower and nurses had time to be interviewed.

Individual semi-structured interviews in a private room at the workplace were the main method used for data collection. The interview guide was initially developed with the help of the two expert supervisors and consisted of core open-ended questions to allow respondents to explain their views and experiences as fully as possible.

At the beginning of each interview, participants were asked to describe one of their working shifts and then to explain their experiences and perceptions on "professional power" and the factors influencing it. For example, they were asked: "In your opinion, what is the meaning of 'power' in nursing? Explain some of your experiences in which you have felt power as a nurse. What factors have made you feel power in these experiences? How can we as nurses use or increase our power?"

Brief notes were made about the issues raised during the interview. Questions were asked later if these issues had not been spontaneously clarified. Some of the issues identified by the participants helped researchers to develop the interview guide over time. The interviews were conducted by the main researcher (MAH), tape recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed consecutively.

Observation

The main researcher conducted 12 sessions of participant observation in all four hospitals. Observations were conducted during the different shifts in emergency, medical, surgical and intensive care units and involved not only the nurses interviewed but also the other nurses present in the shift. Observations were carried out on the days appointed for interviewing the participants. The researcher was present in the ward with permission of the head nurse from the beginning of the duty hours, so that in two to three hours time before starting the interview the researcher could observe the dealings and behaviors.

Observation involved sitting in a corner of the ward and observing, or following individual nurses around. The researcher was asked by the head nurses not to care formally for patients, although at times assistance was given to the nurses at their request. The focus of participant observation was on nurses' interactions and dealings with their patients, colleagues, head nurses, supervisors and doctors, with particular emphasis on nurses' participation in decisions related to patient care and care setting. The researcher took notes during observations, with detailed observations written up the same day. These detailed notes were used as data concurrently with the interviews.

Data analysis

Data were collected and analyzed simultaneously, according to the grounded-theory approach. The interviews and observation data were analyzed concurrently using the constant comparative method. Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview took place. Therefore each interview provided the direction for the next.

Open, axial and selective coding were applied to the data [23]. During open coding, transcripts of each interview were reviewed multiple times and the data reduced to codes. The codes found to be conceptually similar in nature or related in meaning were grouped in categories. Codes and categories from each interview were compared with codes and categories from other interviews for common links.

Axial coding was concentrated on the conditions and situations that cause a phenomenon to take place and the strategies applied to control the phenomenon. This process allowed links to be made between categories to their subcategories, and then selective coding developed the main categories and their interrelations.

Although a variety of different levels of personnel were interviewed, themes that arose were consistent across interviews. Staff at different levels used different words to refer to the same concept, however. For example, while the managers used the word "authority," some nurses used the word "permission" or "right to do" to refer to this concept. Also, all participants mentioned the insufficient salary of nurses, but the managers and doctors believed that the governmental rules don't permit them to increase the nurses' salary. Interviewing stopped when data saturation occurred. Data were considered "saturated" when no more code could be identified and the categories were "coherent" or made sense.

Credibility was established through participants' revision as member check, prolonged engagement with participants and peer check. Maximum variation of sampling also confirmed the confirmability and credibility of data [27,28]. The participants were contacted after analysis and were given a full transcript of their coded interviews with a summary of the emergent themes to see whether the codes and themes were true to their experience. As a further validity check, two expert supervisors and three other faculty members did peer checking on about 45% of all transcripts. During this process the transcripts of interviews were given to them and they followed the same process as above to arrive at core themes. There was 90% or higher agreement between different raters.

Results were also checked with some of the nurses who did not participate in the research and confirmed the fitness of the results as well. These sampling strategies resulted in maximum variation sampling to occur and a vast range of views and experiences considered. The researcher tried to precisely document the direction of research and the decisions made, in order to preserve the "auditability" for the other researchers to follow the direction of the research. Prolonged engagement with participants and with the research environments helped the researcher to gain the participants' trust and enable them to better understand the research environments.

Ethical considerations

This study was carried out as part of a PhD thesis in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences gave permission for the study. Other ethical issues in this study involved the assurance of confidentiality and anonymity for the participants. All participants were informed of the purpose and design of the study and the voluntary nature of their participation. Written consent was sought from the participants for audiotaped interviews; the hospital directors and head nurses had also agreed to their participation and to participant observation.

Results

The individual characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Individual characteristics of the participants

| Total | Level of education | Sex |

Years of service |

Age |

||||

| BS | MS | PhD | Female | Male | ||||

| Staff nurse | 12 | 9 | 3 | - | 9 | 3 | 12/4 ± 5/7 | 32/7 ± 5/3 |

| Head nurse | 12 | 10 | 2 | - | 11 | 1 | 22/6 ± 6/2 | 52/8 ± 5/2 |

| Supervisor & matron | 5 | 4 | 1 | - | 3 | 2 | 19 ± 7/3 | 42/2 ± 7/4 |

| Senior nurse manager | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 24/3 ± 7/8 | 47/5 ± 7/6 |

| Educator | 3 | - | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 28 ± 1/5 | 50 ± 1 |

| Physician | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 19 ± 12/7 | 48 ± 11/3 |

| Members of INO | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 23 ± 11/4 | 42 ± 10/1 |

| Total | 44 | 25 | 14 | 5 | 28 | 16 | 19/3 ± 8/1 | 40/8 ± 8/3 |

Data analysis resulted in the identification of six themes, including "Application of knowledge and skills," "Having authority," "Being self-confident," "Unification and solidarity," "Being supported" and "Organizational culture and structure." Each theme will be discussed, followed by the conceptual model of the interconnectedness of these six themes.

Application of knowledge and skills

The participants emphasized the role of professional knowledge of a nurse in his/her power and considered that as one of the crucial factors in gaining power. According to one of the nurses: "A powerful nurse is the one who has rich knowledge and skill and is expert in his/her own job." (Nurse five) One of the supervisors also said: "The 'power' as a whole means 'ability' ... the level of power a nurse has depends on the level of her/his professional knowledge and experience. A powerful nurse is one who both has good knowledge and can use it well." (Supervisor two)

Though participants believed that having "professional knowledge and skills" is the basic prerequisite for gaining power, they don't consider it to be sufficient. They emphasized that power is gained only when the nursing knowledge is "applied and implemented" by the nurse. They clearly stated that: "The power of a nurse would only be exhibited through application of knowledge and skills in the provision of care for their clients."

Although power is not a visible and palpable thing, the nurses experienced it when they were able to care for their clients based on their clinical judgment (which definitely arose from their professional knowledge and skills) and observed effective outcomes for their clients.

One of the nurses described an experience in which she experienced power:

"When I was working in the neurological surgeries unit, a discopathic patient was brought from the operating room; one of his primary signs was leg pain. When he was brought, I noticed the patient's frequent complaining of leg pain. I went to his bedside and removed the blanket. Previously, he complained of pain in the right leg, but now he was complaining of pain in the left leg. I noted that the left leg's temperature was lower than that of the right. His pulse was slow. I immediately called the concerned doctor and also called and arranged for the operating room. The patient was taken to the operating room and an embolectomy was done. The doctor said that any delay in the operation would have led to the loss of the intact leg. Anyway, if my knowledge was poor, something would have happened. It was then that I felt power, because I felt that my proper knowledge and timely decision might have saved the patient." (Nurse 11)

Having authority

"Having authority" was a dominant theme in the participants' viewpoints. They frequently used such statements as "the right to do" or "the authority to do the duty without the necessity to get permission" to refer to the concept of "having authority". Although staff nurses and nursing managers pointed to different symbols of having authority, the relation between "power" (application of professional knowledge) and "authority" were so clear in their viewpoints that 36 participants referred to "authority" in explaining their experiences about '"power", and even considered them to be synonymous.

One of the senior nursing officers said: "Power means the 'authority' that one can have, and a person can be powerful only when he/she can decide on his/her own." (Senior nursing officer one)

Head nurses also consider power as an outcome of having authority. To them: "Power is the responsibility that is handed over to the man and is the right for him to perform many tasks that even an ordinary nurse can perform but he/she has not been allowed to." (Head nurse four).

The staff nurses also considered power as having authority to decide in their own territory of duty. They believe in power and authority as the means for the better and faster care of the patients. One nurse commented: "We don't want any more right than my real rights." (Nurse four) Another nurse stated: "I must have the right to do nursing care based on my diagnosis." (Nurse five)

From the participants' points of view, some internal and external factors affect the perception and use of authority by nurses. The external dimension that is considered a barrier to using their authority and power covers organizational factors such as job description, official rules, unbalanced nurse-patient ratios and increase in non-nursing duties.

The internal dimension goes back to the nurses' self-confidence in using their formal and informal authority. The following comments of two nurse-educators describe this point: "The power depends on the individuals; some people have power with the same authority, and some people do not." (Nursing trainer two) "When I was designated as the head nurse of the neurosurgery unit, I made an agreement with the chief doctor that when we observe the signs and symptoms of infection, we don't wait for them to come and order the culture. We also did many nursing interventions but now, many nurses wait for the doctor to order them." (Nursing trainer one)

Many of the participants felt frustration because they believed they had the knowledge and experience to make decisions, yet the doctors always had the final authority. One nurse commented: "We look after clients ... we work together (with doctors), but they have the authority. When I or one of my colleagues believes a patient is ready for discharge, we tell the doctor and all he does is turn around and say 'ah no, we'll keep him for another few days' – when there's no clinical reason why he should remain. We're the ones who look after them 24 hours a day, not for five minutes a day." (Nurse three)

Being self-confident

Self-confidence was another theme that emerged from data. Thirty-five participants emphasized the key role played by self-confidence in feeling and using power and authority, and a majority of them considered that as a synonym or a necessary base for power. They also identified the different factors and dimensions in self-confidence of the nurses. They believed that: "Self-confidence provides the nurse with the feeling of power and ability, and lack of confidence causes someone feel weak and unable to use his/her talents," so that she/he would avoid independent actions.

According to a clear statement of one of the head nurses: "Power depends on the individuals. Some people have the self-confidence to make use of their authority in their duty limits as a nurse or a nurse manager, while some are weak and unable to do so." (Head nurse five)

Participants emphasized the mutual relationship between power and self-confidence. In other words, power gives the nurse self-confidence, and self-confidence brings with it the feeling of power. One of the senior nurse managers commented in this regard: "Self-confidence brings power and vice versa; it is exactly mutual, and I have felt it many times. One day, they offered me the post of "deputy director" and asked whether I would accept it or not. I immediately said, "yes" because I had full confidence in doing it." (Senior nurse manager one)

According to participants, although self-confidence is rooted in one's personal characteristics and the social and work-related interactions, having adequate and job-related knowledge and information, together with the people's feeling of confidence and self-efficacy in doing something, provide them with the feeling of power and ability.

While the participants considered self-confidence as one of the main pillars in feeling and applying power, the majority of them complained of the "lack of self-confidence in nurses and nurse managers" and considered it as the root factor in "powerlessness and feeling of inferiority of nurses toward doctors." This is why they believe that the nurses' self-confidence must be strengthened.

They also pointed out that self-confidence of nurses is negatively affected by the wrong methods of education, social culture, role ambiguity and frequent cross-questioning and under-questioning of the scientific and technical competence of nurses. These factors cause a feeling of inefficiency, powerlessness, role conflict and lack of self-confidence in nurses and make them believe they are only means for carrying out the doctor's orders. When the researcher was observing in a surgical ward, he saw a patient who asked a nurse to inform him about his diet after the discharge. The nurse said: "you must wait until your doctor comes." The researcher asked the nurse why he did not educate the patient. The nurse said: "I don't know what exactly I must do. Am I allowed to give advice to a patient about his diet? Am I authorized to change the patient's position? I have been punished for such things many times. This is why I am uncertain and I did as I did."

Unification and solidarity

The participants emphasized the importance of unity and its role in professional power. They considered the unity of nurses and coming together in nursing unions as an efficient way to increase professional power. Although all participants focused on the necessity of unity among nurses and considered it the most important factor in gaining collective power, most of them pointed out the disunion among the nurses and considered it one of the reasons behind their weakness as a professional group. Two participants stated: "If there is something lacking in nursing, it is the unity that is mostly not present." (Trainer three) "The nurses do not support each other." (Nurse one)

This condition has made nurses accept the present situation. As one nurse said: "We are weak because we are not with each other. So we cannot use our power and are obliged to obey every order. We try to adapt to the situation and avoid any disagreement." (Nurse two)

According to the participants, the unsatisfied needs, heavy workloads and lack of time are the main barriers in the unification and solidarity of nurses. One supervisor commented: "The pressure of work, overloading of responsibilities and working overtime in other places just to fulfill their financial needs have made them so busy that they rarely have enough time to think over and find the root of this situation or find the ways to face it." (Supervisor one)

However, many of the nurses have concluded that unification and collective action are necessary steps in the development of their professional power. To them, coming together in legal and formal nursing organizations is the best solution in this regard. The following quotes of two supervisors confirm this: "This power must be created in these unions and organizations, and they must prove themselves at the social level." (Supervisor two) "I believe in the strong power of nursing, but if this power is provided to a special organization the nursing status will definitely improve beyond the present position. It is also revealed in the holy Quran that: the progress of a society is measured by each one of its individuals." (Supervisor one)

These statements not only indicate the necessity of unification and its role in the development of professional power, but to them, the presence of a talented leader in directing the existing energy is a must. One of the nurses also commented: "I hope nurses come together, to improve our condition and also to decide for our profession"; she was aware that collective power brings the possibility of better working conditions and professional self-regulation. The latter would make it possible for them to develop standards and regulations for their profession and define the limits of authority, responsibility and accountability of each member of the profession. Afterward, they will be able to apply their personal power and provide good-quality care for their clients.

Being supported

Nurses frequently emphasized the necessity of support. To them, support was characterized primarily as supportive management, and was considered an important factor in the development of their professional power. One head nurse commented: "Powerful nursing owes support, it must be supported, and the 'people in charge' should support it." (Head nurse one)

The participants' views and experiences on support were categorized under the three subheadings of: "provision of care facilities", "provision of financial welfare," and "provision of emotional support". Nurses have emphasized that support would bring them the feeling of power and would result in better-quality care.

But a feeling of being unsupported dominated the nurses. They believe that they are not supported by either the nursing or non-nursing superiors; therefore, they considered the nursing managerial system as "deficient." As two nurses said: "We don't know what this managerial system is for. They do nothing for us." (Nurse three) "We have no professional, financial, emotional and life support at all, and these are the supports that can give us necessary power." (Nurse 11)

According to the participants, managers have responsibility for the "provision of care facilities", but they don't do it properly. Shortage in the nursing workforce and lack of care facilities such as sheets, dressing equipment, wheelchairs and so on, made nurses unable to apply their professional knowledge. Consequently, they feel unable to meet their clients' needs, which gives them a feeling of inadequacy and powerlessness. One of the participants said: "When we have only two nurses for 37 patients, certainly they cannot provide good care. They can only monitor the blood pressure and give the drugs," (supervisor one)

The participants mentioned the "insufficient income of nurses" frequently, but what they found more objectionable was to witness the unjust distribution of income in the health system. All participants, (except two participating doctors) emphasized the significant difference between doctors' and nurses' income and considered it a symbol of injustice, lack of support and ignorance of the nursing services' value. "This made nurses preoccupied with financial difficulties and caused them not to be able to concentrate on their patients' problems." (Nurse educators two)

Nurses also emphasized the lack of "emotional support." They pointed out circumstances such as "despising and suppression of nurses," "taking the side of doctors in their conflict with the nurses" and "carelessness and inattention to nurses' problems", and considered them symbols for the lack of "emotional support."

The following statements contain clues to the unsupportive and oppressive behaviors of some of the nurse managers: "There is no one listening to our tales of suffering; we are complaining about our own colleagues – those who are in charge of us – because they never support us." (Head nurse one)

"Our matron shows off her power only before us, not others." (Nurse seven) "If something goes wrong in the hospital, the nursing office supports others rather than the nurses." (Head nurse six) Such experiences have taught nurses that any disagreement must be avoided. Therefore they are reluctant to assume responsibility and this reluctance has made them more powerless.

Organizational culture and structure

The structure and culture of the health care system was another important factor affecting nurses' power and also their participation in clinical decisions. Many organizational issues were mentioned by the participants in this research. These include factors such as lack of nurses' visibility within the organization, dissatisfaction with the way the organization is managed, lack of involvement in decision-making, inadequate staffing and lack of control over their practice setting.

As we mentioned earlier, nurses considered "authority" as an important prerequisite for implementing professional knowledge and skills, but the majority of nurses believed that organization-related variables such as job description have limited them. Also, some participants believed there was a physician-centered culture in the health care system that doesn't regard nurses' decisions and does not permit them to use their authority. One of the supervisors stated: "Now it is expected that nurses only obey orders, give the drugs, do the injections, monitor the blood pressures and write the nursing notes, but that they do not intervene independently." (Supervisor One) One nurse-educator also commented: "I think the system forces the nurses to ignore their own authority. For example, everyone who wants to enter an ICU must change his/her shoes. Nurses frequently have mentioned this rule, but most doctors did not do so, and the nurses were reprimanded. Finally nurses have ignored to do so."

Many nurses mentioned that factors such as inadequate manpower, unbalanced nurse-patient ratios and increase in non-nursing duties have decreased their relationship with patients and made them adopt a task-oriented working system that spontaneously acted as a barrier to applying knowledge and skills. Thus, conflict has arisen between nurses' perceived professional roles and the roles that the organization has imposed on nurses. This conflict has produced a great deal of stress for nurses, so that many nurses are seeking different work. One nurse said: "I don't know what I am. I don't know the meaning of my work. Am I a nurse, nurse's aide, worker, secretary or watchman? I am compelled to do the duties of all of them because there is not enough manpower for these duties. How can I be a good nurse with these difficulties?"

One head nurse also commented in this regard: "This ambiguity of the roles, along with the heavy workloads and a poor socioeconomic status, makes nurses depressed and angry and they wish to find another job."

Nurses also identified management style as being an important influence on nurses' power. But they believed there was an autocratic management style in the hospitals in which they worked. This management style resulted to an unsupportive atmosphere in the hospitals that does not value nurses and nursing services.

Although there was consensus that being valued was an enhancing factor for empowerment, nurses felt disempowered by not being involved as professionals. As one nurse stated: "We as nurses are not being valued by the top-level managers. I think it is very important that you feel valued by other members of the team and especially by your manager." (Nurse ten) Therefore nurses were not satisfied by their managers, and as one nurse said: "I think the nursing hierarchy disempowers many nurses." (Nurse two)

Some of the participants believed that the "prolonged background of task-oriented," "routine-centered work environment," and "contentment in carrying out the doctors' orders" have decreased the nurses' self-confidence and have caused an internalized dependency in nurses, so that many of them consider "independent steps" to be prohibited and feel an internal compulsion in getting permission from the doctors.

Discussion

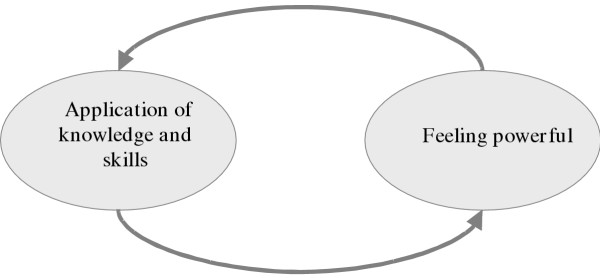

From the participants' point of view, the concept of professional power had a direct and mutual relation to application of knowledge and skills in nursing practice (fig. 1). In fact, they conceptualized professional power as: "the ability of a nurse to apply his/her professional knowledge and skills and provide nursing care based on the nurse's diagnosis, in response to the needs of their clients."

Figure 1.

Interaction between power and application of knowledge and skills

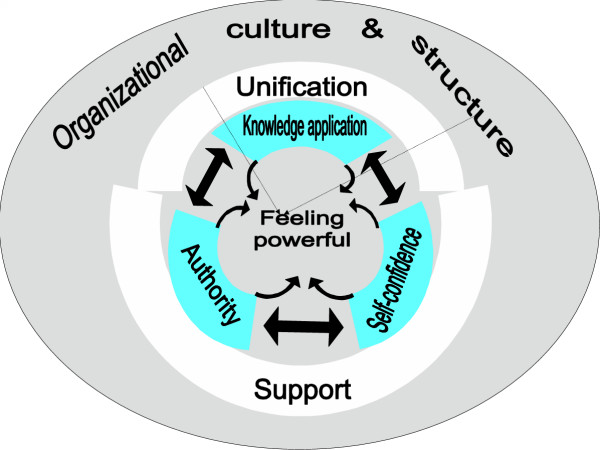

As presented in fig. 2, this ability has a close relationship with having authority and being self-confident. Though nurses have felt power in implementing their own knowledge and skills in their caring practice as well as in participating in clinical decisions, some other variables also affected their ability to exert their professional power in practice. Indeed, the pooled effect of these variables negatively has affected nurses' ability to make use of their professional power.

Figure 2.

Interactive relationships between variables affecting nurses' power

The theoretical model shown in fig. 2 represents the major themes, as well as the relationships among those variables influencing nurses' power. These variables as a whole represent the process by which nurses have felt themselves powerful or powerless.

Figure 2 shows that the six variables were grouped in three main interrelated categories. The first category was called "personal power" (the inner three-part circle in the model), which comes from the mutual effects of three processes i.e., "application of knowledge and skills", "having authority" and "self-confidence." The second category was named as "collective power" (the second two-part circle in the model) that comes from the interaction between two variables, i.e., "being supported" and "unification". "Organizational culture and structure" also emerged as the third category.

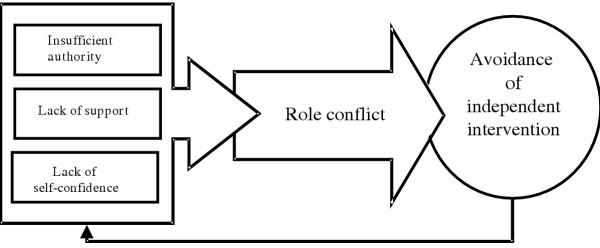

Data were examined to identify the core variable influencing the nurses' power. A careful review of the data and the themes that emerged proves that "organizational culture and structure" was the core variable affecting nurses' power. In fact it was the organizational structure and its physician-centered and routine-oriented culture that have made nurses just obey doctors and managers and carry out their orders. It became clear that the basic social psychological problem that nurses encountered was that of "role conflict."

Indeed, there was conflict between nurses' professional roles and the roles that organization imposed on the nurses. Patients need care, and nurses have the knowledge and skills to care for them, but they have not the authority, support and self-confidence to apply their own knowledge and skills. As a result, nurses feel tension and role conflict.

The basic social-psychological process that nurses used to deal with the conflict and tension was that of "avoidance." In fact, nurses were avoiding any independent caring intervention and only executed the doctors' orders. Actually, they have come to realize that the hospital system does not tolerate their power and any attempt to exerting their own professional power would result in tension and conflict. Therefore they have ignored their own power and only obey. This has made them weaker and more powerless. Figure 3 represents this process.

Figure 3.

The process inhibiting nurses' power

As presented in fig. 2, the participants in this research mentioned two aspects of professional power. According to the participants, personal power comes from professional knowledge and skills, levels of authority and self-confidence in applying them clinically. According to nurses, collective power also comes from unification and supporting each other. Pelletier et al. (2000) and Sneed (2001) have also emphasized the necessity of personal and collective power in nursing [29,30].

Having a wide range of professional knowledge, making the right decisions on the basis of this knowledge, and exerting these decisions in response to patients' needs are the most important conditions that have created the experience of personal power in nurses who participated in this study.

Knowledge is power [30], and those having knowledge can influence others. Nurses who have professional knowledge and use it in the context of efficient human relations gain credibility and a sense of power. In a qualitative content analysis of interviews of 30 nurses, they demonstrated that expertise; knowing how to do the job and possessing a wide range of knowledge were associated with the development of their professional power [31]. This has also been confirmed by Fulton (1997) [10] and Kubsch (1996) [32]. Benner et al. (1996) have also shown that nurses can deal with the situations at hand by acquisition of knowledge and skilled performance [33].

Although acquisition of knowledge is important, its application is closely related to the level of nurses' authority and self-confidence. A review of the data revealed the existence of a bilateral relationship among these three variables. These interactive relations among the three variables are highlighted in fig. 2. It is the total effect of these variables that brings a nurse the sense of professional power.

The majority of participants in this research considered a close relationship between power and the level of authority as well as self-confidence. Nurses frequently complained of lacking authority, but some participants implied that nurses have the authority to apply their professional knowledge but do not use it, due to some organizational and individual barriers.

Heavy workloads, staff shortage and unclear job descriptions were among the organizational barriers that made them become task-oriented and made them overlook their authority. Also, participants in this study complained of the lack of self-confidence and internalized dependency in nurses and considered it one of the leading causes of their powerlessness. To them, the wrong methods of education and frequent remonstrance and cross-examining of the nurses have played important roles in this regard. Laschinger et al. (2000), Nikbakht (2003) and Fulton (1997) also have reported that the nurses feel they have little formal and informal power and authority [34,19,10].

It seems that nurses have acquiesced to doctors' domination, and due to lack of self-confidence [35], the internalized beliefs about their own inferiority [18], low self-esteem, self-doubt and doubt in their own knowledge, ability [10], and competence [3], they have handed over the authority to those whom they consider superiors, and therefore give doctors the last word. But self-confident persons have an internal locus of control, and believe in their ability to influence results [36].

As fig. 2 indicates, there is an interactive relationship between the two variables of unification and being supported. According to participants in this research, these are the two variables that bring nurses collective power. It is through this type of power that nurses could secure better working conditions, professional independence and self-regulation. It is under such conditions that they could apply their professional knowledge in their caring practice and feel power.

As fig. 2 indicates, being supported is closely related to professional self-confidence and also to perceived authority. The participants also confirmed this, but they complained of the disunity and lack of group identity among nurses, as confirmed by Roberts (2000) [18].

It seems that some preoccupations of the nurses such as salary, income and job insecurity have caused them to remain in the first and second category of basic needs as described by Maslow, so that they lack the required motivation and ability for professional cooperation and progress. This situation has resulted in a lack of political and professional power, so that in spite of being the largest group in the health system, they are considered the weakest discipline [1,3].

Some authors have criticized nursing for concentrating on the personal elements of power and overlooking collective and political action. However, as Gilbert (1995) and Cheek and Rudge (1994) argue, it seems that nurses have gained a better awareness of the structure of power now, and have felt the need to change their sociopolitical actions [37,38]. As participants in this research implied, formation of professional unions and associations are the best strategies towards strengthening nursing as a profession. These organizations can provide a powerful support system for nurses and help them acquire better working conditions, but at the time of this research, Iranian nurses lacked it. In fact they expected their managers to support them.

As MacPhee and Scott (2002) argue, although not all the factors and working conditions are under the control of the managers, supporting the nurses can decrease current pressures on nurses to a considerable extent and increase the nurses' self-confidence and power [39]. Nurses expect their managers to provide them with facilities for care and financial and emotional support, so that they can take care of their patients with peace of mind [5].

When nurses are not provided with such support, they feel unable to control their working environment; thus they experience frustration, worthlessness and powerlessness. On the contrary, when they have such support, they feel power and authority [9,40,41] and have more confidence to act on their own diagnoses. It is here that Arai (1997) considers the existence of support and self-confidence as a must for the implementation of knowledge and skills [42].

Qualitative data such as emerged from this study need to be viewed from the immediate social and cultural milieu of the participants. It seems unlikely that only the workplace has affected nurses' power. There is much evidence of various power relationships in society that can have a negative effect on nurses' power and their effectiveness. Key areas such as childhood [43], gender [13,44] and class [13,45] are some of these factors.

Iranian society has a traditional, paternal and masculine culture, especially among the lower and middle classes, which emphasize obedience to the power holders, such as fathers (in the family), leaders and governors (in society), and managers and physicians (in the health system). Also, Iranian society traditionally has respected doctors and has seen nurses as doctors' assistants or handmaidens. Many physicians and hospital managers also regard nurses as doctors' helpers and do not consider them specialists in the art of caring [19]. These sociocultural factors also have played important roles in nurses' powerlessness and have decreased their self-esteem and prevent nurses from using their innate power and self-reliance [10].

Too, Iranian nurses lack a culture of teamwork, and although the participants in the study did emphasize the importance of unity and teamwork, the value of participative decision-making has not yet been realized. In Iranian culture, the person with the highest status makes the decisions; if the superior's wishes are clear, subordinates act in accordance with those wishes.

Recommendations

As data from this research indicated, organizational culture and its structure is the core variable that inhibits nurses' power. A review of existing organizational structure and communication strategies could help in balancing medical, nursing and administration input to strategic planning and decision-making. Managerial support; recognizing the value of nurses' services; mutual respect; implementing effective workforce planning; developing a system to ensure appropriate access to the resources required to meet client needs; providing staff with appropriate preparation, including continuing education, in order to deal effectively with increased public demand – all these can foster the professional and personal confidence and self-esteem of nurses. Management training and development programs to meet these needs are recommended.

Nurses appear to have some concerns and uncertainties about their scope of practice and the legal issues involved in their practice. Reviewing the nurses' job descriptions and providing continuing and accessible education about the scope of practice and practitioner accountability could decrease these concerns and encourage them to more empowered and independent practice.

Conclusions

The results of this study helped us to clarify the nurses' concept of power and its effective factors and strategies. Participants in this research considered power to be the "ability of a nurse to apply his/her knowledge and skills in the offering of nursing care based on his/her own judgment, in response to the needs of the clients."

Understanding this concept and removing the present barriers in the way of nurses can improve their power in offering quality care, and the effectiveness of the health system will be enhanced. The experiences of the participants proved the need to enhance nurses' "personal" and "collective" powers. Development of these powers depends on gaining and applying professional knowledge and skills. Delegating authority and enhancing self-confidence of nurses also help them apply their knowledge in practice.

The nurse managers can play an important role in supporting the nurses. This support can undertake any facilitating activity, such as providing facilities, means and equipment, information, education, rewards and even some symbolic behaviors that nurses perceive to be facilitating.

Although an extensive range of participants' views and experiences has been studied in this research, the small number of participants may limit the generalizability of the findings. Also, this study was conducted when nurses' morale was perhaps low because the government had recently started privatization of nursing, to which Iranian nurses were opposed. Additional research conducted with other populations of nurses will help us document nursing practice patterns and eventually to provide a pool of accumulated data related to factors affecting their professional power. This study was conducted in some of the biggest hospitals, and only in Tehran (the capital of Iran). Further research in other areas can give more information and deepen our knowledge in this regard. Also, further research is necessary to test hypotheses suggested by the model, such as the effect of unification and support on nurses' self-confidence and authority, as well as the interaction of the organizational structure and nurses' self-confidence in applying their professional knowledge.

Other research questions that might be helpful include the following:

• How do different types of organizational structure and administrative strategies influence nurses' professional power?

• What types of strategies could enhance nurses' self-confidence in their clinical practice?

• What type of changes in our educational system might be helpful in enhancing nurses' self-confidence in their clinical practice?

Answering these research questions would help us design strategies for empowering nurses to participate effectively in clinical practice by applying their professional knowledge and skills.

Appendix

A brief history of nursing in Iran

The development of nursing in Iran has been influenced by economic, historical, religious and cultural variables [46]. Until 70 years ago, nursing care of patients was carried out by women in the household or untrained personnel in hospitals [47]. In 1915 an American missionary endeavored to train a few nurses; after one year the same missionary established the first three-year nursing school in Tabriz, Iran. In 1935 the government obtained the services of three American nurse educators. They offered a two-year program in three nursing schools in three different cities. The graduates of these schools were called "doctors' assistants" because doctors had always been respected in Iranian society [47]. After that, more Western nurses, especially British nurses, continued to educate nurses in Iran, in two- to three-year programs, so nursing in Iran has been strongly influenced by British nursing tradition [19].

Before the Islamic revolution most nurses were women, but after the revolution, the nursing curriculum was reconstructed and more men entered the nursing profession. Now, nurses can study at universities from the level of a bachelor's degree to a PhD degree. At present 184 centers for nursing education offer the BSc degree, 12 centers offer the MSc degree [47] and six centers offer a PhD program in nursing. However, nursing in Iran still seen as a female occupation and nurses are seen as doctors' handmaidens in both the public and professional context [19].

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

MAH: Initiation and design of the research, collection and analysis of the data and writing the paper.

MS: Main supervision of the project, co-analysis of the data and editorial revision of draft papers.

FA: Supervision of the project and editorial revision of draft papers.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of all the nurses, nursing directors, supervisors, head nurses and physicians who participated in this research.

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the very helpful critiques of Dr Jane Salvage (Nursing and Midwifery Adviser, EIP/HRH, WHO headquarters). We are very grateful to Professor Ann H. White (University of Southern Indiana) for her helpful comments and linguistic revision of the manuscript; without her contribution the paper would not have been published.

Contributor Information

Mohsen Adib Hagbaghery, Email: adib1385@yahoo.com.

Mahvash Salsali, Email: m_salsali@hotmail.com.

Fazlollah Ahmadi, Email: fazlollaha@yahoo.com.

References

- World Health Organization Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery Services Geneva. 2002. http://www.wpro.who.int/themes_focuses/theme3/focus2/nursingmidwifery.pdf

- Wilkerson E. Lesson: Definitions & Philosophy of Nursing http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~erw/nur301/theory/philosophy/lesson.html

- O'Reilly P. Barriers to effective clinical decision making in nursing http://www.clininfo.health.nsw.gov.au/hospolic/stvincents/1993/a04.html

- Wilkinson G, Miers M. Power and Nursing Practice. London: Macmillan; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tomey MA. Guide to Nursing Management and Leadership. 6. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JR, Hartley CL. Managing and Coordinating Nursing Care. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robert J. Issues of empowerment for nurses and clients. Nursing Standard. 1997;11:44–46. doi: 10.7748/ns.11.46.44.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery Geneva. 2001. http://www.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA54/ea54r12.pdf

- Brown CL. A theory of the process of creating power in relationships. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2002;26:15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton Y. Nurses' views of empowerment: a critical social theory perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:529–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-13-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlinson M, Procter S. Efficiency and power: organizational economics meets organization theory. British Journal of Management . 1997;8:31–42. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.8.s1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough RA, Stewart RA. Power and control: social science perspectives. In: Richmond VP, McCroskey JC, editor. In Power in the Classroom: Communication, Control, and Concern. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins SR. Introduction to the special issue: defining gender, relationships, and power. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 2000;42:467–490. doi: 10.1023/A:1007010604246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin S. Occupational therapists and the concept of power: A review of the literature. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2001;48:24–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1630.2001.00231.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leksell JK, Johansson I, Wibell LB, Wikblad KF. Power and self-perceived health in blind diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;34:511–519. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H. Power and empowerment in nursing: three theoretical approaches. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31:235–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letvak S. Nurses as working women. AORN Journal. 2001;73:675–678. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SJ. Development of a positive professional identity: Liberating oneself from the oppressor within. Advances in Nursing Science. 2000;22:71–82. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikbakht NA, Emami A, Parsa YZ. Nursing experience in Iran. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9:78–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohansal S. Barriers to applying principles of management in wards of Tehran University on medical science hospitals: head nurses' viewpoints. Journal of Iranian Nurses and Midwives. 1994;8:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadian M. MSc thesis. Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Nursing; 1996. Correlation between stress and job satisfaction in critical care nurses in hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, in year 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Postmodern nursing and beyond. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon N. Grounded Theory: theoretical background. In: Richardson JTE, editor. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for Psychology and the Social Sciences. London: The British Psychological Society Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Backman K, Kyngas HA. Challenges of the grounded theory approach to a novice researcher. Nursing and Health Sciences. 1999;1:147–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.1999.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editor. In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 158–183. [Google Scholar]

- Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing, Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Hungler BP. Essentials of nursing research, methods, appraisal, and utilization. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier D, Duffield C, Mitten-Lewis S, Crisp J, Nagy S, Adams A. Australian nurse educators identify gaps in expert practice. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2000;31:224–234. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-20000901-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed NV. Power, its use and potential for misuse by nurse consultants. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2001;15:177–181. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200107000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H. The qualities of an empowered nurse and the factors involved. J Nurs Manag. 2001;9:273–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2001.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubsch SM. Conflict, enactment, empowerment: conditions of independent therapeutic nursing intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb03152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P, Tanner C, Chesla C. Expertise in Nursing Practice: Caring, Clinical Judgment and Ethics. New York: Springer Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS, Fingan J, Shamian J, Casier S. Organizational trust and empowerment in registered healthcare settings: effects on staff nurse commitment. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2000;30:413–425. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madjar I, McMillan M, Sharkey R, Cadd A. Project to review and examine expectations of beginning registered nurses in the workforce 1997. Research project The University of Newcastle. 1997. http://www.nursesreg.nsw.gov.au/exp_brns.pdf

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert T. Nursing: empowerment and the problem of power. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;21:865–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21050865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J, Rudge T. Nursing as a textually mediated reality. Nursing Inquiry. 1994;1:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.1994.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee M, Scott J. The role of social support networks for rural hospital nurses: supporting and sustaining the rural nursing work force. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2002;32:264–272. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East FJ. Empowerment through welfare-rights organizing: A feminist perspective. Nursing Administration. 2000;15:311–328. doi: 10.1177/08861090022093886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS, Finegan J, Shaman J. Promoting nurses' health: Effect of empowerment on job strain and work satisfaction. Nursing Economics. 2001;19:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arai SM. Empowerment: from the theoretical to the personal. Journal of Leisurability. 1997;24 http://www.lin.ca/resource/html/Vol24/v24n1a2.htm [Google Scholar]

- Heron J. Feeling and Personhood: Psychology in Another Key. London: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zelek B, Phillips SP. Gender and power: nurses and doctors in Canada. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2003;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E. Critical Psychology and Pedagogy: Interpretation of the Personal World. New York: Bergin & Garvey Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Salsali M. Nursing and nursing education in Iran. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1999;31:190–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsali M. The development of nursing education in Iran. International History of Nursing Journal. 2000;5:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]