Abstract

Two semipermeable, hollow fiber phantoms for the validation of perfusion-sensitive magnetic resonance methods and signal models are described. Semipermeable hollow fibers harvested from a standard commercial hemodialysis cartridge serve to mimic tissue capillary function. Flow of aqueous media through the fiber lumen is achieved with a laboratory-grade peristaltic pump. Diffusion of water and solute species (e.g., Gd-based contrast agent) occurs across the fiber wall, allowing exchange between the lumen and the extralumenal space. Phantom design attributes include: i) small physical size, ii) easy and low-cost construction, iii) definable compartment volumes, and iv) experimental control over media content and flow rate.

Keywords: MR phantom design, hollow fiber bioreactor, dialyzer, perfusion, semipermeable hollow fiber

INTRODUCTION

Perfusion-sensitive magnetic resonance (MR) techniques, such as dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) and arterial spin-labeled (ASL) MR, are powerful methods for defining and monitoring tissue vascular status, and changes therein, in the face of physiologic challenge, normal and pathologic. DCE and ASL MR methods use exogenous and endogenous MR-sensitive diffusible tracers, respectively. Analysis of the DCE or ASL MR signal characterizes tissue vasculature by estimating parameters associated with multi-compartment kinetic models, which seek to describe the relevant biophysical properties of a given tissue’s vascular system. Quantitative validation of a particular DCE or ASL MR method and its related signal model is difficult, often impossible, in vivo. Phantoms, designed to mimic salient properties of tissue vasculature, provide a platform for validation of perfusion- sensitive MR methods and signal models. Importantly, phantoms allow MR-derived kinetic parameters to be compared with alternative, “gold standard” measurements of these same parameters.

The ideal MR perfusion phantom should contain simulated vasculature enabling i) lumenal flow, i.e., media flow through the interior of the mock capillaries, and ii) diffusion of water and solutes (e.g., Gd-based contrast agent) across the vessel wall, i.e., exchange of water and solutes between lumenal and extralumenal spaces. The phantom should allow independent determination of parameters characterizing the relevant kinetic model, such as the DCE model’s volume wash-in transfer constant (Ktrans) and wash-out rate constant (kep), and the ASL model’s perfusion rate (f) and mean transit time.

MR methods and signal-model validation would be enabled by a simple multicompartment phantom constructed of spaces with known dimensions, as fractional volumes are often important model parameters. Likewise, MR-independent knowledge of experimental parameters would allow quantitative comparison to MR-derived signal/kinetic model-parameter values. These include, for example, media flow rate and velocity, contrast-agent “arterial” input function, and diffusivity of water and contrast agent across the fiber wall. Finally, a phantom requiring only inexpensive, simple components and construction methods while maintaining an overall diameter of a few centimeters or less, would facilitate testing/validation of a broad range of perfusion-sensitive MR techniques on preclinical (small-animal) MRI scanners.

Hollow fiber modules (HFM), in the form of commercial hemodialyzers (e.g., Fresenius Medical Care AG, Bad Homberg, Germany; Baxter International, Deerfield, IL), hollow fiber bioreactors, and small-volume filtration and concentration systems (e.g., Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA; FiberCell Systems, Frederick, MD) could potentially serve as such phantoms. HFM contain semipermeable hollow fibers that mimic vasculature. The straw-like polymer fibers permit restricted diffusion of small molecules across the fiber wall while blocking passage of larger particles such as cells, hence the term “semipermeable.” The design of HFM permits media flow; thus, simulated perfusion experiments are possible.

MR imaging and spectroscopy studies of HFM have been published, including one in which a commercial dialyzer was used as a phantom for validation of perfusion measurements (1). However, most imaging studies have focused on testing and improving the efficacy of dialyzers by directly measuring flow (velocity) within the dialysis fibers to probe homogeneous fluid transport (2–9) and assess the impact of different design innovations (10, 11). MR imaging and spectroscopy studies of HFM bioreactors have also been reported. As the native application of bioreactors is support of cell cultures, the majority of this literature is focused on monitoring and characterizing cell growth within the bioreactor via diffusion weighting, velocity encoding, or contrast enhancement (12–14). HFM perfusion measurements using spectroscopic methods have also been reported (9, 15–17).

Despite the many advantages of commercial HFM, there are limitations to their use as perfusion-sensitive MR phantoms. HFM fiber-packing density is fixed by the manufacturer for optimal hemodialysis/microfiltration-concentration/cell growth, limiting the options available for perfusion-sensitive MR phantoms. The chemical composition of the semipermeable hollow fibers, and thus the porosity/molecular weight cutoff, is likewise fixed by the manufacturer. We further note that human dialyzer HFM, manufactured for clinical efficiency, have a relatively large size that constrains both MR protocols [e.g., field-of-view (FOV) vs. spatial resolution] and access to smaller magnet-bore scanners.

Herein, we present the design and construction of two perfusion-sensitive MR phantoms. These laboratory constructed phantoms can be designed with specific fiber dimensions and numbers, allowing accurate calculation of fractional compartment volumes. Further, fibers of various compositions can be obtained from commercial suppliers, allowing selection of permeability characteristics appropriate for the research question of interest. Finally, other parameters salient to perfusion-sensitive MR techniques, including media flow rate, velocity, and input function, can be controlled experimentally. The phantoms are of small dimensions, thereby facilitating high spatial-resolution imaging on preclinical MR imaging scanners by permitting the use of small, high-sensitivity volume coils. Ebrahimi et al. recently presented a phantom with microfluidic channels (18). The “vessels” (channels) of the phantom are similar in size to those found in vivo. The phantoms presented in this manuscript contain vessels of larger dimensions that, unlike microfluidic channels, allow diffusion of water and other molecules through the fiber wall.

Demonstrating two extremes, one phantom consists of a single fiber suspended through the center of a capillary tube; the other phantom consists of multiple fibers densely packed in heat-shrink tubing. Both phantoms permit lumenal and, if desired, extralumenal flow/access. Uniformity of commercial fibers allows controlled gold standard experiments on a single or a small number of fibers, e.g., measurement of the diffusivity or permeability of water or contrast agent across the fiber wall.

PHANTOM DESIGN

Single-Fiber Phantom Overview

The overall design of the single-fiber phantom is shown in Fig. 1. The phantom consists of a single, semi-permeable hollow fiber (inner diameter (ID) = 0.20 mm; 10.1002/cmr.b wall thickness, slice thickness (TH) of the wall = 0.04 mm) suspended in a capillary tube (ID = 1.00 mm). The fiber was harvested from a commercial HFM used for clinical hemodialysis, vide infra. Three physical compartments exist within the phantom: the fiber lumen, the fiber wall, and the extrafiber space. For many experiments (e.g., T1 in the absence of lumenal flow or of a molecule that is freely diffusible in both the fiber wall and the extralumenal space), the fiber wall and the extrafiber space constitute a single compartment, collectively referred to as the extralumenal space.

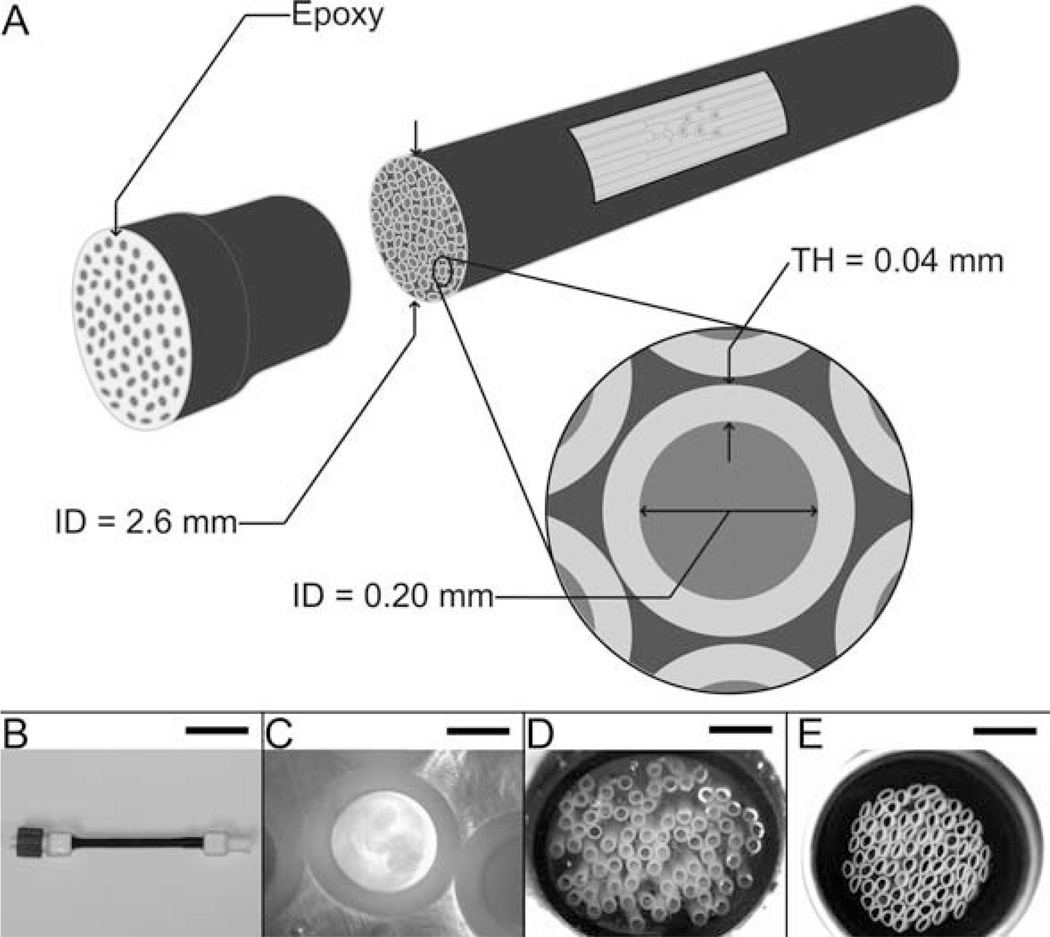

Figure 1.

Single-fiber phantom. Left inset: schematic of the interior of the Luer-lock end piece. Center inset: schematic interior of the center portion of the phantom; sagittal view. Right inset: schematic interior of the center portion of the phantom; transaxial view.

In the single-fiber phantom, the lumenal and extrafiber compartments are independently accessible. For the fiber lumen, access is provided by Luer fittings, mounted directly on the two ends of the capillary tube (Fig. 1), through which a single hollow fiber passes. For the extrafiber space, access is via a catheter, consisting of a 10″ piece of tubing (ID = 0.20 mm; TH = 0.10 mm) with an attached Luer fitting. The lumenal and extrafiber compartments communicate only through the wall of the fiber. The connectors allow for efficient purging of these compartments, as well as flow in either compartment during experimentation. In our experiments, the flow was achieved with a standard laboratory peristaltic pump, vide infra.

A design feature of the single-fiber phantom is the ability to control the relative sizes of the lumenal and extrafiber compartments by changing capillary tubes. The phantom shown in Fig. 1 uses a capillary tube with ID = 1.00 mm; we have also constructed phantoms using capillary tubes with ID = 0.50 mm. These two arrangements result in lumen:fiber wall:extrafiber space fractional volumes of 0.04:0.04:0.92 and 0.16:0.15:0.69, respectively. The length of the phantom can also be adjusted as required. Typically, capillary tubes for our phantoms are approximately 3 cm long.

Multifiber Phantom Overview

The overall design of the multifiber phantom is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The phantom consists of multiple semipermeable fibers bundled inside heat-shrink tubing (ID = 2.6 mm after shrinkage). As with the single-fiber phantom, three physical compartments exist within the multifiber phantom: the fiber lumen, the fiber wall, and the extrafiber space. Again, under many experimental conditions, the fiber wall and the extrafiber space can be considered as a single compartment, the extralumenal space.

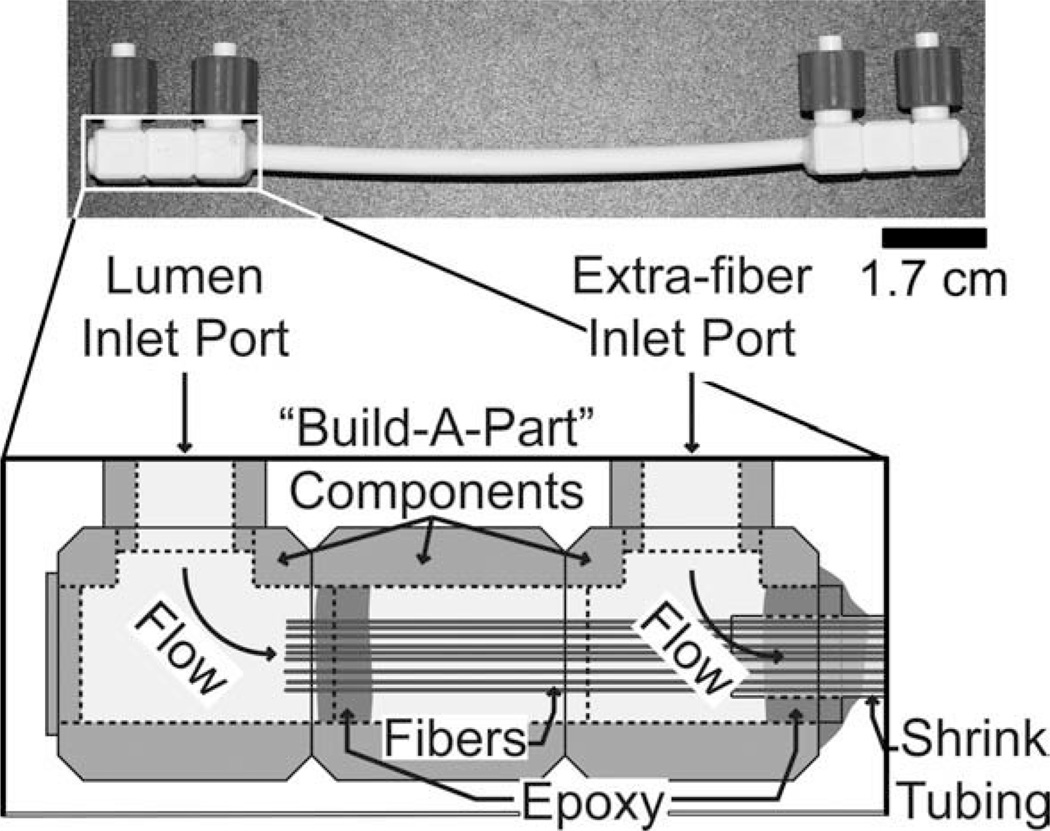

Figure 2.

Multifiber phantom; lumenal compartment access only. A: Schematic of the design and dimensions of the multifiber phantom. B: Photograph of the multifiber phantom (scale bar = 2.50 cm). C: Microscope image of a transaxial cross-section of a single fiber (40× magnification, scale bar = 100 µm). D: Microscope image of a transaxial cross-section of the end of the phantom, i.e., fibers fixed in epoxy (4× magnification, scale bar = 1 mm). E: Microscope image of a transaxial cross-section of the center portion of the phantom; fibers tightly bundled (4×, scale bar = 1 mm). Note: the slight deformity seen in some fibers in E occurred while cutting the phantom for the microscope image.

Figure 3.

Multifiber phantom with lumenal and extrafiber compartment access. Inset: schematic of the interior of the “Build-A-Part” Luer-lock connector.

External access to compartments is shown in two different configurations in Figs. 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows the geometry more commonly used in our lab. In this configuration, external access is available only to the lumenal compartment, via Luer fittings mounted directly on the two ends of the heat shrink tubing. Figure 3 presents a second geometry, in which both the fiber lumen and the extrafiber space are accessible externally.

The relative ratios of the different compartments can be altered by changing i) the number of fibers in the bundle and/or ii) the diameter of the heat-shrink tubing, as illustrated in two example setups [Figs. 4(C,D) and 5(C,D)]. In one case (C), 75 fibers placed into heat-shrink tubing that is then contracted produce a densely-packed fiber-bundle phantom having an ID of 2.6 mm and lumen:fiber wall:extrafiber space fractional volumes of 0.44:0.43:0.13. In a second case (D), 50 fibers placed into 4.0-mm ID heat-shrink tubing that is not further contracted produce a loosely packed fiber-bundle phantom with lumen:fiber wall:extrafiber fractional volumes 0.13:0.12:0.75. Multifiber phantoms have been constructed with heat-shrink tubing lengths from 5 cm to 10 cm.

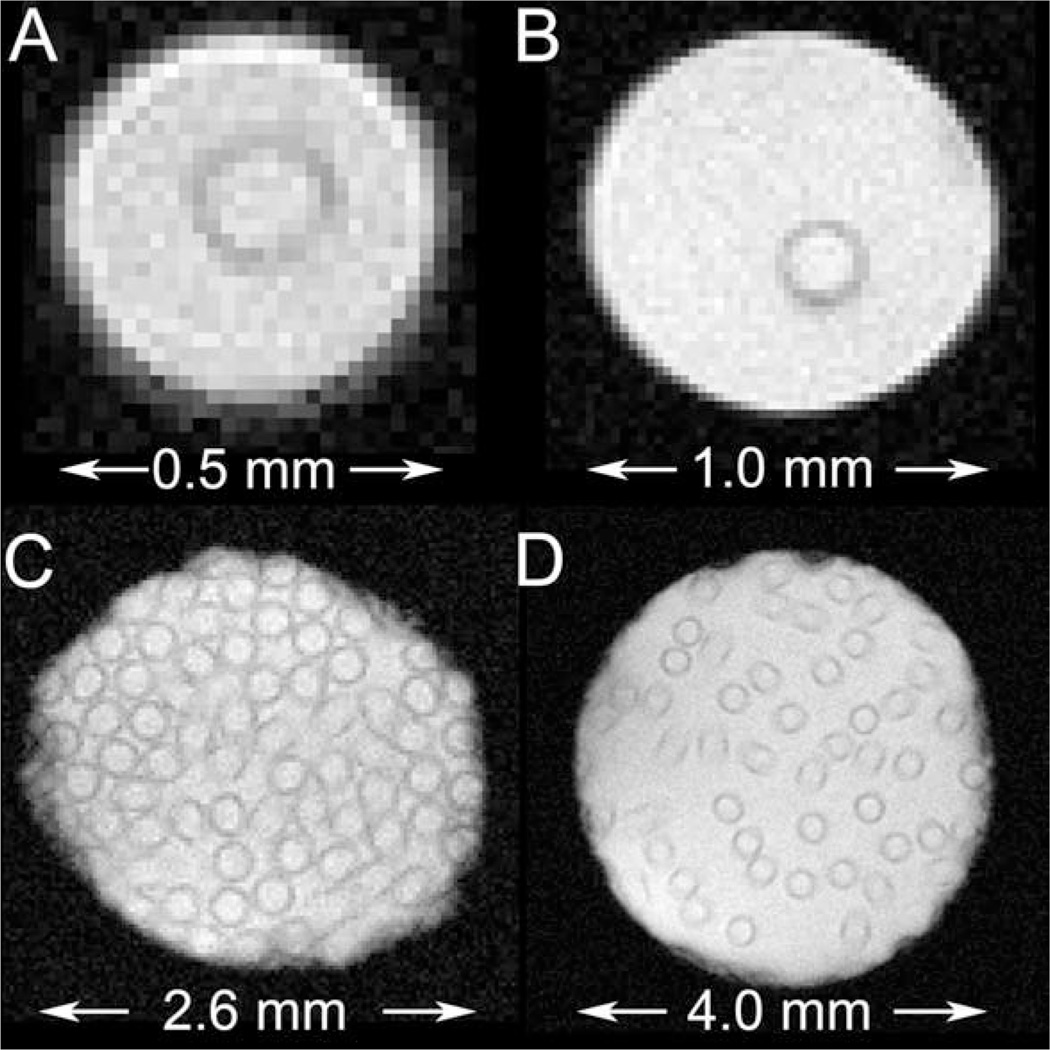

Figure 4.

Gradient-echo images of various semipermeable hollow fiber phantoms, without lumenal flow. A: single- fiber phantom; ID = 0.5 mm. B: single-fiber phantom; ID = 1.0 mm. C: multifiber phantom; 75 fibers; ID = 2.6 mm. D: multifiber phantom; 50 fibers; ID = 4.0 mm.

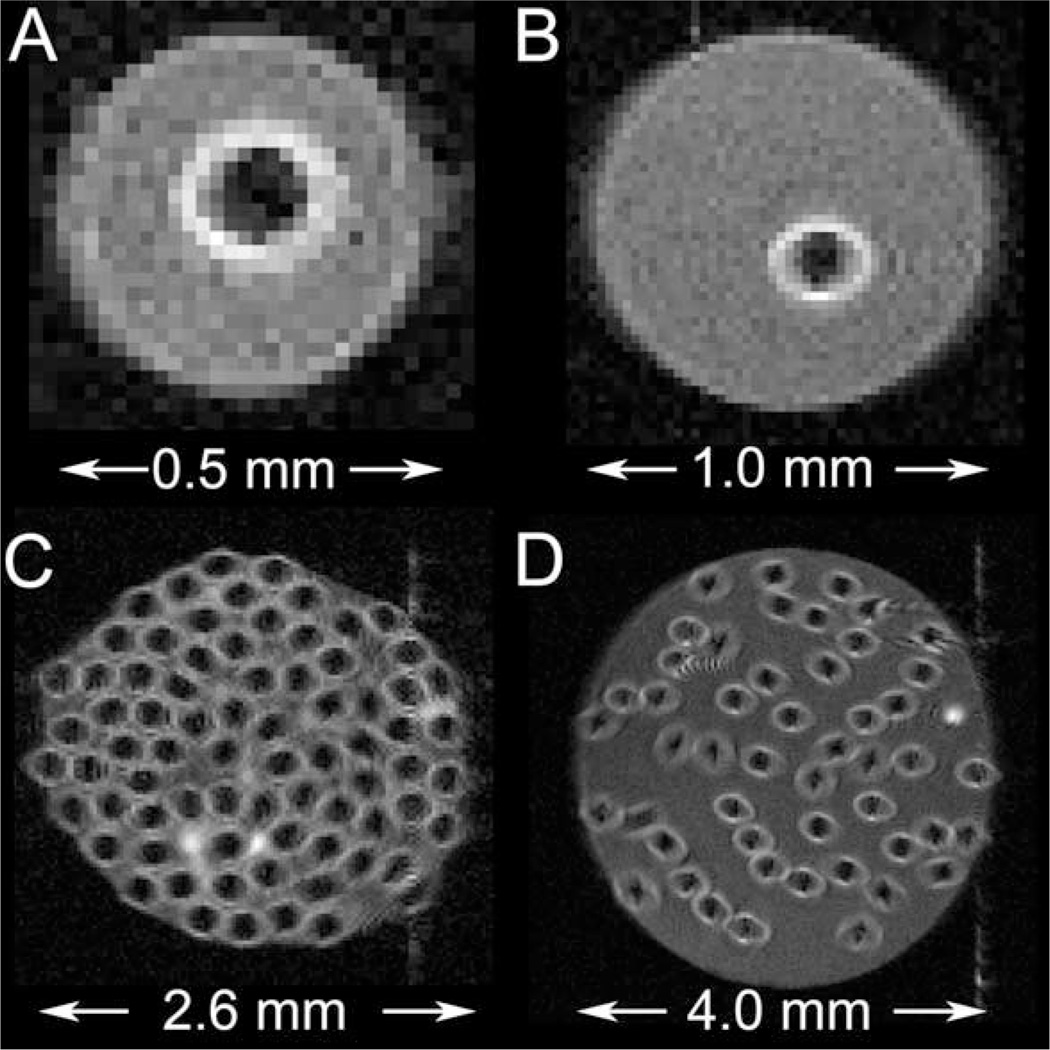

Figure 5.

Spin-echo images of various semipermeable hollow fiber phantoms with lumenal flow. A: Single-fiber phantom; ID = 0.5 mm. B: Single-fiber phantom; ID = 1.0 mm. C: Multifiber phantom; 75 fibers; ID = 2.6 mm. D: Multifiber phantom; 50 fibers; ID = 4.0 mm.

CONSTRUCTION OF PHANTOMS

General Considerations

Devcon 5 Minute Epoxy was used for the construction of all phantoms (ITW Devcon; Danvers, MA). To facilitate precision application of epoxy, a 10-mL syringe with a 19G blunt-tipped needle was used to first draw and then apply the freshly mixed epoxy. Care was taken not to plug the ends of catheters and fibers used in phantoms with epoxy. All fibers used were harvested from a Fresenius Optiflux F-160NR dialyzer. Fibers were cut with a razor blade.

Single-Fiber Phantom

In preparation for phantom construction, two Luerlock end pieces were fashioned from 1-mL Luer-Lok syringes (P/N 309628; Beckton, Dickinson and Company; Franklin Lakes, NJ). The syringes were cut to size (~1.5 cm) and 1.0-mm diameter holes were drilled at ~45° angle, as shown in the left inset of Fig. 1. Mouse tail-vein catheters (MTV-01; Strategic Applications; Libertyville, IL) were threaded through the holes.

A semipermeable hollow fiber (length: ~15 cm) was threaded through a capillary tube cut to the desired length. The tips of the two catheters, providing access to the extralumenal space, vide supra, were inserted ~0.5 cm into opposite ends of the capillary tube. After axially centering the fiber in the capillary, the fiber and catheter tips were fixed in place with epoxy while applying gentle tension to the fiber. Once the epoxy cured, the ends of the semipermeable hollow fiber were carefully trimmed, leaving ~0.2 cm extending from the capillary on each side. Next, the two Luer-lock end pieces were centered axially on the ends of the capillary and fixed in place with epoxy. Finally, the holes in the end pieces, through which the catheters were fed, were filled with epoxy.

Multifiber Phantom

Value Plastics “Build-A-Part” components (Value Plastics, Fort Collins, CO) were used to construct the Luer-lock connectors for the multifiber phantoms. These preformed building-block components can be connected to each other, using a small amount of acetone, to form various parts. The Build-A-Part components used in these phantoms consisted primarily of cubes with various pass-through holes, as seen in both Figs. 2 and 3. The end connectors for the multifiber phantom shown in Fig. 2 were constructed from Build-A-Part components before assembly of the phantom, but those used in the multifiber phantom shown in Fig. 3 were assembled as part of the phantom- building process, as noted below.

The phantom shown in Fig. 2 was constructed by first bundling together 75 fibers with a small amount of fishing line and then threading the fiber bundle through generic 1/8″ polyolefin heat-shrink tubing. Epoxy was carefully, but liberally applied on and around the fibers at one end of the phantom. The epoxy was allowed to seep ~0.5 cm (axially) into the heat-shrink tubing and to completely cover the fibers extending outside of the tubing, also a length of ~0.5 cm. After the epoxy cured for 40 min, the fibers at the epoxied end were carefully trimmed with a razor blade, leaving ~0.2 cm exposed beyond the edge of the heat-shrink tubing. Trimming fibers that have been completely encased in epoxy results in a very clean cut and ensures little-to-no fiber occlusions [Fig. 2(D)]. Next, the heat-shrink tubing was gently contracted with a heat gun. The exposed portions of the fibers were covered with aluminum foil to prevent potential heat damage. Epoxy was then applied to the opposite end of the phantom, allowed to cure, and the fibers trimmed. Lastly, the Luer-lock connectors were fixed to the ends of the phantom with epoxy, taking care not to bend or otherwise constrict any of the fiber tips.

Construction of the multifiber phantom shown in Fig. 3 was somewhat more challenging. To ensure that the phantom had a uniform, cylindrical shape, a length of 1/4″ heat-shrink tubing was “preconditioned” by contracting it around a 4-mm outer-diameter glass rod, which was then removed from the tubing. (A light coating of glycerin applied to the 4-mm glass rod before contracting the tubing made it easier to withdraw the rod.) Fifty fibers were bundled and fed through the preconditioned (now 4-mm ID) heat-shrink tubing. The bundle of fibers was then threaded through the first Build-A-Part component (Fig. 3, right side) until ~0.2 cm of the heat-shrink tubing was nested inside the Build-A-Part component. The heat-shrink tubing was fixed to the Build-A-Part component with epoxy, taking care to avoid applying any epoxy to the fibers. The fibers were carefully fed through the second component (Fig. 3, center), which was then connected to the first. The fibers were fixed to each other, and then to the inside of the second component with epoxy, and were trimmed to leave ~0.2 cm exposed. Finally, the third Build-A-Part component was connected (Fig. 3, left side).

Persistent air bubbles, remaining in the interior of the phantoms after being filled with media, were flushed out using the following two-step procedure. First, the phantom was gradually submerged in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask with a sidearm and placed under house vacuum. While under vacuum, the phantom was agitated gently by tapping the flask. Second, the phantom was placed inline and purged with media for 10–60 min, as required.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peristaltic Pumping

Peristaltic pumps (single-fiber phantom: Carter Manostat Cassette Pump; Thermo Scientific-Barnant, Barrington, IL; multifiber phantom: Masterflex L/S Digital Economy Drive; Cole-Parmer Instrument Company; Vernon Hills, IL) were placed just outside the 5-G line of the magnet’s fringe field. To minimize peristalsis, pump heads with eight and six rollers were used for the single- and multifiber phantoms, respectively. Also, small-diameter pump tubing was used to facilitate increased pump-head speeds. Pump tubing with an ID of 0.25 mm was used with the single-fiber phantom (Masterflex Santoprene Tubing; Cole-Parmer; Vernon Hills, IL), whereas tubing with an ID of 1.6 mm was used with the multifiber phantom (Masterflex Tygon Tubing; Cole-Parmer).

MR Imaging

Images were collected on scanners using Oxford Instruments 4.7-T horizontal-bore magnets of either 33- or 40-cm clear bore (Oxford Instruments; Oxford, UK). Both scanners are interfaced with Agilent/Varian DirectDrive™ consoles, and Agilent/Magnex gradient coil assemblies (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA). The gradient-coil assemblies have the following respective characteristics: bore IDs = 12 and 21 cm; max gradient amplitudes = 58 and 28 G/cm; and rise times = 295 and 650 µs. Slice-selective gradient-echo images were acquired without lumenal flow, while spin-echo images were acquired with lumenal flow; flow rate = 0.65 mL/min for single-fiber phantoms and 50 mL/min for multifiber phantoms. The experimental imaging parameters were: repetition time (TR) = 500 ms, echo time (TE) = 10/13.5 ms (gradient-echo/spin-echo), TH of slice = 1.00 mm, and number of transients (NT) = 32. Although the in-plane FOV varied from 6.4 × 0.8 mm2 [Figs. 4(A) and 5(A)] to 6.4 × 6.4 mm2 (Figs. 4(D) and 5(D)], in-plane voxel dimensions were fixed for all images at 25 × 25 µm2.

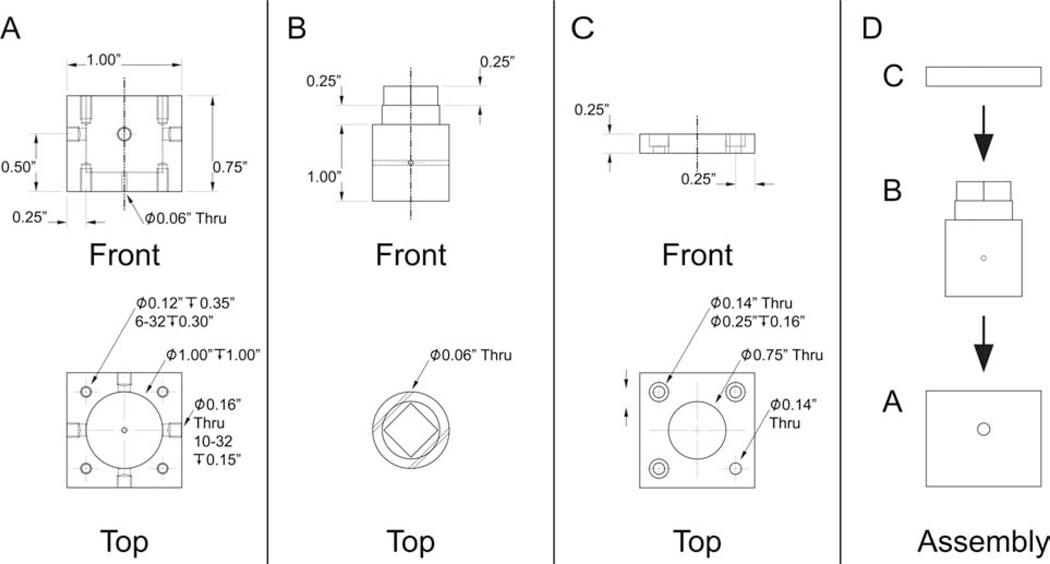

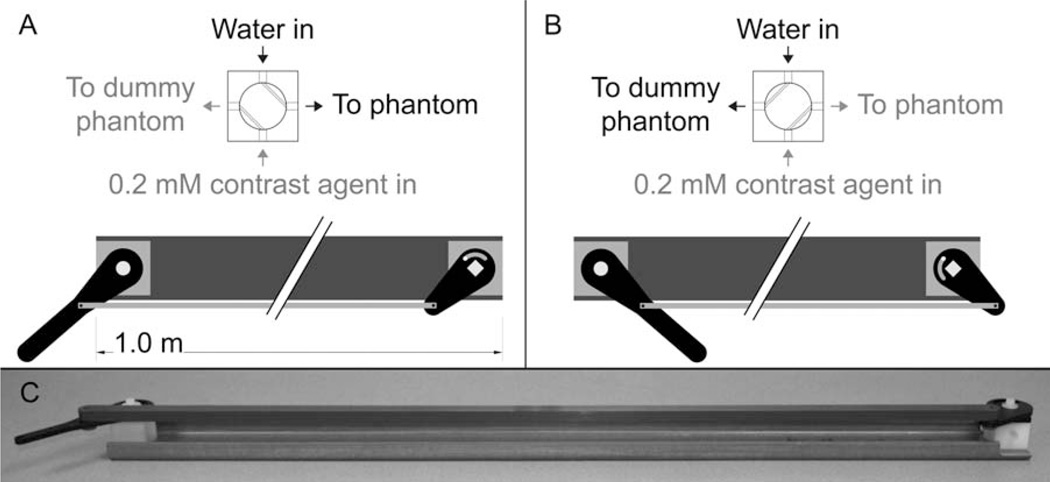

Contrast-Agent Enhancement

To mimic a DCE-MRI experiment, a low-molecular weight Gd-based contrast agent was injected into the lumenal compartment of the multifiber phantom (ID = 2.6 mm; 75 fibers). This injection was achieved by means of a four-way valve located near the phantom that rapidly switched the flowing lumenal solution between pure water and an aqueous solution containing 0.2-mM Gd-BOPTA (gadobenate dimeglumine; MultiHance; Bracco Diagnostics ; Princeton, NJ). The switching apparatus, shown in Figs. 6 and 7, consists of the valve, located immediately adjacent to the phantom, and the actuating handle, located outside the bore of the magnet. A dummy phantom was added to the setup, as shown in Fig. 7, so that the pressure in both lines was equivalent. Slice-selective, spin-echo spectroscopy was used to monitor signal intensity versus time as the flowing media was cycled from water (60 s) to 0.2 mM Gd-BOPTA (60 s) and back to water (60 s). The acquisition parameters were: TR = 50 ms, TE = 10 ms, TH = 1.00 mm, and NT = 4. The flow rate was 55 mL/min.

Figure 6.

Four-way valve used in the switching apparatus. A: Polyoxymethylene (Delrin) valve-chamber casing. The eight threaded holes are for attaching the valve lid to the valve casing (top four) and for securing the valve to the switching apparatus (bottom four). B: Polyoxymethylene valve plug. C: Polyoxymethylene valve chamber lid. Note that one of the four small through-holes has no counterbore. The screw at this position, which can be seen in Fig. 7, is used as a guide for switch actuation. D: Assembly of the valve. Assembly was aided by applying a thin layer of high vacuum grease (Dow Corning Corporation; Midland, MI) between the valve chamber casing and the valve plug.

Figure 7.

Switching apparatus used to rapidly switch the lumenal media between water and contrast agent in the mock-DCE experiment (Fig. 8). A: The apparatus in position one, with water flowing to the phantom. B: The apparatus in position two, with 0.2 mM contrast agent flowing to the phantom. C: Photograph of the switching apparatus.

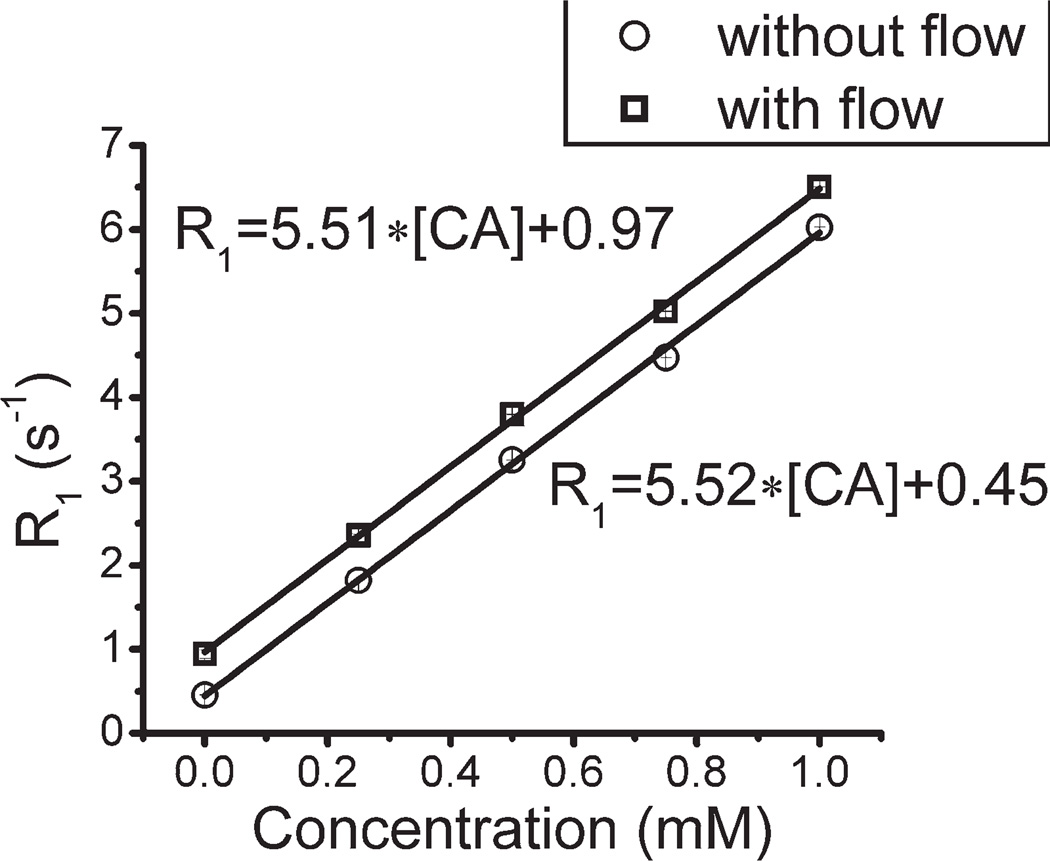

The longitudinal relaxivity of Gd-BOPTA (r1, mM−1 s−1) was determined for the multifiber phantom. Media Gd-BOPTA concentrations of 0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1 mM were allowed to completely equilibrate throughout all compartments of the phantom before relaxation measurements. At each equilibrated Gd-BOPTA concentration, the longitudinal relaxation rate constant (R1; s−1) was determined via inversion-recovery, spin-echo MR spectroscopy experiments without and with lumenal flow (10 mL/min). The experimental parameters were: TE = 10.0 ms, TH = 1.00 mm, NT = 4, number of steady-state scans = 5, and spectral width = 4006 Hz. For each experiment, the relaxation pre-delay (PD) was set to at least five times the inverse of R1, [5 × T1 (s)]. Table 1 lists these PD values and the inversion times (TI) used. Inversion-recovery time-course experiments were repeated three times at each Gd-BOPTA concentration, and the R1 values estimated with Bayesian analysis methods developed in our lab (software available for free download; see Bayesian Analysis of Common NMR Problems; http://bayesiananalysis.wustl.edu/index.html) (19).

Table 1.

Additional Experimental Parameters, Not Noted in the Text, Corresponding to Fig. 6

| Concentration of Gd-BOPTA (mM) | Predelay, PD (s) | First Inversion Time, TIfirsta (s) | Last Inversion Time (TIlast)a (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 11.50 | 0.23 | 11.50 |

| 0.25 | 3.00 | 0.05 | 3.00 |

| 0.50 | 1.75 | 0.03 | 1.75 |

| 0.75 | 1.25 | 0.02 | 1.25 |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 |

Thirty TI values were used spaced logarithmically from TIfirst to TIlast.

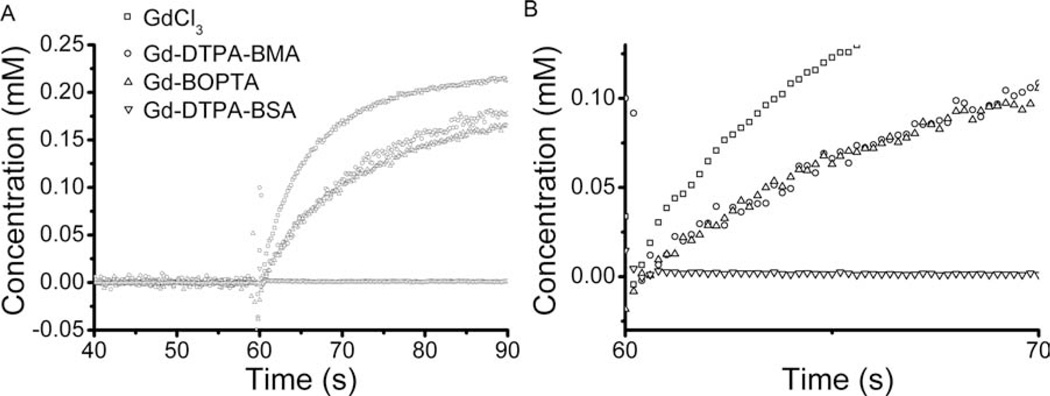

The mock-DCE experiment was repeated with the following additional contrast agents: 0.2 mM GdCl3 (gadolinium (III) chloride hexahydrate; P/N G7532; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.2 mM Gd-DTPA-BMA (gadodiamide; Omniscan; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and 0.02 mM Gd-DTPA-BSA (20). Signal intensities were converted to concentrations via the signal equation, measured relaxivities, and the T1 of bulk water in the presence of flow (21, 22). The uptake curves were quantitatively compared by calculating the initial slope from the first 20 data points immediately following contrast agent injection.

RESULTS

Figure 4 shows representative gradient-echo transaxial images from two single-fiber phantoms (A and B) and two multifiber phantoms (C and D). Because of differences in proton density, the fiber walls appear hypointense in these images. R1-mapping has established that, in the absence of lumenal flow, there is no significant difference in longitudinal rate constant in the fiber wall compared to homogeneous solution (23). Figure 5 shows representative spin-echo transaxial images from the same phantoms as in Fig. 4. Flow has suppressed signal in the lumenal compartment in these images via time-of-flight effects. The fibers in this figure appear hyperintense; the region of hyperintensity extends into the extrafiber space. This interesting effect is due to diffusion-driven longitudinal relaxation (vide infra) (23).

No fluid leakage was observed from any of the phantoms, and no diminution of signal was seen in compartments assumed to be nonflowing (i.e., the extralumen space). Following a period of several days of being continuously filled with water, the fiber within the single-fiber phantom, which had originally been taught, appeared flaccid. This change in physical appearance was accompanied by a decrease in proton-density contrast between the fiber wall and the extrafiber space (data not shown). As a consequence, we routinely use a new phantom for each set of experiments. Nonetheless, this effect did not impact any of our individual experiments, the longest of which lasted 15 h (23).

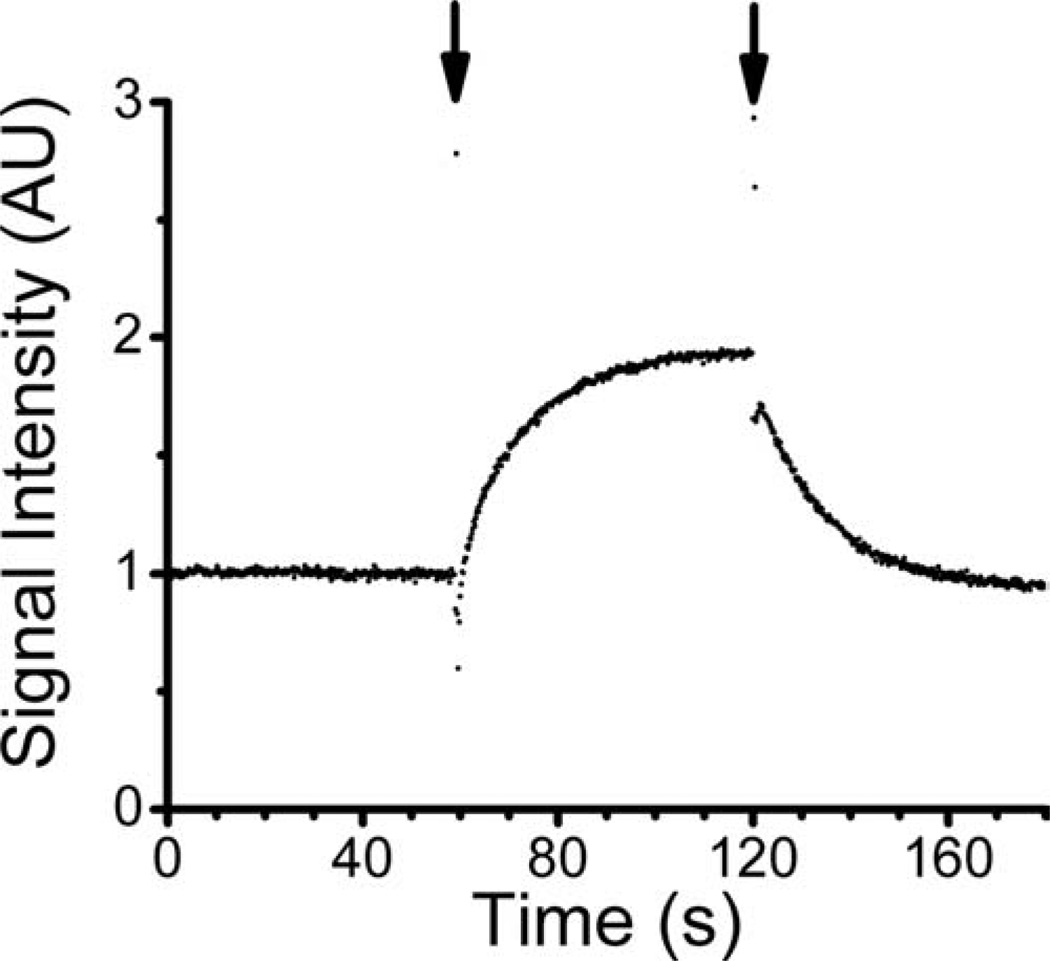

The results of a mock DCE-MRI experiment with Gd-BOPTA are shown in Fig. 8. Short-lived transients in the highly time-resolved (TR = 50 ms) signal profile accompany each “switching” of the flowing media (with/without contrast agent). These transients provide a convenient time stamp and can be seen in Fig. 8 at the 1- and 2-min marks of the signal profile.

Figure 8.

Mock-DCE experiment, as measured in the multifiber phantom. Signal intensity was monitored as a function of time, while lumenal media was cycled from water (duration ~60 s) to 0.2 mM Gd-BOPTA (duration ~60) and back to water (duration ~60 s). Short-lived transients, observed coincident with media switching, are highlighted with arrows.

The expected linear relationship between concentration of contrast agent and R1 of the equilibrated extrafiber space was verified, both in the absence and presence of lumenal flow (Fig. 9). However, while the slopes of this relationship, r1, are equivalent in the absence and presence of flow, the intercepts (R1,0 = R1 at 0 mM contrast agent) are different. This is because, in a slice-selective protocol, the flowing media brings fully polarized water 1H magnetization into the slice, which, during the TI period of the relaxation experiment, exchanges by diffusion with magnetization-perturbed water in the extrafiber space. (Recall, lumenal water is not observed directly due to time-of-flight effects.) As noted, this diffusion-driven relaxation effect, a phenomenon described in more detail elsewhere, can also be seen in Fig. 5 as an increase in signal amplitude within the fiber wall and in the extrafiber space near the fiber wall (23).

Figure 9.

Longitudinal relaxation rate (R1, s−1) measured in the multifiber phantom, as a function of Gd-BOPTA concentration, with (squares) and without (circles) lumenal flow. Linear regression fits, used to derive relaxivity values (r1, s−1 mM−1), are shown.

Concentration versus time curves from the mock-DCE experiment are shown in Fig. 10. Clearly, extravasation of contrast agent from the lumenal compartment to the extralumenal compartment is a function of the size of the contrast agent, with GdCl3 leaking the most rapidly and Gd-DTPA-BSA not diffusing through the fiber wall at all. The rate of contrast agent extravasation is compared quantitatively in Table 2 via the initial slope of the concentration uptake curve. These simple examples demonstrate the utility of the perfusion-sensitive MR phantom in revealing phenomena, perhaps unanticipated, that can impact various MR protocols and accompanying kinetic models.

Figure 10.

Mock-DCE experimental results for GdCl3 (squares), Gd-DTPA-BMA (circles), Gd-BOPTA (uppointing triangles), and Gd-DTPA-BSA (down-pointing triangles). The concentration of contrast agent in the extralumenal compartment (mM) was derived from dynamic signal intensity in the presence of lumenal flow (see Materials and Methods). B is an expanded view of A that highlights the initial contrast agent uptake, or, in the case of Gd-DTPA-BSA, the lack thereof. From top-to-bottom, traces in this figure are due to GdCl3, Gd-DTPA-BMA, Gd-BOPTA, and Gd-DTPA-BSA, respectively

Table 2.

Initial Slopes Calculated from the Various Contrast-Agent Uptake Curves Shown in Fig. 10

| Contrast Agent | GdCl3 | Gd-DTPA-BMA | Gd-BOPTA | Gd-DTPA-BSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 157 Daa | 574 Da | 668 Daa | ~68 kDa |

| Initial slope | 0.024 mM/s | 0.013 mM/s | 0.015 mM/s | 0.000 mM/s |

Molecular weight without counterion.

CONCLUSIONS

Design and construction details for two representative semipermeable hollow fiber phantoms, useful for testing and validation of perfusion-sensitive MR protocols and signal models, are described. The phantoms, single- and multifiber, are robust and allow control over the fractional volumes of the lumenal and extrafiber compartments. The phantoms’ small sizes allow high-spatial resolution to be achieved with small, high-sensitivity volume coils on preclinical MR imaging scanners, resolving individual compartments: fiber lumen, fiber wall, and extrafiber space. The small size also facilitates purging of air bubbles within the phantom, as the entire phantom can easily be submerged under vacuum. Complete suppression of lumenal signal can be achieved, if desired, with slice-selective, spin-echo protocols via time-of-flight. Mock-DCE experiments clearly demonstrate extravasation of low molecular-weight contrast agents from lumenal to extrafiber compartments. Although the expected linear relationship between concentration of contrast agent and longitudinal relaxation rate constant is demonstrated, the modification of this linear relationship by flow-enabled, diffusion- driven relaxation is revealed (23). These phantoms will contribute to efforts, ongoing in many laboratories, to develop, test, and validate, quantitative perfusion-sensitive MRI methods and associated signal models.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Y, Kim SE, DiBella EV, Parker DL. Flow measurement in MRI using arterial spin labeling with cumulative readout pulses—theory and validation. Med Phys. 2010;37:5801–5810. doi: 10.1118/1.3501881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osuga T, Obata T, Ikehira H. Detection of small degree of nonuniformity in dialysate flow in hollow-fiber dialyzer using proton magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osuga T, Obata T, Ikehira H. Proton magnetic resonance imaging of flow motion of heavy water injected into a hollow fiber dialyzer filled with saline. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy PA, Poh CK, Liao Z, Clark WR, Gao D. The use of magnetic resonance imaging to measure the local ultrafiltration rate in hemodialyzers. J Membr Sci. 2002;204:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laukemper-Ostendorf S, Lemke HD, Blümler P, Blümich B. NMR imaging of flow in hollow fiber hemodialyzers. J Membr Sci. 1998;138:287–295. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pangrle BJ, Walsh EG, Moore S, DiBiasio D. Investigation of fluid flow patterns in a hollow fiber module using magnetic resonance velocity imaging. Biotechnol Tech. 1989;3:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poh CK, Hardy PA, Liao Z, Clark WR, Gao D, Dibakar B, et al. Membrane Science and Technology Series. In: Dibakar Bhattacharyya, Butterfield D. Allan., editors. New Insights into Membrane Science and Technology: Polymeric and Biofunctional Membranes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 2003. pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Parker DL, Leypoldt JK. Flow distributions in hollow fiber hemodialyzers using magnetic resonance Fourier velocity imaging. ASAIO J. 1995;41:M678–M682. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199507000-00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heese F, Robson P, Hall LD. Quantification of fluid flow through a clinical blood filter and kidney dialyzer using magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Sens J. 2005;5:273–276. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poh CK, Hardy PA, Liao Z, Huang Z, Clark WR, Gao D. Effect of flow baffles on the dialysate flow distribution of hollow-fiber hemodialyzers: a nonintrusive experimental study using MRI. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:481–489. doi: 10.1115/1.1590355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poh CK, Hardy PA, Liao Z, Huang Z, Clark WR, Gao D. Effect of spacer yarns on the dialysate flow distribution of hemodialyzers: a magnetic resonance imaging study. ASAIO J. 2003;49:440–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donoghue C, Brideau M, Newcomer P, Pangrle B, DiBiasio D, Walsh E, et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to analyze the performance of hollow-fiber bioreactors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;665:285–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb42592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galons JP, Lope-Piedrafita S, Divijak JL, Corum C, Gillies RJ, Trouard TP. Uncovering of intracellular water in cultured cells. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:79–86. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thelwall PE, Neves AA, Brindle KM. Measurement of bioreactor perfusion using dynamic contrast agent-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;75:682–690. doi: 10.1002/bit.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilmann M, Vautier J, Robert P, Volk A. In vitro setup to study permeability characteristics of contrast agents by MRI. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2009;4:66–72. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Planchamp C, Gex-Fabry M, Dornier C, Quadri R, Reist M, Ivancevic MK, et al. Gd-BOPTA transport into rat hepatocytes: pharmacokinetic analysis of dynamic magnetic resonance images using a hollow-fiber bioreactor. Invest Radiol. 2004;39:506–515. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000129156.16054.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van As H, Lens P. Use of 1H NMR to study transport processes in porous biosystems. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;26:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebrahimi B, Swanson SD, Chupp TE. A microfabricated phantom for quantitative MR perfusion measurements: validation of singular value decomposition deconvolution method. IEEE Biomed Eng. 2010;57:2730–2736. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bretthorst GL, Hutton WC, Garbow JR, Ackerman JJH. Exponential parameter estimation (in NMR) using Bayesian probability theory. Concepts Magn Reson Part A. 2005;27:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dafni H, Landsman L, Schechter B, Kohen F, Neeman M. MRI and fluorescence microscopy of the acute vascular response to VEGF165: vasodilation, hyper-permeability and lymphatic uptake, followed by rapid inactivation of the growth factor. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:120–131. doi: 10.1002/nbm.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein MA, King KF, Zhou ZJ. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences. Amsterdam, Boston: Academic Press; 2004. p. 1017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson A, Buckley D, Parker GJM, editors. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Oncology. Berlin, New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JR, Ye Q, Neil JJ, Ackerman JJH, Garbow JR. Diffusion effects on longitudinal relaxation in poorly mixed compartments. J Magn Reson. 2011;211:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]