Abstract

CBX7 is a polycomb protein that participates in the formation of polycomb repressive complex 1. Apart from few exceptions, CBX7 expression is lost in human malignant neoplasias and a clear correlation between its downregulated expression and a cancer aggressiveness and poor prognosis has been observed. These findings indicate a critical role of CBX7 in cancer progression. Consistently, CBX7 is able to differentially regulate crucial genes involved in cancer progression and in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, as osteopontin and E-cadherin. Recent evidences indicate a role of CBX7 also in the modulation of response to therapy. In conclusion, CBX7 represents an important prognostic factor, whose loss of expression in general indicates a bad prognosis and a progression towards a fully malignant phenotype.

Keywords: CBX7, cancer progression, polycomb group

CBX7 and the polycomb group proteins

CBX7 belongs to the family of Chromobox proteins and takes part in the organization of the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1). Proteins of the polycomb group (PcG) operate in the context of multiprotein complexes that are involved in the regulatory mechanism controlling cell fate during development, in both normal and pathogenic conditions, through the silencing of development-related genes. Indeed, PcG proteins cooperate to establish transcriptional repressor elements of at least two functionally distinct complexes: (a) the initiation complex (PRC2), whose main principal elements are human EZH2, EED and SUZ12, and (b) the maintenance complex (PRC1), containing as central human proteins BMI1, CBX7, EDR, HPC and RNF2 [1-3]. In the PRC2 complex, EZH2 carries-on methyltransferase activity on histone lysine residues (histone H3, trimethylation of lysine 27, H3K27me3), that is essential for inducing transcriptional repression and stable gene silencing. On the contrary, CBX7 is able to bind H3K27me3 sites, through the chromodomain, then controlling the expression of multiple genes [1-3].

Alterations of this crucial PcG system are responsible of aberrant development programs and developing of different types of carcinoma. In fact, abnormal increased expression of either PRC1 or PRC2 triggers the aberrant silencing of corresponding target genes, finally leading to the appearance of a broad spectrum of carcinomas [4,5]. However, also the recruitment of PcG complexes to genes, normally not under their control, can induce formation of cancers. In fact, it has been recently reported that the oncogenic transcription factor PML/RAR alpha is able to recruit the PRC2 complex to genes responsive to retinoic acid (RA), then playing a primary role in the development of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) [6].

Aberrant expression of CBX7 in human carcinomas

Expression levels of CBX7 have been found decreased in most of the human malignant neoplasias analyzed so far. CBX7 downregulation was initially reported in carcinomas of the bladder: the expression analysis performed in 93 patients undergoing surgery for urothelial carcinoma revealed that expression levels of CBX7 mRNA gradually decreased going from superficial to invasive and, lastly, to muscle-invasive carcinomas [7]. Besides, the expression levels of CBX7 resulted significantly correlated with higher tumor grade, suggesting that decreased levels of CBX7 could be functionally related with the acquisition of an aggressive phenotype in urothelial carcinomas [7]. Similar findings were obtained when CBX7 expression levels were evaluated in thyroid [8], colorectal [9], breast [10], pancreas [11], lung carcinomas [12] and glioblastoma [13].

In human thyroid carcinoma, CBX7 expression levels, evaluated by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry, progressively declined with the loss of differentiation degree and increasing of neoplasia stage. In fact, CBX7 was quite abundant in normal thyroid cells, whereas it was almost undetectable in most of the undifferentiated anaplastic carcinoma (ATC) and present, but at lower levels with respect to normal thyroid, in well differentiated ones as papillary (PTC) and follicular (FTC) carcinomas [8]. CBX7 was found decreased or absent in 68% of Hürthle adenomas, which are characterized by an aggressive phenotype if compared to the classic benign follicular adenomas (FTA) [14]. Interestingly, expression of CBX7 in Hürthle hyperplasias and FTA resulted comparable to that observed in non pathological thyroid tissue, confirming the more aggressive phenotype of Hürthle adenomas in comparison to non-Hürthle neoplasias [14]. In addition, loss of heterozygosity at CBX7 locus occurred in 36.8% of PTC and in 68.7% of ATC. Moreover, the evaluation of CBX7 expression in rat and mouse models of thyroid carcinogenesis confirmed that CBX7 decreased with the malignancy of carcinomas. Indeed, CBX7 diminished in PTC developed by TRK and RET/PTC3 transgenic mice, while was completely lacking in ATC developed by SV40 Large T mice [8].

The immunohistochemical analysis of a tissue microarray (TMA) containing more than one thousand sporadic CRC lesions revealed that CBX7 is also decreased or absent in a high number of CRC samples, in comparison to the non pathological colonic mucosa, and that the loss of expression was correlated with poor prognosis [9]. Interestingly, CBX7 downregulation was also associated with progression of dysplasia since levels of CBX7 expression decreased as severity of dysplasia increased [9]. Noteworthy, HMGA1 expression, that has been frequently reported associated to cancer progression, increases going from colonic pre-malignant lesions to colonic carcinoma, with a mutual behavior if compared to CBX7 [15,16].

Similarly, a progressive decrease of CBX7 protein expression was observed in specific neoplastic malignancies of pancreas [11]. In this system, as observed in other carcinomas, the diminished expression of CBX7 resulted interconnected with progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, being its expression abundant in normal pancreatic tissue and progressively decreased going from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs) through invasive ductal carcinoma, where CBX7 expression is completely lost [11]. Consistently, the retention of CBX7 expression displayed a trend toward a better survival.

As far as human lung carcinoma is concerned, none of the samples analyzed expressed detectable quantity of CBX7 protein, whereas it was abundantly expressed in normal lung tissue. Interestingly, LOH was reported in 50% of informative cases. Additionally, the expression of CBX7 was lost in the “normal” area surrounding carcinomas (non-pathological at the morphological evaluation) in 50% of the analyzed cases. Intriguingly, these cases showed also LOH, suggesting that the decreased expression of CBX7 could be involved in the transition of epithelial lung cells toward a fully transformed and malignant phenotype [12].

Reduced CBX7 protein levels were also observed in breast carcinomas with the lowest expression levels observed in the lobular histotype [10]. The expression of CBX7 was also downregulated in most of the gastric and liver carcinomas [17].

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, cancergenome.nih.gov) shows that several PcG members are aberrantly expressed in glioblastoma multiforme samples in comparison to normal brain, with the upregulation of CBX8, EZH2, PHC2 and PHF19, and downregulation of CBX6, CBX7, EZH1 and RYBP. Intriguingly, decreasing of CBX7 levels progressively occurred with the increasing of astrocytoma grade, as assessed by Western blot and RT-PCR analyses [13]. Lastly, consulting of TCGA confirms that CBX7 is generally underexpressed in various carcinoma tissues (central nervous system cancer, colorectal, ALL, hepatocarcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, melanoma and sarcoma) if compared with corresponding normal ones. In addition, CBX7 is expressed at higher levels in ER+ than ER- breast cancer and at lower levels in metastatic prostate cancer than primary ones (TCGA, cancergenome.nih.gov). These results, therefore, associate the loss of CBX7 expression with cancer progression and poor prognosis, proposing for CBX7 a tumor suppressor role that is also supported by the negative effect on cell growth exerted by the restoration of CBX7 expression in thyroid [8], breast [10] and colorectal cancer cells [9].

The generation of cbx7 knock-out (ko) mice further confirmed its tumor suppressor role. In fact, cbx7 ko mice developed lung and liver neoplasias, either adenoma or carcinoma. While, the same percentage of liver benign lesions were shown by cbx7 -/- (homozygous) and cbx7 -/- (heterozygous) mice, a higher percentage of hepatocellular carcinomas was observed in cbx7 -/- versus cbx7 -/- mice. In addition, lung adenomas and adenocarcinomas occurred in cbx7 -/- and cbx7 -/- mice, though adenomas were mainly detected in cbx7 -/-, whereas carcinomas were prevalent in cbx7 -/- mice [12]. Consistently, cbx7 -/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) grow faster than the cbx7 +/+ (wild type) counterparts, with a lower percentage of cbx7 -/- MEFs in G1 and a higher one in S phase of the cell cycle, in comparison with cbx7 +/+ MEFs, suggesting a negative modulation of the cell cycle due to cbx7 in the G1/S phases [12]. In addition, the absence of cbx7 expression limited the susceptibility of cbx7 -/- MEFs to undergo senescence. Accordingly, cbx7 -/- MEFs showed lower levels of p16, p53 and p21 if compared with cbx7 +/+ MEFs and elevated levels of both Cyclin A and Cyclin E [12]. Cbx7 -/- mice displayed a considerable increase in body length if compared to the wt mice [18] and, unexpectedly, an abundant accumulation of fat tissue suggesting a role of cbx7 in adipogenesis, too. This hypothesis has been confirmed in cbx7 -/- MEFs that are more efficiently committed to differentiate towards adipocytic phenotype in comparison to the cbx7 +/+ MEFs, with global effect depending on the cbx7 dosage [18]. Intriguingly, similar results have been observed in cbx7-/- embryonic stem (ES) cells as far as is concerned the differentiation into adipocytes, whereas MEFs and human adipose-derived stem cells overexpressing CBX7 showed an opposite behavior [18].

Regulation of CBX7 protein expression

A critical role in regulating CBX7 expression is played by the High Mobility Group A (HMGA) proteins. The HMGA protein family consists of three proteins (HMGA1a, HMGA1b and HMGA2) able to bind DNA in AT-rich sites, but lacking transcriptional activity per se. Nevertheless, they are able to positively or negatively modulate the transcriptional activity of several gene promoters by interacting with multiple partners of the transcriptional apparatus, and consequently, altering chromatin structure [19]. In non-pathological cells and tissues HMGA proteins are not expressed, but their levels are extremely high in malignant neoplasias, also representing a poor prognostic index [19]. Therefore, HMGA protein expression has opposite implications with respect to CBX7.

It has been reported that the silencing of HMGA1 expression leads to increased CBX7 mRNA and protein expression levels [10] and that HMGA1 overexpression has an opposite effect on CBX7 expression. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments have shown that HMGA1 proteins directly bind CBX7 promoter, thereby negatively modulating its transcriptional activity [10]. Additionally, in breast carcinomas it has been observed an inverse correlation between the levels of CBX7 and HMGA1, confirming that HMGA1 is also able to negatively affect the expression of CBX7 in vivo [10].

Albeit other consistent studies concerning the transcriptional regulation of CBX7 are lacking, several interesting works based on microRNA (miRNA) investigations suggest remarkable mechanisms controlling CBX7 protein levels [20]. MiRNAs represent a novel group of regulatory molecules that modulate gene expression by acting at post-transcriptional level. They are small RNA molecules constituted by 19-22 bp that are able to bind to the 3’-UTR of mRNA transcripts, triggering their direct cleavage or repressing their translation [20,21].

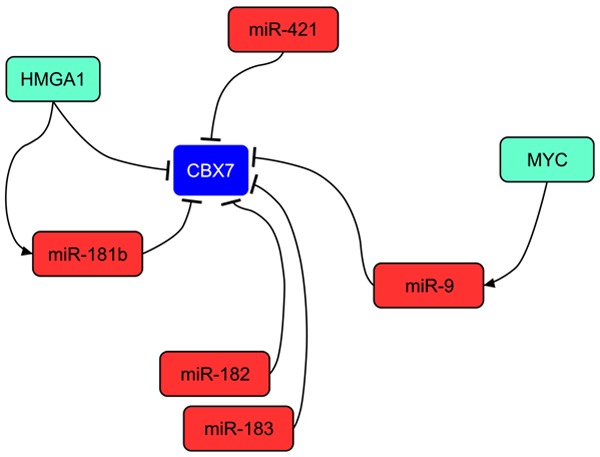

It has been demonstrated that some miRNAs are able to modulate CBX7 protein expression levels (Figure 1). Indeed, miR-181a and miR-181b are able to contact two corresponding binding sites in the 3’-UTR of CBX7 and experimental evidences reported that its expression levels resulted affected by this regulation. Consistently with these observations, reciprocal experiments aimed at knocking down miR-181 levels in breast carcinoma cells demonstrated an increase of CBX7 protein levels with consequent accumulation of cancer cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle [10]. Intriguingly, both miR-181a and miR-181b are transcriptionally repressed by CBX7 in a dose-dependent fashion. Indeed, cbx7 -/- MEFs showed higher levels of these miRNAs in comparison to cbx7 +/+ MEFs, whereas cbx7 -/- MEFs expressed intermediate levels [10]. Therefore, if on one hand CBX7 is able to negatively regulate the expression of miR-181, on the other hand it is subjected to a double negative regulation due to miR-181 itself and the HMGA1 protein, highly expressed in breast carcinomas and able to induce the expression of miR-181 [10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms leading the loss of CBX7 expression in human cancers. Several miRNAs are involved in the repression of CBX7 expression. In particular, HMGA1 protein exerts a double negative control directly on CBX7 promoter and indirectly by inducing the expression of miR-181b.

Additionally, in breast carcinomas, the knock-down of miR-182 and miR-183, highly expressed in this cancer, increased the levels of CBX7 demonstrating that CBX7 is also targeted by these two miRNAs [22]. Moreover, the inhibition of miR-421, highly expressed in gastric carcinomas, leads to the increase of CBX7 levels and to a decrease of growth rate of gastric carcinoma cells [23]. Finally, it is worth noting that miR-9 has also been reported to downregulate the expression of CBX7 in gliomas [24] (Figure 1).

Mechanism by which the loss of CBX7 expression contributes to cancer progression

One of the main effects of the loss of CBX7 expression is the consequent reduction or loss of E-cadherin expression that plays an important role in maintaining the epithelial phenotype, its loss or decreased expression leading to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [25,26]. It has been reported that CBX7 is able to sustain the expression of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1) by binding its promoter and counteracting the anti-transcriptional effect of histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) [27]. In this mechanism CBX7 plays a central role since the block of HDAC2 activity exerted by the interaction with CBX7 triggers the acetylation of CDH1 gene promoter and the subsequent methylation of particular sites of H3 and H4 histones [27]. This modulates the histone code in the promoter region, finally promoting the transcriptional activity of CDH1 gene. The associated expression between CBX7 and E-cadherin has been observed not only in thyroid carcinomas, in particular in the anaplastic phenotype [27], but also in pancreatic carcinomas [11], where a particular association has been also found with patient survival. These findings suggest, therefore, that CBX7 might play a fundamental role during the progression of pancreatic carcinomas [11].

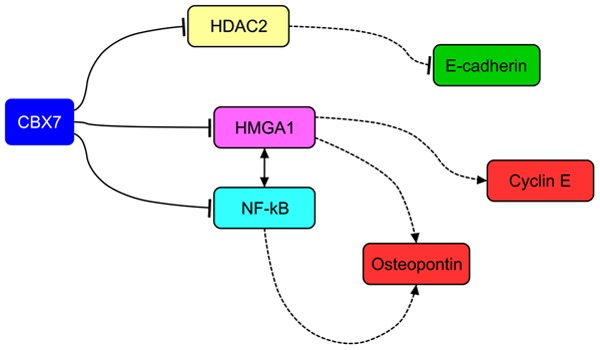

However, other mechanisms participating in the EMT regulation cooperate with CBX7 in the regulation of E-cadherin. Indeed, miR-9, that has CBX7 as target and is activated by MYC, is able to negatively regulate the expression of E-cadherin protein in breast cancer cells, resulting in increased migration and invasiveness of breast cancer cells, with the formation of cancer metastases [28]. This allows envisaging a superior regulatory mechanism able to trigger EMT, starting from MYC and HMGA1 and culminating in the complete loss of E-cadherin expression, through the regulation of miR-9 and CBX7 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of cell transformation involving CBX7. CBX7 prevents cell transformation by sustaining E-cadherin expression and repressing Cyclin E and Osteopontin expression, through a mechanism involving the interaction with HDAC2 and HMGA1, respectively. Dashed lines indicate loss of regulatory action.

CBX7 is able to negatively regulate the expression of genes that positively induce epithelial cells to undergo EMT. In fact, CBX7 is able to negatively regulate the expression of SPP1 gene [29], whose protein product (osteopontin) has been widely and causally associated with cell migration/invasion and with the acquisition of a highly malignant phenotype [30-32]. In this case, it has been observed that the mechanism of osteopontin regulation relies on the ability of CBX7 to counteract the positive effect due to HMGA1b protein that exerts a positive transcriptional regulation on the SPP1 promoter. CBX7 competes with HMGA1b for the binding to SPP1 promoter and their relative expression balance is likely to differentially modulate the osteopontin expression. However, in this mechanism CBX7 and HMGA1b do not represent the unique partners of interactions. Indeed, the NF-kB complex represents a central positive regulator of osteopontin expression [33] and its presence on SPP1 promoter allows a fine tuning of osteopontin expression, since CBX7 tends again to repress its activity, whereas HMGA1b potentiates its function [29] (Figure 2).

CBX7, likely due to its ability to bind chromatin in multiple regions of the promoter of cancer-related genes, displays its ability not only in the regulation of EMT-related genes, but also in the regulation of cell cycle and proliferation genes [12]. In fact, it has been reported that the loss of cbx7 in ko mouse model system triggers an intense expression of Cyclin E expression and this is mainly due to the presence of HMGA1b. In fact, as reported for SPP1 gene, also on the promoter of CCNE gene HMGA1b is able to exert a positive transcriptional regulation that, conversely, is counteracted by CBX7 [12]. Indeed, in this mechanism, the binding of CBX7 to the CCNE promoter keeps HDAC2 on site, maintaining the deacetylation of promoter and blocking the transcription. The presence of abundant HMGA1b protein and/or the reduction of CBX7 allows HMGA1b itself to displace CBX7 and HDAC2, with the consequent acetylation and fully activation of the CCNE promoter [12] (Figure 2).

Recently, it has been also demonstrated that CBX7 is able to differently modulate the expression of crucial genes involved in cancer progression [34]. Among the set of CBX7 downregulated genes other than SPP1 worth of noting are SPINK1 and STEAP1, encoding proteins overexpressed in several human carcinomas. Among the genes positively regulated by CBX7, there are FOS, FOSB and EGR1. The first two genes are members of the transcriptional complex AP-1, for which now are emerging new findings indicating them as tumor suppressor genes in particular context, while EGR1 is a DNA-binding protein with transcriptional activity [34]. CBX7 has been found to directly bind and regulate the activity of these promoters and these results suggest that regulatory mechanisms exerted by CBX7 are more complex than they appear, since CBX7 itself is able to modulate the expression of other transcription factors, that could be part of the same regulatory machinery [34]. This observation has been further corroborated by the finding that the expression of CBX7 and its regulated genes are closely related either in thyroid and in lung carcinomas [34].

CBX7 as oncogene

Even though all the reported studies seem to emphasize an oncosuppressor role for CBX7, other studies report CBX7 overexpression in some malignancies, suggesting CBX7 to act as an oncogene. It has been shown that CBX7 is highly expressed in three prostate cancer cell lines and its suppression through the use of short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) caused the upregulation of p16Ink4a and p14Arf, with the consequent block of cell growth in LNCaP and PC-3 cells, directly depending on the p14Arf/p53 and p16Ink4a/Rb pathways. On the other hand, the enforced expression of CBX7 in LNCaP cells conferred only a slight advantage to cell growth either in androgen-dependent and -independent conditions [35]. Moreover, it has been reported that CBX7 cooperates with c-Myc to make LNCaP cells not sensitive to growth arrest due to the block of androgen receptor [35]. However, since in this study an intense expression of CBX7 in the normal prostatic tissue has been also reported and TCGA reports a decreased CBX7 expression in metastatic prostate cancer, further studies are required to assess CBX7 overexpression in prostatic carcinoma tissues.

CBX7 has been recently shown to be overexpressed in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma, a cancer histotype displaying a relative poor prognosis among the different ovarian neoplasias [36]. Patients overexpressing CBX7 showed reduced overall and progression-free survival rates, in comparison with patients not expressing CBX7. Accordingly, the silencing of CBX7 expression in two ovarian carcinoma cell lines negatively affected their cell viability, inducing expression of the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [36].

Furthermore, the specific targeting of cbx7 expression in the mouse lymphoid compartment was sufficient to trigger T cell lymphomagenesis and to induce the formation of aggressive B-cell lymphomas, in cooperation with c-Myc [1]. It is reasonable that the oncogenic or tumor suppressor activity might depend on the cellular context since, in different kind of cells, CBX7 may interact with different partners silencing or activating distinctive set of genes.

Consistently with an oncogenic role, CBX7 prolongs the lifespan of different human primary cells, also immortalizing mouse fibroblasts through the repression of the Ink4a/Arf locus [37]. CBX7 expression levels are decreased throughout replicative senescence and its silencing by using shRNA treatment impaired growth properties of normal cells, through the unlocking of the Ink4a/Arf locus [37]. In one study it was shown that CBX7 was able to extend cellular lifespan and increase proliferation rate [37], but it was also demonstrated that cbx7 -/- MEFs were less susceptible to undergo senescence and displayed faster growth rate in comparison with cbx7 +/+ MEFs [12]. In general, distinctive experimental methodologies, in vitro or in vivo, may likely explain discrepancies in the obtained results. In fact, according to this hypothesis, a previous work regarding the p53 pathway reported significant divergences between in vivo model and in vitro transfection results [38]. It is likely that current transfection protocols are not adequate to faithfully reproduce the relative proportions between CBX7, interacting partners and regulators.

Conclusions and perspectives

In spite of the controversial role of CBX7 in cancer progression and the requirement of additional studies to fully comprehend the full spectrum of CBX7 activities, the majority of the studies report the loss of CBX7 expression in most of the human malignant neoplasias analyzed, highlighting a clear correlation with poor prognosis. Moreover, the anti-oncogenic role of CBX7 seems to be validated by its ability to counteract the oncogenic role of the HMGA proteins and to block the expression of genes critically relevant for proliferation and migration (CCNE and SPP1).

All these results suggest that CBX7 downregulation could represent a crucial event during cancer progression, proposing the evaluation of CBX7 in the same way as other important prognostic markers, particularly if associated with the evaluation of other genes, such as HMGA1, or miRNAs functionally associated, such as miR-181. Of course, in the case of ovarian carcinomas the overexpression of CBX7 has to be considered a negative predictor of prognosis.

Preliminary studies are proposing a role for CBX7 in the regulation of apoptosis and chemosensitivity. Indeed, CBX7 would prevent the expression of several miRNAs able to target apoptosis-related genes, such as TRAIL and Bcl-2, further supporting the critical role of its loss during cancer progression. Furthermore, the expression of CBX7 would be able to increase the sensitivity of lung carcinoma cells to irinotecan (unpublished observations).

In conclusion, additional studies aimed at characterizing the activity of CBX7 in the modulation of cancer cell sensitivity to novel antineoplastic drugs might support the establishment of a more accurate and specific personalized therapy based on the levels of CBX7 expression.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this review has been supported by grants from: PNR-CNR Aging Program 2012-2014, POR Campania FSE 2007-2013 (CREMe), CNR Flagship Projects (Epigenomics-EPIGEN, Nanomax-DESIRED), PON 01-02782 (Nuove strategie nanotecnologiche per la messa a punto di farmaci e presidi diagnostici diretti verso cellule cancerose circolanti), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC IG 11477). We thank PathVisio developers for the opportunity to use the open-source drawing software tool [39].

References

- 1.Scott CL, Gil J, Hernando E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Narita M, Martinez D, Visakorpi T, Mu D, Cordon-Cardo C, Peters G, Beach D, Lowe SW. Role of the chromobox protein CBX7 in lymphomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5389–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuettengruber B, Chourrout D, Vervoort M, Leblanc B, Cavalli G. Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell. 2007;128:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JI, Lessard J, Crabtree GR. Understanding the words of chromatin regulation. Cell. 2009;136:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajasekhar VK, Begemann M. Concise review: roles of polycomb group proteins in development and disease: a stem cell perspective. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2498–2510. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villa R, Pasini D, Gutierrez A, Morey L, Occhionorelli M, Vire E, Nomdedeu JF, Jenuwein T, Pelicci PG, Minucci S, Fuks F, Helin K, Di Croce L. Role of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinz S, Kempkensteffen C, Christoph F, Krause H, Schrader M, Schostak M, Miller K, Weikert S. Expression parameters of the polycomb group proteins BMI1, SUZ12, RING1 and CBX7 in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and their prognostic relevance. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:323–329. doi: 10.1159/000170879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pallante P, Federico A, Berlingieri MT, Bianco M, Ferraro A, Forzati F, Iaccarino A, Russo M, Pierantoni GM, Leone V, Sacchetti S, Troncone G, Santoro M, Fusco A. Loss of the CBX7 gene expression correlates with a highly malignant phenotype in thyroid cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6770–6778. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallante P, Terracciano L, Carafa V, Schneider S, Zlobec I, Lugli A, Bianco M, Ferraro A, Sacchetti S, Troncone G, Fusco A, Tornillo L. The loss of the CBX7 gene expression represents an adverse prognostic marker for survival of colon carcinoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2304–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansueto G, Forzati F, Ferraro A, Pallante P, Bianco M, Esposito F, Iaccarino A, Troncone G, Fusco A. Identification of a New Pathway for Tumor Progression: MicroRNA-181b Up-Regulation and CBX7 Down-Regulation by HMGA1 Protein. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:210–224. doi: 10.1177/1947601910366860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karamitopoulou E, Pallante P, Zlobec I, Tornillo L, Carafa V, Schaffner T, Borner M, Diamantis I, Esposito F, Brunner T, Zimmermann A, Federico A, Terracciano L, Fusco A. Loss of the CBX7 protein expression correlates with a more aggressive phenotype in pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1438–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forzati F, Federico A, Pallante P, Abbate A, Esposito F, Malapelle U, Sepe R, Palma G, Troncone G, Scarfo M, Arra C, Fedele M, Fusco A. CBX7 is a tumor suppressor in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:612–623. doi: 10.1172/JCI58620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Warden C, Zou Z, Neman J, Krueger JS, Jain A, Jandial R, Chen M. Altered expression of polycomb group genes in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monaco M, Chiappetta G, Aiello C, Federico A, Sepe R, Russo D, Fusco A, Pallante P. CBX7 Expression in Oncocytic Thyroid Neoplastic Lesions (Hürthle Cell Adenomas and Carcinomas) Eur Thyroid J. 2014;3:211–216. doi: 10.1159/000367989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abe N, Watanabe T, Sugiyama M, Uchimura H, Chiappetta G, Fusco A, Atomi Y. Determination of high mobility group I(Y) expression level in colorectal neoplasias: a potential diagnostic marker. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1169–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiappetta G, Manfioletti G, Pentimalli F, Abe N, Di Bonito M, Vento MT, Giuliano A, Fedele M, Viglietto G, Santoro M, Watanabe T, Giancotti V, Fusco A. High mobility group HMGI(Y) protein expression in human colorectal hyperplastic and neoplastic diseases. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:147–151. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1033>3.3.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan ZP, Gu LK, Xing BC, Ji JF, Gu J, Deng DJ. [Downregulation of chromobox protein homolog 7 expression in multiple human cancer tissues] . Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;45:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forzati F, Federico A, Pallante P, Colamaio M, Esposito F, Sepe R, Gargiulo S, Luciano A, Arra C, Palma G, Bon G, Bucher S, Falcioni R, Brunetti A, Battista S, Fedele M, Fusco A. CBX7 gene expression plays a negative role in adipocyte cell growth and differentiation. Biol Open. 2014;3:871–879. doi: 10.1242/bio.20147872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fusco A, Fedele M. Roles of HMGA proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrc2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pallante P, Battista S, Pierantoni GM, Fusco A. Deregulation of microRNA expression in thyroid neoplasias. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:88–101. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannafon BN, Sebastiani P, de las Morenas A, Lu J, Rosenberg CL. Expression of microRNA and their gene targets are dysregulated in preinvasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Z, Guo J, Xiao B, Miao Y, Huang R, Li D, Zhang Y. Increased expression of miR-421 in human gastric carcinoma and its clinical association. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao TF, Zhang Y, Yan XQ, Yin B, Gong YH, Yuan JG, Qiang BQ, Peng XZ. [MiR-9 regulates the expression of CBX7 in human glioma] . Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2008;30:268–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:131–142. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federico A, Pallante P, Bianco M, Ferraro A, Esposito F, Monti M, Cozzolino M, Keller S, Fedele M, Leone V, Troncone G, Chiariotti L, Pucci P, Fusco A. Chromobox protein homologue 7 protein, with decreased expression in human carcinomas, positively regulates E-cadherin expression by interacting with the histone deacetylase 2 protein. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7079–7087. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma L, Young J, Prabhala H, Pan E, Mestdagh P, Muth D, Teruya-Feldstein J, Reinhardt F, Onder TT, Valastyan S, Westermann F, Speleman F, Vandesompele J, Weinberg RA. miR-9, a MYC/MYCN-activated microRNA, regulates E-cadherin and cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sepe R, Formisano U, Federico A, Forzati F, Bastos AU, D’Angelo D, Cacciola NA, Fusco A, Pallante P. CBX7 and HMGA1b proteins act in opposite way on the regulation of the SPP1 gene expression. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2680–92. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matusan K, Dordevic G, Stipic D, Mozetic V, Lucin K. Osteopontin expression correlates with prognostic variables and survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:325–331. doi: 10.1002/jso.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuck AB, Chambers AF, Allan AL. Osteopontin overexpression in breast cancer: knowledge gained and possible implications for clinical management. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:859–868. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohde F, Rimkus C, Friederichs J, Rosenberg R, Marthen C, Doll D, Holzmann B, Siewert JR, Janssen KP. Expression of osteopontin, a target gene of de-regulated Wnt signaling, predicts survival in colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1717–1723. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berge G, Pettersen S, Grotterod I, Bettum IJ, Boye K, Maelandsmo GM. Osteopontin--an important downstream effector of S100A4-mediated invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:780–790. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallante P, Sepe R, Federico A, Forzati F, Bianco M, Fusco A. CBX7 modulates the expression of genes critical for cancer progression. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernard D, Martinez-Leal JF, Rizzo S, Martinez D, Hudson D, Visakorpi T, Peters G, Carnero A, Beach D, Gil J. CBX7 controls the growth of normal and tumor-derived prostate cells by repressing the Ink4a/Arf locus. Oncogene. 2005;24:5543–5551. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinjo K, Yamashita Y, Yamamoto E, Akatsuka S, Uno N, Kamiya A, Niimi K, Sakaguchi Y, Nagasaka T, Takahashi T, Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Kikkawa F, Toyokuni S. Expression of chromobox homolog 7 (CBX7) is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma via TRAIL-induced apoptotic pathway regulation. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:308–318. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil J, Bernard D, Martinez D, Beach D. Polycomb CBX7 has a unifying role in cellular lifespan. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:67–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Iersel MP, Kelder T, Pico AR, Hanspers K, Coort S, Conklin BR, Evelo C. Presenting and exploring biological pathways with PathVisio. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]