Abstract

Bcl-xL/Bcl-2-associated death promoter (Bad) is a proapoptotic member of Bcl-2 family and plays a key role in tumor development. To explore the expression of Bad and its clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), we analyzed a large cohort of 437 HCC samples by tissue microarray (TMA)-based immunohistochemistry. Our data showed that Bad expression was markedly decreased in 50.6% (221/437) of HCC tissues, compared with the adjacent nontumorous tissues. Bad expression was closely associated with adverse clinical characters such as clinical stage (P=0.007), tumor size (P=0.008), vascular invasion (P=0.024), tumor differentiation (P=0.018) and AFP level (P=0.039). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that low Bad expression was significantly correlated to overall survival (P<0.0001) but not disease-free survival (P=0.587) and recurrence-free survival (P=0.707) of patients with HCC. Stratified survival analysis further confirmed the prognostic value of Bad. Moreover, multivariate analyses revealed that Bad was an independent indicator of overall survival in HCC (hazard ration=0.589, 95% confidence interval: 0.483-0.717, P<0.0001). Collectively, our data suggest that Bad is down-regulated in HCC and serves as a promising biomarker for poor prognosis of patients with this fatal disease.

Keywords: Bad, BCL-2, poor prognosis, hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer mortality [1]. Although surgical technique and anticancer drugs for target treatment of HCC have been improved, the overall survival (OS) rate remains low and the occurrence of postoperative relapse or metastasis remains high in patients with HCC [2,3]. Lots of evidence showed that the loss of sensitivity to apoptosis is a potential mechanism of HCC invasion, metastasis and failing response to drug treatment [4,5]. The sequential accumulation of genetic/epigenetic abnormalities of HCC endows the ability to escape the death mediated by apoptosis in which Bcl-2 family proteins play a key role [6,7]. However, the expression of several Bcl-2 family proteins remains unclear in HCC. In particular, rare is known about the expression and clinical significance of Bad, a member of the BH3-only family proteins.

Bad characters as a pro-apoptotic protein and plays a crucial role in connecting the cell survival signaling pathway and apoptosis signaling pathway. Bad has been identified as a critical element of several anti-apoptotic signaling pathways in many types of cancer including colon, prostate and breast cancer [8-10]. The activity of Bad is primarily mediated by its conserved phosphorylation sites including serines 112, 136 and 155. Phosphorylated Bad fails to bind Bcl-xl or Bcl-2 proteins [11,12]. Previous reports demonstrated that Bad was dephosphorylated to exert its lethal function [13,14]. On the other hand, a large number of studies suggest Bad expression as a strong predictor of overall survival in many cancers. Cekanova M et al. demonstrated that Bad was down-regulated in breast cancer tissues and inhibited tumor invasion and migration [15]. Al-Bazz et al. reported that patients with high expression of Bad had a longer overall survival and disease-free survival [16]. Huang Y et al. showed that low expression of Bad was associated with shorter survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [17]. The prognostic value of Bad was also studied in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [18]. In HCC, Bad has been identified as a potential therapeutic target and plays a key role in cell apoptosis, responding to sorafenib treatment [19]. However, the expression of Bad and its clinical significance in HCC remains elusive.

In this study, the expression of Bad in 437 HCC patients was examined by tissue microarray (TMA)-based immunohistochemistry. Relationship between Bad expression and the clinicopathological features was assessed and the prognostic value of Bad in HCC was further determined.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue specimens

All specimens along with complete clinical and pathological data were obtained from 437 HCC patients who underwent surgical resection at Sun Yat-sen university cancer center, between January 2000 and December 2010. Eight paired HCC and corresponding adjacent nontumorous tissues after surgical resection immediately stored at -80°C were subjected to western blot. The 437 patients aged from 13 to 68 years (median age is 49). Tumor stage was defined according to tumor-node metastasis (TNM) classification of the American Joint Committee on International Union against Cancer. Tumor differentiation was assessed according to Edmonson and Steiner grading system. The use of tissues for this study has been approved by the Institute Research Medical Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen university cancer center.

Western blot

Western blot was performed to detect the expression level of Bad protein in HCC tissues. Tissues were collected and lysed with lysis buffer (pH 7.4, containing 1% Triton X-100 and 0.2% SDS). Then cell lysates were kept on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was separated and was stored in -80°C until required for the experiment. BCA assay kit from Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL) was used to quantify the concentrations of the protein. Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) from various treatments were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight with the primary monoclonal antibody against Bad (at a 1:1000 dilution, Cell signaling technology, USA) and GAPDH (1:1000, Santa cruz, USA), at 4°C and were then incubated with horseradish peroxides-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10000 dilution for rabbit antibody, 1:20000 dilution for mouse antibody) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the membranes thrice with TBST, the protein-antibody complex was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, NJ). GAPDH was served as a loading control.

Tissue microarray (TMA) construction and immunohistochemistry

TMA containing 437 HCC and adjacent nontumorous liver tissues were constructed. All of the specimens were fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The corresponding histological H#x0026;E-stained sections were reviewed by a senior pathologist to mark out representative areas. Using a tissue array instrument (Beecher Instruments, Silver Spring, MD), each tissue core with a diameter of 0.6 mm was punched from the marked areas and re-embedded. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis for Bad was performed using a standard two-step method [20]. TMA sections were baked overnight at 37°C, and then deparaffinized and rehydrated. Slides were boiled in Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA; 1 mmol/L; PH 8.0) in a pressure cooker for antigen retrieval. Subsequently, slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with Bad antibody (1:500 dilution). After rinsed with PBS, the slides were incubated with a secondary antibody and stained with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB). Finally, the slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Slides immunoreacted with PBS were used as the negative controls. Stained cell proportions were scored as follows: 0 (<5% stained cell); 1 (6-24% positively stained cells); 2 (25-49% positively stained cells); 3 (50-74% positively stained cells); 4 (75%-100% positively stained cells). Staining intensity was graded according to the following standard: 0 (no staining); 1 (weak staining = light yellow); 2 (moderate staining = yellow brown) and 3 (strong staining = brown). The product of [positively stained cell proportion x stained intensity] served as the receptor score. The median value of IHC scores was 4; therefore low and high expression was set at scores of <4 and ≥4, respectively [21].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Student’s t test was used for comparison between groups. The X2 test was performed to analyze the correlation between Bad expression and clinic pathological parameters. The Kaplan-Meier method (the log-rank test) was used for survival curves. Cox regression model with stepwise manner (forward, likelihood ratio) was utilized to perform a multivariate analysis. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

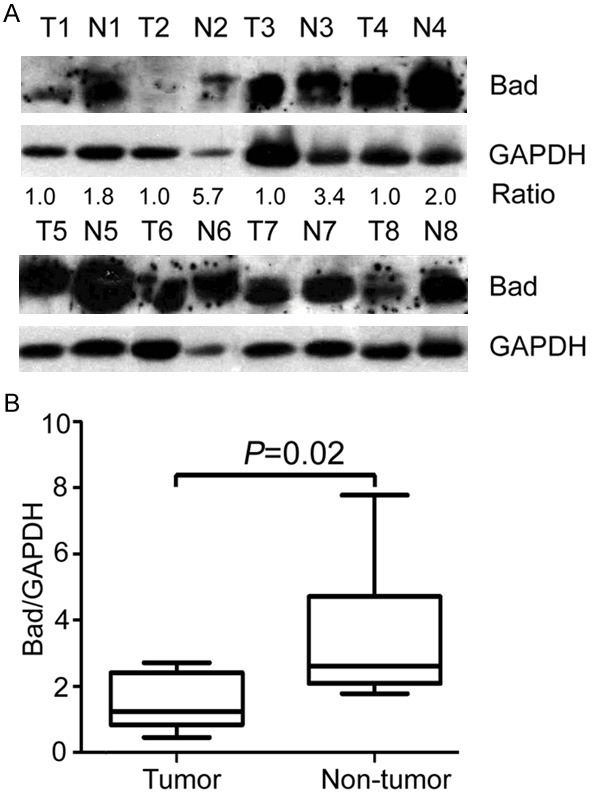

Bad is decreased in fresh HCC tissues

We first examine the expression level of Bad in 8 paired HCC tissues by western blot. According to the results, the expression of Bad was noticeably lower in HCC tissues than that in the corresponding adjacent nontumorous tissues in 62.5% (5/8) of cases (Figure 1A). Comparison of the relevant densities indicated a significant decrease of Bad expression in tumor tissues (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Bad expression is down-regulated in fresh HCC samples. A. Expression of Bad in 8 paired HCC fresh tissue samples (T) and the corresponding nontumorous tissue samples (N) was determined by western blot. GAPDH was used as loading control. B. Relative Bad intensity normalized to GAPDH was calculated by Wilcoxon matched paired test (n = 8).

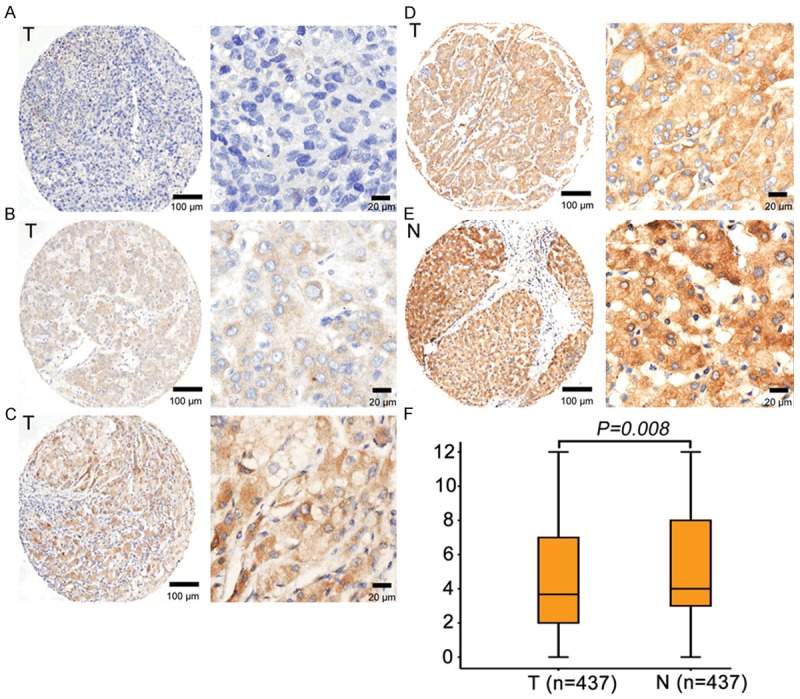

Low Bad expression is associated with the poor clinicopathological parameters

In order to detect the expression of Bad in clinical HCC samples, 437 paraffin-embedded HCC tissues were collected to construct tissue microarray. Results of IHC revealed that Bad was mainly presented in the cytoplasm in both tumorous tissues and nontumorous tissues (Figure 2A-E). In 50.6% (221/437) of HCC tissues, Bad expression was remarkably reduced in tumor. Furthermore, low Bad expression in tumor tissue was identified in 53.5% (234/437) of cases, according to the cutoff value defined by IHC score. Statistically, Bad expression was significantly lower in tumor tissue (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Expression of Bad was decreased in HCC tissues by IHC. Representative micrographs of negative (A), weak (B), moderate (C) and strong (D) staining of Bad in HCC tissues, as well as high expression of Bad in normal liver tissue (E) were shown. (F) Reproducibility of the measurement in all 437 patients was calculated using the Wilcoxon matched paired test.

We next intended to disclose the clinical significance of Bad in HCC. The relationship between Bad expression and clinicopathological features was analyzed. Significant differences were revealed in clinical stage (P=0.007), tumor size (P=0.008), vascular invasion (P=0.024), tumor differentiation (P=0.018) and AFP level (P=0.039) (Table 1). There was no statistical relationship between Bad expression and the rest clinic pathological parameters, including age, gender, cirrhosis, HBsAg and tumor multiplicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation of clinicopathological parameters and Bad expression in the HCC (n=437)

| Variable | All cases | Low expression | High expression | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)b | 0.110 | |||

| <49 | 203 | 117 (57.6%) | 86 (42.3%) | |

| ≥49 | 234 | 117 (50.0%) | 117 (50.0%) | |

| Gender | 0.128 | |||

| Male | 397 | 208 (52.4%) | 189 (47.6%) | |

| Female | 40 | 26 (65.0%) | 14 (35.0%) | |

| HBsAg | 0.438 | |||

| Positive | 368 | 200 (54.3%) | 168 (45.7%) | |

| Negative | 69 | 34 (49.3%) | 35 (50.7%) | |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 0.039 | |||

| <20 | 103 | 46 (44.7%) | 57 (55.3%) | |

| ≥20 | 334 | 188 (56.3%) | 146 (43.7%) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.096 | |||

| Yes | 365 | 189 (51.8%) | 176 (48.2%) | |

| No | 72 | 45 (62.5%) | 27 (37.5%) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.008 | |||

| <5 | 94 | 39 (41.5%) | 55 (58.5%) | |

| ≥5 | 343 | 195 (56.9%) | 148 (43.1%) | |

| Tumor multiplicity | 0.075 | |||

| Single | 269 | 135 (50.2%) | 134 (49.8%) | |

| Multiple | 168 | 99 (58.9%) | 69 (41.1%) | |

| Differentiation | 0.018 | |||

| Well-Moderate | 305 | 152 (49.8%) | 153 (50.2%) | |

| Poor-undifferentiated | 132 | 82 (62.1%) | 50 (37.9%) | |

| Stage | 0.007 | |||

| I-II | 237 | 113 (47.7%) | 124 (52.3%) | |

| III-IV | 200 | 121 (60.5%) | 79 (39.5%) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.024 | |||

| Yes | 94 | 60 (63.8%) | 34 (36.2%) | |

| No | 343 | 174 (50.7%) | 169 (49.3%) |

Chi-square test;

Median age;

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

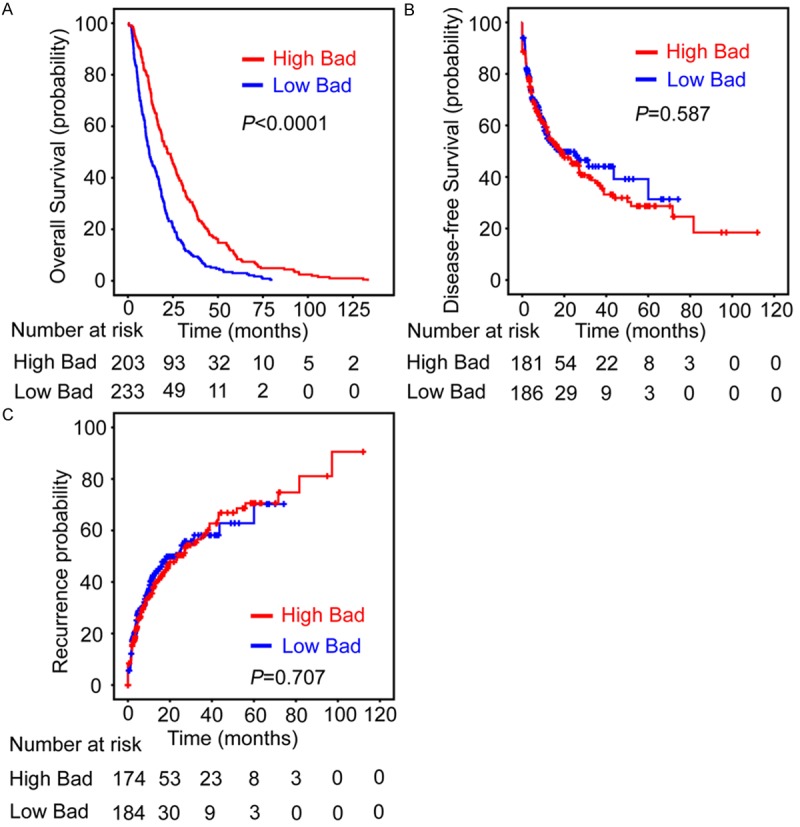

Bad expression is correlated to poor outcomes in HCC

In the cohort of this study, the mean survival time was 29.2 months for the patients with high Bad expression, while it was 16.8 months for patients with low Bad expression. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to determine the correlation between Bad expression and the survival of HCC patients. The results suggested that patients with low Bad expression were likely to be with significantly shorter overall survival (P<0.0001, Figure 3A) but not disease-free survival (P=0.587, Figure 3B) and recurrence probability (P=0.707, Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Low Bad expression in HCC tissue indicates unfavorable overall survival. Probabilities of overall survival (A), disease-free survival (B) and recurrence-free survival (C) of 437 HCC patients were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank test).

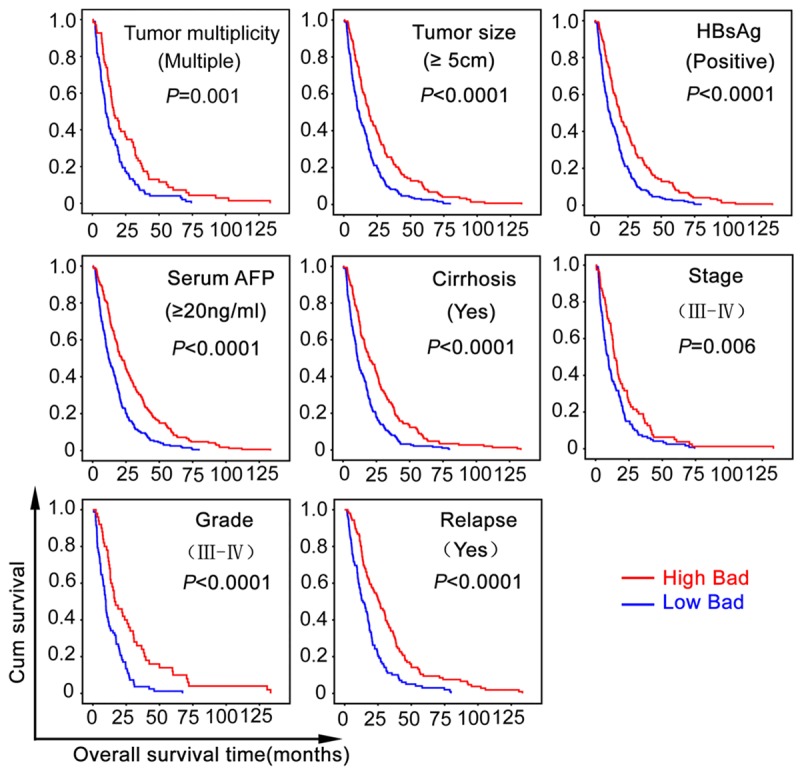

The prognostic value of Bad was further confirmed by stratified survival analysis. Low expression of Bad was closely connected with poor overall survival after surgical resection in eight subgroups classified by the factors contributing to poor outcome of HCC patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The correlation of Bad expression with overall survival was confirmed in morphologic and pathological HCC subgroups. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses (log-rank test) were performed in eight subgroups divided by the factors contributing to poorer outcomes of HCC patients.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic variables in HCC patients

We next evaluated the effect of Bad, as well as the other clinicopathologic parameters, on prognosis of HCC by using univariate analysis. Results indicated that Bad, serum AFP level, tumor size, tumor multiplicity, tumor differentiation, clinical stage, liver cirrhosis and vascular invasion were responsible for efficacy of surgical treatment in HCC patient (P<0.0001) (Table 2). Furthermore, multiple Cox regression analysis indicated that Bad expression was an independent predictor for overall survival of HCC patients (HR=0.589, 95% confident interval: 0.483-0.717, P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of clinicopathological and Bad for overall and disease-free survival in HCC (n=437)

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Overall survival | ||||

| Age (<49 vs. ≥49 years) | 0.905 (0.749-1.093) | 0.301 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.980 (0.707-1.358) | 0.903 | ||

| HBV (positive vs. negative) | 1.090 (0.840-1.413) | 0.517 | ||

| Tumor size (<5 vs. ≥5 cm) | 1.525 (1.212-1.919) | 0.000 | 1.159 (0.894-1.503) | 0.264 |

| Tumor multiplicity (single vs. multiple) | 1.261 (1.038-1.531) | 0.019 | 0.953 (0.761-1.194) | 0.677 |

| Liver cirrhosis (yes vs. no) | 0.737 (0.571-0.950) | 0.019 | 0.846 (0.651-1.100) | 0.213 |

| AFP (<20 vs. ≥20 ng/mL) | 1.479 (1.183-1.849) | 0.001 | 1.303 (1.037-1.638) | 0.023 |

| Vascular invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.930 (1.531-2.434) | 0.000 | 1.432 (1.107-1.854) | 0.006 |

| Tumor differentiation | 1.328 (1.080-1.633) | 0.007 | 1.188 (0.962-1.467) | 0.109 |

| TNM (I-II vs. III-IV) | 1.768 (1.460-2.141) | 0.000 | 1.363 (1.053-1.764) | 0.019 |

| Bad expression (low vs. high) | 0.535 (0.441-0.650) | 0.000 | 0.589 (0.483-0.717) | 0.000 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| Age (<49 vs. ≥49 years) | 0.917 (0.702-1.197) | 0.523 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.014 (0.640-1.607) | 0.954 | ||

| HBV (positive vs. negative) | 1.059 (0.727-1.542) | 0.765 | ||

| Tumor size (<5 vs. ≥5 cm) | 1.021 (0.751-1.387) | 0.897 | ||

| Tumor multiplicity (single vs. multiple) | 0.820 (0.616-1.091) | 0.173 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis (yes vs. no) | 0.819 (0.578-1.159) | 0.259 | ||

| AFP (<20 vs. ≥20 ng/mL) | 1.145 (0.843-1.555) | 0.385 | ||

| Vascular invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.118 (0.792-1.578) | 0.525 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.966 (0.714-1.307) | 0.823 | ||

| TNM (I-II vs. III-IV) | 0.844 (0.639-1.114) | 0.230 | ||

| Bad expression (low vs. high) | 1.077 (0.822-1.410) | 0.590 | ||

Discussion

Bad is a BH3-only protein which is selectively dimerized with Bcl-xL or Bcl-2, neutralizing their death repression effect and facilitating cell apoptosis [22-24]. It is differently expressed in human cancers. In the present study, Bad was markedly down-regulated in HCC tissues, compared with the corresponding adjacent nontumorous tissues, using TMA-Based IHC in a large cohort of 437 patients. In line with our data, Antoine et al. showed that protein expression of Bad was gradually increased from HCC to normal liver in three paired fresh tissues [19]. The downregulation of the proapoptotic counterpart Bad may be a pivotal event responsible for the reducing sensitivity to apoptosis in HCC progression.

Our data showed that low Bad expression was associated with large tumor size, higher serum AFP level, poor tumor differentiation, advanced clinical stage and high incidence of vascular invasion, indicating that the loss of Bad might serve as a hallmark of advanced tumor stage. The relationship of Bad expression level with clinicopathological parameters has also been determined in other tumors. Decreased Bad was closely correlated with larger tumor size and estrogen receptor (ER) in primary breast cancer [16]. Low Bad expression was shown to be significantly associated with advanced clinical stages in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [18]. In response to survival factors, Bad is phosphorylated, leading to the binding to 14-3-3 and the injury of its death-promoting activity [25,26]. Whether Bad is phosphorylated in tumor tissues required further investigation.

Prognostic analysis indicated that HCC patients with high Bad expression survived longer in our studied cohort. Furthermore, Cox regression analysis revealed that Bad remained to be an independent prognostic factor for overall survival. This might be due to the pro-survival effect of Bad depletion. Yu et al. reported that loss of Bad reduced the chemosensitivity of Epirubicin Adriamycin (EADM) and Navelbine (NVB) in human breast carcinoma [27]. In addition, recent studies provided a comprehensive understanding of the role of Bad in tumorigenesis. Bad-deficient mice possess an increased incidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by exposed to sublethal gamma-irradiation [28]. The silence of the Akt/Bad pathway paves the way for malignant transformation into Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) [29]. Therefore, low expression of Bad in HCC tissues may promote tumor generation and progression, in turn to result in adverse prognosis.

Stratified survival analysis further indicated that low Bad expression was significantly correlated with shorter overall survival after surgical resection in eight subgroups classified by the factors conferring to adverse clinical outcome. This suggested that low expression of Bad could be of clinical use for defining a set of patients with adverse prognosis. It is generally accepted that histology differentiated degree, vascular invasion and serum AFP level could affect the prognosis of HCC patients [30-32]. However, there are variable limits in providing critical information for patient prognosis prediction. Therefore, monitoring the dynamic expression of Bad may replenish the panel to identify a set of patients at risk of HCC progression.

In conclusion, our data showed that decreased Bad expression is related to larger tumor size, higher serum AFP level, advanced clinical sta-ge, poorer tumor differentiation and high incidence of vascular invasion. Low Bad expression was correlated with unfavorable survival. Our study therefore provides an promising biomarker for predicting the postsurgical prognosis of patients who suffered from HCC.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81201717, 81372572), and the Project of State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao L, Li H, Shi Y, Wang G, Liu L, Su C, Su R. Nanoparticles inhibit cancer cell invasion and enhance antitumor efficiency by targeted drug delivery via cell surface-related GRP78. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:245–256. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S74868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveri RS, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;380:470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61285-9. author reply 470-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song IS, Jun SY, Na HJ, Kim HT, Jung SY, Ha GH, Park YH, Long LZ, Yu DY, Kim JM, Kim JH, Ko JH, Kim CH, Kim NS. Inhibition of MKK7-JNK by the TOR signaling pathway regulator-like protein contributes to resistance of HCC cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1341–1351. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao H, Liu C. miR-429 represses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in HBV-related HCC. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EI-Emshaty HM, Saad EA, Toson EA, Abdel Malak CA, Gadelhak NA. Apoptosis and cell proliferation: correlation with BCL-2 and P53 oncoprotein expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1393–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagasawa T, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Toyoda H, Matsuura J, Kumada T, Kozawa O. Heat shock protein 20 (HSPB6) regulates apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells: Direct association with Bax. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:1291–1295. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, Alberts SR, Windschitl HE, Sargent DJ. Proapoptotic Bad and Bid protein expression predict survival in stages II and III colon cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4128–4133. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seow HF, Yip WK, Loh HW, Ithnin H, Por P, Rohaizak M. Immunohistochemical detection of phospho-Akt, phospho-BAD, HER2 and oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in Malaysian breast cancer patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2010;16:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yancey D, Nelson KC, Baiz D, Hassan S, Flores A, Pullikuth A, Karpova Y, Axanova L, Moore V, Sui G, Kulik G. BAD dephosphorylation and decreased expression of MCL-1 induce rapid apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta SR, Katsov A, Hu L, Petros A, Fesik SW, Yaffe MB, Greenberg ME. 14-3-3 proteinsand survival kinases cooperate to inactivate BAD by BH3 domain phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2000;6:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta SR, Ranger AM, Lin MZ, Sturgill JF, Ma YC, Cowan CW, Dikkes P, Korsmeyer SJ, Greenberg ME. Survival factor-mediated BAD phosphorylation raises the mitochondrial threshold for apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2002;3:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy SS, Madesh M, Davies E, Antonsson B, Danial N, Hajnoczky G. Bad targets the permeability transition pore independent of Bax or Bak to switch between Ca2+-dependent cell survival and death. Mol Cell. 2009;33:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cekanova M, Fernando RI, Siriwardhana N, Sukhthankar M, Parra C, Woraratphoka J, Malone C, Strom A, Baek SJ, Wade PA, Saxton AM, Donnell RM, Pestell RG, Dharmawardhane S, Wimalasena J. BCL-2 family protein, BAD is down-regulated in breast cancer and inhibits cell invasion. Exp Cell Res. 2015;331:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Bazz YO, Underwood JC, Brown BL, Dobson PR. Prognostic significance of Akt, phospho-Akt and BAD expression in primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Y, Liu D, Chen B, Zeng J, Wang L, Zhang S, Mo X, Li W. Loss of Bad expression confers poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1648–1655. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Troutaud D, Petit B, Bellanger C, Marin B, Gourin-Chaury MP, Petit D, Olivrie A, Feuillard J, Jauberteau MO, Bordessoule D. Prognostic significance of BAD and AIF apoptotic pathways in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10:118–124. doi: 10.3816/CLML.2010.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galmiche A, Ezzoukhry Z, Francois C, Louandre C, Sabbagh C, Nguyen-Khac E, Descamps V, Trouillet N, Godin C, Regimbeau JM, Joly JP, Barbare JC, Duverlie G, Maziere JC, Chatelain D. BAD, a proapoptotic member of the BCL2 family, is a potential therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1116–1125. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada H, Sano Y. The biotinylation of the rabbit serotonin antibody and its application to immunohistochemical studies using the two-step ABC method. Histochemistry. 1985;83:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00684372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Epithelioid sarcoma: new insights based on an extended immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1161–1168. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1161-ESNIBO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q, Leber B, Andrews DW. Interactions of pro-apoptotic BH3 proteins with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins measured in live MCF-7 cells using FLIM FRET. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3536–3542. doi: 10.4161/cc.21462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aranovich A, Liu Q, Collins T, Geng F, Dixit S, Leber B, Andrews DW. Differences in the mechanisms of proapoptotic BH3 proteins binding to Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 quantified in live MCF-7 cells. Mol Cell. 2012;45:754–763. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long J, Liu L, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Shangary S, Yi H, Wang S. Optimization and validation of mitochondria-based functional assay as a useful tool to identify BH3-like molecules selectively targeting anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada H, Becknell B, Wilm M, Mann M, Huang LJ, Taylor SS, Scott JD, Korsmeyer SJ. Phosphorylation and inactivation of BAD by mitochondria-anchored protein kinase A. Mol Cell. 1999;3:413–422. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu C, Minemoto Y, Zhang J, Liu J, Tang F, Bui TN, Xiang J, Lin A. JNK suppresses apoptosis via phosphorylation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein BAD. Mol Cell. 2004;13:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu B, Sun X, Shen HY, Gao F, Fan YM, Sun ZJ. Expression of the apoptosis-related genes BCL-2 and BAD in human breast carcinoma and their associated relationship with chemosensitivity. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:107. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranger AM, Zha J, Harada H, Datta SR, Danial NN, Gilmore AP, Kutok JL, Le Beau MM, Gre-enberg ME, Korsmeyer SJ. Bad-deficient mice develop diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9324–9329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533446100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akl H, Badran BM, Zein NE, Bex F, Sotiriou C, Willard-Gallo KE, Burny A, Martiat P. HTLV-I infection of WE17/10 CD4+ cell line leads to progressive alteration of Ca2+ influx that eventually results in loss of CD7 expression and activation of an antiapoptotic pathway involving AKT and BAD which paves the way for malignant transformation. Leukemia. 2007;21:788–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou L, Rui JA, Wang SB, Chen SG, Qu Q. Prognostic factors of solitary large hepatocellular carcinoma: the importance of differentiation grade. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marwoto W, Miskad UA, Siregar NC, Gani RA, Boedihusodo U, Nurdjanah S, Suwarso , Watadianto , Boedi P, Hasan HA, Akbar N, Noer HM, Hayashi Y. Immunohistochemical study of P53, PCNA and AFP in hepatocellular carcinoma, a comparison between Indonesian and Japanese cases. Kobe J Med Sci. 2000;46:217–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Steinmuller T, Herrmann M, Radke C, Berg T, Settmacher U, Neuhaus P. Vascular invasion and histopathologic grading determine outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2001;33:1080–1086. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]